C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 61

October 23, 2012

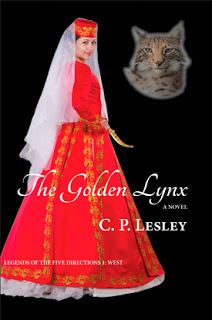

First Review of The Golden Lynx

Sorry for the delay, folks: I've been swamped with work and fell behind on my blog update this past week. So here is the latest—a short one—and Friday I'll try to get back on track with a comparison of the three paid image services I use: Clipart.com, its affiliate Photos.com, and Shutterstock.

The Golden Lynx has been selling pretty well for an indie book, but it hadn't picked up any reviews (well, not counting the one I wrote at Goodreads insistence—why does Goodreads ask you to rate your own books?!—and there I just pointed out that I was the author and therefore not a reliable reviewer) until last week, when Bryn Hammond posted this four-star review on Goodreads.

Note that Bryn (whom I don't know outside of Goodreads) is a specialist on the Mongols. You may want to check out her Of Battles Past, which is available for free on Smashwords or for 99¢ on the Kindle Store and draws heavily on The Secret History of the Mongols. I'm reading it now. So if Bryn says the book is accurate, you can be sure she knows what she's talking about.

And without more ado, here is what she said.

Bryn's Review

I had fun. I’m going to make this a very, very personal review. It may or may not be of use to others.

First off: I came because I’m into steppe history. Mind, I know next to nothing about 16thC Russian-steppe outskirts... though I always thought Russia had the most interesting history on earth; I was happy to visit.

Next: I have a thing for fighting women. When they’re from the steppe I’m a guaranteed read. The more so, as to read certain steppe fiction, you’d think these were masculinist, macho societies where women were dragged by the hair. You’d think wrong: consult the steppe epics, that our girl Nasan knows and loves. When I found fighting women from The Book of Dede Korkut, for instance, cited here as aspiration-figures, the kind of girl Nasan wants to be, I was in.

Her people are now Muslim – in the way they are in Dede Korkut, that is, with strong underlines of their earlier religion. I’ve read about the conversion to Islam hereabouts in Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tukles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition (that's a mouthful. So, I'm afraid, is the book) - where I learn, conversion is slow and never perfect. So Nasan has her 'grandmothers', whom she feels to guide her, and a spirit doll (doll to Russian eyes) that she feeds daily, treats as holy, draws inspiration from.

But I don’t mean to get abstruse here, because this novel is an adventure. It kept reminding me of old adventure tales that I loved in my youth – Robert Louis Stevenson’s New Arabian Nights, for one, where people go about the night streets in disguises. It has a strong flavour of such fare – to me – and I can’t help but suspect the author is a fan of these old adventure tales too, since her other book is a take on the Scarlet Pimpernel. It’s very plotty. You know from the blurb, the infant Ivan the Terrible is involved ... and that plot blew a breeze of Alexandre Dumas at me, too.

There's what I liked about it: the setting (with sound historical knowledge); our girl hero whose heart is on the steppe though she’s plunked into Moscow to patch up a feud with a marriage; and the adventure, that conjured up to me the old-style books, you know, in the days when they knew how to write an adventure...

The Golden Lynx has been selling pretty well for an indie book, but it hadn't picked up any reviews (well, not counting the one I wrote at Goodreads insistence—why does Goodreads ask you to rate your own books?!—and there I just pointed out that I was the author and therefore not a reliable reviewer) until last week, when Bryn Hammond posted this four-star review on Goodreads.

Note that Bryn (whom I don't know outside of Goodreads) is a specialist on the Mongols. You may want to check out her Of Battles Past, which is available for free on Smashwords or for 99¢ on the Kindle Store and draws heavily on The Secret History of the Mongols. I'm reading it now. So if Bryn says the book is accurate, you can be sure she knows what she's talking about.

And without more ado, here is what she said.

Bryn's Review

I had fun. I’m going to make this a very, very personal review. It may or may not be of use to others.

First off: I came because I’m into steppe history. Mind, I know next to nothing about 16thC Russian-steppe outskirts... though I always thought Russia had the most interesting history on earth; I was happy to visit.

Next: I have a thing for fighting women. When they’re from the steppe I’m a guaranteed read. The more so, as to read certain steppe fiction, you’d think these were masculinist, macho societies where women were dragged by the hair. You’d think wrong: consult the steppe epics, that our girl Nasan knows and loves. When I found fighting women from The Book of Dede Korkut, for instance, cited here as aspiration-figures, the kind of girl Nasan wants to be, I was in.

Her people are now Muslim – in the way they are in Dede Korkut, that is, with strong underlines of their earlier religion. I’ve read about the conversion to Islam hereabouts in Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tukles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition (that's a mouthful. So, I'm afraid, is the book) - where I learn, conversion is slow and never perfect. So Nasan has her 'grandmothers', whom she feels to guide her, and a spirit doll (doll to Russian eyes) that she feeds daily, treats as holy, draws inspiration from.

But I don’t mean to get abstruse here, because this novel is an adventure. It kept reminding me of old adventure tales that I loved in my youth – Robert Louis Stevenson’s New Arabian Nights, for one, where people go about the night streets in disguises. It has a strong flavour of such fare – to me – and I can’t help but suspect the author is a fan of these old adventure tales too, since her other book is a take on the Scarlet Pimpernel. It’s very plotty. You know from the blurb, the infant Ivan the Terrible is involved ... and that plot blew a breeze of Alexandre Dumas at me, too.

There's what I liked about it: the setting (with sound historical knowledge); our girl hero whose heart is on the steppe though she’s plunked into Moscow to patch up a feud with a marriage; and the adventure, that conjured up to me the old-style books, you know, in the days when they knew how to write an adventure...

Published on October 23, 2012 14:25

October 12, 2012

The CreateSpace Royalty Structure

Or Why I Have to Raise My Prices on The Golden Lynx

People talk about the great royalties that self-publishers get for their work. Although I am one step away from self-publishing, the small press that my writers’ group put together can survive, in part, because it takes advantage of the inexpensive printing options that the Brave New World of Publishing has made available. So in that sense, we are closer to self-publishing than to traditional publishing.

I assure you, we appreciate every option out there. Yet it’s important to be clear about what each process involves, and that includes being up front about pricing. First off, most people’s mental image of a paperback carries a price in the neighborhood of $7.99. Traditional publishers can charge those prices for mass-market paperbacks because printing is an unusual business: the big costs are in the setup. One copy costs X, but ten copies don’t cost 10X—more like 2X. Once you have set up the job on the phototypesetter, the more copies you run, the less each one costs. Print 100,000 copies, or 1,000,000, and you can make a handsome profit at $7.99, even if you are splitting it with the bookseller and handing off 10% of the wholesale price to the author (who then pays 15% to a literary agent, in mass-market publishing).

In small-press/self-publishing, the situation is different. The print-on-demand (POD) technology that makes self-publishing or small-press publishing possible relies on producing books only as they are needed. Fewer copies, no storage, no returns, lower costs. The system also relies on pre-formatted PDF files, which reduce setup costs. But as a result, there is no reduction by size of job. Each POD-published book is, in effect, a trade paperback, and these typically cost $10.99–$19.99 depending on the number of pages (production costs) of the book. In fact, Five Directions Press exists for this very reason: since we have to charge higher prices for our books, we want to ensure that readers receive a high-quality trade paperback for their money.

You would think that if a publisher can survive on charging $7.99 for a paperback while paying 8–10% to the author, then authors self-publishing at $12.99 must be raking in royalty payments by the sackful. Alas, not so—or not entirely so. The comment about great royalties applies above all to e-books. There, where production costs (although not the preparation costs) are near zero, authors routinely net 65–70% of the purchase price. Compared to 8–10% of wholesale, that’s a huge difference. I can charge $4.99 or $5.99 for an e-book and take home $3–4 in royalties. Even for four to six years’ work, that’s a good rate.

