C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 49

January 9, 2015

The Empty Throne

As Bernard Cornwell’s millions of fans can testify, HarperCollins released the latest of his Saxon Tales (no. 8) in the United States three days ago. Of course, readers in the UK and Australia have had The Empty Throne for months, which is nice for them. But for us here in the USA, it’s been available only as advance review copies (ARCs) until now.

As Bernard Cornwell’s millions of fans can testify, HarperCollins released the latest of his Saxon Tales (no. 8) in the United States three days ago. Of course, readers in the UK and Australia have had The Empty Throne for months, which is nice for them. But for us here in the USA, it’s been available only as advance review copies (ARCs) until now.One perk (actually, the main perk besides having the chance to chat with a bunch of fascinating and informative people) of hosting New Books in Historical Fiction is that publishers send me books for free, either because I ask for them or because the publicists hope I will like the novels enough to request an interview. One book I received unsolicited was Bernard Cornwell’s The Pagan Lord, the previous Saxon Tale. It had to arrive unsolicited because, although I knew who Bernard Cornwell was, I’d always rather assumed that his books were more Sir Percy’s cup of tea than mine. I’ve read a lot of books set in wartime, of course, but generally not books told from the point of view of a warrior. But since my Daniil and Ogodai are warriors—as almost all male aristocrats at the time were—I thought it would be good for my writing as well as a wonderful coup for New Books in Historical Fiction to read this book and interview Bernard.

As it turned out, I loved the book. I read several others earlier in the series and plan to read more. And I very much enjoyed my conversation with Bernard. Skype was not on its best behavior that day—in fact, it’s never behaved worse—but Marshall Poe, editor in chief of the New Books Network, did a great job of fixing the flaws. For more about the interview, see “There’s Always Been an England?” Or just listen to and download the free podcast by clicking on the link earlier in this paragraph.

As a result, I was delighted to receive a copy of The Empty Throne. Bernard’s publicist and I decided that it would be more effective to wait for a few more books in the series to come out before we schedule another interview, so instead I have reviewed the book on Amazon.com (as CJP), BookLikes, and Goodreads and linked to the review on Facebook, as well as other social media. I won’t repeat that review verbatim here. Instead, I’d like to focus on one element of the story that I find particularly effective. That is Cornwell’s handling of his hero’s advancing age.

Elizabeth Peters, the mystery writer whose death I memorialized in “The Sands of Time,” once said that if she’d known how popular her heroine Amelia Peabody would become, she would never have mentioned her age in the first book (I’m paraphrasing—these are not her exact words). Amelia was thirty-two when she met her husband Emerson, who was a few years older than she, in 1884; and by the time Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun almost four decades later, readers did have to suspend disbelief to follow Peabody and Emerson through their escapades on the Western Bank. I structured my Legends series as I did in part to avoid that problem (not that I have anything like Elizabeth Peters’ readership, but one can hope); even if it does continue, as I’m beginning to think it may, past the original five books into a short spinoff series, it still won’t extend over more than ten years in time.

But Cornwell’s series is different, in that I suspect the author knew from the beginning that he would follow his hero Uhtred into extreme old age. Cornwell’s larger story traces the formation of a united England out of seven warring kingdoms, and however fictional Uhtred’s life, it follows a historical timeline that was set a millennium ago. When Cornwell decided to start The Last Kingdom (Saxon Tale no. 1, due to become a blockbuster BBC miniseries someday soon) with Uhtred as a ten-year-old in 866, he could predict that his saga must cover seventy years or so. Even Uhtred, the mightiest of mighty warlords, may have a hard time swinging his sword Serpent Breath at eighty.

The Empty Throne is where we begin to see how Cornwell plans to handle that problem going forward. The book opens with wording almost identical to that of The Last Kingdom: “My name is Uhtred. I am the son of Uhtred, who was the son of Uhtred, and his father was also called Uhtred. My father wrote his name thus, Uhtred, but I have seen the name written as Utred, Ughtred, or even Ootred.” And with that third sentence, an alert reader understands that this speaker is not the Uhtred of The Last Kingdom, whose father could not read or write, but another with the same name. The whole first chapter is told in the past tense, as if the speaker’s father were dead, and reveals this new Uhtred to be a true chip off the old block, to borrow a cliché.

It’s a clever device, and it works. The son can swashbuckle to his heart’s content, while his father, true to his character, ignores a serious wound in his struggle to protect and promote the Saxon cause. And as readers, we have to wonder whether at some point Cornwell will pull the rug out from under us and retire the older Uhtred altogether, leaving his son to supervise the final unification of England. In this sense, the title is a double play on words: the empty throne is not only Alfred’s but also potentially Uhtred’s. The introduction of a new narrator creates uncertainty, uncertainty creates tension, and tension pulls readers into the story. What else, in the end, does a novelist want?

I hope Uhtred the Elder makes it to the end. Like so many others, I have become rather attached to him. But I tip my imaginary helmet to Cornwell, who has been and remains a master storyteller. And you can bet I’ll be standing in line for book 9.

