C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 59

March 1, 2013

Royal Purple

The British press has been in a flap the last couple of weeks in response to a lecture in which Hilary Mantel, the prizewinning author of Wolf Hall and Bringing Up the Bodies, sharpened her authorial scalpel on the new duchess of Cambridge and the late Princess Diana. Was Mantel on to something, or just being mean? Did she attack the royals or the press and society?

I don’t intend to take up any of those questions here. You can decide for yourself by reading Mantel’s “Royal Bodies” online. But Mantel mentions in passing the romance novelist Barbara Cartland, who happens to have been Princess Diana’s step-grandmother. Mantel says that she is “far too snobbish to have read” a Cartland novel, but that she assumes “they are stories in which a wedding takes place and they all live happily ever after. Diana didn’t see the possible twists in the narrative.” “She didn’t know the end of her own story.”

In short, Mantel invokes—perhaps unintentionally, perhaps not—the old canard that romance novels are the equivalent of the distaff that pricks Princess Aurora’s finger and sends her into a hundred-year sleep, and reading a book that concludes with a wedding and a fairy-tale ending forces you to believe that life plays out the same way. My buddy Diana Holquist has already tackled the romance novelist aspect of Mantel’s comments in this post. Today I’m talking about the second part: the readers.

Confession time: I used to read Barbara Cartland novels. I read quite a lot of them, in fact—probably about thirty—when I was in college. I read them with several of my close friends, and we thought they were a complete and total hoot. I lent one to my mother right after her hysterectomy, and I had to take it away from her because she was so busy laughing that she nearly tore out her stitches. I read Georgette Heyer, too, and Emilie Loring, but Cartland was, by far, the ideal study break. You could toss one off in an hour and a half, read the choice passages aloud to the rest of the group, chortle a bit, and get back to work.

Barbara Cartland went on to have a truly spectacular career: she published 723 novels and reportedly left another 160 to her estate. Hence my thirty constitutes such a tiny fraction of the whole that it would be negligible, were it not for one thing. Every Cartland novel has the same plot: beautiful (or potentially beautiful) virgin meets handsome, dashing, relatively young (but always older than she) nobleman and instantly falls in love. Something—usually several somethings—gets in the way, but sooner or later virgin and nobleman declare their love and marry or, if married early in the book, declare and consummate their love. The virgins are always innocent, the noblemen worldly, one or both of them has enough money to support a small country, and anything much beyond a kiss occurs only between a married couple and then behind closed doors.

And there are ellipses—lots and lots of ellipses. Whenever the virgin must interact with the man of her dreams, you can count on ellipses (my college friends and I referred to them as dot dot dot, as in “I love you dot dot dot Drogo. [Yes, even my sample included several heroes named Drogo—I have never personally known a human being named Drogo, have you?] I love you dot dot dot and I am dot dot dot yours, completely and absolutely yours. I dot dot dot always have been”).

The purple prose, the conviction that one look sets a person’s destiny forever, the bizarre twists dressing up the same underlying plot (American heiress loses 200 pounds, moves to her husband’s ducal estate, and goes unrecognized while she wins his heart in The Unknown Heart; Irish heiress dons dark glasses and moves to London, marries a duke who’s in love with her aunt, runs off to Paris and goes unrecognized as a pretend courtesan while she wins the duke’s heart in Desire of the Heart, the source of the Drogo quotation above), the cookie-cutter titles: it’s all hilarious. But is it, as Hilary Mantel implies, dangerous?

The purple prose, the conviction that one look sets a person’s destiny forever, the bizarre twists dressing up the same underlying plot (American heiress loses 200 pounds, moves to her husband’s ducal estate, and goes unrecognized while she wins his heart in The Unknown Heart; Irish heiress dons dark glasses and moves to London, marries a duke who’s in love with her aunt, runs off to Paris and goes unrecognized as a pretend courtesan while she wins the duke’s heart in Desire of the Heart, the source of the Drogo quotation above), the cookie-cutter titles: it’s all hilarious. But is it, as Hilary Mantel implies, dangerous?I suppose it could be, if anyone takes it seriously. But is that possible?

I can’t speak for Princess Diana. My acquaintance with her didn’t extend beyond watching her wedding in 1981 and endless glimpses on the nightly news thereafter. I wouldn’t presume to know what she read or what she thought about what she read. Perhaps, at nineteen, she did believe in fairy tales.

I can’t speak for Princess Diana. My acquaintance with her didn’t extend beyond watching her wedding in 1981 and endless glimpses on the nightly news thereafter. I wouldn’t presume to know what she read or what she thought about what she read. Perhaps, at nineteen, she did believe in fairy tales. I know I did. I read Heyer and Loring because I believed in fairy tales—or at least desperately wanted to believe in them, despite already suspecting that life was not that simple. When I grew older and acquired more experience, I stopped reading Loring in favor of more complicated stories; eventually, I stopped reading romances and moved on to other kinds of books—although I still love Georgette Heyer, who had a gift for characterization few other authors can match. And although I write romance into my own novels, my romances never quite fit the formula and remain secondary to the plot. I can’t make it work. I want something more realistic.

