C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 46

August 7, 2015

Book Muse Recommended Read

I did know this was in the works, but even so, it was a delightful surprise to log on this morning and learn that Liza Perrat had posted this great review of The Winged Horse. Many thanks, Liza, and I display my Book Muse Recommended Read badge with pride!

I did know this was in the works, but even so, it was a delightful surprise to log on this morning and learn that Liza Perrat had posted this great review of The Winged Horse. Many thanks, Liza, and I display my Book Muse Recommended Read badge with pride!  Check out Liza’s website for information on her books, listed below. Book 3 of her Angels series should also be available soon.

Check out Liza’s website for information on her books, listed below. Book 3 of her Angels series should also be available soon.Reviewer: Liza Perrat, author of Spirit of Lost Angels and Wolfsangel.

What we thought: Like C.P. Lesley’s first book, The Golden Lynx, of her Legends of the Five Directions series, the author once again brings to life 16th-century Russia via a Mongol horde, in this exciting tale of marriage, murder, and mysticism.

Upon his deathbed, Bahadur Bey, leader of a horde of nomadic Tatars, makes the clan leaders swear to accept Ogodai, son of his blood brother Bulat Khan (descendent of Genghis Khan), as the horde’s new overlord. It is also agreed that Bahadur Bey’s daughter, Firuza, will become Ogodai’s chief wife.

Tulpar, Bulat’s estranged son, arrives on the scene and attempts to stake claim to the horde and also to Firuza. The conflict, plotting, and intrigue begins: brother against brother in a struggle for both power and wife.

Firuza, no great beauty but determined and intelligent, can choose either Ogodai or Tulpar, but the man who wins her must also accept her on an equal footing. Firuza’s struggle evokes the feisty women of this era, who refused to be treated as pawns, preferring to control their own destiny.

The Winged Horse sweeps the reader five centuries into the past in a well-told and swiftly paced tale rich with culture and evocative description. It is also a tale of romance, and of horses. Amongst other horse lore, there is Firuza’s Turkmen palomino and Tulpar, the winged horse, who carried dying souls to the celestial hunting grounds.

As with C. P. Lesley’s first book in this series, I have once again thoroughly enjoyed learning more about the Tatars of 16th-century Russia, and I would highly recommend The Winged Horse to historical fiction fans.

You’ll enjoy this if you like: murder mysteries and tales of romance and adventure that feature strong women, wrestling, horse races, and an Arabic-chanting shaman dressed in ragged skins.

Avoid if you don’t like: action-packed, fast-paced historical political intrigue.

Ideal accompaniments: hot soup (şulpa) washed down with a large glass of vodka.

Genre: Historical Fiction.

For this review and many other ideas for novels to add to that groaning to-be-read pile, make regular visits to the Book Muse site. Tell them I sent you. Just don’t pelt me with all those lovely new books....

Published on August 07, 2015 06:00

July 31, 2015

Casting Call

I can’t be the only novelist who fantasizes about one day seeing her characters romping around on the silver screen. It’s a joke, of course, so long as I continue to sell just about enough books to keep myself in coffee, but what’s the point of being a writer if you can’t make stuff up? Besides, because I approach the world from the perspective of an intensely visual person—even my story ideas begin as images in my head—casting my characters has become an important step in getting myself ready to write.

I work full-time, you see, on other things—and although I always plan to put in an hour or so at the end of each workday, too often I don’t get through an article on schedule or someone writes at 4 PM desperate for a file or a book or information only I can provide. As a result, every Friday requires me to reorient myself to my current characters and story. These blog posts offer a pathway for making that transition (one reason I update the blog each Friday). Editing previously written scenes and researching new ones also pull me back into the current book.

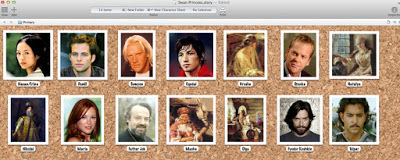

A third method involves pictures: photographs, paintings, maps that represent my characters, settings, or plot points. As I mentioned last year in “The Technology of Writing,” one of the main things I love about the novel-writing program Storyist is that it lets me see my characters or settings as Polaroids pinned on a cork board while I’m writing. I choose paintings for many of the minor characters, especially the wonderful historical paintings of Konstantin and Vladimir Makovsky, some of which also appear on this blog. But for the major characters I choose actors, even though I am well aware that if my novels ever do give rise to screenplays, authors do not get to pick their own casts.

Since I first saw Chris Pine in the 2009 Star Trek reboot, I have imagined him as Daniil, hero of The Golden Lynx and my work-in-progress The Swan Princess. He has the right look and, more important, the right devil-may-care attitude. But since sixteenth-century Russian noblemen did not run around in Star Fleet uniforms, for years I relied on pictures of Henry Cavill as Charles Brandon in The Tudors (also a worthy contender for the role of Daniil!). Still, it made my day when, while procrastinating—er, priming the creative pump—on the Internet, I discovered screen shots of Chris Pine as Cinderella’s Prince Charming in Into the Woods. More eighteenth century than sixteenth, but close enough. At one point, he’s even riding a horse. The joy of my weekend, thanks to a Netflix subscription, will be watching Prince Charming in action.

