C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 45

October 16, 2015

Smoke and Mirrors

This week I had my first repeat interview with an author for New Books in Historical Fiction. Besides marking a milestone for the podcast channel itself, the interview gave me some interesting insight into the broader themes that can animate an individual writer’s work.

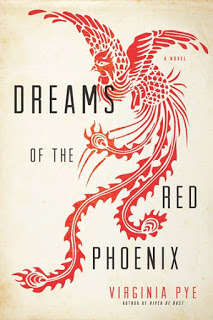

This week I had my first repeat interview with an author for New Books in Historical Fiction. Besides marking a milestone for the podcast channel itself, the interview gave me some interesting insight into the broader themes that can animate an individual writer’s work.Virginia Pye’s first book, River of Dust , which we discussed in September 2013, focused on the tragedy of parents who lose their only child to abduction. But that novel—like her Dreams of the Red Phoenix , released just this week—also explores the complex mix of awareness and misunderstanding that affects people living far from home, in a culture they believe they know but in which they remain forever strangers, separated from those around them by assumptions so deeply held that neither side questions them. Some of these assumptions come perilously close to prejudices, but Pye’s characters are, for the most part, well-meaning people, their errors the result more of natural arrogance or a failure of imagination than of malicious intent.

Like River of Dust, Dreams of the Red Phoenix is set in northwestern China among a community of missionaries from the United States. The Reverend Caleb Carson is in fact the nephew of John Wesley Watson, the minister in the first book. (The two stories are, however, completely independent—not part of a series.) Twenty-seven years have passed, and expectations have changed. Yet the smoke and mirrors remain, obscuring both sides of the cultural exchange even as war and revolution threaten to complete the destruction wrought by the perennial dangers of drought and hunger.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Of the brutal conflicts that characterized the twentieth century, none equaled in scale the catastrophe that struck China when the Japanese occupied the northern part of the country just as the Civil War was picking up steam. According to some estimates, 22.5 million people died in these twin acts of destruction. Dreams of the Red Phoenix (Unbridled Books, 2015) takes place during a few weeks in the summer of 1937, as seen from the perspective of North American missionaries who only think they understand the local culture and their place in it.

Sheila Carson—mourning the recent death of her husband, the Reverend Caleb—can hardly bring herself to get up in the morning, let alone supervise work around her house or rein in her teenaged son, Charles, who soon causes trouble for himself and his mother by taunting the Japanese soldiers who patrol the area. But when attacks on the civilian population send a stream of wounded and hungry people into the mission looking for aid, Shirley, one of the few trained nurses in the compound, is pulled into service, her house turned into a clinic. The mission’s protected status, based on U.S. neutrality in these years before World War II, falls under threat when the Japanese army suspects that the refugees include Nationalist and Communist soldiers, and Shirley must decide whether to leave with her fellow Americans or stay and help the charismatic Communist general whose philosophy appeals to her idealistic nature. Her memories of her husband, her responsibilities as a mother, and her own sense of right and purpose are pushing Shirley in different directions even before outside forces intervene to complicate her path.

As in her earlier novel, River of Dust, Virginia Pye here takes stories of her own ancestors—in this case, her grandmother and family friends—and weaves them into a vivid, evocative tapestry of love and loss, belonging and alienation, deception and truth.

Published on October 16, 2015 06:00

October 9, 2015

Everyday Heroines

A couple of weeks ago, I mentioned the Five Directions Press library panel on “Everyday Heroines.” Those of you who have read my novels, especially The Golden Lynx and The Winged Horse, are entitled to a quiet snicker here.

Sure, Sasha, the female protagonist in Desert Flower and Kingdom of the Shades, could be considered an ordinary person—if ordinary people routinely start training in exquisite but intense art forms at the age of four and rise to the pinnacle of their profession by the early twenties. Nina, heroine of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, is a graduate student in history—at an elite university, yes, but still a quite ordinary person in her own right. In the book, however, she is running around aristocratic London playing Lady Marguerite Blakeney, at least until she lands in the French countryside, where she has to adopt one persona after another, most of them members of the hoi polloi.

The Legends of the Five Directions series, though, mostly takes place at the highest levels of Muscovite and Tatar society. Of the recurring characters, only Grusha, the Kolychevs’ slave, can really be considered an everyday heroine. Everyone else—even the wicked Semyon—belongs to the lineage of khans, beys, or the tight circle of boyar families who wielded real power at the Russian court. Grand Prince Vasily III expanded that circle in an attempt to secure the place of his young son, the future Ivan the Terrible, but the number of qualifying lineages remained small. The Tatar preference for polygamy multiplied the number of direct descendants of Genghis Khan with each generation, but the insistence on charismatic authority that prevailed for so long on the steppe and in the khanates set those descendants apart from the mass. So Nasan, Ogodai, Tulpar, and their kin are also not everyday heroes.

