Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 29

February 6, 2012

"We two are now more than us two": messing with the rhythm

The American poster.

Every good work of dramatic storytelling has an internal rhythm that we, as readers/watchers/listeners, subconsciously pick up on as we go further into it. It often means we're able to sense where a story is going before we should, based on hints the storyteller didn't even know s/he was giving us. Sometimes it can be obvious, like the ten individual ten-minute takes that comprise Hitchcock's film Rope. Other times it's far more subtle, like the way the ending of Peter Hoeg's novel Smilla's Sense of Snow seems first jarring, and then in restrospect, inevitable.

I was reminded of this when I rewatched one of my favorite films, Wim Wenders 1987 story of angels in love, Wings of Desire. Yes, it was remade into a trite and obvious American film, City of Angels, but we're talking about the original now, a film of startling brilliance and delicate touch (and, I must also add, a totally different ending).

Marion, unaware Damiel is watching.

Succinctly, the plot involves the angel Damiel falling in love with Marion, a trapeze artist in a two-bit circus stuck in West Berlin during the Cold War era. As an angel he's followed her without her knowing it, learned her secret desires and sadness, and at last gives up his heavenly existence for the chance to meet her face to face.

This meeting happens in a Berlin nightclub, where Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds provide a throbbing soundtrack. Marion and Damiel finally meet in the bar, and the scene is set for him to make a speech professing his love for her, which in turn will make her fall for him. It's what we think the whole movie has been building toward.

But instead, she makes the speech to him. With no idea of his history, of who he really is or how long he's watched and adored her.

This is part of what she says:

Damiel and Marion

Now it's serious. At last it's becoming serious. So I've grown older. Was I the only one who wasn't serious? Is it our times that are not serious? I was never lonely neither when I was alone, nor with others. But I would have liked to be alone at last. Loneliness means I'm finally whole. Now I can say it as tonight, I'm at last alone. I must put an end to coincidence. The new moon of decision. I don't know if there's destiny but there's a decision. Decide! We are now the times. Not only the whole town – the whole world is taking part in our decision. We two are now more than us two. We incarnate something. We're representing the people now. And the whole place is full of those who are dreaming the same dream. We are deciding everyone's game. I am ready. Now it's your turn. You hold the game in your hand. Now or never. You need me. You will need me. There's no greater story than ours, that of man and woman. It will be a story of giants… invisible… transposable… a story of new ancestors. Look. My eyes. They are the picture of necessity, of the future of everyone in the place. Last night I dreamt of a stranger… of my man. Only with him could I be alone, open up to him, wholly open, wholly for him. Welcome him wholly into me. Surround him with the labyrinth of shared happiness. I know… it's you.

(You can see the scene on YouTube here.)

Sure the movie is stylized; it implies that Peter Falk, the actual actor and not a character, was once an angel as well. It's loaded with poetic voice-overs, shifts from black-and-white to color, and has a sense of magic in the most mundane places in the world. But this is the moment when it all comes together and creates not just the romantic relationship between the protagonists, but the world view that they inhabit. Just as he secretly watched her, she somehow knows all about him.

David Gerrold, in one of his books describing his work on Star Trek, gave this simple advice for avoiding cliche (I'm paraphrasing): When you find yourself about to write something obvious, do the opposite. It's good advice, and it's what Wenders and his co-writer Peter Handke did. I assume this speech was written by Handke, the poet who contributed most of the monologues. But whoever wrote it, it was the brilliance of giving it to the opposite character from the one you'd expect that makes it resonate. Like the kindness of the angels in the film, the romance shows up where you least expect it.

So in a sense, Wings of Desire ends up exactly where we think it will. But it gets there via a totally unexpected path. It stays true to its rhythm, but at the same time surprises us by turning cliche on its head. And as such, it's an object lesson for all storytellers working in any form.

January 30, 2012

Guest blog: Deborah Blake on maladaptive intertia

Author Deborah Blake

Deborah Blake is the author of six nonfiction books and the paranormal romance Witch Ever Way You Can, as well as the excellent short story "Dead and (Mostly) Gone," found in The Pagan Anthology of Short Fiction, along with my story, "Draw Down." Deborah has been kind enough to write about a condition every author has, or will, experience.