Here the poor man is about to get the boot (I think, based on the plot summary) from Anna Kendrick—who, although not my idea of Nasan, could be her in this particular shot. Woods play a big part in The Swan Princess, as one would expect in a novel set in the Russian North, and the dim light turns the actress’s hair to black, rather than its natural brown.

By the time The Golden Lynx finds its director, if it ever does, Pine will, alas, be too old for Daniil, who is nineteen at the beginning of the series and no more than twenty-five by the end. Some other as yet unknown young hot shot will have to take on the role. But for now, Captain Kirk will do just fine.

Images: Screen shots of my working file for The Swan Princess and from Into the Woods (2014).

Published on July 31, 2015 07:05

July 24, 2015

Stone of Destiny

I must confess that, even though my heritage is 100% Scots, my interest in history has rarely extended to the land of my ancestors. Except for Dorothy Dunnett’s Lymond Chronicles, most of which take place outside Scotland, Marie Macpherson’s evocative The First Blast of the Trumpet (about John Knox), and the occasional Highland romance of a misspent youth, I rarely even read fiction set in Scotland.

I must confess that, even though my heritage is 100% Scots, my interest in history has rarely extended to the land of my ancestors. Except for Dorothy Dunnett’s Lymond Chronicles, most of which take place outside Scotland, Marie Macpherson’s evocative The First Blast of the Trumpet (about John Knox), and the occasional Highland romance of a misspent youth, I rarely even read fiction set in Scotland.This response grows out of a sense, true or false, that Scottish history stops being depressing right around the time when the Stuarts take the English crown in 1603. The thirteenth century, when the clans couldn’t stop bickering long enough to keep William Wallace from a grisly execution or even agree on a king, was a particularly dark time. Yet when Glen Craney wrote to me to propose a New Books in Historical Fiction interview about his novel The Spider and the Stone—based on the life of James Douglas, the man whose steadfast support for Robert the Bruce secured Scotland’s independence for a few more centuries—I decided I really should read the book. I had, after all, grown up on stories of the Bruce and the spider in the cave, as well as tales of Edward I’s confiscation of Scotland’s coronation stone and its attempted recovery in 1950.

And I’m glad I did—read the book, that is. It’s a fun read and includes a twist that I won’t reveal about the Stone of Scone (pronounced Skoon, by the way) that fit wonderfully within the world of the story, as well as a collection of magnificently despicable characters operating on both sides of the border. And it made me think: is it possible that the history of thirteenth-century Scotland is badly taught at the elementary and high-school levels? Because the version I learned implied that the clans should have seen that the needs of the nation took precedence over the interests of their own lineages.

But where in Europe was that the case, even in the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries? The Russian aristocratic clans fought, too, over precedence and privileges. The Russians did agree on the charismatic principle of the ruling dynasty, which existed apart and above the individual boyar clans. The turmoil in the early part of Ivan the Terrible’s (1530–84) reign—the subject of my Legends of the Five Directions novels—came about because the clans could not agree on the pecking order among themselves, since Ivan was too young to marry and establish said pecking order for them. But when the old dynasty died out in 1598 and a new one had to be chosen, Russia managed no better than Scotland. In both cases, the idea of “nation” meant little compared to the concept of lineage. Read in that light, Scottish history doesn’t seem so depressing after all.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Scotland, 1296: William Wallace is leading the resistance against the English while the clans fight one another as fiercely as they attack the invaders from the south. Two candidates in particular claim the throne: the Red Comyn and Bruce the Competitor. Neither can rule without support from Clan Macduff. But when Comyn secures the hand of Isabelle Macduff for his heir, his success appears assured. No matter that Isabelle prefers James Douglas, whose family supports Bruce. In 1296, a woman must accept her father’s choice of husband. Isabelle’s fate is sealed.

But Isabelle harbors an unfeminine ambition to see and touch the Stone of Scone, on which all of Scotland’s kings have been crowned. Even though the Stone lies in Westminster Abbey and Edward Longshanks controls half of Scotland, including the clan into which Isabelle has married against her will, she is determined to play a part in her country’s fractious politics. Her determination leads her along a long and tortuous path as the mercurial James, soon known as the Black Douglas, and the depressive Robert, grandson of Bruce the Competitor, struggle to overcome the divisions among the Scottish lords and rally support before the land of their birth falls completely under “proud Edward’s power.”

In The Spider and the Stone: A Novel of the Black Douglas (Brigid’s Fire Books, 2014), Glen Craney reveals the events that led up to and beyond the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. Rich in historical detail and powerful personalities in conflict, this is a story that picks up where Braveheart ends and follows the drive to keep Scotland independent to its successful, if temporary, conclusion.

Published on July 24, 2015 06:00

July 17, 2015

Keeping Watch

As will surprise approximately no one, this week saw the release of Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, referred to in the book description as “a landmark new novel set two decades after her beloved Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, To Kill a Mockingbird.” The book is hailed across the Internet as the long-awaited second book by a reclusive author and as the sequel to a classic.

