Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 31

October 24, 2011

The best of Dracula

The Halloween season here means one thing, one name: Dracula. It's time for my annual re-read of the novel, and to break out the Dracula DVDs. Because I love them all: Schreck, Lugosi, Lee, Langella, Jourdan, Palance, Kinski, Butler, even misfires like Oldman. So I thought it would be fun to pick my favorites specific aspects of Dracula cinema. For the sake of structure, I'm limiting this list to movies that adapt, however loosely, Stoker's actual novel (which rules out Dracula's Daughter, one of my favorites, as well as Love at First Bite).

Leave a comment for a chance to win a signed copy of one of my own contribution to the vampire genre, Blood Groove. Contest runs through midnight Halloween night.

Dracula crumbles to dust.

FAVORITE DRACULA DEATH: That goes to 1958′s Horror of Dracula. Peter Cushing's Van Helsing drives Christopher Lee into a beam of sunlight, where he crumbles to dust before our eyes. The effects are crude and done mainly with editing, but somehow that doesn't matter because the images themselves are so strong, and the actors perform with such gusto.

[image error]

Transylvania, Herzog style.

FAVORITE VERSION OF TRANSYLVANIA: The one in Werner Herzog's 1979 version of Nosferatu. He shot on location as close to Transylvania as you could get in the Coucescu era, and used real Gypsies for the inn scene. The scenery is gorgeous, the people look authentic, and you feel like you're in another country, one that's primal and connected with things the rest of the world has forgotten.

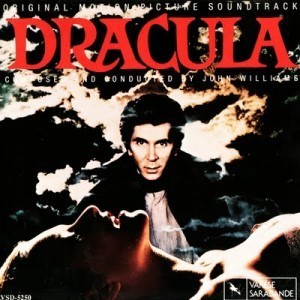

The soundtrack album featuring John Williams' score.

FAVORITE SCORE FOR A DRACULA FILM: This is the second-toughest choice, because there are three strong contenders. Popul Vuh's score for Herzog's Nosferatu is a kind of anti-horror score: all mood and atmosphere, with no bombast at all. John Williams scored Frank Langella's Dracula back when he was still young and hungry, so it has sweep, punch and a catchy central motif. Finally, there's Wojciech Kilar's score for Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula, which is all foreboding, pulsing orchestral percussion. I suppose if I had to pick only one to listen to, it would have be the Williams score. It's the only one permanently on my iPod.

The brides hanker for some Harker.

FAVORITE BRIDES OF DRACULA: The three lovely minxes in the 1974 Dan Curtis/Jack Palance TV version. Jonathan Harker has snuck into the Count's cavernous private study; he looks away, then looks back and boom, there they are, standing still and silent, watching from the far side of the room. When they finally lunge for him, the use of a wide-angle lens makes them seem to cover the distance with unnatural speed, and their hissing, snarling mouths are in total contrast to their previous impassive silence. The only movie where I've actually found the brides scary.

The happiest guy in Transylvania.

FAVORITE RENFIELD: In this case, the first is the best. Dwight Frye's grinning, over-the-top madman in the 1931 Bela Lugosi film is the gold standard against which all other Renfields are measured. All you have to do is imitate his laugh and everyone knows exactly who you mean. Arte Johnson mimicked it perfectly in Love at First Bite.

[image error]

You don't want to cross him.

FAVORITE VAN HELSING: Peter Cushing, hands down. The definitive vampire hunter, starting in Horror of Dracula and going through to The Satanic Rites of Dracula in 1974. High point: Brides of Dracula, which doesn't actually have Dracula in it, but does give Cushing his best moments as Van Helsing.

Someday I shall return as Nixon.

FAVORITE DRACULA: The toughest choice of all, except that it's not, really. If I use the gauge of which Dracula I watch the most, it has to be Frank Langella. Sure, he's got seventies blow-dried hair in what appears to be 1910, but no other Dracula has the presence to play so many scenes in barely a whisper. The big budget means impressive effects and strong casting (Laurence freakin' Olivier plays Van Helsing, even), but the Coppola version had that and for me it withers with each viewing. This film actually grows stronger with time.

