Alex Bledsoe's Blog, page 38

January 17, 2011

Thirty years of Excalibur

Thirty years ago the Arthurian myth first grabbed hold of me when I saw Excalibur on its initial release. Prior to that, I'd encountered King Arthur only through the Disneyfied Sword in the Stone, or the bloodless Technicolor epic Knights of the Round Table. John Boorman's 1981 film was different: limbs were hacked off, breasts were bared and there was a timeless sense of a blood-and-thunder past throbbing with life. Sure, it was stiff in places, and the acting was stylized to the point of ridiculousness, but it was still a movie in the pure sense, loaded with unforgettable images.

Thirty years on, I still love the film, and not just for sentimental reasons. There's a sure hand at work, one that knows exactly what it wants to accomplish with every shot and sequence. Boorman, who'd once tried to wrangle Lord of the Rings onto the screen as a live-action epic, is a fearless filmmaker as notable for his daring successes (Deliverance) as his audacious failures (Exorcist II: The Heretic). He depicts Arthur not as a neat or elderly monarch, but with the long hair and scruffy beard of a biker. Guinevere is an earthy princess who knows herbal remedies as well as courtly dances. Lancelot, in gleaming silver armor, has the curls and square jaw of a laid-back surfer. Boorman uses green backlight to give even the metal armor a hint of the organic, most beautifully during the emergence of the sword from the lake. The actors don't perform so much as embody their roles, as the film tends to show them only at moments of high emotion.

But the wild card is Nicol Williamson as Merlin. Whatever the behind-the-scenes process that arrived at this interpretation, Williamson is both the focal point and the most entertaining thing in the film. Using every possible range of his voice, clad in a silver skullcap and black ragged robes, he's a buffoon one moment, a sage the next, and never less than enthralling. Whenever the film seems about to take itself too seriously, Williamson saves the day with a pratfall or a goofy line reading.

I can understand why contemporary viewers might find it overblown and silly. In an age of ironic detachment, when everything has a wink-wink element, the worst offense is to take something seriously, and to unapologetically present a unique vision.

Excalibur does exactly that. And if you let it cast its spell (which goes something like, "Anál nathrach, orth' bháis's bethad, do chél dénmha") I think you'll find yourself watching it again in another thirty years, too.

Published on January 17, 2011 03:01

January 15, 2011

Who, at the Beginning

I have a soft spot for the current incarnation of the British show Doctor Who that can be distilled down to a comment made by the title character during the recent Christmas special. When told by a villainous type than someone "wasn't important," the Doctor replied, "I've never met anyone who wasn't important." That sort of unabashed optimism and compassion, especially when so much TV SF tends toward the downbeat and dystopian, really appeals to me.

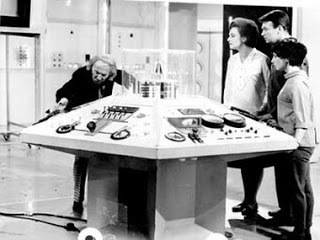

So I decided to check out the original episodes of the original show, made and broadcast in 1963 (the same year I was made and broadcast). The first episode, the Ur-Who if you will, is called "An Unearthly Child." And in it, you will see nothing of the show that's so popular now.

Well, that's not true. There's the T.A.R.D.I.S., still in the form of a police call box. But there's no sonic screwdriver. The Doctor is revealed to be an alien, but he's a crotchety old man with an equally alien teenage granddaughter in tow. Susan, for reasons not really revealed in the first eleven episodes (where I stopped), is enamored of Earth in the twentieth century and tries to blend in at the local school. Two of her teachers, Ian and Barbara, decide to find out why she gave the school a phony address, and end up antagonizing the Doctor (not hard to do) into proving the T.A.R.D.I.S. is real. First they travel into the past and run afoul of cavemen, then to the future where for the first time they meet the Doctor's greatest enemies, the Daleks.

The dynamics are so vastly different that it's hard to believe the current Doctor (Matt Smith) is actually supposed to be part of the same continuity. Made as a children's show, the audience identification figure is Susan, while authority is represented by Ian and Barbara, two gigantically annoying companions. The Doctor is the anarchic wild card, omnipotent one moment and completely at a loss the next. Further, the humanistic determination to help those in need that characterizes the recent Doctor(s) is completely missing. This original Doctor is quite willing to run away, abandon Ian and Barbara (can't argue with that, really) and look out for himself and Susan at the expense of anyone else. And yet he's not the total dickweed this makes him sound like; he abhors violence, is resourceful in a pinch and, as played by William Hartnell, is generally a hoot to watch. There's none of David Tennant's wide-eyed lunacy, or Matt Smith's quirky body language, but he conveys how fast the Doctor's brain works and how tedious normal people must be to him.