As will surprise approximately no one, this week saw the release of Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman, referred to in the book description as “a landmark new novel set two decades after her beloved Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, To Kill a Mockingbird.” The book is hailed across the Internet as the long-awaited second book by a reclusive author and as the sequel to a classic.Now I have no objection to book publishers releasing highly anticipated books; publishing is a tough business, with few guaranteed successes and a lot of gambles. And if Harper Lee can make money in her old age off a book no one knew existed until a few years ago (stories vary on just how many), more power to her.

Still, it seems to me that we should be clear about what exactly this book is. It is not a second novel. It is not even a sequel, except in the sense that the action takes place twenty years after To Kill a Mockingbird. It is, as everyone involved freely admits, a rough draft that was not initially accepted for publication. That makes it very interesting, but for reasons other than those suggested by the phrases “sequel” and “second book.” And those who are complaining about the unexpected portrayals of Atticus Finch and of Scout might want to keep that distinction in mind.

One of the losses created by the widespread adoption of the computer—as marvelous and irreplaceable as that invention has been, for writers especially—is the virtual disappearance of rough drafts. Technologies change, hard disks fill up, projects end, and files are deleted or become unreadable. The many hand-copied drafts of War and Peace may have undermined the marriage of Leo and Sophia Tolstoy, but they are a treasure trove for literary scholars and historians. Watching a writer at work—pruning characters, developing motivations, changing plots and settings and even time periods, switching points of view—offers insights into the creative process and the craft of writing that can seldom be duplicated by other means.

Novels do not burst into life full grown, like Athena from the head of Zeus. They must be nurtured and cultivated, prodded and tested. What will heighten the conflict here? What adds to the drama there? Which perspective offers the most immediate impact or best serves the needs of the story? Does this character need more complexity or less? Should that person even play a part in the book? Does this one need an entire novel of her own? And so forth, and so on. Even in this era of instantaneous self-publication, most novels go through dozens of rewrites before the authors dare release their darlings into a cruel and unforgiving world.

So one day, when I can afford it, I will read both versions of Harper Lee’s classic novel to see what decisions she and her editor made that turned a rough draft—which the early reviews suggest was flawed, like any early draft—into that Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece. I will read them in order—Watchman, then Mockingbird—in a chapter by chapter comparison. I will watch the film with Gregory Peck, too, because turning a novel into a screenplay demands another level of skill. I will do these things because as a writer of historical and futuristic fiction, I want to master my craft and write the best novels I can. But I will not be expecting a sequel, and I will be surprised (perhaps even a bit disappointed) if Harper Lee’s “second” book turns out to be better than her first.

Image: Clipart no. 25851462.

Published on July 17, 2015 06:30

July 10, 2015

Fact Versus Fiction

Or How Accurate Can Historical Novels Be?

When I published The Golden Lynx and The Winged Horse, I told my fellow historians that these were novels accurate enough to assign to students. I don’t think I would say that today. Because my reasons get to the heart of a question that plagues many historical novelists, I’ve decided to share them here.

For sure, if you want to start a thriving discussion on GoodReads or Facebook, post a topic on the line separating fact from fiction in historical novels. A few years ago, the historian Ian Mortimer, who writes fiction under the pen name James Forrester, took issue with the prizewinning novelist Hilary Mantel over this very question—which Mortimer and I also discussed in our New Books in Historical Fiction interview. There are good arguments on both sides, but what is the essence of the debate?

In part, it’s a question of terminology. “Accurate,” to a historian, means verifiable from documentary or physical evidence. Details in a novel can often be verified, but the novel itself is an exercise of the imagination. As soon as an author creates a character and invests that character with thoughts and emotions and dialogue, the resulting product ceases to be verifiable and is therefore not accurate, in historical terms. Plausible maybe, well informed possibly, but not accurate. Moreover, historical novels, precisely because of their emotional power, can be insidious, in the sense that a reader caught up in a story—especially one that includes actual historical characters—may believe that something happened that the author has in fact made up or changed for the sake of the story. A historical note pointing out such differences helps, but memory has a way of retaining the scene and forgetting the caveat. Memory is linked to emotion, and fiction depends on feeling. Even without deliberate distortion (two characters rolled into one, for example), a novel creates images of a past that is to some extent not genuine.

Caption: Is This What a Real Boat Looked Like?

Caption: Is This What a Real Boat Looked Like?

Then there is the issue of errors and lacunae, in both the novels themselves and the history that informs them. I am a professional historian specializing in the area and the period in which I set my fiction, but I make mistakes too. It’s unavoidable. Sometimes the documents have vanished or never existed; sometimes the writer doesn’t find them in time; often interpretations differ—and even when they don’t, we seldom have a complete picture of the past. Historians can say “we don’t know”; novelists don’t have that luxury. To tell a coherent story, you must fill in the gaps.