(And catch my guest blog on her site, along with a giveaway, here.)

*****

You've probably heard of "inertia." It is actually a physics term that refers to the fact that a body at rest tends to stay at rest. You probably haven't heard of "maladaptive inertia," however. That's because I made it up. But that doesn't mean it isn't real. In fact, I'm guessing you've suffered from it once or twice, without even knowing it. Allow me to 'splain.

I came up with the term maladaptive inertia years ago to describe the condition when it is just easier to keep doing more-or-less nothing (play one more game of solitaire on the computer, watch just one more show on TV) than it is to make yourself get moving on the things you actually NEED to do. So you waste lots of time and energy that you don't have, and end up with that same old to-do list staring you in the face. Hence the "maladaptive." This is not a time spent resting and rejuvenating, it serves no useful purpose, you know you're doing it and that it isn't good…and yet…there you are. Still sitting on your arse. Maladaptive inertia.

Admittedly, it makes for a good excuse. "Sorry I didn't write that blog post for you, I had maladaptive inertia." "I can't take out the garbage, honey, I have maladaptive inertia." Feel free to borrow it. [As long as you give me credit for coming up with it. I'm going to write a book about it. You know—as soon as I get over my maladaptive inertia.]

For writers, maladaptive inertia can be particularly tough. I had to put aside the novel I'd started in November, to deal with the December rush at my day job (I run an artists' cooperative, so the holiday season is crazy time). Once the rush was over, I intended to jump right back into working on the writing. But I had…you guessed it. The truth is; it is a whole lot easier to KEEP writing than it is to START writing. Or to start up again.

So how do you get over maladaptive inertia, and get back to your writing (or taking out the garbage, or whatever it is you are supposed to be doing that is useful, rewarding, and necessary)?

Here are a couple of the things that work best for me:

Keep plugging away at it. Don't say, "Well, I've tried for three days to get back to my writing (or whatever). It hasn't worked, so I give up." Keep kicking yourself until you JUST DO IT.

Have your friends help you. When I am trying to get back into exercising, a friend and I often call each other up and say, "Okay—I just did 20 minutes. Tag, you're it." There is nothing like a friend to kick your butt into gear when you can't do it on your own.

Set rules and rewards. For instance, when I am trying to get back into the writing zone, I'll tell myself – no Twitter until you've written SOMETHING. Or, you don't get a glass of wine until you've done at least three pages. (I find that one particularly motivating. But you can substitute chocolate, or whatever you like, such as watching your favorite TV show.)

Mostly, I find that it works to just get started on the writing, no matter what it takes. Because once you've started something, it is easier to keep working on it. Remember that other rule of physics: A body in motion is likely to stay in motion.

So put down the remote, walk away from the internet, or do whatever it is you have to do to break your pattern of maladaptive inertia. You can do it! I just wrote five pages. Tag—you're it.

*****

Thanks to Deborah for sharing her insight. You can find out more about her at her website.

January 28, 2012

Interview: Kim Dryden, co-director of Appalachian film "Over Home"

My introduction to Appalachian culture, which figures so strongly in The Hum and the Shiver, really took place in the late 1990s. Prior to that, I'd looked on the Smoky Mountain region of Tennessee with some of the same distant awe as anyone else. Tennessee is a long, narrow state, and I grew up on the whole other end from the mountains. But in 1998, I first attended the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, Tennessee. And it was there that I first encountered the work of Sheila Kay Adams, storyteller and ballad singer.

Storyteller and ballad singer Sheila Kay Adams.

Sheila Kay has spent her life performing, and preserving, the ballads she learned sitting knee-to-knee with family and friends in and around Sodom, NC. In many ways she's the last of her kind. And now filmmakers Kim Dryden and Joe Cornelius have begun work on a film, Over Home: Love Songs from Madison County, chronicling both Sheila Kay's life and the history of ballad singing in general.

