Bianca Bosker's Blog, page 4

April 15, 2014

Glass Warfare: How Google's Headgear Problems Went From Bad To Worse

Just in case Americans aren’t signing enough big checks on April 15, Google is celebrating Tax Day by giving the nation one day -- and one day only -- to purchase its $1,500 Google Glass forehead computer. Thus far, it seems people have done a superb job containing their excitement.

We always knew Glass, with its vaguely orthodontic design, would be a tough sell. Yet in the thirteen months since the device first appeared on American brows, Google has actually lost ground: Getting people to embrace the Internet-connected head camera has become more difficult, not less. And this is after an extended PR blitz, in which Google placed Glass on models in Vogue, refashioned it on sleek designer frames and showcased Glass in the hands of famous chefs, DJs and fashion designers.

In the beginning, Glass’ biggest sin was looking weird. Now, Glass is both physically unattractive and morally suspect. Glass has transformed into a symbol of the class warfare that’s erupted in San Francisco as residents protest the high prices, evictions and gentrification brought by an infusion of Silicon Valley cash. Glass, with its high pricetag and privacy threat, has come to represent everything San Francisco’s activists resent about the tech industry: privilege, profligate living and a disrupt-or-bust mentality that prioritizes progress for a few over the well-being of many. No stylish Warby Parker frames can easily fix that.

Wearing Glass is no longer just a sign of a dubious fashion sense. Donning Glass, no matter who you are under the metal frame, taints you as one of them -- one of the rich people destroying the fabric of the city, or one of the creepy Glassholes who likes to secretly record strangers from across the roof. Probably both. Such stereotypes turn Glass carriers into a target.

In San Francisco this past weekend, a Business Insider reporter covering a protest against Google had his Glass ripped from his face and smashed on the sidewalk. A few weeks before, a woman who wore Glass into a dive bar on Haight Street got the middle finger from fellow patrons, was told she was “killing the city,” and had her forehead-computer grabbed off her head by a stranger, who disappeared with the device but later returned it.

“When I saw her wearing the glasses,” the woman who flipped off the Glass owner told the New Yorker, “all I could think of was my friends who are being pushed out of the city.”

Google would like it very much if the world would just see Glass as a friendly device that’s “getting technology out of the way” while helping you “explore your world.” Instead, Glass has come to look more like an expensive toy for nerds with money to burn. The company has tried to smooth things over by giving its Explorers -- the 10,000-odd people invited to purchase early versions of Glass -- an etiquette guide to follow, with instructions like “respect others” and don't “be creepy or rude.”

But what Google hasn’t yet done is offer people a persuasive reason for why they need to wear Glass. Even those of us who haven’t signed a four-figure check know that leaving Glass at home doesn’t compare to forgetting an iPhone on the kitchen counter. So far, the only killer application for Glass is showing people that you’re wearing Glass.

Even with a growing number of Glass apps, there’s not much people can do with the fancy spectacles that they couldn’t do more quickly or seamlessly with their phones. To many, Glass still looks like an optional accessory. When Glass owners are challenged to defend why they’re using the device, in spite of the discomfort it might cause people around them, the wearers don’t have a compelling reply. The assumption becomes that they’re wearing Glass to show off, further cementing its dubious, status-symbol reputation.

Can Glass recover? Google is trying for a comeback, and has made a big show lately of putting Glass into the hands of the people who dedicate their lives to making people feel better: Doctors, firefighters, teachers.

If that doesn't work, Google also has a backup plan to make Glass less visible. This week, it filed a patent for technology that could put cameras on contact lenses.

We always knew Glass, with its vaguely orthodontic design, would be a tough sell. Yet in the thirteen months since the device first appeared on American brows, Google has actually lost ground: Getting people to embrace the Internet-connected head camera has become more difficult, not less. And this is after an extended PR blitz, in which Google placed Glass on models in Vogue, refashioned it on sleek designer frames and showcased Glass in the hands of famous chefs, DJs and fashion designers.

In the beginning, Glass’ biggest sin was looking weird. Now, Glass is both physically unattractive and morally suspect. Glass has transformed into a symbol of the class warfare that’s erupted in San Francisco as residents protest the high prices, evictions and gentrification brought by an infusion of Silicon Valley cash. Glass, with its high pricetag and privacy threat, has come to represent everything San Francisco’s activists resent about the tech industry: privilege, profligate living and a disrupt-or-bust mentality that prioritizes progress for a few over the well-being of many. No stylish Warby Parker frames can easily fix that.

Wearing Glass is no longer just a sign of a dubious fashion sense. Donning Glass, no matter who you are under the metal frame, taints you as one of them -- one of the rich people destroying the fabric of the city, or one of the creepy Glassholes who likes to secretly record strangers from across the roof. Probably both. Such stereotypes turn Glass carriers into a target.

In San Francisco this past weekend, a Business Insider reporter covering a protest against Google had his Glass ripped from his face and smashed on the sidewalk. A few weeks before, a woman who wore Glass into a dive bar on Haight Street got the middle finger from fellow patrons, was told she was “killing the city,” and had her forehead-computer grabbed off her head by a stranger, who disappeared with the device but later returned it.

“When I saw her wearing the glasses,” the woman who flipped off the Glass owner told the New Yorker, “all I could think of was my friends who are being pushed out of the city.”

Google would like it very much if the world would just see Glass as a friendly device that’s “getting technology out of the way” while helping you “explore your world.” Instead, Glass has come to look more like an expensive toy for nerds with money to burn. The company has tried to smooth things over by giving its Explorers -- the 10,000-odd people invited to purchase early versions of Glass -- an etiquette guide to follow, with instructions like “respect others” and don't “be creepy or rude.”

But what Google hasn’t yet done is offer people a persuasive reason for why they need to wear Glass. Even those of us who haven’t signed a four-figure check know that leaving Glass at home doesn’t compare to forgetting an iPhone on the kitchen counter. So far, the only killer application for Glass is showing people that you’re wearing Glass.

Even with a growing number of Glass apps, there’s not much people can do with the fancy spectacles that they couldn’t do more quickly or seamlessly with their phones. To many, Glass still looks like an optional accessory. When Glass owners are challenged to defend why they’re using the device, in spite of the discomfort it might cause people around them, the wearers don’t have a compelling reply. The assumption becomes that they’re wearing Glass to show off, further cementing its dubious, status-symbol reputation.

Can Glass recover? Google is trying for a comeback, and has made a big show lately of putting Glass into the hands of the people who dedicate their lives to making people feel better: Doctors, firefighters, teachers.

If that doesn't work, Google also has a backup plan to make Glass less visible. This week, it filed a patent for technology that could put cameras on contact lenses.

Published on April 15, 2014 09:46

April 11, 2014

Meet The Mormon Church's First Online-Only Missionary

Can people feel the Holy Sprit through a screen? Or accept a new faith via Facebook?

Tyson Boardman had no idea. No one did. But as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' first -- and, back then, only -- online missionary, it was his job to find out whether salvation could be delivered over broadband.

When Boardman first sat down at a cubicle in the church's Provo, Utah, mission six years ago, 52,000 other Mormon missionaries were also trying to convert new members to their faith. These traditional missionaries were able to knock on doors, sit in living rooms and look people in the eye while explaining why their Lord was the one true Lord. But Tyson had only his keyboard. Touchy-feely meant, at the very best, emoticons.

Boardman was the first missionary recruited for the Mormon church's unprecedented experiment in Internet-based proselytizing, which would turn out to be a wildly successful undertaking and is the subject of a new feature story I wrote for The Huffington Post. This past June, thanks in large part to the wave of converts added by missionaries following Boardman's lead, the church announced it would put previously banned tools like Facebook and text messaging into the hands of all its missionaries.

"I remember being in a meeting with the church and they said, 'There are a billion people on Facebook, and God has always promised he'll send his missionaries where his people are. So of course he'll send his missionaries to Facebook,'" says Emilee Cluff, a former missionary who served between 2011 and 2012 at a mission testing a hybrid of online and offline evangelizing.

