Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 25

August 6, 2012

The Man (or Alien) in the Mirror

I was reading this blog by author Theodora Goss and came across this comment:

“My parents’ generation was raised under communism, and still retains the assumption that literature is important to the extent that it adheres to literary realism.”

Ms. Goss, like me, is a fantasy author. Her works include the novel, The Thorn and the Blossom, and the story collection, In the Forest of Forgetting. Like me, she’s had to struggle with the issue of making the fantastic seem real, and on occasion the real seem fantastic. In broad strokes, that’s what a fantasy author does.

But her comment that her parents believed “literature is important to the extent that it adheres to literary realism” (emphasis mine) struck a note with me, because I believe the same is true of fantasy. And for the writer, that’s even harder.

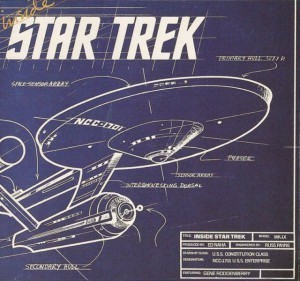

When I was a geeky teen living in west Tennessee, I discovered (thank you, Starlog magazine) the record album Inside Star Trek. This was a mostly spoken-word disc put out in 1976, during the fallow period between the end of the original series and the release of the first film. Gene Roddenberry spoke to Trek then-alums William Shatner and DeForest Kelly about their characters, and Mark Lenard appeared in character as Sarek to discuss the origins of Spock. Roddenberry also spoke to Isaac Asimov, one of the greats of SF. And something Asimov said, part of his advice to aspiring writers, has stuck with me ever since:

When I was a geeky teen living in west Tennessee, I discovered (thank you, Starlog magazine) the record album Inside Star Trek. This was a mostly spoken-word disc put out in 1976, during the fallow period between the end of the original series and the release of the first film. Gene Roddenberry spoke to Trek then-alums William Shatner and DeForest Kelly about their characters, and Mark Lenard appeared in character as Sarek to discuss the origins of Spock. Roddenberry also spoke to Isaac Asimov, one of the greats of SF. And something Asimov said, part of his advice to aspiring writers, has stuck with me ever since:“The writer must use all things human and all things human-made and all things that impinge upon the human being as his raw material.”

There was no mention of technology, or science, or fantasy creatures, or aliens. Just a three-fold reminder that whatever you write has to have a human connection.

The “literary realism” Ms. Goss’s family seeks is inseparable from the Asimovian “all things human.” Which means that SF/F/H writers cannot ignore it, if they want to be relevant, and more than mere escapism.

And then comes the real challenge: we have to make the reader buy into the “literary realism” of a squid from Venus, an elf from Middle Earth, or a vampire from Transylvania (or Memphis). We have to find the “all things human” within a troll, a werewolf, or a faery.

The great writers of “literary realism” hold up a mirror to life, which of course means they are showing us a reflection of ourselves that we immediately recognize, because it looks like us. The great writers of fantasy, science fiction and horror are also holding up a mirror, but one that shows us a version of ourselves that looks nothing like us. Yet if they do it well, if their mirror is true, we’ll see ourselves in it anyway.

Hemingway wrote The Old Man and the Sea. Tolkein wrote, in essence, The Old Man and the Hobbits, Dwarves, Elves and Trolls. Both are classics. And both show us ourselves.

August 1, 2012

Guest blog: author Dale Short on superstition

Dale Short has guest blogged here before, and he’s welcome any time. Between his writing and his radio show, he’s got a full appreciation of all aspects of Southern life, and his collection of short stories, Turbo’s Very Life, is one of the best books I’ve ever read. He’s joining us today to talk a bit about superstitions in the south and how they impact everyday life even now.

Dale Short has guest blogged here before, and he’s welcome any time. Between his writing and his radio show, he’s got a full appreciation of all aspects of Southern life, and his collection of short stories, Turbo’s Very Life, is one of the best books I’ve ever read. He’s joining us today to talk a bit about superstitions in the south and how they impact everyday life even now.

***

Southern Superstitions: Encoded in the Blood?

