Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 21

January 21, 2013

When to Plan and When to Pants

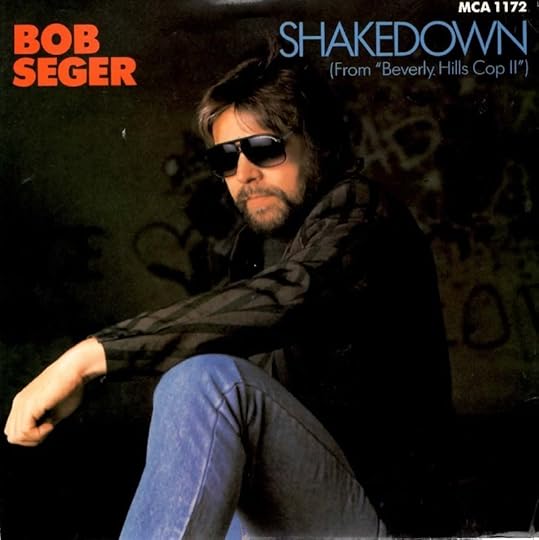

In the commentary on her video collection, Stevie Nicks says that the vocal on her hit “I Can’t Wait” is the first take, and that she knew she nailed it as soon as she finished. Bob Seger was called in at the last minute to record “Shakedown” when Glenn Frey got laryngitis; he also rewrote the lyrics, and got his only Number One hit out of it. Jack Kerouac wrote On the Road in essentially one long session, on a roll of paper so he wouldn’t have to stop and change sheets, with no punctuation or paragraph breaks.

What got me thinking about these three instances is a comment by British author DG Walker on her Twitter feed that said, “Planning is essential to the success of any undertaking and writing is no different.” Because I don’t neccesarily believe that.

Don’t get me wrong; I’m not saying you should never plan. If you’re a professional (or aspire to be), you have to be able to impose structure on your creativity. But writers use the term “pantsing,” as in “by the seat of your pants,” to describe writing without an outline, and with no predetermined goal or end. It’s something that, usually, can only be done with manuscripts that aren’t contracted for, deadlined or otherwise due in a set amount of time, situations in which you pretty much have to plan. After all, pantsing can lead you far astray from what ultimately becomes your story, and revisions can be a madhouse of slicing and dicing. But it also leads you to some of your best ideas.

There’s another element involved that isn’t mentioned in these examples, although it should be self-evident in the first two. At the time they recorded their songs, both Stevie Nicks and Bob Seger were long-time, successful musicians and songwriters. They had spent years honing the skills that brought them success and critical acclaim. And although he’d had no commercial success, Kerouac, at the time he wrote On the Road, had been working diligently to develop a unique narrative voice, something that had never existed before in American literature.

What does that mean for the rest of us, then?

When I teach writing seminars or classes, I use this example: a world-class athlete practices every day, so that s/he will be ready for the Big Game, which may only come once a year. Similarly, a writer should write every day, so that s/he is ready for the Big Idea. A lot of that writing will be pantsing, chasing an idea that may or may not go anywhere. But that time is not wasted, because the writer is perfecting the technical skills and critical judgment that only come from practice.

Stevie Nicks could nail that song in one take because she’d been singing for years. Bob Seger could step in at the last minute, rewrite and record a song that became his only number-one hit, because he’d been a singer and songwriter for over a decade prior to that. Jack Kerouac had been practicing a new form of writing, a prose version of what was happening in jazz music, for years prior to writing On the Road. All of these people, and pretty much every successful artist in any field, spends a lot of time pursuing ideas that, in themselves, go nowhere. But they lead to other ideas that do.

Planning is important: writing every day, having a good physical space in which to write, and so forth. When you have a deadline, you may have to plan how many words or pages you need to finish a day in order to make it. But never abandon the luxury of unplanned creativity, of literally chasing the dream to see where it goes.

Or, to quote Stevie Nicks, “I sang it only once, and have never sung it since in the studio. Some vocals are magic and simply not able to beat. So I let go of it, as new to me as it was; but you know, now when I hear it on the radio, this incredible feeling comes over me, like something really incredible is about to happen.”

And you don’t want to deny yourself that sort of feeling.

January 14, 2013

Available now: Hurricane Sandy benefit anthology

The Hurricane Sandy benefit anthology Triumph Over Tragedy is now available. It includes 41 stories for $6.99 (one of which, “Wrap,” is by me), so it’s basically only 18 cents a story. And all the proceeds go to the Red Cross for Hurricane Sandy relief.