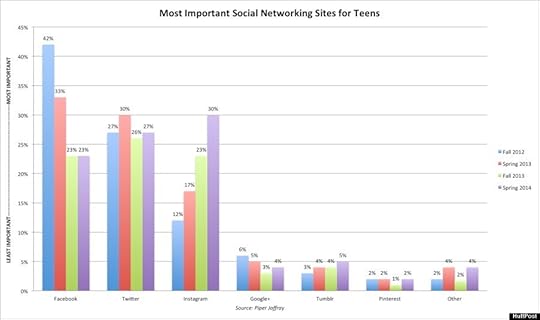

Tyson Boardman at his computer doing online missionary work.

As the inaugural Internet-only Mormon missionary, Boardman's experience offers a glimpse into the very beginning of this e-proselytizing push, which was an accidental success that surprised even its early advocates.

It all started at Provo's Missionary Training Center, a bootcamp for outbound missionaries housed in complex of squat, tan buildings that, at least according to one missionary, look "kind of like a prison." Boardman, then 19, had dreamed his entire life of pinning a church nametag to his breast and setting forth with thousands of other missionaries to proclaim "the good news of His restored gospel" to the world. But Boardman was born with muscular dystrophy, which prevented him from doing the door-to-door preaching that's become a trademark of the Mormon church, and there were doubts he'd be able to serve at all.

Had Boardman applied for his mission just a few months before he did, in early 2008, he probably wouldn't have. "It was just good timing," Boardman's mother explains in a 2010 video on her son's service. That spring, church leaders had decided to test putting more manpower into staffing an online chat service they'd launched as a kind of PR tool to correct myths about Mormonism. And so Boardman, with little idea of what to expect, left his studies in electrical engineering at Brigham Young University for a two-year stint in Provo.

Mormon missionaries walk through the halls at the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah. (AP/Rick Bowmer)

He was called by the church to message one-on-one with anyone who clicked the "chat" tab on Mormon.org, the church's public-facing online home that debuted just before Utah hosted the 2002 Olympics. Since he was the sole missionary of his kind when he arrived, he lived alone in an apartment near the Missionary Training Center. As more young men were tapped for the online work, the missionaries were moved to dorms at the center.

Boardman followed the same strict routine as other missionaries around the world. He'd wake at 7:30 a.m., then exercise, pray and plan the day’s agenda with his partner. He'd be at his desk at 11, dressed in the traditional suit-and-tie uniform, and aside from an hour for lunch and dinner, he’d be online at his computer until around 10 p.m. each evening. He’d have an hour to review his work that day and plan his goals for the next before lights out at 11:30 p.m.

Juggling between 50 and 60 conversations each day, Boardman chatted with a mix of trolls spouting abuse, spirited debaters challenging him to defend the church's view of homosexuality (Boardman served during California's Prop 8 debate) and lonely people who just wanted someone to talk to.

The role of these online missionaries was to "find, teach and prepare investigators" -- what Mormons call potential converts -- "to meet local members and missionaries by helping them read the Book of Mormon, pray and attend church," according to an online presentation created by Daniel Ware, a manager at the Missionary Training Center who helped champion the online proselytizing.

A Prezi presentation created by Ware, a manager at the Missionary Training Center who helped bring Boardman and other online missionaries to the Referral Center Mission.

By 2010, when Boardman finished his mission, some 15 other missionaries had joined him at the center. They were fielding an average of 2,000 to 3,000 chats a day, according to an LDS Living magazine story that appeared at the time. The Salt Lake Tribune reported in July 2010 that online evangelists were, each week, taking an average of 10,000 chats, referring 3,500 individuals to missionaries for in-person meetings and teaching 1,200 people the lessons that are a prerequisite for baptism. ("The church is big on record-keeping," says Cluff, who notes the missionaries "did report numbers every week" on how many people they taught online and how many they baptized.)

By then, a few more missions across the country -- beginning with one in Rochester, N.Y. -- had also begun dabbling in Facebook, requiring traditional missionaries to supplement their offline work with an hour a day online.

Certain mission leaders were still wary of the new technology. According to former missionaries, one mission president in California considered the female missionaries "more trustworthy," and he gave these "Sisters" immediate access to Facebook, while making the boys prove over weeks, or even months, they deserved it.

And yes, Boardman ultimately discovered, Internet investigators could feel the Holy Spirit, a sign they believed in the principles of the Mormon faith.

"It was unique to recognize that even in something as impersonal as chat," says Boardman, "We were able to develop such close and personal relationships with them and also recognize that they felt the Holy Ghost as we talked with them."

Boardman estimates that he helped convert 30 to 40 new members during his time in Provo, about five times the average.

One has the sense the total might have been higher had it not been for a logistics snag: Says Boardman, "There's no way to baptize right now via the Internet."

Tyson Boardman had no idea. No one did. But as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' first -- and, back then, only -- online missionary, it was his job to find out whether salvation could be delivered over broadband.

When Boardman first sat down at a cubicle in the church's Provo, Utah, mission six years ago, 52,000 other Mormon missionaries were also trying to convert new members to their faith. These traditional missionaries were able to knock on doors, sit in living rooms and look people in the eye while explaining why their Lord was the one true Lord. But Tyson had only his keyboard. Touchy-feely meant, at the very best, emoticons.

Boardman was the first missionary recruited for the Mormon church's unprecedented experiment in Internet-based proselytizing, which would turn out to be a wildly successful undertaking and is the subject of a new feature story I wrote for The Huffington Post. This past June, thanks in large part to the wave of converts added by missionaries following Boardman's lead, the church announced it would put previously banned tools like Facebook and text messaging into the hands of all its missionaries.

"I remember being in a meeting with the church and they said, 'There are a billion people on Facebook, and God has always promised he'll send his missionaries where his people are. So of course he'll send his missionaries to Facebook,'" says Emilee Cluff, a former missionary who served between 2011 and 2012 at a mission testing a hybrid of online and offline evangelizing.

Tyson Boardman at his computer doing online missionary work.

As the inaugural Internet-only Mormon missionary, Boardman's experience offers a glimpse into the very beginning of this e-proselytizing push, which was an accidental success that surprised even its early advocates.

It all started at Provo's Missionary Training Center, a bootcamp for outbound missionaries housed in complex of squat, tan buildings that, at least according to one missionary, look "kind of like a prison." Boardman, then 19, had dreamed his entire life of pinning a church nametag to his breast and setting forth with thousands of other missionaries to proclaim "the good news of His restored gospel" to the world. But Boardman was born with muscular dystrophy, which prevented him from doing the door-to-door preaching that's become a trademark of the Mormon church, and there were doubts he'd be able to serve at all.

Had Boardman applied for his mission just a few months before he did, in early 2008, he probably wouldn't have. "It was just good timing," Boardman's mother explains in a 2010 video on her son's service. That spring, church leaders had decided to test putting more manpower into staffing an online chat service they'd launched as a kind of PR tool to correct myths about Mormonism. And so Boardman, with little idea of what to expect, left his studies in electrical engineering at Brigham Young University for a two-year stint in Provo.

Mormon missionaries walk through the halls at the Missionary Training Center in Provo, Utah. (AP/Rick Bowmer)

He was called by the church to message one-on-one with anyone who clicked the "chat" tab on Mormon.org, the church's public-facing online home that debuted just before Utah hosted the 2002 Olympics. Since he was the sole missionary of his kind when he arrived, he lived alone in an apartment near the Missionary Training Center. As more young men were tapped for the online work, the missionaries were moved to dorms at the center.

Boardman followed the same strict routine as other missionaries around the world. He'd wake at 7:30 a.m., then exercise, pray and plan the day’s agenda with his partner. He'd be at his desk at 11, dressed in the traditional suit-and-tie uniform, and aside from an hour for lunch and dinner, he’d be online at his computer until around 10 p.m. each evening. He’d have an hour to review his work that day and plan his goals for the next before lights out at 11:30 p.m.

Juggling between 50 and 60 conversations each day, Boardman chatted with a mix of trolls spouting abuse, spirited debaters challenging him to defend the church's view of homosexuality (Boardman served during California's Prop 8 debate) and lonely people who just wanted someone to talk to.

The role of these online missionaries was to "find, teach and prepare investigators" -- what Mormons call potential converts -- "to meet local members and missionaries by helping them read the Book of Mormon, pray and attend church," according to an online presentation created by Daniel Ware, a manager at the Missionary Training Center who helped champion the online proselytizing.

A Prezi presentation created by Ware, a manager at the Missionary Training Center who helped bring Boardman and other online missionaries to the Referral Center Mission.

