Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 32

September 19, 2011

Reading in public: learn from my fails

I've attended a lot of readings, and been on both sides of the podium. It can be nerve-wracking to look out at the crowd; it can be ennervating sitting in that crowd and realizing you're in for a dire presentation. I make no claim to being a "good" public reader, but I have learned some things from both reading and listening that might help the next new author/reader avoid my mistakes. Here, then, are my tips on reading your book in public.

Me at a recent reading. I appear quite lost without a podium.

6) Practice. It's a basic, but I think a lot of authors skip it. Sure, they're your own words, but the rhythms of speech are different from those of reading in your head. It's embarrassing to stumble over something you've written, then look back at it and realize even you don't know what the hell you were trying to say.

5) Don't be afraid to edit your own text. As I said above, reading aloud is different. Sometimes modifiers are unnecessary, since your tone and inflection do the job. So if you wrote, "'The hell you say,' he said angrily," you can eliminate the attribution and do the job with tone of voice. it makes things go faster, and believe me, that's always a benefit.

4) Don't read sex scenes. Sure, you may have an all-adult audience, but even then, everyone in that crowd will have a different idea of "sexy," and you probably don't want to discover just how far outside the mainstream your own ideas may be. The same goes for excessive violence or strong language. You'll never sell a book to someone who's been embarrassed at your reading.

3) If it takes more than three sentences to set up your excerpt, it's too obscure. It's death to spend ten minutes trying to explain your world, your societies and your characters, all because you've decided that a scene from the middle of the book is the only possible thing you can read. Remember, if you bore your audience, they'll never buy your book.

2) Read the first chapter. Sure, you may be proudest of the scene two-thirds of the way through, but the first chapter is (or should be) the one that makes readers want to get to that great scene. It should also pull them in to your world, your characters and your situations. In fact, unless you're reading to an audience that's already heard your first chapter, this should be your standard modus operandi.

The only thing that supercedes rule #2, and even then not always, is rule #1:

1) Read the funny parts. Getting a crowd to laugh together means they'll all remember your book as something they enjoyed. Ideally your first chapter will have a couple of good laughs, which to me is the perfect reading source. If not, if there are any jokes, find them and use them.

I'm open to additional rules from people who have attended readings; leave them in the comments below. And in my next post I'll have some suggestions from other authors.

September 18, 2011

The full book trailer for "THE HUM AND THE SHIVER"

September 12, 2011

New blog! New website!

Who are the Melungeons, and where did they come from?

My upcoming novel The Hum and the Shiver posits a secret, isolated race of people living in the middle of modern-day Appalachia. They have a distinctive physical look, very different from those around them. They hide in plain sight, using the standard Southern tactics of politeness and misdirection to deflect queries about themselves. I call them the Tufa. They're entirely, totally fictional.

But they're inspired by a real story, a real mystery and a real group of people: the Melungeons.

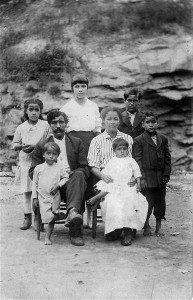

The Goins family, circa 1928

There's lots of information online about the Melungeons, so I won't bore you with recapping it in detail; the Wikipedia entry lists many related articles that can answer most questions. Instead I'll share what drew me to them. First it was the simple idea that there could be a group of ethnically distinct people living in modern-day East Tennessee. I'm from Tennessee, and I'd never really heard of them until I was grown and had moved away. A lot of that is due to the racial attitudes of the region: overwhelming settled by the Scotch-Irish, and therefore Caucasian, they viewed the dark-haired, swarthy Melungeons as something other than white, which meant they could not vote or own property, even though they were technically "free."

Also, the legends say that when the first of those Scotch-Irish settlers arrived in Appalachia, the Melungeons were already there. This has been challenged by scholars, but for me the power of the idea was secondary to its literal truth. What if it was true? And if it was, then it goes back to the crucial question about Melungeon ancestry: where did they come from? Heck, for that matter, where did the word "Melungeon" come from? There are various speculations, but no proof.