Except in one sense. Like most of the premodern world, Muscovite and Tatar society imposed strict limitations on the choices available to all individuals—male and female, rich and poor. Women, especially, were confined to the domestic sphere, their influence on outside affairs restricted to pillow talk and its daytime equivalent or wielded indirectly through the birthing and education of children. Noblewomen called the shots within their households, managing others who did the work, but the tasks themselves differed little between noble estate and peasant cottage.

For men, too, birth determined one’s profession. Peasants farmed, artisans learned their fathers’ trade, merchants inherited their business, priests raised priests’ sons to succeed them, and noblemen went to war—every year, on command, to defend the state or attack its neighbors as required. When Fedor Kolychev ran off to become a monk, he did it in secret. His choice was unusual; noblemen usually stayed within the political and military role to which they were born.

And of course, by the standards of the day, no one—aristocrat or peasant—had a free say in whom he or she married. If anything, nobles had less say than peasants, who had a chance of recognizing their future spouses by sight. Aristocratic marriages determined political alliances, and marriage of a daughter to the grand prince (later tsar) was the $64,000 prize. Grooms sometimes had a say, brides hardly ever; parents on both sides made the match, and the young couple adapted as well as possible after the wedding. Such alliances have been common throughout the world, of course, not only in Muscovite Russia.

Social standing certainly affects one’s quality of life, and in general, it is more comfortable to be rich and respected than poor and downtrodden. But throughout history, membership in society has imposed constraints on both the high and the low. In that sense, even elite heroines face everyday problems.

Image: Konstantin Makovsky, The Kissing Custom, via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on October 09, 2015 11:43

October 2, 2015

A New Kind of Indie Bookstore

Last Friday, JJ Marsh of Triskele Books posted an interview with the author and illustrator Patti Brassard Jefferson. The interview is not about Jefferson’s books but about her bookstores—specifically, her idea to open P.J. Boox, a physical/online bookstore specializing in the works of self-published and small-press-published authors. The store was due to open yesterday, and you can find more information about it at its website.

Last Friday, JJ Marsh of Triskele Books posted an interview with the author and illustrator Patti Brassard Jefferson. The interview is not about Jefferson’s books but about her bookstores—specifically, her idea to open P.J. Boox, a physical/online bookstore specializing in the works of self-published and small-press-published authors. The store was due to open yesterday, and you can find more information about it at its website.To me, this sounds like a really interesting idea. It hasn’t been tried before, so far as I know, and a few kinks need working out before I sign on. The proposed arrangement is not yet the partnership of which I dream. Essentially, it differs little from the consignment system that bookstores currently use for non-trade-published books—when they accept those books at all. Authors and publishers pay to rent space in the store, pay for the online setup, provide the physical copies of books to sell (including shipping costs). In return, they receive 95% of sale prices via Paypal. But they have to take the sales figures on faith, and if they live far from the store, they depend on the store owner to promote the books. A committed, knowledgeable owner may do just that, but it seems pretty obvious that the owners have a guaranteed income stream from authors and publishers, who pay up front, and a much smaller income from sales. Authors and publishers, in effect, are gambling that exposure will raise their sales enough to cover the start-up costs and make a profit. A fairer arrangement, to my way of thinking, is for stores to buy the books from authors at a steep discount (say, production cost plus the author’s regular royalty), which would allow the stores to sell the books at a price that competes with the rates online. Then both sides get something from the transaction, and everyone benefits from sales rather than shelf rentals.

Even so, the idea of a bookstore focusing on the “little guys” is both clever and promising. It recognizes that good self- and independently published books exist and that promotion in bookstores is as, if not more, important for their authors than for those picked up by commercial publishers. It adds a layer of curation: covers and text have to look professional, reassuring prospective readers that books meet basic standards. It responds to readers’ preference for books they can see: all books face out, displaying those beautiful covers to attract the eye. And it acknowledges the important role traditionally played by independent booksellers, who know their stock and their clientele and can talk up works to individual customers, just as librarians do.

So a big cheer for the innovators, best wishes to Ms. Jefferson for success with her bookstore for indies, and hopes that her venture will prompt others to follow suit. As the e-book and associated print revolutions continue, the number of Hidden Gems continues to rise. Having more ways to discover such books can only benefit readers, writers, small presses, and the bookstore owners willing to bring in non-trade-published books for sale.

Variety is the spice of life, as they say. So let’s hear it for the adventurous cooks!

Image from Clipart.com, no. 22079092.