By 2010, when Boardman finished his mission, some 15 other missionaries had joined him at the center. They were fielding an average of 2,000 to 3,000 chats a day, according to an LDS Living magazine story that appeared at the time. The Salt Lake Tribune reported in July 2010 that online evangelists were, each week, taking an average of 10,000 chats, referring 3,500 individuals to missionaries for in-person meetings and teaching 1,200 people the lessons that are a prerequisite for baptism. ("The church is big on record-keeping," says Cluff, who notes the missionaries "did report numbers every week" on how many people they taught online and how many they baptized.)

By then, a few more missions across the country -- beginning with one in Rochester, N.Y. -- had also begun dabbling in Facebook, requiring traditional missionaries to supplement their offline work with an hour a day online.

Certain mission leaders were still wary of the new technology. According to former missionaries, one mission president in California considered the female missionaries "more trustworthy," and he gave these "Sisters" immediate access to Facebook, while making the boys prove over weeks, or even months, they deserved it.

And yes, Boardman ultimately discovered, Internet investigators could feel the Holy Spirit, a sign they believed in the principles of the Mormon faith.

"It was unique to recognize that even in something as impersonal as chat," says Boardman, "We were able to develop such close and personal relationships with them and also recognize that they felt the Holy Ghost as we talked with them."

Boardman estimates that he helped convert 30 to 40 new members during his time in Provo, about five times the average.

One has the sense the total might have been higher had it not been for a logistics snag: Says Boardman, "There's no way to baptize right now via the Internet."

Published on April 11, 2014 04:30

Teens Are Leaving Facebook For Facebook

I spent most of last weekend hanging around hundreds of teenage girls who, like me, were trailing around an up-and-coming teen heartthrob who got his big break on social media. I was there for a story, they for selfies, but while we sat cross-legged on the cement floor of a sports arena, they patiently humored my questions about which social networks they use.

Twitter, Vine, Instagram, YouTube, the 13- to 16-year-olds answered. And you guys are all on Facebook, right? I asked my adopted clique, figuring it was such a given, they'd taken their membership there as assumed.

No. Nope. Nuh-uh. Only one girl, in a group of six, had deigned to create an account.

"It’s like the mom and dad version of Instagram and Twitter," a younger girl informed me later.

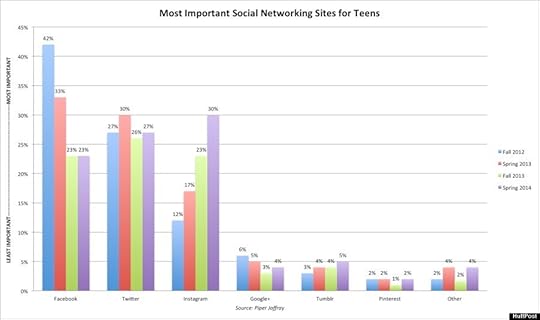

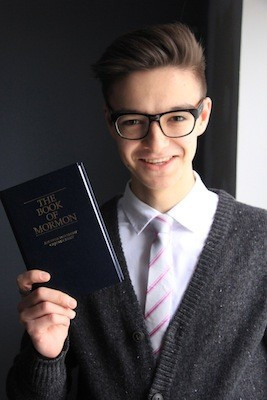

For the first time, teens now consider Instagram the most important social network on the Internet, according to a semi-annual survey conducted by Piper Jaffray. Instagram replaces Twitter, which just last fall surpassed Facebook's place in the top spot. A year and a half ago, nearly half of teens named Facebook their favorite social site.

The results of Piper Jaffray's latest teen survey, which polled 7,500 people, offer some hard numbers through which to trace the fickle allegiances of young people online.

As the chart below shows, teens may be updating their statuses today, tweeting tomorrow and 'gramming the day after that. The only given? If you've got them now, you'll probably lose them soon.

In less than two years, the share of teens who picked Facebook as the top social media service in their lives has nearly halved from 42 to 23 percent, while Twitter flirted briefly with being their go-to social site before being overtaken by Instagram. Since the fall of 2012, the number of teens who see Instagram as the epicenter of their social lives has more than doubled, from 12 to 30 percent.

This nomadic impulse has had social media sites chasing after teens. And they've actually had some success: What teens have really done over the past two years is leave Facebook for Facebook.

For most of its life, Facebook merely cloned the competition. Yet starting with its acquisition of Instagram in 2012, Facebook has embarked on a unite-and-conquer strategy, seeking to expand its empire and hold on to our time by buying any service on which we socialize. Likewise, Twitter and Yahoo, with services like Vine and Tumblr, respectively, have tried to ensure that when teens ditch them, they'll jump to one of their other offerings. It's the fashion world's model, adapted for tech: Social networks are seasonal, so you'd better have the next trendy offering ready to woo the especially-jumpy -- and especially-engaged -- teen audience.

Twitter, Vine, Instagram, YouTube, the 13- to 16-year-olds answered. And you guys are all on Facebook, right? I asked my adopted clique, figuring it was such a given, they'd taken their membership there as assumed.

No. Nope. Nuh-uh. Only one girl, in a group of six, had deigned to create an account.

"It’s like the mom and dad version of Instagram and Twitter," a younger girl informed me later.

For the first time, teens now consider Instagram the most important social network on the Internet, according to a semi-annual survey conducted by Piper Jaffray. Instagram replaces Twitter, which just last fall surpassed Facebook's place in the top spot. A year and a half ago, nearly half of teens named Facebook their favorite social site.

The results of Piper Jaffray's latest teen survey, which polled 7,500 people, offer some hard numbers through which to trace the fickle allegiances of young people online.

As the chart below shows, teens may be updating their statuses today, tweeting tomorrow and 'gramming the day after that. The only given? If you've got them now, you'll probably lose them soon.

In less than two years, the share of teens who picked Facebook as the top social media service in their lives has nearly halved from 42 to 23 percent, while Twitter flirted briefly with being their go-to social site before being overtaken by Instagram. Since the fall of 2012, the number of teens who see Instagram as the epicenter of their social lives has more than doubled, from 12 to 30 percent.

This nomadic impulse has had social media sites chasing after teens. And they've actually had some success: What teens have really done over the past two years is leave Facebook for Facebook.

For most of its life, Facebook merely cloned the competition. Yet starting with its acquisition of Instagram in 2012, Facebook has embarked on a unite-and-conquer strategy, seeking to expand its empire and hold on to our time by buying any service on which we socialize. Likewise, Twitter and Yahoo, with services like Vine and Tumblr, respectively, have tried to ensure that when teens ditch them, they'll jump to one of their other offerings. It's the fashion world's model, adapted for tech: Social networks are seasonal, so you'd better have the next trendy offering ready to woo the especially-jumpy -- and especially-engaged -- teen audience.

Published on April 11, 2014 04:30

April 9, 2014

Hook Of Mormon: Inside The Church's Online-Only Missionary Army

Ryan Tucker, left, with his fellow missionaries.

Ryan Tucker, left, with his fellow missionaries.Until three years ago, Aubert L’Espérance had no idea who Mormons were or what they believed. All he knew was that he liked messing with them.

To be fair, L’Espérance, then 15, was clueless about most religions. The preppy-chic Québécois had never been to church, grew up agnostic verging on atheist and assumed “Mormon” was just another name for the Amish when he first stumbled on the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints online. He’d been browsing his favorite timewaster -- the Art of Trolling, a website less holy, more holy shit. And there, between funny snapshots of misspelled signs, he discovered a new religion and an addictive pastime: pranking the missionaries manning the official “Chat with a Mormon” homepage.

Hoping to attract converts, the church invites people to come online and message anonymously with missionaries who can answer “whatever questions you may have about any Christian topic.” L’Espérance, like thousands of other Internet trolls, abused it spectacularly, logging on with a fake persona and bombarding the Mormons for hours with nonsense questions.

But then, L’Espérance’s hoaxing gave way to something that surprised even him: a genuine curiosity in a group he says he’d assumed was “just some sort of tribe” living in “really remote parts of the universe.” Less than a year after first fooling around with Mormon missionaries, L’Espérance was baptized. Ryan Tucker, a missionary who helped convert him in the church’s chatroom, hailed it as a journey “from troll to testimony.”

