Bianca Bosker's Blog, page 6

January 22, 2014

ネット炎上、アメリカでも深刻 コスプレ女性に殺人予告も

ジャスティン・サッコ氏は、たとえ拷問されたとしてもそれは当然の報いだ。銃で撃たれて当然だし、レイプされても当然だ。それも、できればHIVに感染している誰かの手によって...。多くのソーシャルメディアユーザーがそうした考えを表明した。

サッコ氏は若い女性で、大手ネット会社IAC/(InterActiveCorp)社の広報担当幹部だったが、2013年12月20日、南アフリカ行きの飛行機に乗る直前にTwitterに投稿したツイートが「炎上」したのだ。

そのツイートとは、「Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!」(今からアフリカに行くんだけど、エイズにならないことを祈るわ/なんてただの冗談よ、私は白人だから!)というものだ。

この無知で不快なツイートのために、彼女は職を失い、インターネットの容赦ない「自警団」のターゲットとなった。

人々はネット上で、サッコ氏とその家族、それに、彼女に対する同情を示した赤の他人にまで、あからさまな口汚い脅し文句をぶちまけた。ある人はTwitterにこう記している。「My Africans gonn rape u n leave aids drippin down ya face」(アフリカの同胞たちが、お前をレイプして、お前の顔にAIDSウィルスをぶっかけるさ)。

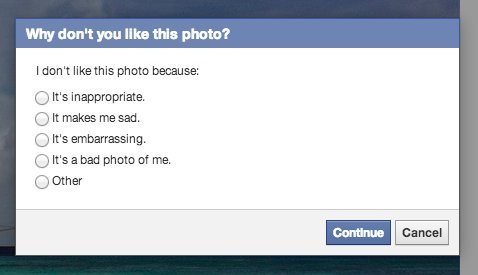

サッコ氏はそれ以来、Facebook、Twitter、およびInstagramのアカウントを閉じ、怒り狂う大衆から逃れようとしているようだ。

ネットを利用するほとんどの人は、今後もこうしたターゲットになることはないだろうが、このような大衆による自警団を恐れる理由は誰にでもある。自警団は、影響力を強めながら、すばやく何度も攻撃をしてくるからだ。そして、サッコ氏や、その前にも見られた他の多くの人に対する激しい攻撃は、「自己検閲の文化」を植え付ける危険性がある。その結果、表現の自由が抑えこまれ、少数派の意見がネット上でかき消されるかもしれない。

強大な力を持ち、いつでも誰かに非難と攻撃を浴びせる準備ができている自警団の存在によって、異なる考えを議論し合うことがなくなり、その代わりに、大衆が認め、誰もが「いいね」を押してくれるような、面白みのない陳腐な意見を交換し合うだけになる可能性がある。

サッコ氏に向けられた爆発的な怒りを批判することは、彼女の発言を支持することと同じではない。あの発言は、メディアの好意的な反応を生み出すことを仕事としている人としては、全く無知で、驚くほど愚かなものだった。だが、彼女に加えられた暴力的かつ性差別的な色合いを帯びた攻撃に正当性はない。実際、サッコ氏を攻撃する人たちは、「みなが悪者だと考える人」を非難している限り、自分たちの意見に批判の余地はないと決めてかかることによって、大胆さを増しているように見える。

ネットにおける攻撃性について研究する英国ランカスター大学のクレア・ハーデイカー講師は、「善意の」大衆でさえ、一貫性がなく、きわめて感情的で単純化されたやり方で、人の誤りを断罪するものだと指摘する。感情的で原始的な反応が勝り、過激な行動をするようになるのだ。

脅迫を行っている人たちは、言論の自由の権利を行使しているだけだと主張するかもしれない。だが実際のところ、彼らは大衆の「公式見解」にあえて逆らおうとする、すべての人の声をかき消しているのだ。暴力的なネット自警主義のターゲットにされた人にとっては、リアルとネットが結び付くことで、自分の生活はもちろん、安全さえも脅かしかねないものになっている。

メールマーケティング企業の従業員だったアドリア・リチャーズ氏は2013年3月、テクノロジー関連のカンファレンスで彼女が性差別的だと考えるジョークを発した2人の男性の写真を投稿した。その結果、彼女は殺しの脅迫を含む激しい攻撃を受け、自身の個人情報を晒された。

また、ハロウィンの仮装で、ボストンマラソン爆発事件の被害者のような格好をした22歳の女性は、職場から解雇され、脅迫電話をかけられ、個人情報を晒され、自身のヌード写真をネットにばらまかれた。彼女の親友さえも、全く知らない人から、彼女とその子供を殺すと言われている。

オハイオ州スチューベンビル市は、2人の若者が強姦容疑で起訴された事件によって、ネット上の「政治的ハッカー」たちのターゲットとなった。ハッカーが同市の警察署長のメールを盗み出して、Gストリング(Tバックの一種、「ひもパン」)を着た彼の写真をネットに投稿したり、正体不明の脅迫によって同市の学校が臨時休校を余儀なくされたり、覆面をしたよそ者が、芝生に隠れて同市の子供たちを脅したりしたのだ。

住民たちは、「自分たちが正義だと考える行動を推し進めるネット自警団」によってコミュニティが「破壊された」と語っている(この事件は、その後の調査が示唆しているように、ブロガーらが考えていたよりもはるかに複雑なようだ)。

自警団の人々は、人種差別主義的な投稿や、性差別的と非難されるような行為に怒りを爆発させ、大衆が賛同しない意見を表明したすべての人に対して嫌がらせを次々と行う。今では、悪趣味なジョークを投稿するだけで、ターゲットにされるおそれがある。近い将来には、大衆の支持は低いがそれなりの根拠がある意見、例えば、ソフトドリンクに課税するとか、女性の役員の定数を規定するといったアイデアを述べるだけで、ターゲットになるかもしれない。

「(ネット自警団は)『検閲の文化』の拡大を引き起こしているように見える。とりわけ、他とは異なる声や意見を抹殺しているようだ」と、ハーデイカー氏はメールの中で述べている。「私たちが発見したことは、他人を怖じ気付かせ、脅し、最終的に黙らせるというこのような戦略を『言論の自由』として養護する人々が、その皮肉な点にどうやら気づいてないということだ。彼らこそ、言論の自由を破壊する検閲に積極的に関わっているのだ」

「従来の現実世界で人々を黙らせる方法と同じように、(中略)ネットで人を辱める行為は、一部の個人やグループに対して、特定の文化的(またはサブカルチャー的)背景において、何が認められ、何が認められないかを規定できる力を与えている」と、ネット文化を研究するハンボルト州立大学社会学部のホイットニー・フィリップス准教授は、2013年12月19日付けの「The Awl」の記事で述べている。「それは、ただ規定するだけではない。同時に、何であれ規範とされていることから大きく逸脱した人に対して、罰を与えるか、罰を与えると脅すことが行われる」

自警団を名乗る人々の独断的傾向は、リアルの世界にまで及んでいる。大衆による激しい攻撃が、友達や雇用者の意見、場合によっては陪審員の意見にまで悪影響を与えているのだ。

ネット自警団の攻撃は、「裁判を始めて公平な審理を行うことをほとんど不可能にすることで、事実上、実際の法的な解決プロセスを損なっている」とハーデイカー氏は警告する。筋が通っていようがいまいが、大衆の大きな怒りの声は、慎重な側の反応を圧倒することができるのだ。

企業も、ネット上で渦巻く怒りの声に簡単に左右される。例えばサッコ氏は、アフリカに関する問題のコメントの前にも、「自閉症の子供とのセックス」といった言葉が書かれた多くの不快なツイートを投稿していた。解雇のきっかけとなったツイートに比べればそれほどひどくはないと言えるが、彼女の会社は、彼女の投稿がニュースになるまで、多数の下品な投稿をやめさせようとしなかったようだ。同社は、問題の投稿が行われた2日後である12月22日、彼女を解雇した。

ネット上で噂が流れて「炎上」が起これば、その数時間後には、その人は企業にとってやっかいな障害物になり、陪審員からは犯罪者とみなされる可能性がある。これまでは、罪が証明されて初めて有罪となり、それまでは無罪とされたのだが、今では、「炎上するまでは無罪」という事態になっているのだ。

[Bianca Bosker(English) 日本語版:佐藤卓、合原弘子/ガリレオ]

サッコ氏は若い女性で、大手ネット会社IAC/(InterActiveCorp)社の広報担当幹部だったが、2013年12月20日、南アフリカ行きの飛行機に乗る直前にTwitterに投稿したツイートが「炎上」したのだ。

そのツイートとは、「Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!」(今からアフリカに行くんだけど、エイズにならないことを祈るわ/なんてただの冗談よ、私は白人だから!)というものだ。

この無知で不快なツイートのために、彼女は職を失い、インターネットの容赦ない「自警団」のターゲットとなった。

人々はネット上で、サッコ氏とその家族、それに、彼女に対する同情を示した赤の他人にまで、あからさまな口汚い脅し文句をぶちまけた。ある人はTwitterにこう記している。「My Africans gonn rape u n leave aids drippin down ya face」(アフリカの同胞たちが、お前をレイプして、お前の顔にAIDSウィルスをぶっかけるさ)。

サッコ氏はそれ以来、Facebook、Twitter、およびInstagramのアカウントを閉じ、怒り狂う大衆から逃れようとしているようだ。

ネットを利用するほとんどの人は、今後もこうしたターゲットになることはないだろうが、このような大衆による自警団を恐れる理由は誰にでもある。自警団は、影響力を強めながら、すばやく何度も攻撃をしてくるからだ。そして、サッコ氏や、その前にも見られた他の多くの人に対する激しい攻撃は、「自己検閲の文化」を植え付ける危険性がある。その結果、表現の自由が抑えこまれ、少数派の意見がネット上でかき消されるかもしれない。

