C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 51

June 27, 2014

Loosing the Reins

If you follow me on various social media, you have probably seen me posting this last week about the publication of The Winged Horse, the first of four planned sequels to The Golden Lynx and hence Legends of the Five Directions 2: East. If you regularly read this blog, you’ll know that I’m already hard at work on Legends 3: The Swan Princess. Thanks to last week’s staycation, I have a story for Legends 3 that works for me emotionally, although I need to complete certain kinds of research before I begin to write. Even at the best of times, my outlines exist solely to convince me that I have an initial state for my main character and a destination worth reaching, however long and winding the road. As soon as I put fingers to keyboard and type, the story morphs around me. I may try to plot, but I am a seat-of-the-pants writer (pantser) by heart.

If you follow me on various social media, you have probably seen me posting this last week about the publication of The Winged Horse, the first of four planned sequels to The Golden Lynx and hence Legends of the Five Directions 2: East. If you regularly read this blog, you’ll know that I’m already hard at work on Legends 3: The Swan Princess. Thanks to last week’s staycation, I have a story for Legends 3 that works for me emotionally, although I need to complete certain kinds of research before I begin to write. Even at the best of times, my outlines exist solely to convince me that I have an initial state for my main character and a destination worth reaching, however long and winding the road. As soon as I put fingers to keyboard and type, the story morphs around me. I may try to plot, but I am a seat-of-the-pants writer (pantser) by heart.The Swan Princess will, no doubt, become the subject of many future posts. This one constitutes my farewell to Ogodai and Firuza, Tulpar and Jahangir, and the elders (and juniors) of their horde. They are not gone forever, of course—that is the great advantage of a series. But even as they return, if they do return, in future books, they will not be quite the people with whom I have spent the last two years. They will grow and change, as Nasan and Daniil grew and changed in The Winged Horse and must change again for The Swan Princess. The eighteen-year-old Ogodai and Firuza, their fears and uncertainties, their helpful (or not so helpful) companions—these versions of my characters will cross my path again only as I re-read their stories to reconnect with them before spinning out their personalities into future selves.

I find it surprisingly difficult to let them go. Excitement and adventure characterize every new novel, yet I know that one reason my initial outline for The Swan Princess was so long and complex (as described in “Writing Process Blog Hop”) had to do with my own reluctance to let certain characters’ stories vegetate until Legends 4, where they belong. These characters kept sneaking into my plans, marching around in my head and refusing to go to sleep, despite my best efforts to focus on the new.

But for better or worse, The Winged Horse is now out in the world—where some readers will (I hope) love it and others not care for it so much, where it must sink or swim on its own. I can go back to reading both for pleasure and for research; ponder the new story and characters (some revived from The Golden Lynx, where they fought their temporary seclusion just as tenaciously as the present batch); spend time catching up on GoodReads, BookLikes, Facebook, Pinterest, and the like; and devote more time to this blog than I managed to do in the last three weeks of obsessive proof reading, corrections, uploads, and announcements.

If you’d like to see what the fuss is about, you can find the first few paragraphs below. If you have an e-reader, you can download samples for Kindle and iBooks, as well as at the book page on GoodReads and the B&N nook store. If you don’t have an e-reader, Amazon.com allows you to “look inside” the print version. Links to the various formats are at my website and my publisher’s website. The first link is a bit easier to navigate because it includes only my three novels; the second may expose you to other titles worthy of your attention.

And if you like the story (or even if you don’t—I believe readers have every right to their opinions), please consider leaving a review at your favorite book site. It will help others to decide whether they, too, would like to explore the sixteenth-century steppe in the company of Ogodai and his associates.

I swear, it is the purest coincidence that Russia decided to annex Crimea, thus throwing Tatar politics and history unexpectedly into the news....

CHAPTER 1

East of the Don, 5 Muharram 941 A.H./17 July 1534

The rustling outside the felt tent stilled as the sun set over the grasslands. Even the lambs hushed. An owl hooted; a wolf howled in the distance. The guard dogs barked in response, but the high, keening wail drifted away on the wind. Bahadur Bey, head of a Nogai Tatar horde, relaxed against the embroidered cushions that placed him north and center relative to the other diners and reached for the quail leg he had dropped when he heard the howl. One wolf, far away, could not threaten a community of forty or fifty households—nor even its sheep and goats, penned for the night.The quail leg disappeared in a bite or two. Bahadur licked his lips and savored the lingering richness on his tongue—molten fat flecked with salt, gaminess mixed with herbs.A few too many herbs, in fact. That tinge of bitterness, although not unpleasant in itself, could easily be overdone. A point to bring up with the cooks tomorrow morning.Platters of food, stripped almost bare, dotted the felt mats laid over the rugs that protected the diners from the thin grass of the steppe. Elaborately decorated, many of the felts bore the stylized form of the winged horse, Bahadur’s banner. His camp, his home: here among family and friends, even a bey could lay down the burdens of leadership at the end of a long day.In addition to the quail, always a favorite, the platters held roast venison and flat bread, hard and soft cheeses, pomegranates and nuts. Bahadur had drunk deep from pitchers filled with frothy mare’s milk and shared cups from a cask of wine, warm with the sunshine of the Crimean hills. One good thing left behind by that scoundrel Tulpar. Its taste lingered on the tongue in happy marriage with the quail.He considered eating more, but his sash already felt tight to the point of discomfort, and the light slanting through the smoke hole reinforced the message delivered by the quieting of the herds. In the steppe, the midsummer sun hid itself for so short a time that if he did not retire to his private tent to sleep as soon as night fell, he would find himself on horseback again before his muscles ceased to ache. Once he had caroused the night away, as his son Jahangir did, but no more. The counsel of age and wisdom told him he had eaten enough, drunk enough. Time to rest.Outside, the wind was picking up. “Hear that?” he said to his chief herdsman, seated not far from the door. “Better get the lambs and the weaker animals under cover. It will storm before morning. Check the pens, too.”The herdsman bowed in acknowledgment and ducked from the tent without more ado. A good man, knew his business. Always placed the needs of the animals first, aware that the tribe depended on the herds.Time for Bahadur, too, to go before the weather changed.

Published on June 27, 2014 15:27

June 20, 2014

There’s Always Been an England?

“There’ll always be an England,” people say, quoting a patriotic song from 1939. But what follows from that perception of England as eternal is the idea that England will not only continue to exist but has always existed: “this precious stone set in the silver sea” (Shakespeare, Richard II). We speak of Celtic Britain, Roman Britain, the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans—as if these entities were like scenes from a school pageant, interchangeable except for their ethnicities and costumes. Exit Jutes, stage left. Enter William the Conqueror, stage right.