Ten Doctors later, there's virtually nothing from this original conception left in the show beyond the T.A.R.D.I.S. The new show has a budget, terrific special effects and casts that can bring this goofy universe to thrilling life. Yet there's something delightful in the original concept of a bad-tempered, super-intelligent alien dragging his granddaughter's snooty teachers through space and time for no good reason. While it seems unlikely that the current run of young, handsome Doctors will end anytime soon, I have a sneaking wish for a return to Hartnell's conception. It's in the same wish box that has Michael Keaton in a film version of The Dark Knight Returns and Alec Guinness playing Obi-Wan Kenobi in Lucas' original concept as Ben Grimm from Treasure Island. None of them will ever happen. But thinking about them sure is fun.

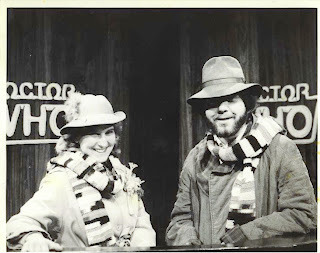

This is me and Suzie Hunt on the campus PBS station circa 1983, hosting a fundraiser during the broadcast of The Five Doctors. I was chosen for this because I was one of the few people at UT-Martin who'd ever heard of Who.

So I decided to check out the original episodes of the original show, made and broadcast in 1963 (the same year I was made and broadcast). The first episode, the Ur-Who if you will, is called "An Unearthly Child." And in it, you will see nothing of the show that's so popular now.

Well, that's not true. There's the T.A.R.D.I.S., still in the form of a police call box. But there's no sonic screwdriver. The Doctor is revealed to be an alien, but he's a crotchety old man with an equally alien teenage granddaughter in tow. Susan, for reasons not really revealed in the first eleven episodes (where I stopped), is enamored of Earth in the twentieth century and tries to blend in at the local school. Two of her teachers, Ian and Barbara, decide to find out why she gave the school a phony address, and end up antagonizing the Doctor (not hard to do) into proving the T.A.R.D.I.S. is real. First they travel into the past and run afoul of cavemen, then to the future where for the first time they meet the Doctor's greatest enemies, the Daleks.

The dynamics are so vastly different that it's hard to believe the current Doctor (Matt Smith) is actually supposed to be part of the same continuity. Made as a children's show, the audience identification figure is Susan, while authority is represented by Ian and Barbara, two gigantically annoying companions. The Doctor is the anarchic wild card, omnipotent one moment and completely at a loss the next. Further, the humanistic determination to help those in need that characterizes the recent Doctor(s) is completely missing. This original Doctor is quite willing to run away, abandon Ian and Barbara (can't argue with that, really) and look out for himself and Susan at the expense of anyone else. And yet he's not the total dickweed this makes him sound like; he abhors violence, is resourceful in a pinch and, as played by William Hartnell, is generally a hoot to watch. There's none of David Tennant's wide-eyed lunacy, or Matt Smith's quirky body language, but he conveys how fast the Doctor's brain works and how tedious normal people must be to him.

Ten Doctors later, there's virtually nothing from this original conception left in the show beyond the T.A.R.D.I.S. The new show has a budget, terrific special effects and casts that can bring this goofy universe to thrilling life. Yet there's something delightful in the original concept of a bad-tempered, super-intelligent alien dragging his granddaughter's snooty teachers through space and time for no good reason. While it seems unlikely that the current run of young, handsome Doctors will end anytime soon, I have a sneaking wish for a return to Hartnell's conception. It's in the same wish box that has Michael Keaton in a film version of The Dark Knight Returns and Alec Guinness playing Obi-Wan Kenobi in Lucas' original concept as Ben Grimm from Treasure Island. None of them will ever happen. But thinking about them sure is fun.

This is me and Suzie Hunt on the campus PBS station circa 1983, hosting a fundraiser during the broadcast of The Five Doctors. I was chosen for this because I was one of the few people at UT-Martin who'd ever heard of Who.

Published on January 15, 2011 03:01

January 7, 2011

The Finn Substitution

Some have brewed a ha-ha about a new edition of Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that removes what is euphemistically called "the N word" and replaces it with the word, "slave." This has brought all kinds of interesting trivia to light ("the N word" is used 219 times in Finn, "slave" is not actually a synonym for it, Finn is the fourth most-banned book in the country, etc.). But as I read the ever-increasing attempts to be the most offended by this, I can only think: what's the big deal? It was done twenty years ago, too, and no one thought anything about it. In fact, it's been done multiple times.

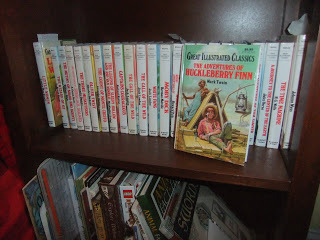

The one with which I'm most familiar is part of the Great Illustrated Classics series that takes well-known (and public domain) novels and repackages them for young readers, simplifying the stories and adding illustrations on every facing page. We have a shelf of them, and I've enjoyed reading them aloud to my kids (my oldest son's favorite is Journey to the Center of the Earth). And we've read both Finn and Tom Sawyer. Finn was published in 1990, and to my knowledge has never stirred the least bit of ire.

