Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 34

July 13, 2011

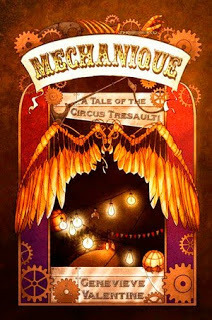

Interview: Genevieve Valentine, author of Mechanique

Recently I reviewed the debut novel by Genevieve Valentine, Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresaulti. I thought it a brilliant and intriguing book, and as a writer, I wondered about the thought process behind some of the concepts. Genevieve was kind enough to answer some questions for me.

The bones (in the story, circus aerialists have their human bones replaces with light, hollow copper one) represent different things to each character who receives them. What inspired them, and what did they represent for you, the author?

Appropriately enough, bird skeletons were a large part of the influence on the bones. I was looking them up for something unrelated, but the physiology was really interesting and stuck with me as I started writing about what exactly made the performers in the Circus Tresaulti so different. For me, the bones were always a tangible symbol of the sacrifices you make for something you love, though the self-destructive aspect of it often goes hand-in-hand, depending on the character.

The narrative jumps among several voices and points of view. Why did you choose that form?

When I sat down to begin I just started writing, and the scenes I wanted to get down first came first, in the perspective I thought made the most sense. By the time I had the breathing space to sit back and worry if it was going to work, I loved how it was coming together too much to think about stopping.

The story doesn't have a specific setting, either geographically or in time. Why did you decide on that?

I approached it with the idea that the deep aftermath of a war takes on this air of inevitability and surreality, as if it both defined and took place outside of the world now. With a war as big as the one that's implied here, that devastates natural resources and completely shifts the practice of government, old nations and eras slowly cease to matter. It doesn't help that the Circus operates in this landscape as they themselves are a bit unstuck in time by the magic that holds the Circus together.

How well did the artwork by Kiri Moth capture your sense of the story?

SO WELL. Sorry for the caps, but it's awesome. The cover alone is so detailed and evocative that no one could ask for more, but for me, some of the interior art pieces truly hit home. My two favorites are probably the griffin, which is so perfect it's become an emblem for the Circus in earnest, and Elena on the trapeze. The grace and introspection and loneliness of that moment is exactly how I had pictured it when I was writing, and seeing the recreation in my inbox the first time, I clutched my pearls like a dowager.

Published on July 13, 2011 02:27

July 11, 2011

Review: Mechanique by Genevieve Valentine

Bruce Springsteen says his classic song "Born to Run" is about people looking for "connection." The great crime novelist Andrew Vachss fills his stories with people forming "families of choice" to retain their humanity against the brutal outside world. And in the same vein, the heart of Genevieve Valentine's Mechanique: A Tale of the Circus Tresaulti shows how the bonds of family can form between and among people who otherwise have nothing in common.

If you have to give it a genre, I suppose Mechanique counts as steampunk. Or fantasy. Some aspects verge on science fiction. But it plays with these conventions as much as it does with narrative form. It's not set in the past, like steampunk, and it's not about technology, like science fiction. Its landscape is post-apocalyptic, but with no set time frame (or even confirmation that it's actually set on Earth). And there is a sense of magic to what happens, but it's so grounded, so organic and mundane, that it's as far from the standard tropes as you can get. None of this really matters, though, because ultimately it's about people-building, not world-building.

Via a fractured narrative point of view, we learn that the circus, led by the enigmatic woman known only as Boss, features performers that are part metal, with hollow copper bones to make their feats that much more astounding. One even features the enormous metal wings shown on the cover, but he's dead when the story begins. Which doesn't mean he doesn't figure in things, because Valentine jumps back and forth, changing point of view and time frame whenever it suits her. The story is most often told by Little George, a boy of indeterminate age who works as Boss' go-fer. Through him we learn the complexities of the Tresaulti personalities, and a bit about how some of them came to join the circus. It's a real tribute to Valentine's skill that this is never confusing or disorienting.

If there's a criticism to be made, it's that the plot takes so long to get going, it almost seems like an intrusion. For its first half Mechanique is a brilliant high wire act of a mood piece; the events of the second half jar only because of their relative normality. But that's minor, and ultimately the second half wouldn't work without the emotional investment of the first.