“There’ll always be an England,” people say, quoting a patriotic song from 1939. But what follows from that perception of England as eternal is the idea that England will not only continue to exist but has always existed: “this precious stone set in the silver sea” (Shakespeare, Richard II). We speak of Celtic Britain, Roman Britain, the Anglo-Saxons and the Normans—as if these entities were like scenes from a school pageant, interchangeable except for their ethnicities and costumes. Exit Jutes, stage left. Enter William the Conqueror, stage right.In fact, as James Aitcheson noted during my interview with him in March, and as Bernard Cornwell underlines in this month’s interview, England was just as much a project, in its way, as the United States of America. It did not emerge overnight, along a predetermined path. It required centuries of careful construction that might, had events taken even a slightly different turn, have produced something rather different: Greater Denmark, perhaps. If it had, most of us here in North America would be speaking Danish as well.

So follow along, as Bernard Cornwell and I explore his development as a writer, the “little story” represented by Uhtred of Bebbanburg, and the vast background tapestry that is the idea, the emergence, and the eventual consolidation of England as a nation. Then read The Saxon Tales, beginning with The Last Kingdom, because the story of Uhtred’s England is not yet finished. (As a bonus, you will also learn the correct pronunciation of Uhtred’s motto, Wyrd bid ful araed.)

The rest of this post comes from the New Books in Historical Fiction site.

As fans of Uhtred of Bebbanburg know, England in the ninth and tenth centuries is just an idea—a hope held by the kings of Wessex that they may someday unite the lands occupied by the Angles and Saxons, most of whom live under the control of Danish invaders. Not only England’s future hangs in the balance: spurred by King Alfred the Great of Wessex, Christianity has spread rapidly among the Saxons, but that early success threatens to crumble if the pagan Danes complete their conquest as planned.

Enter Uhtred of Bebbanburg, a Northumbrian lord of Saxon descent, raised by the Danes and defiantly pagan, a warrior and leader of men. The rulers of Wessex can’t decide what to make of him, but they grudgingly admit that they need his help. As victory follows victory, Uhtred gains and loses estates, marries and buries wives, takes lovers both peasant and royal, and goes from battle to battle, dragging his sons in his wake. Uhtred has a cherished dream of his own, to reclaim Bebbanburg—his birthright, stolen from him by his uncle during Uhtred’s Danish childhood.

In The Pagan Lord, Uhtred has reached his mid-fifties, an advanced age for the tenth century. Much has changed with the death of Alfred the Great, and the new king of Wessex believes he can dispense with Uhtred’s services. When Uhtred’s eldest son announces that he has not only converted to Christianity but become a priest, Uhtred’s rage leads him to disinherit that son and to kill the abbot who tries to intervene. The Wessex court and Church strip Uhtred of his rights and banish him. Meanwhile, a hidden adversary has abducted the wife and children of the Danish leader Cnut and pinned the crime on Uhtred. Cnut retaliates by raiding and burning Uhtred’s estate, killing most of the inhabitants. With little to lose and everything to gain, Uhtred gathers his three dozen surviving warriors and sets off to storm the impregnable fortress of Bebbanburg.

Bernard Cornwell has more awards and bestselling books than we can possibly list here. The Pagan Lord—and The Saxon Tales of which it is a part—opens a door onto a long-forgotten and under-appreciated past in a way that offers pure entertainment. Warning: you will lose sleep trying to find out what happens next.

Published on June 20, 2014 06:30

June 13, 2014

Travels in Time and Space

It’s been a while since I wrote a post on images and where to find them. I did a whole series in 2012, giving information on collections that in many cases have only improved since then. In others it’s already out-of-date: Photos.com has blended into ThinkStock and no longer offers a less-expensive alternative to Shutterstock, for example. But I just found another enormous repository of art and photography, so I decided to share the news.

The first post in that 2012 series, “The Nation’s Photo Album,” listed some of the major collections available digitally via the U.S. Library of Congress, including 1,100 photographs of classic Russian architecture taken by William Craft Brumfield, professor of Slavic Studies at Tulane University and a noted expert on the architectural history of Russia and the surrounding lands. Brumfield also worked on the Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii collection of original color photographs from 1915, restored and housed at the Library of Congress.

But the main part of Professor Brumfield’s collection, I discovered recently, is at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), in Washington, DC. The NGA holds thirteen million images in the form of photographs, slides, negatives, microforms, and digital files—including almost fifty-five thousand donated by Professor Brumfield, compiled during his forty years of trekking around the former USSR recording buildings old, new, restored, and decaying. These priceless photographs are just a part of its collection, which focuses primarily on the art and architecture of Western Europe.

So what can you find if you visit the NGA site? A good place to start is with the NGA Library Image Collections Features. There, if you scroll down, you can see a heading, “Travels Across Russia,” and (at the moment), four images for 1889, Ekaterinburg, Murom, and Torzhok. Click on one—I chose Torzhok, where my antagonist in The Swan Princess plans to establish himself just as soon as he identifies a way out of his Arctic monastery prison.

A window opens with a short history of the town and a set of slides. Clicking on a slide opens the entire set for that feature, with (in this case) informative captions for each slide offering dates, descriptions, and copyright information, if any. A navigation bar to the left shows a link to the Image Collections Catalogue; enter a search term, and you can export or print the results. You can also store images in a light box for easy retrieval. The site is responsive and easy to use, beautifully designed.

And this is just the Library collections. Click on National Gallery of Art in the top left of the navigation band at the top, and another window opens onto the collection, with its own features and search box and collections of clickable tiles. (Hint: To get back to the Library Image Collections, click on Research in the top navigation bar, then Library.)

And this is just the Library collections. Click on National Gallery of Art in the top left of the navigation band at the top, and another window opens onto the collection, with its own features and search box and collections of clickable tiles. (Hint: To get back to the Library Image Collections, click on Research in the top navigation bar, then Library.)The site offers access to exhibitions, paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, photographs, pictures of everyday objects, multimedia presentations, and more—all searchable, all free to download, and much of it usable for both commercial and noncommercial purposes. The NGA maintains an open access policy, which states, “Users may download—free of charge and without seeking authorization from the Gallery—any image of a work in the Gallery’s collection that the Gallery believes is in the public domain and is free of other known restrictions.” It requests only that you add the line “Courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington,” to help others locate the collections. But you do need to check the individual images: artists and photographers do not surrender their copyright merely by donating their images to the gallery.

So next time you’re looking for that perfect image, take a trip in time and space through the National Gallery of Art. You won’t be disappointed, wherever your interests lie.