Published on October 02, 2015 06:00

September 25, 2015

The King's Sisters

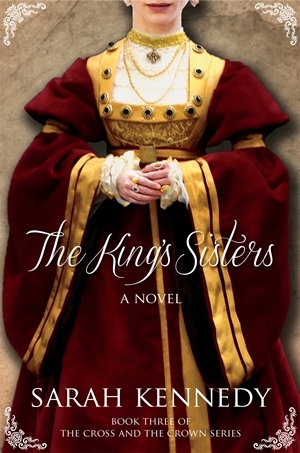

A while back, I did a series of posts on women’s lives in the past—the expectations of and restrictions on women, as well as certain unexpected opportunities available to them to exercise power and authority. One of those posts looked at women religious and included a picture of Julian of Norwich, the fourteenth-century anchorite who influenced the great of her world, despite not leaving her cell for decades. My current interview on New Books in Historical Fiction explores the moment when, for the women of England, that option disappeared.

A while back, I did a series of posts on women’s lives in the past—the expectations of and restrictions on women, as well as certain unexpected opportunities available to them to exercise power and authority. One of those posts looked at women religious and included a picture of Julian of Norwich, the fourteenth-century anchorite who influenced the great of her world, despite not leaving her cell for decades. My current interview on New Books in Historical Fiction explores the moment when, for the women of England, that option disappeared.When I agreed to speak with Sarah Kennedy, the author of The Cross and the Crown series, I was drawn mostly by the idea of a Tudor-era novel that did not feature Henry VIII’s romantic intrigues. That the first novel begins a year later than The Golden Lynx, but in a quite different setting, was an additional draw. Only as I read the books—and even more during my discussion with their author—did I realize how much Henry’s Dissolution of the Monasteries undercut one of the few opportunities available to women to live in independent (or at least semi-independent) communities where they could obtain an education, practice medicine, and exercise authority both within their convents and, to some extent, within the Church. The dispossessed nuns could not marry without a special dispensation from the king; at the same time, they had no means of support except meager and seldom-paid pensions. In a stroke of the pen, they became dependents and, if their families did not or could not reclaim them, often paupers.

As Kennedy points out, Henry’s attack on the Church formed part of a greater drive to centralize power in the hands of the king. In this drive, the nuns were collateral damage. Yet for women who had devoted their lives to the Church only to find themselves without a home, the destruction of the convents inflicted real harm. And a door once open to England’s unmarriageable daughters closed forever.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Many historical novels explore the highways and byways of Tudor England, especially the marital troubles of Henry VIII, which makes it all the more pleasant when an author approaches that much-visited time and place with a fresh eye. In her The Cross and the Crown series—which currently consists of The Altarpiece, City of Ladies, and The King’s Sisters—Sarah Kennedy looks at Henry’s roller-coaster search for marital happiness and male progeny from the viewpoint of a young nun cast out of her convent and flung into a strange interim state where she can neither practice her religion nor marry without the express permission of the king.

We meet Catherine Havens in 1535. King Henry has recently declared the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and the local gentry sees a chance to increase its landholdings at the expense of Catherine’s convent—a development that her abbess in no way supports but cannot prevent. When the convent chapel’s large and valuable altarpiece goes missing, the questions raised by the theft and the attempts to retrieve it sweep Catherine into a secular world that her sheltered background has not prepared her to handle. The situation only deepens in future books, as the king’s constantly shifting moods, loves, alliances, and attitudes toward religion keep his realm in equally constant turmoil—the only certainty that a misstep will lead to torture and execution.

In this atmosphere, no one is safe. Yet Catherine and the other “king’s sisters,” a group that includes his divorced wife Anne of Cleves, strive to care for his children while remaining true to their consciences. That Catherine is also a gifted physician (although a woman cannot bear that title, and the line between medicine and witchcraft at times wears disturbingly thin) offers her both a means of support and a certain protection amid the many dangers that beset even secondary affiliates of the royal court. The King’s Sisters (Knox Robinson Publishing, 2015) opens a window on a world in which the fate of Anne Boleyn is but one reminder of King Henry’s caprice.

Published on September 25, 2015 06:00

September 18, 2015

Books Worth Reading

This week’s post focuses on updates about Five Directions Press and its authors.

This week’s post focuses on updates about Five Directions Press and its authors.On Wednesday, September 16, three of us—Ariadne, Courtney, and myself—gave a panel at one of the local libraries. A lively group of people showed up, which was quite charming of them, since through a certain lack of foresight we turned out to compete with the second Republican debate—if anyone can compete with the Donald. We talked about everyday heroines in our novels and answered a bunch of questions about our books, writing, and publishing with a small press. We also had a lot of fun, and the library supplied great snacks. We had such a good time we plan to repeat the experience at other local libraries, so check our News and Events page every so often to find out more. This was also our first chance to display our brand new banner, shown above.