Published on January 09, 2015 06:00

January 2, 2015

The Checklist, Round 3

So, as I wrote last week, I met and at times exceeded my goals for last year, some of which I had rolled over from 2013. What’s next?

So, as I wrote last week, I met and at times exceeded my goals for last year, some of which I had rolled over from 2013. What’s next?Obviously, I want to continue to post weekly on this blog and conduct monthly interviews for New Books in Historical Fiction. Last year, we galloped across much of the globe: Afghanistan, England from the Saxons to Austen, Italy, Russia, the Wild West, ancient Egypt, Spain—even the far reaches of the eighth-century Silk Road. This year starts out with Germany and Gutenberg, then zips off to medieval Scotland, first-century Israel, Colonial America, an alternative medieval universe, and beyond. I already have more books than slots, which is a wonderful place to be.

Although last year’s challenges were fun, I don’t think I’ll sign up for any this year. Between the NBHF books and group reads on Goodreads and research, I have a full plate as it is. Pile on to that, and reading starts to feel like a chore, instead of the escape it has been since the day I learned to recognize the letter A. And having published five books in the last three years, I probably will not have a new one in 2015, unless The Swan Princess goes so much faster than expected that I can bring it out in December. Five Directions Press is set to expand, though. Production will soon begin on Courtney J. Hall’s Some Rise by Sin, which should be ready by the end of January. With luck, we will add a couple more titles, and perhaps a new author, in 2015.

My main goal is to write—part of which involves clearing more time for writing than my current schedule allows. Otherwise, I waste half my weekend getting back up to speed, only to crash into a ditch when Monday arrives. Two hours a day would be ideal, with more on weekends. Three days a week would be a good alternative. We’ll have to see what the market provides. Last year it took away income without freeing up time. Let’s hope that 2015 proves better in that regard.

So, not necessarily in order of importance, and not including the truly vital parts of life such as family and friends, my goals for next year are to:

find more time to write, without having unpaid bills;

use that time to finish at least the rough draft of The Swan Princess;

copy edit and typeset books and maintain the website for Five Directions Press;

read twelve books and interview their authors for New Books in Historical Fiction;

maintain this blog on a regular weekly schedule; and

learn more about marketing—the weak link in most authors’ education, and certainly mine.

Shouldn’t be too hard, right? After all, I would do most of these things anyway. Except for the marketing, I even enjoy them. So let’s see how it goes. As usual, I’ll be back at the end of the year to report how I did.

And in the meantime, Happy New Year. May 2015 bring peace and prosperity to you all!

Image created by me in Adobe InDesign, using clip art from MS Word.

Published on January 02, 2015 06:00

December 26, 2014

The Year in Review

Time for the annual roundup, as I write the last post of the year. Hard to believe 2014 has already gone from Christmas Future to Christmas Past (and I hope yours was lovely). So, what do I have to show for another year on the planet?

Quite a bit, as it turns out. I completed my two challenges for the year, reading fifteen pure history books (actually more, but I stopped counting at fifteen) for the Sail to the Past History Challenge and twenty-six books from my To Be Read pile to sit atop the summit of Mont Blanc for the Reduce the TBR Mountain Challenge. Of course, I added two books to the TBR pile for every one I took off, but that’s what it means to be a bookworm. And doubling the number of books required for the status of historian in the History Challenge seems just about right for an actual historian. Most of my colleagues were rolling on the floor at the thought that anyone would read a mere seven full-length historical studies in a year.

In addition, of course, I conducted thirteen interviews for New Books in Historical Fiction, for which I read at least sixteen books. I published three of my own: The Winged Horse in June as planned, followed by a spur-of-the-moment decision to revise and release Desert Flower and Kingdom of the Shades to test the new Kindle Unlimited (KU) program introduced by Amazon.com in July. The last two books came out on August 29, just before Labor Day, and did very well their first month—while many people were using their 30-day free KU trial, I suspect. Since then, they have languished. Even my recent attempt to run a Kindle Countdown Deal on them was a flop, although this result seems to have more to do with the effects of KU than with me personally. Many authors are complaining of dramatic declines in their earnings from books enrolled in KU since October; for one example, see this post by M. Louisa Locke. In a similar vein, Countdown Deals unaccompanied by pricy ads apparently don’t do well.

Nonetheless, Desert Flower has garnered some good reviews, the whole thing was an experiment, three giveaways of The Winged Horse went much better, and my novels as a group sell slowly but steadily, so I have no inclination to complain. For the moment, I intend to wait and see what the next year brings. Meanwhile, Five Directions Press is growing: it now has eight books by four authors, with Courtney J. Hall’s Some Rise by Sin complete and ready for production in January. We hope to expand further in 2015.

With Winged Horse in flight, I turned to Legends 3, The Swan Princess. It took a surprisingly long time to get going, in part because I needed to research medieval medicine and certain specific medical conditions that play a part in the story, but more because I needed to figure out what the emotional story was. I knew which characters I wanted to feature from previous books, and I had an idea of what they should do, but I had a much harder time figuring out how they had grown since I last spent time with them and therefore what they next needed to learn. As a result, I spent months tweaking an outline that, as usual, I abandoned (except for the general direction) within twenty pages. But thanks to my inestimable critique group, I’ve more or less figured it out now, and with two lovely weeks of writing vacation to work with, I’m hoping to turn my initial four chapters into twice that by the first Sunday of the new year—at which time work returns with a bang.