And if, like me, you particularly enjoy pictures of Russia, another good site to check is Rossiiskaia gazeta’s online “Russia Beyond the Headlines” series, which includes Professor Brumfield’s ongoing journeys across that vast and surprisingly uncharted territory. A recent trip to the Russian North (where my Swan Princess antagonist has been reluctantly holed up) is a good place to start. It includes a map of the area pictured and links to other posts in the series.

For best results, click on the icon with the four arrows to the bottom right of the pictures and enjoy the full-screen slide show that appears.

If you'd like to know more about the thousand-year history of Russian architecture in general, you can also try Brumfield’s books, beginning with Gold in Azure.

All images courtesy of National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. The two pictures of the exterior and interior of the 1717 Church of the Ascension in Torzhok (alas, built too late for my characters to have seen it!) reproduced with permission from William Craft Brumfield.

Published on June 13, 2014 12:14

June 6, 2014

Sovereign of Stars

Let me say immediately that the title of this post is not mine. It is in fact the title of the third book in Libbie Hawker’s (L. M. Ironside’s) The She-King, a four-part series about Hatshepsut of Egypt. It’s a great title, and this post is about Libbie and her books, so I am stealing it, with acknowledgment but otherwise without a qualm.

Let me say immediately that the title of this post is not mine. It is in fact the title of the third book in Libbie Hawker’s (L. M. Ironside’s) The She-King, a four-part series about Hatshepsut of Egypt. It’s a great title, and this post is about Libbie and her books, so I am stealing it, with acknowledgment but otherwise without a qualm.You may not be expecting a post announcing another New Books in Historical Fiction (NBHF) interview just yet. Since I began conducting these interviews in November 2012, I have posted regularly around the middle of each month. But as I mention in the podcast (and elsewhere on this blog), that’s about to change. Libbie has agreed to join me as a co-host for NBHF, beginning in early July. So from now on, new conversations will appear on the Web and in your podcast app (if you subscribe) every couple of weeks.

It’s hard to escape the news that self-publishing, writers’ cooperatives, and other types of small groups taking advantage of CreateSpace, Lulu, Kindle Direct Publishing, Nook Press, the iBookstore, and various other publishing platforms open to anyone with a computer and the skills to produce the appropriate files have grown rapidly in the last few years. In 2011, when I first considered rewriting The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel as an experiment in small-group publishing, I knew only one other writer who had taken that route. That was about the time when Libbie released The Sekhmet Bed (The She-King: Book 1). As she explains in the interview, that timing really worked for her in terms of attracting attention in what was then a much smaller field. As a result, she managed to get enough traction with that first book that she has recently quit her job to write full-time—an achievement that few self-published authors and, in fact, few historical novelists can claim.

The main focus of the interview, though, is on ancient Egypt, as it appears in The She-King series and in reality, to the extent we can determine a reality that is now more than 3,500 years in the past. As you may have guessed from my posts about Elizabeth Peters, “Crocodiles, Mummies, Ramses, and More” and “The Sands of Time,” I love books set in ancient Egypt, especially the reign of Hatshepsut, who distinguished herself by being one of the few women to rule not as a queen but as pharaoh. In richly detailed prose, this series presents lively and believable characters facing compelling problems in pursuit of a goal that is at once historical and modern: the drive of a young woman to reach a pinnacle of power appropriate to her ability rather than settle for the constraints imposed on her by birth.

Listen to the interview. Read Libbie’s books. And friend or follow us on social media to learn about our new biweekly interviews as soon as they go live. You can find my links under the “About Me” tab and to the right. Hers are available on her website.

The rest of this post is abridged (to avoid duplication) from the New Books in Historical Fiction site.

Egypt in the Eighteenth Dynasty seems both impossibly distant in time and disconcertingly present. Over 250 years, the dynasty produced several of the rulers best known to modern Western culture: Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, Tutankhamen (Tut), and Hatshepsut, the most famous of the handful of women who ruled Egypt as pharaoh.

The Sekhmet Bed begins a few years before Hatshepsut’s birth, with the death of Pharaoh Amenhotep I in 1503 BCE. He leaves two daughters, Mutnofret and Ahmose, to marry—and therefore legitimate—the next pharaoh. The marriage surprises neither of them, but in an unexpected twist the thirteen-year-old Ahmose is proclaimed Great Royal Wife while her older sister has to settle for second place. Mutnofret does not take her perceived demotion lying down, and she uses her greater maturity to seduce the pharaoh. She is soon fulfilling the main obligation of a queen: to bear royal sons. But Ahmose, a visionary, has the ear of the gods—the reason she received the title of Great Royal Wife in the first place. And the gods will decide whether Ahmose or her sister will bear the next pharaoh.

The Sekhmet Bed begins a few years before Hatshepsut’s birth, with the death of Pharaoh Amenhotep I in 1503 BCE. He leaves two daughters, Mutnofret and Ahmose, to marry—and therefore legitimate—the next pharaoh. The marriage surprises neither of them, but in an unexpected twist the thirteen-year-old Ahmose is proclaimed Great Royal Wife while her older sister has to settle for second place. Mutnofret does not take her perceived demotion lying down, and she uses her greater maturity to seduce the pharaoh. She is soon fulfilling the main obligation of a queen: to bear royal sons. But Ahmose, a visionary, has the ear of the gods—the reason she received the title of Great Royal Wife in the first place. And the gods will decide whether Ahmose or her sister will bear the next pharaoh.Libbie Hawker brings this long-gone but fascinating period alive in a tale of two sisters forced into conflict by the need to secure an empire and a dynasty.

Published on June 06, 2014 13:25

May 30, 2014

Challenge Update

So back in January, I announced that I planned to take part in two challenges for 2014, the History Challenge: A Sail to the Past, and the Reduce the TBR Mountain Challenge (which I sorely needed, since I have tons of unread books lying everywhere, including on my e-reader). My friend Courtney J. Hall called me crazy—and she was right. But since it’s now more than a third of the way through the year, how have I done?

So back in January, I announced that I planned to take part in two challenges for 2014, the History Challenge: A Sail to the Past, and the Reduce the TBR Mountain Challenge (which I sorely needed, since I have tons of unread books lying everywhere, including on my e-reader). My friend Courtney J. Hall called me crazy—and she was right. But since it’s now more than a third of the way through the year, how have I done?On the History Challenge, I passed seven books (the Historian level) ages ago, although I have not gone much beyond that due to other commitments, mostly interviews and my efforts to get The Winged Horse ready for publication (stay tuned for the announcement: it’s now less than two weeks away). These seven books were:

1. Stephen M. Norris and Willard Sunderland, Russia’s People of Empire: Life Stories from Eurasia, 1500 to the Present

2. Nancy Shields Kollmann, Crime and Punishment in Early Modern Russia

3. Bernard Bailyn, The Barbarous Years

4. John Keegan, The Face of Battle

5. Ian Mortimer, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Elizabethan England

6. Elizabeth Kendall, Balanchine and the Lost Muse: Revolution and the Making of a Choreographer

7. Christine Ezrahi, Swans of the Kremlin: Ballet and Power in Soviet Russia

I also read John Keegan’s Soldiers: A History of Men in Battle; John A. Lynn’s Women, Armies, and Warfare in Early Modern Europe; Barbara Mertz’s Red Land, Black Land; and at least three books in Russian that qualify as history but aren’t readily searchable on GoodReads or Amazon.com, so I left them out of the challenge list.

