Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 18

August 28, 2013

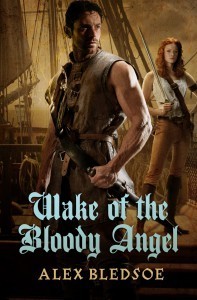

First hint for the new Eddie LaCrosse

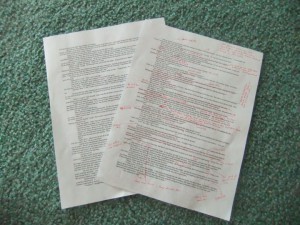

Since the next Eddie LaCrosse novel, He Drank, and Saw the Spider, doesn’t come out until this winter, I thought I’d start dropping some little visual hints about it. This picture contains a pretty obvious one: there is a sixteen-year-jump in the story. But if you can place the rest of the picture, you might also discern a few more things the book has in store….

August 26, 2013

Evie Let Your Hair Hang Down*

(Warning: SPOILERS!)

First, let’s get the criticism out of the way. The Mummy Returns is not as good as The Mummy. It’s repetitive, contains far too much CGI (something that would later overwhelm and derail writer-director Stephen Sommers’ career in Van Helsing), and the plot hinges on absurdities that not even genre films can easily accommodate (even I wince when the little boy is referred to as, “The Chosen One”).

But even with all that, it does something extraordinary with its female lead, Evie O’Connell. And few people seem to have noticed.

The Mummy introduced Evie as a bookish, clumsy Brit working in Egypt. She was almost a cliche: the beautiful woman who doesn’t become beautiful to the hero until she later takes off her glasses (and puts on a lot of eye liner). In her first scene, she trashes the entire Cairo Museum library. Later she makes several bad decisions, such as reading aloud from the Book of the Dead, that move the plot forward. But despite all that, she’s a resourceful woman who isn’t interested only in being the hero’s girlfriend: she also wants to be taken seriously as a scholar

A lot of her appeal, of course, comes from the actress playing her, Rachel Weisz. This future Oscar winner projects an innate intelligence and humor that fills in the gaps of the character as written, making her fully rounded (no pun intended) and compelling. To see how crucial this casting was, just check out the third film, where Evie was played by Maria Bello to no great effect.

At the end of The Mummy, Evie has fallen in love with adventurer Rick O’Connell, inadvertently acquired a fortune in treasure, and established (to her own satisfaction, at least) that she’s as good an Egyptologist as any man. It’s a suitable ending for the character as presented, and even though there’s a final clinch between her and Rick, it’s difficult to imagine a future in which the proper English lady and the shady American ne’er-do-well live happily ever after.

Except that’s just what they do, because of the kind of character development that you seldom see in the movies.

The Mummy Returns, although released only two years later, sees the O’Connells eight years after the events of the first film. They’re now married, and have an eight-year-old son, Alex. When the story opens, they’re on an archaeological dig in Egypt.

Already the film’s interpersonal dynamics are completely skewed. Rick, the dashing hero of the first adventure, a man who joined the French Foreign Legion and went off to find a lost city of gold, has apparently been domesticated. Clearly Evie is in charge, and more importantly, Rick is perfectly fine with that. They have a somewhat Nick-and-Nora air to their exchanges, implying that marriage (and subsequent parenthood) has not rendered their relationship stale. (As screenwriter and novelist Melissa Olson put it, “They ignore their kid to make out several times. Including when he dicks around with a supernatural device, leading to his kidnapping.”) Imagine any other hero of this sort of franchise–Indiana Jones, Jason Bourne, even Captain Kirk or James Bond–happily turning over the keys to his life.

And throughout the film, Rick is never the one with the ideas. He does plenty of fighting, but he’s never the clever one. That falls partly to their son Alex (who is depicted as a pretty good combination of his parents’ demonstrated traits), but mostly to Evie. She is the scholar, the one gifted with psychic visions, and the one who saves Rick at the climax instead of the other way around.

When Evie is killed, a helpless Rick begs his dying wife to tell him what to do. Our hero, the tough guy who carries the guns, is completely at a loss without his wife to guide him. Again, this is an abdication of the hero’s power you might find in an indie or foreign film, but in a big-budget, big-studio action movie? (And Rick is not the one who brings her back to life; Alex, their son, does that.)