But even in my romance-reading heyday, Barbara Cartland’s fairy tale was too outrageous to swallow. It was funny four decades ago, and it’s even funnier now (yes, I found used copies of the American and Irish heiresses’ stories on Amazon.com). If Princess Diana believed that story for a moment, it can only have been because her life imitated it—for a few months, until she found out that she wasn’t playing the heroine’s part in her husband’s story after all. Then real life intervened, and she had to deal with it, just like everyone else. Maybe once in a while she reread the fairy tales for solace, until they became too painful and she put them aside.

Fairy tales aren’t real, even when we wish they could be. But just like a trip to the Caribbean, they can offer a fun place to escape—for an hour. Let’s not bash readers by assuming they don’t have the sense to know the difference.

Dame Barbara Cartland

Dame Barbara CartlandQueen of Romance (and Pink)

Published on March 01, 2013 15:53

February 22, 2013

Tasha Alexander Interview

As I mentioned at the end of my previous post, on Friday of last week, I had the great pleasure of interviewing Tasha Alexander for New Books in Historical Fiction. She had many fascinating things to say about her books, her writing career, her vision of Lady Emily as a character, and what drew her to explore Emily’s world. She also talks about Venice, Renaissance families, difficult people, and her plans for Emily's future adventures. The interview went live on Tuesday.

You need only click on the NBHF link below to access the podcast. Once there, you can also subscribe to future podcasts, explore the other channels, and—if you feel so inclined—donate to the New Books Network, which operates entirely with the help of unpaid volunteers and on the generosity of its founder, Marshall Poe.

The rest of this post comes from the NBHF page.

Well-brought-up Victorian ladies don’t expect their childhood nemeses to write from out of the blue, pleading for help because, as the nemesis so tactfully puts it, “what lady of my rank would associate with persons who investigate crimes?”

In this case, the crime is murder, and the summons brings Lady Emily Hargreaves post-haste from London to aid and support Contessa Emma Barozzi—née Callum, and the nemesis from Emily’s past—whose husband the Venetian police suspect of dispatching his own father with a medieval stiletto and fleeing with Emma’s inheritance, a cache of illuminated Renaissance manuscript books.

Although tempted to refuse Emma’s plea for help, Emily cannot abandon a fellow Englishwoman in the midst of crisis—or turn down an opportunity to overcome the petty dislikes of childhood. Moreover, Emily, through no fault of her own, has amassed a certain amount of experience in solving deadly crimes in London, Vienna, Istanbul, and rural France. With her husband, an agent of the British crown, she plunges into an unfamiliar, sometimes terrifying, but appealing world of art, gondolas, canals, decaying palazzi, back streets, brothels, bookstores, carnival figures, and ancient noble families with unresolved feuds that predate Romeo and Juliet. Soon Emily begins to suspect that the key to the mystery lies four centuries in the past, with links to the fifteenth-century ring found clasped in the victim’s dead hand.

This is the seventh of Lady Emily’s adventures, which began with And Only to Deceive. The next in the Lady Emily series, Behind the Shattered Glass, is due off-press in October 2013. On what Tasha has in store for her characters after that, you will have to listen to the podcast. She is a wonderful speaker: I promise you will not be disappointed. And, of course, read Death in the Floating City .

Published on February 22, 2013 13:38

February 15, 2013

Seven/Seven Blog Challenge

Louise West, a writer/member of Goodreads, recruited me for this blog challenge. I agreed—well, frankly, because it sounded like fun. The rules are simple. Post seven lines from p. 7 (or 77) of my work in progress; thank Louise for nominating me, with a link back to her blog; and talk seven other writers into participating by posting seven lines from the appropriate pages of their works in progress, thanking/linking to me, posting the challenge rules, and finding seven other authors to carry on the chain. A pyramid scheme, yes, but one involving words, not money. If nothing else, readers of our blogs may find other blogs they would like to follow. Some of you may even discover new books to read—or new authors to keep up with.

So here goes. First, the seven lines from p. 7 of The Winged Horse (Legends of the Five Directions 2: East). The “he” is Bahadur, leader of a nomadic Tatar horde. Firuza is his daughter (heroine of the novel), and Roxelana his favorite concubine. Although he does not know it, Bahadur is deathly ill. Through the smoke hole of his tent, he watches dawn break.

Good. He welcomed the light. In the flickering lamps, he could barely see.