For the Reduce the TBR Mountain challenge, I had set a level of 24 books (Mont Blanc). The seven books listed above, plus Keegan’s Soldiers and Lynn’s book on women and warfare, all count for the TBR challenge, giving me nine books going in. In addition to those, I have read:

10. Tasha Alexander, Behind the Shattered Glass

11. Jason Goodwin, The Janissary Tree

12. Bernard Cornwell, The Last Kingdom

13. Bernard Cornwell, The Death of Kings

14. JJ Marsh, Raw Material

15. Cathy Marie Buchanan, The Painted Girls

16. Deanna Raybourn, Silent in the Grave

17. Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago

And I am about a quarter of the way through Silvia di Natale’s wonderful Kuraj, about a girl from the steppe who is sent to Germany—why remains unclear.

So one-third of the year down, and 1.75 challenges completed. If the six books I read for interviews counted (but they don’t, because most are advance review copies), I’d be done by now.

Either I really am crazy, or I love to read—I suspect it’s a bit of both!

Published on May 30, 2014 13:11

May 23, 2014

Lives in Bondage

Last week I posted about my interview with Tara Conklin. Her novel, The House Girl, reveals from the inside the daily experience of a slave, in prose that is simultaneously beautiful and shattering—at times shattering precisely because of its beauty.

In the United States, the tendency to sweep the topic of slavery under the rug arises in part from embarrassment. We are the democracy built to a significant degree on bondage, the land of the free—unless you happen to be born black or brown or female, in which case God help you. Thomas Jefferson, the articulator par excellence of democratic principles, had six children with the enslaved half-sister of his wife, Sally Hemings, who achieved her freedom only with his death. The hypocrisy is inescapable.

Slaves Steadying the Khan's Wagon

Slaves Steadying the Khan's Wagon

Screen shot from Nomad: The Warrior (2005)

But slavery was not an institution unique to the antebellum South. The domestic servants in my Legends of the Five Directions series are all slaves. Grusha—a major secondary character and future heroine—is a slave. The nomadic Tatar horde that forms the setting for The Winged Horse owns slaves. Tatar khans of the period supported themselves largely through slave raids, scooping up thousands of young Slavs each year for sale in Istanbul. Hürrem, better known as Roxelana, who managed harem politics with such skill that she eventually persuaded the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to marry her, was a Ukrainian noblewoman captured in one such Tatar raid.

But is slavery the same everywhere? Scholars have traditionally regarded the version that prevailed in the U.S. South as unusually harsh, not least because its racist underpinnings made it impossible to escape. As the recent film Twelve Years a Slave highlights, even after it became illegal to import slaves from abroad, free blacks could be captured and enslaved, purely on the basis of their skin color. The social distance between slave and free was much less in Russia, where slaves resembled their owners in appearance and in culture. One might not confuse a slave with a noble, but one could not easily distinguish between slave and peasant or slave and artisan. Nor were the poor as free as they might have liked: they bore heavy obligations in taxes and tolls, and of necessity their lives focused on subsistence. Indeed, slavery functioned in Russia as a kind of social welfare system. Grusha ends up in the Kolychev household because her parents cannot afford to feed all their children, so they sell the girls and keep the boys, whom they consider more useful on the farm.

Even so, the life of a slave can’t have been pleasant. The things that Tara Conklin’s slave character Josephine dreams of being able to do—eat when she’s hungry, love whom she chooses, hang a painting of hers on the wall of a room that belongs to her—would also be on the lists of Grusha and her fellow servants. Indeed, Grusha has a list of her own: “Why should she not dress in satins and velvets? Ride in palanquins? Eat delicious food whenever she felt hungry?” (The Golden Lynx, 163–64). The only answer is because she was not born to the right family. Poverty, not skin color, keeps her in her place.

Nobleman's Servant (Slave)

Nobleman's Servant (Slave)

From the Mayerburg Album of 1661

Of course, Nasan, the heroine of The Golden Lynx, doesn’t control her life either, despite being a khan’s daughter. Noblemen could no more choose their professions than peasants; Daniil’s brother, Boris, would have liked to paint icons, but society demanded he go to war. Russian nobles referred to themselves as slaves of the ruler, a custom that horrified the rare Western visitor. And the word now commonly translated as “sovereign” in fact means “master,” in the sense of slave owner. The element of hypocrisy was missing: duty far outweighed freedom as the primary value of Russian traditional society. Yet even in a world where according to popular lore, “he who wears the keys is a slave,” it must have been much better to be the master or mistress, warm and well fed—if not exactly comfortable (comfort is largely a modern, “bourgeois” notion; our ancestors cared more about prestige and honor)—and able to call the shots in one’s household. In that sense, lives in bondage look much the same wherever and whenever we find them.

In the United States, the tendency to sweep the topic of slavery under the rug arises in part from embarrassment. We are the democracy built to a significant degree on bondage, the land of the free—unless you happen to be born black or brown or female, in which case God help you. Thomas Jefferson, the articulator par excellence of democratic principles, had six children with the enslaved half-sister of his wife, Sally Hemings, who achieved her freedom only with his death. The hypocrisy is inescapable.

Slaves Steadying the Khan's Wagon

Slaves Steadying the Khan's WagonScreen shot from Nomad: The Warrior (2005)

But slavery was not an institution unique to the antebellum South. The domestic servants in my Legends of the Five Directions series are all slaves. Grusha—a major secondary character and future heroine—is a slave. The nomadic Tatar horde that forms the setting for The Winged Horse owns slaves. Tatar khans of the period supported themselves largely through slave raids, scooping up thousands of young Slavs each year for sale in Istanbul. Hürrem, better known as Roxelana, who managed harem politics with such skill that she eventually persuaded the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent to marry her, was a Ukrainian noblewoman captured in one such Tatar raid.