"Those chats were so amazing," says L'Espérance. "Before I even knew much about the church, I really felt its power immediately."

The teenager’s unlikely route to baptism helps explain why the white-haired patriarchs of the Mormon church stunned their followers last summer by lifting a ban barring missionaries from social media.

During a worldwide broadcast in June, the church leaders heralded a new era of redemption through screens. All 84,000 of the church’s missionaries would eventually be able to proselytize over the web using a previously forbidden arsenal of media, including blogs, email, text messages, Skype and even Facebook. Along with their in-person preaching, missionaries can now use social networks to check in on potential converts, or woo new ones with status updates about the Heavenly Father.

“The principles missionaries have always been taught actually just work better online,” says Gideon Burton, a professor at Brigham Young University who has advised the church on its Internet missionary work. “It’s going to be a lot more efficient.”

For Mormons, this about-face on social media was nearly as radical as ending the ban on beer. Until the June announcement, the Internet had been off-limits to missionaries to shield them from “worldly entertainment,” like the Times and Twitter, that could distract them from their religious calling. The missionaries, who can serve from age 18, could go online just once a week, and then only to blog about their faith or email their family. Phone calls home were permitted just twice a year.

The same tools recently eschewed as slippery slopes to temptation have now been sanctioned by the church to convey the most sacred of messages and fulfill one of the holiest of Mormon duties.

In what marks a new phase in the evolution of one of the fastest-growing religions in the world, which has doubled in size since the 90s, the Mormon church is doing for religion what Amazon did for stuff: embracing the web to make shopping for a new faith easy, convenient and accessible 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Despite its conservative reputation, the church has actually been an early adopter of any tech that might deliver baptisms. Just as it did nearly 200 years ago, when the church pioneered mass-market distribution of its Bibles by printing a half-million texts, and a century ago, when it released a feature film on the Book of Mormon, now it is pinning its hopes on the marketing muscle of a technology with even broader reach: the web.

In an age of Internet-enabled instant gratification, the church is betting the demand for instant salvation can’t be far behind.

Missionaries at the Referral Center Mission.

The shift on social media actually began over five years ago, in 2008, with a quiet experiment at the Referral Center Mission in Provo, Utah. The first online-only mission -- and the official headquarters of “Chat with a Mormon” -- launched as a call center-type operation set up to answer basic questions about the church and accommodate injured or disabled missionaries who’d have difficulty marching through neighborhoods. Believing that accepting a new faith would be far too profound a revelation for mere chatrooms, the church instructed the inaugural Internet missionary to funnel potential converts to local missions, which could take over offline.

Wrong move, they discovered. People like L’Espérance preferred the safety of a screenname to the awkwardness of lectures from two strangers in suits.

Even within a church legendary for adding converts with machine-like efficiency, the Internet-only mission has been an outlier. Whereas traditional Mormon missionaries convert, on average, six people during their 18- to 20-month service, the online apostles in Provo have averaged around 30 converts per missionary per year, says Burton. And these people stick around. Ninety-five percent of the Internet converts have kept active, a retention rate more than triple the norm.

“It’s unheard of,” says Burton. “[The Referral Center Mission] was equal to the highest-baptizing missions that are out there.”

Damning influences be damned: Church leaders realized these so-called “Facebook missionaries” were getting results too impressive to ignore.

Tracting, or sending missionaries house to house, has since the 1830s been a pillar of the church’s expansion that helped it grow to over 15 million members. In the past few decades, however, the number of converts has shown a concerning drop, from a peak of 331,000 a year in 1990 to just a little over 272,000 in 2012, according to official church records. Sometime between the car phone and the iPhone 5, people stopped opening their doors to the itinerant pairs of neatly dressed proselytizers. Plunging missionaries into the very epicenter of worldly entertainment looks like the best shot at fixing a problem that otherwise may only grow worse.

A recent "Chat With a Mormon" discussion.

“Now, many people are involved in the busyness of their lives. They hurry here and there, and they are often less willing to allow complete strangers to enter their homes, uninvited, to share a message of the restored gospel,” lamented Elder L. Tom Perry, a 91-year-old member of the church’s top leadership body, when he introduced the digital strategy. “Their main point of contact with others, even with close friends, is often via the Internet. The very nature of missionary work, therefore, must change if the Lord is to accomplish His work.”

This e-proselytizing not only marks a change in the machinery of the church, but also suggests a rewiring of our own instincts. As the Mormon church has learned in the course of its experiment, we’d rather discuss life’s most intimate topics through the impersonal anonymity of the screen.

“[W]e could knock on their door and they’d never let us in,” says Emilee Cluff, a missionary who served between 2011 and 2012, of her efforts to proselytize. “But they’d accept our friend request on Facebook all the time.”

Members of the Mormon church believe they’ve been blessed with the “gift of tongues,” an uncanny talent for languages that allows them to preach the Gospel anywhere, to anyone. Tucker, a square-jawed 21-year-old from Syracuse, Utah, will tell you he used this gift to be a more effective missionary. Only, in his case, his “tongue” was the language of email, texting and instant messaging.

Between June 2011 and July 2013, Tucker served at the Referral Center Mission, joining the ranks of dozens of other college-age men who’ve been tapped for the church’s online-only service. He received little initial training -- "they just turned the missionaries loose,” says Burton -- and Tucker had to continually improvise a strategy for making himself and his faith seem friendly through the sometimes sterile medium of typed messages.

Tucker at a cubicle at the Referral Center Mission.

The youngest of six children in a devout Mormon household, Tucker, who has muscular dystrophy, had been looking forward to his mission for as long as he could remember. And yet when he received his call to serve in Provo, he was devastated. The church’s forays into online evangelism were then still largely unknown beyond the innermost circle of the church elite. From what Tucker could glean, he figured he would be put to work filling orders for copies of the Book of Mormon.

But after the mandatory two weeks of missionary training, Tucker realized he’d be counseling more people each day than most missionaries meet in a week, chatting privately online with potential converts as far off as Albania and Ghana for 11 hours a day, six days at a stretch. Tucker would set up Skype- or Facebook-based appointments to tutor prospects in the key principles of his faith. (The church requires these “investigators,” as they are known, to be taught four lessons covering such topics as “the plan of salvation” before they can be baptized.) Most of the time, however, he was juggling two, three or even five chats at a time with anyone who signed on to “Chat with a Mormon.” He’d answer questions about polygamy, take abuse from argumentative atheists and tell people about going to church.

“At the end of most days,” he says, “the number one feeling was exhaustion.”

In the lulls between chats, Tucker used his Facebook profile and personal blog to post digital breadcrumbs like Bible verses or church videos that might lead people his way. (“How did you see the Lord's hand in your life recently? This is a legitimate question -- I want answers!”) The church discourages online tracting -- approaching people at random with messages about the Gospel -- so while Tucker’s friends were trudging through neighborhoods searching for sympathetic ears, the missionaries in Provo just had to sit back and wait for people to come to them.

Which they did, in droves.

Of the thousand-odd strangers who log on to “Chat with a Mormon” each day, slightly more than half have a genuine interest in learning more about the religion, according to missionaries who have served in Provo. This leads to more baptizing with less effort: Missionaries can now put their legwork aside and focus on reeling in a self-selected cohort curious enough to reach out directly. What’s more, the Facebook missionaries also get an all-access pass into neighborhoods their traditional counterparts have struggled to touch.

“This kind of reversed the entire arrangement with how missionaries work: Rather than us knocking on peoples' doors, they were knocking on our door,” says Burton. “People are much more reachable who would otherwise be out of reach -- people in gated communities, remote areas or areas of the world where the church is not allowed to proselytize. We’ve had converts in Asia and other places where the church is not formally recognized, but where people have found the church online.”

“Chat with a Mormon” asks only for a first name, and the anonymity has emboldened people of all ages to sign on for reasons both spiritual and sacrilegious. Chatters come to find, mock, scold, convert, question and berate the missionaries, as well as to confess sins, air doubts and seek advice. A missionary who served in Provo recalls messaging with people so lonely, they sat through weeks of the missionaries’ lessons, only to return, under a different name, hoping to be taught again "because it gave them someone who cared about them." Even though the pseudonyms attract Bart Simpson-esque trolls, they also bring people who can indulge a vague interest in the church without the headache or embarrassment of inviting gangly teenagers into their living rooms. The online missionaries have also tapped into a hidden constituency: members of the church who experience crises of faith that they’re too ashamed of taking up with their fellow believers.