January 7, 2013

You write like a girl (or boy)

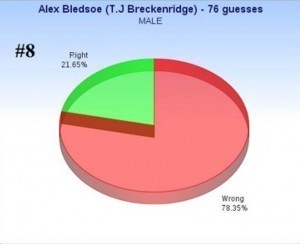

Today, instead of my own blog post, I want to redirect you to my friend Teresa Frohock. For the last two weeks she’s been conducting an interesting experiment in which I and several other authors submitted short pieces of original fiction under a genderless pseudonym (i.e., mine was T.J. Breckenridge) to test readers’ ability to identify a writer’s gender based solely on their words. Nearly 80% of the ones who read my piece guessed wrong.

You can see the other results for yourself here.

December 31, 2012

Film Review: Over Home: Love Songs from Madison County

Way back in the early years of this century (being able to say that makes me smile), the spark of the idea that would become the Tufa struck me at the National Storytelling Festival in Jonesborough, Tennessee. Also at that festival, I first heard Sheila Kay Adams at one of the midnight sessions, in a huge tent on a warm summer night. So her stories and music, and my fictional Tufa, have always been spiritually, if not literally, entwined.

Sheila Kay Adams

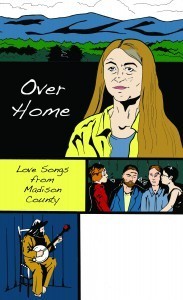

Sheila Kay is a traditional ballad singer, a woman who has dedicated her life to making sure that these old songs survive into the next generation. Over Home: Love Songs from Madison County is a documentary that takes us into her life, and shows how she’s passing on her traditions to the YouTube and iTunes generation. I first mentioned it here, when I interviewed director Kim Dryden during the film’s post-production.

The poster for “Over Home,” designed by Saro, who appears in the film.

You can watch the trailer:

and additional clips can be found here.

Sheila Kay learned these songs the old way, “knee to knee” on front porches from relatives who still gathered to share songs and stories when other more urban families were beginning to turn away from each other, to television, radio and other forms of passive mass communication. “They did not call them ballads,” she says in the film. “They called them love songs. And the gorier they were, the more I liked them. And if they mentioned cutting off heads and kicking them against the wall, I was all over it.” These were songs that came originally from Ireland, Scotland and other Celtic countries, brought with the first settlers and maintained intact among the isolated hills and hollows of Appalachia.

This is old stuff, literally and figuratively, if you’re a fan of my novel The Hum and the Shiver. But unlike my fictional Cloud County, the Madison County of this film is a real place, and the people you see in the film are genuine. Most compelling of the newcomers is sixteen-year-old Sarah Tucker, who bridges the traditional and the modern in a way that gives you real hope for the future of this music (and music in general). The scenery is expansive and beautiful, as are the Smoky Mountains themselves, but the most fascinating landscape of all is Sheila Kay Adams’s face as she talks about how music helped her persevere through personal tragedy.

Over Home is currently making the rounds of film festivals, and hopefully will soon be available on DVD and streaming. If it comes to a festival near you, definitely check it out (and if you have any pull in festival scheduling, I heartily recommend scheduling it).

December 26, 2012

Response to the NYT: Has Fiction Lost Its Faith?

Recently in the New York Times, writer and editor Paul Elie bemoaned the lack of depictions of Christian faith in modern fiction. He trotted out numerous examples of past masters (Flannery O’Connor, Anthony Burgess, etc.) and then mentions how current literary novelists simply don’t, apparently, have faith in Christianity. They don’t depict it because they don’t believe it.

In part, he said:

Now I am writing a novel with matters of belief at its core. Now I have skin in the game. Now I am trying to answer the question: Where has the novel of belief gone?

Well, to be blunt, it’s gone to those genres you look down upon. You know, the books people actually read: fantasy, science fiction, horror and romance.

Elie adds, The most emphatically Christian character in contemporary American fiction is the Rev. John Ames, who in Marilynne Robinson’s novel “Gilead” [published in 2004, and winner of the 2005 Pulitzer Prize--AB] writes, in old age, to his young son as he prepares for death in 1957.

Illustration from Paul Elie’s NYT essay.