Last but not least, I have written fifty-five blog posts since this time last year, including this one and several guest posts on other sites. I won’t say that has been my greatest triumph, because the interviews are fun and having five novels published and a sixth underway makes me feel pretty chuffed. But I do love these weekly posts, and I hope to keep them up throughout 2015. (For more goals, check back next week.)

Wherever you are, thank you for reading my ramblings for another year. May your holidays be merry and bright. And now, where’s that egg nog?

Image © 2009 Michael Wade, via Wikimedia Commons.

Creative Commons Attribute 2.0 Generic license.

Quite a bit, as it turns out. I completed my two challenges for the year, reading fifteen pure history books (actually more, but I stopped counting at fifteen) for the Sail to the Past History Challenge and twenty-six books from my To Be Read pile to sit atop the summit of Mont Blanc for the Reduce the TBR Mountain Challenge. Of course, I added two books to the TBR pile for every one I took off, but that’s what it means to be a bookworm. And doubling the number of books required for the status of historian in the History Challenge seems just about right for an actual historian. Most of my colleagues were rolling on the floor at the thought that anyone would read a mere seven full-length historical studies in a year.

In addition, of course, I conducted thirteen interviews for New Books in Historical Fiction, for which I read at least sixteen books. I published three of my own: The Winged Horse in June as planned, followed by a spur-of-the-moment decision to revise and release Desert Flower and Kingdom of the Shades to test the new Kindle Unlimited (KU) program introduced by Amazon.com in July. The last two books came out on August 29, just before Labor Day, and did very well their first month—while many people were using their 30-day free KU trial, I suspect. Since then, they have languished. Even my recent attempt to run a Kindle Countdown Deal on them was a flop, although this result seems to have more to do with the effects of KU than with me personally. Many authors are complaining of dramatic declines in their earnings from books enrolled in KU since October; for one example, see this post by M. Louisa Locke. In a similar vein, Countdown Deals unaccompanied by pricy ads apparently don’t do well.

Nonetheless, Desert Flower has garnered some good reviews, the whole thing was an experiment, three giveaways of The Winged Horse went much better, and my novels as a group sell slowly but steadily, so I have no inclination to complain. For the moment, I intend to wait and see what the next year brings. Meanwhile, Five Directions Press is growing: it now has eight books by four authors, with Courtney J. Hall’s Some Rise by Sin complete and ready for production in January. We hope to expand further in 2015.

With Winged Horse in flight, I turned to Legends 3, The Swan Princess. It took a surprisingly long time to get going, in part because I needed to research medieval medicine and certain specific medical conditions that play a part in the story, but more because I needed to figure out what the emotional story was. I knew which characters I wanted to feature from previous books, and I had an idea of what they should do, but I had a much harder time figuring out how they had grown since I last spent time with them and therefore what they next needed to learn. As a result, I spent months tweaking an outline that, as usual, I abandoned (except for the general direction) within twenty pages. But thanks to my inestimable critique group, I’ve more or less figured it out now, and with two lovely weeks of writing vacation to work with, I’m hoping to turn my initial four chapters into twice that by the first Sunday of the new year—at which time work returns with a bang.

Last but not least, I have written fifty-five blog posts since this time last year, including this one and several guest posts on other sites. I won’t say that has been my greatest triumph, because the interviews are fun and having five novels published and a sixth underway makes me feel pretty chuffed. But I do love these weekly posts, and I hope to keep them up throughout 2015. (For more goals, check back next week.)

Wherever you are, thank you for reading my ramblings for another year. May your holidays be merry and bright. And now, where’s that egg nog?

Image © 2009 Michael Wade, via Wikimedia Commons.

Creative Commons Attribute 2.0 Generic license.

Published on December 26, 2014 06:00

December 19, 2014

The Art of Life

One of the difficult steps in my expansion from writing history to producing historical fiction was mastering the art of the historical detail. Not in the sense that historical novelists often get themselves into trouble: by insisting on cramming every factoid they have carefully researched into their books regardless of whether it fits the story or turns it into the fictional equivalent of a Strasbourg goose. As a scholar of an unfamiliar time and place who stumbled into a fantastically specialized area of study while writing her dissertation, I long ago mastered what Sir Percy calls the “cocktail party spiel”—the ability to summarize a complicated project in twenty-five words or less. The alternative was to watch people’s eyes glaze over as they edged for the bar (literal or figurative—and if you’ve ever wondered why I write novels under a pen name, it’s to protect innocent readers from my academic work). So as a novelist and as a historian, I am a big fan of “look it up,” as in if readers want to know more, that’s what they’ll do.