But is slavery the same everywhere? Scholars have traditionally regarded the version that prevailed in the U.S. South as unusually harsh, not least because its racist underpinnings made it impossible to escape. As the recent film Twelve Years a Slave highlights, even after it became illegal to import slaves from abroad, free blacks could be captured and enslaved, purely on the basis of their skin color. The social distance between slave and free was much less in Russia, where slaves resembled their owners in appearance and in culture. One might not confuse a slave with a noble, but one could not easily distinguish between slave and peasant or slave and artisan. Nor were the poor as free as they might have liked: they bore heavy obligations in taxes and tolls, and of necessity their lives focused on subsistence. Indeed, slavery functioned in Russia as a kind of social welfare system. Grusha ends up in the Kolychev household because her parents cannot afford to feed all their children, so they sell the girls and keep the boys, whom they consider more useful on the farm.

Even so, the life of a slave can’t have been pleasant. The things that Tara Conklin’s slave character Josephine dreams of being able to do—eat when she’s hungry, love whom she chooses, hang a painting of hers on the wall of a room that belongs to her—would also be on the lists of Grusha and her fellow servants. Indeed, Grusha has a list of her own: “Why should she not dress in satins and velvets? Ride in palanquins? Eat delicious food whenever she felt hungry?” (The Golden Lynx, 163–64). The only answer is because she was not born to the right family. Poverty, not skin color, keeps her in her place.

Nobleman's Servant (Slave)

Nobleman's Servant (Slave)From the Mayerburg Album of 1661

Of course, Nasan, the heroine of The Golden Lynx, doesn’t control her life either, despite being a khan’s daughter. Noblemen could no more choose their professions than peasants; Daniil’s brother, Boris, would have liked to paint icons, but society demanded he go to war. Russian nobles referred to themselves as slaves of the ruler, a custom that horrified the rare Western visitor. And the word now commonly translated as “sovereign” in fact means “master,” in the sense of slave owner. The element of hypocrisy was missing: duty far outweighed freedom as the primary value of Russian traditional society. Yet even in a world where according to popular lore, “he who wears the keys is a slave,” it must have been much better to be the master or mistress, warm and well fed—if not exactly comfortable (comfort is largely a modern, “bourgeois” notion; our ancestors cared more about prestige and honor)—and able to call the shots in one’s household. In that sense, lives in bondage look much the same wherever and whenever we find them.

Published on May 23, 2014 11:38

May 16, 2014

Echoes of the Past

Yesterday I had the great pleasure of interviewing Tara Conklin for New Books in Historical Fiction. Her book, The House Girl, appeared last year. I learned about it, as I hear about many interesting books, from National Public Radio. I think it was the Sunday Morning Edition, but I no longer feel certain of that. Whatever the show, I knew at once that this was a book I wanted to read and an author I would love to interview. And since the paperback version came out a few months ago, this seemed like the perfect time.

Yesterday I had the great pleasure of interviewing Tara Conklin for New Books in Historical Fiction. Her book, The House Girl, appeared last year. I learned about it, as I hear about many interesting books, from National Public Radio. I think it was the Sunday Morning Edition, but I no longer feel certain of that. Whatever the show, I knew at once that this was a book I wanted to read and an author I would love to interview. And since the paperback version came out a few months ago, this seemed like the perfect time.The book was everything I had imagined and more: beautifully written, it moves seamlessly back and forth between past and present, contrasting the lives of two young women: Lina, a 24-year-old lawyer in 2004 New York; and Josephine, a 17-year-old slave experiencing what she hopes will be her last day on a Virginia tobacco plantation in 1852. Although Josephine works in the house, not under the even harsher conditions that prevail in the tobacco fields, she suffers plenty of indignities, small and large, against which she has no defense except to immerse herself, when possible, in the paintings that her mistress permits her to make. And it is those paintings that eventually bring Josephine to Lina’s attention, raising the possibility of a well-deserved if long-overdue vindication of an old wrong.

The rest of this post comes from the New Books in Historical Fiction interview page:

Lina Sparrow can’t believe her luck when the boss at her fancy New York law firm offers her a once-in-a-lifetime chance: find a suitable plaintiff for a class-action suit to be lodged against the U.S. government and fifty rich corporations that profited from slave labor before the Civil War. The wealthy technocrat intent on pushing this suit for reparations claims he has a deal that will protect Lina’s law firm from going head to head against the government, and the case seems guaranteed to generate lots of publicity and a lovely bag of cash for the law firm. But the pressure is on: Lina has only a few weeks to find the right person and convince him or her to play along.

Luck again appears to favor her when a friend of her artist father alerts her to a recent controversy surrounding the paintings of Luanne Bell, a plantation lady from the 1850s whose art portrays her slave laborers with extraordinary complexity and compassion. Are the paintings Luanne’s, or the work of her house girl Josephine? And if Lina can prove that Luanne has received credit for Josephine’s work for the last century and a half, can she also find a descendant who can serve as living evidence of the devastating damage inflicted by slavery?

The House Girl moves deftly back and forth between past and present as Lina works to trace the history of one young girl enslaved on a Virginia tobacco plantation while fending off challenges posed by her coworkers, the man who may be Josephine’s descendant, and even her own past. Tara Conklin’s debut novel hit the bestseller lists within weeks of its release. You’ll have no trouble figuring out why.

Published on May 16, 2014 12:48

May 9, 2014

Duels of Honor

Something new and different this week. Pauline Montagna, who had planned to participate in the Writing Process Blog Hop on March 31, has organized a blog tour to celebrate the release of her novel The Slave, pictured here. You’ll find more information about the book, Pauline, and her website—including a time-constrained offer for a free e-book—at the end of the post. The Slave is set in Renaissance Italy, where, as Pauline notes, dueling in the sense that most of us think of it first developed.

Something new and different this week. Pauline Montagna, who had planned to participate in the Writing Process Blog Hop on March 31, has organized a blog tour to celebrate the release of her novel The Slave, pictured here. You’ll find more information about the book, Pauline, and her website—including a time-constrained offer for a free e-book—at the end of the post. The Slave is set in Renaissance Italy, where, as Pauline notes, dueling in the sense that most of us think of it first developed.The judicial duel was known in medieval Russia, too, but the duels of honor described in Pauline’s post did not exist there at that time. The custom, imported from the West like so much else after the reforms of Peter the Great (1682/89–1725), took hold in Russia in the early nineteenth century. Alexander Pushkin’s novel in verse Eugene Onegin is arguably the most famous literary example of the trend. Tragically, Pushkin himself died in a duel defending his wife’s honor in 1837.

And now, take it away, Pauline!

The Duel of Honor The Italians invented the duel of honor during the late Middle Ages and Renaissance and were the most prolific both in resorting to such measures and in their writings on the subject. For Italians, a duel was not just a fight between two men but a highly sophisticated and formalized judicial procedure defined and regulated by a set of rules as complex and binding as those of any court of law. In fact, the first treatises that appeared on the subject of dueling, as early as the fourteenth century, were written by Italian jurists.

