Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 27

May 22, 2012

Dark Jenny mass market paperback release

Dark Jenny cover

Today the mass market paperback edition of the third Eddie LaCrosse novel, Dark Jenny, hits shelves. It includes a preview from the upcoming Wake of the Bloody Angel, one that’s different from the preview in the paperback of Burn Me Deadly.

There was no book trailer for the original release of Dark Jenny, but there is one for the new edition. Check it out below:

Want a chance to win a copy? Leave a comment before midnight on Memorial Day.

May 21, 2012

Interview: Filmmaker Sterlin Harjo

Sterlin Harjo at Sundance in 2007

Sterlin Harjo is an Oklahoma filmmaker with two extraordinary feature films under his belt. His first, Four Sheets to the Wind, is about a young man struggling to connect to the world after the loss of his father; Barking Water tells of two elderly lovers on a last road trip. Both are set against the background of Oklahoma Native Americans (Harjo belongs to the Seminole and Creek Nations), but they’re not special-interest films at all; they’re universal stories about feelings that we all have, against a unique and vivid cultural background.

One of the things that impressed me about the films was the tightness of the stories; it’s one thing to do a tight script, it’s another to do a tight one that feels loose. Both Harjo’s films seem to have a leisurely pace, presenting the unhurried minutiae of the characters’ lives, but by the end it all matters and it all has weight. It’s also significant that, whether due to budget or aesthetics, the movies are filled with the look, sounds and locations of real life.

Here’s an example of the kind of reality you won’t find in mainstream commercial cinema. In Four Sheets to the Wind, a character is awakened by a noise; now, strictly speaking, it could be any noise, from a barking dog to a coffee maker. But Harjo uses a truck’s squealing fan belt. Most mainstream filmmakers would have no idea what this sound even is, let alone what makes it, or what its presence says about the socioeconomic position of the family. It’s a real-life detail that conveys an awful lot in a simple noise.

Sterlin was kind enough to answer some questions for me about his approach to writing.

AB: Your two feature films have the common story element of people struggling to communicate. In Four Sheets to the Wind, Cufe is desperate for someone to really listen to him, and in Barking Water, Frankie and Irene are trying to repair a lifetime of miscommunication. Why is that theme of such interest to you?

SH: Not sure. There are a couple of themes that I deal with: communication/language and death. They always seem to find there way into my work.

I know you share a cultural background with your films’ subjects; how much of the actual stories also come from real life?

A lot of the characters are based on personalities that Im familiar with. Cufe in Four Sheets is based off my cousin, with a little bit of me in the mix. All the films have scenes or stories that have been adapted from real life. That’s really the only way I can write. That’s why my stories are culturally specific and set in Oklahoma.

One element that gives your films such impact is that, for the most part, everything is underplayed. There’s not a lot of histrionics, which is one reason the climax of Barking Water is so powerful. Do you know it’s going to have that tone from the moment you envision a story, or does it arise out of the material?

I always take the low key route. I just like subtlety. I am always striving to be truthful. I love how older Indians in my family tell stories. It can be about anything… about nothing, but the way they tell it makes it compelling. I love the films of John Cassavetes and Jim Jarmusch. Very different filmmakers, but neither care much for false reactions or theatrics. Both seem very real, in very different ways.

You mentioned Cassavetes: his films feel like they’re improvised, yet they’re not: pretty much everything is scripted. How do you use improvisation in your films?

I do improv, like Cassevetes, in rehearsal. But most everything is written.

4) One of my favorite comments about writing comes from screenwriter/director David Koepp, who was urged to eliminate the heavy Chicago accents in his film, Stir of Echoes: paraphrased, he says that the more specific you are with your characters’ reality, the more the audience will see the universal in them. As a reader/viewer, I’ve found that to be true, and I try to embrace it in my own writing. What do you think about that idea, and how does the concept apply to your work?

I agree. I think the more specific you get the more universal your story/film is. I always try to write from the characters perspective. Not the audience perspective. Because if you create a world where people can go into they will get into the film more.

Currently Harjo’s work is regularly featured at This Land, an Oklahoma-based arts project that includes a TV series of short documentaries (I’m partial to Indian Elvis). I appreciate him stopping by to answer some questions, and look forward to his future work.