I've known Genevieve for several years now, mostly as a delightful raconteur at conventions and a deliciously snarky columnist. I'd read some of her short fiction, but nothing prepared me for this, not even hearing her read the first few chapters at last year's World Fantasy Convention. She's created a unique world here, and made a brilliant debut as a novelist.

Come back Wednesday for an interview with Genevieve Valentine.

Published on July 11, 2011 02:36

July 10, 2011

Guest blogging on why I'm no longer a Star Wars fan

At the Borders SciFi blog, I talk about why I'm no longer a fan of Star Wars. It has nothing to do with who shot first. Read about it here.

Published on July 10, 2011 16:31

July 6, 2011

Guest blogging on the (re)claiming of Lois Lane

I'm guest blogging at SF Signal about Lois Lane, and how she changed between the original cut of Superman II and the 2006 restored "Donner Cut." Stop by and leave a comment!

Published on July 06, 2011 13:01

July 4, 2011

Look back in chagrin

Recently I've been revising an old manuscript that I originally wrote over a decade ago, and haven't touched in at least seven years. It's an interesting window into the past of my own creative process, and some lessons I've since learned are vividly displayed in all their teeth-gnashing glory. Here are some examples.

1) A little description goes a long way. I described the physical settings in great detail, thinking at the time that the action wouldn't work without it. I try to always make my action scenes use the specific geography I've set up, so that the reader gets the sense that these events could happen nowhere else. I now know that back then, I seriously underestimated the reader's ability to comprehend. For example, I had this as a description of a creek:

"The creek occupied an open ribbon of ground fifty feet wide, and the grass beyond it grew high enough to hide anything."

I thought that readers needed to know that the width of open ground would accommodate the events about to occur. However, in revision I realized this was didactic overkill. Whatever image of a "creek" the reader conjures will work quite well, and has the virtue of getting the reader to contribute to the story's reality.

I also tended to give exact measurements when they weren't necessary. For example, "[it] landed hard on its belly ten yards away." In context of the scene, knowing the precise distance is pedantic and unnecessary.

2) There's a fine line between ambiguity and confusing lack of information, and I often have trouble seeing this line until someone points it out to me. In this story, the plot was set in motion by a man wandering out of the desert and promptly dropping dead. We never found out who he was, where he came from, or why he carried the McGuffin he brought. In re-reading I realized this was a huge dangling plot point that might--and probably should--annoy the reader. So while I liked the ambiguity and wanted to keep as much as possible, I filled in some more detail and implication, so there's at least some sort of explanation.

3) Elmore Leonard, a man who should know, advises, "Never use a verb other than 'said' to carry dialogue." I had clearly not grasped that concept. If the tone of the dialogue isn't clear from the dialogue itself, then in most cases you need to back up and rethink the words. Certainly I did.

4) My chapters have gotten shorter. The first five chapters of this book averaged 17-18 manuscript pages, while my more recent ones are between 13-15. This is an observation, not a value judgment, since in one sense a chapter is as long as it needs to be. But evidently mine need to be shorter than they used to.

And finally,

5) The chapters may be longer, but this book was short. Really short. 350 manuscript pages, when my average for the Eddie LaCrosse series is between 400-420 (and even that's short compared to most fantasy novels). As I revise, I've found places to legitimately add more detail and incident, but I internalized too much journalism to tolerate any padding. And that's another important lesson: like a chapter, a story is as long as it is. Some stories might need multiple volumes of a thousand pages each; then again, some might just take 400 or so pages. Maybe less.

Yes, a lot of these lessons caused me to wince, clench my teeth and look away in both disgust and horror. The urge to think, "I can't believe I wrote something so bad" is pretty strong. But it's also incorrect. I wrote this story the best that I could at the time. I improve with each story I write, with each comment and suggestion I get from my editor, and with each book I read. The process doesn't end. So if you're an aspiring writer out there, and you resurrect an old manuscript that makes you want to give up writing forever, remember two things: a) it was the best you could do at the time, and b) you're better now.

And that should always be true.

1) A little description goes a long way. I described the physical settings in great detail, thinking at the time that the action wouldn't work without it. I try to always make my action scenes use the specific geography I've set up, so that the reader gets the sense that these events could happen nowhere else. I now know that back then, I seriously underestimated the reader's ability to comprehend. For example, I had this as a description of a creek:

"The creek occupied an open ribbon of ground fifty feet wide, and the grass beyond it grew high enough to hide anything."