Now I admit, in reading Sawyer, it annoyed me that villainous Injun Joe was now "Crazy Joe." I understood the impulse to change it, but I disagreed with it. Similarly, in their version of Finn there's no "N word," and the dialogue has been rewritten so that no one-for-one substitution is needed. Jim is a slave, and that's enough.

So why all the outrage about this new edition that boldly goes where...well, many have gone before?

Probably for two reasons. First, the recent release of The Autobiography of Mark Twain, a volume he stipulated could only be published a century after his death. It's both a best seller and a critical darling, so Twain is back in the public eye.

And two...well, now there's the internet, and people on the internet love to be offended. Any time there's an issue like this, people rush to show how outraged they are, in a pile-on usually as distasteful as whatever the original offense might've been.* You can see some of it here and here. Even Roger Ebert, who should really know better, chimed in with a particularly crass and tasteless tweet.

Yes, rewriting Finn bugs me, but I'll respond in the proper adult fashion: by not buying this edition. That's all any of us need to do, to register our disapproval. I won't rant and rave about the greater social ills its existence reveals, or try to show how much more it offends me than it does anyone else.

I'm not defending this editorial bowdlerizing by any means; I disapprove of it, and think the concepts behind it are both shallow and wrong. But it's not real censorship as long as the original text is available. And I'm pretty sure it still is.

*(And yes, I recognize the potential hypocrisy in saying this in the context of a post that could be interpreted as doing exactly that. If you think so, please disregard anything I say.)

The one with which I'm most familiar is part of the Great Illustrated Classics series that takes well-known (and public domain) novels and repackages them for young readers, simplifying the stories and adding illustrations on every facing page. We have a shelf of them, and I've enjoyed reading them aloud to my kids (my oldest son's favorite is Journey to the Center of the Earth). And we've read both Finn and Tom Sawyer. Finn was published in 1990, and to my knowledge has never stirred the least bit of ire.

Now I admit, in reading Sawyer, it annoyed me that villainous Injun Joe was now "Crazy Joe." I understood the impulse to change it, but I disagreed with it. Similarly, in their version of Finn there's no "N word," and the dialogue has been rewritten so that no one-for-one substitution is needed. Jim is a slave, and that's enough.

So why all the outrage about this new edition that boldly goes where...well, many have gone before?

Probably for two reasons. First, the recent release of The Autobiography of Mark Twain, a volume he stipulated could only be published a century after his death. It's both a best seller and a critical darling, so Twain is back in the public eye.

And two...well, now there's the internet, and people on the internet love to be offended. Any time there's an issue like this, people rush to show how outraged they are, in a pile-on usually as distasteful as whatever the original offense might've been.* You can see some of it here and here. Even Roger Ebert, who should really know better, chimed in with a particularly crass and tasteless tweet.

Yes, rewriting Finn bugs me, but I'll respond in the proper adult fashion: by not buying this edition. That's all any of us need to do, to register our disapproval. I won't rant and rave about the greater social ills its existence reveals, or try to show how much more it offends me than it does anyone else.

I'm not defending this editorial bowdlerizing by any means; I disapprove of it, and think the concepts behind it are both shallow and wrong. But it's not real censorship as long as the original text is available. And I'm pretty sure it still is.

*(And yes, I recognize the potential hypocrisy in saying this in the context of a post that could be interpreted as doing exactly that. If you think so, please disregard anything I say.)

Published on January 07, 2011 03:25

December 26, 2010

Saved by Darkness

In 1978, I was as hardcore a geek/nerd/dweeb as a boy could be. Star Wars had come upon the world, legitimizing those of us who read books with spaceships and monsters on the covers (and got beaten up by our cousins for it, but that's another blog post). Starlog magazine was hot. TV had The Six Million Dollar Man, The Bionic Woman and the original Battlestar Galactica. Even music was jumping on the star wagon: Styx had spaceships at the climax of "Come Sail Away" and a Tolkein tribute song on their album Pieces of Eight. Heck, the entire British progressive rock scene owed as much to fantasy literature as it did to rock and roll. The time was right for me to undergo the final metamorphosis into the kind of genre fan and writer who lives, breathes and dreams about spaceships and dragons, lost in a world of imagination and whimsy.

But I was saved at the last minute from this darkness, by Darkness.

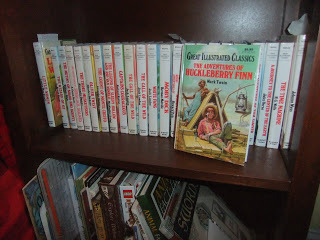

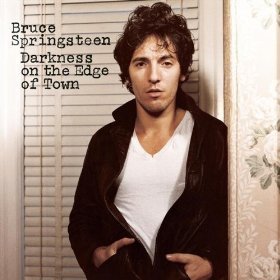

Bruce Springsteen's fourth album appeared in 1978. Prior to this, I knew him primarily from FM radio, which had introduced him via "Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)." But now I was right there for the new album, and because of it, nothing would be the same.