When I got ready to write my story, I knew immediately I wouldn't try to tell the actual Melungeon story. These are, after all, real people who deserve respect. So I took the elements of their legends that spoke to me and invented my own group of people, the Tufa. Like the Melungeons, they live in the mountains of East Tennessee, and were already there when the first European settlers arrived five hundred years earlier. They have a particular physical appearance, and keep to themselves. But because I invented them, I could also invent their origin, something the real Melungeons are still trying to discover.

And what is that origin? Well, to find out, you'll have to read The Hum and the Shiver. You can preview chapter one by visiting here.

September 5, 2011

The Strange Case of the Inadvertent Exorcism

It's no secret that The Sword-Edged Blonde, the first Eddie LaCrosse novel (and my first novel, period), was inspired in part by the Fleetwood Mac song "Rhiannon." I was twelve when it was released, and since I grew up in the era of rock-oriented FM radio I heard it a lot. And it never failed to captivate me. Remember, this was the time of John Denver, the Captain and Tennille and the first stirrings of disco-era Bee Gees. In that crowd, "Rhiannon" was the perfect storm of things to get a teenage nerd's attention: a mysterious lyric (based on Celtic lore, about which a small-town Southern boy like me was totally ignorant), a guitar lick that sounded like an invocation to sorcery, and a singer who embodied (again, to a small-town Southern boy) California sophistication, sexuality and, okay, magic. If ever a song cast a legitimate spell, this one did on me.

For over twenty years, as I wrestled various drafts of the novel and searched for just the right way to tell the story, this song was my touchstone. I might have ignored the manuscript for months, but if "Rhiannon" came on the radio it caused a whole new surge of inspiration. In the song, in Stevie Nicks' voice and Lindsey Buckingham's haunting arrangement, I heard the magic I sought. I wanted my book, in other words, to feel like the song.

Stevie Nicks' painting of Rhiannon.

Stevie Nicks' painting of Rhiannon.That lasted a lot longer than it probably should have. As I've learned since then, every story should have its own unique feel, regardless of its inspiration. And truthfully, once I made the decision to stop trying to write the next Tolkein or Terry Brooks epic, that unique feel presented itself. Discovering Eddie LaCrosse's voice took me away from all the influences that had overwhelmed me, and while there are echoes of them (the noir writers I admire, for instance, loom large over this first book in particular), there's also something unique. For better or worse, good or bad, I feel it doesn't sound like anyone else's writing.

So that's a happy ending, right?

Well, sort of. But there's a trope in fantasy that says all magic has a cost. And apparently the magic that let me finally get the book right also cost me my fascination with the song. Because now when I hear it, I feel…nothing.

I still like the song, Fleetwood Mac and Stevie Nicks. My iPod bears this out. But the act of completing The Sword-Edged Blonde inadvertently exorcised the sense of magic that always overwhelmed me when I heard it. Perhaps this was a good thing; but I can't help thinking the loss of any magic should, at some level, be mourned.

So RIP, "Rhiannon." You have become, finally, a song taken by the wind.

August 29, 2011

Meg Coburn, the forgotten action heroine

I love action heroines. I've even put one in my next Eddie LaCrosse novel, Wake of the Bloody Angel. But my standards require, if not strict adherence, at least lip service to the laws of the natural world. That negates the whole concept of the the "ass-kicking sprite," wherein a tiny female character suddenly has the ability to overpower people (usually men) three times her size. No, my idea of an action heroine is someone like Xena, who has the physical size and strength to really do battle. And of course, the gold standard is Ellen Ripley in Aliens. She has no super, or supernatural, powers; she's merely tough, resourceful, determined and smart.

Which brings me to the great forgotten action heroine: Meg Coburn. Feel free to insert your own variation of, "Who?"