I thought that readers needed to know that the width of open ground would accommodate the events about to occur. However, in revision I realized this was didactic overkill. Whatever image of a "creek" the reader conjures will work quite well, and has the virtue of getting the reader to contribute to the story's reality.

I also tended to give exact measurements when they weren't necessary. For example, "[it] landed hard on its belly ten yards away." In context of the scene, knowing the precise distance is pedantic and unnecessary.

2) There's a fine line between ambiguity and confusing lack of information, and I often have trouble seeing this line until someone points it out to me. In this story, the plot was set in motion by a man wandering out of the desert and promptly dropping dead. We never found out who he was, where he came from, or why he carried the McGuffin he brought. In re-reading I realized this was a huge dangling plot point that might--and probably should--annoy the reader. So while I liked the ambiguity and wanted to keep as much as possible, I filled in some more detail and implication, so there's at least some sort of explanation.

3) Elmore Leonard, a man who should know, advises, "Never use a verb other than 'said' to carry dialogue." I had clearly not grasped that concept. If the tone of the dialogue isn't clear from the dialogue itself, then in most cases you need to back up and rethink the words. Certainly I did.

4) My chapters have gotten shorter. The first five chapters of this book averaged 17-18 manuscript pages, while my more recent ones are between 13-15. This is an observation, not a value judgment, since in one sense a chapter is as long as it needs to be. But evidently mine need to be shorter than they used to.

And finally,

5) The chapters may be longer, but this book was short. Really short. 350 manuscript pages, when my average for the Eddie LaCrosse series is between 400-420 (and even that's short compared to most fantasy novels). As I revise, I've found places to legitimately add more detail and incident, but I internalized too much journalism to tolerate any padding. And that's another important lesson: like a chapter, a story is as long as it is. Some stories might need multiple volumes of a thousand pages each; then again, some might just take 400 or so pages. Maybe less.

Yes, a lot of these lessons caused me to wince, clench my teeth and look away in both disgust and horror. The urge to think, "I can't believe I wrote something so bad" is pretty strong. But it's also incorrect. I wrote this story the best that I could at the time. I improve with each story I write, with each comment and suggestion I get from my editor, and with each book I read. The process doesn't end. So if you're an aspiring writer out there, and you resurrect an old manuscript that makes you want to give up writing forever, remember two things: a) it was the best you could do at the time, and b) you're better now.

And that should always be true.

Published on July 04, 2011 05:43

June 29, 2011

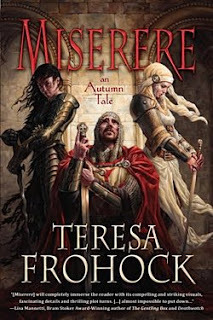

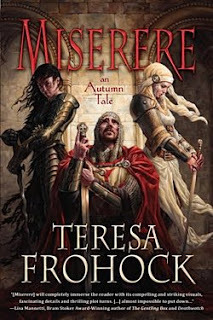

Interview with Teresa Frohock, author of Miserere

Teresa Frohock is both a friend and the author of Miserere: an Autumn Tale, a book I enjoyed so much that I gave her the following blurb:

"Miserere is about redemption, and the triumph of our best impulses over our worst. It's also about swords, monsters, chases, ghosts, magic, court intrigues and battles to the death. It's also (and this is the important part) really, really good."

You can read my full review here.

Teresa graciously agreed to answer some questions for me about the book.

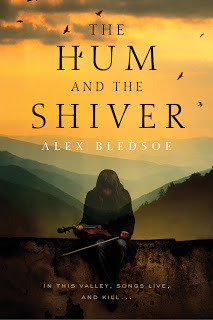

You and I have both recently written books that include people of genuine, true religious faith (my book is The Hum and the Shiver, out this fall). The pitfalls of this are enormous: the danger of sanctimoniousness, of preachiness (literal and figurative), of simply alienating readers who don't share whatever faith the characters embody. How much did you worry about this, and how did you overcome it?

Thanks so much for having me here, Alex, I really appreciate the opportunity to talk about some of this.

Truth be told, I'm still worried about some of those things. Although I think people who read speculative fiction are open-minded and much more amenable to experimentation than other genres, I still worry that some may suffer contempt prior to investigation. I hope not.

It helps that I have no agenda here. I'm not out to push a viewpoint, Christian or otherwise. I just wanted to tell a story, and as I constructed Woerld, I realized the focus would be on Lucian, who happened to belong to the Christian bastion. From that point forward, I had to educate myself about Christianity and I was really surprised by the facts I found.