The duel of honor grew out of practices that date back to the most distant historical times. The earliest type of duel was the state duel, where representatives of opposing armies or factions would decide the winner in one-to-one combat between champions. The judicial duel dates from the Dark Ages and was introduced into Italy by the Lombards. This state-sanctioned duel would be fought to determine the guilt or innocence of a man accused of a crime. The accused would fight his accuser under the auspices of his lord who would decree the appropriate punishment for the loser, be it the accused who would have to suffer for his crime or the accuser who would be punished for perjury.

By the twelfth century, the judicial duel had fallen into disuse, but out of it had grown the duel of honor, fought now to prove or disprove an accusation of a dishonorable act. Duels could also be fought to acquire fame, out of sheer hatred, and, of course, over the love of a woman. However, it was only the formal public duel fought on a point of honor that was considered ethical and justifiable. Though tacitly endorsed by both state and church authorities, official canon law decreed all dueling unlawful and deemed the losing party a suicide and the winner a murderer.

The duel would begin with an accusation or an insult. The offended party would then challenge the other to a duel. Which party was the official challenger could sometimes be disputed if, perhaps, several insults were exchanged, or the duel was deliberately provoked by a man who considered himself already injured. Their friends would beg them to fight only as a last resort and find a peaceful solution such as an apology or a retraction, or by providing proof of the accused party’s innocence or guilt, for no duel could be fought over a manifestly true accusation.

Duels of honor could be fought only among the nobility and knights. It was considered dishonorable to challenge a man of lower rank. A man of lower rank could challenge one of higher rank, but the man of higher rank had the privilege of refusing the challenge. While a challenger would be expected to fight on his own behalf, the challenged party could bring in a substitute, except in the case of an accusation of a crime that could incur the death penalty. One could also fight of behalf of an injured party that was unable to defend themselves.

The challenged party had the choice of arms, though, as noted earlier, which party had that right might be disputed. When there was any doubt, the choice would go to the offended party. The parties must find a suitable field on which to fight, then ask permission of the local lord to hold the duel. The duel would be presided over by a judge, who would be either the local lord or a man chosen by both parties. After trying to bring about a peaceful resolution, the judge would ensure the duel was fought according to the rules and declare the winner.

A practice which originated in Italy was the calling in of seconds or padrini. Preferably men of experience, moral courage, justice, and urbanity, the seconds’ duties were to inspect the field and the opponent’s equipment, ensure his principal received his rights and seek to resolve any questions in his principal’s favor even if this led him into a dispute with the opposing second, a dispute which might also be resolved by a duel on a later date. Seconds might also be called on to avenge their principal’s death.

Before the duel could be fought, the judge had to ensure physical equality between the opponents. This might involve fasting or bloodletting by the stronger man, or tying one arm up if the opponent was one-armed or covering an eye (some advocated putting out the eye) if the opponent was one-eyed. As the duel could also be fought on horseback and in armor, they, too, should be equivalent so that no man had an unfair advantage.

If the duel was to be on horseback, the most honorable weapons were the halberd and the lance and on foot knives, daggers, and swords. Defensive equipment could also be used such as shields or cloaks, though the sword alone was the weapon of choice. Armor was considered an honorable option as only ruffians fought without it.

If the duel was to be on horseback, the most honorable weapons were the halberd and the lance and on foot knives, daggers, and swords. Defensive equipment could also be used such as shields or cloaks, though the sword alone was the weapon of choice. Armor was considered an honorable option as only ruffians fought without it.The outcome of the duel was considered to be decreed by fortune and determined by one’s guilt or innocence. For this reason opinions differed on how the fight should be conducted. One school of thought decreed that it was acceptable for the duelist to take advantage of his opponent’s mishaps; others thought otherwise. So while it was technically permitted to stab a man fallen to the ground, to attack one recovering his lost sword, or kill a wounded man, many thought it was only chivalrous to let the opponent recover his feet before continuing the fight. If a sword was bent or broken, the judge would decide whether it could be replaced.

Unless otherwise agreed the duel would be fought to the finish, the point where either opponent died, or when one man recanted, surrendered or fled the field. If one opponent was in the power of the other and still refused to recant or surrender he could be killed, though an honorable man would spare the loser’s life. It was considered very bad form to pretend to surrender and then attack your opponent. If the fight ended in nonfatal injuries, or if both opponents died, it was up to the judge to decide the winner.

The loser might have to pay a fine, forfeit his armor to his opponent, or even become his prisoner. Although not considered a slave or servant, an imprisoned loser would have to serve his conqueror, or if released on parole, promise to come and serve him when called upon. The winner might also turn his captive over to his lord, bequeath him to his heirs or demand a ransom. Now technically without honor, the loser might never be allowed to fight another duel, or only with the permission of his conqueror.

Of course, not everyone followed the rules. If the opponents could not get their lord’s permission, or could not afford the expense of a formal duel, they might fight informally or alla macchia, in an out-of-the-way spot with no judge or rules. Unfortunately, despite their promulgation of the rules, Italians were reputed to flout those very rules with impunity, calling on cunning tricks and ruses to kill their opponents in whatever way they could, in ogni modo, maiming them or ambushing them afterwards.

In my novel The Slave, the two men in the heroine’s life resort to a duel to settle the matter once and for all.

Roberto saw that Baldassar, Batu, his second and a handful of men were already waiting for them in a patch of dappled, afternoon sunlight. Baldassar stepped forward when the Graziano party arrived, his brow creasing as he surveyed Lorenzo’s entourage of men-at-arms. The party dismounted and Lorenzo followed Baldassar to where Batu was standing, his sword resting jauntily on his shoulder, but his eyes cold.

“Right, gentlemen,” Baldassar began, “we’ll follow the usual procedures. Captain Batu has chosen arming swords. Is that acceptable, Signor de Graziano?”

Lorenzo shrugged. “If that is his preference.”

“And your seconds?”

Aldo and one of Batu’s men stepped forward, sizing each other up.

“If everything is in order, then, we begin at my signal and fight to first blood.”

“To the death.” Batu’s voice rang out.

Baldassar turned to Batu. “There’s no need for this surely…”

“To the death,” Lorenzo agreed coolly.Read more…

Short Description of The SlaveAurelia Rubbini, the only child of a rich merchant in fourteenth century Italy, has been raised to be a dutiful daughter, wife and mother, but she longs for something more than the restricted life intended for her. Then one day, her father brings home from a buying trip an Asian slave boy, Batu, who will reshape Aurelia’s destiny.