強大な力を持ち、いつでも誰かに非難と攻撃を浴びせる準備ができている自警団の存在によって、異なる考えを議論し合うことがなくなり、その代わりに、大衆が認め、誰もが「いいね」を押してくれるような、面白みのない陳腐な意見を交換し合うだけになる可能性がある。

サッコ氏に向けられた爆発的な怒りを批判することは、彼女の発言を支持することと同じではない。あの発言は、メディアの好意的な反応を生み出すことを仕事としている人としては、全く無知で、驚くほど愚かなものだった。だが、彼女に加えられた暴力的かつ性差別的な色合いを帯びた攻撃に正当性はない。実際、サッコ氏を攻撃する人たちは、「みなが悪者だと考える人」を非難している限り、自分たちの意見に批判の余地はないと決めてかかることによって、大胆さを増しているように見える。

ネットにおける攻撃性について研究する英国ランカスター大学のクレア・ハーデイカー講師は、「善意の」大衆でさえ、一貫性がなく、きわめて感情的で単純化されたやり方で、人の誤りを断罪するものだと指摘する。感情的で原始的な反応が勝り、過激な行動をするようになるのだ。

脅迫を行っている人たちは、言論の自由の権利を行使しているだけだと主張するかもしれない。だが実際のところ、彼らは大衆の「公式見解」にあえて逆らおうとする、すべての人の声をかき消しているのだ。暴力的なネット自警主義のターゲットにされた人にとっては、リアルとネットが結び付くことで、自分の生活はもちろん、安全さえも脅かしかねないものになっている。

メールマーケティング企業の従業員だったアドリア・リチャーズ氏は2013年3月、テクノロジー関連のカンファレンスで彼女が性差別的だと考えるジョークを発した2人の男性の写真を投稿した。その結果、彼女は殺しの脅迫を含む激しい攻撃を受け、自身の個人情報を晒された。

また、ハロウィンの仮装で、ボストンマラソン爆発事件の被害者のような格好をした22歳の女性は、職場から解雇され、脅迫電話をかけられ、個人情報を晒され、自身のヌード写真をネットにばらまかれた。彼女の親友さえも、全く知らない人から、彼女とその子供を殺すと言われている。

オハイオ州スチューベンビル市は、2人の若者が強姦容疑で起訴された事件によって、ネット上の「政治的ハッカー」たちのターゲットとなった。ハッカーが同市の警察署長のメールを盗み出して、Gストリング(Tバックの一種、「ひもパン」)を着た彼の写真をネットに投稿したり、正体不明の脅迫によって同市の学校が臨時休校を余儀なくされたり、覆面をしたよそ者が、芝生に隠れて同市の子供たちを脅したりしたのだ。

住民たちは、「自分たちが正義だと考える行動を推し進めるネット自警団」によってコミュニティが「破壊された」と語っている(この事件は、その後の調査が示唆しているように、ブロガーらが考えていたよりもはるかに複雑なようだ)。

自警団の人々は、人種差別主義的な投稿や、性差別的と非難されるような行為に怒りを爆発させ、大衆が賛同しない意見を表明したすべての人に対して嫌がらせを次々と行う。今では、悪趣味なジョークを投稿するだけで、ターゲットにされるおそれがある。近い将来には、大衆の支持は低いがそれなりの根拠がある意見、例えば、ソフトドリンクに課税するとか、女性の役員の定数を規定するといったアイデアを述べるだけで、ターゲットになるかもしれない。

「(ネット自警団は)『検閲の文化』の拡大を引き起こしているように見える。とりわけ、他とは異なる声や意見を抹殺しているようだ」と、ハーデイカー氏はメールの中で述べている。「私たちが発見したことは、他人を怖じ気付かせ、脅し、最終的に黙らせるというこのような戦略を『言論の自由』として養護する人々が、その皮肉な点にどうやら気づいてないということだ。彼らこそ、言論の自由を破壊する検閲に積極的に関わっているのだ」

「従来の現実世界で人々を黙らせる方法と同じように、(中略)ネットで人を辱める行為は、一部の個人やグループに対して、特定の文化的(またはサブカルチャー的)背景において、何が認められ、何が認められないかを規定できる力を与えている」と、ネット文化を研究するハンボルト州立大学社会学部のホイットニー・フィリップス准教授は、2013年12月19日付けの「The Awl」の記事で述べている。「それは、ただ規定するだけではない。同時に、何であれ規範とされていることから大きく逸脱した人に対して、罰を与えるか、罰を与えると脅すことが行われる」

自警団を名乗る人々の独断的傾向は、リアルの世界にまで及んでいる。大衆による激しい攻撃が、友達や雇用者の意見、場合によっては陪審員の意見にまで悪影響を与えているのだ。

ネット自警団の攻撃は、「裁判を始めて公平な審理を行うことをほとんど不可能にすることで、事実上、実際の法的な解決プロセスを損なっている」とハーデイカー氏は警告する。筋が通っていようがいまいが、大衆の大きな怒りの声は、慎重な側の反応を圧倒することができるのだ。

企業も、ネット上で渦巻く怒りの声に簡単に左右される。例えばサッコ氏は、アフリカに関する問題のコメントの前にも、「自閉症の子供とのセックス」といった言葉が書かれた多くの不快なツイートを投稿していた。解雇のきっかけとなったツイートに比べればそれほどひどくはないと言えるが、彼女の会社は、彼女の投稿がニュースになるまで、多数の下品な投稿をやめさせようとしなかったようだ。同社は、問題の投稿が行われた2日後である12月22日、彼女を解雇した。

ネット上で噂が流れて「炎上」が起これば、その数時間後には、その人は企業にとってやっかいな障害物になり、陪審員からは犯罪者とみなされる可能性がある。これまでは、罪が証明されて初めて有罪となり、それまでは無罪とされたのだが、今では、「炎上するまでは無罪」という事態になっているのだ。

[Bianca Bosker(English) 日本語版:佐藤卓、合原弘子/ガリレオ]

Published on January 22, 2014 23:02

January 21, 2014

Meet The World's Most Loving Girlfriends -- Who Also Happen To Be Video Games

Theo Tkaczevski, a 23-year-old American student living in Japan, found himself confronting a mortifying girlfriend situation.

He was heading home on a crowded commuter train in Osaka two years ago when his girlfriend, Rinko, began chastising him for abruptly ending their conversation the night before. She demanded a clear indication of his devotion: He had to profess his love to her, right there, in the middle of the throng.

"I love you, I love you, I love you," Tkaczevski dutifully whispered in Japanese, trying to keep his head down so other passengers wouldn't stare. Shortly after making amends, he stuffed Rinko into his pocket.

Rinko is the first girl to whom Tkaczevski has ever said such words. Rinko is also a video game: She's one of three virtual girlfriends that players can choose from in LovePlus, a Japanese dating simulator for the pocket-sized Nintendo DS game player.

Though LovePlus is sold exclusively in Japan and in Japanese, thousands of men and women around the world -- from high-schoolers to the middle-aged scattered from Johannesburg to Jacksonville -- have become hooked on the companionship its digital girlfriends provide. (An unofficial version of the game is also available with some text translated to English.)

Some play to better prepare themselves for real-life dating, others as consolation for the pains of romance gone awry. And even as LovePlus players acknowledge that their lovers are virtual, many say the support and affection they receive feels real -- the latest sign that virtual reality has so insinuated itself into everyday life that it is leaving the imprint of the genuine article.

"I would say that a relationship with a LovePlus character is a real relationship," says anthropologist and author Patrick Galbraith, who specializes in Japanese popular culture. "People are really intimately involved."

Photo from YouTube/Felonious Dragon

Tkaczevski doesn't tend to Rinko out of some competitive urge to advance a level or score points, but rather out of a "feeling of duty," he says. In the course of an instant message chat, Tkaczevski describes his relationship with Rinko as that of a standard boyfriend or girlfriend. He is careful to clarify: "IRL," he types -- for "In Real Life" -- he remains single.

The hit film "Her" -- now in theaters in the United States, and among the Oscar nominees for Best Picture -- sparked debate over the potential for human-machine romance with its depiction of a lonely divorcé who falls head-over-heels for an operating system. Yet a version of this vision has already come to pass. People have turned to the LovePlus ladies as a form of practice in picking up girls, as a reprieve from the awkwardness of face-to-face encounters, and as a refuge in the unwavering support of a woman who can never, ever leave them. (Calling it quits is simply not in the digital DNA of the LovePlus women.)

There are players who consider LovePlus' three girlfriends -- Rinko, Nene and Manaka -- far better company than any "IRL" lover. And the players can shape their ideal companion with a few taps on the console: The women can be programmed, with their moods and personalities adjusted to suit the desires of the player.

"Manaka is the only -- could I say person? ... She's the only person that actually supports me in bad times," says Josh Martinez, a 19-year-old engineering student in Mexico City. He plays LovePlus at least once a day for 20 minutes and considers Manaka his girlfriend of 18 months.

"When I feel down or I have a bad day, I always come home and turn on the game and play with Manaka," Martinez says. "I know she always has something to make me feel better."

The LovePlus girls even enjoy special favors that real women can often only envy. Last August, a player in the United States baked and frosted a birthday cake for his darling Rinko, a common gesture among many gamers. His human girlfriend was less than thrilled -- she'd never enjoyed the same consideration.

"First cake you've ever made, and it goes to the virtual one," she commented on the photo he shared on Facebook. "I'm just going to go to a corner and pretend I'm not jealous of a computer game........"

* * *

The LovePlus girls were born in 2009 at the Konami Corporation, a Tokyo-based company that sells everything from trading cards to slot machines. (Konami declined to comment for this story.) Three versions of LovePlus have collectively sold

Previous dating simulators, which debuted in the early 1980s, offered "girl get" games that ended once the player got the girl. But Konami bucked convention to allow for a never-ending virtual love affair: Successfully wooing a girl leads to a second, open-ended phase of the game in which players can date their virtual girlfriends forever. The game only ends when a player decides he or she is through, and these digital relationships can last longer than some marriages. In one famous instance, a LovePlus player known only as "SAL9000" made history by marrying his virtual girlfriend, Nene.