May 14, 2012

The Curse of the Overwritten

I’ve been teaching a class for teen writers at the local library, and like any teaching job, the teacher gets as much out of it as the students. These kids are all there because they want to be, and they’ve proven through our first revision pass (my notes on their stories) that they can take editorial comments without freaking out. Even better, than can then implement those comments and improve their stories, often in ways the notes didn’t actually suggest. In other words, they’re real writers.

One particular issue, though, runs through all their work: a tendency to overwrite. They describe everything a character does, or the physical environment, in far too much detail. Their transitions, where a character leaves one location and goes to another, are especially problematic. This falls under number 10 of Elmore Leonard’s rules for good writing: Leave out the parts that readers tend to skip.

Now, me being a professional, you’d think I’d be long past that problem, right?

In my upcoming novel Wake of the Bloody Angel, my hero Eddie LaCrosse has to hire a ship to track down a pirate. He’s also brought along Jane Argo, a fellow sword jockey with a background in both piracy and pirate hunting. I wrote page after page, chapter after chapter, detailing how they found their ship, the Red Cow, and negotiated with its captain. I had them put together a hand-picked crew, each with his or her own story. And no matter how hard I tried, the whole section just sat there like a lump. Despite my best efforts, it seemed determined to be one of those Leonardian parts that readers tended to skip. I couldn’t figure out why I couldn’t write this any better.

The most boring part of any trip.

Then my wife, aka the smartest person I know, put it all in perspective. ”He’s basically buying a ticket. How exciting can that be?”

Boom goes the dynamite, as they say.

I deleted the chapters because, just like I tell the kids in my writing class, there’s no point in writing it if the reader’s going to skip over it looking for the next interesting thing. I put the whole section offstage, in the break between two realizations. One chapter ends with Eddie exclaiming, “Son of–” following one bit of insight, and the next begins “–a bitch!” after another. In the first, he’s on land. In the second, he’s already aboard the Red Cow, weeks into his hunt for the pirate Black Edward Tew.

I could have probably left that bit of overwriting in, and with a lot of effort gotten it presentable. But it would still remain unnecessary. And that’s the concept I’m going to try to convey to the kids in my class.

Because, hey: I’m long past that sort of thing myself. Right?

May 8, 2012

The Return of the Firefly Witch

I sold my first short story in 1996. It appeared in a defunct horror zine called Gaslight: Tales of the Unsane.

It introduced Tanita “Tanna” Tully, a character I subsequently wrote about for nearly ten years. She was: a) blind, but could see in the presence of fireflies, b) a parapsychologist, and c) a Wiccan high priestess known as Lady Firefly. The stories were told mostly in first person by her husband, a small-town reporter. These tales appeared sporadically through the early 2000s, mostly in PanGaia magazine. When my novels took off, Lady Firefly gave way to Eddie LaCrosse, Baron Zginski and Bronwyn Hyatt. I still occasionally get asked about her, though, by readers wondering if I’ll ever bring her back.

Wonder no more. Because Tanna Tully, Lady Firefly, is indeed back.

The cover for the first Firefly Witch collection

The first three-story chapbook, The Firefly Witch, will be available for download on Amazon beginning May 14 for only $2.99. The stories introduce Tanna Tully, her husband Ry, and their home of Weakleyville, TN, a small college town near the Kentucky border. They involve magic, romance, humor and a touch of Southern Gothic.

I had a couple of goals when I originally wrote these stories. I wanted to show that an established couple could be fun to hang out with, much like Nick and Nora Charles of The Thin Man (in fact, when asked to describe the stories, I often facetiously called them, The Thin Man Goes to Hell). I tried to depict actual Wiccan beliefs and practices seriously; that means it’s shown as a religion, not a hobby, and Tanna draws her strength and courage from it. And it was my first attempt to write something set in the contemporary South that I knew.

When I first tried to place them, the urban fantasy genre didn’t exist; they weren’t scary enough for the pure horror zines, and they were too scary for the pure literary journals. But much like the idea of a high fantasy detective series about a tough “sword jockey,” I knew the stories would eventually find a home. Now, thanks to technology and new ways of looking at old genres, they have.

This first collection tells how Ry and Tanna met, fell in love and got married. There are also ghosts, including what might be the first ghost in the world. Two of the stories, “The Chill in the Air Wakes the Ghosts Off the Ground” and “The Darren Stevens Club,” have been previously published; the third, “Lost and Found,” appears for the first time in this collection. Subsequent collections will include haunted roller coasters, psychopathic psychics, women who can blind you with their glow, and giant frogs.