One of the difficult steps in my expansion from writing history to producing historical fiction was mastering the art of the historical detail. Not in the sense that historical novelists often get themselves into trouble: by insisting on cramming every factoid they have carefully researched into their books regardless of whether it fits the story or turns it into the fictional equivalent of a Strasbourg goose. As a scholar of an unfamiliar time and place who stumbled into a fantastically specialized area of study while writing her dissertation, I long ago mastered what Sir Percy calls the “cocktail party spiel”—the ability to summarize a complicated project in twenty-five words or less. The alternative was to watch people’s eyes glaze over as they edged for the bar (literal or figurative—and if you’ve ever wondered why I write novels under a pen name, it’s to protect innocent readers from my academic work). So as a novelist and as a historian, I am a big fan of “look it up,” as in if readers want to know more, that’s what they’ll do.No, the difficulty I had was in mastering the concept of the emotional detail. Historians look for facts, to the extent that we can extract them from often-biased documents, and the facts of a historical event often fail to convey how that event affected the people caught up in it. The lower a person’s social standing, the less likely we are to find written documentation that reveals that person’s inner life. Or, as Laura Morelli puts it in her interview with New Books in Historical Fiction, we know about the lower classes (in her case, the boatmen of sixteenth-century Venice) mostly when they get themselves into trouble with the law.

Of course, roustabouts and troublemakers are more fun to write and read about than prissy heroines and noble youth who never harbor an unkind thought. But our necessary reliance on the skewed record left to us by history requires us novelists to use our imaginations creatively to develop, within the framework of what we can know about the general attitudes and life situations of specific groups in specific times and places, a creative understanding that we can apply to the circumstances of individual characters—themselves our inventions.

The results, when we get it right, sweep the reader into the past as no dry-as-dust treatise ever can. Take, for example, these two paragraphs from The Gondola Maker.

Peering further back into the shadows, I observe what appears to be years’ worth of neglected belongings: furniture covered in drapes, shelves stacked high with discarded tools, household goods, and more. Within this jumble, my eyes begin to make out the shape of another gondola stored in dry dock, turned upside down on a pair of trestles. The boat is partially covered with a large swath of canvas, but from the portion of the craft that is visible, I see that it is very old and neglected. The paint is dull and scratched, and part of the wood is split on one side, probably the result of some long-ago crash.

My heart leaps as I notice the carved maple leaf emblem on the prow of the boat. Even through the darkness, I would recognize it anywhere: the old gondola was made in my father’s boatyard. (107)

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction. If you listen to the interview, the NPR story I mention is also available online and free of charge.

As the son and heir to the workshop of sixteenth-century Venice’s premier gondola maker, Luca Vianello has his career, his marriage, and his place in society mapped out for him. True, his stern father still grieves for Luca’s older brother who died in childhood. And Luca’s left-handedness—viewed in Renaissance Europe as sinister, even demonic—provokes blows from his father even as it causes him to lag behind his younger brother in developing his skills. But it is only when tragedy shoots Luca out of his family’s boat-building business altogether that he can envision the possibility of change.

Through luck, Luca lands a position in another Venetian boatyard, far less prosperous than the workshop to which he was born. He loads boxes, succeeds as an errand boy, and befriends an older, more experienced gondolier determined to introduce Luca to the charms of wine, women, and on-the-side deals. Before long, Luca has become the private boatman of Master Trevisan, painter to Venice’s elite. There Luca encounters both the beautiful Giuliana Zanchi (and Trevisan’s portrait of her) and the abandoned, broken-down gondola that will become his personal restoration project.

Laura Morelli is an art historian and the author of, among other nonfiction works, Made in Italy and Artisans of Venice. In her award-winning debut novel, The Gondola Maker, she draws on her extensive knowledge of the Venetian past and present to recreate a lost fictional world that will astonish you with its rich, varied, endlessly fascinating detail.

Published on December 19, 2014 06:00

December 12, 2014

Red Fish, Blue Fish

I was answering questions last week about Five Directions Press, the author collective my writers’ group founded in the summer of 2012. The questions are for an article that fellow-novelist Deb Vanasse has agreed to write for the monthly magazine IBPA Independent, so we are flattered just to be included. Once I know when the Independent Book Publishers Association plans to run Deb’s article, I will post the information here. But the questions got me thinking about the place that author collectives occupy within publishing as a whole.

I was answering questions last week about Five Directions Press, the author collective my writers’ group founded in the summer of 2012. The questions are for an article that fellow-novelist Deb Vanasse has agreed to write for the monthly magazine IBPA Independent, so we are flattered just to be included. Once I know when the Independent Book Publishers Association plans to run Deb’s article, I will post the information here. But the questions got me thinking about the place that author collectives occupy within publishing as a whole. The question that struck me involved the relative advantages and disadvantages of traditional publishing and author collectives. The question rests on an implicit dichotomy that crops up a lot in discussions of the new publishing climate. Traditional or self-publishing: Which is better? Which will triumph? Which best serves authors? A lot of energy goes into defending one’s own choice and running down the other side.

But why? Surely publishing is big enough to include self-published authors, author collectives, small presses, and large corporate publishing houses. Trade publishing houses and author collectives serve different markets and as a result operate differently. They don’t compete; they complement one another.