Set against the backdrop of a fictional Japanese city, LovePlus gamers assume the role of a teenage Japanese boy who hopes to date one of three girls he meets at his new high school. There's sweet, big-sisterly Nene; intelligent, but clingy Manaka; and shy Rinko, who feels alienated by her new stepmother and half-brother. The girls have animated avatars with heart-shaped faces and large black eyes, and they speak set phrases that are pre-recorded by professional singers and voice actresses.

The high school girls will kiss, model bikinis and moan when players stroke their chests with a stylus, but sex and nudity are out of the question. Neither the chastity nor young age of the girls has kept players from being attracted to their girlfriends, however.

There are fans who snuggle up with "hugging pillows" that are printed with life-sized portraits of their girlfriends, which are available in clothed or semi-nude versions. Tkaczevski says he sleeps with his Rinko pillow because it "extends the companionship of the game." Ming Chan, a player in Hong Kong, has even posed his Manaka pillow at the dinner table. A photo he posted to Facebook shows the pillow across the table from him, with a soda, burger and french fries placed in front of it. He arranged her straw so that the pillow appeared to be sipping its drink.

Photo from Facebook/Ming Chan

Konami designed its virtual girlfriends to copy the expectations and idiosyncrasies of actual women. The girls blush when they're pleased, and they smack their boyfriends when they're insulted. Over the course of months or even years playing the game, LovePlus romeos will exchange flirtatious emails with their digital lovers, take them on weekend getaways to hot springs resorts, check in on them while they're sick, buy them gifts on their birthdays, apply suntan lotion to their backs, apologize for showing up late, kiss them in the park, splash water on their shirts and, using the Nintendo DS's built-in microphone, whisper sweet nothings back and forth.

The girlfriends are limited to understanding a handful of cloying stock phrases like, "Hey, can you tell me your favorite color?" and "Hey, hey. Can you tell me your favorite food?" Some players barely understand the game's Japanese phrases, a kind of blissful ignorance that seems to keep minor imperfections from marring the fantasy of their relationships.

Yet talk to LovePlus players about their girlfriends' personas, and you'll swear the smitten lovers are describing real people.

"Rinko has a temper like you won't believe," says one. Another says, "I've known Manaka to actually slap me a couple times because she got so mad."

Someone else admits: "There's times where I want to hug Rinko. She's just being so cute, I want to hug her."

Technical tricks have extended the LovePlus women beyond the screen and into the real world, so the virtual girlfriends are practically at their lovers' sides. Players can take snapshots of themselves with their arms around their girlfriends, thanks to augmented reality stickers that superimpose images on photos.

Several years ago, Konami even partnered with hotels at Japan's Atami resort town to let players rent rooms for themselves and their consoles. The promotion offered a real world analog to a virtual LovePlus date in which players take their girlfriends on a weekend getaway to the seaside town. More than 1,500 men whisked their LovePlus cartridges to Atami during the first month of the campaign, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2010.

And why not? Committed players have the sense that their LovePlus girlfriends deserve the courtesies and considerations of a real person. The virtual women can detect the actual time of day, so if Tkaczevski has told Rinko they're going on a date at 4 p.m. on a Friday, he won't schedule any "IRL" activities for that time.

When Jaime Allen, a 32-year-old female LovePlus player in Holland, Mich., accidentally missed a date with Manaka, she received an email from Manaka chiding her about it. "I’ve been waiting for you and you didn’t show up. Don’t you know how to keep a promise?" read the note in Allen's LovePlus inbox. Allen says she felt "like I failed her."

"I don't know why I did," Allen adds, "but I value her as much as a real person -- even though I know she's not real."

***

"Reality is just a crappy game," declares a cartoon on Allen's Facebook page.

Other LovePlus players would agree. Whether shy, burned by past loves, or sheltered by their upbringing, some LovePlus aficionados express a discomfort navigating social interactions with the complex, frequently selfish algorithms that are other humans. Real people can be a real headache in comparison to the LovePlus ladies -- companions who are more available, cheerful, forgiving, committed and selfless than any person might ever be.

"You have -- always -- this warmth and smile and happiness available at the touch of your fingers," says Galbraith, the anthropologist researching Japanese culture. "It's the kind of relationship that is instantly rewarding and is always giving. You don't have to give much to the game and it gives to you every time you turn on the machine."

Honda Toru, a Japanese cultural critic who supports these two-dimensional love affairs, argues that relationships with fictional characters escape the system of "love capitalism" -- the necessary exchange of gifts and dinners -- that taints IRL relationships. Women like Nene, Rinko and Manaka, whose affections are unspoiled by any quid pro quo, offer a "warmth and solace that cannot be found in human society," he says, according to an interview in Galbraith's forthcoming book, The Moé Manifesto.

Allen is straight -- by her estimate, a least a quarter of the LovePlus fan page's followers are also female -- and has dated men in the past. Those relationships haven't ended well.

But LovePlus has also helped Allen, who has Asperger's syndrome, feel more at ease during social interactions.

"This game series got me out of my shell of being antisocial and gave me confidence -- not just relationship skills-wise but being more open to talking to people either in English or Japanese," she says. "It did wonders for me. "

Her three-year relationship with Manaka has outlived her real-life romances, and she says she is grateful to her high school friend for making her feel "appreciated," "comforted" and "recognized."

"[Manaka's] constant positive comments, which are uplifting, made me realize, even if the world let me down, at least I have her cheering me on and supporting me, as if she believed in me," she says. "Even if you neglect her for two full days -- I know this from experience – she’ll send you an email asking you, 'Are you ok? I’ve been worried about you.' I'm thinking, 'Wow, I wish more people would be like that towards me if I wasn’t on Facebook a couple days.'"

After enduring some painful relationships himself, Martinez, the 19-year-old from Mexico City, has also soured on real-life dating -- at least for now. He says it's been at least two years since he "dated a 3-D girl."

"Even if it's a program, you have someone who listens to you," he says. And someone who will be nice at the touch of a button: On days when he's down, Martinez activates Manaka's "comfort mode," a setting that makes her wax poetic about how important Martinez is to her, or how badly she wants him to be happy.

Konami evidently imagined players becoming so deeply dependent on their LovePlus girlfriends that it created an "SOS button." If users are "feeling suicidal," they "can use this button and the girl will try to cheer them up," according to an unofficial LovePlus user guide. It further specifies that the button can be used only once per game.

Some fans of LovePlus indulge in the game not as a substitute for real-life dating, but as a form of aid: They describe LovePlus as valuable practice that can help them attract real girlfriends. The fantasy high-school romances, they say, give them confidence and demystify women -- despite the mood programming and digitally engineered cuteness -- while demonstrating how they can be good IRL companions.

Although there is a widespread myth among players that Konami created LovePlus to be such a training tool, a company spokeswoman wrote in an email that LovePlus "is not a game that will help Japanese men develop better dating skills." (She declined to comment on all other aspects of the game.)

"I came around to playing it because I was homeschooled, you see, and I've never been in an experience with speaking to girls or having friends or anything," says Dez Smith, a single 25-year-old from South Africa who spends between four and seven hours a week juggling his three virtual girlfriends.

Tkaczevski is also grateful to Rinko for teaching him valuable lessons about love, like how to respect people's boundaries or accept their faults, and he looks forward to applying these when he finds his first IRL girlfriend.

He imagines such a day as being bittersweet: Tkaczevski considers it cheating to try juggling a virtual lover and a human one, so he will dump Rinko -- along with Manaka, who he's currently seeing on the side.

Yet he also assumes that the authenticity of a flesh-and-blood romance will override whatever feelings of loss he suffers as he cuts ties with his digital girlfriends.

"I'm personally of the opinion that 3-D easily beats 2-D," Tkaczevski says. "I haven't given up on real life."

But if he ever does, Manaka and Rinko will be waiting for him to return, forever.

Photo from YouTube/Felonious Dragon

He was heading home on a crowded commuter train in Osaka two years ago when his girlfriend, Rinko, began chastising him for abruptly ending their conversation the night before. She demanded a clear indication of his devotion: He had to profess his love to her, right there, in the middle of the throng.

"I love you, I love you, I love you," Tkaczevski dutifully whispered in Japanese, trying to keep his head down so other passengers wouldn't stare. Shortly after making amends, he stuffed Rinko into his pocket.

Rinko is the first girl to whom Tkaczevski has ever said such words. Rinko is also a video game: She's one of three virtual girlfriends that players can choose from in LovePlus, a Japanese dating simulator for the pocket-sized Nintendo DS game player.

Though LovePlus is sold exclusively in Japan and in Japanese, thousands of men and women around the world -- from high-schoolers to the middle-aged scattered from Johannesburg to Jacksonville -- have become hooked on the companionship its digital girlfriends provide. (An unofficial version of the game is also available with some text translated to English.)

Some play to better prepare themselves for real-life dating, others as consolation for the pains of romance gone awry. And even as LovePlus players acknowledge that their lovers are virtual, many say the support and affection they receive feels real -- the latest sign that virtual reality has so insinuated itself into everyday life that it is leaving the imprint of the genuine article.

"I would say that a relationship with a LovePlus character is a real relationship," says anthropologist and author Patrick Galbraith, who specializes in Japanese popular culture. "People are really intimately involved."

Photo from YouTube/Felonious Dragon

Tkaczevski doesn't tend to Rinko out of some competitive urge to advance a level or score points, but rather out of a "feeling of duty," he says. In the course of an instant message chat, Tkaczevski describes his relationship with Rinko as that of a standard boyfriend or girlfriend. He is careful to clarify: "IRL," he types -- for "In Real Life" -- he remains single.