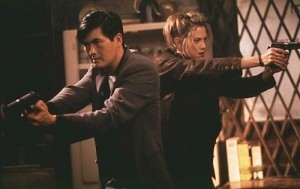

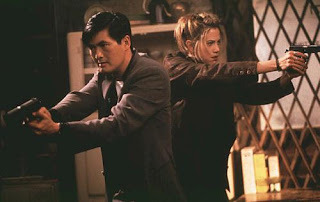

Meg Coburn, played by Mira Sorvino, was the heroine of Antoine Fuqua's 1998 film The Replacement Killers. Notable as the American film debut for Hong Kong star Chow Yun-Fat, it's a fairly simple story of hired killer John Lee (Chow), who decides he has a conscience after all. Meg Coburn is a forger he hires to make a new passport so he can return to China and protect his family. Unfortunately the bad guys intervene, putting Lee and Meg on the run together.

Two moments cement her appeal for me. One is visual: during the shootout in her first scene, she and Chow Yun-Fat arrive in the same room and drop into the same pose, only aiming in opposite directions. The image says it all: it's the mutual competence of equals. And in an action movie, if you're as competent as Chow Yun-Fat, you're doing all right.

The second occurs later, when John forces Meg at gunpoint to accompany him. She gives him a look that could freeze magma and says calmly, "Okay, if that's the way you want to play it. But when the gun is in my hand, we're going to have this conversation again."

There's a ton of other things that make Meg cool, but in some ways the things she doesn't do are more interesting. She never panics. She may yell, but she never once screams. She never stops trying to resolve the immediate situation. Yes, she's feminine and sexy, but it's incidental; there's only one fleeting shot I'd describe as actual Michael Bay-style pandering.

If you decide to see the film, seek out the "extended cut" DVD. Since it was made in 1998, when Hong Kong was about to revert to Chinese control, a crucial subplot was minimized in the theatrical release to avoid offending China and losing Chow Yun-Fat's hometown market. It's been restored here, and it fleshes out the motivations in a pretty substantial way.

It's obvious that we, the public, want different things from our heroines than from our heroes. It's why Supergirl dresses like a cheerleader, after all. But occasionally, amongst the pantings and leerings of the Bays and Favreaus, a real person slips through. Mira Sorvino's Meg Coburn was one of those. It's a shame more people didn't notice.

Meg Coburn, the forgotten action heroine

I love action heroines. I've even put one in my next Eddie LaCrosse novel, Wake of the Bloody Angel. But my standards require, if not strict adherence, at least lip service to the laws of the natural world. That negates the whole concept of the "ass-kicking sprite," wherein a tiny female character suddenly has the ability to overpower people (usually men) three times her size. No, my idea of an action heroine is someone like Xena, who has the physical size and strength to really do battle. And of course, the gold standard is Ellen Ripley in Aliens. She has no super, or supernatural, powers; she's merely tough, resourceful, determined and smart.

Which brings me to the great forgotten action heroine: Meg Coburn. Feel free to insert your own variation of, "Who?"

Meg Coburn, played by Mira Sorvino, was the heroine of Antoine Fuqua's 1998 film The Replacement Killers. Notable as the American film debut for Hong Kong star Chow Yun-Fat, it's a fairly simple story of hired killer John Lee (Chow), who decides he has a conscience after all. Meg Coburn is a forger he hires to make a new passport so he can return to China and protect his family. Unfortunately the bad guys intervene, putting Lee and Meg on the run together.

Two moments cement her appeal for me. One is visual: during the shootout in her first scene, she and Chow Yun-Fat arrive in the same room and drop into the same pose, only aiming in opposite directions. The image says it all: it's the mutual competence of equals. And in an action movie, if you're as competent as Chow Yun-Fat, you're doing all right.

The second occurs later, when John forces Meg at gunpoint to accompany him. She gives him a look that could freeze magma and says calmly, "Okay, if that's the way you want to play it. But when the gun is in my hand, we're going to have this conversation again."