Can we aim for authenticity, then? Admittedly, all writers, of both fiction and nonfiction, are creatures of the times in which we live. We see the past through a presentist lens. Perhaps more important, so do our readers. How many people want to read about a romantic hero who acts with the brutality of a twelfth-century knight, kills anyone who crosses him, thinks women have half a brain at best, and beats his wife and children? Yet a hero who is sensitive and enlightened enough for modern tastes can reasonably be judged inauthentic.

With certain exceptions, though, I would argue that authenticity and plausibility are attainable goals. The dictionary definitions of “authentic” include “worthy of acceptance or belief as conforming to or based on fact” and “conforming to an original so as to reproduce essential features.” To me, this exactly describes what good historical novelists do. A medieval knight carrying a cellphone or saying, “Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?” (unless it is a time-travel tale) is not authentic. A sixteenth-century Russian noble girl who expects to meet her future husband at the wedding is authentic (behaving in a manner true to her time); one who runs off with a boy she has met around the house or at church in defiance of her parents’ wishes had better have a darned good explanation and anticipate a difficult life. The unattainability of accuracy does not mean that anything goes.

Now, I have never pretended that my novels are anything other than fiction. And I stick as close to the facts as I can. Even today, I would argue that my Legends of the Five Directions series describes a world closer to contemporary historians’ perceptions of how sixteenth-century Russia operated than that presented in many older academic works. But the farther I get into this saga, the more I recognize the impossibility of verifying—or even researching—every detail that goes into my stories. And that is why these days I describe them as well informed or fun to read rather than as historically accurate portrayals of the Russian past.

Image: “Askold and Dir,” Radziwill Chronicle (late 15th century), via Wikimedia Commons. This image is in the public domain because of its age.

When I published The Golden Lynx and The Winged Horse, I told my fellow historians that these were novels accurate enough to assign to students. I don’t think I would say that today. Because my reasons get to the heart of a question that plagues many historical novelists, I’ve decided to share them here.

For sure, if you want to start a thriving discussion on GoodReads or Facebook, post a topic on the line separating fact from fiction in historical novels. A few years ago, the historian Ian Mortimer, who writes fiction under the pen name James Forrester, took issue with the prizewinning novelist Hilary Mantel over this very question—which Mortimer and I also discussed in our New Books in Historical Fiction interview. There are good arguments on both sides, but what is the essence of the debate?

In part, it’s a question of terminology. “Accurate,” to a historian, means verifiable from documentary or physical evidence. Details in a novel can often be verified, but the novel itself is an exercise of the imagination. As soon as an author creates a character and invests that character with thoughts and emotions and dialogue, the resulting product ceases to be verifiable and is therefore not accurate, in historical terms. Plausible maybe, well informed possibly, but not accurate. Moreover, historical novels, precisely because of their emotional power, can be insidious, in the sense that a reader caught up in a story—especially one that includes actual historical characters—may believe that something happened that the author has in fact made up or changed for the sake of the story. A historical note pointing out such differences helps, but memory has a way of retaining the scene and forgetting the caveat. Memory is linked to emotion, and fiction depends on feeling. Even without deliberate distortion (two characters rolled into one, for example), a novel creates images of a past that is to some extent not genuine.

Caption: Is This What a Real Boat Looked Like?

Caption: Is This What a Real Boat Looked Like?Then there is the issue of errors and lacunae, in both the novels themselves and the history that informs them. I am a professional historian specializing in the area and the period in which I set my fiction, but I make mistakes too. It’s unavoidable. Sometimes the documents have vanished or never existed; sometimes the writer doesn’t find them in time; often interpretations differ—and even when they don’t, we seldom have a complete picture of the past. Historians can say “we don’t know”; novelists don’t have that luxury. To tell a coherent story, you must fill in the gaps.

Can we aim for authenticity, then? Admittedly, all writers, of both fiction and nonfiction, are creatures of the times in which we live. We see the past through a presentist lens. Perhaps more important, so do our readers. How many people want to read about a romantic hero who acts with the brutality of a twelfth-century knight, kills anyone who crosses him, thinks women have half a brain at best, and beats his wife and children? Yet a hero who is sensitive and enlightened enough for modern tastes can reasonably be judged inauthentic.

With certain exceptions, though, I would argue that authenticity and plausibility are attainable goals. The dictionary definitions of “authentic” include “worthy of acceptance or belief as conforming to or based on fact” and “conforming to an original so as to reproduce essential features.” To me, this exactly describes what good historical novelists do. A medieval knight carrying a cellphone or saying, “Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?” (unless it is a time-travel tale) is not authentic. A sixteenth-century Russian noble girl who expects to meet her future husband at the wedding is authentic (behaving in a manner true to her time); one who runs off with a boy she has met around the house or at church in defiance of her parents’ wishes had better have a darned good explanation and anticipate a difficult life. The unattainability of accuracy does not mean that anything goes.

Now, I have never pretended that my novels are anything other than fiction. And I stick as close to the facts as I can. Even today, I would argue that my Legends of the Five Directions series describes a world closer to contemporary historians’ perceptions of how sixteenth-century Russia operated than that presented in many older academic works. But the farther I get into this saga, the more I recognize the impossibility of verifying—or even researching—every detail that goes into my stories. And that is why these days I describe them as well informed or fun to read rather than as historically accurate portrayals of the Russian past.