But print books do have production costs, and the royalties are calculated after the POD publisher deducts those costs. This makes perfect sense, of course: the POD publisher has to make ends meet just like everyone else. Royalties also vary by distribution channel—which is why, much as I hate to do it, I have to raise my price on The Golden Lynx as of November 1.

The math goes something like this. On The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel (300 pages), I charge $12.99 for the print edition, which nets me a royalty of about $3 per print copy (under 25%).* Although the rate is much lower, the payment approximates that of the e-book version.

If, however, I pony up (as I did, mostly as an experiment) the $25 for Expanded Distribution so that CreateSpace will list Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel with bookstores and allow wholesale purchases, I net not $3 but 70¢ on each sale (5%). I have not worried about this much lower rate, because I don’t sell many copies to bookstores (one in three months, so far). So if I sell a few books for 70¢, well, at least I’m selling books. And maybe one of those purchasers will recommend my book to friends, generating more sales.

The Golden Lynx is 50% longer than The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel: 450 pages. As a result, the production costs are proportionally higher. Even at $14.99 (which to me seems like a lot, even for a trade paperback), it nets more like $2.75 (18%) per print copy, compared to $4–$4.50 as an e-book. I consider this rate acceptable, but I didn’t sign up for Expanded Distribution because it would cost me 25¢ on every sale.

Then I realized that for Lynx, I actually need Expanded Distribution. If I want to sell to college bookstores—and I do, because I put a ton of effort into making the history accurate, and it would be wonderful if professors adopted my book for their courses—the only way to make it work is to raise my price to $16.99. I will still net only about 50¢ on every bookstore sale ($3 on print sales through Amazon.com), but if I sell enough additional copies, the difference will work itself out over time.

So on November 1, 2012, I will raise the price of the print edition of The Golden Lynx by $2 to cover the costs of Expanded Distribution (the e-book version will remain at $5.99). Until then, the book will cost $14.99.

The Brave New World of Publishing, indeed—and in many ways it is, don’t get me wrong. But perhaps not quite as lucrative as the ads would have you believe.

*Note that these are the numbers for books printed through CreateSpace and sold through Amazon.com. Books purchased directly through CreateSpace earn twice as much in royalties (because CreateSpace is not splitting its profits with Amazon.com). But since I don’t know anyone who has either bought or sold a book directly through CreateSpace, the Amazon.com numbers are the ones that matter to me. The rates for other companies (Lulu, Bookbaby, etc.) may also differ.

People talk about the great royalties that self-publishers get for their work. Although I am one step away from self-publishing, the small press that my writers’ group put together can survive, in part, because it takes advantage of the inexpensive printing options that the Brave New World of Publishing has made available. So in that sense, we are closer to self-publishing than to traditional publishing.

I assure you, we appreciate every option out there. Yet it’s important to be clear about what each process involves, and that includes being up front about pricing. First off, most people’s mental image of a paperback carries a price in the neighborhood of $7.99. Traditional publishers can charge those prices for mass-market paperbacks because printing is an unusual business: the big costs are in the setup. One copy costs X, but ten copies don’t cost 10X—more like 2X. Once you have set up the job on the phototypesetter, the more copies you run, the less each one costs. Print 100,000 copies, or 1,000,000, and you can make a handsome profit at $7.99, even if you are splitting it with the bookseller and handing off 10% of the wholesale price to the author (who then pays 15% to a literary agent, in mass-market publishing).

In small-press/self-publishing, the situation is different. The print-on-demand (POD) technology that makes self-publishing or small-press publishing possible relies on producing books only as they are needed. Fewer copies, no storage, no returns, lower costs. The system also relies on pre-formatted PDF files, which reduce setup costs. But as a result, there is no reduction by size of job. Each POD-published book is, in effect, a trade paperback, and these typically cost $10.99–$19.99 depending on the number of pages (production costs) of the book. In fact, Five Directions Press exists for this very reason: since we have to charge higher prices for our books, we want to ensure that readers receive a high-quality trade paperback for their money.

You would think that if a publisher can survive on charging $7.99 for a paperback while paying 8–10% to the author, then authors self-publishing at $12.99 must be raking in royalty payments by the sackful. Alas, not so—or not entirely so. The comment about great royalties applies above all to e-books. There, where production costs (although not the preparation costs) are near zero, authors routinely net 65–70% of the purchase price. Compared to 8–10% of wholesale, that’s a huge difference. I can charge $4.99 or $5.99 for an e-book and take home $3–4 in royalties. Even for four to six years’ work, that’s a good rate.

But print books do have production costs, and the royalties are calculated after the POD publisher deducts those costs. This makes perfect sense, of course: the POD publisher has to make ends meet just like everyone else. Royalties also vary by distribution channel—which is why, much as I hate to do it, I have to raise my price on The Golden Lynx as of November 1.

The math goes something like this. On The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel (300 pages), I charge $12.99 for the print edition, which nets me a royalty of about $3 per print copy (under 25%).* Although the rate is much lower, the payment approximates that of the e-book version.

If, however, I pony up (as I did, mostly as an experiment) the $25 for Expanded Distribution so that CreateSpace will list Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel with bookstores and allow wholesale purchases, I net not $3 but 70¢ on each sale (5%). I have not worried about this much lower rate, because I don’t sell many copies to bookstores (one in three months, so far). So if I sell a few books for 70¢, well, at least I’m selling books. And maybe one of those purchasers will recommend my book to friends, generating more sales.

The Golden Lynx is 50% longer than The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel: 450 pages. As a result, the production costs are proportionally higher. Even at $14.99 (which to me seems like a lot, even for a trade paperback), it nets more like $2.75 (18%) per print copy, compared to $4–$4.50 as an e-book. I consider this rate acceptable, but I didn’t sign up for Expanded Distribution because it would cost me 25¢ on every sale.

Then I realized that for Lynx, I actually need Expanded Distribution. If I want to sell to college bookstores—and I do, because I put a ton of effort into making the history accurate, and it would be wonderful if professors adopted my book for their courses—the only way to make it work is to raise my price to $16.99. I will still net only about 50¢ on every bookstore sale ($3 on print sales through Amazon.com), but if I sell enough additional copies, the difference will work itself out over time.

So on November 1, 2012, I will raise the price of the print edition of The Golden Lynx by $2 to cover the costs of Expanded Distribution (the e-book version will remain at $5.99). Until then, the book will cost $14.99.

The Brave New World of Publishing, indeed—and in many ways it is, don’t get me wrong. But perhaps not quite as lucrative as the ads would have you believe.

*Note that these are the numbers for books printed through CreateSpace and sold through Amazon.com. Books purchased directly through CreateSpace earn twice as much in royalties (because CreateSpace is not splitting its profits with Amazon.com). But since I don’t know anyone who has either bought or sold a book directly through CreateSpace, the Amazon.com numbers are the ones that matter to me. The rates for other companies (Lulu, Bookbaby, etc.) may also differ.

Published on October 12, 2012 18:01

October 5, 2012

Recreating a Nomadic Tent (Fun with History, Part 2)

As I mentioned in "The Art of the Borgias" (http://blog.cplesley.com/2012/07/the-art-of-borgias-fun-with-history.html), I love historical research, even in the frequent cases where the books don't tell me what a historical novelist needs to know. But for the last month at least, I have been tearing my hair out trying to decide what my hero would experience when he returns to the nomadic camp where he spent his childhood.

Thanks to the Internet and some wonderful books I purchased secondhand—most notably, Alma Kunanbay's The Soul of Kazakhstan (with its amazingly beautiful photographs by Wayne Eastep)—I have a good idea of what a Tatar nomadic camp looked like. I can guess what it sounded like: a small group of people in an isolated prairie, surrounded by huge herds of sheep, goats, and horses and intermittently mobilized for war. But what did it smell like? How did the leaders differentiate their tents from the common people's? What distinguished a man's tent from a woman's? When you have to pack everything on a wagon and move it four or more times a year, every belonging must be both essential and deeply valued; otherwise it gets left behind. But how does that knowledge play out in terms of the internal arrangements of a bey's tent? What was essential? What did people value so much that it became essential to them, if not to everyone?

