C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 42

May 13, 2016

Less Alone, More Together

Five Directions Press is growing. Eight years after we became a writing group and four years after founding our coop, we have added two new members and will soon have four new books listed on our site (five new books in print, one of which has been featured on the site for a while).

Five Directions Press is growing. Eight years after we became a writing group and four years after founding our coop, we have added two new members and will soon have four new books listed on our site (five new books in print, one of which has been featured on the site for a while).Denise Allan Steele writes contemporary fiction set in her Scottish homeland and her adopted country, the United States. She is in the midst of revising her novel Rewind, which takes a humorous look at the ins and outs of love and politics under Margaret Thatcher—and how decisions made then reverberate decades later. We hope to have it available by the end of this year.

Gabrielle Mathieu, our first overseas member, joins us from Switzerland. Her Falcon trilogy straddles the line between historical fantasy and historical fiction. In 1950s Switzerland, Peppa, an unconventional young woman trying to make ends meet for a few weeks until she reaches the age of twenty and can inherit the legacy left by her father, unwittingly tumbles into a research program run by a sinister and cynical scientist. What is her connection with the falcon? Where does reality blend into drug-induced hallucinations? You will have to read this tightly plotted, deeply experienced story to find out—and even then you may wonder. Book 1, The Falcon Flies Alone, is planned for release in late summer or fall.

Another fall release will be the first book in Courtney J. Hall’s five-part Silver Bells, a series geared toward the Christmas holidays. While waiting for the sequel to Some Rise by Sin to make itself visible, Courtney has moved into contemporary romance, and A Holiday Wish should be ready by October. Noelle Silver, a wedding planner, considers changing to a different business when her own marital plans go bust right when she’s scouting locations for the ceremony. But a wealthy bride in a hurry just won’t take no for an answer, and before Noelle has time to adjust, she finds herself back in the game, organizing the wedding of the century despite opposition from and the appeal of one very attractive adversary.

Booktrope Editions, an innovative publishing model that ran for five years before I heard of it, announced earlier this month that it is shutting down as of May 31. The authors orphaned by its closing include Joan Schweighardt, who has agreed to re-release her Last Wife of Attila the Hun (possibly under a different title) with Five Directions Press. We look forward to working with her on that project and thank her for entrusting her novel to us. I enjoyed the book, which has won several awards, very much when I read it in January 2016, in preparation for my New Books in Historical Fiction interview with Joan. You can learn more about Joan and this book by listening to her free interview and from “Dealing with the Dragon,” her guest post on this blog.

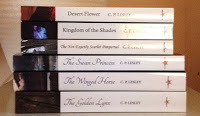

As for other news, don’t forget my own Swan Princess , which came out last month. If you haven’t read any of the Legends novels, you can start with this one, although doing so will undercut some of the suspense in books 1 and 2. So I recommend starting with The Golden Lynx and proceeding through The Winged Horse to the latest installment. I’ve begun work on book 4, The Vermilion Bird, but an onslaught of editing projects has put everything on hold for the last month. Hoping to start up again soon.

Last, but definitely not least, Ariadne Apostolou’s West End Quartet—a set of novellas that follows the fortunes of the women from the urban commune described in her debut novel, Seeking Sophia—should also appear sometime this year. You can read more about West End Quartet and Seeking Sophia , including reading or listening to an excerpt of the latter, by clicking on the title links, which will take you to the Five Directions Press site.

Published on May 13, 2016 08:27

May 6, 2016

Dancing Women

Back in the middle of March, while still immersed in the world of Anjali Mitter Duva’s

Faint Promise of Rain

and Mary Doria Russell’s

Doc

and

Epitaph

, I promised to explore the reimagining of the devadasis into the ballet La Bayadere.

Back in the middle of March, while still immersed in the world of Anjali Mitter Duva’s

Faint Promise of Rain

and Mary Doria Russell’s

Doc

and

Epitaph

, I promised to explore the reimagining of the devadasis into the ballet La Bayadere.I didn’t quite make it, because a ton of things landed on my desk: books for interviews, books for blog posts, my own book in final preparations for release, and projects that had nothing to do with fiction but nonetheless demanded my attention. After a while, I forgot. But today I remembered, and since La Bayadere is a topic close to my heart (I based my Kingdom of the Shades on it, as the title indicates), I decided it was time to pick up the thread.

For reasons that are not entirely clear, Bayadere is not as well known in the West as many other classical Russian story ballets. Choreographed in 1877 by Marius Petipa, the great imperial ballet master, it was a great favorite at the tsar’s court. Often only the third act was performed, and more than one person has written to ask whether I’ve ever heard of the ballet Kingdom of the Shades. But unlike Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and Giselle—even the far less coherent Corsair—Bayadere did not make the leap to the West after the 1917 revolution. The full production arrived only around 1980, when Natalya Makarova staged it for American Ballet Theater.

The plot is typical of nineteenth-century ballets. Nikiya, a temple dancer (devadasi, bayadère) falls in love with a young military hotshot named Solor, who loves her too. But the Brahmin in charge of the temple wants Nikiya for himself. When she refuses, he spies on her with Solor and, beside himself with rage, threatens to kill his rival. Meanwhile, the local Rajah decides to marry his daughter, Gamzatti, to Solor. Solor resists, but what the Rajah wants, he gets. The temple sends Nikiya to bless the young couple, and the Brahmin seizes his opportunity to tattle on Solor to the Rajah. Alas, the Rajah wants to kill Nikiya rather than sacrifice his plans.

When Gamzatti overhears that her husband-to-be wants another woman, she sends for Nikiya and tries to buy her off. Nikiya retaliates by throwing in Gamzatti’s face that Solor has sworn over the temple’s eternal flame to love only Nikiya. The two women get into a catfight and Nikiya runs out, unaware that she now has two people gunning for her: the Rajah and his daughter.