In the remote North Alabama coal-mining community where I grew up, being superstitious (which nearly all of us were) was like walking a tightrope. This was because the Missionary Baptist Church (to which nearly all of us belonged) totally frowned on what the Bible called “witchcraft and divination.”

And the church interpreted scripture broadly, so as to be on the safe side. Their prohibition against gambling, for instance, meant we weren’t permitted to own playing cards–or dice, including the pair that mysteriously disappeared from the Monopoly set I got for Christmas one year.

As a result, witchcraft and divination didn’t just cover such portals to the beyond as Ouija boards and fortune-tellers, but included horoscopes and Zodiac signs. Yet everybody I knew kept a copy of The Old Farmer’s Almanac in their house or barn because “planting by the signs” was as natural as breathing; everybody who farmed had a tale to tell about some season when they’d ignored the almanac and had meager crops to show for it. The signs also specified the proper time for slaughtering a pig or a cow, and everybody knew of some ill-timed slaughter that had caused the meat to spoil.

Even without such divination devices as almanacs and Ouija boards, though, we seemed to have a complex list of superstitions encoded in our blood, and many of them involved coal mining. It was bad luck for a woman or girl to venture near the mouth of a mine. One variant even said that it was bad luck for a man on his way to work if he chanced to meet a red-haired woman on the road. Mules in the mine who became unaccountably skittish were thought to be seeing ghosts, or “haints,” that humans couldn’t. And so on.

In retrospect, many superstitions seemed to be sexist in motivation, such as “A whistling woman and a crowing hen / Always come to some bad end.” On the other hand, I’ve encountered a number of people over the years who apparently had the power of supernatural healing, and the ability to find lost objects and foretell the future, and all of them were female.

After my grandmother joined the church as a young woman, she openly scoffed at superstition. And yet our family knew that she was the seventh child of a seventh child, supposedly giving her the power to cure the oral infection known as thrush (also known as “the thrash”) that was once common among babies. She remembered, as a child, neighbors bringing their thrash-suffering infants and asking her to blow her breath into their mouths. She was embarrassed by the attention, she told me once, but nonetheless the babies were cured. As a churchgoer, she had managed to mostly convince herself the healings were coincidence.

The superstition that most sent a chill up my back during childhood, though, was birds-and-windows. If a bird tried desperately to break through a window pane, it was said that someone in the family would die soon. I’ll never forget the afternoon I was in the house alone and a redbird flew in a fury against the picture window. The bird hit the glass again and again with increasing force until its head left a smear of blood down the pane as it fell—whether dazed or dead I didn’t know, because I was afraid to go outside and see. I decided not to tell my parents about it later, in some irrational hope that if I never spoke about it, it wouldn’t be real.

Days passed, then weeks, and nobody died. But I had a new and recurrent nightmare, of bird after bird slamming against the windows of our house until the glass was covered with blood.

Not long ago I was searching through old files in my mother’s storage house and found a short story from that period of time that I had forgotten I wrote. It’s not very good. Not even a real story, more of a vignette, about a boy afraid to leave his house because flocks of birds keep attacking the windows, but eventually they stop and nobody dies. The prose style is a shamelessly Capote-esque ripoff.

The tale doesn’t claim any new literary ground, but it occurred to me that while many new nightmares have come and gone in the years since, I have no memory of dreaming about the bird scenario again. Is it superstitious for me to believe that writing fiction is an act of self-exorcism, that can actually clean old horrors out of brain cells and make room for the new?

Probably. But it appears to be a gift from what we call, for lack of a better term, the beyond. And I’ll take it gladly.

July 30, 2012

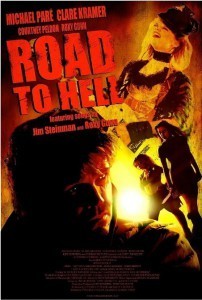

Review: Road to Hell

There are a lot of film parodies, but not so many films that function as commentaries. Offhand, the best known example might be The Freshman, in which Marlon Brando both spoofs his Godfather persona and simultaneously creates a new, ironic character.

Road to Hell, the new film by Albert Pyun, is a commentary film, in a sense. Michael Pare plays Cody, a riff on Tom Cody, the character he played in Walter Hill’s Streets of Fire. There’s also a pair of characters named Ellen, the original of which was played by Diane Lane in the Hill film. And although the film stands on its own, its fannish shout-outs to the earlier film give it a special sort of resonance to fans.

