Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 33

August 18, 2011

Celebrate Noir Week at Tor.com with me!

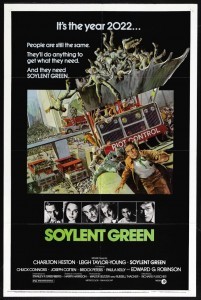

As part of Noir Week at Tor.com, I'm blogging about the classic film Soylent Green.

As part of Noir Week at Tor.com, I'm blogging about the classic film Soylent Green.

August 15, 2011

New website!

August 11, 2011

Torchwood: For grownups, but not by them

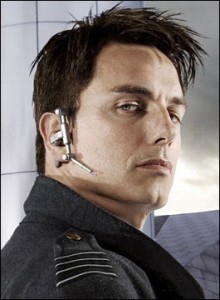

Captain Jack Harkness,

who is VERY pleased to meet you.

As part of our immersion into the universe of Doctor Who, the management staff at Chez Bledsoe has been watching the first season of Torchwood. Basically an English (well, Welsh) version of The X-Files, it's about a super-secret team who deal with otherworldly and paranormal dangers that beset contemporary Cardiff.

It doesn't take many episodes before you realize that the Torchwood team is its own worst enemy. Whatever the qualifications for joining, they seriously need to be rethought: in nine out of the ten first episodes, the primary danger is caused by a member of Torchwood (and in that tenth episode, nothing happens. Pretty much literally). The cast is interesting, the budget more than adequate, and the premise rich. So what's wrong?

Torchwood tries very hard to be cutting edge, especially in its approach to sexuality. The leader, Captain Jack Harkness, will, ahem, shag anything that moves–male, female, or other–as long as it's gorgeous. Computer whiz Tosh has a lesbian fling with an alien disguised as a human woman. Gwen and Owen, two team members, have an ongoing affair, and it's implied that uptight Ianto and Captain Jack have an occasional after-hours tryst. None of these are bad ideas, but they're also not thought through. The writers have people shagging for no apparent, logical reason except that it's titillating.

And that's when I realized what was fundamentally wrong about the show.

Torchwood feels like a fifteen-year-old's view of how adults act. Since most teenagers are obsessed with sex, so are the Torchwooders. But since most fifteen-year-olds don't have a lot of experience with sex, the relationships feel forced and phony, more like masturbatory fantasies than real encounters. Most teens have never held jobs, let alone jobs with responsibility, so they imagine worksite conflicts that simply wouldn't occur among highly-trained and supposedly elite team members. Instead of professionalism, we get playground arguments transposed to Torchwood HQ. Fights break out, but like playground fights, the next day they're forgotten–even when one team member threatens another with a gun.

I doubt that the writing staff on Torchwood is seriously fifteen years old. Instead they're likely the same kind of "talent" you see everywhere now: people raised on movies and TV who have gone into the industry at such a young age that they have no real life experiences to bring to their writing, only bits and pieces of other shows and movies. In some cases, such as the films of Quentin Tarantino, that's enough. Here it's not.

We'll probably continue watching the show, alternating it with Doctor Who. I've heard from multiple trustworthy sources that season 2 gets much better. And perhaps it does; after all, fifteen-year-olds do eventually mature, even if only a little bit.

August 10, 2011

Torchwood: For grownups, but not by them

Captain Jack Harkness, who is VERY pleased to meet you.

As part of our immersion into the universe of Doctor Who, the management staff at Chez Bledsoe has been watching the first season of Torchwood. Basically an English (well, Welsh) version of The X-Files, it's about a super-secret team who deal with otherworldly and paranormal dangers that beset contemporary Cardiff.

It doesn't take many episodes before you realize that the Torchwood team is its own worst enemy. Whatever the qualifications for joining, they seriously need to be rethought: in nine out of the ten first episodes, the primary danger is caused by a member of Torchwood (and in that tenth episode, nothing happens. Pretty much literally). The cast is interesting, the budget more than adequate, and the premise rich. So what's wrong?

Torchwood tries very hard to be cutting edge, especially in its approach to sexuality. The leader, Captain Jack Harkness, will, ahem, shag anything that moves--male, female, or other--as long as it's gorgeous. Computer whiz Tosh has a lesbian fling with an alien disguised as a human woman. Gwen and Owen, two team members, have an ongoing affair, and it's implied that uptight Ianto and Captain Jack have an occasional after-hours tryst. None of these are bad ideas, but they're also not thought through. The writers have people shagging for no apparent, logical reason except that it's titillating.

And that's when I realized what was fundamentally wrong about the show.