Fast forward to the wedding: celebration and pageantry, a full orientalist display involving everything from elephants to peacocks to a golden idol (even today attended by children in blackface in the Bolshoi production) and a set of wild drummers who may be Gypsies or nomads or something else altogether. The temple, having failed to learn its lesson, again sends Nikiya to dance for the bride and groom. A snake mysteriously appears in a basket of flowers that Nikiya believes come from Solor, and before you know it, Nikiya is bitten. The Brahmin offers her an antidote if she will yield to him, but no. She would rather die than lose Solor.

Distraught and alone, Solor smokes opium. He dreams he has been transported to the Kingdom of the Shades—a garden of ghosts who enter, one by one, down a ramp in ongoing procession. When done properly, this is one of the most stunning entrances in ballet: thirty-two young women in white repeating the same two steps in perfect precision until they all reach the stage and line up. The shades dance in various combinations, then Nikiya appears, and through the course of a long pas de deux she and Solor are reconciled. But he must eventually return to the everyday world and marriage to Gamzatti, while she remains forever beyond his reach. Originally, the ballet finished with a fourth act in which the gods avenge Nikiya’s murder and reunite her with Solor after death. This fourth act can be seen in the Royal Ballet production, but it dropped out of the Russian version of the ballet after the revolution for technical reasons (it involved too many trap doors and pulleys for a cash-strapped state). In emotional terms, the ballet works better without it.

What makes Bayadere interesting despite its old chestnut sensibilities and its rampant orientalism is the triangle at its heart. This is the element I explore in Kingdom of the Shades, and you can find out much more about it in that book. But if we look at it as distorted history, what we see is a Victorian attempt to cope with a very non-Victorian situation. Certain elements of the story have parallels in the lives of real devadasis: the sacred dancer who has a secular patron; the potential for abuse created by that dichotomy; the reality of political marriage and the unlikelihood that a member of the military caste could choose his own wife, especially among the devadasis; the fragility of life. But the story transforms Nikiya into a perfect Victorian maiden, a ghost of the air. She loves and loses in a romantic tale that differs little from those of Giselle and Odette, themselves bowdlerized versions of ancient folklore (for more on Giselle, see my Desert Flower ; The Swan Princess , although it has nothing to do with ballet, draws on another version of the story that gave rise to Swan Lake).

Of course, the devasis, too, had little control over their lives. By the mid-nineteenth century, when Petipa would have heard this story, the older system of patronage, itself unequal, had cracked under pressure from the British Raj. The status traditionally accorded to temple dancers also declined, since the new rulers could not distinguish between sacred women and their sisters on the street. Even the thought of divine dancers probably gave staid colonial moralists hives. Christianity had outlawed dancing in its churches more than a millennium before, precisely because of its appeal to the senses.

In that sense, perhaps Nikiya’s fate is not so inappropriate after all.

Image from Wikimedia Commons. The photograph of the ballerinas dancing the Entrance of the Shades from La Bayadere (2011) was released under a Creative Commons 3.0 license by the photographer, who goes by the name of WhiteAct.

Published on May 06, 2016 06:00

April 29, 2016

Life in Quarantine

As sometimes happens, my latest interview, with Diane McKinney-Whetstone, ended on a thought-provoking note. We were discussing differences as exemplified in her new novel,

Lazaretto

, and the importance of respecting others who are unlike ourselves—indeed, respecting them because they are unlike ourselves.

As sometimes happens, my latest interview, with Diane McKinney-Whetstone, ended on a thought-provoking note. We were discussing differences as exemplified in her new novel,

Lazaretto

, and the importance of respecting others who are unlike ourselves—indeed, respecting them because they are unlike ourselves.At its heart, Lazaretto explores the complexity of race—itself a social, not a scientific construct—and of racial definitions in the United States. Slavery has ended with the Civil War, but late nineteenth-century Philadelphia is still a world where black lives matter less than white ones, where immigrants are feared as harbingers of disease and quarantined to protect the city that does not quite welcome them. The issues are as fresh as yesterday’s headlines, as the current political campaign. Human beings seem to have an innate tendency to settle on insignificant differences that then become the basis for dominance games. We believe that familiarity means sameness, and that sameness will keep us safe.

But in nature, sameness brings death. A population that shrinks in size to the point where it becomes inbred falls victim to birth defects or disease. When the French grapevines failed, almost destroying the wine industry, the solution lay in importing vines from California that could resist the blight and grafting the French stock onto them. In diversity lies strength.

So it makes no sense to fear the other simply because he or she comes from somewhere else or does not look like us in some superficial way. That difference may one day be exactly what we need.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

A hundred years before Ellis Island became a processing center for immigrants wishing to enter the United States, Philadelphia had the Lazaretto, a quarantine hospital where every ship entering the harbor from June to September had to stop while those aboard were checked for signs of infectious disease. In a city already known for its diversity by the mid-nineteenth century, the Lazaretto represented both openness to and fear of the outsider. This deep ambivalence, to change and to the other, forms the heart of Lazaretto (Harper, 2016), the sparkling new novel by Diane McKinney-Whetstone, who already has five acclaimed works of fiction to her credit.

The US Civil War has just ended. In the home of a well-respected midwife, a white attorney has brought his young black servant, Meda, to abort the child he has fathered on her. But the pregnancy is too far along for such a solution, and the child arrives that very night. The father takes the child, ordering the midwife to tell his servant that her daughter is dead. Distraught, Meda takes temporary refuge at a nearby orphanage as soon as she has recovered from childbirth. There she acts as a wet nurse to two newborn boys, whom she christens Bram and Lincoln after her hero, President Abraham Lincoln—assassinated on the same night as her own baby died. When she returns to her employer’s home, the boys come with her for part of every week. Meda raises them as brothers. As the boys grow older, they move back and forth between the affluent white community and the black community of Philadelphia, until a series of drastic events brings them to the Lazaretto. There old questions at last find answers.