The Big Five are huge corporate enterprises. Their employees have extensive experience producing and marketing books. Once they sign an author, they can offer a level of support that self-published authors, even if they set up a collective, can’t hope to match. A trade publisher works with the author to develop a manuscript, provides copy editing and cover design, turns the edited text over to its production department to design and compose the printed book and produce the e-book version, then sends the finished book to a publicist who will organize the marketing campaign.

Furthermore, a trade publisher has connections and prestige that get its books reviewed by major publications and into bookstores; radio and television broadcasters compete to interview its authors. Its titles have a far better chance of being noticed than those of writers who publish on their own or through a small press or an author collective, whose works can easily sink beneath the waves generated by the thousands of books released online every day. Self-published authors can break out of the pack and make as much—or even more—money than traditionally published authors. It’s not easy, though, especially as the market grows.

Still, there are downsides to “big.” All that support is expensive, and trade publishers can’t afford to take chances on books that aren’t guaranteed to sell millions of copies. Inevitably, good projects fall through the cracks. And if a book makes it through to print and doesn’t sell? The steadily chugging publishing train rolls over authors struggling to build an audience. Six months or a year, and the books are pulled from the shelves and pulped. After a while, the author’s contract is not renewed. It’s someone else’s turn in the sun.

In short, trade publishing not only does but must focus on the mass market. What about writers who have put in the necessary time to learn their craft but don’t produce something that millions of people want to read? These are the people who benefit from self-publishing, small presses, and author collectives.

Now I am the first person to admit that the problem with self-publishing is that, because it’s so easy, many people put out what are in essence first drafts. These first-time writers don’t intend to publish before the book is ready. The flush of finishing a first draft gives a writer a tremendous high. You can’t wait to get the book out into the world to soak up the praise you’re so sure it deserves.

Alas, the sad truth is that everyone’s first drafts stink. Yes, even the first drafts of published, professional authors. Sooner or later, the high dies away, the author receives comments and suggestions, and—assuming the book has not been published—the hard work of rewriting begins. Self-publishing too often short-circuits the essential revisions that turn a sketch of a book into a rich and rewarding reading experience.

But if the author resists that initial temptation to send the book out into the world and hires an editor or joins a (good) author collective or finds an innovative small press, that author can experience the benefits of “small.” A collective can define success as a hundred copies sold—or fifty. It can keep books in print throughout the author’s lifetime, building a reputation slowly as more books appear and readers discover them. It can take chances, because the stakes are low: mixing genres, taking the readers along less-traveled paths, publishing novels set in medieval Russia or modern Greece or the reigns of Tudor England that no one writes about because books about Anne Boleyn sell in the millions.

Some people hate joint enterprises. For them, author collectives are no solution. Even a small press is too constraining. Self-publishing is their most appealing option. Others instinctively tune into the zeitgeist and produce books that can and should be picked up by trade publishers, whose skills and experience can connect these authors to their mass-market readers. For those in the middle—the ones who don’t want to go it alone and like having the group’s imprimatur on their work and the knowledge that other writers have their backs—an author collective or a small press may be the ideal match. (The main differences between an author collective and a small press are the financial arrangements and a certain egalitarianism among the members.)

In short, publishing is a big pond, filled with many fish of different sizes and colors, all swimming along yet each in its own little eddy. Which is a lot more fun than a world where one size fits all, don’t you think?

Thanks to ClipArt Panda for the free fish that became the basis of this week’s image.

Published on December 12, 2014 06:00

December 5, 2014

Pre-Christmas Sale

So the early results of making two books available for Kindle Unlimited are in: more than twice as many borrows as e-book sales and three times as many e-book sales as print sales. So I’ve decided to experiment with a Kindle Countdown Deal to see what effect that has.

So the early results of making two books available for Kindle Unlimited are in: more than twice as many borrows as e-book sales and three times as many e-book sales as print sales. So I’ve decided to experiment with a Kindle Countdown Deal to see what effect that has. Remember: this is all research, as the two books in question—Desert Flower and Kingdom of the Shades—were a project that I had expected never to publish until I hunted down the books, revised them heavily, and decided to use them to test the results of going Kindle-only for e-books. I’m glad I revived them, because I had forgotten how much I loved their joint story—and I’m happy with how the revisions came out. But any amount I earn on them is more than I thought I’d make, which keeps my expectations suitably low. And if they attract new readers to my other novels, so much the better.

So here’s the deal. Beginning today and going through 8 AM PST on Monday, December 8,

Desert Flower

costs 99 cents. From Monday through 4 PM PST on December 12, the price rises to $1.99. After that, it returns to its regular price of $2.99.

Kingdom of the Shades

will cost 99 cents from 8 AM on Friday, December 12, through Monday, December 15, then go up to $1.99 until Friday, December 19. Then it too returns to $2.99. Closing times for the second promotion are the same as the first.

So here’s the deal. Beginning today and going through 8 AM PST on Monday, December 8,

Desert Flower

costs 99 cents. From Monday through 4 PM PST on December 12, the price rises to $1.99. After that, it returns to its regular price of $2.99.