Really? I mean, I can instantly think of two other examples of Christian faith depicted, rather emphatically, in recent fantasy novels that meet all Elie’s vague criteria. One is by me: in The Hum and the Shiver, from 2011, I have Craig Chess, a young Methodist minister new to his post and faced with the task of reaching out to a group of people who don’t believe in the same things he does (they have beliefs, but that’s another topic). Craig’s Christianity is genuine and heartfelt; further, he uses it as the touchstone for all his actions. He is content to let his Christianity show by example, not by proselytizing or haranguing. And this gets results: the novel’s protagonist, a young woman known for her past sexual exploits, is willing to honor his beliefs in their courtship. He neither demands nor expects her to change, and because of that, she both loves and respects him (and importantly, doesn’t change just to please him).

The other example is Miserere: An Autumn Tale, by Teresa Frohock. In this novel, she creates a cosmology that incorporates all the world’s religions, and more, shows them working together. The only place they don’t get along, in fact, is on Earth. In this universe, prayer functions as a real power that gets real results, and the strength of a prayer is measurable and crucial. Hell is a real place, and so is Heaven; and free will, the ultimate gift from God, has consequences. But there’s also redemption, God’s other ultimate gift, available to those who want it bad enough to truly change themselves and embrace the standards they have sworn to uphold.

I asked Teresa her thoughts on her approach to religion. She said, in part:

“I had to abandon the group-think mentality in order to write Miserere. I also want to be very clear: when I see or use the phrase “Christian belief,” I think of the teachings of the Christ and I automatically eliminate from my mind the trappings of doctrine and dogma, which were essentially organized and formulated long after the Christ’s death. Christian belief—as in love being the one rule of the law, protect the weak and those who stand outside the mainstream—those were the essential teachings of the Christ, and those beliefs heavily influenced Miserere.”

So, Mr. Elie, perhaps you should not bemoan quite so loudly. “Emphatically Christian” characters are all around you, just not in your myopic view of literature. Or, to paraphrase: there are more things in heaven and earth, Mr. Elie,* than are dreamed of in your limited literary philosophy.

*I was unable to find any website or contact information for Mr. Elie. I would love to include his response, if any.

December 17, 2012

The Blurring of Lines

Recently, while reading the Janet Sternburg-edited collection The Writer on Her Work, I had an unexpected epiphany (I know, epiphanies are always unexpected, but work with me). It was the realization that my life in 2012 is almost exactly Anne Tyler’s in 1980.

Tyler, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Breathing Lessons and The Accidental Tourist, contributed the book’s first essay, “Still Just Writing.” It begins with a list of all the real-world mundane events and responsibilities that keep her from writing when she wants to. The parallels with my own life right now–I’m the stay-at-home parent (or is the term “primary caregiver”? I can never remember) for two small children, and I write between events such as school, martial arts practice, acting class, various playdates and so forth–are pretty strong.* And I’m not the only one of my male writer friends in this situation.

The C-in-C back when we were full-time co-workers.

In all the essays in the book, the role of women in society forms a strong undercurrent. Comments from famous male authors explaining why women can’t be great writers (imagine hearing that in a college classroom now) are related, and examples from the past (Honor Moore’s tale of her grandmother who gave up painting because it was “too intense” is really fascinating) show how creative women struggled against both society and their own sense of isolation. In 1980 these struggles continued, but all the writers in the book have reached a point where they understand their desire to write is both irresistible and entirely acceptable, society be damned.

Now, the big difference with the life Tyler describes is crucial: thirty years ago, her life was the norm. It was what society expected women to do. It’s neither normal now, nor unheard-of, for the man to be the primary caregiver while the woman works out of the home. It is, in fact, a time when all the old roles described in Sternburg’s book are starting to twist and mutate. And sadly but perhaps inevitably, it’s being driven by economics, not social justice.

In fact, particularly within the so-called “creative community” of contemporary (and internet-linked) writers, artists and musicians, the traditional roles that Sternburg’s book discusses have certainly lost their edges, if not broken down entirely. Men can no longer find jobs lucrative enough to support their families; two incomes are the standard. In my case, my last full-time non-writing job did not pay enough to cover putting my youngest son in day care when he was a newborn. So I gratefully took the chance to become a full-time stay-at-home father, as well as a full-time writer. Both, for me at least, have paid off more than ever anticipated.

But are these changes permanent? Unless there’s a total collapse, eventually the economic system will recover, and jobs will become both better and easier to get. What happens to all these nontraditional families then? When the soldiers came back from World War II, women didn’t necessarily want to leave the work force to give the men back their jobs. And from that, eventually (it’s a hugely simplified explanation, I know) came the first modern feminist movement. So when jobs are again available, will men want to give up raising their kids to return to the traditional workplace?