Follow this link for a preview of what they have in mind.

Kim Dryden was kind enough to answer some questions about the project.

Me: In this era of instant communication, what for you is the continued value in the ballads and Sheila Kay's way of teaching them?

Kim: The ballads are important for several reasons. I think they are stories that are universally relatable, and therefore appeal to a very broad audience. What's more, while they were originally brought here by Scots-Irish immigrants, I feel they've truly become an important part of the American musical heritage, much like jazz. Because of that, they ought to be protected fiercely, not just by those like Sheila who grew up with them as part of their birthright, but by the general public, including universities, museums, etc., as well. That's part of what we're trying to do, is get down on record, in visual format, what this tradition is all about. Finally, I think the ballads are most important for the way they bring people together. A big part of what our film explores is the idea of balance between the culture that once nurtured the tradition of ballad singing versus the music itself, and asking what is more highly valued in places like Sodom Laurel. It's so interesting to me that although the old time way of living is dying out, ballads are still hanging on, even thriving in some ways. I think this is in part because of people like our characters – Sheila, Saro, and Damien – who not only sing these old songs, but work to give them context, a new community in which they matter.

The way Sheila teaches these ballads, knee-to-knee, is very important to that idea of community building. Being face to face with someone, spending time with them in their homes and in their lives, gives such a deeper meaning. I think this method is more important now than ever in this day of instant communication. It takes a really dedicated person to seek out someone like Sheila and put in the sustained effort over weeks, if not months or years, to learn from her in a meaningful way.

I first encountered Sheila Kay as a storyteller. How do you explore that role in the film?

Kim Dryden setting up to interview Sheila Kay Adams.

I also found Sheila first as a storyteller, through the NC Storyteller's Guild's website. Ballad singing is so much a part of storytelling. We'll explore this idea in our film by using the ballads, with emphasis on the lyrics, as a narrative device to transition and set mood/tone. Sheila is, more than anything, I think, a storyteller, both on stage and off. That's how she communicates with others, and so naturally it'll come across on film as well.

Which ballad speaks most directly to you? (My personal favorites are "Shady Grove" and "Omie Wise.")

My personal favorite is "Pretty Saro." I absolutely love the lyrics, and was so incredibly moved by seeing Cas Wallin sing it on Youtube. It makes me wish I was alive then to see that. I also really like "Over Home," although that's a new one. The lyrics really speak to me, hence the name of our film.

Thanks to Kim for taking the time to talk to me. You can follow the progress of Over Home at the project's Facebook page.

January 23, 2012

Review: Mean Guns (director's cut)

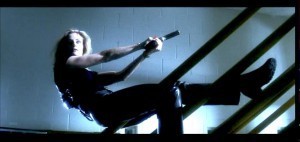

Kimberly Warren as "D."

There's a theory that silent-era filmmakers were just on the verge of perfecting movies as a legitimate art form when sound came in and took away the primacy of the image. Suddenly what people said became just as important, if not more so, than what they did. A purely visual medium entered into an uneasy symbiosis with the spoken word.

Occasionally, though, you run across a film that fully embraces its visualness. Not something like The Artist, which recreates the silent era, but a modern film that nonetheless tells its story in primarily visual terms. The real test is to imagine watching it without hearing the dialogue; if you can still follow the story, then it's awfully close to pure film.

Christopher Lambert as Lou. And an example of the brilliant widescreen photography.

Mean Guns, released in 1997 and starring Christopher Lambert and Ice-T, is just such a movie. Taking advantage of a location (the soon-to-open Los Angeles County Jail), the film has a group of cold-blooded killers brought together, locked in and given the weapons to kill each other. The prize for the last three survivors: a suitcase full of money, and their lives.

The film's first DVD release was a full-screen, pan-and-scan version. I once read that the reason so many modern action scenes are so hard to follow, is that this generation of filmmakers grew up watching full-screen versions of films shot in a widescreen aspect ratio. They internalized the chaos that comes when you chop off half the image, and that's become the new standard. Certainly doing that to Mean Guns both added a level of anarchy the director never intended, and needlessly muddled a story that was crystal clear in its initial execution.