The AuthorPauline Montagna was born into an Italian family in Melbourne, Australia. After obtaining a BA in French, Italian and History, she indulged her artistic interests through amateur theater, while developing her accounting skills through a wide variety of workplaces culminating in the Australian film industry. In her mid-thirties, Pauline returned to university and qualified as a teacher of English as Second Language, a profession she pursued while completing a Diploma of Professional Writing and Editing. She has now retired from teaching to concentrate on her writing. She has published two books: The Slave, a historical romance set in medieval Italy; and Suburban Terrors, a short-story collection.

Find out more about Pauline and her books on her website. If you join her mailing list by May 31, 2014, you can get your own free e-book copy of The Slave.

ReferencesThe Duel: A History of Dueling by Robert Baldick (1965)

The Sixteenth-Century Italian Duel by Frederick R Bryson (1938)

ImagesHendrik Goltzius, A Duel on Horseback (circa 1578), from Wikimedia Commons

Hans Talhoffer, Fechtbuch (Fencing Book, 1467), from Wikimedia Commons

These pictures are in the public domain because their copyright has expired.

Published on May 09, 2014 06:30

May 2, 2014

Revisiting Varykino

I can no longer recall whether I first encountered Yuri Zhivago through David Lean’s 1965 film or Boris Pasternak’s novel. Logically, based on how I thought as a teen, I would have seen the film, fallen in love with Omar Sharif, and read the book as a result. I was in high school at the time, and Rod Steiger’s nephew (Rod Steiger plays Lara’s nemesis, Komarovsky, in the film) happened to be in my French class—a source of great prestige for him. But the timing doesn’t quite add up, since by then I also had two years of Russian under my belt, so I should have been able to follow the book better than I did. So perhaps I read the novel first, having heard how great the film was, and saw the movie only later.

I can no longer recall whether I first encountered Yuri Zhivago through David Lean’s 1965 film or Boris Pasternak’s novel. Logically, based on how I thought as a teen, I would have seen the film, fallen in love with Omar Sharif, and read the book as a result. I was in high school at the time, and Rod Steiger’s nephew (Rod Steiger plays Lara’s nemesis, Komarovsky, in the film) happened to be in my French class—a source of great prestige for him. But the timing doesn’t quite add up, since by then I also had two years of Russian under my belt, so I should have been able to follow the book better than I did. So perhaps I read the novel first, having heard how great the film was, and saw the movie only later.Either way, that was a long time ago, so when the Dead Writers Society on GoodReads decided on a group read of Doctor Zhivago in May, I volunteered to lead it. Only problem was when to fit in a 550-page book among the various novels I was reading for interviews—not to mention the temporarily neglected Reduce the TBR Challenge, for which this book counts, and my Sail to the Past History Challenge, for which it doesn’t. As group leader, I figured I needed to get my act together, so I grabbed the old Max Hayward/Manya Harari translation sitting on the bookshelf and started early. As of today, I’m two-thirds through.

So what do I see, that I missed the first time around? As with most of the books I’ve revisited after decades, the answer is “tons.” The perceptive observations on life, the skillfully delivered philosophy, the clear-eyed portrayal of revolution and civil war, the sheer gorgeousness of the writing. To pick a page at random:

The light, sunny room with its white painted walls was filled with the creamy light of the golden autumn days that follow the Feast of the Assumption, when the mornings begin to be frosty and titmice and magpies dart into the bright-leaved, thinning woods. On such days the sky is incredibly high, and through the transparent pillar of air between it and the earth there moves an icy, dark-blue radiance coming from the north. Everything in the world becomes more visible and more audible. Distant sounds reach us in a state of frozen resonance, separately and clearly. The horizons open, as if to show the whole of life for years ahead. This rarefied light would be unbearable if it were not so short-lived, coming at the end of the brief autumn day just before the early dusk.

Such was now the light in the staff room, the light of an early autumn sunset, as succulent, glassy, juicy as a certain variety of Russian apple.It’s easy to see that Pasternak was, first and foremost, a poet, even without the thirty pages of poems attributed to Zhivago at the back. And the poems themselves are exquisite, defying the occasional clunkiness introduced by translation—another feature that escaped me as a teen.

At the same time, I understand why I found the book difficult to follow in high school. I’m curious to see how the reading group will react to it. The first two chapters—a good 60 pages—are laid out like a string of beads, opening with Zhivago as a boy at his mother’s funeral and hopping across the Russian landscape from one character to another, scene by scene, each loosely connected to the one before it until the story closes the circle at the end of Chapter 2. Every character has both a three-part Russian name and at least one nickname; even I, by now accustomed to Russian naming conventions, struggled to keep them straight. Long after the central thread of the story entwines around Zhivago and Lara, then braids them together, characters mentioned only in passing continue to leap out a hundred pages on, leaving the reader with a vague sense of having encountered this person before with no recollection of when or under what circumstances. I have never wished so much for an e-book version, where I could enter the mystery character’s last name and find that earlier reference.

At the same time, I understand why I found the book difficult to follow in high school. I’m curious to see how the reading group will react to it. The first two chapters—a good 60 pages—are laid out like a string of beads, opening with Zhivago as a boy at his mother’s funeral and hopping across the Russian landscape from one character to another, scene by scene, each loosely connected to the one before it until the story closes the circle at the end of Chapter 2. Every character has both a three-part Russian name and at least one nickname; even I, by now accustomed to Russian naming conventions, struggled to keep them straight. Long after the central thread of the story entwines around Zhivago and Lara, then braids them together, characters mentioned only in passing continue to leap out a hundred pages on, leaving the reader with a vague sense of having encountered this person before with no recollection of when or under what circumstances. I have never wished so much for an e-book version, where I could enter the mystery character’s last name and find that earlier reference.Yet despite sowing a certain amount of confusion, the story hums along at a surprising clip. What I half-expected to view as a chore (however uplifting or impressive) turns out to be nothing of the sort. Knocking off 50 pages a night has not strained my capacities one bit. I’ve even read all the poems.

And in exploring those beautiful, aching verses, I have to wonder: did Pasternak write them first, as he felt his way into the novel? Or afterwards, once he knew where his characters would go? For what is more evocative of Zhivago and Lara’s hideaway than these opening stanzas from “Winter Night”?

It snowed and snowed, the whole world over,As one of the stock characters on Saturday Night Live used to say, “Discuss amongst yourselves!” Or stay tuned, as I update you on the ongoing group read.

Snow swept the world from end to end.

A candle burned on the table;

A candle burned....

The blizzard sculptured on the glass

Designs of arrows and of whorls.

A candle burned on the table;

A candle burned.

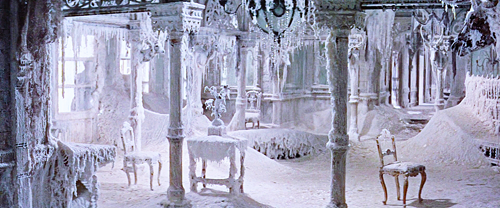

Varykino, abandoned in winter, in a screen shot from the 1965 film.