"I think one of the best things about the chat is the anonymity a person has," says Tyson Boardman, the first-ever Internet missionary. "They're able to be completely open with us about any questions they might have reservations asking a person at church. Because of that, we were able to get down to a lot of people's primary concerns."

A survey of people converted by the Internet evangelists found that 60 percent "preferred having online discussions during the conversion process," according a 2010 story in LDS Living magazine. One college-age convert used "Chat with a Mormon" to ask questions anonymously and ensure her Mormon friends weren’t twisting their answers to tell her what they thought she wanted to hear. Michael Johnston, a 20-year-old from Oklahoma who was baptized in 2010 after chatting with Referral Center missionaries, liked the safety of knowing he could quickly exit the chat any time he got uncomfortable.

“On the Internet, if something were to happen, I could just blame it on an Internet error or say, 'Oh, my computer crashed.' I didn’t necessarily have to fully commit to talking with them,” says Johnston. “If I hadn’t had Mormon.org, I don’t feel like I would even be a member of the church.”

One of Ryan Tucker's Facebook status updates, posted during his mission.

From 11 a.m. through 10 p.m., Tucker worked side-by-side with anywhere from five to 30 other young men in a utilitarian room with the industrial carpeting, low ceilings, fluorescent lights and gray cubicles of a car dealership. (Female missionaries also field chats in Provo, though none serve full-time there.)

Tucker and his partner took chats in tandem and would monitor each other’s screens for any illicit tweeting or Poking. Slip-ups do happen, even among the saintly. A “sister” who served in a California mission -- one of a handful that tested the combination of traditional tracting and online follow-ups that will soon be standard -- says a few young men were caught using Facebook to flirt with girls they’d met on their neighborhood rounds. It’s known as the “flirt to convert,” and, though the peccadillo pre-dates social media, it’ll get missionaries kicked off their Facebook accounts.

Since the online missionaries operate a click away from sin at all times, Tucker and his fellow proselytizers had to put up with extra chaperoning by Referral Center Mission staffers who reviewed each message going in and out of the Provo office.

This was “a point of frustration for us because we always felt like we were watched,” says Tucker. He remembers being chastised for sympathizing with a skeptic to whom Tucker had admitted he had personally struggled with the same point of dogma before coming to accept it.

“One of the leaders came back and said, ‘I don’t think it’s good to say you’ve questioned a point of doctrine,’” Tucker says. “I personally think it makes us more reliable to say we’re not just uncritically accepting this, and that we are thinking through this.”

“Chat with a Mormon” missionaries don’t stick to a set script, but do quickly steer conversations toward the virtues of their faith. A pair of proselytizers will begin with low-pressure banter -- they introduce themselves, ask the visitor if she has a question -- then try to use her query to initiate a chat about her beliefs. "My companion is typing up a response," a missionary might say. "But while you wait, why don't you tell me what brought you to Mormon.org?" As they go, they’ll test chatters’ sincerity and try to weed out the trolls by giving “micro-commitments,” such as an article to read. If someone can’t be bothered to click the link, the missionaries assume she isn’t serious and politely wrap up the chat.

Tucker also obsessively analyzed the snippets of text onscreen for clues about each visitor’s receptivity to the Word. He says with help from his "gift of tongues," he could tell if something was amiss just by a subtle switch in punctuation -- from exclamation marks to ellipses -- or by the length of time it took for a chatted reply. He and other missionaries found smiley face emoticons, paired with references to “peace,” “comfort” and “enlightenment,” were good hints their pupils had been moved by the Holy Spirit, meaning they believed the teachings about the Gospel to be true.

“It became fairly easy to recognize people who were less than serious. The hard part was not treating them as such,” says Tucker. “The second we say, ‘This person’s a troll,’ is the second that we give up on helping them.”

Missionaries at the Referral Center Mission.

This person’s a troll, Tucker figured when he first spoke with L’Espérance.

It was the fall of 2011 when L’Espérance, then 16, logged on to “Chat with a Mormon” and, by chance, was paired with Tucker in a chatroom. It was eight months after the peak of L’Espérance’s trolling, and L’Espérance confessed to Tucker that he’d messed around with the missionaries before. Still, he insisted he was back now to learn about their faith. For real.

L’Espérance’s older brother was then recovering from a near-fatal car crash, and L’Espérance, who’d replaced pranks with prayers in the wake of the accident, had sworn to no particular god or faith that he would join a church if his brother pulled through. Now he felt he owed it to the missionaries to at least hear them out after all the hours he’d harassed them.

Tucker, not entirely convinced, shrugged off L’Espérance with a vague suggestion to read the Book of Mormon. To Tucker’s surprise, L’Espérance actually did. The next time the Canadian returned to Mormon.org, the two scheduled a time for L’Espérance’s first lesson on Skype. Each chat session opened with a prayer, then Tucker would guide L'Espérance through the tenants of his faith using church websites, online Prezi slideshows and short, church-approved YouTube videos. Tucker might dive into the intricacies of church history or explain the Mormon take on "the character of God." Every part of the conversion process -- save attending church and entering the baptismal waters -- could elapse over instant messaging.

L’Espérance saw immediate benefits to confining any and all conversion talk to his computer. For one thing, he didn’t have to involve his parents, agnostics who looked askance at religion. After L’Espérance ordered a copy of the Book of Mormon, he discovered with some dismay that it came with a pair of missionaries who showed up at his doorstep one evening.

L’Espérance refused to invite them in, worrying it would disturb his family. So instead, the shivering missionaries spent 30 minutes huddled with L’Espérance on the porch of his house, narrating the life of Joseph Smith Jr. in the chill of the November night.

“If you could possibly imagine the worst circumstances for a missionary lesson, those would be the circumstances,” recalls L’Espérance.

Yet on the Internet, Tucker was never an inconvenience. L’Espérance could message the missionary any time he saw Tucker’s screenname pop up on Skype and the two would have daily, informal chats, even between their official lessons, undisturbed by disapproving parents, intrusive siblings or the need for formality. Missionaries in turn see such talks as a chance to forge stronger bonds with their acolytes and prove Mormons aren't “robots” -- a concern expressed by more than a few missionaries.

“We understood our job was to teach him, yeah, but also to be his friend and help him,” says Tucker.

A Prezi presentation Tucker shared with potential converts online.

With missionaries in the U.K., Mexico and New Zealand now helping man the "Chat with a Mormon" service, anyone can instantly reach a missionary whenever the urge strikes, and in a two-dimensional format many already know and love. The church can even take advantage of people's "rabbit hole" indulgence online -- a tendency to get lost in an endless progression of sites and Google searches that crop up when someone explores a random topic that catches their fancy. Liza Morong, for example, went online one evening after seeing the irreverent "Book of Mormon" musical. The 21-year-old visited Mormon.org, purely to "see just how insane they were," she wrote later. She impulsively signed on to “Chat with a Mormon” to "destroy everything those missionaries were 'told' to believe," but ended up sending a Facebook friend request to the missionary she talked to, then casually messaging about his faith. Three months later, Morong was baptized.

Even after L’Espérance received his parents’ blessing to invite the two missionaries into their home, he still saved the more delicate topics about the Mormon church for Skype. He especially welcomed the privacy of the screen when it came to one of the church’s most challenging commandments, and one nearest to the hearts of 16-year-old boys: the law of chastity, which forbids masturbation, sex before marriage and same-sex intercourse.

“To be very blunt: You don’t really want to discuss things like masturbation with people you don’t know, in person,” says L’Espérance. “It’s a little bit hard looking someone in the eyes and telling them you have problems living the commandments with regard to chastity. And in another regard, it’s a little bit tough talking about those things out loud when your family is around.”

“It was easier online because you don't need to actually speak certain things,” L’Espérance adds. “It’s more of an impersonal thing when you're online.”

More impersonal, but more honest. The two missionaries who’d been teaching L’Espérance offline were the first to learn that he’d decided to convert. But L’Espérance turned to Tucker for help with the full-on crisis that followed L’Espérance’s baptism that December. “Overwhelmed with horrible feelings” about his decision to convert, L’Espérance debated expunging his name from church records just moments after taking his vow. He rushed home, where he says he “cried my life out,” masturbated and refused to speak to anyone.