The version of Christianity that I present on Woerld is gleaned not just from Biblical sources, but also from the Pseudepigrapha and Apocrypa. I wanted to see what Christianity might have been like before the Schism of 1054 when Rome split from the Byzantine Church. I approached all the religions on Woerld strictly from a scholarly angle at first, then I eased the spiritual elements inherent to the practices of the religion into the story.

I focused entirely on the growth of the individual character and not the dogma of the religion. And that was hard, showing how the adherents struggle with their faith from personal viewpoints. When we speak of Muslims, Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, we tend to think in terms of groups, not individuals. I wanted to put the focus on the individual and show that

personal growth doesn't come from automatically joining a group, but comes through the internal work of the individual.

If you read most religious texts closely, they emphasize a personal contact with a higher power, not group-think. So I did very much what you've done with Reverend Craig in The Hum and the Shiver—I simply had Lucian live his life in accordance with the dictates of his beliefs. I've always loved Emerson and Thoreau's writings and their emphasis on the individual's responsibility to contact the divine within and bring that light into the world through action. That is a concept inherent to all religions and I wanted to illustrate that philosophy in Miserere.

You incorporate a young woman, Lindsay, who must learn both to be a warrior (a common fantasy trope) and to truly believe in God (not so common). What did she represent for you?

Lindsay represents our twenty-first century's society secular thinking about religion, our preconceptions and our misconceptions. Her exposure to religion comes primarily through the media, meaning she understands the various religions through the extremes of the worst possible examples of the adherents: politicians who mouth their version of Christianity while they actively engage in immoral behavior; a Catholic Church hiding child-molesting priests; jihadists that believe their way to paradise is paved with the bodies they leave behind; Hindus and Muslims and Christians and Jews constantly fighting one another either in rhetoric or with guns.

This is what Lindsay is exposed to day after day, then she is taken to the obligatory church service, plunked in a pew, and told God is love. Needless to say, she's a tad cynical over the whole thing. Kind of like the rest of us.

So I like having her as the voice of the reader, to question Lucian and the adults in Woerld about how things work. That way I can gently ease my readers into Woerld yet not make the picture too rosy. It's not. There are serious conflicts among the bastions and the governments in Woerld—it was never my intent to present a Utopian society.

Children aren't afraid to question the status quo, and they see things very clearly, more clearly than adults want to admit. Lindsay is the perfect lens to view Woerld and its imperfections.

Your novel is definitely a fantasy, and many fantasies create their own religions. You chose to use actual existing world religions. What was your thought process behind that?

I thought about Tolkien and Lewis and wondered what The Lord of the Rings would have looked like if Tolkien had written it as a Catholic story instead of embedding the religious tenets beneath Middle Earth's mythology, or what Narnia would have looked like if, instead of a lion, Aslan was the Christ. Not being as much of a fan of Tolkien as I am of Lewis, I really started reading Lewis' works; he had a talent for rooting out the spirituality of Christianity and getting to the essence of its beliefs without sanctimony.

I checked out some other current fantasy titles that used fallen angels, and while they addressed the fallen part of the situation, very few showed it from a Christian angle. I think God's Demon by Wayne Barlowe was the closest novel to presenting hell from a Christian viewpoint, and I love what Barlowe did with that story. The language he used, the characterization, and his perception of hell as an actual, physical place just knocked me for a loop.

Barlowe took the war in heaven and showed how the fallen angels fought. I've always been fascinated by the war in heaven and often wondered: what if it's still going on? I'm sacrilegious like that.

In the end, I fell in love with the absolute challenge of it. This is my own ego talking now, but I wanted to prove you could write a fantasy with Christians in it without the story becoming insipid or preachy. I began constructing Woerld and realized that all religions have some form of hell or purgatory, so realistically, it wouldn't be just Christians. I mean why would heaven only use a fraction of its forces to combat evil?

So the other religions started seeping in and with that there must be a hierarchy, and the structure of Woerld evolved until it became what it is in Miserere. The more I worked on it, the more detail seeped in, and again, I just loved the challenge of using real religions.

You have a male hero torn between and among a group of women: his sister, his former lover, and his new protégé. Was there a deliberate thought process behind the gender roles for these characters?