Not that the films are that similar. Streets of Fire was a big-budget flop, a kind of music-video adventure set in a timeless city that was half 1950s, half 1980s. It celebrated innocence: guns were fired but no blood was spilled, punches and kisses were exchanged but no real damage was done by either. Jim Steinman contributed a couple of his trademark overwrought songs. I loved it, and still do, but I can also see why others wouldn’t: it requires a special mind-set to step into that world and accept its stylizations.

Pare (l) and Kramer.

Road to Hell is like the hallucinations of someone with a fever who’d just watched Streets of Fire and perhaps read too many “true crime” novels. Working against a green screen, Pyun creates a surreal desert landscape in which this version of Cody collides with a spree killer (Clare Kramer, with great demented eyes) and her girlfriend (Courtney Peldon). The heart of the movie takes place in and around a broken-down jeep, where violence is ever-present among the three, although you can’t quite be sure how it will manifest. Cody is waiting for one Ellen, but it’s ultimately the other Ellen he finds.

The actors–it’s essentially a four-hander–are uniformly good. Kramer (a Buffy alum) is totally uninhibited, and Peldon is surprisingly subtle as her sort-of accomplice/girlfriend.

But the real surprises are the veteran Pare and the newcomer Roxy Gunn. Pare, whose career as a leading man never quite took off after his debut in Eddie and the Cruisers, shows every mile on his face as this alternate-universe Cody whose skills as a soldier and killer have become his whole life. I’ve always been a fan of Pare’s, one of those actors who does his best even when the whole film is against him, and here he’s subtle and affecting (as well as shockingly brutal). He shifts with ease from being iconic to pathetic and back.

Pare (l) and Gunn.

Gunn, making her debut, is a real find. In a time when all young actresses tend to blur together into one generic face, she really stands out. An actual musician (that’s her singing, her band The Roxy Gunn Project performing, and she wrote some of the songs), she has a natural ease onscreen that makes every moment seem real. In a movie where the main landscape is faces, she has one that conveys everything her character is thinking and feeling.

So I enjoyed Road to Hell for what it is: a riff on a movie both I and the filmmakers clearly loved, filtered through Pyun’s own unique aesthetic (which you can experience in a purer form in his recent Bulletface). I’m glad Pare got a chance to really chew into a part, and Roxy Gunn’s debut is magical. Will the general public like it? I don’t know. But then, it’s not every movie that includes both disembowelings and rock concerts, severed heads and love ballads. If you enjoy this sort of mash-up, done irony-free and with its own agenda, you’ll probably dig it. I sure did.

You can read my earlier interviews with Road to Hell director Albert Pyun here, and screenwriter/producer Cynthia Curnan here. Yes, I’ve been looking forward to this movie for a while.

July 27, 2012

Guest Blog: Michael Underwood on Influences

[image error]Michael Underwood’s debut novel, Geekromancy, has been called “modern, sleek and whip-smart” by Cassie Alexander, and Mari Macusi says it’s “fun, fresh and full of geek culture references that will have you LOLing to the very last page.” I met Michael at WisCon this year, and asked him to share his thoughts about influences and how they affect his writing.

Bringing It with You

I grew up in the land of SF/F. I watched Star Wars and Star Trek as a wee youth and grew up geek without knowing that was what I was doing. So when I set out on my path to be a writer, I naturally brought those experiences with me, and unsurprisingly, I ended up writing genre fiction.

But there’s more to life than swords & lasers. Cultivating a cool list of interests is something I think all writers should do. It means we have several perspectives on the world, get to meet people from outside our ‘home’ communities in fandom, and, in my case, give a writer more things to say in their writing. If everyone has read the same books, seen the same movies, and we’re only ever re-writing those same stories, responding to the same list of shared narratives, then we’re a closed system, entropy will win out, and the community would cease having anything remotely new or interesting to say.

My own passions outside the genre include history, martial arts, social dance, and geek culture. I’ve brought each of those passions into my writing, and will continue to do so in new ways as my passions develop over time.