At this time last week, we also released the first issue of Books Worth Reading, our quarterly newsletter. Congratulations to Satya Nelms, who chose the e-book version of my Kingdom of the Shades as her prize. Satya is also an author, although not one of ours, so check out her site and her books. She has written a hidden gem of her own, a novella called Hello, Morning!

At this time last week, we also released the first issue of Books Worth Reading, our quarterly newsletter. Congratulations to Satya Nelms, who chose the e-book version of my Kingdom of the Shades as her prize. Satya is also an author, although not one of ours, so check out her site and her books. She has written a hidden gem of her own, a novella called Hello, Morning! This issue of the newsletter also features an interview with Five Directions Press author Ariadne Apostolou, author of the contemporary novel Seeking Sophia and the soon-to-be-released set of four related novellas, West End Quartet. Find out more about her, her books, and the inspiration for her writing on our new newsletter archive page. (Note that the archive page lists only the main story or stories from a given issue; subscribe to see all the news and be entered in future raffles.) As Words with JAM editor JJ Marsh put it back in October 2013, “This is a writer who can do big picture and microscopic detail, depending on how it serves the story. I thoroughly enjoyed Kleio's journey, the vivid characters, the riotous description of scenery and the perfectly structured narrative through which the reader feels both wiser and more naive.”

Future issues of the newsletter will focus on other authors and books worth reading, not only by members of Five Directions Press. If you have a suggestion for books or writers (novelists, primarily) you’d like to know more about, e-mail us or contact us via our website, Facebook, or Twitter with your ideas. And don’t forget to like/follow us there and at Instagram.

There’s plenty of time yet to sign up for the December newsletter. You can find Subscribe buttons at the main entry page at the Five Directions Press site and on our Contact page. You can also just send us an e-mail. The reason you’d want to sign up is because we are planning a Christmas giveaway: a swag bag including one or more of our novels, bookmarks, and other goods to be determined. Anyone on our subscription list by Thanksgiving will be entered into the raffle.

Check back next week for information on my New Books in Historical Fiction interview with Sarah Kennedy, whose The King’s Sisters (The Cross and the Crown 3) is fresh off the press this week.

Published on September 18, 2015 06:00

September 11, 2015

One Step Forward

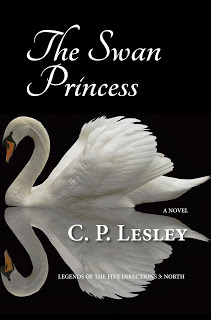

On Labor Day, at 3:30 or so in the afternoon, I typed the last sentence of the rough draft of The Swan Princess. This is always a bittersweet moment, when a book that began life as a vague idea, almost an image, congeals into a visible shape. Not yet an adult shape, fully formed, but a real story with a beginning, a somewhat hairy middle, and an end. I have left the stage of pure imagination and moved into the (for me) even more vital stage of revision.

On Labor Day, at 3:30 or so in the afternoon, I typed the last sentence of the rough draft of The Swan Princess. This is always a bittersweet moment, when a book that began life as a vague idea, almost an image, congeals into a visible shape. Not yet an adult shape, fully formed, but a real story with a beginning, a somewhat hairy middle, and an end. I have left the stage of pure imagination and moved into the (for me) even more vital stage of revision.The bittersweet quality was particularly pronounced with this book. Like many writers, I find beginnings and endings easier than middles, which have to sustain interest and develop the plot and characters without rushing to the resolution of problems. Perhaps because The Swan Princess is also the fulcrum of the series—the third of the five directions—finding its heart became a slog in a way that the first two books never were and I hope the last two will not be (since I already know their basic stories). The whole novel is, in a sense, a middle—focused on development and the retention of interest more than resolution.

Of course, I still have a long way to go. As tends to happen with my stories, characters insisted on doing things for reasons I don’t yet understand and that may not work when I do figure it out. On the whole, the resolutions at the end mirror the problems established at the beginning, but a few hares I started in chapter 1 veered off into the woods in chapter 8 and never returned. I have either to catch them and bring them back or erase any traces of their presence. Key secondary characters vanish for long stretches of time and need invitations to check in once a while before the reader forgets them and their concerns. At least one minor character requires building up, whereas others will do better with some trimming. The spiritual and political background so important to the series as a whole so far appears in patches, at best.

But the book was also a learning experience for me. I discovered that, however hard I cling to the illusion, I cannot outline a novel. I need to see it on the page in all its glorious complexity and illogic. I find the characters, the plot, the dialogue, and the settings by writing them out. Even comments from other trusted writers can’t help much at the start, because until I know what course the story will take, I have no way to assess whether I should push a problematic incident in this direction or that, give it more space or cut it altogether. Once that spine exists—sketched out and filled with place-holding clichés as it inevitably is (because if I stop to edit, I will not move the story forward)—then constructive criticism works, because I can figure out how to respond.

