Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 30

December 5, 2011

Review: Death Watch

The first volume of Ari Berk's trilogy.

I met Ari Berk at the Great Lakes Independent Booksellers Association annual banquet a few months ago; we shared a table as we each signed 200 copies of our most recent books. He was a great person to have beside me for such a repetitive and time-consuming task, and when he told me about his new YA novel Death Watch, I was instantly intrigued. Now that I've finally finished the book (a reflection of my own busy schedule, not the quality of the writing), I can say with all honesty that it's a great, moving read.

Although it's the first of a trilogy, Death Watch tells a self-contained story about Silas Umber, a teen whose father doesn't come home one night. Silas learns that his father was the "Undertaker" for the seaport town of Lichport, a job very different from simply arranging bodies for burial. To discover his father's fate, Silas takes over the position, learning about Lichport, its inhabitants, and his own devious and untrustworthy uncle. To help accomplish this, he uses his father's unique tool of the trade, the titular timepiece: when you stop its hands, you can see the spirit world.

Lichport is a sort of Lovecraftian Innsmouth Lite, where the supernatural is accepted as part of daily life. Just because someone's dead doesn't mean they don't hang around, both literally as re-animated corpses, or more figuratively as ghosts. Yet the dead are objects of sympathy, not terror, and the Undertaker's job is to help them find whatever peace awaits them.

This is a dense and detailed book, but you never get bogged down. And Silas is a wonderful protagonist: decent, tortured, trying to do the right thing but prey to the same doubts and fears as the rest of us, magnified by his growing knowledge of the afterlife. His courtship of Bea, the one girl in town who seems to like him that way, is touching in his acceptance of a relationship that, to put it mildly, has difficulties.

Berk tells the story in clear, clean prose that doesn't shy from attempting the poetic. Usually he succeeds, as with this passage about the ghost of a child:

A child sits by the tree on the playground. Every day it is the same. He sits by the tree. He does not look up anymore. No one comes for him. He can no longer remember what he is waiting for or how long he's been waiting. There is only the tree and the cold earth below him and the voices calling out from the yard, but they never once say his name.

(p. 472)

And my favorite line: "Honest error may play prologue to wonders." (p. 229)

The overriding emotions here are sorrow and loss, but this is far from a depressing book. Instead it reinforces the importance of memory, of keeping those you love close, and of trying to help others, both living and dead. And although it resolves all the plot issues it raises, it also leaves plenty of options for the rest of the trilogy. Death Watch is a great book, and I can't wait for the second volume.

Watch for an interview with Ari Berk, coming soon.

December 4, 2011

Announcing the second Tufa novel

The night winds and their riders will return.

It's official: there will be a second Tufa novel. Titled Wisp of a Thing, it will not be a straight sequel, but another story in the same setting, with many of the same characters. Release date, cover art, and back cover text are all to come. But I wanted to announce this during the holidays, to thank everyone who enjoyed The Hum and the Shiver and asked for more.

(Image from the insert of Jennifer Goree's second CD, Don't be a Stranger)

November 25, 2011

To Avoid Shark-Jumping

The writer trying not to repeat himself.

As I await the page proofs for Eddie LaCrosse IV (Wake of the Bloody Angel) and begin the first draft of Eddie LaCrosse V (so far, Eddie LaCrosse V), it occurred to me that every book in the series begins with two concepts, one of which is the same each time, while the other is very different. If you're out there and considering writing a series, this might be a useful thought process to explain.

First, the concept that's the same each time: how do I make this book different from the last, and from all the other books? Some elements simply have to remain the same, after all: the first-person narration, the hero solving a mystery, the anachronistic tone. But there are things that can be varied, such as supporting characters, location, and timeline.

For example, the first novel, The Sword-Edged Blonde, took place over the main character's entire lifetime, flashing back to his teenage years and his young adulthood. It also traveled all over his world, from the small town of Neceda to the sprawling seaport of Boscobel. Since at the time I wrote it, I had no idea that it would begin a series, I swung for the fences, packing in all the ideas I had for the character and his world. It was an epic, in everything but word count.