I don’t know. We’ll see. But in the meantime, The Writer on Her Work has me looking at myself and my family with a whole new appreciation.

*Of course I don’t have her talent. That’s not what I’m saying at all.

December 14, 2012

Writer’s Day #7: A walk through the world of pirates

For this edition of The Writer’s Day, I share this summer’s visit to the Whydah exhibit, featuring artifacts from the only confirmed pirate ship so far recovered.

December 10, 2012

Rant: the high cost of low quality

Last night, the wife and I saw Skyfall. I’ve seen every James Bond movie in a real movie theater since Live and Let Die, so my streak continues. I thought Skyfall was an adequate spy thriller and action film, but not much of a James Bond movie. Perhaps, given how this one ends, the next one will be more of a return to the Bonds that had an element of distinctiveness. You’d never mistake a Bond for a Bourne back in the day, the way you can now.

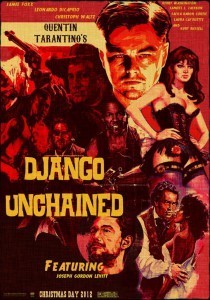

But we also saw previews for Jack Reacher, Django Unchained, and A Good Day to Die Hard, none of which did their job and convinced me I needed to see them. In fact, both Jack Reacher and Django Unchained reinforced my prior decision not to see them. And that, along with the trailer for the new Star Trek Into Darkness (which might as well be called Star Trek Jumping on the Nolan Bandwagon) hitting the internet, got me thinking seriously about something.

Why are we, as fans and consumers, satisfied with this?

JJ Abrams’ Star Trek was loud, noisy, and funny. It also had plot holes big enough for the Enterprise itself, and reduced one of SFs great heroes (James T. Kirk) to the status of a punk with a chip on his shoulder. I go into more detail here, but it’s the kind of movie that diminishes in retrospect, or with repeated viewings. Now there’s a new one, with a villain Abrams is playing coy about, only letting slip that it’s a “canon” figure. Khan? Gary Mitchell? Harry Mudd? Who knows? And more importantly, why should we care? Those stories have already been told, and told well. Yet here we are, as a demographic, getting excited about this movie when we should be ignoring it until someone comes along with some real, genuine new ideas.

The original “Django”

Similarly, Django Unchained, by virtue of being a Quentin Tarantino film, is practically guaranteed to be made up of parts of other movies, most obviously the spaghetti western Django series. More so than any other filmmaker working today, Tarantino has been praised for what is essentially sampling: taking bits and pieces of original creations and recombining them. He has yet to really create anything on his own, and it seems likely that this one will also have knowledgeable film buffs nudging each other and going, “You know where that’s from?”

The new “Django,” “unchained” from originality.

I understand completely the corporate mentality behind this: they’re known quantities, they’re existing properties, and most of the heavy lifting of creating them has already been done. What I really don’t get is why fans are excited about it. Another Star Trek movie that retreads vast swaths of the existing canon instead of “boldy going,” as its own damn catchphrase says? Bruce Willis, looking really old, in another Die Hard movie?

Then again, maybe I do get it, and just wish I didn’t. We’ve devalued our artists to the point that they can only make a living cranking new versions of old things. As a popular internet meme says, we’re willing to pay more for coffee at Starbuck’s than we are for music and literature. We justify piracy as entitlement. Girl of the moment Lena Dunham gets $3.7 million for this, while many formerly published authors are having to self-publish their own ebooks now.

And it seems we, as the consumers and fans, are satisfied with this.

I don’t have an answer. I wish I did.

The Blurring of Lines

Recently, while reading the Janet Sternburg-edited collection The Writer on Her Work, I had an unexpected epiphany (I know, epiphanies are always unexpected, but work with me). It was the realization that my life in 2012 is almost exactly Anne Tyler’s in 1980.

Tyler, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Breathing Lessons and The Accidental Tourist, contributed the book’s first essay, “Still Just Writing.” It begins with a list of all the real-world mundane events and responsibilities that keep her from writing when she wants to. The parallels with my own life right now–I’m the stay-at-home parent (or is the term “primary caregiver”? I can never remember) for two small children, and I write between events such as school, martial arts practice, acting class, various playdates and so forth–are pretty strong.* And I’m not the only one of my male writer friends in this situation.

The C-in-C back when we were full-time co-workers.