Torchwood feels like a fifteen-year-old's view of how adults act. Since most teenagers are obsessed with sex, so are the Torchwooders. But since most fifteen-year-olds don't have a lot of experience with sex, the relationships feel forced and phony, more like masturbatory fantasies than real encounters. Most teens have never held jobs, let alone jobs with responsibility, so they imagine worksite conflicts that simply wouldn't occur among highly-trained and supposedly elite team members. Instead of professionalism, we get playground arguments transposed to Torchwood HQ. Fights break out, but like playground fights, the next day they're forgotten--even when one team member threatens another with a gun.

I doubt that the writing staff on Torchwood is seriously fifteen years old. Instead they're likely the same kind of "talent" you see everywhere now: people raised on movies and TV who have gone into the industry at such a young age that they have no real life experiences to bring to their writing, only bits and pieces of other shows and movies. In some cases, such as the films of Quentin Tarantino, that's enough. Here it's not.

We'll probably continue watching the show, alternating it with Doctor Who. I've heard from multiple trustworthy sources that season 2 gets much better. And perhaps it does; after all, fifteen-year-olds do eventually mature, even if only a little bit.

August 2, 2011

Publishers Weekly reviews THE HUM AND THE SHIVER

August 1, 2011

Genre respect and the NYT

Still, it's frustrating to still see this play out right in front of me, as it did last month in the New York Times. I won't use the authors' names here, because it's not important; it's not hard to figure out of you feel the need, but it's utterly beside the point. To me, what's important is how this "corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals" (props to Spiro Agnew) pronounces and supports its judgment.

Here are two excerpts from the literary novel's review:

"So does the new novel deliver? I'm not so sure...the author seems a bit lost, adrift in unfamiliar waters, and the book feels less like a second novel than it does another try at a first."

"There is only so much we can read this way before we are overwhelmed by the desire to drop the pretense."

And here are two from the review of the genre novel:

"[The author's] novel has the stylized quality of books by Angela Carter like The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman, and it displays similar pyrotechnics."

"Yet in a highwire act of her own, [the author] still raises the novel above the ordinary through her ability to convey the richness of the [characters'] emotional lives, coupled with impressive writing."

Clearly the first review was less than positive, while the second was close to a rave. Now, the kicker: which book got the three-page excerpt also published in the New York Times? That's right, after their reviewer says "There is only so much we can read this way before we are overwhelmed by the desire to drop the pretense," the Times decides to put that to the test.

As I said, I mean no disrespect to either writer. I do mean disrespect to this constant shafting of the genre in which I work, in which a lot of people do great work that readers actually want to read. How do I know? You don't get David Foster Wallace conventions; you do get Terry Pratchett ones.

But perversely I also enjoy this lack of respect. Like Superman and Lex Luthor, or Batman and the Joker, your hero is measured against the strength and cunning of the villain opposing him/her. And when you get right down to it, the Literary Establishment is actually a lot like Lex Luthor: powerful, entrenched, sophisticated, and--most delightfully--fundamentally threatened by those aliens in their brightly colored costumes.

July 31, 2011

My favorite science fiction joke

July 25, 2011

Age ain't nothin' but a...problem

The original detective heroes like the Continental Op and Philip Marlowe didn't face this worry. Their series were relatively short compared to what we now consider a successful run: seven novels and some short stories for Marlowe, compared to 21 for John Sandford's "Prey" series; Agatha Christie's Miss Marple racked up 12 novels, against 40 for Robert B. Parker's Spenser. Sam Spade, the quintessential tough-guy detective, exists in only a single novel, The Maltese Falcon.

The appetite for series now requires at least a book a year, and authors with contemporary settings have to face the fact that the world changes around their heroes. Do the heroes change with it? Some do. James Lee Burke's Dave Robicheaux, once young enough to be played in a movie by Alec Baldwin, is now 73. Michael Connelly's 60-year-old Harry Bosch has to deal with the vagaries of contemporary retirement. But some, like Spenser or Kay Scarpetta, don't. In fact, the biggest surprise in the article was how many authors began with their heroes aging, and then arbitrarily froze them in time when the series became successful.

It made me think about Eddie LaCrosse's age, and how that affects his ongoing adventures. I created his prototype character when I was 18, but I wanted him to be worldly and sophisticated, so I made him roughly 35, which is his age in The Sword-Edged Blonde. At the time I thought that was mature enough to give him the perspective I wanted. However, by the time the book actually came out I was over 40, which meant I was now writing about a character a decade younger than me. Further, and strange as it seems, I'm continuing to age. So I'm faced with the dilemma of what age Eddie should be in each book.

Luckily I'm freed from the worries of the modern world, since Eddie's world is fantasy and only changes when I change it. But I still want him to be believable, and part of that is aging. I don't have a set time frame, like Stephanie Plum (Kinsey Millhone ages one year for every 2 1/2 books, so she'll be about 40 when the series concludes). But he does progress. In the framing story of Dark Jenny I think he's about thirty-eight, settled into his relationship with Liz and established in Neceda. In the next book, Wake of the Bloody Angel, he's about the same age. Which works out to real-time again, one year per book, by default. But it's not deliberate, therefore I can't be held to it. Ultimately, Eddie's as old as I say he is.