Moreover, my hero left his childhood camp six years ago. In the meantime he has visited and lived in cities: Astrakhan, at the mouth of the Volga, tied into the Persian and Indian trade routes; Kazan, far to Astrakhan's north but still on the Volga, a flourishing commercial city connecting the Siberian hinterland to lands west and south; Moscow, then the emerging capital of a rapidly expanding Russia; Smolensk, on Russia's route to Poland and everything west of Poland. Even Kasimov, the small town where my hero Ogodai has spent the last two years, would have had amenities the nomads could only dream of—books, piped heat in winter, perhaps even internal plumbing systems. He has matured and become cosmopolitan, so things that once seemed normal or even desirable to him may look quite different now. Other things he didn't notice at twelve will stand out, for better or worse.

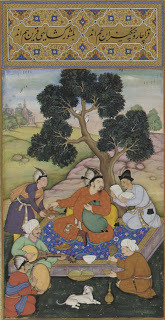

I have found snippets of information here and there. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor (founder of the Indian Mughal dynasty) mentions a visit paid by Babur to his nomadic uncle. I had great hopes of this account, but alas, Babur mentions only that his uncle kept his tent in the old style, with horse tackle piled around the edges and melon rinds scattered on the dirt floor. Indicative, but worth about a sentence and a half even if stolen (and I am not above stealing any useful detail). In another source, I discovered that the steppe nomads used dried animal dung for fuel, which must get pretty pungent as it burns. Milk is also a big part of steppe culture: sour milk, fresh milk, milk spattered to feed ancestors or tossed after departing guests. And meat, which with milk products constitutes a steppe nomad's main food. Butchered meat, cooked meat, tanned skins—you get the picture. Most likely, my hero would not focus on those smells, as his customs would be the same, but he might notice them in passing.

Then I remembered, although I have yet to pinpoint where I read it, that the Mongols traditionally avoided bathing in rivers and streams, which polluted the water and angered the spirits who dwelled there. Nor did they wash their clothes. With water scarce on the steppe, I can imagine that modern standards of hygiene may not have prevailed there, either. By the time of my story, those of the Mongols' descendants who became Tatars had adopted Islam. As a result, they were, on the whole, cleaner in the early modern period than their non-Muslim neighbors (Muslims wash five times a day before praying and bathe their entire bodies after various routine activities). But in the 1530s the nomadic Tatars I am describing were at best nominal Muslims. A visitor accustomed to more stringent application of the purification requirements would certainly notice and deplore near-universal body odor and filthy clothes. And in places where something as basic as water or food is scarce, the elite tend to monopolize it, so that might also mark differences in social status. Not much to go on, but a start.

I am plowing on, trying to create a plausible setting out of these few specks of information. Nonetheless, this is one occasion when I would love to have access to a time machine. Zip in, sniff the air, take notes, zip out. It would make life so much easier.

H.G. Wells, where are you?

A Nomadic Tent, Photographed in Color by Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky circa 1915

Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

This photograph shows the tent as it would appear in the summer, without the familiar felt coverings, which provide insulation and warmth.

Thanks to the Internet and some wonderful books I purchased secondhand—most notably, Alma Kunanbay's The Soul of Kazakhstan (with its amazingly beautiful photographs by Wayne Eastep)—I have a good idea of what a Tatar nomadic camp looked like. I can guess what it sounded like: a small group of people in an isolated prairie, surrounded by huge herds of sheep, goats, and horses and intermittently mobilized for war. But what did it smell like? How did the leaders differentiate their tents from the common people's? What distinguished a man's tent from a woman's? When you have to pack everything on a wagon and move it four or more times a year, every belonging must be both essential and deeply valued; otherwise it gets left behind. But how does that knowledge play out in terms of the internal arrangements of a bey's tent? What was essential? What did people value so much that it became essential to them, if not to everyone?

Moreover, my hero left his childhood camp six years ago. In the meantime he has visited and lived in cities: Astrakhan, at the mouth of the Volga, tied into the Persian and Indian trade routes; Kazan, far to Astrakhan's north but still on the Volga, a flourishing commercial city connecting the Siberian hinterland to lands west and south; Moscow, then the emerging capital of a rapidly expanding Russia; Smolensk, on Russia's route to Poland and everything west of Poland. Even Kasimov, the small town where my hero Ogodai has spent the last two years, would have had amenities the nomads could only dream of—books, piped heat in winter, perhaps even internal plumbing systems. He has matured and become cosmopolitan, so things that once seemed normal or even desirable to him may look quite different now. Other things he didn't notice at twelve will stand out, for better or worse.

I have found snippets of information here and there. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor (founder of the Indian Mughal dynasty) mentions a visit paid by Babur to his nomadic uncle. I had great hopes of this account, but alas, Babur mentions only that his uncle kept his tent in the old style, with horse tackle piled around the edges and melon rinds scattered on the dirt floor. Indicative, but worth about a sentence and a half even if stolen (and I am not above stealing any useful detail). In another source, I discovered that the steppe nomads used dried animal dung for fuel, which must get pretty pungent as it burns. Milk is also a big part of steppe culture: sour milk, fresh milk, milk spattered to feed ancestors or tossed after departing guests. And meat, which with milk products constitutes a steppe nomad's main food. Butchered meat, cooked meat, tanned skins—you get the picture. Most likely, my hero would not focus on those smells, as his customs would be the same, but he might notice them in passing.

Then I remembered, although I have yet to pinpoint where I read it, that the Mongols traditionally avoided bathing in rivers and streams, which polluted the water and angered the spirits who dwelled there. Nor did they wash their clothes. With water scarce on the steppe, I can imagine that modern standards of hygiene may not have prevailed there, either. By the time of my story, those of the Mongols' descendants who became Tatars had adopted Islam. As a result, they were, on the whole, cleaner in the early modern period than their non-Muslim neighbors (Muslims wash five times a day before praying and bathe their entire bodies after various routine activities). But in the 1530s the nomadic Tatars I am describing were at best nominal Muslims. A visitor accustomed to more stringent application of the purification requirements would certainly notice and deplore near-universal body odor and filthy clothes. And in places where something as basic as water or food is scarce, the elite tend to monopolize it, so that might also mark differences in social status. Not much to go on, but a start.

I am plowing on, trying to create a plausible setting out of these few specks of information. Nonetheless, this is one occasion when I would love to have access to a time machine. Zip in, sniff the air, take notes, zip out. It would make life so much easier.

H.G. Wells, where are you?

A Nomadic Tent, Photographed in Color by Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky circa 1915

Courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

This photograph shows the tent as it would appear in the summer, without the familiar felt coverings, which provide insulation and warmth.

Published on October 05, 2012 13:26

September 28, 2012

Liebster Blog Award

Last Saturday I was both surprised and delighted to receive the Liebster Blog Award. Pathetic as it sounds, I was not even aware of blog awards until this one came my way, and now I’m happy to pass along the good karma to other hard-working, under-appreciated folk. It took me a few days to find the right mix, because so many good candidates had already been nominated. But I finally came up with a list. (For my nominations, see the end of the post.)

The Rules The Liebster Blog Award is supposed to be given to smaller, deserving blogs with 300 or less followers in hopes of sharing that blogger’s hard work with the rest of the world. You are supposed to thank the person who nominated you as well as nominate 3 to 5 blogs yourself. Finally, you can answer some questions about yourself that your nominator either came up for you or used in their own acceptance blog. I have borrowed some of my nominator’s questions.