For those who remember Ry and Tanna, I hope you’ll be tickled to see these stories available again. For those who don’t, I think you’ll enjoy them. They’re people I’d like to hang out with, if they were real. I’d love to discuss philosophy with Tanna, and join Ry for a beer at Cadillac’s.

I just don’t know if I’d want to visit a haunted house with them after dark.

April 30, 2012

The sources and settings for Wake of the Bloody Angel

Okay, so the fourth adventure of sword jockey Eddie LaCrosse, Wake of the Bloody Angel, hits shelves and reading devices this summer. What’s it about, you ask?

Pirates.

Why shouldn't I smile? I'm a goddamn pirate! Charlton Heston as Long John Silver in the best version of Treasure Island.

Oh, sure, there’s other things: the weight of the past, the nature of truth, the limits of friendship, sea monsters. But the selling point for me, the reason I wanted to write it, is simply that one word: Pirates.

See, not to brag (okay, maybe a little), but I was into pirates before they became cool again. Sure, I liked the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie; but before that I’d also liked the Errol Flynn triumvirate of Captain Blood, The Sea Hawk, and Against All Flags. I liked Burt Lancaster in The Crimson Pirate, and Tyrone Power in The Black Swan. I liked little-known pirate films such as Nate and Hayes, starring Tommy Lee Jones, and Swashbuckler, with Robert Shaw.

And before all those movies, there was the book: Treasure Island. It was the first “real” book I read to both my sons. It has everything a boy expects from a novel: action, adventure, suspense, a hero they can identify with, and one of the great lovable villains, Long John Silver. That it also involves pirates, and treasure, and castaways, and mutiny, and the lore of the mysterious Captain Flint, doesn’t hurt at all.

Maureen O'Hara puts Tyrone Power in his place in The Black Swan.

For each Eddie LaCrosse novel, I try to come up with a new setting. In The Sword-Edged Blonde, we traveled his world to learn about Eddie and his past; Burn Me Deadly concentrated on Eddie’s present, and the town of Neceda where he lives; then, after two novels where we met his friends, Dark Jenny drops Eddie alone and with no allies into the middle of an island kingdom, where he’s suspect number one in a murder. In each case, the idea was to both change the physical location, and a find a new way for Eddie to interact with it.

Errol Flynn as Captain Peter Blood.

So for Wake of the Bloody Angel, he goes to sea. With a crew of ex-pirates who are now pirate hunters, and in the company of Jane Argo, currently a sword jockey like Eddie, before that a pirate-hunter, and before that a pirate herself. His quarry is a friend’s former lover, the pirate who made the single greatest haul in all of recorded pirate history, then vanished with it.

That’s my skeleton. The muscles and flesh on it, though, are informed by a lifetime of watching and reading about swashbucklers in action. Eddie is no Tyrone Power or Errol Flynn (well, maybe the slightly-past-his-prime Errol of Against All Flags), but hopefully you’ll enjoy reading about his adventures on the high seas. And watch for more of the novel’s background and inspirations, coming soon.

Want to win an ARC of Wake of the Bloody Angel? Tell me about your favorite pirate in the comments (and make sure to leave an e-mail so I can reach you if you win). Contest ends at midnight, May 6.

April 23, 2012

The Pultizer Fiction Kerfluffle

Unfinished, and about boredom. One of the best three books of 2011? Really?

For the first time since 1977, the Pulitzer Prize committee chose not to give an award for fiction this year.

The responses have been vociferous and bifurcated (those are high literary terms for loud and split). It’s been denounced alternately as a flaw in literature itself, or in the committees doing the nominating and selecting, respectively.

The nominating committee–Michael Cunningham, a past winner for his novel The Hours, NPR host Maureen Corrigan and New Orleans Times-Picayun book editor Susan Larson–were, by all accounts, a reasonable group. You had a writer, someone who talks to a lot of writers, and someone who professionally reads and evaluates a lot of books. Together, according to this story, they read over 300 books in nine months. The three books they submitted were Swamplandia by Karen Russel, Train Dreams by Denis Johnson, and The Pale King by David Foster Wallace. Theoretically, the Pulitzer award committee would real all three, then pick a winner.