July 20, 2011

A free market of idiots

This has been roundly condemned, as it should be, and it's brought a lot of attention to the nature of British media, also as it should be. Those on the left are trying mightily to attach the scandal to Rupert Murdoch, head of News Corp and owner of News of the World (and of course Fox News here in the US). He's, of course, denying any knowledge of these actions.

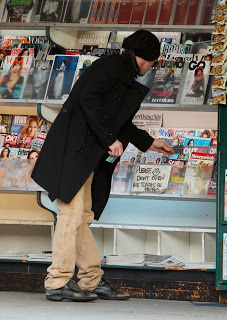

But I don't think Murdoch is utlimately to blame. I think the blame lies here:

Let me be clear: it's not the magazines. It's the person buying them.

Murdoch and his kind do nothing more than obey the first rule of business: give the people what they want. From gossip to innuendo to outright lies, his various media outlets have one thing in common: success. If nobody cared about celebrities, he wouldn't be in the gossip business. If people turned off news that was repeatedly shown to be biased, and with occasional outright fabrications, his news shows would either straighten up or go dark. And if there wasn't a ravenous appetite for sordid details, the phone of a dead girl would not have been hacked.

Every person who buys a magazine with a Kardashian on the cover, or watches the Octomom on TV, or reads Perez Hilton online is as responsible, if not more so, than Rupert Murdoch for the state of media and so-called "news." These consumers have created the environment that promises economic rewards for hacking the phone of a dead girl. The defense is that these magazines are "harmless," that celebrity gossip is "just for fun," but now we've learned that "fun" might extend to the private e-mails, voice mails and medical records of 9/11 families (the FBI is investigating that). Is that "harmless?" Because once you've exhausted celebrity culture (and please, God, I hope we're close), the only things left are private citizens with the bad luck to suffer public tragedy. And that could be any of us. Our worst nightmare could be marketed as "just for fun."

So, let me be plain: supporting this crap with your money and time makes you the problem, not the people who produce it. Stop buying it, and they'll go away. That's how an intelligent free market works. But a free market of idiots leads to this:

July 18, 2011

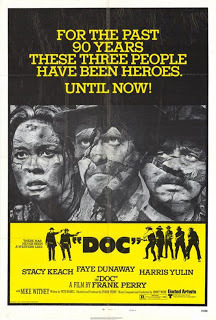

Review: the anti-western Doc

But it ain't nothing compared to the demythologizing in Frank Perry's 1971 film, Doc. Even the poster brags about the tear-down:

Stacy Keach plays Doc Holliday, former dentist and current tubercular gambler, drifting across Arizona to join his friend Earp in Tombstone. Earp is played by Harris Yulin, a ubiquitous character actor who you'll instantly recognize even if the name doesn't register (he even played a Cardassian in Deep Space Nine). Also co-starring is Faye Dunaway as Kate Elder, aka "Big Nose" Kate, Doc's mistress.

With Doc as the central character, we're given the legend from the side. Earp may be the marshall, but he recognizes that in Tombstone, it's the sheriff who runs things. He runs for that office, and makes a deal with the Clanton gang to turn over one of their own at the appropriate time to secure Earp's victory. This view of Earp as not just a brutal man but a corrupt one leaves Costner's arrogant misanthrope in the dust. Doc is Earp's friend, but when he realizes what Earp's done he's caught in a quandary. How that resolves is one of the most cynical depictions of human nature I've seen; it makes Glengarry Glen Ross look like Amelie.

Stacy Keach and Faye Dunaway.

But unlike the Costner film, which seems to think Earp is still deserving of heroic status even after he's shown to be pretty much a total prick, Doc earns its cynicism. Doc is a flawed man who sees himself honestly, and allows himself a brief respite of thinking his life might be salvageable despite his tuberculosis. When he realizes it isn't, he goes with the flow and accepts his fate. The story takes place in a Western world that goes Sergio Leone one better: everyone is dirty and dusty, and at times you can almost smell their unwashed bodies. And the music, by songwriter Jimmy Webb ("MacArthur Park") is low-key and based in period sounds; there's no Elmer Bernstein flourish here.

Harris Yulin as Wyatt Earp.

Doc isn't a feel-good Western, for sure, nor a flawless one: many scenes seem cut too early, as if they needed another few moments to play out. But Keach's performance is so open and minimal that it draws you in, and Yulin's take on Earp never fails to surprise. If you're a fan of Westerns, or just of familiar tales told in new ways, I highly recommend it.