Published on April 29, 2016 07:21

April 22, 2016

Flappers and Flickers

A couple of weeks ago, I posted about

Rare Objects

, a new novel by Katherine Tessaro set in Boston during the Great Depression. My latest interview looks at the decades before the stock market collapse of 1929. In 1914, when Olive Thomas moves from Pennsylvania to New York City, prohibition is not yet the law of the land, the theater district is thriving, and what will become the movie industry is just getting started. Europe may soon be at war, but the United States will not join the fray for several years. Meanwhile, a beautiful girl in New York finds her way from shop clerk to artist’s model to dancer with the renowned Ziegfeld Follies. From there, Hollywood beckons, and a silent movie star is born.

A couple of weeks ago, I posted about

Rare Objects

, a new novel by Katherine Tessaro set in Boston during the Great Depression. My latest interview looks at the decades before the stock market collapse of 1929. In 1914, when Olive Thomas moves from Pennsylvania to New York City, prohibition is not yet the law of the land, the theater district is thriving, and what will become the movie industry is just getting started. Europe may soon be at war, but the United States will not join the fray for several years. Meanwhile, a beautiful girl in New York finds her way from shop clerk to artist’s model to dancer with the renowned Ziegfeld Follies. From there, Hollywood beckons, and a silent movie star is born.Poor Olive had to wait yet again for her moment in the sun while I announced the release of The Swan Princess . No doubt, she would consider that par for the course. But her story is, from the beginning almost to the end, tremendous fun, and the time is long past when she should receive an Academy Award of her own.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

A ghost haunts the New Amsterdam Theatre, near Times Square in New York. She wears a green outfit in flapper style, and she’s just a little annoyed to realize that no one is scared of her, even though she mostly rearranges the scenery rather than clanking chains or leaping out and scaring people. Her name is Olive Thomas, and she is one of the first silent movie stars, although her early death means that she is much less famous than her sister-in-law, Mary Pickford.

Born near Pittsburgh, Olive moves to New York to escape a teen marriage and a life raised in poverty. After winning a contest as the Most Beautiful Girl in New York, she becomes an artist’s model before securing a position with Flo Ziegfeld, the mogul behind the Follies. Ziegfeld takes a shine to Olive, and soon she is not only dancing for him but has become a regular in the much racier Midnight Follies. Before long, she and Ziegfeld are involved in an affair, but when Ziegfeld goes back to his wife, Olive takes off for Hollywood. In Santa Monica, she runs into Jack Pickford, Mary’s younger brother, and discovers her kindred spirit. To the great distress of his family, the two of them drink and party their way around movie sets on both coasts. Over the course of four years, Olive makes twenty films, including The Flapper—the film that introduced that term into the national lingo. Then she and Jack decide to vacation in Paris …

The Forgotten Flapper: A Novel of Olive Thomas (Sepia Stories, 2015) brings this forgotten actress back to life. Laini Giles vividly captures both the culture of those early days when films were still called “flickers” and Olive Thomas’s complex, charming, and compelling personality. The ostrich scene alone is—dare we say it?—unforgettable.

Published on April 22, 2016 06:00

April 15, 2016

The Swan Princess

Twenty-two months after I sat down to write, Five Directions Press has released The Swan Princess (Legends 3) in print and Kindle e-book. For some reason Legends 3 gave me fits, but after a few false trails I found the story and after that, it was pure bliss to write.

Twenty-two months after I sat down to write, Five Directions Press has released The Swan Princess (Legends 3) in print and Kindle e-book. For some reason Legends 3 gave me fits, but after a few false trails I found the story and after that, it was pure bliss to write. What made Legends 3 so tough in the beginning? Well, first off, it is the middle of the series. Middles of books are difficult, because the setup is done, but the resolution cannot begin, so authors need to find a way to sustain the momentum without resolving the major plot threads and character arcs too soon. It’s the same with a series. Then there were the characters, whom I created and love but who must be just a bit farther along their journey to maturity—although not so far that their growth seems implausible or their basic natures changed. A third factor was the Swan Princess herself: the metaphor came to me right away, but figuring out the story indicated by the legend took much longer. In what sense was Nasan a swan princess? What did she need to learn? What circumstances would teach her? How would I keep the new story separate from the old? What role would the political backdrop play in this fundamentally domestic tale?

But that, after all, is what novelists do. And now that I am moving on to book 4, and the phoenix has replaced the swan as my image of choice (but book 4 is already on the down slope of the series), I am looking forward to reconnecting with another set of characters and exploring a new political story and metaphor. I hope it won’t take twenty-two months—but if it does, I expect to enjoy the journey.

In the meantime, I hope you have fun with Nasan and her relatives. And if by chance you encounter her first here, do go back and read her earlier adventures. In honor of the formal launch on Friday, the e-book versions of Legends 1 and 2 will be on sale for 99 cents (US, 99p UK) from April 15 through April 17. So if you missed The Golden Lynx and The Winged Horse , this is your chance to give them a try at low cost. To find out more about Legends 3, read on.

THE SWAN PRINCESS

In the two years since the events that propelled Nasan Kolycheva into marriage to a Russian nobleman, life has become intolerable. She spends every waking minute learning the skills of household management under the lash of her sister-in-law’s tongue and the cloud of her mother-in-law’s disappointment while mourning her unborn baby and pining for her husband, stationed in the western borderlands to ward off foreign invaders.