Now director Albert Pyun has released his widescreen cut, and it's a revelation. This is a staggeringly visual movie that takes full advantage of the geometric shapes and reflective surfaces available in the brand-new facility. Further, the film is brilliantly cast with distinctive actors who don't all look alike, a problem in way too many contemporary movies. You're never in doubt who's onscreen, their spatial relationships are clear and the nonstop action scenes breath and pulse with life.

The visual style that's totally lost in the pan-and-scan/fullscreen version.

I was astounded to rewatch this film in its correct aspect ratio and realize that it is, in fact, an action masterpiece. I don't use that term lightly, either; I'd put this on an equal footing with George Miller's The Road Warrior and Walter Hill's The Warriors, two films that could also lose their dialogue tracks and still be completely watchable. This is a movie worth tracking down and diving into.

Oh, and did I mention it's scored with mambo music?

You can get the widescreen version directly from Pyun's production company by e-mailing curnanpictures@gmail.com.

January 16, 2012

The rare ingredient: joy

Eco's latest

Something not mentioned often in reviews of books is the writer's sense of joy.

Writing, whatever you may think, really is hard. Done well, it's as taxing as any other job. You can't just show up and watch the clock. Sure, some books are better than others, and good writers can write bad books, but unless you're James Patterson or someone at that level, you don't have the luxury of just typing something out and sending it off. Everything you do has to be bled, sweated and cried over.

And with a lot of books, you can tell. Many a serious literary novel bears the marks of its writer's angst like battle scars, and those same authors often parade their injuries as proof of their sincerity, like Henry V says the veterans of the Battle of Agincourt will do one day. That plays into the idea of the Tortured Artist, a cliche so insidious and romantic that many beginning writers assume that if they're not miserable, they're doing it wrong.

I work hard at being a writer. I write every day, averaging around a thousand words, and that's in addition to revising, editing and researching. I'm usually reading at least three books, some for fun, most for work. I'm always thinking about writing, often to the detriment of my other activities ("Dad? Dad? DAD!") But even with all this, you know what?

Writing is fun.

Eco's next-to-latest

I was reminded of this when I read, back to back, Umberto Eco's two most recent novels, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana and The Prague Cemetery. Eco wrote one of my favorite novels ever (Foucault's Pendulum), and is probably best known for The Name of the Rose, which became a hit movie with Sean Connery, Christian Slater and F. Murray Abraham. Eco is undoubtedly literary; he's written scores of nonfiction books and essays, and his novels are dense, vastly researched and lacking in any obvious plot structure or characterization tropes. And he writes in Italian, so he has to be translated, the sure sign of something literary.

But I've never read anyone, even through translations, who so thoroughly conveys the joy he feels in writing. In The Prague Cemetery you can practically hear him giggling between the lines as he references historical events and personages in sudden, often pratfallish jokes that contrast with the novel's very serious theme. The central conceit of Foucault's Pendulum is, in fact, a joke gone wrong: the publishers of a vanity press for conspiracy theorists decide, on a whim, to combine all the paranoid ramblings into one grandly unified Conspiracy Theory, then discover that their Frankenstein concept might actually be true.

I hope some of that same joy comes through in my writing. I take it seriously, sure, and deal with some serious things, but I also believe that the experience of reading won't be fun if the experience of writing is totally miserable. I want people to laugh along with my books, to remember them as enjoyable journeys, however serious their ultimate intent. Life is miserable and difficult enough without paying to experience it in prose.

What authors convey their joy to you?

January 9, 2012

A dialogue on the "Common kickass heroine"

Author Teresa Frohock

Recently my friend, author Teresa Frohock, brought to my attention a review of a current urban fantasy/paranormal romance title in which the reviewer referred to the main character as "the common kickass heroine." We were both struck by the implications: that what was once a fresh symbol of female empowerment in the male-heavy world of fantasy had become, through repetition and erosion, a cliche.