In contrast, the second one, Burn Me Deadly, deliberately took place in one locale and in linear time, and included lots of characters Eddie knew well. The third, Dark Jenny, was a tale told over a winter's evening about something that happened years before, set in a locale where Eddie knows no one. And Wake of the Bloody Angel, as the title implies, takes place at sea, again in linear time, and with Eddie having his first true sidekick.

But each book also has a core idea, a central thesis that provides the narrative litmus test for what works and what doesn't. In The Sword-Edged Blonde it was the Fleetwood Mac song, "Rhiannon": anything that didn't help evoke the same atmosphere as the song (and I realize that the song means different things to different people, so any given reader may go "huh?" at hearing this) was tossed, and since I nursed this story for years, it went down a lot of blind alleys. Having that core idea helped me eventually figure out the right direction for it.

Once I established this methodology, subsequent books became easier. In fact, each one could be broken down to a single term that guided the writing of both the narrative and the overall atmosphere. Burn Me Deadly: dragons=atomic weapons. Dark Jenny: King Arthur. Wake of the Bloody Angel: Pirates. Eddie LaCrosse V: the Wi–wait, I can't tell you that yet.

This combination of having a core idea and trying not to repeat the form of previous stories helps keep the Eddie LaCrosse novels different and exciting, at least for the writer. I've read my share of series where the author simply stopped trying to be different and essentially rewrote the same story over and over, whether from boredom, lack of ideas, or just to give the fans what they ostensibly want. I don't want to do that with the Eddie LaCrosse novels. Since they're all about the same character doing the same job in the same world, some similarities are inevitable. But my job as the writer is to make the rest of the elements as fresh and different as I can each time out.

How do your favorite series succeed (or fail) in keeping themselves fresh and interesting?

November 21, 2011

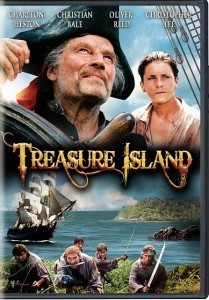

Review: Treasure Island (1990)

The spiffy new DVD cover

I've read Treasure Island many times, both for my own enjoyment and to my kids. It's a great novel, an exciting story and a splendid basis for a film. But only one of the many film versions gets it right: 1990′s version for television, directed by Fraser Heston and starring his father Charlton and a young Christian Bale. For years this has been inaccessible except for premium-priced VHS versions, but now it's finally on DVD in a splendid widescreen transfer.

In the popular consciousness, Treasure Island the novel labors under two misconceptions. One is that it's a story for children; it's not. It's written from the perspective of the grown man remembering his adventures as an adolescent, not as a preteen. So in both the MGM and Disney versions, casting Jim as a small boy fundamentally alters the story's dynamic. Christian Bale, on the other hand, is just right here. His adventures mark the transition from boyhood to the adult world, and he's a good enough actor even at age 14 to anchor the film.

The other misconception is that the pirates are merely colorful but essentially harmless rogues, especially Long John Silver. Wallace Beery is friendly to distraction in the 1934 film, and it's impossible to take Robert Newton's hammy portrayal in the 1950 Disney film seriously. But what else could be done with Jim cast so young? Silver in the book is a dangerous man, a real flesh-and-blood pirate, fond of Jim but still willing to kill him if it helped get the treasure.

Charlton Heston proves just right for the part. With his history of larger-than-life roles, he's got the stature and charisma to make the audience share Jim's affection for him. And he's a good enough actor that we buy him as a pirate, one vicious enough to intimidate the others.

The rest of the cast is just as solid. Oliver Reed nails the part of Billy Bones, while Julian Glover and Richard Johnson do solid turns as Jim's compatriots. Even Jim's mother, a thankless part as she's the only woman in the story, is given a fiery presence by Isla Blair. The other pirates, from Blind Pew (a scary Christopher Lee) to Israel Hands (Michael Halsey), provide the constant menace that the story requires.