When Nasan’s mother-in-law decides that a pilgrimage to a distant monastery may be the only solution for her failing heart, the journey sparks memories in Nasan of a life she has almost forgotten, where her interests and skills serve a purpose lost to her in Moscow. What can a Swan Princess do when she no longer wants to return to the nest? Before Nasan can answer that question, she encounters a once-vanquished foe determined to avenge himself on those he blames for his misfortunes—and realizes she has ridden right into his trap.

INITIAL REVIEWS

“Lyrical and compelling, The Swan Princess draws the reader into the world of sixteenth-century Russia, a world unfamiliar to many readers, which becomes vividly real in the hands of this master storyteller. The characters of Nasan, Daniil, and the others leap off the page. Perhaps most intriguing is the portrayal of the clash between the two vibrant but alien cultures of the Russians and the Tatars—frequently at war, occasionally bound by an uneasy and watchful peace.”—Ann Swinfen, author of Voyage to Muscovy

“An action and suspense-infused historical adventure that kept me turning the pages right to the end. The characters are so well-drawn, the historical facts so cleverly woven into the narrative, time and place so brilliantly evoked, I felt I was experiencing sixteenth-century Russia firsthand.”

—Liza Perrat, author of the Bone Angel Trilogy

“C. P. Lesley directs her cast of fictional and historical characters with an authority that can only come from a fervent understanding of the cultures and values of the times. With deft strokes she brings the characters fully to life—revealing their psyches and the depths of their motivations—without ever impeding the pace of the story. The Swan Princess is a beautifully written, perfectly balanced historical novel by an author who knows her stuff and has mastered her craft.”

—Joan Schweighardt, author of The Last Wife of Attila the Hun

EXCERPT

South of Pechenga, February 1536

Sleet stung his face. Brother Stefan tugged the rabbit-skin hat over his ears and turned up the collar of the worn fur coat—a gift to the monastery, no doubt, from some half-starved priest determined to secure prayers for his soul. Shivering, he squinted through ice-crusted eyelashes at an oval of red topped by a semicircle of bright blue. Against the white/gray Arctic landscape, the patch of color sufficed to identify the Lapp herder guiding his rickety sleigh across the tundra.

“Can’t that beast go faster?” Stefan kicked the front of the sleigh and chided himself for impatience—in vain. His demand for speed was irrational. He’d secured permission for his journey. No one would follow him in this blizzard. He had nothing to fear, yet his whole body urged him to press on, beat the reindeer—or the driver—if necessary. Whatever would increase the distance between himself and that godforsaken excuse for a monastery. He’d wasted months there already.

Getting out of the Arctic blast would be a blessing, but no hope of that for a few more weeks—unless this slug of a reindeer grew wings and took to the air. What a sight that would be!

Off to one side, through the driving sleet, he saw a small hut raised on logs, two of its chicken feet buried up to the ankles in snow, the front two swept bare by the circling winds. It looked like the home of the witch Baba Yaga, terror of his nursery days.

He shivered again—and not from the cold. How could one know, dashing past in a reindeer-drawn sleigh, whether a witch dwelled there?

He shivered again—and not from the cold. How could one know, dashing past in a reindeer-drawn sleigh, whether a witch dwelled there?Bridge and bears play an important role in the story (bridge iStock 509320443; bears © Gledriius/Shutterstock 173103809).

Published on April 15, 2016 06:00

April 8, 2016

Upward Mobility

It’s 1932, and the world is struggling through the Great Depression. Maeve, a young Irish immigrant, has just returned from New York, where her failure to find a secretarial job has led her into a web of lies, scandal, and alcohol that has landed her in a mental hospital. There she makes friends with a patient who stands out from the others; then Maeve’s enforced stay in the hospital ends, and she decides to leave New York and its bitter past behind.

It’s 1932, and the world is struggling through the Great Depression. Maeve, a young Irish immigrant, has just returned from New York, where her failure to find a secretarial job has led her into a web of lies, scandal, and alcohol that has landed her in a mental hospital. There she makes friends with a patient who stands out from the others; then Maeve’s enforced stay in the hospital ends, and she decides to leave New York and its bitter past behind.Back in her mother’s home in Boston’s North End, Maeve is still searching for work. A chance encounter with a hiring service leads her to an antique shop where the owner needs an assistant—but the Irish need not apply. Maeve bleaches her red hair to blonde, becomes May (“with a y”) from Albany, and through her job in the shop mixes with Boston’s upper crust. One evening, a delivery brings her face to face with Diana, her friend from the asylum, and she becomes drawn into a strange and glittering world as far removed from her childhood apartment as it is from the poverty that afflicts much of the country. Diana’s brother, James, takes an interest in his sister’s new friend, and Maeve’s innocent deceit soon threatens to spin out of control.

In clear and unflinching prose, Kathleen Tessaro recreates the world of Depression-era Boston, both among the Brahmins and amid the Irish, Italian, and Jewish immigrants who occupied various parts of the city. Maeve’s struggle to define herself and her values despite the temptations of wealth and bootleg gin is compellingly and compassionately portrayed. This is a journey well worth following.

Kathleen Tessaro is the author of six novels—Elegance, Innocence, The Flirt, The Debutante, The Perfume Collector, and Rare Objects , which will be released on April 12. Harper Collins, her publisher, sent me a copy of Rare Objects with a request for an interview, but because I am booked through July, we agreed that I would write this blog post instead. You can find out more about Kathleen and her books at http://www.kathleentessaro.com.