So, to get started, thank you, Pixie Bubbles, for nominating me! This is my first blog award, and I am so happy to receive it, especially from someone I had not known previously. Not only do I appreciate the award, but I am happy to have discovered your blog, http://lifewithchocolateandcoffee.wordpress.com, which I will be following from now on.

Questions and Answers

What keeps you writing when you have writer’s block? I hardly ever have writer’s block, strictly speaking (writer’s procrastination is another story). When I do, I stop and think about my novel and what's wrong with it—what’s tripping me up, in other words. Usually, I’m trying to force a character. Sometimes I’m not really immersing myself in the scene, so the writing feels clichéd and flat. If I can identify what the problem is, then I’m energized to go on. If not, I go back and edit a previous section. That almost always gets me back in the flow.

Most writers have a literary counterpart—a character from their stories who reflects themselves. Tell us about yours.Nina Pennington from The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, my first novel, is the most like me: a historian, better with books than with people, socially awkward, serious, a bit literal minded. I’m not shy now, but I used to be when I was younger. And Nina was more like me in earlier drafts, but I learned from writing Nasan (in The Golden Lynx—my second book, just published) that it’s easier to write someone who’s less like me.

What are your passions? Writing, reading, taking classical ballet classes. Cats—I have two, and they’'re great. I also have an odd weakness for new software programs.

You’ve had a fight with your significant other and you want to fix things. I do the opposite of what my characters do! I try to listen to my husband’s point of view—not immediately, while I’m still angry, but as soon as I can—and try to keep talking until I can imagine what the problem looks like to him. And apologize, even if I think he’s exaggerating. There’s almost always something to apologize for, and it helps get past the emotional barriers of both people trying to prove they're right.

What’s one injustice you see in the world that you would fix in a story?Most of the injustice in the world comes from one group of people judging others on the basis of superficial characteristics. Even when my characters start out doing that (and most of them do, in one way or another), all my stories encourage people to see past those outward differences and recognize others’ humanity. Characters who make that leap succeed; those who don’t, fail.

If you could change one thing in your life, what would it be?I would have started writing fiction earlier, so that I could have learned more and established professional ties sooner. And I would like to write full-time, or at least half-time, from now on. I can’t afford to do that yet, but I would love to one day.

What’s important to you at this point in time?Finishing the series I’ve started and finding a way to have more free time to do the things I love, including spending time with my family.

Do you make it a habit of telling others what you thought of their work, even if your experience wasn’t good?I never offer critiques unasked. If people do ask me, then I tell them the truth, but the truth includes the good as well as the bad. So I start by looking for what I liked in their work, then I offer positive, specific suggestions for how to fix the problems. For example, I would say, “I don’'t understand why this character reacts this way to this event” or “If someone treated me this way, I would want to kick him,” not “this character makes no sense” or “I hated this section.” Even if it’s true, it’s not helpful. The person won’t hear what the problem is or know how to fix it. And in most cases, it is not true. More often, a vague response expresses laziness or frustration on the part of the critiquer, who didn’t take the time to figure out exactly what s/he was reacting to.

Nominations

Last, here are my nominations. I will notify each winner personally. As Pixie Bubbles noted when she nominated me, I selected these people because they seemed to have put time and effort into creating interesting, thoughtful blogs that deserve to be better known. Some of them I know, others I don’t, but quality, not friendship, was the deciding factor. I also tried to pick sites that had not already received awards. So check them out. You should find something you like!

Here are the five people I nominate:

Karen Adams: http://illiterationnation.blogspot.com

Julian Berengaut: http://www.wormwood-and-honey.com

Stephanie Carroll: http://unhingedhistorian.blogspot.com

Courtney J. Hall: http://courtneyjhall.com

Sandi Sonnenfeld: http://www.sandisonnenfeld.com/blog.htm

And so that the winners do not need to ask (as I did), being nominated is the same as winning. So start investigating the blogs you yourself would like to nominate!

P. S. Karen Adams writes to me that she can’t participate at this time, so I would like to nominate in her place Bryn Hammond’s blog: http://amgalant.com. I just discovered Bryn’s blog last night, after making my choices and writing this post. While I think it will interest many people, it has a special meaning for me. My Legends of the Five Directions series explores the lives and culture of Genghis (more properly, Chinggis, Jinggis, or Jenghis—that g is soft) Khan’s descendants, so it deals with similar topics at a different time.

The Rules The Liebster Blog Award is supposed to be given to smaller, deserving blogs with 300 or less followers in hopes of sharing that blogger’s hard work with the rest of the world. You are supposed to thank the person who nominated you as well as nominate 3 to 5 blogs yourself. Finally, you can answer some questions about yourself that your nominator either came up for you or used in their own acceptance blog. I have borrowed some of my nominator’s questions.

So, to get started, thank you, Pixie Bubbles, for nominating me! This is my first blog award, and I am so happy to receive it, especially from someone I had not known previously. Not only do I appreciate the award, but I am happy to have discovered your blog, http://lifewithchocolateandcoffee.wordpress.com, which I will be following from now on.

Questions and Answers

What keeps you writing when you have writer’s block? I hardly ever have writer’s block, strictly speaking (writer’s procrastination is another story). When I do, I stop and think about my novel and what's wrong with it—what’s tripping me up, in other words. Usually, I’m trying to force a character. Sometimes I’m not really immersing myself in the scene, so the writing feels clichéd and flat. If I can identify what the problem is, then I’m energized to go on. If not, I go back and edit a previous section. That almost always gets me back in the flow.

Most writers have a literary counterpart—a character from their stories who reflects themselves. Tell us about yours.Nina Pennington from The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, my first novel, is the most like me: a historian, better with books than with people, socially awkward, serious, a bit literal minded. I’m not shy now, but I used to be when I was younger. And Nina was more like me in earlier drafts, but I learned from writing Nasan (in The Golden Lynx—my second book, just published) that it’s easier to write someone who’s less like me.

What are your passions? Writing, reading, taking classical ballet classes. Cats—I have two, and they’'re great. I also have an odd weakness for new software programs.

You’ve had a fight with your significant other and you want to fix things. I do the opposite of what my characters do! I try to listen to my husband’s point of view—not immediately, while I’m still angry, but as soon as I can—and try to keep talking until I can imagine what the problem looks like to him. And apologize, even if I think he’s exaggerating. There’s almost always something to apologize for, and it helps get past the emotional barriers of both people trying to prove they're right.

What’s one injustice you see in the world that you would fix in a story?Most of the injustice in the world comes from one group of people judging others on the basis of superficial characteristics. Even when my characters start out doing that (and most of them do, in one way or another), all my stories encourage people to see past those outward differences and recognize others’ humanity. Characters who make that leap succeed; those who don’t, fail.

If you could change one thing in your life, what would it be?I would have started writing fiction earlier, so that I could have learned more and established professional ties sooner. And I would like to write full-time, or at least half-time, from now on. I can’t afford to do that yet, but I would love to one day.

What’s important to you at this point in time?Finishing the series I’ve started and finding a way to have more free time to do the things I love, including spending time with my family.

Do you make it a habit of telling others what you thought of their work, even if your experience wasn’t good?I never offer critiques unasked. If people do ask me, then I tell them the truth, but the truth includes the good as well as the bad. So I start by looking for what I liked in their work, then I offer positive, specific suggestions for how to fix the problems. For example, I would say, “I don’'t understand why this character reacts this way to this event” or “If someone treated me this way, I would want to kick him,” not “this character makes no sense” or “I hated this section.” Even if it’s true, it’s not helpful. The person won’t hear what the problem is or know how to fix it. And in most cases, it is not true. More often, a vague response expresses laziness or frustration on the part of the critiquer, who didn’t take the time to figure out exactly what s/he was reacting to.

Nominations

Last, here are my nominations. I will notify each winner personally. As Pixie Bubbles noted when she nominated me, I selected these people because they seemed to have put time and effort into creating interesting, thoughtful blogs that deserve to be better known. Some of them I know, others I don’t, but quality, not friendship, was the deciding factor. I also tried to pick sites that had not already received awards. So check them out. You should find something you like!