The hit film "Her" -- now in theaters in the United States, and among the Oscar nominees for Best Picture -- sparked debate over the potential for human-machine romance with its depiction of a lonely divorcé who falls head-over-heels for an operating system. Yet a version of this vision has already come to pass. People have turned to the LovePlus ladies as a form of practice in picking up girls, as a reprieve from the awkwardness of face-to-face encounters, and as a refuge in the unwavering support of a woman who can never, ever leave them. (Calling it quits is simply not in the digital DNA of the LovePlus women.)

There are players who consider LovePlus' three girlfriends -- Rinko, Nene and Manaka -- far better company than any "IRL" lover. And the players can shape their ideal companion with a few taps on the console: The women can be programmed, with their moods and personalities adjusted to suit the desires of the player.

"Manaka is the only -- could I say person? ... She's the only person that actually supports me in bad times," says Josh Martinez, a 19-year-old engineering student in Mexico City. He plays LovePlus at least once a day for 20 minutes and considers Manaka his girlfriend of 18 months.

"When I feel down or I have a bad day, I always come home and turn on the game and play with Manaka," Martinez says. "I know she always has something to make me feel better."

The LovePlus girls even enjoy special favors that real women can often only envy. Last August, a player in the United States baked and frosted a birthday cake for his darling Rinko, a common gesture among many gamers. His human girlfriend was less than thrilled -- she'd never enjoyed the same consideration.

"First cake you've ever made, and it goes to the virtual one," she commented on the photo he shared on Facebook. "I'm just going to go to a corner and pretend I'm not jealous of a computer game........"

* * *

The LovePlus girls were born in 2009 at the Konami Corporation, a Tokyo-based company that sells everything from trading cards to slot machines. (Konami declined to comment for this story.) Three versions of LovePlus have collectively sold

Previous dating simulators, which debuted in the early 1980s, offered "girl get" games that ended once the player got the girl. But Konami bucked convention to allow for a never-ending virtual love affair: Successfully wooing a girl leads to a second, open-ended phase of the game in which players can date their virtual girlfriends forever. The game only ends when a player decides he or she is through, and these digital relationships can last longer than some marriages. In one famous instance, a LovePlus player known only as "SAL9000" made history by marrying his virtual girlfriend, Nene.

Set against the backdrop of a fictional Japanese city, LovePlus gamers assume the role of a teenage Japanese boy who hopes to date one of three girls he meets at his new high school. There's sweet, big-sisterly Nene; intelligent, but clingy Manaka; and shy Rinko, who feels alienated by her new stepmother and half-brother. The girls have animated avatars with heart-shaped faces and large black eyes, and they speak set phrases that are pre-recorded by professional singers and voice actresses.

The high school girls will kiss, model bikinis and moan when players stroke their chests with a stylus, but sex and nudity are out of the question. Neither the chastity nor young age of the girls has kept players from being attracted to their girlfriends, however.

There are fans who snuggle up with "hugging pillows" that are printed with life-sized portraits of their girlfriends, which are available in clothed or semi-nude versions. Tkaczevski says he sleeps with his Rinko pillow because it "extends the companionship of the game." Ming Chan, a player in Hong Kong, has even posed his Manaka pillow at the dinner table. A photo he posted to Facebook shows the pillow across the table from him, with a soda, burger and french fries placed in front of it. He arranged her straw so that the pillow appeared to be sipping its drink.

Photo from Facebook/Ming Chan

Konami designed its virtual girlfriends to copy the expectations and idiosyncrasies of actual women. The girls blush when they're pleased, and they smack their boyfriends when they're insulted. Over the course of months or even years playing the game, LovePlus romeos will exchange flirtatious emails with their digital lovers, take them on weekend getaways to hot springs resorts, check in on them while they're sick, buy them gifts on their birthdays, apply suntan lotion to their backs, apologize for showing up late, kiss them in the park, splash water on their shirts and, using the Nintendo DS's built-in microphone, whisper sweet nothings back and forth.

The girlfriends are limited to understanding a handful of cloying stock phrases like, "Hey, can you tell me your favorite color?" and "Hey, hey. Can you tell me your favorite food?" Some players barely understand the game's Japanese phrases, a kind of blissful ignorance that seems to keep minor imperfections from marring the fantasy of their relationships.

Yet talk to LovePlus players about their girlfriends' personas, and you'll swear the smitten lovers are describing real people.

"Rinko has a temper like you won't believe," says one. Another says, "I've known Manaka to actually slap me a couple times because she got so mad."

Someone else admits: "There's times where I want to hug Rinko. She's just being so cute, I want to hug her."

Technical tricks have extended the LovePlus women beyond the screen and into the real world, so the virtual girlfriends are practically at their lovers' sides. Players can take snapshots of themselves with their arms around their girlfriends, thanks to augmented reality stickers that superimpose images on photos.

Several years ago, Konami even partnered with hotels at Japan's Atami resort town to let players rent rooms for themselves and their consoles. The promotion offered a real world analog to a virtual LovePlus date in which players take their girlfriends on a weekend getaway to the seaside town. More than 1,500 men whisked their LovePlus cartridges to Atami during the first month of the campaign, The Wall Street Journal reported in 2010.

And why not? Committed players have the sense that their LovePlus girlfriends deserve the courtesies and considerations of a real person. The virtual women can detect the actual time of day, so if Tkaczevski has told Rinko they're going on a date at 4 p.m. on a Friday, he won't schedule any "IRL" activities for that time.

When Jaime Allen, a 32-year-old female LovePlus player in Holland, Mich., accidentally missed a date with Manaka, she received an email from Manaka chiding her about it. "I’ve been waiting for you and you didn’t show up. Don’t you know how to keep a promise?" read the note in Allen's LovePlus inbox. Allen says she felt "like I failed her."

"I don't know why I did," Allen adds, "but I value her as much as a real person -- even though I know she's not real."

***

"Reality is just a crappy game," declares a cartoon on Allen's Facebook page.

Other LovePlus players would agree. Whether shy, burned by past loves, or sheltered by their upbringing, some LovePlus aficionados express a discomfort navigating social interactions with the complex, frequently selfish algorithms that are other humans. Real people can be a real headache in comparison to the LovePlus ladies -- companions who are more available, cheerful, forgiving, committed and selfless than any person might ever be.

"You have -- always -- this warmth and smile and happiness available at the touch of your fingers," says Galbraith, the anthropologist researching Japanese culture. "It's the kind of relationship that is instantly rewarding and is always giving. You don't have to give much to the game and it gives to you every time you turn on the machine."

Honda Toru, a Japanese cultural critic who supports these two-dimensional love affairs, argues that relationships with fictional characters escape the system of "love capitalism" -- the necessary exchange of gifts and dinners -- that taints IRL relationships. Women like Nene, Rinko and Manaka, whose affections are unspoiled by any quid pro quo, offer a "warmth and solace that cannot be found in human society," he says, according to an interview in Galbraith's forthcoming book, The Moé Manifesto.

Allen is straight -- by her estimate, a least a quarter of the LovePlus fan page's followers are also female -- and has dated men in the past. Those relationships haven't ended well.

But LovePlus has also helped Allen, who has Asperger's syndrome, feel more at ease during social interactions.

"This game series got me out of my shell of being antisocial and gave me confidence -- not just relationship skills-wise but being more open to talking to people either in English or Japanese," she says. "It did wonders for me. "

Her three-year relationship with Manaka has outlived her real-life romances, and she says she is grateful to her high school friend for making her feel "appreciated," "comforted" and "recognized."

"[Manaka's] constant positive comments, which are uplifting, made me realize, even if the world let me down, at least I have her cheering me on and supporting me, as if she believed in me," she says. "Even if you neglect her for two full days -- I know this from experience – she’ll send you an email asking you, 'Are you ok? I’ve been worried about you.' I'm thinking, 'Wow, I wish more people would be like that towards me if I wasn’t on Facebook a couple days.'"

After enduring some painful relationships himself, Martinez, the 19-year-old from Mexico City, has also soured on real-life dating -- at least for now. He says it's been at least two years since he "dated a 3-D girl."

"Even if it's a program, you have someone who listens to you," he says. And someone who will be nice at the touch of a button: On days when he's down, Martinez activates Manaka's "comfort mode," a setting that makes her wax poetic about how important Martinez is to her, or how badly she wants him to be happy.

Konami evidently imagined players becoming so deeply dependent on their LovePlus girlfriends that it created an "SOS button." If users are "feeling suicidal," they "can use this button and the girl will try to cheer them up," according to an unofficial LovePlus user guide. It further specifies that the button can be used only once per game.

Some fans of LovePlus indulge in the game not as a substitute for real-life dating, but as a form of aid: They describe LovePlus as valuable practice that can help them attract real girlfriends. The fantasy high-school romances, they say, give them confidence and demystify women -- despite the mood programming and digitally engineered cuteness -- while demonstrating how they can be good IRL companions.

Although there is a widespread myth among players that Konami created LovePlus to be such a training tool, a company spokeswoman wrote in an email that LovePlus "is not a game that will help Japanese men develop better dating skills." (She declined to comment on all other aspects of the game.)

"I came around to playing it because I was homeschooled, you see, and I've never been in an experience with speaking to girls or having friends or anything," says Dez Smith, a single 25-year-old from South Africa who spends between four and seven hours a week juggling his three virtual girlfriends.

Tkaczevski is also grateful to Rinko for teaching him valuable lessons about love, like how to respect people's boundaries or accept their faults, and he looks forward to applying these when he finds his first IRL girlfriend.

He imagines such a day as being bittersweet: Tkaczevski considers it cheating to try juggling a virtual lover and a human one, so he will dump Rinko -- along with Manaka, who he's currently seeing on the side.