Published on April 08, 2016 06:00

March 30, 2016

Party All the Time

Or, The Joys of Writing Historical Fiction

First off, my thanks to Joan Schweighardt for coming up with this idea and to Anjali Mitter Duva and Kristen Harnisch for agreeing to take part. The essence of the plan is that each of us writes a longer blog post on her own, as well as a 250-word summary that we will publish as a group. Normally, I would post my entry on Friday, but this Friday is April Fool’s Day—and when it comes to writing historical fiction, I’m not fooling. Hence the atypical Wednesday post.

First off, my thanks to Joan Schweighardt for coming up with this idea and to Anjali Mitter Duva and Kristen Harnisch for agreeing to take part. The essence of the plan is that each of us writes a longer blog post on her own, as well as a 250-word summary that we will publish as a group. Normally, I would post my entry on Friday, but this Friday is April Fool’s Day—and when it comes to writing historical fiction, I’m not fooling. Hence the atypical Wednesday post.

So what are the joys of writing historical fiction, from my perspective? I see many, but I’ll focus on three: familiarity, research, and escapism (mine and the readers’).

Familiarity

“Write what you know”—it’s a cliché. But it doesn’t always mean write about your home town or the life you experienced as a child, never mind thinly disguised versions of your current friends and office mates (who may not remain friends and colleagues if they read your fictional take on them). History is what I know—Russian history in particular. Long before it became my profession I loved to study it, to read novels based on it, to write essays of my own. For decades, I did not intend to write fiction of my own, but once I did stumble onto the idea for a novel, the lure of my chosen historical field—so rich and so foreign to most people in the West—made it the logical choice for my novels as well. Noblemen and peasants, bandits and warriors, blood feuds and raids, coups and invasions and arranged political marriages: was there ever a place more naturally dramatic than Russia? Half the time, I don’t even have to make things up (although that’s fun, too)!

Research

Of course, research is work. Many authors don’t like it—although more do than you might expect if you have never attempted historical research yourself. For me, it’s what I do, even when I’m not writing novels. And research for a novel is different from researching an academic article. I don’t have to master (or appear to have mastered) all the existing literature or spend years in the archives; I don’t need to produce an academically defensible position that gives due credit to those who came before while sketching out an argument that is uniquely my own. But I do need to create a plausible world filled with characters who belong in that world, which means immersing myself in all kinds of details of everyday life and—more important—learning about the specific ways in which different types of people thought about the world, themselves, and their place in the universe. Researching a novel can be frustrating—even in the Age of the Internet, a novelist can’t always uncover essential details of clothing or utensils or even food and drink, never mind smells and tastes—but it can also be tremendous fun. When I stumbled over the tale of Abbot Trifon of Pechenga’s bandit past, for example, I couldn’t wait to include it in The Swan Princess. I had to redo the entire plot of my novel in progress, but I wouldn’t have missed that opportunity for anything.

Escapism

Here I have in mind several related meanings of the word. Most obviously, escaping into a previous century in a distant place offers relief from everyday worries and troubles for both readers and writers. But the escape into history also opens up possibilities for fiction that our technologically sophisticated modern world has closed down. Yes, human emotions have not changed for millennia; only the cultural constraints that provoke specific emotions vary from one place and time to another. And placing oneself in another’s shoes, whatever the time period, holds out the potential for enjoyment; the modern world is not uniform, and even today we see many different philosophies in play, have many chances to experience the viewpoints of fictional people unlike ourselves. Contemporary life contains plenty of space for rage, resentment, grief, agony, and that life blood of fiction, misunderstandings.

But strip the world of cellphones, computers, DNA tests, police and fire protection, NSA-type security, and even basic literacy—never mind such things as respect for women and minorities—and a writer acquires many more options for spreading confusion and stoking the fires of conflict. Characters can disappear into the woods, take justice into their own hands, lie about their paternity (or even maternity), raze cities to the ground, retire to monasteries, force their children into marriage, impersonate dead rulers, consult witches and sorcerers, poison their enemies with untraceable toxins, leave fingerprints that no one knows can identify them, and much, much more. Letting one’s imagination roam free is cathartic, and so long as it remains on the page, it does little harm.

I could go on, but those are three great pleasures of writing historical fiction for me. What makes historical fiction special for you?

For the others’ posts, see “Spelunking from My Desk, Or Why I Love Writing Historical Fiction” (Joan), “Reaching the Pinnacle of Joy and Wonder in Historical Research: A Six-Part Swimming Metaphor” (Anjali), and “Writing the Past: The Devil Is in the Details” (Kristen). And while you’re there, don’t forget to check out their books!

First off, my thanks to Joan Schweighardt for coming up with this idea and to Anjali Mitter Duva and Kristen Harnisch for agreeing to take part. The essence of the plan is that each of us writes a longer blog post on her own, as well as a 250-word summary that we will publish as a group. Normally, I would post my entry on Friday, but this Friday is April Fool’s Day—and when it comes to writing historical fiction, I’m not fooling. Hence the atypical Wednesday post.

First off, my thanks to Joan Schweighardt for coming up with this idea and to Anjali Mitter Duva and Kristen Harnisch for agreeing to take part. The essence of the plan is that each of us writes a longer blog post on her own, as well as a 250-word summary that we will publish as a group. Normally, I would post my entry on Friday, but this Friday is April Fool’s Day—and when it comes to writing historical fiction, I’m not fooling. Hence the atypical Wednesday post.So what are the joys of writing historical fiction, from my perspective? I see many, but I’ll focus on three: familiarity, research, and escapism (mine and the readers’).

Familiarity

“Write what you know”—it’s a cliché. But it doesn’t always mean write about your home town or the life you experienced as a child, never mind thinly disguised versions of your current friends and office mates (who may not remain friends and colleagues if they read your fictional take on them). History is what I know—Russian history in particular. Long before it became my profession I loved to study it, to read novels based on it, to write essays of my own. For decades, I did not intend to write fiction of my own, but once I did stumble onto the idea for a novel, the lure of my chosen historical field—so rich and so foreign to most people in the West—made it the logical choice for my novels as well. Noblemen and peasants, bandits and warriors, blood feuds and raids, coups and invasions and arranged political marriages: was there ever a place more naturally dramatic than Russia? Half the time, I don’t even have to make things up (although that’s fun, too)!