I wanted to step outside of a few of the standard fantasy tropes and twist them. The most common trope from the fairy tales of my youth was that of the beautiful princess who was captured by the evil warlord or witch and rescued by a handsome prince. I wanted to turn that trope upside down and show the handsome prince who was captured by the wicked queen and rescued by the beautiful princess. Only in Miserere, the prince takes a real beating from the wicked queen, the beautiful princess is mauled and half-mad, and the wicked queen isn't strung too tight either.

That was my primary thinking, then everything sort of got away from me. Most people are conditioned to see men in one of two roles: protector or aggressor. Lucian sees himself as the protector, even though it is Lindsay and Rachael who end up saving him more often than he saves them. He is determined not to abandon them, though, and that's important, that desire to be a part of someone's life even if it means constraints on his existence.

Nor did I want the women to be perfect. Rachael had her part in her own downfall; Catarina is a grand case of self-will run riot; and Lindsay thinks they're all being horribly unfair to Lucian while she downplays his crimes in her own mind.

When I got the cover art for Miserere (by the wonderful Michael C. Hayes), I just cried, it was better than anything I could have imagined. I had been dreading what an artist's conception of Miserere would be, but more than anything, I feared chain mail bikinis on the women and Lucian standing with Catarina and Rachael kneeling or the women pictured lower in the foreground.

Instead, Michael got exactly what I was doing and busted the tropes with me: they're all standing with their backs to one another; Rachael and Catarina are wearing the armor they would probably choose; Lucian is on his knees between them; and the walls of the Citadel rise behind them. Catarina's face is cunning, Rachael is distrustfully looking at Lucian, and Lucian—my

poor Lucian—looks to Heaven, because when you're trapped between those two women, your only salvation is from above.

Thanks to Teresa Frohock for answering my questions. Miserere: an Autumn Tale is available now from Night Shade Books.

"Miserere is about redemption, and the triumph of our best impulses over our worst. It's also about swords, monsters, chases, ghosts, magic, court intrigues and battles to the death. It's also (and this is the important part) really, really good."

You can read my full review here.

Teresa graciously agreed to answer some questions for me about the book.

You and I have both recently written books that include people of genuine, true religious faith (my book is The Hum and the Shiver, out this fall). The pitfalls of this are enormous: the danger of sanctimoniousness, of preachiness (literal and figurative), of simply alienating readers who don't share whatever faith the characters embody. How much did you worry about this, and how did you overcome it?

Thanks so much for having me here, Alex, I really appreciate the opportunity to talk about some of this.

Truth be told, I'm still worried about some of those things. Although I think people who read speculative fiction are open-minded and much more amenable to experimentation than other genres, I still worry that some may suffer contempt prior to investigation. I hope not.

It helps that I have no agenda here. I'm not out to push a viewpoint, Christian or otherwise. I just wanted to tell a story, and as I constructed Woerld, I realized the focus would be on Lucian, who happened to belong to the Christian bastion. From that point forward, I had to educate myself about Christianity and I was really surprised by the facts I found.

The version of Christianity that I present on Woerld is gleaned not just from Biblical sources, but also from the Pseudepigrapha and Apocrypa. I wanted to see what Christianity might have been like before the Schism of 1054 when Rome split from the Byzantine Church. I approached all the religions on Woerld strictly from a scholarly angle at first, then I eased the spiritual elements inherent to the practices of the religion into the story.

I focused entirely on the growth of the individual character and not the dogma of the religion. And that was hard, showing how the adherents struggle with their faith from personal viewpoints. When we speak of Muslims, Jews, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus, we tend to think in terms of groups, not individuals. I wanted to put the focus on the individual and show that

personal growth doesn't come from automatically joining a group, but comes through the internal work of the individual.

If you read most religious texts closely, they emphasize a personal contact with a higher power, not group-think. So I did very much what you've done with Reverend Craig in The Hum and the Shiver—I simply had Lucian live his life in accordance with the dictates of his beliefs. I've always loved Emerson and Thoreau's writings and their emphasis on the individual's responsibility to contact the divine within and bring that light into the world through action. That is a concept inherent to all religions and I wanted to illustrate that philosophy in Miserere.

You incorporate a young woman, Lindsay, who must learn both to be a warrior (a common fantasy trope) and to truly believe in God (not so common). What did she represent for you?