Since my most recent novel, The Hum and the Shiver, features a heroine I consider "strong," and Teresa's novel Miserere: An Autumn Tale has both a vivid warrior-priestess heroine and a terrific female villain, we discussed what the "common kickass heroine" might be, and what it means for writers and readers. Teresa, what's your background with strong heroines?

Teresa Frohock: In spite of all the novels I've read over the years, two strong heroines that have always remained me are Vonda McIntyre's Snake from her novel Dreamsnake and Anne McCaffrey's Killashandra from her novel The Crystal Singer. Both characters are portrayed as intelligent and emotionally strong young women who meet their obstacles with resourcefulness and determination. Those were the qualities I wanted for both Rachael and Catarina in Miserere.

This emotional strength was one of the aspects of Bronwyn that I admired so much in The Hum and the Shiver. She is a young woman who took chances and stepped outside the traditional paradigm to become someone with an inner depth that can't be camouflaged with flash and glitter.

What was your basis for Bronwyn's strength in The Hum and the Shiver?

Brownyn is a reaction to all those "Casablanca" endings, where the hero/ine makes some noble sacrifice in the service of some "greater good." I wanted her to decide that yes, I'll accept these responsibilities you've been pressing on me all my life, but on *my* terms. It's the kind of strength that you don't see very often, and has little to do with mundane things like "ass kicking." It's strength of *character.* Rachael in Miserere has that, despite a betrayal that would send most of us to the bottom.

I still feel the template is Ellen Ripley in Aliens. She has no super powers or lethal skills, just a steely determination that exceeds even that of the professional soldiers around her. Alas, once "Buffy" came along, the idea that tiny women must demonstrate their strength by destroying large men/supernatural creatures overwhelmed the concept of strength being a non-physical attribute. Now the Manic Pixie Dream Girl, Ass-kicking Version, is the standard.

Do you think that's because perhaps deep down, both readers and writers can't reconcile the idea of strength with attractiveness?

Teresa's terrific first novel

Yes, and I think part of it is a backlash to earlier tropes. Let's face it: Daphne and Thelma in Scooby-Doo always perpetuated the trope that you can't be both beautiful and intelligent. In high school, I read The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales by Forrest Carter and the character Laura Lee is described as plain. Her hands were too large to hold teacups but perfect for holding a rifle. I related to Laura Lee based on that description, because I knew how she felt. A woman couldn't be strong and beautiful. Now all the female characters are dainty with hands perfect for holding both teacups and assault rifles.

This is obviously how women want to see themselves. Everyone wants to relate to the characters in a story, but there is also a need to see grander pictures of ourselves. These "strong" women want to be seen as sexually attractive/aggressive, but the assault rifle (or Ninja sword or whatever) says: I don't need a man. I can take care of myself.

I'm curious about what guys see in characters like this. Do you see them as empowered women or caricatures?

It's hard to say, because I think I've aged out of the target audience. Certainly younger men, gamers and serious comic book fans, respond to these images. The entire anime industry probably wouldn't exist without them. But for me, yes, they feel like caricatures. The only possible justification for them is that they have supernatural powers, which I think gets us closer to the cliché we began with. All these women shown from the neck down on book covers, displaying their tramp-stamp tattoos as they carry some bladed weapon loosely in their fingers, are the result of trying to "realistically" have it both ways: heroines who are conventionally attractive, yet capable of battling the bad guys.

But what makes this so interesting, to me, is that this stereotype is promulgated by women, for women in the paranormal romance genre. Which leads into the question of, is emulating male sexuality really a sign of liberation, or just more cliché?

I don't think emulating male sexuality is a sign of liberation at all. I find it demeaning to women that we have taken the very aspects of male behavior that women disdain and flipped those male defects into virtues for women. Men who use sex as a weapon are animals, but women who use sex as a weapon are empowered? How did we hit that point? The sexual liberation I remember being discussed by feminists was all about being in control of our bodies and fates in a society that demeaned us all as brainless sluts.

I digress.