[image error]

“Tell me what to do!”

But even our first look at Evie in the second film shows how things have changed. Gone is the demure, bespectacled librarian; in her place is a confident woman who doesn’t hide her attractiveness. And think about that for a moment. When’s the last time you saw a movie, or read a book even, in which marriage and motherhood made the female protagonist sexier?

You rightfully hear a lot of complaints about the way mainstream Hollywood depicts women. That’s why something like The Mummy Returns is so surprising. Whether it was there in Sommers’ original script, brought up due to behind-the-scenes machinations (Rachel Weisz’s career was certainly on the rise, and she may have insisted on a stronger character), or simply inadvertent, the fact remains that in this movie it’s the woman who makes the decisions, outsmarts the bad guys and saves the hero.

(For a similarly unexpected hero/heroine inversion, see my earlier blog post on Underworld.)

*This blog post’s title comes from this.

August 19, 2013

Writer’s Day: A Visit to the Tufa Library

Recently I had the honor of being invited to Rugby, TN, to do a reading and signing as part of their Appalachian Writers series. Rugby is the inspiration for Cricket* in the Tufa novels, and the real Thomas Hughes Library shows up as the Roy Howard Library. Here’s a glimpse inside.

*because I don’t work any harder naming things than I have to.

August 8, 2013

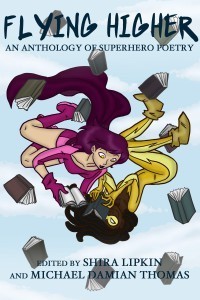

New Anthology: FLYING HIGHER

I’m not a poet. I feel I should say that at the outset.

But I have written a poem, “O Captain! America’s Captain.” It’s now part of this anthology:

It’s a labor of love, as they say. Editors Michael Damien Thomas and Shira Lipkin loved the idea, and they approached me and the other authors, asking us to channel our love for superheroes into poetry. Some, like mine, are less than serious; some are quite touching.

But all of them are FREE.

That’s right, the whole collection is available for just about every ebook platform, FREE.

Visit this link to download your copy. And if you like a particular poem, please let the author know.

August 5, 2013

Location, location, location

“Memphis is in a very lucky position on the map.”

–Steve Cropper

Facebook friend and fan Paula Cassidy recently asked me, “What’s the most difficult thing about using Memphis as a setting for some of your books?”

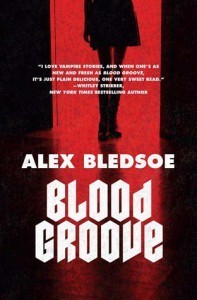

For those unfamiliar with them, I wrote two vampire novels set in 1975 Memphis, Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood (I hope to one day complete the trilogy with Blood Will Rise Again, but that’s another topic). Here’s a blog post I wrote about recreating the specific time period. But now I want to talk about geography, both actual and creative.

For those unfamiliar with them, I wrote two vampire novels set in 1975 Memphis, Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood (I hope to one day complete the trilogy with Blood Will Rise Again, but that’s another topic). Here’s a blog post I wrote about recreating the specific time period. But now I want to talk about geography, both actual and creative.

I was twelve years old in ’75, and visited Memphis many times, so I had some first-hand knowledge. But I was in my 40s and lived in Wisconsin when I wrote these books. Prior to writing them, the last time I was in the River City was in 2003, for a single night, to attend a Kate Campbell concert. And, of course, the city has changed quite a bit since I was twelve. The advent of Mud Island, the Pyramid, the revamped Beale Street, the closing of Libertyland, all were major alterations to the city I remembered. So it fell to research to add the flesh to the skeleton of my memories.

A lot of things can be found online, but there are simply some facts that Wikipedia doesn’t cover, and for that you need an expert. Luckily I found Theresa R. Simpson, the Memphis contact for About.com. She tracked down obscure information for me about the city at the time of my story, including particularly geography and history. If the books are accurate, it’s in large part thanks to her; anything that’s wrong, I take full responsibility for.

A lot of things can be found online, but there are simply some facts that Wikipedia doesn’t cover, and for that you need an expert. Luckily I found Theresa R. Simpson, the Memphis contact for About.com. She tracked down obscure information for me about the city at the time of my story, including particularly geography and history. If the books are accurate, it’s in large part thanks to her; anything that’s wrong, I take full responsibility for.