And that’s where it gets kind of squirrelly.

The one book entirely written by its author AND first published in 2011. Just sayin

Of these three books, only Swamplandia was a real, honest-to-God finished and current piece of writing. Train Dreams is a novella first published in 2002, which common sense says should disqualify it for an award ten years later (although the Pulitzer rules are pretty vague on who and what is eligible). And The Pale King (a novel about boredom, if you can believe it) was left unfinished at the time of Wallace’s 2010 suicide and subsequently completed by an editor, which means it’s not even all his work.

I haven’t read Swamplandia, but it certainly sounds like the kind of book that wins awards. The Pulitzer website calls it, “An adventure tale about an eccentric family adrift in its failing alligator-wrestling theme park, told by a 13-year-old heroine wise beyond her years.” Its author, Karen Russell, has already won a boatload of other awards for her fiction. So what happened?

We may never know. The Pulitzer folks are under no obligation to explain their reasoning, and can give (or not) their awards to whomever they want. But despite their denials it’s tempting to read into it a comment, if not an outright indictment, of the overall state of “literature.” There has always been a dichotomy between the books that sell and the books that critics love, but it’s rarely been a wider gulf than it is right now, thanks to changes in the book industry itself. Seldom has a more repulsive “writer” also been a bestseller than the likes of Jersey Shore’s Snooki, for example.

And really, Pulitzerati, you expect us to believe that an unfinished novel about boredom is better than every other book released in 2011, except two? Those sorts of critical blinders don’t help your case.

I have no answer or explanation for this. I’m happy to consider it an observation about the so-called “literary” genre that has abandoned such basics as good storytelling, some sort of moral perspective and even the basics of grammar (you’ll never find as many sentence fragments in a genre book as you do in some “literary” works). But ultimately it may tell us nothing, except how out of touch elite awards organizations can be. And that’s not news at all.

April 16, 2012

Guest Blog: Wonder Woman Redux

A few weeks ago, my friend Elizabeth Keathley wrote a guest blog here about the new run of the Wonder Woman comic. Recent issues have caused her to re-evaluate her original comments.

*****

Last month, I wrote a piece for this blog recommending the new run of Wonder Woman, based on the first four issues of the digital release. It is with a heavy heart that I return to rescind my recommendation, based on some rather strange story turns in issues five through seven. There’s not a lot I could write that hasn’t been written in detail, with page scans, by Colin Smith on his blog, but I felt I owed it to this audience to come back and explain that I don’t think the new comic is really so great anymore.

Image from the animated movie.

I’m not one of those people who would only be happy with an idea of Wonder Woman I have in my head. I thought the animated Wonder Woman movie was very good, despite it being far from the Wonder Woman I have in my mind. What I ask of WW writers is that they treat women, especially the title character, with respect. Wonder Woman is a feminist full of compassion – she’s a hero. Sadly the current DC misogyny creates an atmosphere of editorial bias that results in really crappy treatment of women. While never having the pleasure of meeting Dan Didio, his every response to questions regarding the current status of women in the DC universe can be justly characterized as hostile; see this response from last year’s Comicon as an example.

One gets the feeling that Didio is angry with women, or that he at the very least doesn’t think they should be allowed to play in his club house, which is weird since many women like myself were happily playing there before he came along and threw all our toys out the window and used the rest to make borderline porn. Sorry for the rant; I get passionate about Wonder Woman. My youngest daughter is named Diana.

David Willis also sums up how Didio’s approach to female characters is bad for business over here. Most frustratingly, it doesn’t matter how badly the current run of DC comics twists Wonder Woman or her Amazon sisters in the the marketplace of ideas. DC comics could publish a storyline so horrific that no one would ever buy Wonder Woman again, and the publishing run would continue. When William Moulton Marsten created Wonder Woman in the 1940′s, he signed a contract stating that if DC fails to publish a Wonder Woman title for 90 days, the rights to Wonder Woman revert to his heirs. DC almost dropped the ball once after Crisis on Infinite Earths (where Wonder Woman was actually killed off), and quickly ran a three issue filler storyline. That filler storyline, in which a classic Wonder Woman rescued a bratty little girl, was great. Afterwards she was rebooted again, and I wasn’t sorry; the new run by George Perez turned out to contain some of my favorite new Wonder Woman stories.