From an authorial viewpoint, any character that suffers a lack of emotional growth in the course of the story is in danger of becoming a cliché. I think the "common kick-ass heroine" will eventually go the way of the "Sam Spades". There will always be some novels with those kinds of characters, but they won't be as prevalent. Which makes me wonder what might be the next big thing?

The next big thing is always impossible to predict. I've heard it would zombies, but while they're popular, I can't see a single zombie character becoming a romantic symbol. I've also heard angels would be next, but again, while they're often used, I don't see any becoming the romantic symbol that vampires and werewolves have become.

What do you think?

I'd like to think the next big thing would be … normal men and women. I'm not counting on it though. I'm still trying to get the zombie thing. I'd throw my money on fallen angels. Not because I write them—nobody is going to be flinging themselves on my version of the fallen—but I have seen a lot of bare male chests on cover art along with fallen angel references. Someone is just going to have to come up with the right combination that clicks with the fans, I suppose.

Teresa's novel Miserere: an Autumn Tale is published by Night Shade Books, who also did the hardcover edition of my novel The Sword-Edged Blonde. You can read my review of her book here, and find out more about Miserere, including a free read of the first four chapters, here.

January 2, 2012

Crackerbox Palace: the adult world that never was

George Harrison (l.) and part-time Pythoner Neil Innes (in drag).

If you've read this blog very often, you probably know I grew up in a tiny Tennessee town with little in the way of cultural opportunities. That meant I learned about music from two sources: WHBQ, an AM station in Memphis where you could hear just about anything (alas, now an all-talk sports station), and the more narrowly-formatted Rock 104 from Jackson, one of the FM hard-rock stations that have also vanished.

While reading Julian Dawson's biography of all-star session keyboardist Nicky Hopkins, I was reminded of the music I listened to then, and how distant, urbane and sophisticated it seemed to me at the time. In particular, I found George Harrison's "Crackerbox Palace" going around in my head.

(To hear the song and see the Eric Idle-directed video, you'll have to click on this link. Embedding "disabled by request.")

Because it was by an ex-Beatle, the song went into ongoing rotation at Rock 104, where it shared airtime with "Free Bird," "Kashmir" and "Beth." At the time, I assumed it was rife with hidden drug references, obscure bits of English trivia and sophisticated Anglophile wordplay. Moreover, I imagined that the people who "got" all these hidden meanings were themselves urbane adults who wore black turtlenecks, smoked smoothly rolled joints (I hadn't heard about cocaine yet) and chatted about the latest literary events. I was certain these people actually knew George Harrison personally, and dined at his mansion while listening to his tales of what the song was really about (keep in mind I was a 13-year-old when this song came out). I wanted to be part of this clique someday, and assumed (because as a kid, it all seemed possible) that once my first book was published, it would just happen.

I'm not sure when this particular image of "adulthood" finally faded. Now I recognize the song as ridiculously insubstantial, almost as thin as the solo stuff McCartney was excoriated for back then. I understand the nature of the money-and-drug culture that fueled creative people at that level (though not from personal experience; I'm nowhere near that interesting). And if I were forced to hang out with a bunch of dope-smoking, lit-quoting, turtleneck-wearing Brits today, I'd probably jump out the window.

But at some level, I'm disappointed that adulthood turned out to be what it is. I seldom get a chance to listen to music uninterrupted, certainly very little new music, and nothing on the level of the Beatles, together or apart. I don't do drugs, or drink anything stronger than coffee anymore. I don't hang out with celebrities; occasionally I meet one, but it's never as an equal. I spend most of my time worrying, writing and parenting.

So now that I think about it, maybe my original idea of "adulthood" wasn't so bad after all. Is it too late to go to Crackerbox Palace?

December 30, 2011

Bang Head Here: passive vs active voice

Banged vs. Banging

A Facebook friend, Henry Snider, recently asked me, "Why is it that fewer writers seem to understand the difference between showing versus telling? Passive voice (running my head into a wall)!"