October 18, 2011

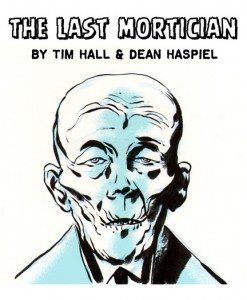

Interview: Tim Hall, writer of The Last Mortician

Cover: The Last Mortician

Recently Tor.com premiered The Last Mortician, a comic written by my friend Tim Hall (author of Half Empty; see my review here) and illustrated by Dean Haspiel. You can learn more about its creation in this video, but I wanted to ask Tim some specific things about the story, which will involve spoilers. So we'll wait while you go read the comic and watch the video. Then come back here for the Q&A.

Done? Okay.

Me: On page 5, the figure speaking against immortality is identified as a religious leader (and bears more than a passing physical resemblance to Billy Graham). He also comes out against immortality after he's achieved it himself. Is he sincere?

Tim: I think he's about as sincere as any of these Elmer Gantry-type religious grifters can be: i.e., "morality for thee but not for me." Hypocrisy is an essential feature of such men, not a bug. You also have to realize that almost all such preachers really and truly believe that women are chattel, just reproductive slaves who are the property of their husbands because that's what the bible tells them. So it's perfectly keeping with his personality that he would believe he needs to stick around to "lead the flock," while making sure enough mortal women are around to keep pumping out children…perhaps only men will be allowed the treatment eventually.

When I first read it, page 10 really jumped out at me. Conventional wisdom says that old people–politicians, dictators, war profiteers–start wars, yet here you have a character say, "It was always the younger generation starting wars." Was that a deliberate inversion, and if so, what does it mean in context?

Tim Hall

It was deliberate. And I love that Dean drew a somewhat Rachel Maddow-esque newscritter giving the reply, spreading the hypocrisy around equally, as it deserves to be.

But really, that's the kind of thing we're always hearing, every day, from every major news network: when trillions are transferred to the wealthy through bailouts and tax cuts, it's called "injecting liquidity"; when they take a tiny fraction of that money and save hundreds of thousands of manufacturing jobs, it's called "socialism." When financial crimes are paid for with draconian, monstrous assaults against the lower classes, it's calmly called "austerity". When those same lower classes get fed up and protest, like they are now, it's "class warfare." The Great Wise Men And Women always find some Other to blame; I suspect absolutely no difference would occur, were the situation of The Last Mortician to come true.

Why doesn't the mortician kill himself–fear or courage?

I remember a great scene in a Charles Bukowski story. He and another man are talking about a mutual friend, who put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger but the gun jammed. Bukowski asks something like, "Why didn't he try a second time?" and the other man says, "It takes guts just to try it once." On page 11 the mortician thinks, "I said I never would…one more mistake won't matter." He's referring to his decision to kill himself, which goes against all his principles and an implied promise he made to his wife to carry on the best he could. I personally believe that life is always the right choice, so I'm going to say it's courage.

Thanks to Tim for taking time to answer my questions. Again, check out The Last Mortician on Tor.com.

October 10, 2011

Interview: Anne K. Black, director and co-screenwriter of "Dawn of the Dragonslayer."

Last week I reviewed the film Dawn of the Dragonslayer, a fun independent fantasy film. This week, I spoke to director/co-screenwriter Anne K. Black about some of the decisions behind the film.

Director Anne K. Black on set.

Me: What sparked the original story idea, and how did the script develop?

Anne: This project began with an assignment to write a fantasy script that was low budget and included a dragon(!). We wrote an initial script for about six months and when it was finished, realized it was way too big. We ended up scrapping it and wrote Paladin [the original title] in just over a month. The scope was small and a coming of age seemed appropriate.

The scenery is spectacular; even the supposedly run-down castle is visually striking. How did the setting influence the script?

When we first arrived in Ireland the castle we'd originally planned on using was, unbeknownst to us, surrounded by suburban neighborhood! We scrambled to find a new place and, through nothing short of a miracle, found Fauddaun Castle. It is one of the prettiest places I've ever been. We changed the script to suit the castle, and moved quite a few scenes to that setting. The sea cliffs in the third act were another location treasure. The third act used to be in several additional locations but we consolidate because the cliffs were just so dramatic.