In all the essays in the book, the role of women in society forms a strong undercurrent. Comments from famous male authors explaining why women can’t be great writers (imagine hearing that in a college classroom now) are related, and examples from the past (Honor Moore’s tale of her grandmother who gave up painting because it was “too intense” is really fascinating) show how creative women struggled against both society and their own sense of isolation. In 1980 these struggles continued, but all the writers in the book have reached a point where they understand their desire to write is both irresistible and entirely acceptable, society be damned.

Now, the big difference with the life Tyler describes is crucial: thirty years ago, her life was the norm. It was what society expected women to do. It’s neither normal now, nor unheard-of, for the man to be the primary caregiver while the woman works out of the home. It is, in fact, a time when all the old roles described in Sternburg’s book are starting to twist and mutate. And sadly but perhaps inevitably, it’s being driven by economics, not social justice.

In fact, particularly within the so-called “creative community” of contemporary (and internet-linked) writers, artists and musicians, the traditional roles that Sternburg’s book discusses have certainly lost their edges, if not broken down entirely. Men can no longer find jobs lucrative enough to support their families; two incomes are the standard. In my case, my last full-time non-writing job did not pay enough to cover putting my youngest son in day care when he was a newborn. So I gratefully took the chance to become a full-time stay-at-home father, as well as a full-time writer. Both, for me at least, have paid off more than ever anticipated.

But are these changed permanent? Unless there’s a total collapse, eventually the economic system will recover, and jobs will become both better and easier to get. What happens to all these nontraditional families then? When the soldiers came back from World War II, women didn’t necessarily want to leave the work force to give the men back their jobs. And from that, eventually (it’s a hugely simplified explanation, I know) came the first feminist movement. So when jobs are again available, will men want to give up raising their kids to return to the traditional workplace?

I don’t know. We’ll see. But in the meantime, The Writer on Her Work has me looking at myself and my family with a whole new appreciation.

*Of course I don’t have her talent. That’s not what I’m saying at all.

December 1, 2012

The Dickens, I Say

The most famous Christmas story, besides the Biblical one, is without a doubt A Christmas Carol. Charles Dickens distilled the holiday spirit down to its essence with his tale of the miserly Scrooge who reforms his ways just in time for Christmas dinner. I love reading the actual story at Christmas, and watching my favorite* film version:

Yet take a step back from the many versions of this story, as well as the gargantuan list of other media (TV, radio, movies) that use it as a template and look at it from a fresh perspective, and Dickens’ accomplishment becomes that much more amazing.

The first edition of Dickens’ masterpiece

I mean, think about it: it’s a horror story, with genuinely scary ghosts (I defy anyone to not get a shudder from the Ghost of Christmas Future), a protagonist who advocates imprisoning children for debt, and its most sympathetic character (Tiny Tim) dies for lack of health insurance (okay, maybe not exactly that, but I stand by the analogy). Who puts all this in a Christmas tale?

A genius, that’s who.

Whatever his inspiration (and I’ve never researched it to find out), Dickens understood something basic about storytelling: the importance of balance. If his ultimate aim was to tell a heartwarming story for the holidays, he knew he had to even that out by adding dark, sometimes twisted elements that would balance the sweetness.

(You know who else understands this? David Lynch. In his best work–Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, even Twin Peaks–he balances the genuine affection the characters feel for one another with horrific violence and bleakness. But if there was only one element without the other, his films would be just like everyone else’s.)

How important is balance in a holiday story? Watch any Lifetime or Hallmark Christmas movie and see how insipid it is when it’s all sweetness and warmth. Without the darkness, there’s nothing to make the light stand out.

Nothing says Christmas like…AHHHHHHH!

When I set out to write “A Ghost and a Chance,” one of the stories in my holiday collection Time of the Season, I had a simple conceit: I wanted to drop my own Victorian/Edwardian Spiritualist character, Sir Francis Colby, into Dickens’ tale. Since I wrote about Colby in a faux Victorian voice, I thought it would be fun to use actual text from Dickens, and see if I could hide the seams between that and my own stuff. And it was fun. But it also made me recognize just what a gigantic accomplishment Dickens had managed. He gave us both a classic Christmas tale, and a legitimate horror story. He combined two genres that shouldn’t work together at all, and made them both complement and enlarge each other.

And it takes a genius to do something like that.

Want to see if you can spot the Dickens in my story? You can find it, along with two other holiday tales, here for only $2.99!

*Not saying it’s the best, just that it’s my favorite. I grew up watching it on WREG-TV out of Memphis.