A few days to revel in the sensation of accomplishment, and it’s back to the drawing board—or in this case, writing desk—to prune the dead wood and nurture the sprouts that see the sun only in chapter 10. With luck, the revisions will go faster than stage 1, and I’ll have completed my sixth novel late this year or early in the next. And when I start book 7, I’ll know to lock myself in the office and write it down, warts and all, before inflicting it on my long-suffering, endlessly patient and helpful critique group. But then, I already have a good idea of what should happen in The Vermilion Bird....

Speaking of my critique group, if you happen to live in the Philadelphia area, three of us are giving a panel at the Helen Kate Furness Free Library next Wednesday, September 16. Stop by and say hello. You can find full information and sign up on Facebook or get time and place from the Five Directions Press site. Hope to see you there!

Published on September 11, 2015 06:00

September 4, 2015

The Totenberg Violin

There was a wonderful story on National Public Radio about a month ago. The New York Times picked it up the next day. In brief, on the day the story broke, the FBI planned to restore a Stradivarius violin to the NPR correspondent Nina Totenberg and her sisters. Roman Totenberg, Nina’s father and a renowned concert violinist who lived to the age of 101, had played this violin for almost forty years until it disappeared one day from his office. He had long suspected the thief’s identity, but he never had enough evidence for the police to get a warrant. Then, a few months ago, the widow of the suspected thief discovered the violin in the attic and took it for appraisal to an expert, and that expert recognized it as the Ames Stradivarius stolen from Roman Totenberg thirty-five years ago.

There was a wonderful story on National Public Radio about a month ago. The New York Times picked it up the next day. In brief, on the day the story broke, the FBI planned to restore a Stradivarius violin to the NPR correspondent Nina Totenberg and her sisters. Roman Totenberg, Nina’s father and a renowned concert violinist who lived to the age of 101, had played this violin for almost forty years until it disappeared one day from his office. He had long suspected the thief’s identity, but he never had enough evidence for the police to get a warrant. Then, a few months ago, the widow of the suspected thief discovered the violin in the attic and took it for appraisal to an expert, and that expert recognized it as the Ames Stradivarius stolen from Roman Totenberg thirty-five years ago.The ins and outs of this story—and I’ve given only the rough outlines here—would draw any novelist. My first thought was for the widow. What would it be like to discover, years after your husband died, that he had stolen a musical instrument worth, even at the time, upward of $250,000, then kept that secret from you? How would that change the story you had told yourself your entire adult life—about your husband, your marriage, and yourself? (Note that we are talking about fiction here, so whether the actual widow knew or suspected the truth or was as innocent as she claimed is entirely irrelevant to the power of any resulting novel.)

I give this example because one of the questions writers are most often asked is where we get our ideas, as if the world were a marvelously logical place in which nothing fiction-worthy ever happens. On the contrary, on any given day, the issue is not finding ideas—one good look at the newspaper will suggest half a dozen—but disciplining oneself not to dash after each new and shiny possibility, leaving the current story unfinished.

Ideas are everywhere. Let a character voice into your head and start asking questions about who she is or what he wants, and ideas will start pouring into your head. The trick is to filter them out, to focus on the ones that serve this particular story, fit this individual character. I have a whole Storyist file called “Ideas,” where I jot down the ones that appeal to me most (yes, the Totenberg violin is there!). But I know I will never have time to explore half of them. I have three Legends novels to go, then at least one book to follow the left-over characters—and, oh yes, more Tarkei Chronicles begging for their time in the sun. I just hope I live long enough to complete them, although I will definitely work some of those lurking ideas into the plots.

And that is why writing fiction is so much fun.

Stradivarius violin image from Pixabay. No attribution required.

Published on September 04, 2015 06:00

August 28, 2015

Farewell, Summer

For me, today—more accurately, Sunday—marks the last day of summer. Sure, Labor Day doesn’t arrive until September 7, and the fall equinox a full two weeks after that. But Sunday ushers in the end of my summer writing vacation, and the month that follows promises more projects to complete than time to complete them. Unless I can clear the decks for another week in late October/early November, I will be back to weekend-only writing until the winter holidays roll around.

Naturally, worse fates exist than having too much work. And weekend writing can be fun, too. But this last vacation week of the summer has a special charm, not least because I have finally closed in on the ending of The Swan Princess, a destination I have spent much of the last year fearing that I would never reach. I wouldn’t call the monstrosity that clogs up my Storyist file a first draft, more like beta version 0.5. The thing has the grace of an untended rosebush, with thorny branches entangling in every direction, long twigs of abandoned plot points sticking out, flowers in every stage of growth and disintegration, and nasty blank spots indicating points of view that appear far too late in the tale for a well-constructed novel. The minute I type “THE END,” I have to return to the beginning and haul out the pruning shears.