For my debut novel Geekomancy, I took my life-long love of geekdom and geek cultures and crammed it into every single nook and cranny of the novel. I had my lifetime-so-far of experiences as a geek to draw upon, but I also had a M.A. in Folklore Studies, with a focus in subcultural studies, as well as years of experience working customer service in the world of hobby and leisure retail, not to mention a tenure in the world of food service.

Y’know, like Clerks. Every day that something went terribly wrong at the game store, or someone came into the bookstore asking for ‘That one book. You know. It has a blue cover,’ the story of Clerks resonated more and more with me. I wanted to portray a protagonist who was happy with her world and her friends, if not with her immediate post-breakup circumstances, so I gave her a world of boisterous customers, happy hours, delicious pizza and marvelous milkshakes – my world, as I see it, and as I’ve lived it.

There is no one kind of science fiction story, or even three or ten. There are as many different stories as there are people telling them. The world of genre fiction is just one of many places where conversations about society, the nature of humanity, ethics and morality are playing out. We use lasers and swords, other artists use guns and courtrooms, society balls and immaculate gardens.

Genre is neither beginning nor end, it’s a combination of tools and settings, an ongoing conversation that exists on its own and in dialogue with many other conversations. We’re always adding new inputs, incorporating new information, processing, thinking and re-thinking. And it’s awesome.

Thanks to Michael for dropping by and sharing his thoughts. You can find out more at michaelrunderwood.com.

July 25, 2012

Rant: the Penn State Penalties

I’ve been following the Jerry Sandusky child molestation case since it broke. The Freeh report, which explicitly blamed Sandusky’s continued ability to molest children on the deliberate actions of those in power at Penn State, including legendary football coach Joe Paterno (arguably the most powerful man on campus), led to unprecedented penalties against the university and its football program. And it should: supporting and covering up a child molester, knowingly allowing him a decade’s worth of freedom to continue his vile crimes, deserved the harshest penalties possible.

And yet, there are apologists. There are people who think this punishment is unfair, that it tarnishes Paterno’s “legacy.” To them, I say, wake up: this is Paterno’s legacy.

But the thing that irks me most about their arguments, the thing that most makes me want to slap these people, is this:

It’s a children’s game.

This detail has gotten lost in the minutiae of the Sandusky/Paterno affair, and the Penn State response, but it’s crucial. Football may be played by adults, but it’s a children’s game.

Think about the vast amounts of money given to these men for coaching and playing the same game any eight-year-old plays. Yes, they play it better, but it’s the same game. We support, indulge and overlook horrendous conduct by these people, for playing a damn children’s game well. We’ve destroyed our higher education system, once the envy of the world, by pouring all the university money into a goddamned children’s game.

In the article linked above, Ujas Patel, who heads the Penn State alumni association chapter in London, says the NCAA penalties unfairly target the future of the football program that he described as vital to the university. The fact that a football program is vital to a university, more vital apparently than abused children, shows just how out of whack our cultural priorities have become.

The next time you watch a football game, college or pro, ask yourself how your life changes based on the outcome. Unless you’re part of the economic chain directly connected to it, the answer is: not at all. The winning or losing of a children’s game doesn’t, and shouldn’t, ultimately matter in the real world.

The fact that it does, and the fact that grown men considered it more important than raped children, is something that every coach, player and fan of every sport should think about.

July 23, 2012

By Request: the Music I Grew Up With

After reading The Hum and the Shiver, musician Andrew Brasfield asked me, “What kind of music did you grow up on?” Given that music is such a big part of the Tufa mythology, and that almost every one of my other books has at least some musical element or inspiration, it seemed a valid question.

Being from the rural south, I learned a lot of music at church. I realized just how much, and how embedded it was, when I brought the family back to my little country church for Easter this past year, and didn’t need to reference the hymnal even once during the service. The songs were simple, unquestioning statements of belief, with no room for doubt. At church camp, though, the songs were different: I still remember how spooky it was to sing Larry Norman’s post-Rapture classic “I Wish We’d All Been Ready” sitting around a bonfire, which couldn’t help but put you in mind of hell.

“Only visiting this planet” to remind us we’re all going to HELL!