Your cast is mostly unknowns (to me, at least), but they're uniformly good, and they fit effortlessly into the period setting. How hard was it finding that sort of actor?

We were so lucky to find our actors. We posted auditions on the Internet and thousands of people sent audition tapes. You know instantly when you've seen someone special–their voice, their eyes, the way they react to the lines they are hearing. Our actors were all tremendously hard working and all of them, without exception have beautiful voices–which, I believe, in turn, gives them a charisma and watchability.

How did the final design for the dragon develop?

The dragon's "money shot."

The dragon, the dragon, the dragon. That thing was a lot of work! Wow! We used pre-Raphaelite paintings as a design source on this film. The result is a look which is not strictly period, but rather a romanticized version of the medieval period…that means there are quite a few, although controlled, anachronistic elements. Because of this, it seemed appropriate to have the dragon look more like a fairy tale beast rather than a viable living reptile.

Thanks to Anne and producer/co-writer Kynan Griffin for taking time out from their current project The Virgin and the Warrior to arrange this interview. You can find out more about Dawn of the Dragonslayer at its Facebook page here.

October 8, 2011

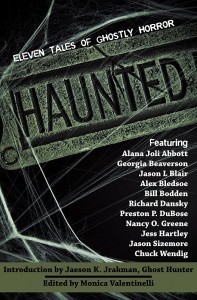

Announcing Haunted: 11 Tales of ghostly horror

"Haunted" anthology–just in time for Halloween!

A few weeks ago I promised an announcement for fans of Blood Groove, my first novel about vampires in Memphis in the Seventies. Here it is.

Sir Francis Colby, the Victorian spiritualist and the only man to ever defeat vampire Baron Rudolfo Zginski, returns in a new adventure, "What's the Frequency, Francis?" as part of the anthology Haunted: 11 Tales of Ghostly Horror, now available from Flames Rising Press.

The other contributors include my friends Alana Joli Abbott, Bill Bodden, Georgia Beaverson and Jason Blair. The book also features an introduction from actual ghost hunter Jaeson K. Jrakman.

October 5, 2011

Guest blog: SJ Tucker on the magick of music

S.J. "Sooj" Tucker's official bio states she performs with "a unique alternative-rock style, flavored with a dose of blues, a dash of celtic, a taste of punk, and even a hint of folk for good measure. Her music is interwoven with mythic lore, avant-garde poetry, and modern storytelling." Having seen her perform, I'll sign that. She was kind enough to write a piece on what music means to her. Find out more about her here.

SJ Tucker

I think of music as my native spiritual and verbal language, more than just about any other form of communication. I truly believe that music can move mountains, heal hearts, and open minds, when it is properly focused. As a performer, a witch, and a healer, I consider music a magickal tool- a magickal partner, even.

Rewind to 2003. One afternoon on my way to a recording session, I had a major spiritual and musical epiphany. I was recording my first full-length album at the time, at a studio near my home in Memphis, Tennessee. As I drove from the office (my then day job) to the studio (my dream job), I listened to NPR. The "Earth & Sky" segment began, and I heard the reporter describe new data from NASA and scientists in Cambridge about a black hole in the Perseus Cluster of galaxies: using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, they had measured the frequency of the soundwaves coming from this black hole and discovered that the waves register a pitch.

That pitch is B-flat.

Specifically, it's B-flat fifty-seven octaves below middle-C.

I wasn't used to scientists speaking my language.

I was so excited that I nearly ran off the road.

Here's a link to the corresponding article.

At this news my head was full of fireworks, connections being made, and joy run rampant. "Music really is part of everything," I thought. "Black holes, clover patches, highways, me: everything in the universe, made up of atoms, has a vibration, and therefore registers a pitch. Music really IS part of everything!"

When I sing, I believe I'm tapping into the source–the divine, Spirit, Universe, whatever you'd like to call it. On Facebook, the "religion" field on my profile reads "musician."

At the Starwood festival in New York a few years ago, I attended a talk on String Theory, where I learned, among other things, that music and the history of the models of atoms that we are all familiar with from school have been linked for years and years. Many articles about the history of our awareness of the atom compare particles to vibrations on a violin string.

The gentleman who gave the talk put it all in these terms: Atomic models tells us that the whole universe is singing, while String Theory tells us that the whole universe is a song.