But literary pruning adapts itself well to weekend writing, and with five other novels under my belt, I feel confident that I can impose the structure needed to straighten out this tangled mess. And that will really be something worth celebrating.

But for the moment, please excuse the short post as I rush back to the Russian North. With the end of summer so close, I don’t want to waste a minute of these last writing days!

The image of the pier comes from Pixabay, a site for free, professional-quality photographs, vectors, and illustrations run out of Germany. If you have ten acceptable photographs to upload, you can avoid the ads, but the standards are high: the site rejected six of my best offerings. But even if your skills with the camera are as pathetic as mine, the site is worth a look.

Published on August 28, 2015 06:00

August 21, 2015

Bitter Harvest

When I began my Legends of the Five Directions series, I knew the time would come when I would have to deal with what historians call the Starodub War. It was a small war, as wars go, just one stage in the long conflict between the adjacent powers of Russia and Poland-Lithuania, with a little help (or hindrance, depending on one’s point of view) from various Tatar hordes. It lasted from 1534 to 1537, although it would have been over in half the time if the diplomats had spent more time negotiating and less posturing.

When I began my Legends of the Five Directions series, I knew the time would come when I would have to deal with what historians call the Starodub War. It was a small war, as wars go, just one stage in the long conflict between the adjacent powers of Russia and Poland-Lithuania, with a little help (or hindrance, depending on one’s point of view) from various Tatar hordes. It lasted from 1534 to 1537, although it would have been over in half the time if the diplomats had spent more time negotiating and less posturing. There was no way to avoid it: like all noblemen in the sixteenth century, my hero Daniil and his relatives, as well as the khans and sultans of Kasimov, served in the Russian army from the age of fifteen until death or total debility, whichever came first. Boyars did other things, too: served at court, acted as regional governors, went on diplomatic missions, and the like. But since the series begins in February 1534 and will certainly not end before 1538, it seemed unlikely that every male character would somehow miraculously avoid time at the front. Daniil doesn’t even want to escape his responsibilities; he enjoys the challenges of military life, although his view of war naturally becomes more nuanced as he ages. The Swan Princess is the book that tackles, at least peripherally, the effects of the Starodub War on the lives of those who serve—and those who stay at home.

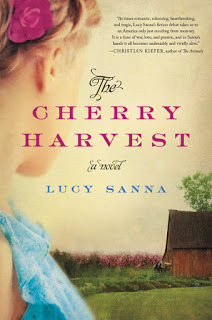

Alas, I am not Bernard Cornwell—much as I admire his Saxon Tales. Writing fight scenes just does not appeal to me. I am more interested in relationships, whether between husbands and wives, parents and children, siblings, or mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law. Even so, I recognize the power of war as a disruptor of human life, a driver of conflict both raw and emotional. And so I was immediately drawn to Lucy Sanna’s The Cherry Harvest, which manages in rich and beautiful prose to explore the complex and varied reactions caused by World War II without ever leaving Wisconsin. Even the title is simultaneously evocative and deceiving: what can a cherry harvest have to do with Adolf Hitler?

But I’m not telling. You will have to read the book to find out. Or listen to the interview, then read the book.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Many novels look at World War II—what happened, why it happened, how the world would have changed if the war had never occurred or had taken a different course. Lucy Sanna, in The Cherry Harvest (William Morrow, 2015), approaches World War II from a different perspective: its impact on farming communities in the Midwest and the little-known history of German prisoners of war brought for confinement to the United States.

By May 1944, Charlotte Christiansen has reached the end of her rope. The cherry harvest of 1943 has rotted on the tree because the migrant laborers who once worked on her farm have found better-paying jobs in factories. Charlotte has been reduced to butchering her daughter’s prized rabbits in secret and trading eggs and milk for meat if she is to feed her family. But the local country store has canceled her line of credit, and if she and her husband cannot find enough workers to pick the 1944 harvest, they will lose everything they have. So when Charlotte learns that the US government will send German prisoners of war into rural communities to bring in the crops, she urges the local county board to, in the words of one member, make “a bargain with the devil.”

The prisoners defy the farmers’ worst expectations. Some of them deny any adherence to the Nazi cause; some are barely out of their teens; one, obviously educated and cultured, speaks English well enough to develop a friendship with Charlotte’s family. The community’s resistance to their presence gradually ebbs. Then Charlotte’s son returns from fighting the Nazis, only to find them harvesting cherries in his own back yard.