But what makes it work so well is that writer and director Fraser Heston treats the story as a serious life-and-death adventure. Knives cut, shrapnel rips, blood flows and people die. The island is no tropical amusement park, but a dark and sweaty place where buccaneer ghosts might still prowl the shadows. Even the late Captain Flint, the man who buried the treasure and who is usually no more than a name, is given a sense of presence and reality.

This version of Treasure Island is the real deal: well-acted, exciting and faithful to both the letter and spirit of Stevenson's book. For those who've mistakenly considered this a tale for little children, first check out this film, then go back to the novel. You're in for a pleasant surprise.

November 16, 2011

Review: The Wages of Fear

American paperback cover.

I'm a long-time fan of the French film Le Salaire de la peur, a.k.a. The Wages of Fear, as well at its big-budget American remake, Sorcerer. Both tell essentially the same story of losers hired to drive trucks of nitroglycerin to extinguish an oil fire, and while the details differ greatly, the ultimate thematic point remains the same: the universe doesn't really care.

I read the original novel by Georges Arnaud many years ago, but recently re-read it and found a revelation. All I can say is…wow. From the perspective of 1952, Arnaud pegs the heart of economic darkness that still engulfs us today, and details its cost in lives, material, and broken spirits. It was true in the 1950s when it was written, in the 1980s when I first read it, and today.

Clocking in at less than 200 pages, Arnaud skips much of the character-building found in both film versions. He tells us enough so that we understand, if not exactly sympathize, with the men who undertake this dangerous mission. The main character, a Frenchman named Gerard, is a hard and bitter man who, like the other Europeans in the story, have fetched up in Guatemala for lack of anywhere else to land. When a distant oil rig is destroyed and the only nitro available is three hundred miles away, Gerard and three others are hired to drive two trucks (the assumption being one truck will probably not make it) of the stuff to the fire. The road conditions are treacherous, the tropical heat requires them to drive at night, and not all of them have the courage they profess. But the fear of the title is the real enemy, described in voluptuous prose:

Fear…it was there, riding on their backs, huge, mindless and oppressive. Fear in the guts, and nowhere to run to. Still, there is one thing one can do with fear: one can refuse to accept it. A special dispensation from the devil, and one rejects it. So then it waits, just outside the door. (p. 81)

This is not a cheery book about heroes by any means. It's about the courage of desperation, and the caprices of fate. It's also a rip-snorting adventure filled with detail about things the author clearly knows a lot about. I admire its lean, no-bullshit prose (translated, to be sure, but I bet it was just as hard-core in the original French). One of my own goals as a writer is to pare down each story to only the necessary bits, and this is a perfect example of it. It's also a lesson in pacing, the use of realistic detail and knowing how much is just enough.

Is it better than the movies based on it? Hard to say. Both are (rightly, to my mind) considered classics. Steven King even groups them together as the top of his "Reliable Rentals" list. The original novel is a slightly different journey to the same destination, and it shines a alternate light on a story that may be familiar from the films. And for writers, it's a master's-level lesson in the power of economy.

November 14, 2011

Interview: playwright Steven Stack

Playwright Steven Stack

Recently I attended the premiere performance of Welcome to the Neighborhood, a play written by Steven Stack. Steven also teaches acting at Forte Studios, and has written several other productions for them.

Welcome to the Neighborhood is set at a teen slumber party. Chloe, the new girl, invites three friends over. As they take magazine quizzes, Chloe realizes how little she knows them, and how well they know each other. And when white-masked faces appear at the window, she learns that being "different" may be deadly.

Thematically the play deals with the tension of fitting in versus being yourself, and it's dramatized by the identical white masks worn by various cast members. I asked Steve about the process of writing, and what effect he hoped to achieve.

Me: You had to balance a scary topic, the loss of individualism, with the demands of writing a play for kids. How did you determine where the line was?

Steven: Most of the scenes and plays I write have messages since teenagers are usually my primary audience, but I like to bury that message beneath layers and layers of story to avoid the preachy feeling that "message" plays can sometimes have. And it never ceases to amaze me what middle-school and high-school students can achieve on stage. The actors didn't let the mood of the story overwhelm them—they maintained an impressive level of professionalism. And no one in the audience fainted, as far as I know.