I came out of that workshop with my mind in a whirl. I wandered back to camp and sat with my friend Jason Cohen, lead singer of Boston-based tribal rock band Incus. He asked me what was on my mind, so I told him about the talk I'd just attended. "I don't know whether I'm a Pagan or a physicist anymore, right now," I said.

Jason put things into beautiful perspective just moments later when he responded by saying, "You know what? As long as you keep singing, I don't really give a rat's ass."

This, it turned out, was exactly what I needed to hear.

I have always sought to give healing with my music, to use my powers for good, as it were. There's a reason that lullabies work, that you can hear a song in a language you do not speak and still be moved by it.

If the documentary The Singing Revolution is to be believed, and I think it is, the nation of Estonia would not exist today if its people had not held onto their folk music traditions so very fiercely, all the way through World War II and the Cold War.

We use music all the time in small ways, to lift our mood, to make our day better, to offset powerful emotions. When I go onstage, I am aware that the audience has put itself into my care- mentally, emotionally, magickally, and spiritually.

My listeners are volunteering to go on a journey with me. At just about every concert of mine, there is at least one person who experiences an epiphany, a bit of healing, or just comes out of the concert recharged and feeling better. Many of them share their stories with me afterward. I wouldn't have it any other way. There is no more powerful proof than this for me, that I am doing my job well.

In the One Giant Leap documentary, which is both very world-conscious and very deeply tied in with the music it contains, Kurt Vonnegut says "Music is proof to me of the existence of God. It is so extraordinarily full of magic."

I concur.

October 4, 2011

Film review: "Dawn of the Dragonslayer"

First, a digression: the SyFy Channel, much like MTV before it, has done considerable damage to the very thing it first embraced. Now the phrase, "A SyFy Original Movie" elicits the same sort of laughter as Mystery Science Theatre 3000, and for the same reason: you hear it and you know you're in for a bad movie. And SyFy is content with that: after all, if audiences are laughing, that means they're watching. So we now have an entire subgenre, the SyFy movie, with casts either culled from past cult shows or featuring newcomers with the talent of an infomercial audience plant; the same generic Eastern European scenery represents everything from Tennessee to Sherwood Forest; and the scripts…well, they're as bad as my first drafts (which is pretty bad). And don't even mention the special effects. And this is where most of our low-budget, independent fantasy films now come from.

All this makes Dawn of the Dragonslayer, an indie fantasy film directed by Anne B. Black, that much more extraordinary and interesting. It couldn't have cost much more than most SyFy movies, yet the things that don't depend on money–talent, the desire to do good work, and belief in the project at hand–nudge it into the realm of real cinema. It's low budget, but not low rent.

The story begins when Will Shepherd, a…shepherd, leaves home after a dragon kills his father. He seeks to serve as bondsman to Lord Sterling, with the aim of being elevated to knighthood. Sterling's holdings have been devastated by the plague, and only he, his daughter and a few worthless servants remain. Will and Kate Sterling fall in love, a union threatened by class distinctions, a vile rival knight and the reappearance of the dragon.

Kate (Nicole Posener) and Will (Richard McWilliams)

To be fair, there's a certain dourness to the film that prevents it from being as much fun as it might. But it gets so many other things right, especially compared to what's normally found in indie fantasy films, that it's easy to overlook this. The film was shot on the west coast of Ireland, and thus has an unexpected scenic beauty. The acting, especially from leads Richard McWilliams and Nicola Posener, is solid and at times inspired. Further, while both are attractive, they also look suited to the story's time and place (no pouty false lips on her, no gym-rat abs on him). The lack of scale–a cast of less than a dozen and virtually a single setting–is used to the story's advantage, not as something to be ignored with a cynical wink and nudge. And Panu Aaltio's music is lush and romantic.

I did a lot of research on dragons for my own dragon novel, Burn Me Deadly, so I appreciate them when they're well-done and get probably too annoyed for my own good when they're bad. This dragon, for the most part, is pretty good. Most importantly it seems an organic part of the film's world, visible through the mist in the distance or just behind the clouds, blending in or flitting out of sight. At the climax we get our first good look at it, and while it's a little over-designed, it never loses that sense of belonging to this time and place. There's a brilliant shot of it lying dead* on the rocks, waves crashing around it.