The music on Darkness is solid and muscular, made up of snarling guitars and surging keyboards. But the lyrics are what make it special, and what made me connect with it. The romantic escape of his prior work is gone, burned out and swept away. Every song is about people trapped in small-town lives, in soul-crushing ennui where dreams no longer matter. Yet in each song is a kernel of something that might be hope.

What really spoke to me were the songs about fathers and sons. By its very title, "Adam Raised a Cain" states its purpose, and musically recreates all those arguments between every dad and every son. "Factory," which at first seems so slight it might be filler, actually described my own father's life in painful detail. In fact, for the first time I realized it was possible to make music--and by extension, any kind of art--from someone's own life. Not in the literal autobiographical sense, but through feelings that everyone understood and experienced, emotions other than the "love/escape/party" music on the radio. Or the "heroic destiny/good vs evil/love conquers all" tropes at the heart of what I read, listened to and watched.

Because of this music, I stayed connected to the world in a way I otherwise might not have, and often against my will. No matter how much I wanted to disappear into the Federation, the Rebellion, Pern or Shannara, the Boss would drag me back. Because I became a long-term Springsteen fan, I couldn't ignore or escape the real world. And when I began to synthesize the things I loved (horror and fantasy) with this real-world connection, I found my voice as a writer.

This is all fresh in my mind due to the release of The Promise, an exhaustive 3 CD/3 DVD set chronicling the making of the album. But I'd steer anyone interested simply to the album itself. Everything I talk about is there. And if you're a fan of my books, then you'll be able to share the moment when I turned onto the path that eventually led to the stories you enjoy.

But I was saved at the last minute from this darkness, by Darkness.

Bruce Springsteen's fourth album appeared in 1978. Prior to this, I knew him primarily from FM radio, which had introduced him via "Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)." But now I was right there for the new album, and because of it, nothing would be the same.

The music on Darkness is solid and muscular, made up of snarling guitars and surging keyboards. But the lyrics are what make it special, and what made me connect with it. The romantic escape of his prior work is gone, burned out and swept away. Every song is about people trapped in small-town lives, in soul-crushing ennui where dreams no longer matter. Yet in each song is a kernel of something that might be hope.

What really spoke to me were the songs about fathers and sons. By its very title, "Adam Raised a Cain" states its purpose, and musically recreates all those arguments between every dad and every son. "Factory," which at first seems so slight it might be filler, actually described my own father's life in painful detail. In fact, for the first time I realized it was possible to make music--and by extension, any kind of art--from someone's own life. Not in the literal autobiographical sense, but through feelings that everyone understood and experienced, emotions other than the "love/escape/party" music on the radio. Or the "heroic destiny/good vs evil/love conquers all" tropes at the heart of what I read, listened to and watched.

Because of this music, I stayed connected to the world in a way I otherwise might not have, and often against my will. No matter how much I wanted to disappear into the Federation, the Rebellion, Pern or Shannara, the Boss would drag me back. Because I became a long-term Springsteen fan, I couldn't ignore or escape the real world. And when I began to synthesize the things I loved (horror and fantasy) with this real-world connection, I found my voice as a writer.

This is all fresh in my mind due to the release of The Promise, an exhaustive 3 CD/3 DVD set chronicling the making of the album. But I'd steer anyone interested simply to the album itself. Everything I talk about is there. And if you're a fan of my books, then you'll be able to share the moment when I turned onto the path that eventually led to the stories you enjoy.

Published on December 26, 2010 08:48

December 3, 2010

Meet the Queen of the Lot

This is the final post on films I watched over the Thanksgiving holiday. I watched other films (Leatherheads, Pandorum, Coffee and Cigarettes), but there isn't much to say about them. I'm ending on a high note, though.

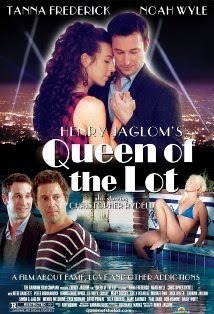

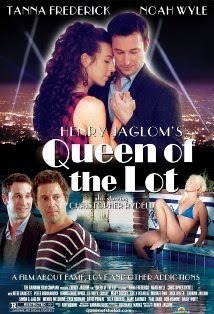

A while back I stumbled across the work of Henry Jaglom, a filmmaker who's been forging his own indie path for forty years. He existed on the periphery of my cinema consciousness until I saw Last Summer in the Hamptons on cable and suddenly realized here was this totally original artist, untouched by any popular trends, with a consistent (and consistently fascinating) body of work.

His latest film is Queen of the Lot, a follow-up to 2006's Hollywood Dreams. Both star Tanna Frederick, an actress notable for her total emotional clarity; she communicates everything her characters feel with her whole being. There's a moment in her previous collaboration with Jaglom, Irene in Time, that is probably one of the most amazing bits of non-acting acting I've ever seen. For her to have such a response, she would have to genuinely feel the moment to a degree most film actresses wouldn't dare, and couldn't pull off.