Yet he also assumes that the authenticity of a flesh-and-blood romance will override whatever feelings of loss he suffers as he cuts ties with his digital girlfriends.

"I'm personally of the opinion that 3-D easily beats 2-D," Tkaczevski says. "I haven't given up on real life."

But if he ever does, Manaka and Rinko will be waiting for him to return, forever.

Photo from YouTube/Felonious Dragon

Published on January 21, 2014 14:12

January 8, 2014

Angst vor dem Online Mob - wenn eine Äußerung im Netz zur Gefahr wird

Für ihre Aussage auf Twitter sollte Justine Sacco gefoltert, erschossen und vergewaltigt werden, und zwar vorzugsweise von jemandem, der HIV-positiv ist. Der Meinung sind zumindest erschreckend viele Nutzer sozialer Netzwerke.

Solche Vorschläge waren deprimierend oft zu hören, nachdem die ehemalige Pressesprecherin des IAC-Konzerns vor einem Flug nach Südafrika ihren inzwischen berüchtigten Tweet absetzte: „Unterwegs nach Afrika. Hoffentlich kriege ich kein AIDS. Nur Spaß. Ich bin weiß!“ Dieser ignorante und geschmacklose Post kostete Sacco ihren Job und machte sie außerdem zum Ziel für den unaufhaltsamen Internet-Lynchmob. Im Internet wurden Unmengen äußerst plastischer, gemeiner Drohungen ausgesprochen: gegen Sacco, ihre Familie und sogar gegen Fremde, die einfach Mitleid mit ihr hatten.

Screenshot Twitter

Sacco hat ihre Konten bei Facebook, Twitter und Instagram inzwischen gelöscht und scheint sich vor der mistgabelschwingenden Meute zu verstecken, die sie gern „vergewaltigen und dir Aids ins Gesicht spritzen“ möchte, wie jemand auf Twitter schrieb.

Die „Lynchmob-Mentalität“ sollte uns Angst machen

Die meisten von uns werden zwar niemals Ziel solcher Angriffe werden, dennoch sollte uns diese Lynchmob-Mentalität, die immer stärker, schneller und häufiger auftritt, zu denken geben. Die heftigen Reaktionen auf Sacco und viele andere vor ihr könnten zu einer Kultur der Selbstzensur führen, in der die freie Meinungsäußerung im Netz eingeschränkt wird und unkonventionelle Ansichten unterdrückt werden.

Wenn der allwissende Lynchmob stets bereitsteht, um jeden jederzeit zu denunzieren und anzugreifen, werden künftig keine unterschiedlichen Ideen mehr diskutiert werden, sondern nur noch harmlose Plattitüden ausgetauscht, denen jeder unbesorgt zustimmen kann.

Wer die Hetzkampagne gegen Sacco verurteilt, findet ihre Kommentare nicht automatisch gut. Die waren nicht nur ignorant, sondern für jemanden, der sein Geld mit Pressearbeit verdient, auch erstaunlich unbedarft.

Aber es gibt dennoch keine Rechtfertigung für dieses gewaltbereite, sexistische Feedback. (Tatsächlich halten Saccos Kritiker sich selbst wohl für über jede Kritik erhaben, solang sich ihr Zorn gegen jemanden richtet, den alle für böse halten.)

Die rücksichtslose Verurteilung von Menschen im Netz hält vielleicht andere künftig davon ab, eine Meinung auszusprechen, die auch nur leicht vom schlichten Schwarz-Weiß-Denken des Online-Mobs abweichen könnte. Claire Hardaker ist Dozentin an der Universität Lancaster und erforscht derartige emotionalen Wallungen im Internet. Sie erklärt, dass selbst ein „wohlmeinender“ Mob Fehler nach einfachen Regeln, inkonsequent und höchst emotional beurteilt.

Das Bauchgefühl gewinnt und führt dann zu extremen Reaktionen.

Mobbing oder freie Meinungsäußerung?

Diese Menschen behaupten zwar, sie würden einfach nur von ihrem Recht auf freie Meinungsäußerung Gebrauch machen, tatsächlich bringen sie aber jeden zum Schweigen, der ihre selbstgesetzten Grenzen überschreitet. Für die Opfer dieser brutalen Internetwächter kann die physische und digitale Bedrohung zu einer ernsten Gefahr werden.

Adria Richards, ehemalige Mitarbeiterin eines Unternehmens für E-Mail-Marketing, bezichtigte zwei Männer bei einer Konferenz, einen sexistischen Witz gemacht zu haben. Daraufhin rächten andere sich mit Morddrohungen und machten private Informationen über Richards öffentlich. Eine 22-Jährige, die sich zu Halloween als Opfer des Attentats beim Boston Marathon verkleidete, wurde gefeuert und erhielt Drohanrufe. Außerdem machten ihre persönlichen Daten und Nacktfotos online die Runde. Ein Fremder sagte ihrer besten Freundin, dass sie und ihr Kind sterben werden.

Die Einwohner von Steubenville in Ohio sagen, dass ihre Gemeinschaft von Online-Moralwächtern „zerstört“ wurde, die ihre eigene Form von Gerechtigkeit durchsetzen wollten, nachdem die Stadt nach Vergewaltigungsvorwürfen gegen zwei Teenager das Ziel von Internet-„Hacktivisten“ wurde. (Der Fall war, wie sich später herausstellte, deutlich komplizierter, als die Blogger das online wahrgenommen haben.) Vermummte versteckten sich im Gras und erschreckten die Kinder von Steubenville; Hacker knackten das E-Mail-Konto des Polizeichefs von Steubenville und posteten ein Foto von ihm im G-String; und eine anonyme Drohung hatte die vorübergehende Schließung aller Schulen in Steubenville zur Folge.

Online-Moralwächter zensieren das Netz

Die Moralwächter, die sich wegen rassistischer oder sexistischer Äußerungen in ihren Wahn hineinsteigern, könnten bald jeden so bedrohen, dessen Meinung von der des Mobs abweicht. Heutzutage kann man bereits durch einen geschmacklosen Witz zur Zielscheibe werden. Morgen reicht dazu vielleicht schon ein berechtigter, aber unpopulärer Vorschlag wie etwa eine Steuer auf zuckerige Limonaden oder eine Frauenquote für Aufsichtsräte.

Online-Moralwächter „sorgen wahrscheinlich für mehr Zensur im Netz – vor allem, weil alternative Stimmen und Meinungen verstummen werden“, schrieb Hardaker in einer E-Mail. „Es gibt Menschen, die andere einschüchtern, bedrohen und letztlich zum Schweigen bringen und das alles als "Freie Meinungsäußerung" rechtfertigen, ohne überhaupt zu merken, wie ironisch das ist, da sie ja aktiv Zensur betreiben.“

Schon heute bringen die Denunzianten ihre Opfer fast unmittelbar zum Schweigen. Sacco hat ihre Social-Media-Konten gelöscht und ist damit eher die Regel als die Ausnahme. Doch die Rachefeldzüge des Mobs bringen nicht nur jene zum Schweigen, die einen Fehler gemacht haben, sondern schüchtern auch andere so ein, dass sie es nicht mehr wagen, die Stimme zu erheben. Saccos Erlebnisse sind ein Warnsignal für alle anderen, dass Abweichungen von der diffusen, aber strikt verteidigten Moral des Mobs nicht toleriert werden. Jeder kann sagen, was er will, solang es der Masse gefällt.

Reaktionen im Netz wirken sich auf das reale Leben aus

„Anders als bei Abschreckungsmethoden außerhalb des Internets gibt das öffentliche Anprangern einzelnen Menschen oder Gruppen die Möglichkeit festzulegen, was innerhalb eines bestimmten (sub-)kulturellen Kontexts akzeptabel ist und was nicht“, erklärte Dr. Whitney Phillips, Mitarbeiterin der soziologischen Fakultät der Humboldt State University, die sich mit Internetkultur befasst, im Dezember für „The Awl“. „Doch sie legen nicht nur Standards fest – gleichzeitig werden auch alle bestraft oder mit Strafen bedroht, die von der zuvor festgelegten Norm abweichen.“

Die spontane Reaktion der selbsternannten Moralhüter wirkt sich auch offline aus, da die Meinung von Freunden, Arbeitgebern und sogar Richtern durch die Vorverurteilung durch die Masse geprägt wird. Die Moralapostel im Netz „untergraben letztendlich echte Gerichtsprozesse, da eine objektive Beurteilung so kaum noch möglich ist“, warnt Hardaker. Der Grundton des Massenzorns, egal ob rational oder irrational, kann sich auf die Festlegung der angemessenen Strafe auswirken.

Auch Firmen werden von den digital erhobenen Mistgabeln schnell beeinflusst. Sacco hatte zum Beispiel schon vor ihrem Kommentar über Afrika eine Reihe beleidigender Tweets gepostet, darunter auch ein Verweis auf einen „erotischen Traum mit einem Autisten“.

Auch wenn das nicht ganz so geschmacklos ist wie die Aussage, die sie letztlich den Job gekostet hat, hat sich ihr Arbeitgeber nicht um diese unangebrachten Kommentare gekümmert, bis einer davon schließlich überall öffentlich bekannt wurde.

Wenn nur ein paar Stunden lang Gerüchte und Beschimpfungen online kursieren, kann das schon dazu führen, dass ein Angestellter für eine Firma nicht mehr tragbar wird oder ein Angeklagter für den Richter zum Verbrecher wird. Statt „unschuldig bis zum Beweis der Schuld“ heißt es heute „unschuldig bis zum Zorn des Online-Mobs“.

Übersetzt aus der Huffington Post USA von Bettina Koch. Hier geht's zum Original.