In this beautifully written and poignant story, Lucy Sanna explores the complexity of love and loyalty in a world where even the distant echoes of war prove impossible to ignore.

Published on August 21, 2015 06:00

August 14, 2015

Author or Characters?

A few weeks ago, I interviewed Glen Craney for New Books in Historical Fiction. I wrote about that interview and his book, as I usually do, on the week when the interview went live. Even at the time, I meant to revisit the discussion to pick up on a point he made that I found particularly interesting (there were many such points, actually—it was a great interview, and he had lots of fascinating things to say). Specifically, he mentioned that readers sometimes conflate his point of view with his characters’.

In The Spider and the Stone, Craney tells the story of Scotland’s First War of Independence from the perspective of the Scots, most notably but not exclusively Sir James Douglass, the friend and staunch supporter of Robert the Bruce, the eventual if temporary winner of that war. From the viewpoint of the Scots, the English and their king, Edward I Longshanks, are heartless invaders, opportunistically profiting from the inability of the Scots clans to settle on a leader. In brief, the English don’t come off well in this story, and readers—perhaps understandably—see the author, too, as arguing for the Scots side.

To some extent, this problem affects all historical novelists. Values differ across time and space, and a good novel must reflect that. This truth is giving me fits in The Swan Princess, where my Tatar warriors are rampaging about the forest seeking vengeance. However pacifist my inclinations may be, I would be writing farce, not historical fiction, if I let my warriors throw an arm around the villain’s shoulders and invite him to talk it out over dinner. Instead, they burn villages, shoot first and ask questions later, and generally act like medieval troops. At other times, they recite poetry and appreciate good architecture—they are characters, not clichés—but when push comes to shove, they do not flinch.

Still, Craney’s point seems to me broader than simple reverence for the historical past. Certainly, his characters too behave in ways that were appropriate for the times but seem abominably harsh today. But is it true that authors are also drawn to the sides that appeal to them in a given historical context: the Scots over the English, the Tatars over the Russians (or vice versa)?

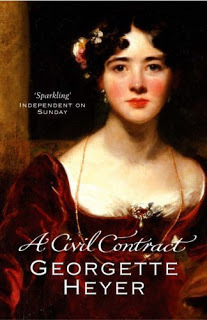

I had already been thinking about this question in a different context. One of the GoodReads groups I especially like has been running a Heyer Read (that’s Georgette Heyer, the Queen of Regencies, if you somehow made it out of high school without immersion in the lives of Justin, Dominic, Léonie, Deborah, Max, Arabella, Frederica, Venetia, and their ilk). In July we read one of her later novels, A Civil Contract, about a marriage of convenience between a near-bankrupt viscount and the rich merchant’s daughter he marries, because the noble bride he wants is as impoverished as he and he doesn’t like to put her father to the trouble of refusing his suit. Adam, the viscount, is unfailingly polite to his bourgeois Jenny, even recognizing in due course that life has led him in the right direction after all. But Jenny—who loves him, although she never admits it—goes to ridiculous lengths in her efforts to make him comfortable, never considering her own needs so long as she fulfills what she considers the duties of a wife. Sweet as she is, and as poignant and complex as Heyer portrays their relationship to be, Jenny’s self-abnegation ultimately leaves this reader thinking that Betty Friedan should have come along a good 150 years earlier than she did.

Such an attitude toward marriage and wifely duties, of course, was not unusual in 1815, when the book was set, or even in the 1950s, when Heyer wrote A Civil Contract. I had just about decided, like Glen Craney’s readers, that she had been drawn to the topic because it expressed her own views when August arrived, with The Masqueraders in tow.

I have read The Masqueraders many times. It is my favorite Heyer novel (Faro’s Daughter is a close tie, and A Civil Contract, despite my occasional desire to give Jenny a good shake, is no. 3). I wouldn’t dream of spoiling it for you by giving away the plot, so I will just quote this passage from near the end.

And indeed, she is not. Ignore the absurd use of “child” to address a twenty-six-year-old woman; pretty much everyone in this novel addresses others as “child,” whether they are older or younger. Prudence, at this moment, is wearing men’s clothes. In the last few hours, she has knocked one officer of the law out of a coach, held another at sword point, and escaped over the fields with Anthony. She can fight a duel, run a gambling house, hold her liquor in a hard-drinking age, and rescue a hapless maiden. She does do her best to convince the man she loves that he would do better to marry elsewhere, but only because she believes that he would come to dislike her ramshackle life. She is as different from Jenny as the proverbial chalk from cheese. Yet the same author created them both.