In Queen, Tanna is back as Margie, an actress on the make who hides a will of steel behind a "gosh-shucks" Iowa farmgirl exterior. Yet the Iowa farmgirl isn't exactly a put-on, either. She's the star of a successful action franchise, and is dating a hot established star, but wants more (she compulsively checks her Google points). She's also under house arrest after two DUIs in one week.

Jaglom's films are as much about locations as they are characters, and the film divides itself between two main spaces: the opulent home of Margie's managers (Zack Norman and David Proval), and the family homestead of her boyfriend Dov (Christopher Rydell), scion of a fading clan of Hollywood royalty. In the first setting Margie knows her role; in the latter she's afloat, especially when she meets her boyfriend's normal, sane brother Aaron (Noah Wyle). She gets into everyone's good graces by taking them at face value, something these crass, jaded, sophisticated people almost can't comprehend. But is she showing her true face to them?

That probably makes the film sound more serious than it feels, because ultimately it's a pretty amusing story. Jaglom's improvisational methods allow the actors to essentially make up the dialogue as they go, and since many of them are playing performers as well, they know the territory. Frederick and Wyle have great chemistry together, and though she's the star, he becomes the story's center; he sees through Margie, but at the same time responds to the parts that feel genuine, just as we do. A real surprise is Jaglom's daughter Sabrina, who gives real bite to her performance as a resourcefully conniving teen.

But the show belongs to Frederick. Jaglom tends to make his films around specific actresses; he had an extraordinary run with his wife Victoria Foyt, and his collaborations with Frederick have brought him into new territory. He's found a context for her unique energy and given her strong co-stars to bounce off, something many filmmakers (and actresses) would avoid. As for Frederick, she brings a level of emotional intensity and honesty to Margie that feels at times like a documentary. I've never seen another performer consistently seem so absolutely unaware of the camera's presence and risk the kind of things she does.

I'd love to see Jaglom and Frederick revisit Margie every few years, in between other projects like Irene in Time. If the funny, touching Queen of the Lot is any indication, the character and milieu are far from exhausted, and Ms. Frederick remains a wonder to watch.

A while back I stumbled across the work of Henry Jaglom, a filmmaker who's been forging his own indie path for forty years. He existed on the periphery of my cinema consciousness until I saw Last Summer in the Hamptons on cable and suddenly realized here was this totally original artist, untouched by any popular trends, with a consistent (and consistently fascinating) body of work.

His latest film is Queen of the Lot, a follow-up to 2006's Hollywood Dreams. Both star Tanna Frederick, an actress notable for her total emotional clarity; she communicates everything her characters feel with her whole being. There's a moment in her previous collaboration with Jaglom, Irene in Time, that is probably one of the most amazing bits of non-acting acting I've ever seen. For her to have such a response, she would have to genuinely feel the moment to a degree most film actresses wouldn't dare, and couldn't pull off.

In Queen, Tanna is back as Margie, an actress on the make who hides a will of steel behind a "gosh-shucks" Iowa farmgirl exterior. Yet the Iowa farmgirl isn't exactly a put-on, either. She's the star of a successful action franchise, and is dating a hot established star, but wants more (she compulsively checks her Google points). She's also under house arrest after two DUIs in one week.

Jaglom's films are as much about locations as they are characters, and the film divides itself between two main spaces: the opulent home of Margie's managers (Zack Norman and David Proval), and the family homestead of her boyfriend Dov (Christopher Rydell), scion of a fading clan of Hollywood royalty. In the first setting Margie knows her role; in the latter she's afloat, especially when she meets her boyfriend's normal, sane brother Aaron (Noah Wyle). She gets into everyone's good graces by taking them at face value, something these crass, jaded, sophisticated people almost can't comprehend. But is she showing her true face to them?

That probably makes the film sound more serious than it feels, because ultimately it's a pretty amusing story. Jaglom's improvisational methods allow the actors to essentially make up the dialogue as they go, and since many of them are playing performers as well, they know the territory. Frederick and Wyle have great chemistry together, and though she's the star, he becomes the story's center; he sees through Margie, but at the same time responds to the parts that feel genuine, just as we do. A real surprise is Jaglom's daughter Sabrina, who gives real bite to her performance as a resourcefully conniving teen.

But the show belongs to Frederick. Jaglom tends to make his films around specific actresses; he had an extraordinary run with his wife Victoria Foyt, and his collaborations with Frederick have brought him into new territory. He's found a context for her unique energy and given her strong co-stars to bounce off, something many filmmakers (and actresses) would avoid. As for Frederick, she brings a level of emotional intensity and honesty to Margie that feels at times like a documentary. I've never seen another performer consistently seem so absolutely unaware of the camera's presence and risk the kind of things she does.