"I felt like I needed to reject everything that I’d received," he says.

In an earlier age, L’Espérance might never have addressed his doubts and slowly faded away from the church, like the 70 percent of all converts who fail to stay active after their baptisms. Instead, L'Espérance logged on to Skype to share his breakdown with Tucker, who said he was sorry and told L’Espérance to pray. The new convert followed Tucker’s advice. He says he later felt “an overwhelming sense of peace” about his decision.

Today, L’Espérance’s entire Facebook persona seems to have become a tribute to his faith. The church actively encourages its members to engage in their own, informal Internet missionary work by using social media to talk about their beliefs to their friends.

"Your fingers have been trained to text and tweet to accelerate and advance the work of the Lord -- not just to communicate quickly with your friends,” David A. Bednar, a member of the church's second-highest governing body, said in 2011. “The skills and aptitude evident among many young people today are a preparation to contribute to the work of salvation.”

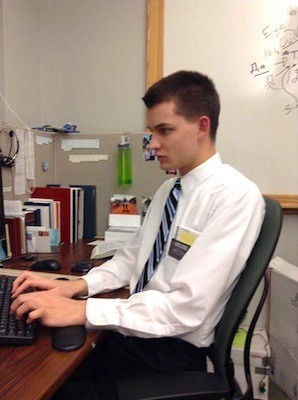

On Facebook, a beaming photo of L’Espérance -- Book of Mormon in hand -- sits over a string of posts about “God’s power” and “brethren in testimony.” His online nickname is “AubertBelieves.” And this spring, L’Espérance will be fulfilling his God-given responsibility to spread the Word as he sets out on his own mission.

L'Espérance's Facebook profile photo.

In July of last year, as Tucker’s mission was coming to an end, L’Espérance decided to fly from Quebec to Salt Lake City to surprise Tucker on the very first day he came home from his service. The two had never met in person, but it seemed to L’Espérance that a deep bond had grown over the months they’d spent messaging about intimate topics and his deepest doubts. Tucker had learned the most personal things about L’Espérance, and had guided him to the most important decision in L’Espérance’s life. If they could be so close over the Internet, imagine the kindred spirits they’d be when they finally met in real life.

After his 8 1/2-hour flight from Canada and two nights in Salt Lake, L’Espérance went to the church where he knew Tucker would be speaking at a Sacrament meeting. L’Espérance went up to introduce himself as soon as Tucker finished his talk. The reunion wasn’t quite what L’Espérance had hoped for.

“I expected him to react more strongly, but it was like, ‘Oh, it’s cool you’re here,’” L’Espérance says, laughing dismissively. “Obviously he was excited about coming home, but I don’t think he understood everything that my presence implied -- my coming over, and all the planning and the scheduling. That’s cool, you know. That’s not his approach.”

Real life may have brought them face-to-face, but in that moment it lacked the intimacy of the Internet, with its seamless harmony and easy honesty. The gathering of people paled next to the merging of pixels.

.articleBody div.feature-section, .entry div.feature-section{width:55%;margin-left:auto;margin-right:auto;} .articleBody span.feature-dropcap, .entry span.feature-dropcap{float:left;font-size:72px;line-height:59px;padding-top:4px;padding-right:8px;padding-left:3px;} div.feature-caption{font-size:90%;margin-top:0px;}

Published on April 09, 2014 04:34

April 2, 2014

How To Clone Amazon When Your Shoppers Don't Have Addresses Or Credit Cards

SINGAPORE -- A few months ago, managers of the online shopping site Lazada, many of whom once paced the gilded halls of firms like McKinsey and J.P. Morgan, found themselves grappling with a predicament: Their warehouse in Jakarta was haunted.

Spooked by a spirit they called the "White Lady," workers there refused to come in for their shifts until the ghost’s inappropriate workplace behavior had been addressed.

So the Lazada team did what most C-suiters do when faced with an intractable HR dilemma, and hired an outside consultant. More specifically, they called a local shaman to exorcise the ghost.

"It's part of the story about us getting used to local customs," explains Lazada's 35-year-old chief executive Maximilian Bittner, who came to the startup world by way of McKinsey, Morgan Stanley and the Kellogg School of Management. Lazada, which he founded, celebrated its second anniversary last month.

Bittner didn’t personally handle the White Lady, but he's had plenty more cultural quandaries to manage as the site works to spread online shopping through five countries in Southeast Asia, an area where Lazada estimates 99 percent of all transactions still happen offline. There was the unexpected flood of orders over the month-long Ramadan holiday that forced Bittner to pull all-nighters at a warehouse packing boxes. Or, in keeping with the country’s custom, the Feng Shui master hired to ensure “good energy” at the Lazada office in Vietnam.

Billed as the Amazon.com of Southeast Asia, Lazada was launched by Rocket Internet, a German startup incubator notorious for cloning Silicon Valley hits in countries where the original Zappos or Airbnb has yet to launch.

Though Lazada might have started as an Amazon replica -- down to it website's color scheme -- the company has had to invent new features and protocols in its push to get Malaysians, Vietnamese, Indonesians, Filippinos and Thai hooked on buying fridges and face wash online. (Lazada will launch this spring in Singapore, as well.) This might come as a shock to the Menlo Park disruptors decrying Rocket’s conquer-with-copies approach, but it seems even the clones can be creative.

What Lazada is up against would be total system overload for any startup CEO shipping stuff around the United States. The company regularly delivers to people who don’t have addresses -- "they write on the checkout, 'drop the package two doors down from the 7-Eleven,'" says Bittner. They ship to islands, like Papua, that have only a single flight ferrying goods each week. They buy from suppliers who still track their inventory with paper and pen. And they’re selling to people who don’t necessarily use credit cards, or even banks. Lazada lets any buyer pay when their package arrives, and over 90 percent of orders in Vietnam are purchased in cash. That poses its own problems, such as figuring out how to be certain a shopper is serious about paying for the item they’ve ordered and will have the money for it when it arrives.

"There are not three issues we have to work on, there are 300 things we need to do," says Bittner, a Munich native who, at 6-foot-4, calls to mind a blonde-haired, blue-eyed Paul Bunyan.

A screenshot of Amazon.com's homepage, before a 2011 redesign.

The homepage of Lazada's site in the Philippines.

Lazada has taken heat for following the Rocket formula of populating its executive ranks with young expats from brand-name consulting and financial firms. It's "extractive colonialism," says Wong Meng Weng, an entrepreneur who runs Singapore’s Joyful Frog Digital Incubator. As Wong sees it, Rocket businesses like Lazada enter Asia, make money, then export it back to the motherland, rather than reinvesting in local startups and entrepreneurs.

Bittner counters that 95 percent of Lazada’s 1,700 employees are from Southeast Asia, and that several employees have already left to launch their own startups. The training Lazada offers employees and suppliers, or the investment it's made in shipping and banking, are “not things which come and go with us,” he adds.

"I believe in the growing of the ecosystem," says Bittner.

Buyers believe in it too. Even in remote Papua, Southeast Asia’s shoppers expect nothing less than the seamless online shopping experience they’ve heard so much about. Cancellations soar each additional day it takes the camera or blender to arrive, so Lazada has been scrambling to speed up delivery. It has an army of customer service reps who do hand-holding for local shipping companies -- Malaysia's version of UPS, for example. (Some of these, says Bittner, are “just starting to figure out how to use a computer.”)

In many places, Lazada also has its own delivery fleet zipping around by motorbike. And in the early days before it had secured suppliers, Lazada scrounged together the goods it promised shoppers by relying on its so-called “hunting teams.” Employees would descend on neighborhood stores with wads of cash to buy the goods Lazada didn’t yet have on hand, but had sold through its site.

"And this includes us being chased out of stores because, after a while, they knew who were were obviously. In every country," says Bittner.

Lazada is trying to win over buyers by deftly handling even the most complex orders, and aims never to turn down a sale. The site’s second order ever was for an Acer computer Lazada didn’t own and didn’t know how to deliver. Rather than lose the customer, they sent someone to buy the machine at a nearby shop, contemplated putting it on a plane with an intern and ultimately spent only slightly less than the price of the computer to ship the Acer to Banda Ache.