Here are the five people I nominate:

Karen Adams: http://illiterationnation.blogspot.com

Julian Berengaut: http://www.wormwood-and-honey.com

Stephanie Carroll: http://unhingedhistorian.blogspot.com

Courtney J. Hall: http://courtneyjhall.com

Sandi Sonnenfeld: http://www.sandisonnenfeld.com/blog.htm

And so that the winners do not need to ask (as I did), being nominated is the same as winning. So start investigating the blogs you yourself would like to nominate!

P. S. Karen Adams writes to me that she can’t participate at this time, so I would like to nominate in her place Bryn Hammond’s blog: http://amgalant.com. I just discovered Bryn’s blog last night, after making my choices and writing this post. While I think it will interest many people, it has a special meaning for me. My Legends of the Five Directions series explores the lives and culture of Genghis (more properly, Chinggis, Jinggis, or Jenghis—that g is soft) Khan’s descendants, so it deals with similar topics at a different time.

Published on September 28, 2012 16:59

September 22, 2012

Does It Really Cost Nothing to Produce an e-Book?

The Rationale behind Five Directions Press

This is not a new question, but it resurfaced for me with a recent post I saw on Goodreads. Someone was objecting to paying $20 for an e-book because, to paraphrase, e-books cost nothing to produce.

Well, I too object to paying $20 for an e-book. In fact, I object to paying $20-25 for any book, even a hardcover or a nonfiction book. In the days before e-readers, I routinely borrowed hardbacks from the local public library or waited a year for the paperback release rather than shell out full price. For an e-book, which requires no paper and no physical storage, existing solely as a tiny bunch of electronic data on huge servers that would be running anyway to meet the world’s computing needs, $20 indeed seems excessive.

But does it follow that because electronic books cost negligible sums to store and to read and nothing to print, there are therefore no costs associated with e-publication? That e-books should be free or $0.99 or some other negligible sum? That proposition is much more difficult to sustain.

In their defense of high prices, traditional publishers note that they maintain staffs of editors, cover and book designers, compositors, art directors, marketers, and more. They pay rent and upkeep on buildings, furniture, and equipment. They pay taxes. They run advertising campaigns to promote their titles. They hire freelance copy editors and proofreaders to ensure that the books they produce correspond to house style and go to press as free of spelling, typographical, and other errors as is humanly possible. These people are meticulous and often extremely talented. Their expertise is the reason that print books produced by traditional publishers look professional—and their absence explains why self-published books often, regrettably, don’t. But they cost money. Lots of money, even if you don’t pay them full salaries and benefits but just hire one as you need him or her for a specific job. Those costs are reflected in the e-book price, just as they are reflected in the print price. There are additional expenses for printing and storing and distributing physical books, but they are much smaller than you might think.

Of course, self-pubbed authors and small presses don’t bear all those costs. Their offices exist within their homes; they write their books on their own computers using software they already own or dedicated novel-writing programs that sell for $30–$60. Unless they hit it big, their royalties are folded into their taxes. ISBNs cost little or nothing; CreateSpace, Kindle Direct Publishing, PubIt, Apple, and Smashwords do not charge for uploading or storing finished files. They do take a portion of the sales, but compared to the amount retained by traditional publishers and literary agencies, these fees are low—especially for e-books, where the author can easily pocket 60–70%. In that sense, you could argue that a self-pubbed e-book costs nothing to produce, and a print book costs $5-10, depending on length, trim size, color vs. black and white, and certain other factors. (These prices refer to print-on-demand publishing; the math for traditional publishing differs.) If the author is willing to discount the time s/he spent in writing the book, formatting the file, and plugging the e-book to everyone s/he knows, then a person could claim that a self-pubbed e-book should sell for author royalty plus whatever the platform charges, and a self-pubbed print version should sell for that sum plus the actual production costs (the $5-10).

But that argument also assumes that the author can manage all the different tasks required to produce a result professional enough to attract a reader accustomed to the beauty and elegance of traditionally published books. As soon as the author falls down on one of the tasks—editor, book designer, art director, cover designer, publicist, advertising specialist—and has to hire help, the math breaks down. A good copy editor charges $3-$10 for a 250-word page, which works out to $1,200-$4,000 for a typical 100,000-word novel. Graphic designers, publicists, and techies who can figure out the intricacies of HTML, MOBI, and ePub have their own pricing schedules. To get a sense of the high end of potential costs for self-publishing, see this article from Poets and Writers Magazine. Either the author recoups those costs through the purchase price, or the author absorbs them: there is no other choice.

So what is an author bent on self-publishing to do?

What my writers’ group decided to do was to establish Five Directions Press. We bill ourselves as a writers’ cooperative, because no money changes hands. Instead, we pool resources. One of us has experience editing and typesetting (and has been funneling a portion of her paycheck into Adobe software since Adobe came out with PageMaker 6.0). Another is a graphic designer; a third worked with art museums and supervised card design for an international agency; a fourth had a career in advertising before she began writing fiction. We’re hoping to add another editor over the next year.

Because we don’t charge one another for our services, we can’t operate according to an open-business model and accept outside clients. That’s why our website lists us as closed to submissions. But we do charge for our books, including our e-books. Not $20, but not $0.99 either. Because the amount of time that goes into editing, designing, typesetting, proofing, creating appropriate covers and ads, maintaining and updating the website, and developing promotional campaigns runs into hundreds of hours per title that we could devote to writing—and that doesn’t even count the years of effort that went into creating and critiquing and revising each book before it ever reached that stage. The payoff, we hope, will be high-quality books that people will want to buy.

That solution won’t work for everyone, of course. We were lucky in that we happened to have a unique blend of skills associated with publishing. Even so, it’s an idea worth considering. As the recent launching of the WANA Commons group on Flickr shows, creative people often have artistic skills in more than one area, and if you ask around, you may find other writers willing to barter graphic design for advertising or proofreading for a good character critique. Which brings me back to my original question.

Do e-books really cost nothing to produce? No. Behind the scenes, vast amounts of effort go into publishing even the simplest e-book. Into any book, by any author who devotes months, if not years, to developing a story and studying the craft and making the effort to imagine multidimensional characters that s/he can shove into conflict-ridden settings and force to grow. Worlds take time to create, much longer to nurture. And as my first boss once told me, “time is also money.”

Come to think of it, maybe $20 isn’t so out of line after all.

(Joke: Five Directions Press will not be charging $20 for its print or its e-book editions anytime soon.)

This is not a new question, but it resurfaced for me with a recent post I saw on Goodreads. Someone was objecting to paying $20 for an e-book because, to paraphrase, e-books cost nothing to produce.

Well, I too object to paying $20 for an e-book. In fact, I object to paying $20-25 for any book, even a hardcover or a nonfiction book. In the days before e-readers, I routinely borrowed hardbacks from the local public library or waited a year for the paperback release rather than shell out full price. For an e-book, which requires no paper and no physical storage, existing solely as a tiny bunch of electronic data on huge servers that would be running anyway to meet the world’s computing needs, $20 indeed seems excessive.

But does it follow that because electronic books cost negligible sums to store and to read and nothing to print, there are therefore no costs associated with e-publication? That e-books should be free or $0.99 or some other negligible sum? That proposition is much more difficult to sustain.

In their defense of high prices, traditional publishers note that they maintain staffs of editors, cover and book designers, compositors, art directors, marketers, and more. They pay rent and upkeep on buildings, furniture, and equipment. They pay taxes. They run advertising campaigns to promote their titles. They hire freelance copy editors and proofreaders to ensure that the books they produce correspond to house style and go to press as free of spelling, typographical, and other errors as is humanly possible. These people are meticulous and often extremely talented. Their expertise is the reason that print books produced by traditional publishers look professional—and their absence explains why self-published books often, regrettably, don’t. But they cost money. Lots of money, even if you don’t pay them full salaries and benefits but just hire one as you need him or her for a specific job. Those costs are reflected in the e-book price, just as they are reflected in the print price. There are additional expenses for printing and storing and distributing physical books, but they are much smaller than you might think.