Research

Of course, research is work. Many authors don’t like it—although more do than you might expect if you have never attempted historical research yourself. For me, it’s what I do, even when I’m not writing novels. And research for a novel is different from researching an academic article. I don’t have to master (or appear to have mastered) all the existing literature or spend years in the archives; I don’t need to produce an academically defensible position that gives due credit to those who came before while sketching out an argument that is uniquely my own. But I do need to create a plausible world filled with characters who belong in that world, which means immersing myself in all kinds of details of everyday life and—more important—learning about the specific ways in which different types of people thought about the world, themselves, and their place in the universe. Researching a novel can be frustrating—even in the Age of the Internet, a novelist can’t always uncover essential details of clothing or utensils or even food and drink, never mind smells and tastes—but it can also be tremendous fun. When I stumbled over the tale of Abbot Trifon of Pechenga’s bandit past, for example, I couldn’t wait to include it in The Swan Princess. I had to redo the entire plot of my novel in progress, but I wouldn’t have missed that opportunity for anything.

Escapism

Here I have in mind several related meanings of the word. Most obviously, escaping into a previous century in a distant place offers relief from everyday worries and troubles for both readers and writers. But the escape into history also opens up possibilities for fiction that our technologically sophisticated modern world has closed down. Yes, human emotions have not changed for millennia; only the cultural constraints that provoke specific emotions vary from one place and time to another. And placing oneself in another’s shoes, whatever the time period, holds out the potential for enjoyment; the modern world is not uniform, and even today we see many different philosophies in play, have many chances to experience the viewpoints of fictional people unlike ourselves. Contemporary life contains plenty of space for rage, resentment, grief, agony, and that life blood of fiction, misunderstandings.

But strip the world of cellphones, computers, DNA tests, police and fire protection, NSA-type security, and even basic literacy—never mind such things as respect for women and minorities—and a writer acquires many more options for spreading confusion and stoking the fires of conflict. Characters can disappear into the woods, take justice into their own hands, lie about their paternity (or even maternity), raze cities to the ground, retire to monasteries, force their children into marriage, impersonate dead rulers, consult witches and sorcerers, poison their enemies with untraceable toxins, leave fingerprints that no one knows can identify them, and much, much more. Letting one’s imagination roam free is cathartic, and so long as it remains on the page, it does little harm.

I could go on, but those are three great pleasures of writing historical fiction for me. What makes historical fiction special for you?

For the others’ posts, see “Spelunking from My Desk, Or Why I Love Writing Historical Fiction” (Joan), “Reaching the Pinnacle of Joy and Wonder in Historical Research: A Six-Part Swimming Metaphor” (Anjali), and “Writing the Past: The Devil Is in the Details” (Kristen). And while you’re there, don’t forget to check out their books!

Published on March 30, 2016 09:29

March 25, 2016

First, but Not Equal

Empresses, regents, royal mistresses, twentieth- and twenty-first-century politicians—the life of women in power has seldom been easy. Whether we have in mind Elena Glinskaya, ruling as the mother of Ivan the Terrible (then aged three through seven); Sophia, regent for her younger brothers Ivan and Peter (later self-styled the Great); the eighteenth-century Russian empresses from Catherine I to Catherine II (another “Great”); Catherine de Médicis, Diane de Poitiers, and Mmes de Pompadour and de Montespan in France; Mary Tudor and her sister Elizabeth as queens of England; or Hillary Clinton on yesterday’s news, authoritative women have been viewed as bossy or shrewish, immoral or murderous, manipulative or inclined toward witchcraft, depending on the time period.

Empresses, regents, royal mistresses, twentieth- and twenty-first-century politicians—the life of women in power has seldom been easy. Whether we have in mind Elena Glinskaya, ruling as the mother of Ivan the Terrible (then aged three through seven); Sophia, regent for her younger brothers Ivan and Peter (later self-styled the Great); the eighteenth-century Russian empresses from Catherine I to Catherine II (another “Great”); Catherine de Médicis, Diane de Poitiers, and Mmes de Pompadour and de Montespan in France; Mary Tudor and her sister Elizabeth as queens of England; or Hillary Clinton on yesterday’s news, authoritative women have been viewed as bossy or shrewish, immoral or murderous, manipulative or inclined toward witchcraft, depending on the time period. This uncomfortable truth holds even when the men who were the lovers or husbands of these female rulers were corrupt, insane, or otherwise incompetent. Our modern world may be more comfortable with women in power, but the double standard still exists. Imagine, then, the obstacles that faced the Tang Dynasty concubine Wu Mei (Wu Zetian), who defied every Confucian principle and restriction to become the only empress in Chinese history to rule without a husband as figurehead. Under her guidance, women achieved property rights and an education, and the kingdom flourished, buoyed by the silk trade with the west. She died in 705, and the Zhou dynasty she founded died with her, becoming a mere interregnum in the longer arc of the Tang.