Kingdom of the Shades

will cost 99 cents from 8 AM on Friday, December 12, through Monday, December 15, then go up to $1.99 until Friday, December 19. Then it too returns to $2.99. Closing times for the second promotion are the same as the first.Apologies to my friends in the UK, the only other Amazon.com marketplace that currently allows Kindle Countdown Deals. Amazon declared the price of the books (set by itself to equal the US dollar price) to be too low by 16p to qualify for a countdown deal. I changed the price to the minimum allowed for such a deal, but then I couldn’t set it up for thirty days. So bear with me, and I will run a countdown deal for you in January. Post-Christmas instead of pre-Christmas, but hey, you need an outlet for all that lovely cash you’ll get for the holidays, right?

So stock up while the price is right. Gift your friends for the holidays. If I get a good response, I’ll try other promotions. And whether you buy these books or not, I do wish you a lovely time preparing for whichever winter celebrations you celebrate.

By the way, the print versions are prettier. They just aren’t on sale. But you can still find them on the Amazon.com sites.

Published on December 05, 2014 13:34

November 28, 2014

Giving Thanks

Like many people at this time of year, I like to take a moment to be grateful for the good things in my life, which are precious and plentiful. I won’t bore you with a long list; I feel certain that you have a list of your own. Mine includes the usual suspects: Sir Percy and the Filial Unit, of course, but also other family members, friends, good health, a house I love and a pair of sweet cats ever ready to snuggle and play, a lovely neighborhood, a job I enjoy. But it also includes the time and ability to write, the community of writers who support (and critique) my efforts, a publishing climate that makes small presses like Five Directions Press possible and a career that taught me the skills I would need to make use of that climate—and, most of all, the strangers who take the time and spend their hard-earned cash to read and review the products of my imagination. I thank, too, the authors who agree to interviews with New Books in Historical Fiction, without whom the channel would die for lack of content, as well as the many people I have met and interacted with on social media, especially Facebook and Goodreads.

Like many people at this time of year, I like to take a moment to be grateful for the good things in my life, which are precious and plentiful. I won’t bore you with a long list; I feel certain that you have a list of your own. Mine includes the usual suspects: Sir Percy and the Filial Unit, of course, but also other family members, friends, good health, a house I love and a pair of sweet cats ever ready to snuggle and play, a lovely neighborhood, a job I enjoy. But it also includes the time and ability to write, the community of writers who support (and critique) my efforts, a publishing climate that makes small presses like Five Directions Press possible and a career that taught me the skills I would need to make use of that climate—and, most of all, the strangers who take the time and spend their hard-earned cash to read and review the products of my imagination. I thank, too, the authors who agree to interviews with New Books in Historical Fiction, without whom the channel would die for lack of content, as well as the many people I have met and interacted with on social media, especially Facebook and Goodreads.Last, I thank the characters who emerge from the ether or my subconscious, trusting me to bring their stories to life. I’ve had so much fun discovering them and the art of fiction over the last few decades as I went from reader to reader/writer. I hope to spend many more wonderful hours in their company.

So that’s my list. What’s yours?

And oh yes, hope you had a happy Thanksgiving!

Published on November 28, 2014 06:00

November 21, 2014

The Long Arm of the Law

As I have mentioned before, I am a “plot first” writer, which is rather amusing, since I outline my plots only sporadically and early on—or to get my characters out of a hole into which I have inadvertently painted them. But that’s in part because dreaming up plot points comes naturally to me, unlike characterization, which resembles the dragging of large roots from the soil.

As I have mentioned before, I am a “plot first” writer, which is rather amusing, since I outline my plots only sporadically and early on—or to get my characters out of a hole into which I have inadvertently painted them. But that’s in part because dreaming up plot points comes naturally to me, unlike characterization, which resembles the dragging of large roots from the soil.As a result, it shouldn’t surprise you to hear that I very much enjoyed my interview with Phillip Margolin, whose inventive and twisty plot for Worthy Brown’s Daughter kept me glued to the page. But strange as it may seem, we barely touched on his plot. That’s because in the interviews I always try to avoid spoilers, and Margolin’s plot has enough zigs and zags that the simplest question threatened to give away something crucial.

Instead, we discussed the law. Margolin spent years as a practicing criminal defense attorney, whereas I can’t remember making it through a single episode of Perry Mason. Sir Percy, my esteemed spouse, likes to joke that he got the lowest-ever-recorded scores on the LSAT, but at least he had the nerve to take the exam. Maybe that’s why I decided to specialize in medieval Russia, a time and place where the entire law code fit on a few sheets of paper.

But as Worthy Brown’s Daughter shows, justice had hurdles to overcome in the Wild West, too. In a territory where judges rode their circuits armed with six-shooters and attitude, looking for a handy field or tavern to hear cases, and where the government deprived entire segments of the population of their civil rights, winning a lawsuit or surviving a criminal accusation became a matter of skill, connections, or luck. Colorful characters, shady pasts, and courtroom dramas (some taking place in impromptu courtrooms) abound in this exploration of the U.S. Northwest during the early days of what is now the liberal state of Oregon. Let’s just say it was a lot less liberal then. To find out how, listen to the interview. It’s free, after all (although we love it if you choose to make a donation).