Gone are the days when I could maintain hope that one more reboot with a new writer might give me a good monthly Wonder Woman read. Alan Moore, who signed a similar deal for Watchmen, recently gave a sad interview about the current use of his Watchmen characters. It doesn’t matter how bad the new Watchmen comics are, DC will never go out of business because they own the liscensing rights to the originals. It doesn’t matter how bad the current Wonder Woman comics are, or if no one buys them, because DC makes loads of money from Wonder Woman lunchboxes, underwear, and toys.

Of course, those Wonder Woman products are bought by little girls who love their cartoon character, a hero who is strong and brave and kind, who hangs out with her friends in the Justice League and can be counted on to be a solid team player when the fate of the Earth is on the line. I wish I could say the same about the Wonder Woman in the current run of comics.

April 9, 2012

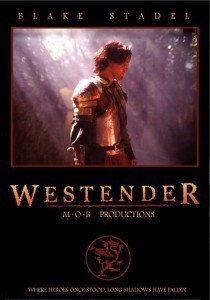

Interview: Jefferson Brassfield, screenwriter of Westender

The DVD cover.

I took a chance on the 2003 movie Westender, based on the DVD cover image to the left. I love fantasy films, and this one seemed unusually somber and even (dare I hope?) thoughtful, instead of the usually mayhem and scantily-clad girls (not that there's anything wrong with that).

It turned out to be just that: a meditation on redemption, shot in the forests of Oregon with a minimal cast and a lot of creative energy. It also backed up something I've always believed: that low-budget genre movies aren't terrible because their budgets are low, but because the people involved aren't very talented. Here's a low-budget film starring actors you've probably never heard of, shot essentially in the filmmakers' back yards, and it's just shy of brilliant.

I contacted screenwriter Jefferson Brassfield, and he was kind enough to answer some questions about this long-ago project.

Me: There's a melancholy, world-weary quality to both Asbrey, the hero of Westender, and the overall story. You were all pretty young when you made the film, so where did that come from?

Jefferson Brassfield: For me, I think that pathos came from the divorce of my parents in my teens and then my first real romantic heartbreak my freshman year of college. I tend to approach feelings with an Apollonian reverie more than a Dionysian embrace, and did so especially when I was younger. Those two world-shattering-to-me events were very difficult to process and express in my logical fashion, so they got internalized, compartmentalized. Keeping issues with that much personal gravitas unaddressed and unresolved will slowly grind a person down, infect them with a melancholy and world-weariness they may not understand. From that place, it was easy to find a voice in Asbrey, a soldier who solves problems with violence. Burden him with a broken heart; a problem that no amount of violence will resolve, and he is helpless. He will slowly disintegrate. We meet him on that decline.

I've found that the trick in fantasy dialogue is finding to the balance between period distance and emotional immediacy. Also, it's hard to suggest the speech of another time without sounding silly. Did you have any issues with that? How much of the dialogue in the film is directly from your script?

Most all of the dialogue is directly from the script, and I'm about 40% unashamed of that. For better or for worse, there's not that much dialogue in the film. We knew that we weren't dealing with a lot of serious, committed actors, so we didn't want to slather up the dialogue with incongruous accents and purple prose. If we went too far trying to be clever with period vernacular, we ran the risk of not being able to pull it off. If we went too contemporary, it might seem insincere. Since it was an ambiguous fantasy setting, we tried to straddle the line between those two without annihilating suspension of disbelief. It was definitely an issue we were conscious of. Some scenes Blake Stanton (Asbrey) would feel right away that what he was saying seemed wrong and we'd work to fix it, but most of the time we just went with the script and hoped it would all come together in the editing room. A few scenes were successful in that, a few scenes weren't.

How much of the visual symbolism was written, and how much discovered on set?

Most of the visual symbolism was conceived prior to filming. Westender was originally intended to be a long-form short film, and its structure grew out of two things: the locations in the Oregon wilderness we so loved and wanted to shoot, and the concept Brock (the director) had for the character of Asbrey. Blake and these gorgeous natural visuals were going to have to carry the film. Once I started working through the story itself, and once our short film became a feature, more appropriate symbolism emerged in the writing and brainstorming, and most all of it ended up in the movie. I'm trying to think of anything in this regard that arose in the moment or was realized in the editing room, but nothing is coming to mind. That stuff was all very conscious.