There's a ton of other things that make Meg cool, but in some ways the things she doesn't do are more interesting. She never panics. She may yell, but she never once screams. She never stops trying to resolve the immediate situation. Yes, she's feminine and sexy, but it's incidental; there's only one fleeting shot I'd describe as actual Michael Bay-style pandering.

If you decide to see the film, seek out the "extended cut" DVD. Since it was made in 1998, when Hong Kong was about to revert to Chinese control, a crucial subplot was minimized in the theatrical release to avoid offending China and losing Chow Yun-Fat's hometown market. It's been restored here, and it fleshes out the motivations in a pretty substantial way.

It's obvious that we, the public, want different things from our heroines than from our heroes. It's why Supergirl dresses like a cheerleader, after all. But occasionally, amongst the pantings and leerings of the Bays, Favreaus and Snyders, a real person slips through. Mira Sorvino's Meg Coburn was one of those. It's a shame more people didn't notice.

August 22, 2011

Love, Revenge and Conan: What's My Motivation?

So there's a new Conan movie. And, if the previews are any indication, Conan spends the movie on a quest for revenge against the villain(s) who destroyed his village and murdered his family.

I won't go into how many ways this deviates from the original Robert E. Howard character (short answer: a lot). Instead, it got me thinking about screenwriters and how they think.

Consider the idea of "motivation." In movies, heroes are usually motivated by either love or revenge. And they must have a definite, solid, entirely personal reason for doing anything. I first became conscious of this trope watching The Skeleton Key, eighty percent of a great horror movie. Caroline, played by Kate Hudson, talks about how she became a geriatrics nurse after watching an elderly relative slowly die from Alzheimer's.

"Ah-HA! My motivation! Now I can act!"

Really? So she couldn't be a person who looked at possible careers and chose one that sounded good, or wanted to have a job with security, or any of the reasons most of us choose our jobs? No, there had to be a hyper-dramatic, entirely personal reason so that the audience will "sympathize" with her.

Giving Caroline such a background smacks of a "Screenwriting for Dummies" lesson. Sure, characters need motivation. But screenwriters seem unable to accept that "earning a paycheck," "providing for my family" or most crucially "the satisfaction of a job well done" are acceptable motivations. If the line "this time it's personal" doesn't apply, then it isn't valid.

Except that it is.

Here are two examples from the work of Oscar-winning director/screenwriter William Friedkin. In his 1986 film To Live and Die in L.A., FBI agent Richard Chance (CSI's William Petersen) sets out to bring down villain Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe) after Masters kills his partner. He even blatantly states, "I'm gonna bag Masters, and I don't give a shit how I do it." It's a textbook--well, a screenwriting textbook--character motivation. This time it's personal, and it encompasses both love (of the bromance kind) and revenge. It keeps an otherwise excellent movie from being truly great.

Conversely, in Friedkin's 1971 film The French Connection, New York cop Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) stays tenaciously on the villain's tail because, simply, it's his job. He needs no ulterior motive, nothing that says "this time it's personal." Through the course of the story it becomes personal, but only because the villain's success reflects badly on his professionalism. His ego is tied to his job, and he simply can't let the bad guys win. There's no hint that a childhood trauma caused this, or that a gangster (or Frenchman) once killed his family, or any sort of trite justification. It's realistic, and it's one of the elements that helps make the film a classic.

There are many useful things novelists can learn from screenwriters: get to the point, keep the action moving, craft witty dialogue and so forth. But this is one lesson they should skip. So make sure that you take away the right lessons, and stay grounded in reality where there are many other motivations besides love and revenge.

But....

As I read over the above, I realized my perspective is entirely one-sided. So for another point of view, I asked writer and USC film graduate Melissa Olson to comment on what I'd written so far. She responded:

"When I was at USC, nobody dreamed of being the next Michael Bay (well, maybe in the directing track(:). Everyone dreamed of telling the story they wanted to tell, to make the statement they wanted to make. But once you get out of school, the film industry is a tough business.