Of course, self-pubbed authors and small presses don’t bear all those costs. Their offices exist within their homes; they write their books on their own computers using software they already own or dedicated novel-writing programs that sell for $30–$60. Unless they hit it big, their royalties are folded into their taxes. ISBNs cost little or nothing; CreateSpace, Kindle Direct Publishing, PubIt, Apple, and Smashwords do not charge for uploading or storing finished files. They do take a portion of the sales, but compared to the amount retained by traditional publishers and literary agencies, these fees are low—especially for e-books, where the author can easily pocket 60–70%. In that sense, you could argue that a self-pubbed e-book costs nothing to produce, and a print book costs $5-10, depending on length, trim size, color vs. black and white, and certain other factors. (These prices refer to print-on-demand publishing; the math for traditional publishing differs.) If the author is willing to discount the time s/he spent in writing the book, formatting the file, and plugging the e-book to everyone s/he knows, then a person could claim that a self-pubbed e-book should sell for author royalty plus whatever the platform charges, and a self-pubbed print version should sell for that sum plus the actual production costs (the $5-10).

But that argument also assumes that the author can manage all the different tasks required to produce a result professional enough to attract a reader accustomed to the beauty and elegance of traditionally published books. As soon as the author falls down on one of the tasks—editor, book designer, art director, cover designer, publicist, advertising specialist—and has to hire help, the math breaks down. A good copy editor charges $3-$10 for a 250-word page, which works out to $1,200-$4,000 for a typical 100,000-word novel. Graphic designers, publicists, and techies who can figure out the intricacies of HTML, MOBI, and ePub have their own pricing schedules. To get a sense of the high end of potential costs for self-publishing, see this article from Poets and Writers Magazine. Either the author recoups those costs through the purchase price, or the author absorbs them: there is no other choice.

So what is an author bent on self-publishing to do?

What my writers’ group decided to do was to establish Five Directions Press. We bill ourselves as a writers’ cooperative, because no money changes hands. Instead, we pool resources. One of us has experience editing and typesetting (and has been funneling a portion of her paycheck into Adobe software since Adobe came out with PageMaker 6.0). Another is a graphic designer; a third worked with art museums and supervised card design for an international agency; a fourth had a career in advertising before she began writing fiction. We’re hoping to add another editor over the next year.

Because we don’t charge one another for our services, we can’t operate according to an open-business model and accept outside clients. That’s why our website lists us as closed to submissions. But we do charge for our books, including our e-books. Not $20, but not $0.99 either. Because the amount of time that goes into editing, designing, typesetting, proofing, creating appropriate covers and ads, maintaining and updating the website, and developing promotional campaigns runs into hundreds of hours per title that we could devote to writing—and that doesn’t even count the years of effort that went into creating and critiquing and revising each book before it ever reached that stage. The payoff, we hope, will be high-quality books that people will want to buy.

That solution won’t work for everyone, of course. We were lucky in that we happened to have a unique blend of skills associated with publishing. Even so, it’s an idea worth considering. As the recent launching of the WANA Commons group on Flickr shows, creative people often have artistic skills in more than one area, and if you ask around, you may find other writers willing to barter graphic design for advertising or proofreading for a good character critique. Which brings me back to my original question.

Do e-books really cost nothing to produce? No. Behind the scenes, vast amounts of effort go into publishing even the simplest e-book. Into any book, by any author who devotes months, if not years, to developing a story and studying the craft and making the effort to imagine multidimensional characters that s/he can shove into conflict-ridden settings and force to grow. Worlds take time to create, much longer to nurture. And as my first boss once told me, “time is also money.”

Come to think of it, maybe $20 isn’t so out of line after all.

(Joke: Five Directions Press will not be charging $20 for its print or its e-book editions anytime soon.)

Published on September 22, 2012 13:14

September 16, 2012

On the Prowl: The Golden Lynx

For those of you who have been following my blog posts, this won’t come as a huge surprise. Nonetheless, I’m happy to announce that I have crossed the publishing Rubicon and my new novel, The Golden Lynx, is now available for everyone to read. You’ll find the links to the print, ePub, and Kindle editions on my blog (somehow the formatting became garbled when Goodreads read in the post). And for those who skipped my post on "The Art of the Blurb," a capsule description of the book follows.

Here's your chance to learn about a fascinating period in a faraway world without studying!

Description

WHO IS THE GOLDEN LYNX?

Russia, 1534. Elite clans battle for control of the toddler who will become their first tsar, Ivan the Terrible. Amid the chaos and upheaval, a masked man mysteriously appears night after night to aid the desperate people.

Or is he a man?

Sixteen-year-old Nasan Kolychev is trapped in a loveless marriage. To escape her misery, she dons boys' clothes and slips away under cover of night to help those in need. She never intends to do more than assist a few souls and give her life purpose. But before long, Nasan finds herself caught up in events that will decide the future of Russia.

And so, a girl who has become the greatest hero of her time must decide whether to save a baby destined to become the greatest villain of his.

Here's your chance to learn about a fascinating period in a faraway world without studying!

Description

WHO IS THE GOLDEN LYNX?

Russia, 1534. Elite clans battle for control of the toddler who will become their first tsar, Ivan the Terrible. Amid the chaos and upheaval, a masked man mysteriously appears night after night to aid the desperate people.

Or is he a man?

Sixteen-year-old Nasan Kolychev is trapped in a loveless marriage. To escape her misery, she dons boys' clothes and slips away under cover of night to help those in need. She never intends to do more than assist a few souls and give her life purpose. But before long, Nasan finds herself caught up in events that will decide the future of Russia.

And so, a girl who has become the greatest hero of her time must decide whether to save a baby destined to become the greatest villain of his.

Published on September 16, 2012 08:31

September 7, 2012

The Great Cover Hunt Continued

So far, most of my discussion of covers has involved copyright and my attempts to avoid violation thereof. But what about creating the cover itself? If you’re a self- or indie-published author, cover creation probably doesn’t rank high on your list of marketable skills. I have a career in editing and typesetting, coupled with a jill-of-all-trades’ need to perform occasional feats of design, but I still wouldn’t consider myself rich in the kind of experience needed to create a professional-quality book cover. Yet here I am, with three under my belt, two more planned, and another four sketched out. I certainly don’t claim expertise, but in the interests of sparking discussion, I thought I would share some of the story behind the covers I created for my two novels—one already in print, the other due to release for sale as soon as I approve the print proofs (expect an update when I see what that cover looks like once attached to an actual book).

With The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, I had a design in my head from the beginning. It took me a while to get it right, but even in its earliest formulation (the one now roaming the Web as a pirated graphic), the red velvet and the 18th-century sword figured prominently. Adding, then doubling (to represent either the dual nature of Ian/Percy or the heroine’s equality with the hero—take your pick), the scarlet pimpernel; finding the right sword and velvet; then making sure I wasn’t stealing anyone’s image—all these details took time. But the basic idea was already in place.

Not so with The Golden Lynx. The story contains three lynxes, for starters: a spirit animal who takes the form of an actual lynx, a gold necklace in the form of Scythian jewelry given to the heroine at a crucial moment by her older brother, and the heroine herself, who takes refuge from her troubles by becoming a female Scarlet Pimpernel whom the locals dub the Golden Lynx. I was so excited the day I discovered that Eurasian lynxes really are golden brown. And when I found the perfect circle (a Scythian panther) to represent the gold necklace.