How much of a consideration was the budget to the writing process?

Huge. As I mentioned before, Westender was originally meant to be a lengthy short film, so we knew we were going to have almost nothing to work with, budget-wise. The locations, the story, the film-making, and Blake's performance were all we had. We couldn't afford anything more than that. No crowds, no stunts, no elaborate shots, no fancy sets, no visual effects, tiny cast, and tiny crew that were both willing to eschew a warm soft bed and personal hygiene for a week or two with no pay. A few scenes were shot on our shoe-string budget and then production halted for for a series of forces majeure I can't specifically recall. The footage was good. Brock pushed and fund-raised to make it into a bigger project. Once he had secured a healthier budget, we could make it into a feature with a few more bells and whistles, but we still had to cut every corner we knew we'd be turning. Not a heck of a lot was added into the script with our new budget, we just upgraded what was already there and what we already wanted to do. We could increase the amount of people to not pay.

How has the film affected your subsequent writing career?

We developed a Westender TV series with Gavin and Greg O'Connor, then it germinated at Paramount for a while, but it never happened. I really like the pilot script. I've written a few other screenplays, but nothing produced. I certainly feel like I've learned a lot from writing Westender. It's a flawed film, but it's the film we set out to make. I don't really have a writing career, so I reckon it hasn't affected my subsequent writing career too massively.

Thanks to Jefferson Brassfield for taking the time to talk with me. Westender is available on DVD, and through Netflix.

April 2, 2012

The wacky comradeship of the Beats

"New York gets god-awful cold in the winter but there's a feeling of wacky comradeship somewhere in some streets."–Jack Kerouac

I love reading about the Beat Generation. This is not the same, I hasten to add, as actually reading the work of the Beats, which can be hard going for someone used to more traditional forms of writing. But the idea of them–that there was once this group of friends who, through their individual and collected works, managed to change the literary world, and maybe the actual world–fascinates me. I've just finished Door Wide Open: A Beat Love Affair in Letters, and have begun The Typewriter is Holy: The Complete, Uncensored History of the Beat Generation. And later this year, the long-awaited film adaptation of the definitive Beat novel, On the Road, comes out.

So what appeals to me about these men and women who wrote like "slob[s] running a temperature," according to the Hudson Review? Why do I envy a group Charles Poore in the New York Times referred to as "a sideshow of freaks"?

Clockwise from left: Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Lafcadio Orlovsky, and Gregory Corso in 1956.

Like most writers, I'm a loner. I can't tell whether it's because of something in my personality or the world at large, but at this point it's habitual. I imagine most writers are like that, since writing by its nature is a lone, solitary activity. I don't mean I'm antisocial, or at least I hope I'm not. I try to be accessible and friendly. But the things that drive me, that are important to me and that guide my thinking…those things I keep to myself, for a simple and ironic reason: they're almost impossible to convey in words.

The original group at the core of the Beats found a way around that, though. They formed a network of friendships and other relationships, with poet Allen Ginsberg at the center of the web. They shared living quarters, adventures, and romantic partners, all with a raw-nerved intensity. Sure, I recognize that youth was a big part of it, as was the particular historical moment and heavy substance abuse. And there's no avoiding the narcissistic selfishness that kept them from more traditional connections (the only thing worse than being the romantic partner of a Beat was being the child of one). But even with all that, I envy their sense that here were people who understood, who got both the joy of being a writer trying to do something significant, and the sheer tedium of it. They got it.

Don't get me wrong, I have good friends who are also good writers. But we e-mail and post on Facebook, instead of sitting up all night in San Francisco coffee shops. We see each other at comfortable conventions, instead of flophouses or jails. Most of us are concerned with living healthy, so we don't chain-smoke or do hard drugs. Many of us have partners, and children, that we treasure. We're products of our era just as the Beats were of theirs. And perhaps if I were 29 instead of 49, these connections would have the same effect on me as those espresso arguments had on the original Beats.

But I'm not. I'm a middle-aged guy with two kids, a wife and a mortgage, trying to make it in a world where screaming has replaced talking. I don't have the option of dropping out the way the Beats did, or of dictating my own terms. And even if I did, I'm not sure I would; a number of the Beats ended up tragically, the result of an inability to handle substances and/or success. Their moment was fleeting, even for them.