My goal with Welcome to the Neighborhood was to make it clear what the story is saying, while at the same time achieving a Twilight Zone-type effect for the overall mood. That way, the story isn't sacrificed for the sake of making a point. Focusing on the story and letting the message come from that actually made the message stronger (at least I hope so).

The ending built toward an expected payoff, which you subverted into ambiguity. What was the thought process behind that?

The original ending in the first draft had the expected twist ending, where Chloe made the decision to give up her individuality. But the more I thought about it, it just felt cheap and done for effect. On the other hand, I didn't want her to make the "right" decision because that felt like a feel-good ending that would be hard for the audience to connect with. So in the end, I left it up in the air, which felt more realistic: who knows what choice any given teenager would make? It depends on the day, the weather, their last haircut – there are so many variables to consider. So I had Chloe realize that even though she does an admirable job in general of staying true to herself, in the background that pressure to conform is always there.

What were the biggest differences between the play as you wrote it and the way it was finally performed?

The main difference from the first writing was that the focus at the beginning of the play changed completely. At first, I played up the horror aspects of the play by using lights, the neighborhood people, even creepy music to frighten the audience. As I continued to develop the play, I realized that I had placed the focus in the wrong place. Instead of the suspenseful elements, the early focus of the story needed to be on the characters – especially Chloe's family – and their relationships with one another. Not coincidentally, I realized this around the time that our daughter was born.

I also made some other character changes, including giving the menacing Officer Williams a deeper back story to make her more relatable for the audience. During the rehearsal process, the actors continued to connect with their characters, creating moments of further growth. Seeing the play performed with those changes in place was immensely gratifying. It's come a long way from its first form.

What do you want the audience–i.e., kids–to take away from this?

That the world is full of people who have lost their uniqueness, the special flair that they alone could have brought to the world, because of the relentless societal pressures they encountered to fit in and go along with what "everybody else does." It's a safer path, of course. But it's a tragedy when someone loses that joy that we all had when we were young, when we had no reason not to be ourselves and to let what made us special stand out. We're here for such a brief time and it saddens me to think that we still tell kids and adults that they have to be a certain way if they are to be accepted. The message of Welcome to the Neighborhood is that maybe fitting in and being accepted are overrated, and that the most important thing they can achieve with their life is to stay true to the person that they are on the inside.

Thanks to Steven for taking time to answer my questions.

November 8, 2011

The inappropriate cannot be beautiful

An appropriate background for paranormal romance?

(The title quote is from Frank Lloyd Wright.)

Recently I've read two books that put me in a surprising critical and moral quandary. Both were well-written, clever novels in the "urban fantasy/paranormal romance" genre. Both featured assorted supernatural creatures (vampires, werewolves, ghosts, etc.) with which the female protagonist was emotionally and physically involved. Both involved the triumph of good over evil in order to save the world, or at least part of it.

But here's the thing: both were set against the background of some of history's worst events: the aftermath of hurricane Katrina, and the events leading up to the Holocaust.

I'm a slow thinker, so it took a while for me to puzzle out what nagged at me about these books. Eventually I came to two conclusions. One was that each story was done very well, and would've worked just as well against a fictional background, or even a fictionalized version of the real events. The other was that the use of these real-life settings produced a crucial thematic disconnect between the events of the novel, and its chosen frame of reference. To me there's something uncomfortable about putting standard supernatural tropes (especially the watered-down* ones found in this genre) in these settings. I hesitate to use such harsh terms, but it does seem fundamentally disrespectful. Whole populations were wiped out or displaced, the dark side of our species was exposed for all to see, and we're expected to accept this as nothing more than background? The equivalent of Paris, or the Wild West?

Then again, it's not the first time this has happened. Probably the definitive example of inappropriate use would be the TV series Hogan's Heroes, which imagined life in a Nazi POW camp in which the commandant was a buffoon and the so-called "prisoners" secretly ran the show. TV Guide has named it the fifth worst TV series of all time, but it was quite successful for a generation of TV watchers who could still remember the war. So what does that say?