Then there was the secular stuff, from two main sources: WHBQ AM out of Memphis, and Rock 104 FM out of Jackson. The former was one of those classic radio stations that played everything that was popular regardless of genre: you might actually hear Kenny Rogers, Parliament and Paul McCartney, in that order. We listened to that station in the morning before school (and on the way if you had a portable radio), so it formed a common basis for social interaction. The flip side, so to speak, was Rock 104, which we listened to at night. Here I learned about genuine rock, the heroes (and villains) you never heard on AM pop radio. Which led to the Great Divide: Led Zepplin vs. Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Cover of Led Zeppelin IV, aka “ZOSO,” aka “We’re too stoned to name our album.”

Zeppelin was hard rock, which meant drugs, British men who dressed like women (i.e., 70s-era Robert Plant) and essentially songs you sat slack-jawed and listened to on headphones, possibly while under the influence of illicit substances. Skynyrd were your pals, long-haired to be sure but not effeminate at all. When you listened to them, you wanted to drink beer and do rebel yells (the cliche about requesting “Free Bird” did not arise in a vacuum). It was a divide that you could not straddle*: you were in one camp or the other. I was, proudly and unapologetically, a Skynyrd fan. That meant I could also like Springsteen, Bob Seger, Molly Hatchet and the pre-Michael McDonald Doobie Brothers.

The last true Skynyrd album.

That, then, is the musical foundation of my life. My tastes have broadened significantly since then (some would say softened), and now I’d like to think I can enjoy any good song of any genre. I’ll never again have that same enthusiasm of discovery, though, as I did the first time I heard “That Smell” or “Rosalita.” You only get that once, and that’s only if you’re lucky. Thankfully, I was.

*Now, ironically, both bands are grouped together as “classic rock,” and if the stars align you might hear “Stairway to Heaven” immediately after “Free Bird.”

July 16, 2012

Of eddies, witches and titles

The very manly paperback cover.

It’s no secret that the Eddie LaCrosse novels owe as much to mystery as they do fantasy, especially the hardboiled pulps and films noir of the 30s and 40s. So when I wrote Wake of the Bloody Angel, I knew its title would have to be a play on a title from the mystery genre, much as Burn Me Deadly echoes Kiss Me Deadly.

With that in mind, I turned in the manuscript under the title The Two Eddies, a play on the (unfairly, IMO) much-maligned sequel to Chinatown, The Two Jakes. Not only were there two characters named Eddie (my hero, and the pirate Black Edward Tew), but I liked that the term “eddy” also meant a current of water. My publisher, however, felt the title was too low-key, and that we needed something that would better jump out at a potential reader. I’m no elitist: I understand the purpose of marketing, and I’m generally sympathetic to it. Further, my publisher didn’t say, “We’re changing the title,” they asked me for another title, which is mutually respectful. And, luckily, I had one ready.

There aren’t that many nautical noirs. In film there’s The Phantom Ship, the first film from Britain’s legendary Hammer Studios, based on the Marie Celeste and starring a fading Bela Lugosi. There’s Wreck of the Mary Deare, with a young Charlton Heston and an old Gary Cooper. And there’s The Ghost Ship, part of Val Lewton’s extraordinary series at RKO that also included Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie.

Then there’s Wake of the Red Witch.

John Wayne as Captain Ralls.

Based on a novel by Garland Roark, it was made into a 1949 film starring John Wayne before he became codified as a Western star. He plays a captain who scuttles the titular Red Witch for reasons that go back years, and involve a girl (although she’s not a femme fatale; more of a naif fatale, if that’s a legitimate term). Its flashback structure resembles that of Out of the Past. And it has one of Wayne’s best introductions, when he’s discovered lashed to a piece of wood, drifting among circling sharks, and the film’s villain Sydney rescues him.

SYDNEY: What’s your name?

WAYNE: Ralls.

SYDNEY: Your full name?

WAYNE: Captain Ralls.

There’s nothing in the plot of Wake of the Red Witch that really influenced Wake of the Bloody Angel, but the concept of a wake, like that of an eddy, has a double meaning: both the waves left by a ship’s passage, and a memorial service for someone who’s died. And so, relatively painlessly, The Two Eddies became Wake of the Bloody Angel.