Since Lazada, like Amazon, aims to have the cheapest wares, this kind of dubiously profitable arrangement begs the question: Why bother?

Because, Bittner explains, the Amazon model has been shown to work. If Lazada can win hearts and minds now, Bittner believes it can reap big profits as a growing number of Southeast Asians log online, earn higher wages and start expecting the convenience of getting sheets and towels delivered to their door. Investors have plunged $433 million into Lazada, betting Bittner is right. Though he declines to share sales, he says Lazada's five sites are getting close to a million visitors a day.

"The beauty of our business model is, if we check those boxes -- if we provide people the ability to shop, if we provide people the ability to get product to them in a reasonable amount of time -- then they will come," says Bittner.

"Why do I have the best job, or why does she have the best job?" he adds, gesturing at a Lazada managing director. "We get to do real shit. Real fun shit. It’s a lot of fun to figure out a business model which has worked everywhere in the world. And there's no reason why it shouldn't work here."

Spooked by a spirit they called the "White Lady," workers there refused to come in for their shifts until the ghost’s inappropriate workplace behavior had been addressed.

So the Lazada team did what most C-suiters do when faced with an intractable HR dilemma, and hired an outside consultant. More specifically, they called a local shaman to exorcise the ghost.

"It's part of the story about us getting used to local customs," explains Lazada's 35-year-old chief executive Maximilian Bittner, who came to the startup world by way of McKinsey, Morgan Stanley and the Kellogg School of Management. Lazada, which he founded, celebrated its second anniversary last month.

Bittner didn’t personally handle the White Lady, but he's had plenty more cultural quandaries to manage as the site works to spread online shopping through five countries in Southeast Asia, an area where Lazada estimates 99 percent of all transactions still happen offline. There was the unexpected flood of orders over the month-long Ramadan holiday that forced Bittner to pull all-nighters at a warehouse packing boxes. Or, in keeping with the country’s custom, the Feng Shui master hired to ensure “good energy” at the Lazada office in Vietnam.

Billed as the Amazon.com of Southeast Asia, Lazada was launched by Rocket Internet, a German startup incubator notorious for cloning Silicon Valley hits in countries where the original Zappos or Airbnb has yet to launch.

Though Lazada might have started as an Amazon replica -- down to it website's color scheme -- the company has had to invent new features and protocols in its push to get Malaysians, Vietnamese, Indonesians, Filippinos and Thai hooked on buying fridges and face wash online. (Lazada will launch this spring in Singapore, as well.) This might come as a shock to the Menlo Park disruptors decrying Rocket’s conquer-with-copies approach, but it seems even the clones can be creative.

What Lazada is up against would be total system overload for any startup CEO shipping stuff around the United States. The company regularly delivers to people who don’t have addresses -- "they write on the checkout, 'drop the package two doors down from the 7-Eleven,'" says Bittner. They ship to islands, like Papua, that have only a single flight ferrying goods each week. They buy from suppliers who still track their inventory with paper and pen. And they’re selling to people who don’t necessarily use credit cards, or even banks. Lazada lets any buyer pay when their package arrives, and over 90 percent of orders in Vietnam are purchased in cash. That poses its own problems, such as figuring out how to be certain a shopper is serious about paying for the item they’ve ordered and will have the money for it when it arrives.

"There are not three issues we have to work on, there are 300 things we need to do," says Bittner, a Munich native who, at 6-foot-4, calls to mind a blonde-haired, blue-eyed Paul Bunyan.

A screenshot of Amazon.com's homepage, before a 2011 redesign.

The homepage of Lazada's site in the Philippines.

Lazada has taken heat for following the Rocket formula of populating its executive ranks with young expats from brand-name consulting and financial firms. It's "extractive colonialism," says Wong Meng Weng, an entrepreneur who runs Singapore’s Joyful Frog Digital Incubator. As Wong sees it, Rocket businesses like Lazada enter Asia, make money, then export it back to the motherland, rather than reinvesting in local startups and entrepreneurs.

Bittner counters that 95 percent of Lazada’s 1,700 employees are from Southeast Asia, and that several employees have already left to launch their own startups. The training Lazada offers employees and suppliers, or the investment it's made in shipping and banking, are “not things which come and go with us,” he adds.

"I believe in the growing of the ecosystem," says Bittner.

Buyers believe in it too. Even in remote Papua, Southeast Asia’s shoppers expect nothing less than the seamless online shopping experience they’ve heard so much about. Cancellations soar each additional day it takes the camera or blender to arrive, so Lazada has been scrambling to speed up delivery. It has an army of customer service reps who do hand-holding for local shipping companies -- Malaysia's version of UPS, for example. (Some of these, says Bittner, are “just starting to figure out how to use a computer.”)

In many places, Lazada also has its own delivery fleet zipping around by motorbike. And in the early days before it had secured suppliers, Lazada scrounged together the goods it promised shoppers by relying on its so-called “hunting teams.” Employees would descend on neighborhood stores with wads of cash to buy the goods Lazada didn’t yet have on hand, but had sold through its site.

"And this includes us being chased out of stores because, after a while, they knew who were were obviously. In every country," says Bittner.

Lazada is trying to win over buyers by deftly handling even the most complex orders, and aims never to turn down a sale. The site’s second order ever was for an Acer computer Lazada didn’t own and didn’t know how to deliver. Rather than lose the customer, they sent someone to buy the machine at a nearby shop, contemplated putting it on a plane with an intern and ultimately spent only slightly less than the price of the computer to ship the Acer to Banda Ache.

Since Lazada, like Amazon, aims to have the cheapest wares, this kind of dubiously profitable arrangement begs the question: Why bother?

Because, Bittner explains, the Amazon model has been shown to work. If Lazada can win hearts and minds now, Bittner believes it can reap big profits as a growing number of Southeast Asians log online, earn higher wages and start expecting the convenience of getting sheets and towels delivered to their door. Investors have plunged $433 million into Lazada, betting Bittner is right. Though he declines to share sales, he says Lazada's five sites are getting close to a million visitors a day.

"The beauty of our business model is, if we check those boxes -- if we provide people the ability to shop, if we provide people the ability to get product to them in a reasonable amount of time -- then they will come," says Bittner.

"Why do I have the best job, or why does she have the best job?" he adds, gesturing at a Lazada managing director. "We get to do real shit. Real fun shit. It’s a lot of fun to figure out a business model which has worked everywhere in the world. And there's no reason why it shouldn't work here."

Published on April 02, 2014 12:05

March 27, 2014

Going Wild On The World's Most Expensive Instrument

Stradivari's "MacDonald" viola, poised to make history as the most expensive instrument in the world, has three bodyguards and its own white-gloved handler. But David Aaron Carpenter was going just a little crazy on it.

For an informal recital Monday at the Manhattan headquarters of Sotheby's, which is handling the viola's multi-million-dollar auction later this spring, Carpenter, an acclaimed violist, had chosen to play Isaac Albéniz's 1892 "Asturias." The piece is fast and intense, with passages that sound like nothing so much as heavy-metal shredding. It's more modern than most of the music the 300-year-old MacDonald must have encountered during its lifetime. Which is just what Carpenter was after.

"Of course you can play Bach on it. But you can also play a more contemporary work and have an instrument so old and unique make it sound incredible," Carpenter explained later. (Hear him play it in the video above.) "I wanted to showcase this instrument for what the viola could be. The fact that it's been sleeping in a vault for about 30 years -- I just wanted to wake it up and give it a voice."

Carpenter’s fingers danced across the neck of the viola, one of just 10 in existence made by the master craftsman Antonio Stradivari, and one of two that date from the peak of Stradivari's career. (By comparison, Stradivari made some 600 violins). Of the two remaining violas from Stradivari's "Golden Period," one belongs to the Russian government, which has failed to preserve the viola's fine exterior. The other is the so-called "MacDonald" viola, which will fetch at least $45 million, almost three times the price of the world's next most expensive instrument, when it goes on sale later this year.

The MacDonald is said to be in impeccable condition -- "it's as if Stradivari handed it to you from his workshop," Carpenter observed. But after being kept in a safe for several decades, the sleeping beauty will need several years to develop its voice. Carpenter predicts its sound will only improve with time: Even in the five days since he first picked it up, he said, he's heard the viola "[open] up tremendously."