(Okay, that's not true. The definitive example is The Day the Clown Cried. Don't believe me? Read the synopsis.)

I don't know if this says anything about the world at large, or just me. I only know that it makes me uncomfortable to read about, say, vampire clans agreeing to help send Jews to the concentration camps. Other readers may not have the same issues. But I'm curious to hear your opinions in the comments.

*This is a personal bias, and I acknowledge it as such. The vampires, werewolves, and so forth found in most paranormal romance/urban fantasy novels are thinly-disguised versions of the "bad boys" of traditional romance, and as such, they no longer carry the symbolic or metaphorical weight of their former status as monsters. IMO.

November 2, 2011

Review: Heart of Iron

Heart of Iron

Ekaterina Sedia's Heart of Iron is the latest from a novelist who embraces genre–in this case both steampunk and alternate history–but brings a full-on literary sensibility to them. This, her fifth novel, posits a Russia where the 1825 Decembrist revolution succeeded (read about that history here) and the new emperor sets about modernizing Russia with a vengeance. But people will be people, no matter what machines they use.

Sasha, the protagonist, at first wants nothing more than to successfully debut at court. But driven by her strong-willed aunt, she enrolls as one of the first female students in St. Petersburg University, where she meets both Chiang Tse, a sensitive Chinese student, and Jack Bartram, a British subject better known to history as Spring-Heeled Jack. When foreigners of every stripe fall under suspicion and begin to disappear, Sasha investigates. Soon she and Jack must arrange an international alliance to forestall a possible world war.

This may sound like drawing-room docudrama, with the fate of nations decided in smoky rooms over tables laden with maps, but that's a misconception. This is a chase novel. Sasha and Jack are trying to get somewhere, and the villains–led by an alternative Florence Nightengale, wonderfully reimagined as the kind of upper-class screeching harpy only the British produce–are after them. There are fights, explosions, even martial arts (all worked legitimately into the narrative), and of course that classic steampunk trope, airships.

There's also a very deep and fundamental sense of the human cost of these events. Sedia doesn't just drily extrapolate, she brings to life both the pros and cons of her concept, showing us that even turning an historical failure into a success wouldn't necessarily make things better. And she makes Sasha a resourceful, strong-willed heroine whose voice gives us perspective on both the world around her and her own emotional life with the same cool honesty.

Ekaterina Sedia is one of the few authors whose books I grab as soon as they appear. Over five vastly different novels she's quietly staked out a unique territory in fantasy, and deserves far more attention than she's gotten. Heart of Iron is a both a great introduction to her work, and a rollicking great read on its own.

October 31, 2011

The return of Sir Francis Colby

Haunted: Eleven Tales of Ghostly Horror

For Halloween, I thought I'd tell you the story behind my latest foray in the horror genre.

When I decided to write my first vampire novel, Blood Groove, I had a problem. Its name was Count Dracula. As the gold standard of vampires, his cape cast a very long shadow. Every literary vampire, from Lestat to Edward Cullen, is measured against the king of them all, and I knew mine would be as well. I needed a vampire that could stand side by side with the legendary count, so that I could both pay homage and tweak this convention.

Fortunately, I'd already created a vampire like that in my short story, "On the Count of Z." Unfortunately, that story was written mainly as a parody, part of an ongoing attempt at Victorian pastiche. The hero, Sir Francis Colby, was equal parts Van Helsing, Conan Doyle and Churchill, and in other (unpublished) stories he battled gargoyles and even Frankenstein's monster. His encounter with the vampire Baron Zginski was goofy in the extreme, hinging on the great Spiritualist's observation that Zgisnki didn't actually breathe. But when I rewrote the story's framing sequences so that they took place in the novel's 1975 Memphis setting, it worked like a charm, and I had chapter one of my novel. That also became the world's introduction to Sir Francis.