(Trivia: the mechanical octopus used in the film was “borrowed” [i.e., stolen] by Ed Wood’s crew for Bride of the Monster, as depicted in Tim Burton’s exquisite ode to perseverance, Ed Wood.)

July 13, 2012

Interview: Holly McDowell

The first installment of Holly McDowell’s serial novel

I met Holly McDowell at one convention, and heard her read at another. Her novel, King Solomon’s Wives, is a serial e-book produced by Colliquy, with an intriguing premise. The publisher describes it this way:

The two thousand descendants of King Solomon’s ancient harem have the ultimate power of seduction: Their very touch is as addictive as any drug. But that power comes at a price: Wives die giving birth. They can only bear daughters. They are only fertile until the age of twenty-four. Hunted for hundreds of generations by men who crave their touch and fear its power, the Wives have kept safe by following three simple rules:

A Wife shall have no meaningful relationships outside the clan.

A Wife’s addictive touch may be used only for procreation or to protect the clan.

A Wife shall sacrifice herself for her daughter at the age of twenty-four.

But tonight, the rules have been broken, and someone must pay.

Having heard Holly read some this aloud, I can also say it’s exciting and suspenseful. Holly was kind enough to answer some questions about the novel, and its unique format.

***

Holly McDowell

Me: Your book is a “serial novel,” a form that isn’t that common in contemporary literature. What made you decide to write it in this format, and what unique problems did you encounter?

Holly: I originally wrote King Solomon’s Wives as a full-length novel, but in the back of my mind, I always had the idea it could be a series. It’s about a secret society of women with an addictive touch who live in small groups spread all over the world, so there are plenty of opportunities for different points of view.

I might not have thought to make it a serial, however, if I hadn’t met the brilliant team at Coliloquy. Their experimental “Active Content” format uses choose-your-own-adventure links and lets readers vote on story elements. When I heard about it, I couldn’t wait to transform my story for the inspiring new platform.

As for problems… so far I haven’t found any! Each episode is a blast to write.

How many episodes will this story run, will they be collected in a single e-volume when you’re done?

Coliloquy is fabulous for this very reason; they’ll let me keep writing the story as long as readers want to read it! I have a big arc in mind, but I’m not constrained to a set number of episodes. I’m hoping I get to keep writing until the story feels complete.

You mentioned that you hadn’t read King Solomon’s Mines, which I incorrectly assumed your title referenced. What, then, were your influences on the story?

I remember the day I came home and wrote the first draft of the first chapter of the first version of this story… It was 2007! I’d been to a writing group meeting that night, and we’d discussed my love of Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale. I liked Atwood’s exploration of feminist themes through social and political extrapolation. I wanted to create a world where the challenges women face every day were exaggerated into an oppressive environment for the story. And I wanted to mix that with my love of history, of course.

Solomon was both a Biblical and Judaic figure of considerable importance. How do you address the religious aspects of the women’s history?

There was this pivotal moment in the real King Solomon’s life: he turned away from his religious beliefs to worship his wives’ gods. The change always intrigued me–the wives’ spirituality must have been something special to capture Solomon’s heart.

Without spoiling anything… I can say this particular historical moment was a major catalyst for the Wives’ millennia-long story. Naturally, their opinions on faith and religion are woven into their struggles in the modern world.

You’re also a musician, specifically a classical pianist. How does this discipline influence your writing?

Good question! There’s so much to learn from music. Any Beethoven Sonata is a perfect example of form, and it’s full of artistic substance. I think studying music must have given me some idea of how to start trying to learn form in writing. And I’m sure the daily hours of focused practiced helped train me as an introverted writer for those long weekends I’ve needed to spend at the computer.

Do you also compose music?

I do! Well, a little. My undergraduate degree was in music composition, and I’ve always enjoyed composing and arranging, especially for piano. Writing is my first love, of course.

Thanks to Holly for taking the time to talk to me. King Solomon’s Wives is now available here.