Still, once they were the network of the cool: Ginsberg to Kerouac to Cassady to Corso to Burroughs, and so on and so forth. People who understood what the others were experiencing, what the struggle to create something meaningful was like. People who got it, man.

March 26, 2012

Tropes on the ropes: things I avoid

How I often feel about today's horror movies.

When I was a kid–and my kid-hood stretched well into my twenties–nothing in the horror genre bothered me. Some things made deep impressions, of course (the climax of Night of the Living Dead, for example, introduced me to nihilism), but it didn't trouble me or give me the kind of nightmares that make you swear off things. And I was up for anything, from the various Friday the 13th slasher murders to the lascivious decapitated head in Re-Animator. My absolute favorite horror film, Dawn of the Dead, remains one of the genre's goriest even now.

I'm not sure when that changed, or why. I only know it has. There are simply some emotions I have no desire to feel, especially in my "entertainment." I won't read or watch anything that I know includes them, and I'll turn something off or close the book if I encounter them with no warning. And I'm wondering if it's just me getting wimpy in my middle age, or if other people also experience this.

Not all of them are inexplicable, though. A big one for me is anything that focuses on the terror, pain or deaths of children. The source of that is easy, and I can hear it banging around downstairs as I write this. I've heard from other parents that that they've experienced something similar, so I know I'm not alone. It's a visceral, emotional response that I simply don't want to feel. I still get queasy thinking about a scene from American Horror Story where a doctor was sewing pieces of his dead baby together. If it makes me a wimp, then, I can accept that.

This year's model of the smug, petty villain.

A much more personal thing is the handsome, smug, petty villain. This one is new, and has manifested only in the past ten years or so. Watching Downton Abbey with my wife, I was totally unprepared for my reaction to Thomas the scheming footman: absolute, full-on rage. And while I understand that I'm putting his face on people from my own past, and that the rage is really directed at them and not the character, it doesn't help me "enjoy" the show. In fact, it sort of makes me dread watching it, much as I'd dread running into those same people. It's also kept me from enjoying many ostensible comedies, which often feature this sort of character as the main bad guy.

Getting back to horror, I also don't enjoy lingering shots of people in pain, which means I avoid the whole "torture porn" subgenre. The horror films I grew up with may have featured high body counts and outlandishly gory death scenes, but they didn't include lingering, almost pornographic shots of people (usually women) in agony. This started, in my view, with Wes Craven, whose cleverness goes hand-in-hand with his sadism, and became a genre of its own with the first Saw. Whenever I see one of these films advertised, I picture a bunch of twenty-something young men in a film editing room, drinking, farting and laughing hysterically at their own cleverness. It's the frat boy approach to horror, and as an adult, I have no interest in exposing myself to any more of it. (Whether horror even counts as an "adult" genre is something I've long pondered, and still haven't resolved for myself.) I'm also reminded of something Mike Nelson wrote:

"[It] makes one wonder how, with movie making being such a formidable task, requiring so much drive and vision, how could an individual choose to put so much ugliness on screen?"

I also don't enjoy creators who get readers/audiences emotionally attached to characters they plan to capriciously kill off. It's one reason I've avoided, and plan to continue avoiding, A Game of Thrones. It's not really a criticism, since this doesn't bother most readers and viewers, and of course drama must be able to include death. But I've lost enough real people in my life that I simply get no pleasure from losing fictional ones due to a creator's arbitrary decisions. And honestly, I feel this sort of thing violates an unspoken contract between creator and consumer. Real life is capricious enough; one reason I like fiction is the security of knowing that events will make sense. When they don't, at some level I feel betrayed.

I get less visceral reactions to some of the trite and obvious (not to mention unrealistic) tropes in more general forms of entertainment: the fat schlubby guy who wins the hot girl, sex scenes where the actress keeps her bra on, the whole Manic Pixie Dream Girl concept, the idea that immaturity is something to be treasured, and so forth. Part of it is simply that, as a writer, I recognize how false these concepts are. The rest is weariness: have you got nothing new?

And now, I'm asking you. What tropes/plot points/thematic elements do you deliberately avoid, and why? Leave a comment and you'll be entered to win a copy of the Burn Me Deadly paperback, which includes a sneak peek of Wake of the Bloody Angel.