In my case, passive voice–vastly simplified, the use of "-ing" verbs (telling) instead of "-ed" words (showing), such as "I was running" instead of "I ran"–is simply how my brain initially creates sentences. All my first drafts are filled with passive voice, and from talking to other writers that seems to be common. Why we do that is more of a mystery, about which I could find no information in my limited research. Certainly as a species we do most of our actual interpersonal communicating by telling (after all, do we really was to show how someone ran into the wall?).

Those initial passive-voice drafts never see the light of day. In revision all those "-ing" words become "-ed" ones unless there's a good reason to keep them passive. And occasionally there is, because passive voice is not inherently "wrong." It becomes wrong when it interferes with the clarity of your sentence. "I was running" could be a perfectly correct statement, if your character suddenly returned to consciousness after a trauma (say, fighting zombies) and realized, "I was running away before I even knew it." To say "I ran away before I even knew it," misses the moment of blankness for the character in which s/he simply lost awareness of his/her activities.

But to be fair, those times are rare. In most cases the passive voice is detrimental to your clarity, certainly to your sense of pace and energy. So why, as Henry asks, is it so common?

I suspect there are two reasons, both based in the changing nature of publishing.

First, the advent of easy self-publishing means, simply, the editor is no longer a required part of the process. In fact, none of the usual gatekeepers–editors, agents, reviewers–are essential. It's entirely possible for someone to write a book, format it and post it for sale with no outside input at all. When that happens, mistakes–often of the very basic kind–can occur. This is because those gatekeepers serve functions besides deciding who gets in and who's kept out. Most crucially, they provide perspective, something that the writer simply can't bring to the table. When you've lived with a story for the weeks/months/years it's taken to write it, you're too close to see it the way a reader will. An outside perspective can tell you not just when you've used passive voice, but which plot points are unclear, which jokes are unfunny*, and which characters seem unrealistic. This doesn't have to be an editor; it can be a trusted friend who is smart enough to catch these things, and who is willing to be honest with you. But that perspective is crucial, and many writers don't realize it.

Second, and this is based more on anecdotal information that first hand experience, many authors–some of the most successful authors, in fact–are no longer edited with the same rigor they once were. This can be due to the writer's ego, but it's also a result of changes in the publishing industry. A writer such as James Patterson will sell as many books unedited as he will edited, so why waste resources on the process, when those resources–time, expertise, effort–will not affect sales? Whereas an author with a smaller readership (i.e., someone like me) truly benefits from the attention, both critically and economically (a better book = more sales).

Now, many top-selling authors are quite capable of editing the passive voice out of their own manuscripts, and do so. And for those that do not, passive voice might be the least of their problems. But when you find a blatant grammatical error in a best seller, this thought process very well may be the reason.

But that's just my perspective on the issue. What do the rest of you think?

*something my editor excels at, bless him.

December 24, 2011

The best* Christmas Eve gift

All I want for Christmas….

*Sarcasm.

Once about ten or twelve years ago, in the weeks leading up to Christmas, I went through a process that will be instantly familiar to every struggling writer: I sent a query letter to a publisher, and they responded with a request to read the first three chapters of my manuscript.

This happened fairly often, so I did not get my hopes up. Still, I sent along those chapters, and eventually they asked to see the whole manuscript. This was rare, so now I allowed myself to (guardedly) get excited. I sent my manuscript off and waited, fingers crossed, watching the days creep toward Christmas and daring to hope for the best Christmas present I could imagine: acceptance for publication.

I got a form rejection letter. No personalized notes explaining what they didn't like, not even comments like, "Not for us, but please submit again." Just a form letter addressed, as I recall, to "Dear Author."

And that form letter arrived on Christmas Eve.

So to everyone struggling to be a writer out there, I hope 2012 brings you the greatest gift of all: the publication of your book. The only certainty is that you won't be published if you quit trying, so don't give up, and don't lose faith; I was 44 when my first novel came out, and I started writing it when I was seventeen.

What's your worst story about submission and rejection?

December 18, 2011

Wake of the Bloody Angel cover art

For all the fans of Eddie LaCrosse, here's a peek at the cover for his next adventure, Wake of the Bloody Angel. Watch for it summer 2012!

Cover illustration once again by Larry Rostant.