Image: “Askold and Dir,” Radziwill Chronicle (late 15th century), via Wikimedia Commons. This image is in the public domain because of its age.

Published on July 10, 2015 06:00

July 3, 2015

Independent’s Day

As I’ve made clear more than once, marketing is not my favorite part of life as a semi-independent author. Essential, yes. Enjoyable, not so much. But there is one big exception to my instinctive dislike for self-promotion, and that’s getting out and meeting readers and other writers. So when the local library approached me to show up at something they called the Independent’s Day Book Fair, I didn’t hesitate to say yes. I figured that even if no one showed up, I could hang around for a couple of hours chatting with other local authors, and that in itself would be worthwhile.

The first step, of course, was to ensure that I wasn’t the only member of Five Directions Press invited. I talked to my pals and the librarian in charge of organizing the event, and we agreed that we would all try to make it, sharing a single table to keep plenty of seats available for other folks. Between the initial contact and the event, Five Directions Press grew—and life intervened, as it tends to do—but in the end, five of us appeared yesterday with all eleven of our published books (a twelfth is due this fall), free bookmarks to give away, and our lovely Five Directions Press banner.

It was a lot of fun. We didn’t sell as many books as we hoped, but we made some great contacts and developed a healthy sense of how much excellent writing self-published authors are producing, from nonfiction to poetry. We got to hear a lot of interesting short talks from other writers and gave a short presentation of our own about Five Directions Press. So many thanks to the organizers, our fellow-participants, and the readers who chose to attend.

A happy Independence (Independent’s) Day to all!

The first step, of course, was to ensure that I wasn’t the only member of Five Directions Press invited. I talked to my pals and the librarian in charge of organizing the event, and we agreed that we would all try to make it, sharing a single table to keep plenty of seats available for other folks. Between the initial contact and the event, Five Directions Press grew—and life intervened, as it tends to do—but in the end, five of us appeared yesterday with all eleven of our published books (a twelfth is due this fall), free bookmarks to give away, and our lovely Five Directions Press banner.

It was a lot of fun. We didn’t sell as many books as we hoped, but we made some great contacts and developed a healthy sense of how much excellent writing self-published authors are producing, from nonfiction to poetry. We got to hear a lot of interesting short talks from other writers and gave a short presentation of our own about Five Directions Press. So many thanks to the organizers, our fellow-participants, and the readers who chose to attend.

A happy Independence (Independent’s) Day to all!

Published on July 03, 2015 09:28

June 26, 2015

Ways with Words

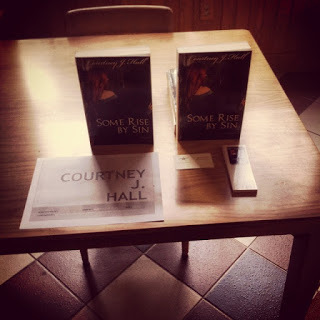

Languages fascinate me: the differences in their grammar, the way they change over time, the nuances and complexity of them. I speak and read three, know snippets of many more, and even write informally in a couple of them, but English—in all its glorious craziness—is, for better or worse, my first and foremost, my birthright. So when I stumbled across Bill Bryson’s The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got That Way on sale for Kindle at $1.99 (it still is, by the way, although I don’t know for how long), my perennial if ever-shaky resolution to keep my book budget under control took another hit.

Languages fascinate me: the differences in their grammar, the way they change over time, the nuances and complexity of them. I speak and read three, know snippets of many more, and even write informally in a couple of them, but English—in all its glorious craziness—is, for better or worse, my first and foremost, my birthright. So when I stumbled across Bill Bryson’s The Mother Tongue: English and How It Got That Way on sale for Kindle at $1.99 (it still is, by the way, although I don’t know for how long), my perennial if ever-shaky resolution to keep my book budget under control took another hit.Indeed, the book is a gem. More anecdotal than scholarly, full of the kind of declarations that make academics sharpen their pens to point out the many instances that don’t fit the generalizations, but for those very reasons a huge amount of fun. It’s true that I knew most of the big points already, but that didn’t interfere with my enjoyment one bit.

Some snippets of information were truer than I might have imagined: that English has a huge vocabulary I knew; that the revised Oxford English Dictionary lists 615,000 words, which don’t include many technical and scientific terms, was a higher total than I would have guessed. Other arguments I disagree with: English grammar is complex and its spelling simple? Tell that to the student facing an exam in Russian. When I began taking Russian in high school, people assumed the alphabet would be difficult to learn. But the alphabet is a snap: many of the letters look like Latin or Greek; the handful that don’t are easily memorized; and the whole thing is phonetic, with a few minor and regular variations. Figuring out where the accent falls is a bit of a challenge, since English speakers rarely get it right: it’s Ba-REES, not BO-ris; Vlad-EE-mir, not VLAD-imir; Ee-VAN, not EYE-van, and so on. But the sounds are right there in front of you, ready to speak.