I'd love to see Jaglom and Frederick revisit Margie every few years, in between other projects like Irene in Time. If the funny, touching Queen of the Lot is any indication, the character and milieu are far from exhausted, and Ms. Frederick remains a wonder to watch.

Published on December 03, 2010 03:07

December 1, 2010

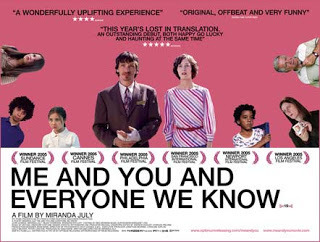

Do I want to know Me and You and Everyone We Know?

Madison, WI poet Lisa Marie Brodsky recommended Miranda July's 2005 film Me and You and Everyone We Know, and I finally watched it over the holiday weekend. It's an indie film in the broadest sense, made by an outsider artist and about outsider people, some of whom do things so confoundingly odd that you wonder if they exist anywhere but in a film like this.

It's a film about relationships, about people reaching for meaningful connection in all the wrong ways. The central character, Christina (Ms. July), is a conceptual artist who sends positive messages out into the universe in the (so far) vain hope that they might bring love and happiness into her own life. She meets Richard (John Hawkes), a divorced father of two who barely functions and perpetually looks quite literally stunned. Richard's two children have inherited this inability to make appropriate decisions about closeness, leading them to odd connections with some of the other characters. It's one of those films where everyone turns out to be far less than six degrees away from everyone else, whether they know it or not.

July herself, as Christine, is a touching screen presence, so delicately lost and lonely that her art-inspired attempts to reach out seem incredibly brave. As a writer, she has penned not just this script but a collection of short stories, and knows how to structure multiple narrative lines so they flow and resonate. And as a director, she gets amazingly unaffected performances from the younger actors.

The issue I had with the film was how I felt about some of these connections. It's clear what the movie wants me to think, as every shot and music cue is used to cast a wistful, hopeful glow over things that perhaps shouldn't be considered as such. Some of the connections--for example, between a first-grader and an unknowing adult woman via online sex chat--are just inherently uncomfortable, and no amount of sensitive scoring or empathetic performance can overcome that. So I tried to decide: do I give in and feel what the film wants me to feel, or do I stay true to my own deep-seated and possibly Philistine responses despite my wish to like the film's view of the world?

Speaking of these same issues, Rogert Ebert in his review says, "I know this sounds perverse and explicit, and yet the fact is, these scenes play with an innocence and tact that is beyond all explaining." In Variety, Scott Foundas says these things "...sound puerile or even irresponsible, then it is all the more to July's credit that she embellishes such moments with a whimsy and melancholia that makes them seem less about sex than about making meaningful connections with other human beings." So should I admire this, the way Jessica Winter does in the Village Voice ("...July ascribes sexuality to persons under the age of consent without coyness or moral hectoring") or should I go with my emotional reaction, driven by my feelings as both a parent and a writer ("The movie engendered the kind of uncomfortable, crawling-out-of-your-skin feeling I get when I'm subjected to bad performance art," as said by Sam Adams in Philadelphia's City Paper).

Even after a few days pondering it, I'm still not sure. I know what Ms. July wants me to feel; I just don't know if I'm ready, willing or able to feel it. I asked Ms. Brodsky, who'd originally recommended the film, for her thoughts and she summed it up pretty well: "Miranda July is a brilliant voice in contemporary literature and film. She seems to do everything. She'll also make you squirm in your seat with the uncomfortable truth, so beware."

Published on December 01, 2010 02:13

November 29, 2010

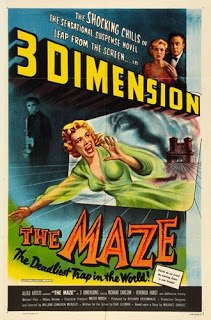

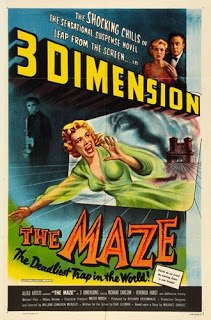

What lies (er, hops) at the heart of The Maze?

One of the best thing about holidays? Catching up on movies! Over the next few days I'll be writing about some of the more interesting flicks I saw over the long weekend, starting with 1953's The Maze.

I remember watching The Maze at my uncle's house in Columbia, TN when I was a kid. I was too young for post-modern irony, so I took it at face value, and two things stayed with me: the nature of the monster at the end, and the "rational" explanation given for it.

Recently a friend found me a copy (it's never been "officially" released), and I was pleasantly surprised. The Maze is a low-budget little gem, full of surprisingly good things that balance out the...well, the undeniably goofy premise.

Kitty (Veronica Hurst) is engaged to Gerald (Richard Carlson), who is suddenly called back to his ancestral Scottish estate. Soon he breaks his engagement, but Kitty doesn't go down without a fight. With her spunky Aunt Edith in tow, she crashes Castle Craven and demands answers, especially when Gerald seems to have aged 20 years in a few weeks. When she doesn't get them, she sets out to find them on her own. What she turns up is...unexpected. WARNING: spoilers to follow.