The dragon itself.

My only real criticism is the dearth of humor. Will is a serious young hero, and the film takes its cue from him; a lighter touch might've made the film move faster. And I must say I prefer the original title, Paladin, to its rather generic replacement.

Still, from the first epic shot of Ireland's coast to the final romantic image, it's clear that real love and attention was put into Dawn of the Dragonslayer. There's a film here bigger than its budget, and I hope it finds an audience.

Watch for an interview with director Anne B. Black and producer Kynan Griffin, appearing here soon.

*Come on, that's not a spoiler; the film has Dragonslayer in the title and you expect a dragon not to be slain?

October 3, 2011

Jennifer Goree: the voice of the Tufa

If the Tufa have a voice, it belongs to Jennifer Goree.

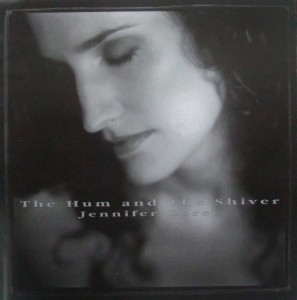

The Tufa may be the fictional people at the heart of my novel The Hum and the Shiver, but Jennifer is very real. She's a singer-songwriter from Six Mile, SC who has recorded three marvelous CDs that demonstrate such a range, it's hard to believe the same person is behind them all. You can hear samples of her current work here.

The cover of Jennifer Goree's first CD.

I first ran across Jennifer about ten years ago. After attending the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, TN, I'd decided to write a novel set in Appalachia, and to base it around the Tufa, an isolated ethnic group inspired by the Melungeons of East Tennessee. I wanted music to be a big part of the story, because the historical folk music of that area influences popular culture to this day. I listened to the classics, going all the way back to the Alan Lomax field recordings. But I also wanted to know about the contemporary stuff, the music being produced by Appalachian musicians now. I wanted, in other words, to hear the modern Appalachian soul. So on a whim, I Googled the term, "Appalachian soul."

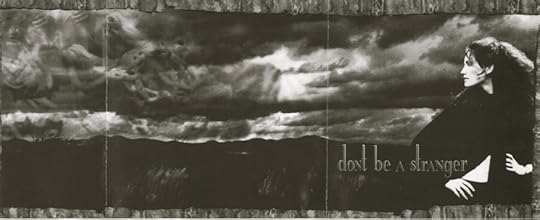

I found Jennifer Goree and the band formed for her second album Don't Be a Stranger: Appalachian Soul.

We corresponded a bit, and I ordered both her then-current album as well as her first one, Jennifer Goree. I knew I'd made a crucial connection when I realized the insert fold-out of Don't Be a Stranger featured an image that could have been plucked straight from my ideas of the Tufa:

The cover insert for Jennifer Goree's second CD.

As I worked on my manuscript over the following months, Jennifer put out a third CD. It was a total change from the first two: smoother, more electronic and heavily produced, yet still filled with her brilliant songs and voice. And the title, both of the CD and its first song, jumped right out at me. I bet you can guess what it was.

The cover for Jennifer Goree's third CD

I loved the implied dichotomy in the words The Hum and the Shiver. I loved the metaphor, which could represent many things. And it fit perfectly with the story I was already developing, about a rebellious Tufa girl who has to find a way to satisfy both her people, and herself.

I asked Jennifer's permission to use the title, and to my eternal gratitude she agreed. Because of that, and because I hear her voice when I imagine the music of the Tufa, my novel The Hum and the Shiver is dedicated to her.

September 30, 2011

Guest blog: Dale Short on the music of the South

Dale Short is the author of Turbo's Very Short Life and The Shining Shining Path, and the host of "Music from Home," which airs on Oldies 101.5 in Jasper, AL and is archived here.

Dale Short

I was born in the middle of the woods near a coal-mining town in northern Alabama, and I grew up in church. Literally.

Seeing as everyone in my family had a role in the small Baptist congregation (deacon, Sunday School teacher, trustee, pianist, song-leader, grass-mower, cemetery committee) I was there every time the doors were open and many times when they weren't. Often, I would spend more waking hours at church than at home, and the line between church members and family members seemed at times nonexistent.