"Screenwriting is complicated, and in many ways it's much more restrictive than novels. Maybe the screenwriters of Conan (there were three) didn't want the movie to be about motivation; they wanted to get that out of the way and tell a different story. Shortcuts aren't terrible things, they're just easy ways out. Sometimes you gotta take one to get to where you want to go."

So there's two sides to this. What do you, the reader/filmgoer, think?

Love, revenge, and Conan: what's my motivation?

So there's a new Conan the Barbarian movie. And, if the previews are any indication, Conan spends the movie on a quest for revenge against the villain(s) who destroyed his village and murdered his family.

I won't go into how many ways this deviates from the original Robert E. Howard character (short answer: a lot). Instead, it got me thinking about screenwriters and how they think.

Consider the idea of "motivation." In movies, heroes are usually motivated by either love or revenge. And they must have a definite, solid, entirely personal reason for doing anything. I first became conscious of this trope watching The Skeleton Key, eighty percent of a great horror movie. Caroline, played by Kate Hudson, talks about how she became a geriatrics nurse after watching an elderly relative slowly die from Alzheimer's.

Really? So she couldn't be a person who looked at possible careers and chose one that sounded good, or wanted to have a job with security, or any of the reasons most of us choose our jobs? No, there had to be a hyper-dramatic, entirely personal reason so that the audience will "sympathize" with her.

Giving Caroline such a background smacks of a "Screenwriting for Dummies" lesson. Sure, characters need motivation. But screenwriters seem unable to accept that "earning a paycheck," "providing for my family" or most crucially "the satisfaction of a job well done" are acceptable motivations. If the line "this time it's personal" doesn't apply, then it isn't valid.

Except that it is.

Here are two examples from the work of Oscar-winning director/screenwriter William Friedkin. In his 1986 film To Live and Die in L.A., FBI agent Richard Chance (William Petersen) sets out to bring down villain Rick Masters (Willem Dafoe) after Masters kills his partner. He even blatantly states, "I'm gonna bag Masters, and I don't give a shit how I do it." It's a textbook–well, a screenwriting textbook–character motivation. This time it's personal, and it encompasses both love (of the bromance kind) and revenge. It keeps an otherwise excellent movie from being truly great.

Conversely, in Friedkin's 1971 film The French Connection, New York cop Popeye Doyle (Gene Hackman) stays tenaciously on the villain's tail because, simply, it's his job. He needs no ulterior motive, nothing that says "this time it's personal." Through the course of the story it becomes personal, but only because the villain's success reflects badly on his professionalism. His ego is tied to his job, and he simply can't let the bad guys win. There's no hint that a childhood trauma caused this, or that a gangster (or Frenchman) once killed his family, or any sort of trite justification. It's realistic, and it's one of the elements that helps make the film a classic.

There are many useful things novelists can learn from screenwriters: get to the point, keep the action moving, craft witty dialogue and so forth. But this is one lesson they should skip. So make sure that you take away the right lessons, and stay grounded in reality where there are many other motivations besides love and revenge.

But….

As I read over the above, I realized my perspective is entirely one-sided. So for another point of view, I asked writer and USC film graduate Melissa Olson to comment on what I'd written so far. She responded:

"When I was at USC, nobody dreamed of being the next Michael Bay (well, maybe in the directing track(:). Everyone dreamed of telling the story they wanted to tell, to make the statement they wanted to make. But once you get out of school, the film industry is a tough business.

"Screenwriting is complicated, and in many ways it's much more restrictive than novels. Maybe the screenwriters of Conan (there were three) didn't want the movie to be about motivation; they wanted to get that out of the way and tell a different story. Shortcuts aren't terrible things, they're just easy ways out. Sometimes you gotta take one to get to where you want to go."

So there's two sides to this. What do you, the reader/filmgoer, think?