Part of the joy of writing fiction is the opportunity it offers to submerge oneself in the emotions and thoughts of others—something we cannot do in real life, however much we care for someone, however well we think we know them. That’s as true for authors as for readers. Each character is distinct; each character has his or her own take on the world. But that take is not necessarily the author’s, however strongly the illusion is, for a while, sustained.

In The Spider and the Stone, Craney tells the story of Scotland’s First War of Independence from the perspective of the Scots, most notably but not exclusively Sir James Douglass, the friend and staunch supporter of Robert the Bruce, the eventual if temporary winner of that war. From the viewpoint of the Scots, the English and their king, Edward I Longshanks, are heartless invaders, opportunistically profiting from the inability of the Scots clans to settle on a leader. In brief, the English don’t come off well in this story, and readers—perhaps understandably—see the author, too, as arguing for the Scots side.

To some extent, this problem affects all historical novelists. Values differ across time and space, and a good novel must reflect that. This truth is giving me fits in The Swan Princess, where my Tatar warriors are rampaging about the forest seeking vengeance. However pacifist my inclinations may be, I would be writing farce, not historical fiction, if I let my warriors throw an arm around the villain’s shoulders and invite him to talk it out over dinner. Instead, they burn villages, shoot first and ask questions later, and generally act like medieval troops. At other times, they recite poetry and appreciate good architecture—they are characters, not clichés—but when push comes to shove, they do not flinch.

Still, Craney’s point seems to me broader than simple reverence for the historical past. Certainly, his characters too behave in ways that were appropriate for the times but seem abominably harsh today. But is it true that authors are also drawn to the sides that appeal to them in a given historical context: the Scots over the English, the Tatars over the Russians (or vice versa)?

I had already been thinking about this question in a different context. One of the GoodReads groups I especially like has been running a Heyer Read (that’s Georgette Heyer, the Queen of Regencies, if you somehow made it out of high school without immersion in the lives of Justin, Dominic, Léonie, Deborah, Max, Arabella, Frederica, Venetia, and their ilk). In July we read one of her later novels, A Civil Contract, about a marriage of convenience between a near-bankrupt viscount and the rich merchant’s daughter he marries, because the noble bride he wants is as impoverished as he and he doesn’t like to put her father to the trouble of refusing his suit. Adam, the viscount, is unfailingly polite to his bourgeois Jenny, even recognizing in due course that life has led him in the right direction after all. But Jenny—who loves him, although she never admits it—goes to ridiculous lengths in her efforts to make him comfortable, never considering her own needs so long as she fulfills what she considers the duties of a wife. Sweet as she is, and as poignant and complex as Heyer portrays their relationship to be, Jenny’s self-abnegation ultimately leaves this reader thinking that Betty Friedan should have come along a good 150 years earlier than she did.

Such an attitude toward marriage and wifely duties, of course, was not unusual in 1815, when the book was set, or even in the 1950s, when Heyer wrote A Civil Contract. I had just about decided, like Glen Craney’s readers, that she had been drawn to the topic because it expressed her own views when August arrived, with The Masqueraders in tow.

I have read The Masqueraders many times. It is my favorite Heyer novel (Faro’s Daughter is a close tie, and A Civil Contract, despite my occasional desire to give Jenny a good shake, is no. 3). I wouldn’t dream of spoiling it for you by giving away the plot, so I will just quote this passage from near the end.

Sir Anthony propped the [barn] door wide to let in the moonlight. “Empty,” he said. “Can you brave a possible rat?”

Prudence was unbuckling her saddle-girths. “I’ve done so before now, but I confess I dislike ’em.” She lifted off the saddle and had it taken quickly from her.

“Learn, child, that I am here to wait on you.”

She shook her head, and went on to unbridle the mare. “Attend to Rufus, my lord. What, am I one of your frail, helpless creatures then?”

And indeed, she is not. Ignore the absurd use of “child” to address a twenty-six-year-old woman; pretty much everyone in this novel addresses others as “child,” whether they are older or younger. Prudence, at this moment, is wearing men’s clothes. In the last few hours, she has knocked one officer of the law out of a coach, held another at sword point, and escaped over the fields with Anthony. She can fight a duel, run a gambling house, hold her liquor in a hard-drinking age, and rescue a hapless maiden. She does do her best to convince the man she loves that he would do better to marry elsewhere, but only because she believes that he would come to dislike her ramshackle life. She is as different from Jenny as the proverbial chalk from cheese. Yet the same author created them both.

Part of the joy of writing fiction is the opportunity it offers to submerge oneself in the emotions and thoughts of others—something we cannot do in real life, however much we care for someone, however well we think we know them. That’s as true for authors as for readers. Each character is distinct; each character has his or her own take on the world. But that take is not necessarily the author’s, however strongly the illusion is, for a while, sustained.

Published on August 14, 2015 06:00