The rest of this post comes from the New Books in Historical Fiction site.

The year is 1860, months before the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War. Officially, slavery does not exist in Oregon, but the brand-new U.S. state has no compunction about driving most African-Americans out of its territory and violating the civil rights of the few permitted to remain. Worthy Brown, once a slave, has followed his master from Georgia on the understanding that he and his daughter will receive their freedom in return for helping their master establish his homestead near Portland. Indeed, the master, Caleb Barbour, does emancipate Worthy Brown as agreed. But he refuses to let go of Worthy’s fifteen-year-old daughter.

Worthy’s options for securing his daughter’s release are limited, but he obtains support from Matthew Penny, a recently widowed young lawyer just arrived from Ohio. Alas, Caleb Barbour is also a lawyer, wealthier and better connected than Matthew, and their clash of personalities unleashes a series of events that threatens not only their own lives but those of Worthy and his daughter. In 1860, Oregon is, after all, a state where even the local circuit judge relies on his pistol as much as or more than his law books.

Phillip Margolin, a former criminal defense lawyer, turns his attention to the past in Worthy Brown’s Daughter (HarperCollins, 2014). Although the story is loosely based on an actual law case from the Oregon Territory, the twists in the plot are Margolin’s own—and, as one would expect from the author of numerous bestselling contemporary literary thrillers, those twists and turns will keep you on the edge of your seat.

Published on November 21, 2014 06:00

November 14, 2014

50,000 Pins and Needles

Last week I wrote about Storyist, a specialized Mac/iOS program for novelists, screenwriters, and short-story writers, and bloggers. (I use it for this blog, for example). The context was National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), a fun contest/group writing exercise started several years ago. You might think, as a result, that I take part in NaNo.

Last week I wrote about Storyist, a specialized Mac/iOS program for novelists, screenwriters, and short-story writers, and bloggers. (I use it for this blog, for example). The context was National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), a fun contest/group writing exercise started several years ago. You might think, as a result, that I take part in NaNo.In fact, I do not. I tried it once, in 2010, and hated it. I did better with Script Frenzy, an offshoot of NaNo that seems to have fallen by the wayside since I tried it in 2009. So why do I no longer take part?

The main deterrent is not, as you might think, lack of time. To “win” at NaNo, you agree to produce 50,000 words in a month. That’s a tall order, unless you can ignore work, family, exercise, and sleep for thirty days. But I wrote the first draft of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel in three weeks, and that totaled 55,000 words. So it can be done, and I’ve done it. That’s not the problem.

Of course, it helps to feel inspired. When I sat down to type out NESP, I’d played with the story in my head for months, working out every detail. That kind of story doesn’t roll past every day, but there’s no rule that stops participants from planning their story in advance. Work out a plot and characters who will experience conflicts that speak to you, ask questions for which you’d like to know the answers, or borrow someone else’s universe (understanding that you’re writing not for publication but for practice), and you may come up with a book that writes itself. And if you don’t, just keep on slogging. You can always scramble the text before you send it in.

So then, what’s the problem? I love to write; I know what I need to do to succeed; I have enough experience to develop plot, characters, and conflict. What’s holding me back?

It’s the deadlines. That relentless little chart that shows how close I am to the goal, how many words I need to write today, what I will need to produce every day to finish, and how far I’m likely to fall behind November 30 if I don’t pick up the pace. I detest these charts with a passion, and there’s no way to turn them off. It’s a contest, after all, with a distinct goal and time frame. Writing 50,000 words in 30 days is the point of the whole exercise.

I’m not proud of this reaction, but I have to acknowledge it. The deadlines turn writing my novels, a hobby that has always brought true joy, into the equivalent of being a kid forced to eat her broccoli (and for the record, when not forced, I love broccoli). That November in 2010 I couldn’t wait to leave my desk. I procrastinated like crazy. During the week, I watched the wretched charts shoot my completion date farther into January. At the weekends, I crammed to catch up, writing paragraphs that were little more than nonsense syllables just to fill the space. And none of it was fun. The minute I hit 50,000 words I stopped, vowing never to subject myself to that again. And I never have.

I still think NaNoWriMo is a great idea—for other people, less obsessed with charts and progress. I wish all this year’s participants well. May they enjoy exploring the highways and byways of their subconscious minds and the antics of their characters. May they relish the journey whether they reach the endpoint or not. I will wave to them from the sidelines, where I will be writing The Swan Princess, free of charts.

(For those others, not me!)

Published on November 14, 2014 06:00

November 7, 2014

The Technology of Writing

In honor of National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), which began last Saturday, I decided to chat about options for producing novels, short stories, and screenplays. The technical aspects, if you like, of writing in the Internet Age.

Some people write longhand, in pencil on legal pads. Some pound out their manuscripts on electric or manual typewriters. I prefer a computer—the bad typist’s best friend. Specifically, I use Storyist, as I mentioned when this blog was brand-new.