My early versions of the cover featured all three: lynx front and center, girl shadowy in the background, jewelry next to her. Unfortunately, in my early period of ignorance, I failed to consider the copyright status of my first set of images. The lynx turned out to be the work of a Czech photographer. The girl came from a video published on Youtube by the Republic of Tatarstan. Public domain? No way to tell—I swear I looked, but there was no information even about the person who uploaded the video. The jewelry belongs to the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, which does allow people to download its images, although not for commercial use. And the Hermitage site does not include that particular image, which now no longer shows up in Google Images at all.

So in the best case, I would have had to find alternatives. A bigger problem, though, was the design itself. As my invaluable critique group pointed out, the actual lynx took over the cover. In the end, the story is about a girl, not a wildcat. The cover did not make this clear.

I shifted the elements around to emphasize the heroine and relegate her spirit guide to the background, then began trawling Shutterstock for images of girls around my heroine’s age. This one had the right attitude, although nothing about her screams “16th-century Turkic princess.”

I shifted the elements around to emphasize the heroine and relegate her spirit guide to the background, then began trawling Shutterstock for images of girls around my heroine’s age. This one had the right attitude, although nothing about her screams “16th-century Turkic princess.”

This one at least sports a costume plausible for my heroine masquerading as the Golden Lynx. But the girl’s demeanor, if culturally correct, seems rather demure for a tomboy defying every social convention because she’s mad at her new husband.

This one at least sports a costume plausible for my heroine masquerading as the Golden Lynx. But the girl’s demeanor, if culturally correct, seems rather demure for a tomboy defying every social convention because she’s mad at her new husband.

Finally, I wised up and ran a search on Shutterstock for “Tatar bride.” Bingo. Rather surprisingly, even if we exclude the pictures of raw beef and sauce for fish, Shutterstock carries a remarkable number of photographs of actual Tatars.

With the addition of an Ottoman dagger, also from Shutterstock, and a beautiful Eurasian lynx courtesy of Bernard Landgraf (reused under a Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike 3.0 Unported license), I came up with the cover below. Perhaps a bit spare, but everything I tried adding made the result look cluttered. So in the end I left it as is. The black background will carry over nicely into the other books in this series, becoming a unifying theme. And the elements catch the eye even when reduced to thumbnail size, not an unimportant consideration in this day and age.

And please note, that although the manipulated lynx can be reused under the same terms (attribution/share-alike) as the original, the other images in this post were purchased from Shutterstock, so using them without buying your own license violates that company’s copyright.

For up-to-date publication information on The Golden Lynx, see http://www.fivedirectionspress.com.

For the story of the back cover, see my previous post, “The Art of the Blurb.”

With The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, I had a design in my head from the beginning. It took me a while to get it right, but even in its earliest formulation (the one now roaming the Web as a pirated graphic), the red velvet and the 18th-century sword figured prominently. Adding, then doubling (to represent either the dual nature of Ian/Percy or the heroine’s equality with the hero—take your pick), the scarlet pimpernel; finding the right sword and velvet; then making sure I wasn’t stealing anyone’s image—all these details took time. But the basic idea was already in place.

Not so with The Golden Lynx. The story contains three lynxes, for starters: a spirit animal who takes the form of an actual lynx, a gold necklace in the form of Scythian jewelry given to the heroine at a crucial moment by her older brother, and the heroine herself, who takes refuge from her troubles by becoming a female Scarlet Pimpernel whom the locals dub the Golden Lynx. I was so excited the day I discovered that Eurasian lynxes really are golden brown. And when I found the perfect circle (a Scythian panther) to represent the gold necklace.

My early versions of the cover featured all three: lynx front and center, girl shadowy in the background, jewelry next to her. Unfortunately, in my early period of ignorance, I failed to consider the copyright status of my first set of images. The lynx turned out to be the work of a Czech photographer. The girl came from a video published on Youtube by the Republic of Tatarstan. Public domain? No way to tell—I swear I looked, but there was no information even about the person who uploaded the video. The jewelry belongs to the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, which does allow people to download its images, although not for commercial use. And the Hermitage site does not include that particular image, which now no longer shows up in Google Images at all.

So in the best case, I would have had to find alternatives. A bigger problem, though, was the design itself. As my invaluable critique group pointed out, the actual lynx took over the cover. In the end, the story is about a girl, not a wildcat. The cover did not make this clear.

I shifted the elements around to emphasize the heroine and relegate her spirit guide to the background, then began trawling Shutterstock for images of girls around my heroine’s age. This one had the right attitude, although nothing about her screams “16th-century Turkic princess.”

I shifted the elements around to emphasize the heroine and relegate her spirit guide to the background, then began trawling Shutterstock for images of girls around my heroine’s age. This one had the right attitude, although nothing about her screams “16th-century Turkic princess.”  This one at least sports a costume plausible for my heroine masquerading as the Golden Lynx. But the girl’s demeanor, if culturally correct, seems rather demure for a tomboy defying every social convention because she’s mad at her new husband.

This one at least sports a costume plausible for my heroine masquerading as the Golden Lynx. But the girl’s demeanor, if culturally correct, seems rather demure for a tomboy defying every social convention because she’s mad at her new husband. Finally, I wised up and ran a search on Shutterstock for “Tatar bride.” Bingo. Rather surprisingly, even if we exclude the pictures of raw beef and sauce for fish, Shutterstock carries a remarkable number of photographs of actual Tatars.

With the addition of an Ottoman dagger, also from Shutterstock, and a beautiful Eurasian lynx courtesy of Bernard Landgraf (reused under a Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike 3.0 Unported license), I came up with the cover below. Perhaps a bit spare, but everything I tried adding made the result look cluttered. So in the end I left it as is. The black background will carry over nicely into the other books in this series, becoming a unifying theme. And the elements catch the eye even when reduced to thumbnail size, not an unimportant consideration in this day and age.

And please note, that although the manipulated lynx can be reused under the same terms (attribution/share-alike) as the original, the other images in this post were purchased from Shutterstock, so using them without buying your own license violates that company’s copyright.

For up-to-date publication information on The Golden Lynx, see http://www.fivedirectionspress.com.

For the story of the back cover, see my previous post, “The Art of the Blurb.”

Published on September 07, 2012 15:08

August 28, 2012

The Art of the Blurb

Or Why I Shouldn’t Try to Get a Job on Madison Ave.

You write a novel, and before you can publish it, you have to produce a blurb to go on the back. Seems simple enough, but for whatever reason, this is not my strength. I can dash off 450 pages without blinking an eye, but reduce those pages to three paragraphs? Ack. Shoot me now.

I didn’t realize my limitations at first. I felt quite proud of myself, in fact, having compressed the essentials of my soon-to-be-released Russian novel to a few telling paragraphs. I won’t burden you with the original version: it’s not important to the post. At the time, I was working on my cover (a story for next week’s post). When I thought it close to ready, I showed it to my friend Diana Holquist, who has not only published six novels and one nonfiction book of her own but used to work in advertising. She looked it over and said, “There’s too much information.”

Too much information? I’d left out 441.5 of the 442 pages. How could there be too much information?

Fortunately, Diana also included a couple of samples. And with a few tweaks from me, one of those samples gave rise to the following description, which will go to press in early September as the back cover of The Golden Lynx:

You’d think I’d learned my lesson. But if I had, I wouldn’t need to write this post. I could just send Diana a thank you card and move on. The Golden Lynx became just Act I of the story.

In Act II, my spouse—since I sometimes use the screen name Marguerite, we’ll call him Percy—decides to help me sell my first book, The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel. He’s very good at talking up my stuff, much better than I am, so I happily turn over my back cover copy and a list of reviews and links and let him go at it.

After a while, he wanders by and says, “Your reviews make the book sound interesting. I’d even like to read it.” A real concession, that, since historical romance is not his thing. I’m feeling good.

Then he hits me with the follow-up. “But the blurb—there’s too much information. If I picked that up in an airport bookstore, I’d have to drop it and run for the plane before I decided whether to plunk down my cash.”