July 11, 2012

The face of the Firefly Witch

When a writer creates a character, he or she generally has a very clear image in his or her mind’s eye. Sometimes it can be of a well-known, specific actor: it’s no secret that Alien-era Tom Skerritt inspired Eddie LaCrosse, hero of my latest novel Wake of the Bloody Angel. Conversely, there is no actress who completely matches my idea of Bronwyn Hyatt, heroine of The Hum and the Shiver.

That’s what makes Tanna Tully, aka Lady Firefly, heroine of the Firefly Witch series, so interesting. When I first started writing about her, I had a very clear image of her in my head, although no actress entirely matched up. Then, sometime in the late 90s, I discovered So I Married an Axe Murderer, and Nancy Travis.

[image error]

Nancy Travis, my original idea of Tanna Tully.

She became my image of an ideal Tanna. And if someone had made a film of the stories fifteen years ago, I would have loved to see her in the part.

But now that I’m bringing back the character, updating her and writing new stories, I find Ms. Travis no longer quite fits what I have in mind. So, for those of you who’ve read the Firefly Witch stories, I have a question: what contemporary actress can you see as Tanna Tully? Leave a comment below, and you’ll get a chance at a signed novel of your choice.

July 9, 2012

A story as tight as a sharkbite

“The head, the tail, the whole damn thing.”

Every year on the Fourth of July, we watch Jaws. It’s the original summer movie, and the template for everything great about the blockbuster/tentpole approach. It’s also a really good story (and yes, it was a good story when Melville first told it, too, but that’s another post).

The book it is based on, however, is not. A really good story, that is. It’s what used to be termed a “potboiler,” with lots of disparate elements tossed in to hopefully create a kind of plot stew that gives everyone something to like. Yes, there’s a shark, and it does essentially the same things the one in the movies does. But the characters are unpleasant and not really admirable people, and in the end (SPOILER) the shark just sort of dies of an accumulation of injuries, it isn’t cathartically destroyed by the last remaining hero. Also in the book, the ichthyologist Hooper has an affair with Chief Brody’s wife. (END SPOILER) The film takes the skeleton of the plot and puts entirely new, and much better, meat and muscle on it.

Here’s the key: in the film, every moment, whether it’s a dinner, a city council meeting, or the moment the three heroes finally set out to sea, ends up being about the shark. Even though it’s barely glimpsed until two-thirds of the way through the movie, the characters talk about, or around, the shark in every scene. And this doesn’t result in shallow or dull characters: it results in focused characters, whose presence works actively for the story.

Consider the three heroes. Chief Brody, the transplanted New Yorker with a fear of water (blessedly never explained as a childhood trauma, or [as it would inanely be today] the result of a previous shark attack, or some such half-assed psychological nonsense), finds his character tested by the way he reacts to the shark professionally, and personally. He begins as someone willing to be pushed around, then gradually rises to the challenge and takes the action he knows is right. In contrast you have Quint, sole survivor of the worst shark-related disaster in history, who refuses to change, and pays the price for it. And in between is the jester, Hooper, who takes things seriously but always sees the absurd, especially in Quint and Brody.

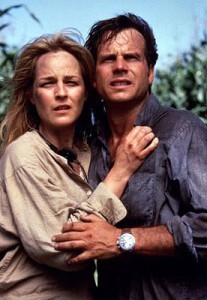

To see how badly a similar story can be done, check out Twister. The insipid romance between Bill Paxton and Helen Hunt, as well as third wheel Jamie Gertz, is given as much screen time as the tornadoes themselves. When you’re dealing with one of the most powerful and unpredictable forces known to man, you’ve got enough drama–tell your story about that, and about the way it impinges on the characters. Otherwise, why are you telling a story about tornadoes at all?

You mean our bland love is not as compelling as nature’s greatest destructive force?

Each time I watch Jaws, I pick another favorite line (this year it was, “That’s a deliberate mutilation of a public-service message!”). But I get the same shiver of appreciation at renewing acquaintance with a story perfectly told, the same shiver that I get rereading Ceremony or listening to Darkness on the Edge of Town. In each case, the creators (Spielberg, Robert B. Parker, Bruce Springsteen) stayed tightly focused on their story, making everything echo back to the central concept. And they each created a work that bears up to revisits, that continues to reveal new treasures to even the most dedicated fans.