Carlson, a veteran of It Came from Outer Space and Creature from the Black Lagoon, is adequately emo as the tortured Gerald, but Hurst is a surprisingly tough-minded and resourceful heroine. She never falters in her determination to help Gerald, even when he insists he doesn't need it. She isn't one of those easily frightened scream queens, so when she does finally shriek, it's for a good reason. She's a welcome relief from the distressed damsels of so many similar films.

The film was originally made in 3D, and the depth of composition is interesting even in a flat image. The weird framing device (Aunt Edith narrating as essentially a disembodied head at the bottom of the frame) might have made more sense in 3D. And the use of the titular maze is creepily effective, on a low-budget par with what Kubrick did in The Shining.

But nothing compares to the nature of the monster, or the villain, or whatever one would call Sir Roger, the Baronet McTeam. He is, in fact, a 200 year old, sentient, man-sized bullfrog.

Yep.

The film handles this in the only way possible, by keeping Sir Roger out of sight for most of the story, and almost gets away with quick glimpses during the climax. It's only the long shots, where the whole unfortunate costume is seen, and his rather silly demise that break out the giggles.

And much like the postscript of Psycho, we get a scientific explanation for what we've just seen. Seems that there was once an accepted theory called "phylogeny," which said that the human embryo goes through all the stages of evolution from invertebrate to mammal. Sir Roger, unfortunately, didn't develop past amphibian.

Sure, it's goofy. It was probably goofy in 1953. But it's also delightfully creepy, if you can put aside your post-modern irony.

Thanks to Bobbie at Junkyard Films for sending me this jewel.

I remember watching The Maze at my uncle's house in Columbia, TN when I was a kid. I was too young for post-modern irony, so I took it at face value, and two things stayed with me: the nature of the monster at the end, and the "rational" explanation given for it.

Recently a friend found me a copy (it's never been "officially" released), and I was pleasantly surprised. The Maze is a low-budget little gem, full of surprisingly good things that balance out the...well, the undeniably goofy premise.

Kitty (Veronica Hurst) is engaged to Gerald (Richard Carlson), who is suddenly called back to his ancestral Scottish estate. Soon he breaks his engagement, but Kitty doesn't go down without a fight. With her spunky Aunt Edith in tow, she crashes Castle Craven and demands answers, especially when Gerald seems to have aged 20 years in a few weeks. When she doesn't get them, she sets out to find them on her own. What she turns up is...unexpected. WARNING: spoilers to follow.

Carlson, a veteran of It Came from Outer Space and Creature from the Black Lagoon, is adequately emo as the tortured Gerald, but Hurst is a surprisingly tough-minded and resourceful heroine. She never falters in her determination to help Gerald, even when he insists he doesn't need it. She isn't one of those easily frightened scream queens, so when she does finally shriek, it's for a good reason. She's a welcome relief from the distressed damsels of so many similar films.

The film was originally made in 3D, and the depth of composition is interesting even in a flat image. The weird framing device (Aunt Edith narrating as essentially a disembodied head at the bottom of the frame) might have made more sense in 3D. And the use of the titular maze is creepily effective, on a low-budget par with what Kubrick did in The Shining.

But nothing compares to the nature of the monster, or the villain, or whatever one would call Sir Roger, the Baronet McTeam. He is, in fact, a 200 year old, sentient, man-sized bullfrog.

Yep.

The film handles this in the only way possible, by keeping Sir Roger out of sight for most of the story, and almost gets away with quick glimpses during the climax. It's only the long shots, where the whole unfortunate costume is seen, and his rather silly demise that break out the giggles.

And much like the postscript of Psycho, we get a scientific explanation for what we've just seen. Seems that there was once an accepted theory called "phylogeny," which said that the human embryo goes through all the stages of evolution from invertebrate to mammal. Sir Roger, unfortunately, didn't develop past amphibian.

Sure, it's goofy. It was probably goofy in 1953. But it's also delightfully creepy, if you can put aside your post-modern irony.

Thanks to Bobbie at Junkyard Films for sending me this jewel.

Published on November 29, 2010 03:00

November 9, 2010

Pictures from World Fantasy Convention 2010

A few pictures from World Fantasy. I was too busy to take very many, unfortunately.

Me and my tablemate Travis Heerman, author of Heart of the Ronin, at the mass signing Saturday night.

Me and Amelia Beamer, author of The Loving Dead (which I reviewed here). Amelia also interviewed me for Locus magazine.

Me with Tom Doherty, head of Tor Books.

From left. Anthony Huso, author of The Last Page; author Brandon Sanderson's assistant (his name escapes me); Tobias Buckell, author of Halo: The Cole Protocol; Tobias's twin daughters; Tobias's wife Emily; Tor editor Paul Stevens; Marie Brennan, author of A Star Shall Fall; and me.