Lindsay represents our twenty-first century's society secular thinking about religion, our preconceptions and our misconceptions. Her exposure to religion comes primarily through the media, meaning she understands the various religions through the extremes of the worst possible examples of the adherents: politicians who mouth their version of Christianity while they actively engage in immoral behavior; a Catholic Church hiding child-molesting priests; jihadists that believe their way to paradise is paved with the bodies they leave behind; Hindus and Muslims and Christians and Jews constantly fighting one another either in rhetoric or with guns.

This is what Lindsay is exposed to day after day, then she is taken to the obligatory church service, plunked in a pew, and told God is love. Needless to say, she's a tad cynical over the whole thing. Kind of like the rest of us.

So I like having her as the voice of the reader, to question Lucian and the adults in Woerld about how things work. That way I can gently ease my readers into Woerld yet not make the picture too rosy. It's not. There are serious conflicts among the bastions and the governments in Woerld—it was never my intent to present a Utopian society.

Children aren't afraid to question the status quo, and they see things very clearly, more clearly than adults want to admit. Lindsay is the perfect lens to view Woerld and its imperfections.

Your novel is definitely a fantasy, and many fantasies create their own religions. You chose to use actual existing world religions. What was your thought process behind that?

I thought about Tolkien and Lewis and wondered what The Lord of the Rings would have looked like if Tolkien had written it as a Catholic story instead of embedding the religious tenets beneath Middle Earth's mythology, or what Narnia would have looked like if, instead of a lion, Aslan was the Christ. Not being as much of a fan of Tolkien as I am of Lewis, I really started reading Lewis' works; he had a talent for rooting out the spirituality of Christianity and getting to the essence of its beliefs without sanctimony.

I checked out some other current fantasy titles that used fallen angels, and while they addressed the fallen part of the situation, very few showed it from a Christian angle. I think God's Demon by Wayne Barlowe was the closest novel to presenting hell from a Christian viewpoint, and I love what Barlowe did with that story. The language he used, the characterization, and his perception of hell as an actual, physical place just knocked me for a loop.

Barlowe took the war in heaven and showed how the fallen angels fought. I've always been fascinated by the war in heaven and often wondered: what if it's still going on? I'm sacrilegious like that.

In the end, I fell in love with the absolute challenge of it. This is my own ego talking now, but I wanted to prove you could write a fantasy with Christians in it without the story becoming insipid or preachy. I began constructing Woerld and realized that all religions have some form of hell or purgatory, so realistically, it wouldn't be just Christians. I mean why would heaven only use a fraction of its forces to combat evil?

So the other religions started seeping in and with that there must be a hierarchy, and the structure of Woerld evolved until it became what it is in Miserere. The more I worked on it, the more detail seeped in, and again, I just loved the challenge of using real religions.

You have a male hero torn between and among a group of women: his sister, his former lover, and his new protégé. Was there a deliberate thought process behind the gender roles for these characters?

I wanted to step outside of a few of the standard fantasy tropes and twist them. The most common trope from the fairy tales of my youth was that of the beautiful princess who was captured by the evil warlord or witch and rescued by a handsome prince. I wanted to turn that trope upside down and show the handsome prince who was captured by the wicked queen and rescued by the beautiful princess. Only in Miserere, the prince takes a real beating from the wicked queen, the beautiful princess is mauled and half-mad, and the wicked queen isn't strung too tight either.

That was my primary thinking, then everything sort of got away from me. Most people are conditioned to see men in one of two roles: protector or aggressor. Lucian sees himself as the protector, even though it is Lindsay and Rachael who end up saving him more often than he saves them. He is determined not to abandon them, though, and that's important, that desire to be a part of someone's life even if it means constraints on his existence.

Nor did I want the women to be perfect. Rachael had her part in her own downfall; Catarina is a grand case of self-will run riot; and Lindsay thinks they're all being horribly unfair to Lucian while she downplays his crimes in her own mind.

When I got the cover art for Miserere (by the wonderful Michael C. Hayes), I just cried, it was better than anything I could have imagined. I had been dreading what an artist's conception of Miserere would be, but more than anything, I feared chain mail bikinis on the women and Lucian standing with Catarina and Rachael kneeling or the women pictured lower in the foreground.

Instead, Michael got exactly what I was doing and busted the tropes with me: they're all standing with their backs to one another; Rachael and Catarina are wearing the armor they would probably choose; Lucian is on his knees between them; and the walls of the Citadel rise behind them. Catarina's face is cunning, Rachael is distrustfully looking at Lucian, and Lucian—my

poor Lucian—looks to Heaven, because when you're trapped between those two women, your only salvation is from above.