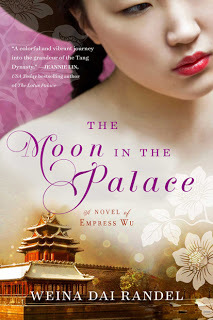

It is a compelling tale, and it makes for a fitting entry in my blog series on women in history, revived two weeks ago in “The Divine and the Disrespected” (note that last week’s post also discusses women in World War I). But for the full story of Empress Wu and her times, listen to my interview with Weina Dai Randel and, most of all, read her novels. You can find links to them below.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

In four thousand years of Chinese history, Empress Wu stands alone as the only woman to rule in her own name. She died in her eighties after decades of successful governance, but her sons could not hold the kingdom she established for them and the dynasty she founded soon fell from power. The Confucian scholars who recorded her history—outraged by the idea of a woman ordering men—depicted her as a murderous, manipulative harlot, an image that has ever since obscured her achievements. In The Moon in the Palace (Sourcebooks, 2016), Weina Dai Randel seeks to polish Empress Wu’s tarnished reputation, offering a new look at her and her times, the obstacles she faced and the gifts that enabled her to overcome them.

Wu Mei is five years old when a Buddhist monk predicts her future as the mother of emperors and bearer of the mandate of Heaven. By thirteen, she has already entered the Imperial Palace as a Select, one of a small group of maidens chosen to serve the Taizong Emperor. But the palace is a vast and complex hierarchy, and Mei one untried girl among the two thousand women it contains. Her first friend betrays her trust, her emperor has little use for her, and his youngest son seems all too willing to pay her the attention that his father withholds. Meanwhile, intrigue within the palace threatens the emperor and all those who depend on him. In this poisonous atmosphere, even a junior concubine may find it difficult to keep her head. Mei, capable and smart, is not easily daunted, but she worries that she will soon find herself out of her depth.

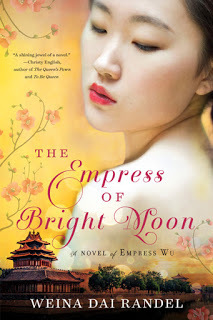

Mei’s story continues in The Empress of Bright Moon , due for release in early April 2016. In both novels, Randel paints in rich and compelling prose a wonderfully believable and nuanced portrait of a long-vanished court and the young woman who must navigate its treacherous paths.

Published on March 25, 2016 07:18

March 18, 2016

Remembering the Great War

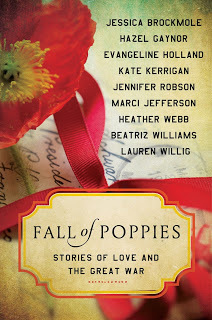

Fall of Poppies: Stories of Love and the Great War

is one of several great books sent to me for potential interviews that I just couldn’t fit into my schedule. I was delighted when the editor, Heather Webb, agreed to a blog interview instead. The results are below, with my questions in bold and her answers following. But don’t stop here: the stories, too, are well worth your time.

Fall of Poppies: Stories of Love and the Great War

is one of several great books sent to me for potential interviews that I just couldn’t fit into my schedule. I was delighted when the editor, Heather Webb, agreed to a blog interview instead. The results are below, with my questions in bold and her answers following. But don’t stop here: the stories, too, are well worth your time.Want to be sure? You can read a sample story on your Kindle, if you have one, for 99 cents: Lauren Willig’s “The Record Set Right.”

What is the impetus behind this project? Where did the idea come from?

I noticed an upswing in anthologies and it got the wheels turning. Why couldn’t there be one based on a historical event or theme, I asked myself. As a big Downton Abbey fan, I kept thinking I’d like to read more set during the Edwardian era, so I began brain-storming ideas and eventually wrote the pitch, which is the cover copy you see.

The goal of the stories was to portray the various forms of love—and loss—of citizens of Europe who suffered through World War I and, above all, tie these themes to a sense of hope. Ultimately, people need nothing more than hope in this world; to carry on, to get to the other side—to achieve, even. I thought the contributors did a terrific job of illustrating this basic human need.

How did you select authors for inclusion?

I did a little research on historical authors who had published novels or were currently working on projects that revolved around WWI already. A couple of the authors said, “Hey, I’d love to, and can I ask my friend XXX, too?” I agreed readily after taking a look at their biographies. The authors were eager and excited to try a new type of project.

Each of the stories deals in some way with the moment when the Armistice in what was then known as the Great War (World War I) took place. Some occur years later, others in the hours leading up to the battle—and a third group does both. Why pick that moment as the common thread for the book?

Armistice Day—the end of the Great War—paved the way for the modern world as we know it. Before the war, the western world had grown at a rapid rate with new transportation infrastructures and mechanization, thereby expanding the middle class and creating a working poor. All were living in a time of romanticism, in which all seemed possible and beautiful. The Beautiful Era or Belle Époque in France. The vast majority of society had gone a little soft around the edges. It had been one hundred years since the last major war. When the war began, men went off to prove their honor, to “become men again,” and not these metropolitan fellows, saturated with plenty of food and diversions. But so many things happened they didn’t expect—advancements in weaponry, including chemical warfare, barbed wire, and machine guns; and vacancies in the job sector at home, bringing women to the forefront of society, as well as triggering the collapse of the class system. It was a new world, for better or worse. This was the beginning of the world we live in today.

I can hardly think of a more interesting, and still relevant, topic to explore.

Tell us a bit about your own contribution, “Hour of the Bells.” Where does the story come from and how does it fit into your work as a whole, if it does?

As a cultural geographer and former military brat, I find myself perpetually fascinated by the idea of “the outsider” within a culture not their own, what it means to belong, and how our values and ideals can shift as we assimilate. Beatrix is a German-born woman who married a Frenchman and their only son is ridiculed for being a dirty “boche,” spurring him to join the war efforts. When her son perishes, she can’t forgive herself for who she is and how she has failed him—and sets out on a quest for vengeance, to prove her love. The story has a very cinematic quality to it, ultimately, which I was aiming for as I plotted the themes. I couldn’t think of a more powerful motivation than a mother’s love and grief.