The grammar, though, makes English look like a walk in the park (this may be in part because as a native, I have trouble explaining the difference between a pluperfect and a subjunctive, but I instinctively know when to use articles and the difference between “I went” and “I was going”). Three genders, assigned more or less arbitrarily; six cases, which have clear uses but many not so clear; two forms for every verb, including sixteen verbs of motion, used in ways that at times seem to be quite opposite to their English counterparts; and, in addition to singular and plural, relics of the old dual number, now sometimes confusingly extended to three and four, where it appears to be either an irregular plural or genitive singular, although it is nothing of the kind—next to all that, the difference between “I go to the bank on Tuesdays” and “I am going to the bank right now” pales by comparison.

English spelling and pronunciation, in contrast, routinely trip up people who have gone through the entire public school system, college, and even graduate school. They trip up editors, as I discovered when I took Bryson’s “test.” They trip up computers, which can’t tell the difference between their, there, and they’re, never mind which belongs where in “They’re going to take their car there.” Certainly, Welsh and Irish (any of their Celtic cousins, in fact) look more confusing still, but that doesn’t make English spelling or pronunciation easy to master.

But enough quibbles. Whether you agree with every sentence or not, Bryson’s book is a wonderfully written exploration of our free-wheeling mother tongue—its origins, its development, its place in the modern world (and the forms it is evolving into), and its tendency, as the cliché goes, to lurk in dark alleys, where it assaults other languages and rifles their pockets for loose words.

On another note, most of the Five Directions Press authors are taking part in an Independents’ Day Book Fair on July 2, 2015. More on that next week. Meanwhile, you can find the full information at our website. We’ll be selling books at a discount and will autograph them on the spot if you request. We will also have free bookmarks as mementos. If you’re in the area, stop by and say hello!

Published on June 26, 2015 13:42

June 19, 2015

The Romance of the Spy

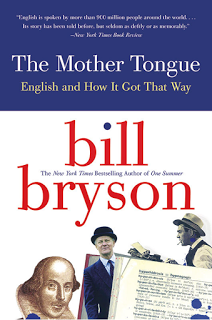

I have to admit: I’m a sucker for a good adventure romance, especially if it has history thrown in. Some near-universal favorites don’t sweep me up—for example, I loved the film of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy but have never managed to get into the book, despite repeated attempts. It has to be me, not LeCarré, but that changes nothing. Give me The Scarlet Pimpernel, though—Baroness Orczy’s purple prose and love for “tell, don’t show” notwithstanding—and I gobble it down like artisanal chocolate, no matter how many times I have read it before.

I have to admit: I’m a sucker for a good adventure romance, especially if it has history thrown in. Some near-universal favorites don’t sweep me up—for example, I loved the film of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy but have never managed to get into the book, despite repeated attempts. It has to be me, not LeCarré, but that changes nothing. Give me The Scarlet Pimpernel, though—Baroness Orczy’s purple prose and love for “tell, don’t show” notwithstanding—and I gobble it down like artisanal chocolate, no matter how many times I have read it before.So you can imagine my delight when, during a magical media lunch in New York a month ago, I learned from Lisa Chaplin, author of The Tide Watchers, that there really was a British spy in the era of the French Revolution who went by the code name the Scarlet Pimpernel. Where Orczy learned of him (if she did), I have no idea. It seems too big a coincidence that she made the name up—let’s face it, can you imagine a goofier code name for a secret agent?—if a real person with that moniker existed. But I had never heard before that the ineffable Sir Percy might have a real-life counterpart. And if he did, that counterpart almost certainly belonged to the nobility, since most of the high-level espionage agents at the time came from that class.

Lisa and I don’t talk about the Scarlet Pimpernel specifically in this month’s interview for New Books in Historical Fiction. But we do talk about female spies, a real-life would-be assassin popularly known as the Mad Baron, Robert Fulton’s bizarre love life, the fun of research (and speculation), and the path from contemporary romance to contemporary espionage to the romance of the spy in Napoleonic Europe. So listen in; I’m sure you won’t be disappointed.

Here’s a teaser, as usual taken from the post I wrote for New Books in Historical Fiction:

From World War I, we jump back more than a hundred years and across an ocean. Napoleon, still First Consul, has convinced the surrounding nations to accept a series of treaties that he violates as it suits him. Great Britain, weary of war, clings to the Treaty of Amiens, determined to play the ostrich even as evidence mounts that Napoleon is massing an invasion fleet on the northern coast of France. What are the alternatives? In 1802, the Battle of Trafalgar has not yet happened. Half the renowned British fleet is in mothballs, the other half dispersed to distant lands. And no one knows (or wants to know) where Bonaparte will strike next: Egypt, the Caribbean, the Channel Islands, Cornwall. Any target is as plausible as any other, or so the Parliament and the lords of Whitehall insist.