Thanks to Teresa Frohock for answering my questions. Miserere: an Autumn Tale is available now from Night Shade Books.

Published on June 29, 2011 03:03

June 27, 2011

Review: Miserere by Teresa Frohock

It's not easy working religion into fantasy. Actually, that's the wrong word: I should say "faith." Anyone can invent a religion: both L. Ron Hubbard and George Lucas have made millions selling their made-up beliefs. But to depict the way faith works for people, the inner process of how belief gives strength, is hard. It always runs the risk of triteness if it's a fictional belief, or prosletyzing if it's not. And its very inclusion makes the reader question the author's motives.

Which is what makes Teresa Frohock's debut novel Miserere: an Autumn Tale that much more remarkable.

She creates a cosmology that includes our own world, as well as the alternate reality known as the Woerld. The fallen angels exiled from Heaven want to leave Hell and get their revenge on humanity, but to do so they have to get through the Woerld, a semi-medieval society where children plucked from our reality grow up to be the warriors of their new world. One of those warriors, Lucien, has betrayed both his order and his lover, abandoning her in (literal) Hell to aid his evil twin sister. He sets out to make amends, only to find himself saddled with a ten-year-old girl snatched from earth and fated to be a warrior-exorcist like him. Now he must battle to save her, convince his demon-possessed former love that he's changed, and prevent his twin from precipitating the final war between Heaven and Hell.

As anyone who's read my Eddie LaCrosse novels can tell, I'm a sucker for the warrior-battling-his-own-failures trope, and Lucien really delivers. He has done some truly ghastly things for all the wrong reasons, and ended up middle-aged, with a bad leg and a positively Wagnerian guilty conscience. Yet he's held on to a kernel of integrity, and he uses that to start his path to redemption. Rachael, his lover who is now possessed by a low-level demon that's taking her over bit by bit, is also seeking redemption for her own foolish trust and impulsiveness. And Lindsey, the girl fated to be a warrior-exorcist like Lucien, behaves and acts like a real ten-year-old, with all the strengths and weaknesses that entails.

These warriors call on their faith, reciting prayers to work magic. And their faith is unabashedly Christian, although it's made explicit that in Woerld all religions are represented equally and get along, the exact opposite of how they do here. And I suppose if God made swords glow and the earth open up to swallow enemies on request, faith would be a lot easier for the rest of us, too. But God isn't like the Force (which, with the advent of midichlorians, seems to be merely the static charge thrown off by viruses rubbing together): faith aids the warriors, but doesn't do the job for them.

And don't let all this talk of religion put you off, because Miserere is not a book with an agenda. First and foremost it's a fantasy adventure, with battles and chases and monsters. The extra depth and thoughtfulness Frohock brings to the story is gravy. I was asked to blurb this book, and after I read it, I did so with no reservations. I recommend it whole-heartedly to any fans of my books.

Watch for an interview with Teresa Frohock here in the near future.

Published on June 27, 2011 02:49

June 23, 2011

Just in: cover art for The Hum and the Shiver

Here's the final cover art for my next novel, out this September. The preliminary illustration used on Amazon featured a male figure, but since the book's protagonist is a young woman, Tor's awesome art deparment redid it.

What do you think?[image error]

Published on June 23, 2011 13:57

June 20, 2011

Advice to writers: swing for the fence

Sometimes I get asked for advice about being a writer.* Usually it's a general question such as, "How can I become a writer?" or "What should I write about?" The answer to the first is easy: you either are or you aren't, and deep down you know. But that second question is a tricky one. Conventional wisdom says "write what you know," but since I know nothing about being a sword jockey in a mythological world or a vampire in 1975 Memphis, I can't really get behind that answer. But I do have an answer. Sort of.

In the liner notes for his 1995 Greatest Hits compilation, Bruce Springsteen calls the song "Born to Run":

"My shot at the title. A 24 yr. old kid aimin' at 'the greatest rock 'n roll record ever.'"

In a 2003 interview, he elaborated:

"With that one I was shooting for the moon. I said, 'I don't want to make a good record, I want to make The Greatest Record Somebody's Ever Heard.' I was filled with arrogance and thought, I can do that, y'know?"