The people were all solid, hard-working, gentle, God-fearing. And together, they would suffocate my heart almost dead. Seeing as these were the days of the Cuban missile crisis, I had regular nightmares that somehow conjoined a nuclear attack and the Second Coming of Christ, happening simultaneously in my back yard.

I say "almost dead" because I escaped. As I would write decades later in an essay, "The day I was old enough to move out, I ran from that narrow world into the welcoming arms of science and reason like a hostage greeting his rescuers."

But, God, did I miss their music.

My mother, grandparents, and a neighbor had a gospel quartet that rehearsed in our living room, and they were in great demand to sing for funerals and homecomings, at our church and many others. My grandfather had a rich, untrained bass voice, and from the day my voice changed he would always nudge me in the pew during congregational hymns and whisper, "Help me sing bass, buddy…" My teenaged self would grimace and sing precisely loud enough to remain unheard by anyone except him.

I had said good riddance to the hellfire and brimstone. But for years afterward, the music ambushed me constantly. From the open doors of city churches as I walked the dogs. From distant radio stations in towns I drove through at night. From vinyl LPs, old and new. Doc Watson. Gram Parsons. Mahalia Jackson. Rosetta Tharpe. The Stanley Brothers.

For me, there are only three types of songs: (1) those I don't care for, (2) those I enjoy listening to, and (3) those that fill me like oxygen and make me laugh and cry at the same time before I even realize what's going on.

What brought this ancient history to my mind was finishing Alex Bledsoe's new novel The Hum and the Shiver, which takes the familiar theme of traditional backwoods Southern music and makes it new and universal as only fine storytelling can do.

I would bet good money that the author sojourned in some dark places of the heart while writing it, but the result pays off with compound interest on the page.

As for my own apocalyptic childhood nightmares, the only way I was finally able to vanquish them was to write a fantasy novel (The Shining Shining Path, 1995) in which the second coming of Christ and a nuclear war take place simultaneously in my grandparents' backyard.

In return for his gift of The Hum and the Shiver, I wish Bledsoe peaceful dreams. And if you're a reader, I envy you the pleasure of reading it for the first time.

September 26, 2011

Reading in public: advice from the pros

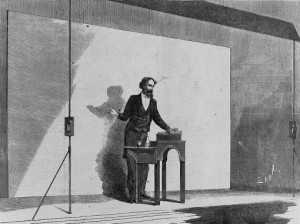

Charles Dickens reading. Bet he followed Kelly Barnhill's mom's advice (see below).

Last Monday I posted a few things I'd learned from doing readings in public. I asked some of my writer friends for their suggestions as well, since many of them have much more experience than I do. Below are their comments. Thanks to all of them for pitching in.

"I have a lot of stage and comedy background, so I'm somewhat in my element when I do a reading of my work. Here's what has worked for me, and might help you.

"First of all, breathe. Take a moment at the podium or microphone. Say something to personalize the event, like, 'Thanks for having me, it's great to be here in the breakroom of the local library.' Humor helps! Set up or introduce the reading if it's not the first chapter, or needs some context. But make sure your setup or introduction is concise. Practice making eye contact with your audience or looking at your audience as you introduce and conclude the reading. It's fine to focus entirely on piece as you read it, but having that connection with the audience at the top will really help you. Take your time. More often than not, when one speaks before an audience, one rushes. So slow down. It will feel like you're going at a glacial pace, but you're not. Practice. Practice the reading so much that you know that piece inside and out. Record yourself and listen to it. Painful, I know. Or do it for friends and/or family so you know what it feels like. If you're going to be doing a lot of readings, and you want to be terrific at it, I suggest an improv, beginning acting, or standup comedy class. It can really develop a lot of confidence. Most of all, have fun. Seriously. Enjoy the work that you created, just like, I presume, you enjoyed it when you wrote it. The people there to hear you will respond to that, trust me."

Mary Jo Pehl, writer and cast member of Mystery Science Theater 3000 and Cinematic Titanic

"Teach yourself to look up as you read. Your audience will appreciate seeing more of you than the top of your head. You don't have to make eye contact with anyone, but you do want to be sure you look toward everyone in the audience."