The anthology focuses on themes of love in its various forms from lovers to friends, to parents and their children. In “Hour of the Bells,” I explore the love between mother and son as well as woman and country.

The anthology focuses on themes of love in its various forms from lovers to friends, to parents and their children. In “Hour of the Bells,” I explore the love between mother and son as well as woman and country. Thank you, Heather!

Heather Webb is the author of Becoming Josephine and Rodin’s Lover , as well as the editor of and a contributor to Fall of Poppies: Stories of Love and the Great War. You can find out more about her and her books at her website.

Published on March 18, 2016 06:00

March 11, 2016

The Divine and the Disrespected

Back in 2013, I wrote a series of posts on women in history. It began with “Women of Steel” and continued through “Taking the Veil,” with a brief follow-up in “The Kremlin Beauty Pageant.” That last post looks at marriage politics, a crucial feature of my Legends of the Five Directions novels—indeed, one of the reasons for the existence of that series, as the Muscovite elite’s use of marriage politics has become generally accepted within my field but remains largely unknown outside it. (For the other posts, start with “Taking the Veil,” and you can follow them back, one by one.)

Back in 2013, I wrote a series of posts on women in history. It began with “Women of Steel” and continued through “Taking the Veil,” with a brief follow-up in “The Kremlin Beauty Pageant.” That last post looks at marriage politics, a crucial feature of my Legends of the Five Directions novels—indeed, one of the reasons for the existence of that series, as the Muscovite elite’s use of marriage politics has become generally accepted within my field but remains largely unknown outside it. (For the other posts, start with “Taking the Veil,” and you can follow them back, one by one.)Ancient history, you may think, both literally and figuratively. But when I wrote about Anjali Mitter Duva’s Faint Promise of Rain , followed in short order by Mary Doria Russell’s Doc and Epitaph, I realized I had left out one major path by which women found their own way in the world when other means failed them: the option of servicing men without marriage. There is a reason why prostitution is called “the world’s oldest profession”: it’s been around since the time of Sumer, at least, and began under circumstances not unlike those described in Faint Promise of Rain. Even the Old Testament mentions it.

Nevertheless, the world that Adhira enters in Faint Promise of Rain is quite different from Doria Russell’s Wild West. Adhira becomes a devadasi, a temple dancer (in an unexpected coincidence, the Western term for a devadasi is bayadere, as in the ballet that forms the backdrop to my Kingdom of the Shades—more on that soon). The devadasis are married to the god to whom their temple is dedicated. At the same time, powerful male patrons pay for their support, and the devadasis are required to satisfy their patrons’ sexual demands. As a result, these women are simultaneously revered for their connection with the divine and victimized. When the British arrive on the scene, with their Victorian sensibilities, they cannot see the difference between the temple dancers and the “loose” women they left behind in London, and the dancers’ status quickly declines.

One might say that it declines to the level of the saloon girls in the Wild West, so richly portrayed in Doc and Epitaph. But their situation, too, turns out to be more complex than it first appears. Kate Harony, Doc Holliday’s long-time if inconstant lover, and Josie Marcus, who married (or did she?) Wyatt Earp, both spent time in the brothels of Dodge City, Tombstone, and elsewhere. Josie’s stint in prostitution was short, but she lived with one Tombstone politician before taking up with Wyatt Earp, who was living with another woman at the time. Kate practiced the oldest profession for decades, including during her relationship with Doc, before marrying someone else after Doc’s death. She had little choice, despite speaking numerous languages and possessing a classical education; when she was orphaned at fifteen, she had no other means of support. Yet Josie and Kate and the other Earp women moved in and out of the sex trade, alternating with periods as common-law wives and mistresses and sometimes legal spouses.

This is the seamy side of women’s history, long brushed under the rug except for the royal favorites who enliven any history of medieval and early modern Europe. But Kate’s story shows why we ignore it at our peril. For so much of history, women have depended on husbands and fathers for their support. Prevented from acquiring professional skills, often forbidden to work except in certain low-paid and low-status occupations, and despised for using what they have, should they be so unlucky or so unwise as to fall out of the socially approved nest, they have done whatever they could to make ends meet. There was no state-supported social welfare program, so the alternative was the poor house— if it existed, which it did not in the Wild West—or starvation. Alms from churches and monasteries did little to offset the reality of poverty and in any case ceased after the Reformation to be a significant source of aid.

This is the seamy side of women’s history, long brushed under the rug except for the royal favorites who enliven any history of medieval and early modern Europe. But Kate’s story shows why we ignore it at our peril. For so much of history, women have depended on husbands and fathers for their support. Prevented from acquiring professional skills, often forbidden to work except in certain low-paid and low-status occupations, and despised for using what they have, should they be so unlucky or so unwise as to fall out of the socially approved nest, they have done whatever they could to make ends meet. There was no state-supported social welfare program, so the alternative was the poor house— if it existed, which it did not in the Wild West—or starvation. Alms from churches and monasteries did little to offset the reality of poverty and in any case ceased after the Reformation to be a significant source of aid. Yet society’s condemnation was harsh. The “whores” who trailed in the wake of the early modern European armies were, for the most part, women who remained faithful to one soldier—who washed his clothes, prepared his food, bore his children, and fought for his interests—but who lacked a wedding ring or a church record confirming their relationship. We are fortunate to live in a time and place when our options, if not infinite, are much greater than our foremothers’. Let us not forget how difficult a woman’s life can be, even today.

All images from Wikimedia Commons. Friedrich Schoberl’s drawing of the devadasis (1820s) and the photographs of Kate Harony at fifteen with her sister (Kate is the one seated, ca. 1867) and Josie Marcus at twenty (1881, taken in Tombstone by C. S. Fly) are in the public domain in the United States because they were produced before 1923.

Published on March 11, 2016 07:52