Amid the confusion, a small group of British spies, the King’s Men, works to gain what intelligence it can on Bonaparte’s movements. Talk of assassination plots mingle with rumors of troop deployments and underwater boats capable of launching carcasses (bombs) and torpedoes to destroy the Royal Navy before its officers know what has happened to them. And smack in the middle of the plot is Elizabeth Sunderland, daughter of a King’s Man, who realizes too late the wolf hidden behind the charming face that wooed her away from her family. Lisbeth wants her son, her estranged husband wants revenge, the King’s Men want information, and the American inventor Robert Fulton wants only to be left in peace to pursue his research into submarines. In The Tide Watchers (William Morrow, 2015), Lisa Chaplin masterfully weaves these warring desires into a fast-paced story that will keep you riveted in your seat as the pages turn.

Published on June 19, 2015 06:30

June 12, 2015

Preliminary Results

This time last week, I was running a free promotion on my science fiction romance series, Desert Flower and Kingdom of the Shades, as reported in “Ballet Shoes (on Sale).”

This time last week, I was running a free promotion on my science fiction romance series, Desert Flower and Kingdom of the Shades, as reported in “Ballet Shoes (on Sale).”As noted in various places, this was my first-ever free promotion. I ran a countdown deal in December 2014, also on these two books (the only ones enrolled in KDP Select, the exclusive-to-Amazon distribution program), with dismal results. And back in 2012, I ran a straight half-price reduction sale on my then two books, The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel and The Golden Lynx, with a slightly better outcome. But I had never tried free, in part because the deluge of free content available on the Internet worries me. Art of all sorts takes time and effort and training to produce, then edit into something worthwhile. Creators deserve recompense for that investment of passion and attention.

Still, I was curious what would happen, and a week later I can report three findings.

1. People still download free books. This point seems obvious, but I wasn’t sure it would pan out. First, modern users are saturated with free content. Second, these books have been free to Kindle users for a while, through the Prime and Unlimited subscriptions; they do get borrowed, but not so often that I felt certain that people would download them. But they did: 71 copies of Desert Flower and 67 of Kingdom of the Shades during the 48 hours of the sale. How many people will read the books, never mind pay for other books that are not free, remains unknown. Still, almost 70 people now have access to my books who did not before. That is good news. You could argue that I lost about $400 in royalties, but I suspect that’s not so. Most likely, these readers would not have paid the $3.99 that the books cost when not on sale, so in that sense I lost nothing that I ever really had. It was an experiment, so I’m fine with that.

2. Facebook ads work. Although Bookbub is the current go-to source for advertising e-book promotions, I decided not to apply there. Listings are expensive, starting at $150 for a free book, depending on the category. Instead, I paid Facebook $35 over two days to boost my post. At the end of the second day, almost 4,300 people had seen the ad, and 2% clicked through to find out more. That may not sound like much, but for advertising, it’s a typical response rate.

The one thing I would change (if I can figure out how it’s calculated) is my relevance score. At 4/10, each click cost me 76¢. When we boosted the announcement for Some Rise by Sin, the results were similar, but the clicks cost 22¢ apiece, because the Facebook computers considered the targeting “more relevant.” But what made those categories more relevant I have yet to discover.

3. It doesn’t take much to raise Amazon bestseller rankings significantly. At the height of the promotion near the end of the first day, with 55 downloads of Desert Flower and 53 of Kingdom of the Shades, the two books had risen from ranges of 12,400 and 18,600, respectively, to about 3,500 among all free books. Desert Flower hit no. 43 in Kindle eBooks > Romance > Science Fiction; Kingdom peaked at no. 49 on the same list. If I had managed to give away twice as many copies in the same time frame, I probably could have cracked the top ten, albeit in this relatively unpopulated list. Although I don’t control how many people download my books, it’s useful to have a better sense of what those rankings mean. A good advertising plan could raise the profile of my books significantly—at least until the algorithms change.

Any benefit is, however, brief. By the morning after the promotion ended, the sales ranks had plunged again, because the books were now competing with the much larger number of paid titles: both novels dropped below 1,000,000, although they remained much higher than they had been before the promotion began. Since then, I have sold no books at all, either print or Kindle. Even borrowings have flattened out.

Will I try it again? “Never say never,” as the adage goes. I would need a good reason to go against the grain a second time, and so far the results seem rather mixed. But then, that’s the point of an experiment.

Image: Clipart.com no. 20574032.

Published on June 12, 2015 06:30

June 4, 2015

Ballet Shoes (on Sale)

When I was seven, my parents took me to see The Snow Maiden, as performed by the London Festival Ballet, now the English National Ballet. I fell in love with ballet, then and forever. In the years since, I have seen many great dancers: Maya Plisetkaya, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Altynai Assylmuratova, Julio Bocca, Nina Ananiashvili, Ethan Stiefel, Gillian Murphy, Peter Boals. And those are just a few of the live performances; on television and video I have watched an uncounted number of Giselles, Kitris, Juliets, Nikiyas, Medoras, and more. I took class as a child, then for twenty-five years as an adult of dubious competence but sincere dedication; I still dance in my office most days to offset the unhealthful effects of too many hours sitting at my computer. I love Balanchine and Ratmansky and Wheeldon, too, but when push comes to shove, it’s the old story ballets that tug at my heart strings. A couple of decades ago, I created my own ballerina, Alessandra Sinclair—informally known as Sasha—just to explore what meaning those old nineteenth-century classics might have for our modern world. And now I offer her two books, free of charge, for forty-eight hours—to celebrate the seventh anniversary this month of my invaluable writers’ group, the basis of Five Directions Press.