A treasure found in the hotel parking garage.

Me and my tablemate Travis Heerman, author of Heart of the Ronin, at the mass signing Saturday night.

Me and Amelia Beamer, author of The Loving Dead (which I reviewed here). Amelia also interviewed me for Locus magazine.

Me with Tom Doherty, head of Tor Books.

From left. Anthony Huso, author of The Last Page; author Brandon Sanderson's assistant (his name escapes me); Tobias Buckell, author of Halo: The Cole Protocol; Tobias's twin daughters; Tobias's wife Emily; Tor editor Paul Stevens; Marie Brennan, author of A Star Shall Fall; and me.

A treasure found in the hotel parking garage.

Published on November 09, 2010 02:58

November 5, 2010

The Loving Dead: zombies with one thing on their minds

When it comes to the living dead, I'm strictly vanilla. I want my zombies slow, shambling, mindless and prolific. I have no time for zombies that run, or speak, or suffer from a virus and aren't really zombies. So I began reading Amelia Beamer's The Loving Dead with a bit of trepidation, since her zombies are not only virus-spawned (and thus not technically dead), the virus is an STD. These zombies are both hungry, and horny.

But there's more at work here. For while the book breaks a lot of my zombie preference rules, it does include one thing I believe is essential for every good horror story: a level of metaphor. The Loving Dead may be about individual characters, but it's also about a specific class of people: disaffected urban twentysomethings so unused to having anything truly matter that, when the first zombies appear, their initial reaction is to pop in a DVD of Night of the Living Dead. Not to get survival hints, mind you, but just because of the association.

Michael and Kate are platonic housemates and co-workers at a San Francisco Trader Joe's. They throw a costume party the night the zombie apocalypse begins, and initially think it's all part of the game. When they realize it's not, but can find no corroborative evidence on TV or the internet, they're completely at a loss. Separated for most of the story, the twin narratives draw them together at the safest place they can imagine: the island of Alcatraz.

The book reminded me most of a fairly obscure Japanese SF film called Matango, or in America, Attack of the Mushroom People. In it, a shipwreck maroons a bunch of 60s-era affluent Japanese on a strange island, where they contribute absolutely nothing to their own survival before they apathetically mutate into the titular mushroom people. In its native country it was seen as a mocking attack on middle-class complacency; recut for the States, it came across as a big helping of WTF? But The Loving Dead shares its sense of a generation so unaccustomed to anything geniune that, when real danger arrives, they can only ignore it, or relate to it through pop culture. By the end, it's an open question whether the zombies or the humans are the most adrift in their world.

The Loving Dead is published by Night Shade Books.

Published on November 05, 2010 02:26

October 31, 2010

Helsinki Homicide: ice cold crime without "girl" in the title

Scandanavian thrillers are all the rage right now thanks to Steig Larsson, but I've been a fan of this sub-genre since Peter Hoeg's novel Smilla's Sense of Snow and the original Norwegian version of the film Insomnia. Larsson's Millenium trilogy may be the Hunger Games of its moment, but recently I discovered another Scandanavian author, from Finland, whose crime novels are much more to my taste.

Jarrko Sipila is a novelist and crime reporter whose "Helsinki Homicide" series has just begun being translated into English. The first one, Against the Wall, won the 2009 award for Best Finnish Crime Novel. It details the investigation into the murder of a young hoodlum mixed up in customs fraud, and follows parallel paths as both the criminal underworld and the police force seek the motive behind the crime.

It does something I love, best exemplified by the Michael Mann film Manhunter: it makes you hope that real cops are as smart, resourceful and tenacious as the ones in the story. The team under Lieutenant Kari Takamaki is unified by their dedication to duty, a Hawksian professionalism that needs no trite character justifications. These men and women do their job because it's their job, and they get their satisfaction from doing it to the best of their abilities. This is what separates them from the criminals, who are equally smart and resourceful but prey to disloyalty, greed and complex bonds of loyalty and revenge. The cops win by essentially maneuvering the bad guys into tripping over their own worst tendencies.

It's a bit hard to evaluate Sipila's style, since it's translated to English from Finnish; apparently the only word the two languages share is "sauna." He started as a journalist, so I imagine in his native Finnish his prose is punchy, succinct and vivid; if it's a little clunky in English, I can live with that. I had no issue with one common criticism, the complex Finnish names, except where two very similar ones (Lindstrom and Lydman) were concerned. Still, the cleverness of the plotting, the broad strokes of character and the unique milieu come through just fine. And what connects with the reader is the universality of it all: criminals have the same motives in Helsinki that they do anywhere else, and cops want to catch them for the same reasons they do in New York or LA.

Against the Wall is followed by Vengeance, which is near the top of my to-be-read pile. Hopefully more of the series will make it into English as well, because tough, honest crime novels are always welcome.

Sipila's novels in English are available directly from the Minneapolis publisher, Ice Cold Crime.

Published on October 31, 2010 22:31