I learned something interesting about a story’s physical location through that whole process, and it’s informed my subsequent writing. It’s fine to use a real location, but unless you’re prepared to be taken to task by someone who knows the area better than you (and there’s always someone), it’s often better to create your own space. Show your inspirations if you need to: after all, everyone knows Metropolis is New York and Gotham City is Chicago, but it doesn’t stop us from enjoying stories of Superman and Batman. But with a fictional locale, you can tweak the geography to reflect the themes and events of the story in a way you can’t with a real place.

It’s actually two sides of how you approach telling a story. In one, you create characters who can live in a pre-existing world; in the other, you create an appropriate world for your characters. Both approaches are completely valid, but I find that my best work comes when I create the geography as well as the wildlife living in it.

Thanks to Paula Cassidy for asking her question.

July 29, 2013

Introducing the Siren

As some of you may know, last year my wife’s sister was tragically killed in a car accident. She left behind a little girl, now twenty months old, whom we have adopted, thus adding a fifth member to Team Pipsoe. So, friends and fans, I’d like you to meet my daughter, Amelia.

The Siren

When I talk about my kids online, I usually refer to them by nicknames. Long-time readers of this blog, or friends and followers on social media, know all about my older son, the Squirrel Boy, and my younger one, the C-in-C. After spending two days in a mini-van with Amelia bringing her from North Carolina to Wisconsin, a single term seemed appropriate, both symbolically and literally: the Siren. Like the sailors lured to their willing deaths by those mythological creatures, I would gladly sacrifice myself for this little one. And man, does her cry get your attention.

As the stay-at-home parent, I raised the C-in-C while still writing at least a book a year, so I anticipate no slowdown in my work. But if I’m a little less present online, and maybe don’t hit quite as many conventions next year, I hope you’ll understand why: I’m heeding the Siren’s call.

From left: the Siren, the Squirrel Boy, and the C-in-C.

July 17, 2013

No More Heroines

If you’re familiar with my work, you should immediately know I mean the word heroine, not the concept of the female protagonist. I’ve written one fantasy novel (The Hum and the Shiver) and a series of short stories (The Firefly Witch) with strong, tough female main characters, and I try to make the women in my Eddie LaCrosse series the equal of that hero; in fact, I hope to take Eddie’s sidekick from Wake of the Bloody Angel, Jane Argo, and make her the hero of her own novel one day.

And that’s the word I like to use. “Hero” should be a genderless term.

If the story has a main character, that’s the protagonist. He or she can be weak, sniveling, backstabbing or dishonest, and still remain the protagonist. But to be a story’s hero, you need to be more. S/he strives to make him/herself and the world better; s/he faces his/her darkest fears and pushes past them. S/he can still fail–look at both To Kill a Mockingbird’s Atticus Finch and Morgan from The Mists of Avalon–because it’s the striving that makes a character heroic.

Fantasy lends itself to heroes; in fact, there’s a subgenre called “heroic fantasy,” in which I proudly place Eddie LaCrosse (and I was tickled to have an Eddie story in volume 2 of the anthology series, The New Hero). But there’s nothing that requires that hero to be male, despite the cliche images associated with it. Sure, Conan is the first name that comes to mind when someone says “heroic fantasy,” but the Conan stories were written nearly a century ago. When he was adapted by Marvel Comics in the seventies, the creators knew that times had changed, took a minor character from an unrelated Robert E. Howard story, and created his female opposite, Red Sonja (whose latest comic incarnation will be written by Gail Simone).

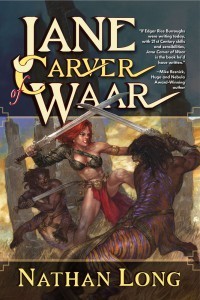

And today, female heroes are everywhere. I’m part of the Facebook group The Heroic Fiction League, and female heroes are thick on the ground there, whether written by women (Violette Malan, who has her own take on this issue here) or men (Nathan Long even has his own Jane, Jane Carver of Waar).