Gulp. We’ve been married a long time, so even though my tongue tingles with the desire to say something rude, I don’t, because I suspect he’s right. Besides, it’s not like I’ve never heard this feedback before. I pull out a shorter version I’ve written for the library reading I’m giving in a month and show him that. Problem solved. Right?

“Nope,” he says. “Still too much information.” He makes some suggestions for improvement.

By now, I’m feeling more than a little cranky. I think evil thoughts about who in this family writes fiction and who doesn’t. About where I got the idea of writing the blurb that way in the first place. About how other people liked it.

But I don’t speak them. The point of writing is to connect with readers, not to shove my fingers in my ears and guard my right to be obscure. Suppose the other people weren’t telling the truth, because they didn’t want to deal with me being cranky? Plus Percy was the one who came up with that line about the “greatest hero has to save the greatest villain” line for Lynx.Maybe I should trust his instincts.

I grit my teeth, go back to my computer, take his suggestions seriously, and try again. And again, and a few more times. By the time I finish draft six, Percy is hiding in his office, wishing I would go away and not ask him for any more opinions. He looks like he’s remembering that poison research I did a few weeks back and wondering if it’s safe to eat dinner.

After many trials, and much input from the spouse, I came up with this new version. Does it make you want to read the book? (Hint: You may not want to tell me it has too much information.)

You write a novel, and before you can publish it, you have to produce a blurb to go on the back. Seems simple enough, but for whatever reason, this is not my strength. I can dash off 450 pages without blinking an eye, but reduce those pages to three paragraphs? Ack. Shoot me now.

I didn’t realize my limitations at first. I felt quite proud of myself, in fact, having compressed the essentials of my soon-to-be-released Russian novel to a few telling paragraphs. I won’t burden you with the original version: it’s not important to the post. At the time, I was working on my cover (a story for next week’s post). When I thought it close to ready, I showed it to my friend Diana Holquist, who has not only published six novels and one nonfiction book of her own but used to work in advertising. She looked it over and said, “There’s too much information.”

Too much information? I’d left out 441.5 of the 442 pages. How could there be too much information?

Fortunately, Diana also included a couple of samples. And with a few tweaks from me, one of those samples gave rise to the following description, which will go to press in early September as the back cover of The Golden Lynx:

WHO IS THE GOLDEN LYNX?

Russia, 1534.Elite clans battle for control of the toddler who will become their first tsar, Ivan the Terrible. Amid the chaos and upheaval, a masked man mysteriously appears night after night to aid the desperate people.

Or is he a man?

Sixteen-year-old Nasan Kolychev is trapped in a loveless marriage. To escape her misery, she dons boys’ clothes and slips away under cover of night to help those in need. She never intends to do more than assist a few souls and give her life purpose. But before long, Nasan finds herself caught up in events that will decide the future of Russia.

And so, a girl who has become the greatest hero of her time must decide whether to save a baby destined to become the greatest villain of his.

You’d think I’d learned my lesson. But if I had, I wouldn’t need to write this post. I could just send Diana a thank you card and move on. The Golden Lynx became just Act I of the story.

In Act II, my spouse—since I sometimes use the screen name Marguerite, we’ll call him Percy—decides to help me sell my first book, The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel. He’s very good at talking up my stuff, much better than I am, so I happily turn over my back cover copy and a list of reviews and links and let him go at it.

After a while, he wanders by and says, “Your reviews make the book sound interesting. I’d even like to read it.” A real concession, that, since historical romance is not his thing. I’m feeling good.

Then he hits me with the follow-up. “But the blurb—there’s too much information. If I picked that up in an airport bookstore, I’d have to drop it and run for the plane before I decided whether to plunk down my cash.”

Gulp. We’ve been married a long time, so even though my tongue tingles with the desire to say something rude, I don’t, because I suspect he’s right. Besides, it’s not like I’ve never heard this feedback before. I pull out a shorter version I’ve written for the library reading I’m giving in a month and show him that. Problem solved. Right?

“Nope,” he says. “Still too much information.” He makes some suggestions for improvement.

By now, I’m feeling more than a little cranky. I think evil thoughts about who in this family writes fiction and who doesn’t. About where I got the idea of writing the blurb that way in the first place. About how other people liked it.

But I don’t speak them. The point of writing is to connect with readers, not to shove my fingers in my ears and guard my right to be obscure. Suppose the other people weren’t telling the truth, because they didn’t want to deal with me being cranky? Plus Percy was the one who came up with that line about the “greatest hero has to save the greatest villain” line for Lynx.Maybe I should trust his instincts.

I grit my teeth, go back to my computer, take his suggestions seriously, and try again. And again, and a few more times. By the time I finish draft six, Percy is hiding in his office, wishing I would go away and not ask him for any more opinions. He looks like he’s remembering that poison research I did a few weeks back and wondering if it’s safe to eat dinner.

After many trials, and much input from the spouse, I came up with this new version. Does it make you want to read the book? (Hint: You may not want to tell me it has too much information.)

Have you ever wanted to rewrite your favorite novel—fix the heroine’s mistakes, win the hero’s heart?

Nina Pennington does. It makes her day when she lands the plum role as the heroine of The Scarlet Pimpernel in a class assignment based on a computer game. She knows she can win—until she realizes her one chance for success requires an alliance with her least-favorite fellow grad student, cast as the Scarlet Pimpernel himself.

The game challenges Nina in ways she never anticipated, and that least-favorite fellow grad student starts looking better by the minute. But then, she has always had a soft spot for the swashbuckling Scarlet Pimpernel.

Now Nina has to choose: win the game, or take a chance on love?

Published on August 28, 2012 14:44

August 18, 2012

Photo Albums of the World

A Whirlwind Tour

In “The Nation’s Photo Album” I discussed the royalty-free, mostly attribution-only collection of images and sounds maintained by the U.S. Library of Congress’s Digital Collections. As impressive as that resource is, it represents only a small part of the digital richness accessible through your web browser. So here I offer a brief overview, by category, of other places you can find usable art.

Note that not all these sources are quite as “public domain” as the Library of Congress. Some require permission, and may extract a usage fee, for anything other than noncommercial use. According to the helpful FAQs maintained by the Metropolitan Museum and the Smithsonian Institutions, posting to a blog, a social network, or a website is considered noncommercial so long as you do not accept advertising, charge a fee, or use the site as a store. Placing an image on the cover of a book you plan to sell may be considered commercial use, depending on the number of copies printed and whether you aim for a mass or an academic audience. Also at some institutions, not every image can be used. Where I know of restrictions, I list them, but you do have to check in each case.

That said, here are some more suggestions in a far from exhaustive list.

First off, I’d like to mention the photography version of Wikipedia: Fotopedia. Fotopedia photographs are uploaded by users under some version of the Creative Commons license.

Fotopedia has a number of free apps available for iDevices, available through the App Store on your device. These free collections offer a great way to search and surf for images, but you still need to use a browser to check the copyright information on photographs you want to use or repurpose. If you go to the main site at the link above and keep clicking the right arrow until you get to the search box, you can enter a search term for a part of the world, a geographic feature, or a category of people and see tens to thousands of gorgeous photographs. Click at bottom right of an image page, where it says “Some Rights Reserved,” to find out the exact terms of use for that shot. Some photographers permit commercial use with attribution; others don’t. Even those that don’t may choose to waive the restriction if you write to the address given on the image copyright page.

But to quote the Fotopedia Basics page: “The encyclopedia is not meant to stay on Fotopedia's website. You can embed widgets on your blog and website, share links with friends on Facebook and Twitter, and get them to vote on photos. Spread the photos and spread the word to the world! Just remember photographers take great photos and deserve to be recognized for their work.”

Two other good sites of free, public domain photographs and clip art are Microsoft’s Clip Art Galleryand MorgueFile. These have no restrictions that I know of, but do check around for a “terms of use” that may require attribution or impose limitations.

And, of course, the WANA Commons group on Flickr is growing every day: it must be close to 4,000 images by now. For more information, see the link in my previous post.