When I was a kid, the cliche was that anyone who wanted to be a writer presumably also wanted to write The Great American Novel. I never knew what that was exactly, but I assumed it was some sort of book that encapsulated the American experience in such a universal way that anyone who read it would immediately connect with it. There were contenders presented in English classes: The Grapes of Wrath and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn were the two most common. But neither connected with me. Either I was un-American, or the definition was essentially meaningless. Which it was, and is.

But it serves a purpose. Like "the greatest rock 'n roll record ever," it's a goal that we should have the arrogance to shoot for. Yet we don't. If anything, we're taught not to attempt it.

What passes for "serious" literature nowadays is often the result of multiple generations of writers going through MFA programs, publishing first novels of thinly-disguised coming-of-age autobiography, returning to academia as teachers and showing the next generation how to write and publish first novels of thinly-disguised coming-of-age autobiography. It's a recipe for institutionalized boredom that goes a long way toward explaining why you don't see so many bookstores anymore (and explains why something like David Foster Wallace'sThe Pale King, a novel literally about boredom, can gain such critical acclaim). The Great American Novel will never be produced by someone whose entire life consists of such limited experience.

Genre fiction, at least, is still popular (and believe me, I'm hugely grateful for that), but will never overcome the stigma attached to it (after all, it's "merely" science fiction, fantasy, mystery, etc.). And that's okay: we'll be happily serving our readers while the rest of the literary world wonders why no one reads anymore.

So where will the Great American Novel come from, then?

Beats me, but I do know one thing about it.

It will come from someone with the arrogance to shoot for the title.

So take your shot, man. Have the arrogance. Swing for the fence.

That's my advice.

*and that's especially funny since I've been writing all my life and my first novel didn't come out until I was over forty. But hey, people do ask.

In the liner notes for his 1995 Greatest Hits compilation, Bruce Springsteen calls the song "Born to Run":

"My shot at the title. A 24 yr. old kid aimin' at 'the greatest rock 'n roll record ever.'"

In a 2003 interview, he elaborated:

"With that one I was shooting for the moon. I said, 'I don't want to make a good record, I want to make The Greatest Record Somebody's Ever Heard.' I was filled with arrogance and thought, I can do that, y'know?"

When I was a kid, the cliche was that anyone who wanted to be a writer presumably also wanted to write The Great American Novel. I never knew what that was exactly, but I assumed it was some sort of book that encapsulated the American experience in such a universal way that anyone who read it would immediately connect with it. There were contenders presented in English classes: The Grapes of Wrath and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn were the two most common. But neither connected with me. Either I was un-American, or the definition was essentially meaningless. Which it was, and is.

But it serves a purpose. Like "the greatest rock 'n roll record ever," it's a goal that we should have the arrogance to shoot for. Yet we don't. If anything, we're taught not to attempt it.

What passes for "serious" literature nowadays is often the result of multiple generations of writers going through MFA programs, publishing first novels of thinly-disguised coming-of-age autobiography, returning to academia as teachers and showing the next generation how to write and publish first novels of thinly-disguised coming-of-age autobiography. It's a recipe for institutionalized boredom that goes a long way toward explaining why you don't see so many bookstores anymore (and explains why something like David Foster Wallace'sThe Pale King, a novel literally about boredom, can gain such critical acclaim). The Great American Novel will never be produced by someone whose entire life consists of such limited experience.

Genre fiction, at least, is still popular (and believe me, I'm hugely grateful for that), but will never overcome the stigma attached to it (after all, it's "merely" science fiction, fantasy, mystery, etc.). And that's okay: we'll be happily serving our readers while the rest of the literary world wonders why no one reads anymore.

So where will the Great American Novel come from, then?

Beats me, but I do know one thing about it.

It will come from someone with the arrogance to shoot for the title.

So take your shot, man. Have the arrogance. Swing for the fence.

That's my advice.

*and that's especially funny since I've been writing all my life and my first novel didn't come out until I was over forty. But hey, people do ask.

Published on June 20, 2011 03:21

June 14, 2011

Eddie LaCrosse IV has a title!

At last! I'm proud to announce the title of the fourth adventure of Eddie LaCrosse, out in 2012 from Tor Books:

WAKE OF THE BLOODY ANGEL.

What do you think?

WAKE OF THE BLOODY ANGEL.

What do you think?

Published on June 14, 2011 13:42