Quoted passages are from Boris Pasternak, Doctor Zhivago, trans. Max Hayward and Manya Harari, poems trans. Bernard Guilbert Guerney (New York: Pantheon Books, 1997), 185 and 542.

Published on May 02, 2014 07:00

April 25, 2014

Live-Tweeting the Exodus

Despite the title of my blog, my attempts to tackle the Internet Age have, for the most part, stalled when it comes to Twitter.

Despite the title of my blog, my attempts to tackle the Internet Age have, for the most part, stalled when it comes to Twitter. I have nothing against Twitter. I set up an account there two years ago (feel free to follow me: @cplesley), and I regularly tweet my blog posts and other news that involves my books, my friends’ books, Five Directions Press, and New Books in Historical Fiction. I follow people who look interesting, and I have a growing number of followers. I have even acquired a rudimentary understanding of hashtags and what they can do.

Yet I never felt as if I really “got” Twitter until last Saturday. There were just too many tweets to keep track of—so many that it was always like dangling a toe in a fast-flowing stream. More than a bit overwhelming. I’d heard of things trending on Twitter, but what that meant in practice—well, it passed me by.

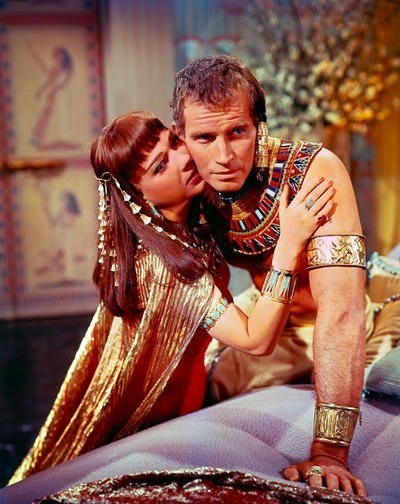

The Ten Commandments changed all that. Bear with me, please, for a brief digression. My family turned watching The Ten Commandments on TV into an annual event about ten years ago. We own the DVD, which would let us skip the commercials and shave a good 90 minutes off the show time, but we never watch the DVD. The bizarre interruptions are half the fun. I suppose the subliminal knowledge that others were watching too added to our enjoyment, but until last Saturday those others existed only as an amorphous mass: the television audience.

No matter. We didn’t need company—or so we thought. The Ten Commandments is a classic of its genre, so over the top that it screeches past serious and lands in hilarity. There are Yul Brynner’s ever-evolving miniskirts, more gloriously accessorized with every change of clothes; Edith Head, who designed the costumes, obviously told her staff to let it rip. There is the dialogue, which people in my house run around quoting (or misquoting) at random for days afterward. “So let it be written, so let it be done.” “You, Rameses, are nowhere.” “Moses, Moses, you splendid, stubborn, adorable fool!” And “You will be all mine, like my dog and my horse and my falcon. Only I will love you more, and trust you less.” Better yet, at least half the dialogue is delivered straight to the camera. The more lofty the sentiment, the more likely it is that the speaker will not look at the other participants in the conversation but instead will stare into space. We have interactions like that every day, right?

No matter. We didn’t need company—or so we thought. The Ten Commandments is a classic of its genre, so over the top that it screeches past serious and lands in hilarity. There are Yul Brynner’s ever-evolving miniskirts, more gloriously accessorized with every change of clothes; Edith Head, who designed the costumes, obviously told her staff to let it rip. There is the dialogue, which people in my house run around quoting (or misquoting) at random for days afterward. “So let it be written, so let it be done.” “You, Rameses, are nowhere.” “Moses, Moses, you splendid, stubborn, adorable fool!” And “You will be all mine, like my dog and my horse and my falcon. Only I will love you more, and trust you less.” Better yet, at least half the dialogue is delivered straight to the camera. The more lofty the sentiment, the more likely it is that the speaker will not look at the other participants in the conversation but instead will stare into space. We have interactions like that every day, right?Cue Twitter. During the first of the many, many commercial breaks, Sir Percy announced that The Ten Commandments was trending on Twitter. I checked and couldn’t see it (I told you I don’t really “get” Twitter). Sir P said, “Use the hashtag,” and I did. Sure enough, an enormous scroll of tweets flowed onto the screen. We started reading the better ones to each other—at that commercial break, and the next commercial break. By the time the movie ended, 5.5 hours later, we were barely watching the big screen; the Twitter feed was much more entertaining. Actually, we discovered midway that we were watching different feeds, because there were two hashtags, #TheTenCommandments and #TenCommandments. To cut a long story short, we eventually zeroed in on the second, which seemed to have more miniskirt and wacky-dialogue appreciators and fewer defenders of the Bible (which was not actually under attack).

So what do people say when they are live-tweeting the Exodus, as personified by Charlton Heston, Anne Baxter, and Yul Brynner? I wish I could remember all the funny tweets I saw that night. There were definitely themes: the surprising lack of naturally brown-skinned people in Egypt; the oddity of it being the chosen Easter film, embraced by a group that had forgotten it was Passover, too; parents who insisted the tweeters watch the film with them (sorry, Filial Unit!); late arrivals from the West Coast, struggling to keep up as the plot rolled relentlessly forward; objections to the length, caused by all the commercials. The rest were like us, bowled over by the bizarreness of the dialogue and the gorgeousness of the costumes.

Some of my favorites (and apologies to the tweeters for any mistakes on my part), with commentary in parentheses:

“Did he just call me lovely dust?” (Yes, Nefretiri, Moses did. Way to win over a woman, Moses!)And the winner is:

“Moses wandering off after a bush that burns. Or as they call it in Colorado, commerce!”

“The way he works that cape! Don’t make me root for you, Yul! Er … I mean Ramses.” (My thoughts precisely.)

“Blood water. You’re on notice, pharaoh. But that skirt is working with your bare chest.” (Hello. Yul must have worked out for this role.)

“Swim, horsies, swim!” (Not intended to be funny. We all feel bad for the horses. If it had been up to them, they would have let the people go.)

“Is that a bow Yul is wearing?” (Yes, indeed. A pretty white one, to contrast with his navy blue cape and silver trimming.)

“Wait, isn’t Ramses a firstborn?” (Guess not, or it would have solved a lot of problems. But the screenwriters sure kept his older siblings well hidden.)

“Moses’ mother and some random dude show up uninvited. Just like Passover at my house.”

“The Red Sea parts? Would you guys on the East Coast stop with the spoilers already?”(I assume this person was kidding, although with the state of biblical study these days one can never be quite sure.)

I can’t wait to see what they come up with next year. One more reason to watch The Ten Commandments.

Published on April 25, 2014 07:19