Solche Vorschläge waren deprimierend oft zu hören, nachdem die ehemalige Pressesprecherin des IAC-Konzerns vor einem Flug nach Südafrika ihren inzwischen berüchtigten Tweet absetzte: „Unterwegs nach Afrika. Hoffentlich kriege ich kein AIDS. Nur Spaß. Ich bin weiß!“ Dieser ignorante und geschmacklose Post kostete Sacco ihren Job und machte sie außerdem zum Ziel für den unaufhaltsamen Internet-Lynchmob. Im Internet wurden Unmengen äußerst plastischer, gemeiner Drohungen ausgesprochen: gegen Sacco, ihre Familie und sogar gegen Fremde, die einfach Mitleid mit ihr hatten.

Screenshot Twitter

Sacco hat ihre Konten bei Facebook, Twitter und Instagram inzwischen gelöscht und scheint sich vor der mistgabelschwingenden Meute zu verstecken, die sie gern „vergewaltigen und dir Aids ins Gesicht spritzen“ möchte, wie jemand auf Twitter schrieb.

My Africans gonn rape u n leave aids drippin down ya face RT @JustineSacco: Going to Africa. Hope I don't get AIDS. Just kidding. I'm white

— Dunkin Penderhughes (@DunkDa_G) 20. Dezember 2013

Die „Lynchmob-Mentalität“ sollte uns Angst machen

Die meisten von uns werden zwar niemals Ziel solcher Angriffe werden, dennoch sollte uns diese Lynchmob-Mentalität, die immer stärker, schneller und häufiger auftritt, zu denken geben. Die heftigen Reaktionen auf Sacco und viele andere vor ihr könnten zu einer Kultur der Selbstzensur führen, in der die freie Meinungsäußerung im Netz eingeschränkt wird und unkonventionelle Ansichten unterdrückt werden.

Wenn der allwissende Lynchmob stets bereitsteht, um jeden jederzeit zu denunzieren und anzugreifen, werden künftig keine unterschiedlichen Ideen mehr diskutiert werden, sondern nur noch harmlose Plattitüden ausgetauscht, denen jeder unbesorgt zustimmen kann.

Wer die Hetzkampagne gegen Sacco verurteilt, findet ihre Kommentare nicht automatisch gut. Die waren nicht nur ignorant, sondern für jemanden, der sein Geld mit Pressearbeit verdient, auch erstaunlich unbedarft.

Aber es gibt dennoch keine Rechtfertigung für dieses gewaltbereite, sexistische Feedback. (Tatsächlich halten Saccos Kritiker sich selbst wohl für über jede Kritik erhaben, solang sich ihr Zorn gegen jemanden richtet, den alle für böse halten.)

Die rücksichtslose Verurteilung von Menschen im Netz hält vielleicht andere künftig davon ab, eine Meinung auszusprechen, die auch nur leicht vom schlichten Schwarz-Weiß-Denken des Online-Mobs abweichen könnte. Claire Hardaker ist Dozentin an der Universität Lancaster und erforscht derartige emotionalen Wallungen im Internet. Sie erklärt, dass selbst ein „wohlmeinender“ Mob Fehler nach einfachen Regeln, inkonsequent und höchst emotional beurteilt.

Das Bauchgefühl gewinnt und führt dann zu extremen Reaktionen.

Mobbing oder freie Meinungsäußerung?

Diese Menschen behaupten zwar, sie würden einfach nur von ihrem Recht auf freie Meinungsäußerung Gebrauch machen, tatsächlich bringen sie aber jeden zum Schweigen, der ihre selbstgesetzten Grenzen überschreitet. Für die Opfer dieser brutalen Internetwächter kann die physische und digitale Bedrohung zu einer ernsten Gefahr werden.

Adria Richards, ehemalige Mitarbeiterin eines Unternehmens für E-Mail-Marketing, bezichtigte zwei Männer bei einer Konferenz, einen sexistischen Witz gemacht zu haben. Daraufhin rächten andere sich mit Morddrohungen und machten private Informationen über Richards öffentlich. Eine 22-Jährige, die sich zu Halloween als Opfer des Attentats beim Boston Marathon verkleidete, wurde gefeuert und erhielt Drohanrufe. Außerdem machten ihre persönlichen Daten und Nacktfotos online die Runde. Ein Fremder sagte ihrer besten Freundin, dass sie und ihr Kind sterben werden.

Die Einwohner von Steubenville in Ohio sagen, dass ihre Gemeinschaft von Online-Moralwächtern „zerstört“ wurde, die ihre eigene Form von Gerechtigkeit durchsetzen wollten, nachdem die Stadt nach Vergewaltigungsvorwürfen gegen zwei Teenager das Ziel von Internet-„Hacktivisten“ wurde. (Der Fall war, wie sich später herausstellte, deutlich komplizierter, als die Blogger das online wahrgenommen haben.) Vermummte versteckten sich im Gras und erschreckten die Kinder von Steubenville; Hacker knackten das E-Mail-Konto des Polizeichefs von Steubenville und posteten ein Foto von ihm im G-String; und eine anonyme Drohung hatte die vorübergehende Schließung aller Schulen in Steubenville zur Folge.

Online-Moralwächter zensieren das Netz

Die Moralwächter, die sich wegen rassistischer oder sexistischer Äußerungen in ihren Wahn hineinsteigern, könnten bald jeden so bedrohen, dessen Meinung von der des Mobs abweicht. Heutzutage kann man bereits durch einen geschmacklosen Witz zur Zielscheibe werden. Morgen reicht dazu vielleicht schon ein berechtigter, aber unpopulärer Vorschlag wie etwa eine Steuer auf zuckerige Limonaden oder eine Frauenquote für Aufsichtsräte.

Online-Moralwächter „sorgen wahrscheinlich für mehr Zensur im Netz – vor allem, weil alternative Stimmen und Meinungen verstummen werden“, schrieb Hardaker in einer E-Mail. „Es gibt Menschen, die andere einschüchtern, bedrohen und letztlich zum Schweigen bringen und das alles als "Freie Meinungsäußerung" rechtfertigen, ohne überhaupt zu merken, wie ironisch das ist, da sie ja aktiv Zensur betreiben.“

Schon heute bringen die Denunzianten ihre Opfer fast unmittelbar zum Schweigen. Sacco hat ihre Social-Media-Konten gelöscht und ist damit eher die Regel als die Ausnahme. Doch die Rachefeldzüge des Mobs bringen nicht nur jene zum Schweigen, die einen Fehler gemacht haben, sondern schüchtern auch andere so ein, dass sie es nicht mehr wagen, die Stimme zu erheben. Saccos Erlebnisse sind ein Warnsignal für alle anderen, dass Abweichungen von der diffusen, aber strikt verteidigten Moral des Mobs nicht toleriert werden. Jeder kann sagen, was er will, solang es der Masse gefällt.

Reaktionen im Netz wirken sich auf das reale Leben aus

„Anders als bei Abschreckungsmethoden außerhalb des Internets gibt das öffentliche Anprangern einzelnen Menschen oder Gruppen die Möglichkeit festzulegen, was innerhalb eines bestimmten (sub-)kulturellen Kontexts akzeptabel ist und was nicht“, erklärte Dr. Whitney Phillips, Mitarbeiterin der soziologischen Fakultät der Humboldt State University, die sich mit Internetkultur befasst, im Dezember für „The Awl“. „Doch sie legen nicht nur Standards fest – gleichzeitig werden auch alle bestraft oder mit Strafen bedroht, die von der zuvor festgelegten Norm abweichen.“

Die spontane Reaktion der selbsternannten Moralhüter wirkt sich auch offline aus, da die Meinung von Freunden, Arbeitgebern und sogar Richtern durch die Vorverurteilung durch die Masse geprägt wird. Die Moralapostel im Netz „untergraben letztendlich echte Gerichtsprozesse, da eine objektive Beurteilung so kaum noch möglich ist“, warnt Hardaker. Der Grundton des Massenzorns, egal ob rational oder irrational, kann sich auf die Festlegung der angemessenen Strafe auswirken.

Auch Firmen werden von den digital erhobenen Mistgabeln schnell beeinflusst. Sacco hatte zum Beispiel schon vor ihrem Kommentar über Afrika eine Reihe beleidigender Tweets gepostet, darunter auch ein Verweis auf einen „erotischen Traum mit einem Autisten“.

Auch wenn das nicht ganz so geschmacklos ist wie die Aussage, die sie letztlich den Job gekostet hat, hat sich ihr Arbeitgeber nicht um diese unangebrachten Kommentare gekümmert, bis einer davon schließlich überall öffentlich bekannt wurde.

Wenn nur ein paar Stunden lang Gerüchte und Beschimpfungen online kursieren, kann das schon dazu führen, dass ein Angestellter für eine Firma nicht mehr tragbar wird oder ein Angeklagter für den Richter zum Verbrecher wird. Statt „unschuldig bis zum Beweis der Schuld“ heißt es heute „unschuldig bis zum Zorn des Online-Mobs“.

Übersetzt aus der Huffington Post USA von Bettina Koch. Hier geht's zum Original.

Published on January 08, 2014 01:03

December 30, 2013

People Sext When They Don't Really Want To, Study Finds

“Not tonight, honey, I have a headache” can spare lovers from sex. But it won’t save them from sexts.

While headlines proclaim young adults are hooked on the joys of sexting, a forthcoming study examining the practice has found college-age sexters in committed relationships frequently engage in unwanted sexting, and will exchange explicit message or photos for reasons that have little to do with attraction or arousal.

Call it the “requisext”: an X-rated missive sent out of a sense of necessity or obligation, but not purely for pleasure. They're more common than many might realize, and are sent nearly as frequently by men and women.

The research, which will be published in February in the journal Computers in Human Behavior, reveals similarities between sexual behavior online and off. Previous research on couples’ sex lives has demonstrated that partners will willingly go along with sex, even when they’re not keen on it, for reasons that range from pleasing their partner to avoiding an argument. On smartphones and over email, e-sex happens for many of the same reasons.