Let me say right up front that Storyist won’t work for everyone. It runs on the Mac and on iOS devices, syncing files between computer and iPad with minimal fuss. Windows users have Scrivener—and other programs about which I know less. But their features are similar, if not exactly the same. So the question remains: Why pay for—and learn—a dedicated novel-writing program? Why not stick with a word processor? This post explains why.

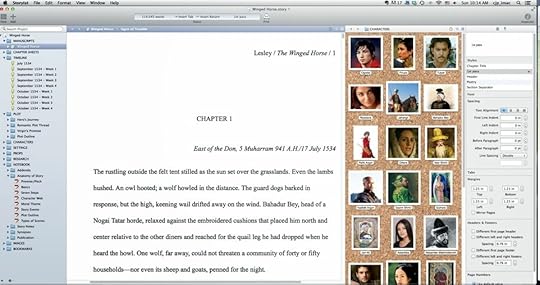

First, let me show you a screen shot.

Here you see the opening paragraph of The Winged Horse, combined with a photo gallery of my characters (I’m an intensely visual writer, so I love to imagine my characters while I’m telling their stories). On the left, you can see the Project View, which lists the different kinds of information that Storyist can hold: plot points, character and setting descriptions, research, notes and writing exercises, synopses and more. Already we’re in territory a word processor can’t touch, where I can write in one window while displaying other useful information in various ways.

The second screen shot shows a different view of The Winged Horse. Here you can see the chapters of the novel listed on the left. The character images still appear on the right, but the center manuscript has become a set of index cards representing chapter 1, each containing notes about the individual scenes—their purpose in the story, what they need to convey. If I were to double-click on a card, I would enter its collage, where I could write comments or drag pictures of the characters and settings associated with that section.

The third screen shot comes from The Swan Princess, the book I started this summer. So far, I have only about ten pages of text, which is sure to change as I write, so instead I’m showing the individual character sheet for Nasan, the heroine. It includes fields that came with the program (age, gender, eye color, hair color, build), fields that I defined (patronymic, character type, emotional makeup), my image of the character, and moments in her development—her character arc—linked to scenes in the story where that development takes place. I can show and hide these fields as I like. On the right I’ve displayed the novel’s main settings in outline mode, the third available option (besides text and grid—that is, index cards or photographs). On the left sits the usual list of folders, expanded to show different sets of information. I can get rid of windows, stack them on top of each other instead of side by side, or go into full screen mode and show only the manuscript.

Now, I’ll be the first to admit that multiple options have their downside. Learning a new program takes time you could have spent writing. It costs money (although less than some word processors). And just as it’s possible to workshop a novel to death, you can spend so much time plotting and constructing timelines, defining character traits, and collecting data that you forget to write the story. Everything in moderation, as they say.

But the upside is huge. When I can’t remember the color of a character’s eyes or how old that person is in this book, I click into the appropriate sheet, then back to my manuscript, without losing minutes or hours. I can search the entire project for facts, words, or phrases. (Did I overuse “gadget”? I can find out in a flash.) For calculating distances or sketching out a story, saving that great page I found on the Internet or reusing information from a previous book, Storyist is invaluable. When I get farther into the story and want to read it as a book, I can export an ePub or Kindle file; when I need to send chapters to my fellow writers, I save the manuscript as RTF; when I get that great idea right after I’ve shut down my computer, I type it into the iPad app and sync it back to Dropbox. If I need an overview of the story or a shorthand list of characters or settings, the outline view exists for that purpose—and I can export that, too, for distribution in Word. In all these ways, Storyist helps me make good use of my time.

I don’t bother with every bell and whistle. My character and setting sheets remain half-filled, I have yet to produce a complete set of plot points, and it’s a rare book that contains more than a few section sheets. My timeline is perennially out-of-date. Full screen mode leaves me cold, and I tend to forget the collages exist until I stumble over them. But the options I do use, I use every day, and I like knowing the others are there if I need them. When I’ve painted my protagonist into a corner, I set up index cards to walk her out. I add fields to track characters’ internal and external goals. If a chapter seems flat, sheets show where the conflict died. At the end of each book, I save a template to preserve all that work for the next one.

I stay in Storyist until the last minute, then export the RTF files to InDesign for final typesetting. Any revisions I make go back into the Storyist file, which in turn becomes the basis for the e-book versions. At the moment, I still do a bit of final formatting in Scrivener, which lets me remove first-line indents from chapter and section opening paragraphs. But otherwise I produce my novels entirely in Storyist.

If what I’ve said interests you, this is the perfect time to explore: NaNoWriMo participants can get a 25% discount in November. At any time, you can download a demo from the Storyist site. And if right now you need to focus on cranking out those 50,000 words, don’t forget that November 2015 will arrive before you know it. Plot out your next book and characters in Storyist, and you’ll be halfway to the finish line before NaNoWriMo even starts!

Disclaimer: I am not employed or otherwise financially compensated by Storyist Software, although I have voluntarily acted as a beta tester for the program since 2007.

Published on November 07, 2014 06:00