And yes, these are heroes, not “heroines.” They don’t need their own, gender-specific term, because their gender is irrelevant. What matters is their strength of character, not their strength of their (literal or metaphorical) sword arm. As Jodie Foster says in the DVD commentary track on The Silence of the Lambs, ”I think there’s something very important about having a woman hero, who’s a true woman hero in the most archetypal sense of the word, and yet doesn’t have to clothe herself in men’s clothing. She doesn’t kill the dragon by being mightier, she actually does it because of her instincts, because of her brain, and because somehow she’s seen something, some detail, that other people have missed.”

So I vote we abandon the term “heroine” and start calling everyone who deserves it, male or female, a “hero.” Who’s with me?

July 9, 2013

How Does Being a Southerner Affect My Writing?

Recently fan Laura Kannard asked me, “How has being from the South affected your writing?” I got a similar question during my recent appearance at Poisoned Pen bookstore in Scottsdale, AZ, so it’s been fresh on my mind. And it’s one of those questions for which there’s no easy answer.

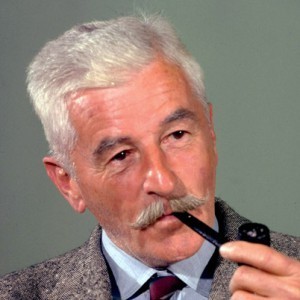

It’s clear that the South certainly has more than its share of critically notable and successful writers. From grand master WIlliam Faulkner to current best sellers like John Grisham, to fellow genre writers like Cherie Priest, Sherrilyn Kenyon and Charlaine Harris, the South produces writers at a pretty fair rate. This contradicts Southerners’ illiterate reputation; Faulkner even said, “Everyone in the South has no time for reading because they are all too busy writing.” And most of us, whatever our genre, eventually find ourselves writing about the South.

But we all experience the South differently. The Souths of To Kill a Mockingbird, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, and The Help are very different places, or at least very different facets of the same place. My own novels set in the South are not only different from these, but different from each other: I don’t see an easy way to reconcile the world of the Tufa novels (The Hum and the Shiver and Wisp of a Thing) with that of the Memphis vampire (Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood).

And in an odd quirk, many Southern writers invent fictional settings. Faulkner has his famous Yoknapatawpha County in Mississippi, and Charlaine Harris has Bon Temps in Renard Parish in Lousiana. This is not unique to Southern writers, of course, (I’m currently reading David Rhodes’ Driftless, set in the made-up Wisconsin town of Words), but perhaps because of the Southerners’ innate connection to their land (a topic for a whole other post), these examples seem somehow more vivid.

So, to get back to the question, how has my being from the South affected my writing? I’m aware of two very crucial ways.

One, it reminds me of the importance of prosaic personality details, especially in fantasy writing. Often, fantasy characters are separated from the real world of jobs, families, and especially, religion. You hardly ever see an epic hero who, when he’s not out epic-ing, has to do some humdrum job or even his part of the household chores (just imagine the many women Conan beds eventually yelling at him about leaving his skid-marked loin cloths scattered about). While there are plenty of politics and interfamilial treacheries to be found, the actual nature of relationships between and among family members (people who know they’re stuck with each other no matter what) are also rarely depicted. And religion is often a hypocritical force of repression and control, or else the defining quality of (usually) a supporting character; seldom do you see it as it happens in real life, as a loose influence on people who have probably been raised with its tenets but let them become guidelines rather than rules (or as the source of existential guilt when they fail to meet the standards).

Two, it’s inculcated me with the importance of the physical place to the stories that happen within it. The South is hot, damp and filled with wildlife, from bears to mosquitoes (I didn’t truly appreciate that last aspect until I moved to the Midwest, where the bug population is significantly less). Being hot all the time affects your mood; being sweaty makes your body move in certain distinctive ways (and often, not at all); and the constant influx of other life means, even in most cities, you never feel you’re that far from the country. In fact, except for Atlanta and possibly Birmingham, most Southern cities really don’t feel ‘urban’ in the way Chicago or New York do. When I’m creating a mythical place, whether contemporary, historical or fictional, I try to run it through this sort of filter to make sure I capture all the mundane details (mundanity?) of its reality.

Not an exaggeration; this is actually typical.

I’m sure there are countless other ways being from the South affects my writing; I mean, we’re all affected by where our personalities were formed. But most of those influences can probably be better discerned by the reader than the writer, so I’ll leave them to other people to parse. The ones I mention above are the ones that I consciously make part of my process.

Thanks to Laura Kennard for the question!