Many of my favorite "writers of the fantastic" were from the Victorian era, or wrote as if they were: Arthur Conan Doyle, Arthur Machen, HP Lovecraft, Edgar Allen Poe. In the short promotional film for Blood Groove (see it on my "Media" page), director Lisa Stock used a very famous Victorian vampire author as a stand-in for Sir Francis. The described a world torn between the enlightenment of technology and the pull of superstition, in which we ignored those things in the dark at our own peril. And they wrote and spoke in a vivid, vaguely purple language that still delights me. I mean, shouting men were described as having verbally "ejaculated," at which the ten-year-old in me still giggles.

When I was asked to contribute a story to Haunted: Eleven Tales of Ghostly Horror, I recalled a Sir Francis story that I'd never quite finished. It involved a radio for speaking to the dead, and as all the Sir Francis tales had punny titles, I called it, "What's the Frequency, Francis?" after the R.E.M. song, which in turn was inspired by a bizarre event in the life of newsman Dan Rather. I unearthed and revised it, adding a little dig at the current crop of "Ghost Hunter" reality shows. It came together, I felt, quite nicely. Fortunately so did the editors.

With the current steampunk boom in full swing, I've considered writing a whole Sir Francis novel. But as a reader I have a low threshold for pastiches, and I just don't know if I could sustain the tone for that sort of length. Still, there are plenty of finished and half-done short stories featuring this character, so he might show up again. For now, you can find him hunting vampires or saving the world from malevolent ghosts. And ejaculating.

October 26, 2011

Guest blog: Alana Joli Abbott

Alana Joli Abbott

Today's post is by Alana Joli Abbott, a fellow contributor to Haunted: 11 Tales of Ghostly Horror. Here she talks about the origin of her story, "Missing Molly."

***

One of my jobs, when I worked at the reference desk at my local public library, was to scan the local newspapers for articles about our town to clip and put in the archives before the papers went for recycling. But one day while clipping, it wasn't news from my town that caught my eye: instead, it was the story of a tombstone in Milford, Connecticut that had gone missing from its graveyard. Since I was clipping news from several newspapers of the same week, I hurried ahead to see if there was any conclusion to the tale – and if anyone had stepped up to claim the $500 reward.

In fact, the cemetery's superintendent followed some drag marks near the stone's former location that led into the nearby woods. There was the tombstone, none the poorer, of the infamous Mary (Molly) Fowler, made known not for any deeds during her late eighteenth century life, but for the insulting inscription on her grave marker. It reads:

Molly tho pleasant in her day

Was suddenly seiz'd and sent away

How soon she's ripe how soon she's rott'n

Sent to her grave and soon forgott'n.

"There has got to more to the story than this," I remarked to a coworker, who knew I was a fan of urban fantasy.

"Vampires?" she suggested.

"Oooh, an urban fantasy turf war!" I responded.

Because the article was from a different town and didn't need to go into our files, I clipped it and kept it for myself, waiting for the right moment for a story to happen.

Fast forward a couple of years to a call out from Flames Rising editor Matt McElroy. Matt and anthology editor Monica Valentinelli were looking for stories of ghost hunters. I had an idea in mind based on the ghosts and magic of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and so I started off on a paranormal mystery featuring a ghost summoner and her bodyguard. Though I liked it, it wasn't a good fit for the anthology (it'll turn up somewhere else eventually, I hope!), and with only a few days left, I had to either give up the opportunity to submit something or come up with a new idea.

That's when I remembered Molly.

[image error]

"Haunted: 11 Tales of Ghostly Horror"

I dug through my research (a sum total of those two 2009 newspaper articles) to see if it struck any ideas that would work for the call for submissions. And that's how I met Angie and Wes, two fans of Arthur Conan Doyle – one who hunts ghosts and one who is haunted by his past. Though the original version was more of a Sherlock Holmes pastiche than the version that appears in the anthology (thanks, with gratitude, to Monica, who saw what parts of the story were working and what parts needed to go), the final incarnation owes its greatest debt to Molly Fowler, whose gravestone went missing and returned within days of its theft.

May she rest in peace.