When I was seven, my parents took me to see The Snow Maiden, as performed by the London Festival Ballet, now the English National Ballet. I fell in love with ballet, then and forever. In the years since, I have seen many great dancers: Maya Plisetkaya, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Altynai Assylmuratova, Julio Bocca, Nina Ananiashvili, Ethan Stiefel, Gillian Murphy, Peter Boals. And those are just a few of the live performances; on television and video I have watched an uncounted number of Giselles, Kitris, Juliets, Nikiyas, Medoras, and more. I took class as a child, then for twenty-five years as an adult of dubious competence but sincere dedication; I still dance in my office most days to offset the unhealthful effects of too many hours sitting at my computer. I love Balanchine and Ratmansky and Wheeldon, too, but when push comes to shove, it’s the old story ballets that tug at my heart strings. A couple of decades ago, I created my own ballerina, Alessandra Sinclair—informally known as Sasha—just to explore what meaning those old nineteenth-century classics might have for our modern world. And now I offer her two books, free of charge, for forty-eight hours—to celebrate the seventh anniversary this month of my invaluable writers’ group, the basis of Five Directions Press.Desert Flower (based on Giselle) and Kingdom of the Shades (La Bayadère) will be available without charge for Kindle apps and devices from 12:01 AM on Friday, June 5, to 11:59 PM on Saturday, June 6 (Pacific Daylight Time). If you love ballet and romance (the science aspect is minimal) or just want to see whether you like my style enough to take a chance on my historical fiction, here’s your opportunity. Don’t miss it: this is my first free promotion in three years, and it may well be the last....

Descriptions, excerpts, and links follow.

Desert Flower

Love plays no part in marriage arrangements on the desert planet of Tarkei. So when Danion, junior priest of the sun goddess, finds himself drawn, in defiance of his oath of celibacy, to a human ballerina encountered by chance, he does his best to resist. The ballerina, tormented by memories of violence that may be real or just the product of an unknown enemy's twisted mind, has no interest in him anyway—or so they think.

But Tarkei has an ancient tradition: that two unusually compatible people, whether they believe they belong together or not, can bond at first touch. Once formed, the link lasts until death. Legend calls it “the joining.” Danion calls it a myth. He and his ballerina will soon discover who’s right.

Excerpt

Fabric gleamed in the flickering candle flame. Shadows danced on the cave walls. Blush pink ribbons slid through her fingers—soft and smooth. Once, before her mother died, she had stroked a m’retta with fur like this.

“What are these?” Entranced, Choli held out her find to the man who sat cross-legged in the corner, who had watched without speaking while she rummaged through his few possessions. Tall and slender, dark-haired, dark-eyed, olive-skinned, austere in his charcoal robe, he looked like the men of her world. But no man of her world would have tolerated her presence, never mind giving her free run of his home. This one sat, still as the rocks at his back, hands folded like a scholar or a priest. Or so they said, the people of the caves.

Choli wondered how they knew. Scholars were rare among the Kazrati. In her thirteen years, she had not met a single one. Priests were not so rare, but they were intimidating. Danion, of course, was not Kazrati, although he appeared to be.

His deep, cool voice answered the question she had almost forgotten asking. “They are shoes.”

Kingdom of the Shades

Sixty-three years have passed since the meeting of Danion and his ballerina in the desert, but the memory of her continues to haunt him. Until one day in a cafeteria barely worth the name, an exchange with a surly waitress ends with him staring at that beloved form. A holographic projection—or Sasha herself, inexplicably restored to life?

Tarkei do not believe in miracles, but the evidence points to Sasha’s return. At last, Danion and his wife can be together. Or could, if he had not taken responsibility for guiding a group of young rebels whom he cannot abandon—not once he recognizes the existence of a traitor in their midst.

Excerpt

Spirit voices surrounded her, speaking a language she did not understand but vaguely recognized as one she had heard before. White light hurt her eyes, brilliant light that shone through her closed lids, causing pain even though she could not open them. If she had the strength to move, she would have turned her head. Instead, she seemed to be floating in a sea of light, the spirit voices bearing her up.

Slowly, the images crystallized. She could not see, but she could hear. The words took shape in her head. She struggled to separate them, to wrest the meaning from them, but at the instant they became clear, sensation left her, and she sank back into darkness.

And so it went, for how long she did not know. Wherever she was, time did not exist. She floated from the tunnel of darkness to the sea of light and back, spirit voices rising and falling around her.

Sasha Sinclair lay between soft clean sheets, listening to words that she almost understood. Her head ached; her whole body ached, as if someone had taken a bat and broken every bone she had. Her skin felt scorched; the sheets weighed her down, sticking to the curled paper that had once been epidermis.

Image no. 20528287, purchased from Clipart.com.

Published on June 04, 2015 21:15