Working to understand the frequency of “consensual but unwanted sexting” -- scientist-speak for “sexting when you’re not in the mood” -- psychologists at Indiana University-Purdue University For Wayne polled 155 undergraduates who were or had been in committed relationships on their sexting habits.

Fifty-five percent of the female respondents said they had previously engaged in unwanted sexting, while 48 percent of men had done the same. Those numbers are surprisingly similar to previous findings on so-called “compliant sexual activity”: A 1994 report determined that 55 percent of American women and 35 percent of American men had ever engaged in consensual but unwanted sex.

But while women have typically far outnumbered men in having unwanted sexual activity the old-fashioned way, the rates of requisexting were not drastically higher among women, the study found. In this case, equality for the sexes means near-equality in unwanted sexting.

The authors of the article argued "gender-role expectations" could be to blame. Men might be more likely to agree to undesired sexting because doing so is "relatively easy and does not require them to invest more into the relationship." Women in turn might be discouraged from virtual sex because it fails to help them attain their relationship "goals," the authors hypothesized.

So what makes people feel the need to requisext -- especially when the evidence can so easily come back to haunt them?

The survey's respondents were asked to rate ten possible motivations for their begrudging sexts, ranging from “I was bored” to “I was taking drugs.”

People most frequently consented to unwanted sexting because they sought to flirt, engage in foreplay, satisfy a partner’s need or foster intimacy in their relationship. The researchers also found that people who were anxious about their relationships -- specifically, who feared abandonment by or alienation from their lovers -- were more likely to be requisexters. Digital communication could be “especially challenging” for these anxious lovers, who might increase their sexting in an attempt to make distant lovers seem closer, the study's authors speculated.

On the other hand, those sick of requisexting might soon be coming up with some clever "outs." Next time, just claim you have a thumbache.

While headlines proclaim young adults are hooked on the joys of sexting, a forthcoming study examining the practice has found college-age sexters in committed relationships frequently engage in unwanted sexting, and will exchange explicit message or photos for reasons that have little to do with attraction or arousal.

Call it the “requisext”: an X-rated missive sent out of a sense of necessity or obligation, but not purely for pleasure. They're more common than many might realize, and are sent nearly as frequently by men and women.

The research, which will be published in February in the journal Computers in Human Behavior, reveals similarities between sexual behavior online and off. Previous research on couples’ sex lives has demonstrated that partners will willingly go along with sex, even when they’re not keen on it, for reasons that range from pleasing their partner to avoiding an argument. On smartphones and over email, e-sex happens for many of the same reasons.

Working to understand the frequency of “consensual but unwanted sexting” -- scientist-speak for “sexting when you’re not in the mood” -- psychologists at Indiana University-Purdue University For Wayne polled 155 undergraduates who were or had been in committed relationships on their sexting habits.

Fifty-five percent of the female respondents said they had previously engaged in unwanted sexting, while 48 percent of men had done the same. Those numbers are surprisingly similar to previous findings on so-called “compliant sexual activity”: A 1994 report determined that 55 percent of American women and 35 percent of American men had ever engaged in consensual but unwanted sex.

But while women have typically far outnumbered men in having unwanted sexual activity the old-fashioned way, the rates of requisexting were not drastically higher among women, the study found. In this case, equality for the sexes means near-equality in unwanted sexting.

The authors of the article argued "gender-role expectations" could be to blame. Men might be more likely to agree to undesired sexting because doing so is "relatively easy and does not require them to invest more into the relationship." Women in turn might be discouraged from virtual sex because it fails to help them attain their relationship "goals," the authors hypothesized.

So what makes people feel the need to requisext -- especially when the evidence can so easily come back to haunt them?

The survey's respondents were asked to rate ten possible motivations for their begrudging sexts, ranging from “I was bored” to “I was taking drugs.”

People most frequently consented to unwanted sexting because they sought to flirt, engage in foreplay, satisfy a partner’s need or foster intimacy in their relationship. The researchers also found that people who were anxious about their relationships -- specifically, who feared abandonment by or alienation from their lovers -- were more likely to be requisexters. Digital communication could be “especially challenging” for these anxious lovers, who might increase their sexting in an attempt to make distant lovers seem closer, the study's authors speculated.

On the other hand, those sick of requisexting might soon be coming up with some clever "outs." Next time, just claim you have a thumbache.

Published on December 30, 2013 11:47

December 27, 2013

Why We Should All Fear The Righteous Online Mob

Justine Sacco ought to be tortured, shot and raped, preferably by someone with HIV, for what she said on Twitter -- at least according to a disturbing number of social media users.

Such suggestions were depressingly common in the week after Sacco, a former IAC public relations executive, sent a now-notorious tweet just before boarding a plane to South Africa: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” The ignorant and distasteful post cost Sacco her job and has made her a target for the Internet’s unstoppable “shame army.” People online have unleashed a barrage of graphic and abusive threats against Sacco, her family and even strangers who’ve expressed sympathy for her.

Sacco, whose Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts have since disappeared, seems to have retreated from the pitchfork-wielding mass keen to “rape u n leave aids drippin down ya face,” as one person wrote on Twitter.

Though most of us will never be targeted in this way, we all have reason to fear this breed of mob vigilantism, which has struck with increasing force, speed and regularity. The violent response to Sacco, and many others before her, risks instilling a culture of self-censorship that stifles free expression and mutes unconventional opinions online. With the all-seeing shame army standing at the ready to denounce and attack anyone at any time, debating differing ideas could give way to exchanging watered-down platitudes that garner mob approval and everyone can “like.”

Condemning the bile aimed at Sacco isn’t the same as endorsing her remarks, which were both ignorant and astonishingly clueless for somebody whose job was generating positive press. But there is no justification for the nature of the violent, sexist blowback. (In fact, Sacco's harassers seem emboldened by the assumption that they’re above criticism so long as they’re condemning a person others agree is bad.)

The ruthless public shaming people like Sacco face online may dissuade other people from any speech that diverges, even slightly, from the mob’s black-and-white moral code. Dr. Claire Hardaker, a lecturer at Lancaster University researching aggression online, points out that even a "well-meaning" mob judges fault in a simplistic, inconsistent and highly emotional fashion. Gut reactions win, then give way to extreme responses.

Though the menaces may claim they're just exercising their right to free speech, they're actually muting the voices of anyone who dares cross the mob's "party line." For the targets of violent Internet vigilantism, the physical and digital can meld in ways that jeopardize peoples' livelihoods, or even their safety.

When Adria Richards, then an employee at an email marketing company, called out two men at a tech conference for what she considered a sexist joke, others lashed out with death threats and exposed her private information. A 22-year-old who dressed as a Boston marathon victim for Halloween was fired, received menacing phone calls, had her personal details leaked and had nude pictures of herself circulated online. A stranger told her best friend she and her child would be killed.

The residents of Steubenville, Ohio, a town that became the target of Internet “hacktivists” following rape charges against two teenage boys, described their community as “destroyed” by online vigilantes pushing for what they considered justice. (The case, later accounts suggested, was far more complicated than bloggers online seemed to realize.) Masked strangers spooked Steubenville children by hiding in their lawn; hackers broke into the Steubenville police chief's email, then posted a photo of him in a G-string; and an anonymous threat temporarily shut down Steubenville schools.

The vigilantes who have been whipped into a frenzy over racist tweets -- or accusations of sexism -- could, before long, unleash the same abuse on anyone who expresses an opinion with which the mob disagrees. Today, a tasteless joke could make you a target. Tomorrow, it may be an unpopular, but valid, idea -- like taxing soft drinks, or instituting quotas for female board members.

Online vigilantism "is likely to lead to a greater culture of censorship -- in particular, the stifling of alternative voices and opinions," Hardaker wrote in an email. “[W]e find people defending this strategy of intimidating, threatening, and ultimately silencing others as ‘free speech,’ seemingly oblivious to the irony that in doing so, they are actively engaged in censorship."

Already the denouncers succeed almost immediately in silencing their targets. Closing her social media accounts makes Sacco the rule, not the exception. But the mass vengeance not only muzzles those who’ve done something wrong, it scares others into a kind of submissive silence. Sacco’s experience warns everyone else that there is no tolerance for deviance from the amorphous, but rigidly defended, ethics of the mob. You can say what you please, so long as it pleases the crowd.

“Like more traditional offline deterrents ... online shaming allows certain individuals or groups to model what is and what is not acceptable within a specific (sub)cultural context,” Dr. Whitney Phillips, a faculty associate in Humboldt State University's sociology department researching Internet culture, wrote in The Awl last December. “But not just model -- the second (and simultaneous) half of that equation is punishing, or threatening to punish, anyone who deviates from whatever established norm.”

The snap judgment of the self-appointed shame army extends offline, where the perceptions of friends, employers and even jurors are tainted by the condemnation of the crowd. The online vigilantism “effectively undermines actual judicial processes by making it nearly impossible for cases that go to court to get a fair hearing,” warned Hardaker. No matter how rational or irrational, the tenor of mob outrage can overwhelm measured responses.

Companies are easily swayed by the digital pitchforks. Sacco, for example, had posted a slew of offensive tweets before her comment about Africa last week, including one reference to her"sex dream about an autistic kid." Although arguably less egregious than the message that got her fired, her employer didn’t seem to balk at her off-color comments until her post became news. People can become a liability for companies, or a criminal in the eyes of jurors, after a few hours of rumors and outrage online. Innocent until proven guilty has become innocent until proven viral.

Such suggestions were depressingly common in the week after Sacco, a former IAC public relations executive, sent a now-notorious tweet just before boarding a plane to South Africa: “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!” The ignorant and distasteful post cost Sacco her job and has made her a target for the Internet’s unstoppable “shame army.” People online have unleashed a barrage of graphic and abusive threats against Sacco, her family and even strangers who’ve expressed sympathy for her.