"The way I do it is, I look down as I reach major punctuation: periods and semicolons. I get the next chunk of text in my head and look up again. (The other method I know of is to look up when you reach major punctuation.) I don't do this constantly throughout the whole reading, but I try not to go more than four or five sentences without looking up."

Sarah Monette, author of The Mirador and Melusine

"Most useful thing I do is read through the section out loud beforehand with a highlighter and mark difficult sentences to remind me to read them slowly and clearly. I also use those same highlighted points as reminders to look up at the audience, because they provide a visual anchor, so I don't lose my place."

Kelly McCullough, author of the Cybermancy series and the upcoming Broken Blade (which I've read and which rocks–AB)

"Read slowly. Twice as slow as you think you should. Never go over your time, it's rude to the audience and the other readers. And watch your audience, make sure you're not boring them to death. Plus I almost always bring a flash piece and do a quick, short reading at the beginning of time to allow for latecomers."

Jay Lake, author of Mainspring

"Relax. You're among friends who want you to do well and be entertaining. No one shows up to an author reading hoping to see a car wreck."

Matt Forbeck, author of Amortals and Vegas Nights

"Don't read for more than 15/20 minutes…for your own sake, as well as that of the audience; Don't be afraid to speak in different voices…the audience may be amused, but that's why they came. Think to yourself…when I wrote this, I wrote it so that I could share my ideas with as many people as possible…now I'm doing it. So don't lose your nerve now. They came to listen to you. Don't let them down. Every author is an actor, too."

Graham Masterton, author of Fire Spirit and Demon's Door

"Pick 2-3 short sections and arrange them so they flow well. It's not unlike stand-up. You have to move swiftly and humorously. Short readings with a q/a always sell more books than a long reading."

Dean Bakopoulos, author of Please Don't Come Back from the Moon and My American Unhappiness.

And finally, perhaps the most practical advice of all, courtesy of Kelly Barnhill's mom:

"Arrive early, chat up the staff, charm the pants off 'em, (well, not literally), and buy a sh*tload of books so they appreciate you and ask you back. And pee before you read (That was my mom's go-to advice for pretty much anything)."

Kelly Barnhill, author of The Mostly True Story of Jack

September 22, 2011

Stone Reader: One and done

The DVD cover for "Stone Reader"

Because I'm so far from the cutting edge that I'm likely to fall off the spine (that's the flat part of the blade opposite the edge), I just now saw 2002′s documentary Stone Reader. It's a must-see for every writer, and especially for writers who wonder if anyone "gets" what they're doing. This is the story of how a writer and reader connect.

It's set up as a mystery. Mark Moskowitz tried reading The Stones of Summer when it first came out in 1972, after seeing a rave review in the New York Times. He found it impenetrable. Twenty-five years later he tried it again on a whim, and thought it a masterpiece. But when he sought more books by the author, Dow Mossman, he found not only were there none, but that the author himself had vanished from the literary scene. He was, like Margaret Mitchell or Harper Lee, a writer who was "one and done," but without the benefit of their subsequent status.

Since this film was made when the internet was in its infancy, it was used only as a tangential tool for tracking down Mossman. Instead Moskowitz relies on letters, phone calls and personal visits, trying to find anyone who remembered the book or Mossman. Along the way he meets some interesting people, but every lead peters out, until…well, if he'd utterly failed, there wouldn't be a movie, would there?

The destination is compelling, but the journey is also worth the effort. The movie probes the connection between writers and readers, writers and their muse, and why someone can spend years producing a monumental book and then simply stop writing. Moskowitz is a self-satisfied presence as narrator and onscreen guide, and I've read some reviews that couldn't get past this. As a writer I found the film incredibly interesting, and was left with a sort of numb sadness at the idea of so many writers putting forth so much effort for so little return.

All of this took place before the digital revolution in publishing, however, and begs the question, would Dow Mossman have vanished so thoroughly if The Stones of Summer had been available as an e-book? Is this yet another way that e-publishing is changing the whole paradigm of writing? I don't have an answer to that (and in the deleted scenes, you realize that neither did the publishing industry in 2002), and honestly, it's only a secondary question. The primary question, for me, remains something still left unanswered by the movie: what drives a man to write like that? And what drives him to stop?

If you've seen the movie, I'd love to hear your thoughts.