July 4, 2013

Three Questions on Writing

Recently my friend Talis Kimberley, an amazing songwriter and musician, asked me a couple of questions I thought might be of more general interest. So I thought I’d answer them here.

1: What are you proudest of having written?

That’s got a couple of answers.

Every writer has, in his or her head, an ideal version of their book. It’s graceful, powerful, and affects the reader unlike any book written before or since. Unfortunately, what we put on paper is often far below these lofty goals. We have bad word choices, poor characterizations, awkward prose and other similar but unavoidable discrepancies. Simply, we never get it right. As Da Vinci said, “Art is never finished, only abandoned,” and so we abandon our works when it seems we can do no more, or when deadlines arrive.

Every writer has, in his or her head, an ideal version of their book. It’s graceful, powerful, and affects the reader unlike any book written before or since. Unfortunately, what we put on paper is often far below these lofty goals. We have bad word choices, poor characterizations, awkward prose and other similar but unavoidable discrepancies. Simply, we never get it right. As Da Vinci said, “Art is never finished, only abandoned,” and so we abandon our works when it seems we can do no more, or when deadlines arrive.

However, one time I almost got it right. I remember reading the page proofs for the second Eddie LaCrosse novel, Burn Me Deadly, and realizing about halfway through that this was exactly the book I had in my head. Now I’m not saying it’s a great, or terrible book; that’s for readers to decide. But I can say that it was the closest to that “ideal” version that I’ve ever gotten. And I’m proud of that.

The second thing I’m proudest of is The Hum and the Shiver, because it was a first for me in several ways. It was my first fully contemporary novel that was not only set in the modern world, but dealt with modern issues. It was my first female protagonist. I used more of my own experiences in it than I’d ever done before. And I remain delighted and humbled by the response it continues to get from readers, two years after its release.

The second thing I’m proudest of is The Hum and the Shiver, because it was a first for me in several ways. It was my first fully contemporary novel that was not only set in the modern world, but dealt with modern issues. It was my first female protagonist. I used more of my own experiences in it than I’d ever done before. And I remain delighted and humbled by the response it continues to get from readers, two years after its release.

2. What have you read recently that made you think, “I wish I’d written that”?

The most amazing thing a reader can experience–and it’s magnified if that reader is also a writer–is the realization that someone you know, a person you might’ve interacted with on a daily basis, has created something awe-inspiring. The most recent example of that was the graphic novel Return of the Dapper Men, drawn by Janet Lee and written by Jim McCann. Jim and I used to work together, and while I knew he was a writer, I had no idea he was capable of the delicacy, heart and imagination of this book. Not only do I wish I’d written it, I wish I knew Jim better back in the day so I could’ve learned some of his secrets.

The most amazing thing a reader can experience–and it’s magnified if that reader is also a writer–is the realization that someone you know, a person you might’ve interacted with on a daily basis, has created something awe-inspiring. The most recent example of that was the graphic novel Return of the Dapper Men, drawn by Janet Lee and written by Jim McCann. Jim and I used to work together, and while I knew he was a writer, I had no idea he was capable of the delicacy, heart and imagination of this book. Not only do I wish I’d written it, I wish I knew Jim better back in the day so I could’ve learned some of his secrets.

3. Which parts of the process do you agonize over and which do you fly through?

That one’s easy, actually, because I deal with it every day. The hard part for me is always plotting. I generally don’t work from outlines: I just start writing and see where the characters take me. I’ll have a vague story structure in my head, but it’s malleable and often changes significantly through the process. Yet I admire writers who can concoct intricate plots that fall together with perfect precision by the end; they’re often not given much critical respect, but heck, even Raymond Chandler had to teach himself to plot by rewriting Erle Stanley Gardner.

Alas, his cat was no help.

The easiest thing is dialogue. I don’t claim any great talent, but for some reason I usually have no problem hearing my characters talk. Often my first drafts are simply page after page of dialogue that I go back and polish with attributions and description to make the scenes work. I don’t have the confidence to become another Elmore Leonard, who can write whole chapters with nothing but unattributed dialogue, yet he’s so good at it you’re never unclear about who’s speaking or where they are in relation to the other characters. But I do love writing characters talking to (or among) each other.

Thanks to Talis Kimberley for the prompt. If you have any other questions you’d like me to answer, leave a comment below and I’ll get to it as soon as I can!