"This week, it has been a joy to get to understand it," Carpenter said. "And even though has an incredible sound at a moment, it has so much more potential than what it is."

Lesser fiddles tend to have a more muscular and muted sound, or develop a less pleasing voice over time, said Carpenter. What distinguishes the MacDonald is the "very sonorous," "very vibrant" quality of its melodies, as well as its ability to project a clear, strong song.

The MacDonald has been owned by a marquis, a duke, a baron and, most recently, the violist of the Amadeus Quartet, Peter Schidlof. He called the viola "utter perfection" in an interview shortly before his death.

One clumsy step during Carpenter's performance earlier this week, and the historic MacDonald could have been just that -- history. Yet the violist insists he wasn't nervous cradling the equivalent of 375 college tuitions under his chin.

Really? Are you sure? Not even a little bit?

No. It feels "like an extension of your body," Carpenter said.

"It's the pinnacle of my career," he added. "Every moment up until this point has prepared me to get to this moment and show the world what an instrument of this caliber can really do."

For an informal recital Monday at the Manhattan headquarters of Sotheby's, which is handling the viola's multi-million-dollar auction later this spring, Carpenter, an acclaimed violist, had chosen to play Isaac Albéniz's 1892 "Asturias." The piece is fast and intense, with passages that sound like nothing so much as heavy-metal shredding. It's more modern than most of the music the 300-year-old MacDonald must have encountered during its lifetime. Which is just what Carpenter was after.

"Of course you can play Bach on it. But you can also play a more contemporary work and have an instrument so old and unique make it sound incredible," Carpenter explained later. (Hear him play it in the video above.) "I wanted to showcase this instrument for what the viola could be. The fact that it's been sleeping in a vault for about 30 years -- I just wanted to wake it up and give it a voice."

Carpenter’s fingers danced across the neck of the viola, one of just 10 in existence made by the master craftsman Antonio Stradivari, and one of two that date from the peak of Stradivari's career. (By comparison, Stradivari made some 600 violins). Of the two remaining violas from Stradivari's "Golden Period," one belongs to the Russian government, which has failed to preserve the viola's fine exterior. The other is the so-called "MacDonald" viola, which will fetch at least $45 million, almost three times the price of the world's next most expensive instrument, when it goes on sale later this year.

The MacDonald is said to be in impeccable condition -- "it's as if Stradivari handed it to you from his workshop," Carpenter observed. But after being kept in a safe for several decades, the sleeping beauty will need several years to develop its voice. Carpenter predicts its sound will only improve with time: Even in the five days since he first picked it up, he said, he's heard the viola "[open] up tremendously."

"This week, it has been a joy to get to understand it," Carpenter said. "And even though has an incredible sound at a moment, it has so much more potential than what it is."

Lesser fiddles tend to have a more muscular and muted sound, or develop a less pleasing voice over time, said Carpenter. What distinguishes the MacDonald is the "very sonorous," "very vibrant" quality of its melodies, as well as its ability to project a clear, strong song.

The MacDonald has been owned by a marquis, a duke, a baron and, most recently, the violist of the Amadeus Quartet, Peter Schidlof. He called the viola "utter perfection" in an interview shortly before his death.

One clumsy step during Carpenter's performance earlier this week, and the historic MacDonald could have been just that -- history. Yet the violist insists he wasn't nervous cradling the equivalent of 375 college tuitions under his chin.

Really? Are you sure? Not even a little bit?

No. It feels "like an extension of your body," Carpenter said.

"It's the pinnacle of my career," he added. "Every moment up until this point has prepared me to get to this moment and show the world what an instrument of this caliber can really do."

Published on March 27, 2014 11:59

March 25, 2014

Facebook Begins Its Quest To Replace Reality

Now, logging onto Facebook means looking at photos of a friend’s birthday party. With Facebook’s latest acquisition, it soon might mean joining the party itself. Or at least feeling as if you’re doing so.

Imagine you slip on a pair of goggles, fire up Facebook and immediately have the sense you’re stepping into someone’s home. When you turn your head left, you see your friend's living room and a half-dozen people leaning against his couch. Take a few steps forward and you’re staring at champagne glasses in the kitchen, listening to Daft Punk pound over the din of cocktail party chatter. At the end of the night, your skin tingles with pleasure as you enjoy a passionate kiss with your date. Yet back in the real world, there's still no one around you.

It may sound futuristic, but Facebook’s new deal signals nothing short of Steven Spielberg-level ambitions. With its acquisition of virtual-reality headset creator Oculus VR, Facebook suggests that it hopes to make reality obsolete -- that the social network is looking ahead to a future in which face-to-face communication is indistinguishable from Facebook-to-Facebook communication.

Facebook announced Tuesday that it would pay $2 billion for Oculus VR, a two-year-old, Irvine, Calif.-based company that has developed a virtual-reality headset meant to give video game players the most realistic possible experience of digital worlds. Slipping on the Oculus Rift headset “provides a truly immersive experience that allows you to step inside your favorite game and explore new worlds like never before,” wrote Engadget in a recent review.

While Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said the first step will be to help Oculus VR develop as a platform, his ambitions for the technology extend far beyond that to mimicking real-life experiences -- from giving people the impression they’re looking at chalkboards in a classroom to simulating the sense they're in a thundering stadium at a live sports event.

“After games, we're going to make Oculus a platform for many other experiences. Imagine enjoying a court side seat at a game, studying in a classroom of students and teachers all over the world or consulting with a doctor face-to-face -- just by putting on goggles in your home,” wrote Zuckerberg in a post on Facebook. “This is really a new communication platform. By feeling truly present, you can share unbounded spaces and experiences with the people in your life. Imagine sharing not just moments with your friends online, but entire experiences and adventures.”

Zuckerberg already sees the simulacrum universe created by Oculus VR as a convincing stand-in for real-world interactions.

“The incredible thing about the technology is that you feel like you're actually present in another place with other people,” he wrote. “People who try it say it's different from anything they've ever experienced in their lives.”

Of course there also has to be gold in them virtual hills to warrant Oculus VR's 10-figure price tag. Oculus could make money for Facebook through the sale of its headset and Rift-specific games. But a more natural route for Facebook, which has never produced its own hardware, would be to sell ads in its lifelike world. Picture Budweiser cans -- paid for by the beer maker -- popping up in your virtual party. Or sponsored Pottery Barn furniture replacing your friends' retro chaise. At the very least brands like Zara or Hyatt might create immersive worlds for Rift-wearers to explore.

Though the Oculus acquisition came as a surprise to many, it’s not so far in a sense from Zuckerberg’s original vision of his social network: Facebook began on college campuses as an online abstraction of offline relationships. People connected with friends and classmates, not strangers. They used real names, not pseudonyms.

With virtual reality and the Oculus Rift, Facebook is continuing the push to move the "real" world onto the Internet. And there's no telling where that stops. Instead of mirroring our offline interactions, Facebook's next move could be to replace them entirely.

Imagine you slip on a pair of goggles, fire up Facebook and immediately have the sense you’re stepping into someone’s home. When you turn your head left, you see your friend's living room and a half-dozen people leaning against his couch. Take a few steps forward and you’re staring at champagne glasses in the kitchen, listening to Daft Punk pound over the din of cocktail party chatter. At the end of the night, your skin tingles with pleasure as you enjoy a passionate kiss with your date. Yet back in the real world, there's still no one around you.

It may sound futuristic, but Facebook’s new deal signals nothing short of Steven Spielberg-level ambitions. With its acquisition of virtual-reality headset creator Oculus VR, Facebook suggests that it hopes to make reality obsolete -- that the social network is looking ahead to a future in which face-to-face communication is indistinguishable from Facebook-to-Facebook communication.

Facebook announced Tuesday that it would pay $2 billion for Oculus VR, a two-year-old, Irvine, Calif.-based company that has developed a virtual-reality headset meant to give video game players the most realistic possible experience of digital worlds. Slipping on the Oculus Rift headset “provides a truly immersive experience that allows you to step inside your favorite game and explore new worlds like never before,” wrote Engadget in a recent review.

While Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg said the first step will be to help Oculus VR develop as a platform, his ambitions for the technology extend far beyond that to mimicking real-life experiences -- from giving people the impression they’re looking at chalkboards in a classroom to simulating the sense they're in a thundering stadium at a live sports event.