Sacco, whose Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts have since disappeared, seems to have retreated from the pitchfork-wielding mass keen to “rape u n leave aids drippin down ya face,” as one person wrote on Twitter.

Though most of us will never be targeted in this way, we all have reason to fear this breed of mob vigilantism, which has struck with increasing force, speed and regularity. The violent response to Sacco, and many others before her, risks instilling a culture of self-censorship that stifles free expression and mutes unconventional opinions online. With the all-seeing shame army standing at the ready to denounce and attack anyone at any time, debating differing ideas could give way to exchanging watered-down platitudes that garner mob approval and everyone can “like.”

Condemning the bile aimed at Sacco isn’t the same as endorsing her remarks, which were both ignorant and astonishingly clueless for somebody whose job was generating positive press. But there is no justification for the nature of the violent, sexist blowback. (In fact, Sacco's harassers seem emboldened by the assumption that they’re above criticism so long as they’re condemning a person others agree is bad.)

The ruthless public shaming people like Sacco face online may dissuade other people from any speech that diverges, even slightly, from the mob’s black-and-white moral code. Dr. Claire Hardaker, a lecturer at Lancaster University researching aggression online, points out that even a "well-meaning" mob judges fault in a simplistic, inconsistent and highly emotional fashion. Gut reactions win, then give way to extreme responses.

Though the menaces may claim they're just exercising their right to free speech, they're actually muting the voices of anyone who dares cross the mob's "party line." For the targets of violent Internet vigilantism, the physical and digital can meld in ways that jeopardize peoples' livelihoods, or even their safety.

When Adria Richards, then an employee at an email marketing company, called out two men at a tech conference for what she considered a sexist joke, others lashed out with death threats and exposed her private information. A 22-year-old who dressed as a Boston marathon victim for Halloween was fired, received menacing phone calls, had her personal details leaked and had nude pictures of herself circulated online. A stranger told her best friend she and her child would be killed.

The residents of Steubenville, Ohio, a town that became the target of Internet “hacktivists” following rape charges against two teenage boys, described their community as “destroyed” by online vigilantes pushing for what they considered justice. (The case, later accounts suggested, was far more complicated than bloggers online seemed to realize.) Masked strangers spooked Steubenville children by hiding in their lawn; hackers broke into the Steubenville police chief's email, then posted a photo of him in a G-string; and an anonymous threat temporarily shut down Steubenville schools.

The vigilantes who have been whipped into a frenzy over racist tweets -- or accusations of sexism -- could, before long, unleash the same abuse on anyone who expresses an opinion with which the mob disagrees. Today, a tasteless joke could make you a target. Tomorrow, it may be an unpopular, but valid, idea -- like taxing soft drinks, or instituting quotas for female board members.

Online vigilantism "is likely to lead to a greater culture of censorship -- in particular, the stifling of alternative voices and opinions," Hardaker wrote in an email. “[W]e find people defending this strategy of intimidating, threatening, and ultimately silencing others as ‘free speech,’ seemingly oblivious to the irony that in doing so, they are actively engaged in censorship."

Already the denouncers succeed almost immediately in silencing their targets. Closing her social media accounts makes Sacco the rule, not the exception. But the mass vengeance not only muzzles those who’ve done something wrong, it scares others into a kind of submissive silence. Sacco’s experience warns everyone else that there is no tolerance for deviance from the amorphous, but rigidly defended, ethics of the mob. You can say what you please, so long as it pleases the crowd.

“Like more traditional offline deterrents ... online shaming allows certain individuals or groups to model what is and what is not acceptable within a specific (sub)cultural context,” Dr. Whitney Phillips, a faculty associate in Humboldt State University's sociology department researching Internet culture, wrote in The Awl last December. “But not just model -- the second (and simultaneous) half of that equation is punishing, or threatening to punish, anyone who deviates from whatever established norm.”

The snap judgment of the self-appointed shame army extends offline, where the perceptions of friends, employers and even jurors are tainted by the condemnation of the crowd. The online vigilantism “effectively undermines actual judicial processes by making it nearly impossible for cases that go to court to get a fair hearing,” warned Hardaker. No matter how rational or irrational, the tenor of mob outrage can overwhelm measured responses.

Companies are easily swayed by the digital pitchforks. Sacco, for example, had posted a slew of offensive tweets before her comment about Africa last week, including one reference to her"sex dream about an autistic kid." Although arguably less egregious than the message that got her fired, her employer didn’t seem to balk at her off-color comments until her post became news. People can become a liability for companies, or a criminal in the eyes of jurors, after a few hours of rumors and outrage online. Innocent until proven guilty has become innocent until proven viral.

Published on December 27, 2013 10:29

December 23, 2013

The Definitive Tech Books Of 2013

Silicon Valley keeps spawning micro-storytelling genres -- from six-second Vines to 140-character tweets -- that are each more popular than the next. But that hardly means those mini-formats can properly capture the controversies, personalities, ramifications and dangers of the tech world's many characters and their creations.

For that, we can turn to another invention that compiles tens of thousands of discreet pieces of data into a kind of "Facebook for words": books.

Here are eight books that should be required reading for anyone keen to explore where technology is taking us, where it came from or what it's doing to us.

Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era

James Barrat

TLDR: Artificial intelligence won’t just drive our cars, choose our clothes and answer our questions: Some day it may destroy us, argues Barrat. Companies like Google and Facebook have spent 2013 expanding their army of artificial intelligence experts, which makes Barrat's book such a necessary read. Barrat looks into the future and, drawing on insights from leading researchers and computer scientists, explains in straightforward prose where our quest for true AI could take us. After artificial intelligence comes human-level artificial general intelligence, followed by artificial super-intelligence -- at which point the bots’ brains will leave ours in the dust. At that point, our survival may be up to the algorithms.

Smarter Than You Think: How Technology Is Changing Our Minds For the Better

Clive Thompson

TLDR: Technology isn’t rotting your brain, it’s augmenting it. Interweaving personal anecdotes and deeply-reported profiles, Thompson makes a thoughtful, nuanced case for why tech is enhancing human abilities, even as it alters how we think. Thompson is refreshingly candid about how complex these issues are, and it's the rare tech tome that avoids the trap of reducing an argument to a soundbite that’s either blindly technoutopian, or nightmarishly apocalyptic.

To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism

Evgeny Morozov

TLDR: Those tech companies that claim they're “saving the world?” They’re not. Morozov unpacks the rarely-aired risks of letting Silicon Valley continue its "amelioration orgy" and the consequences of a "solutionism" mindset that believes technology can (and should) fix everything. While patting itself on the back, Silicon Valley has pursued a quest to eradicate the evils of imperfection, ambiguity, opacity and disorder. But these "evils" are actually fundamental freedoms, Morozov argues. And if we eliminate them, we eliminate freedom as well. It's a book that needs to be read, particularly by those who disagree with Morozov’s thesis.

Lean In: Women, Work and the Will to Lead

Shery Sandberg

TLDR: Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg has this advice for working women, which she hopes will help them rise through the ranks: Don’t leave before you leave; make your partner a real partner; sit at the table; ask for what you want; make mentors, don’t request them; be confident; and don’t expect to have it all. If you've seen her famous 2010 TED Talk, that should sound familiar. Yet that shouldn't discourage you from reading Lean In -- which discusses that and more in greater depth. Though Sandberg's life is one of privilege and the book provoked some controversy, Lean In has thought-provoking and practical recommendations for both men and women, experienced managers and recent grads.

Writing on the Wall: Social Media - The First 2,000 Years

Tom Standage

TLDR: “New Media” isn’t so new. In fact, it’s very, very old. That’s a crude summary of Standage’s argument, which draws convincing links between the tweets of the today and the papyrus scrolls or printing presses of the past. As Standage sees it, Martin Luther’s "95 Theses" and Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” were the first viral hits of their time. Writing on the Wall will change the way you see your Snapchats, as it reveals how social media satisfies a deep-seated human itch that is ancient and fundamental to who we are.

Status Update: Celebrity, Publicity, and Branding in the Social Media Age

Alice Marwick

TLDR: Social media didn’t solve our social ills -- it just moved them to a different format. Relying on extensive field research and profiles of the Silicon Valley "technorati," Marwick’s Status Update explores what kind of people we become online, as we squeeze ourselves into Facebook status updates and lifecast on Twitter. As she asks in the introduction, “What types of selves are people encouraged to create and promote while using popular technologies like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube?” Anxious ones, constantly vying for status and self-promoting, she concludes.

The Everything Store: Jeff Bezos and the Age of Amazon

Brad Stone

TLDR: The “Everything Store” offers everything Amazon, from the tale of Bezos' biological father, to Bezos' battles with publishers. Bezos' wife gave Stone's work a one-star review on Amazon. (She said it contained "too many inaccuracies" and pointed out that Bezos never granted a formal interview for the book.) In spite of her critique, "The Everything Store" does deliver a detailed and revealing look at the rise of a tech behemoth, and hints at where the drone-building, grocery-delivering, fine-art-selling operation will go. Spoiler: Amazon has its sights set on, well, everything.

Hatching Twitter: A True Story of Money, Power, Friendship, and Betrayal

Nick Bilton

TLDR: It’s a marvel Twitter made it. "Hatching Twitter," which reads almost like a screenplay, details the infighting, backstabbing, history re-writing and limelight-stealing of Twitter’s co-founders -- and its “forgotten” creator, Noah Glass.

Also On Our Reading List:

Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution

Fred Vogelstein

Who Owns the Future?

Jaron Lanier

The Circle

Dave Eggers

Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety

Eric Schlosser

For that, we can turn to another invention that compiles tens of thousands of discreet pieces of data into a kind of "Facebook for words": books.

Here are eight books that should be required reading for anyone keen to explore where technology is taking us, where it came from or what it's doing to us.

Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era

James Barrat