June 24, 2013

Steam from manure: working with details

Recently on Facebook, fan Claudia Tucker asked me, “How do you decide what bits are superfluous even if it sets the ambience of the scene?”

Every writer’s approach, methods and habits are different, so keep that in mind when I describe mine. We all deal with the same issues, but ultimately there’s no right or wrong way to achieve these goals. The only thing that counts is what ends up on the page.

My first drafts tend to be very short. For example, the first complete draft of my fourth Eddie LaCrosse novel, Wake of the Bloody Angel, was right at 200 double-spaced pages, whereas the final draft was 420. That first draft consisted of scenes that conveyed only the essential plot information and basic characterizations. Description was minimal, transitions were abrupt, atmosphere and ambience was pretty much nonexistent. The point was to create the narrative spine of the whole story.

To continue with that skeletal metaphor, once the spine is complete, it’s time to add the ribs. Those are the secondary and supporting characters whose stories accent and echo those of the main characters. For example, in Wake, the hero Eddie LaCrosse is looking for another Eddie, the pirate Black Edward Tew; the more he discovers about his quarry, the more he finds parallels with himself (which was reflected in the book’s working title, The Two Eddies). He also works with another sword jockey (my term for a fantasy-world private detective), whose approach to the job makes Eddie think about his own career assumptions.

To continue with that skeletal metaphor, once the spine is complete, it’s time to add the ribs. Those are the secondary and supporting characters whose stories accent and echo those of the main characters. For example, in Wake, the hero Eddie LaCrosse is looking for another Eddie, the pirate Black Edward Tew; the more he discovers about his quarry, the more he finds parallels with himself (which was reflected in the book’s working title, The Two Eddies). He also works with another sword jockey (my term for a fantasy-world private detective), whose approach to the job makes Eddie think about his own career assumptions.

Each of these characters must also contribute something significant to the main plot, otherwise they don’t have a pressing reason to be in the story. And you, as the writer, need to hide all this careful construction so that the reader isn’t aware of it.

Once you’ve got the skeleton in place, it’s time to put on the muscle. In the case of my stories, the muscles are the emotional motivations and responses of the characters, based on what they’ve experienced in the past; in simpler terms, it’s the why. It’s very easy to have a hero* be brave when s/he faces the villain, but to make it resonate with the reader, you have to demonstrate not just how s/he’s brave, but why. Has s/he already lost everything, and feels s/he has nothing left to lose? Has s/he come to a new self-realization during the course of the story? Has s/he decided that the villain just has to be stopped, even at the cost of his/her life? Each of those potential sources of bravery makes the hero significantly different, and will also make readers experience him differently.

With that done, it’s time for the skin. Those are the things that bring the story to life in a mundane way. “Realism” is another term, and it’s incredibly important in science fiction, fantasy and horror. If you want people to accept your vampires, robots or elves, you have to establish their reality within the story by creating the kind of details that will support it.

The best example of this is a story I recall about either Norman Rockwell or Frederic Remington; I’m paraphrasing from memory, because I’ve been unable to track down a source. He was a young artist showing his teacher a painting he’d done of horses outside a saloon on a winter’s night. The teacher said, “How long have those horses been out there?”

“I don’t know. A while, I guess.”

“What do horses do when they’ve been standing outside for a while?”

So the artist added manure to the painting. When he showed it to his teacher, he was asked, “It’s cold outside, isn’t it?”

“Well, yes, it’s winter.”

“Fresh manure is warm, isn’t it?”

So he went back and added steam rising from the manure.

And that’s essentially what this “skin pass” is for: adding not just the manure, but the steam, and since we’re not just painting a picture, we have to add the smell and texture as well.

Of course, we’ve all read books where the author goes overboard on this, giving us not just the presence, smell and texture of the manure, but also the type of corn found in it, where that corn was grown, what the farmer was like and how he got along with his wife. The author has to know when enough is enough. Practice is the best way to learn this, and also keeping in mind one of http://www.writingclasses.com/InformationPages/index.php/PageID/304">Elmore Leonard’s rules for writing:

“Try to leave out the parts that readers tend to skip.”

Thanks for the question, Claudia!

*****

* I don’t like the word “heroine.” A character is either the hero, or not; gender is irrelevant.