But he could hear. The closest voice belonged to Firuza, who clasped his hand and crouched beside his bed. Beyond her knelt the ring of keening women, led by Roxelana. His indulgence of the night before had left him with a head that throbbed in rhythm with their sobbing breaths.

He frowned at the smoke hole. Keening. For whom? He was not dying. What demon possessed these women, that they should inflict their woes on him?

Tatar khan holding court

Clipart.com no. 77252

The seven writers who have agreed to keep the ball rolling are:

Julia Grace

Courtney J. Hall

Amanda McCrina

Diane V. Mulligan

Janet Olshewsky

Sandra Saidak

Hazel West (Hazel has a second blog devoted to Scottish history)

Most of them write historical fiction, like me, but specializing in very different times and places.

And many thanks and a shout out to Louise West, who tagged me in the first place!

Also, had a fabulous interview today with Tasha Alexander, author of the Lady Emily mysteries, of which the latest is Death in the Floating City, for New Books in Historical Fiction. I'll have more about that next week, after the podcast goes live.

Published on February 15, 2013 16:18

February 8, 2013

The Ever-Changing Story

So, way back when—July 2012, to be precise—I wrote a blog post called “Pantser Learns to Plot, Courtesy of Storyist.” Pantsers, in novel-writing lingo, are writers who put together a story “by the seat of their pants”—meaning that they jump in and follow the Muse wherever she takes them. Plotters, in contrast, don’t move a muscle until they have a scene by scene outline, clear settings, and well-defined characters. People tend to favor one style over the other, although most authors operate not at the extremes of the continuum but somewhere in the middle. There are other ways of characterizing writers, but for the moment, let’s stick with this one.

Each style has its advantages. Pantsers revel in the joy of watching their story unfold but may follow an appealing digression right into a maze, necessitating extensive rewriting. Plotters stay on track better and generally need to do less structural overhaul, sometimes at the expense of serendipity and naturalness.

The interesting point to me is how ingrained writing style is. Back in July 2012, I structured an entire outline, just like a plotter. I drew up goal, motivation, and conflict charts for each significant character. I assigned traits to my hero and heroine, deciding she should write poetry and he should have enough interest in poetic forms and expressions to appreciate her skill. To determine the hero’s fate, I outlined a series of culturally appropriate challenges: a wrestling match, a poetry contest, and a racing game called “Kiss the Girl.” I decided the character of the antagonist, gave him a history and a clear motive, complex enough to keep him from being an irredeemable bad guy.

I’m really glad I did all that work, because as a result, I know that I have a story. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end. It has character growth. It has structure.

Except that I am halfway through the rough draft, and I can see that at most one-third of the original outline will ever make it into the finished novel. The poetry fell by the wayside first, and the heroine seems fine without it (good thing—I never quite figured out how I would master the forms of 16th-century Tatar poetry). The wrestling match turned into a single punch to the jaw, the race into a squabble between lovers not yet ready to admit how they feel about each other (although if my characters give me half a chance, I’m determined to bring “Kiss the Girl” back in—it’s much too good a custom to toss aside). Even the antagonist has shifted as I’ve made his acquaintance and decided that I have long-term plans for him. I’m going to have to build up someone else, who has been lurking in the background waiting for the right moment, and complicate his character—or hers. Because the hero needs someone to defeat, and if he defeats the original antagonist as thoroughly as the plot requires, there go the long-term plans.

This happens, I’ve concluded—and if you write by the seat of your pants, you’ll know exactly what I mean—because I discover my characters by watching them in action. I can set out things for them to do and reasons why they should do them, but until I see them in motion, I don’t fully grasp what kind of people they are, how they will react to this opportunity or that obstacle. They constantly surprise me.

Writing The Winged Horse

Writing The Winged Horse

(Not exactly me, but the horse is perfect)

Clipart no. 9744072

My critique group constantly surprises me, too (and believe me, I’m grateful), forcing me to rethink by asking, “Why would X do/say that?” Then I stop to wonder, and in wondering I uncover new facets of the characters’ lives. Sometimes I find out why X did or said whatever I wrote down. Other times, I realize X never could say or do that under the circumstances in which I have placed him or her, and I have to figure out what X would say or do. Even then, I have to write it down and see if it fits. If not, I throw the scene out and try again. Through such fits and starts, I gradually discern who the character is.

This post is not a manifesto on how to write. I love reading about the craft of writing, but in the end what works, works. Different people have different styles. And as I mentioned above, I’m glad I learned to plot. I’ll do it again for my next novel, and for every novel after that. It gets me over blank-page syndrome and reassures me that this book will end up somewhere other than a blind alley. If less than 50 percent of the details make it into the story—well, extra plot points and character traits always come in handy.

But however much I may appreciate plotting as a skill, I have to accept that in my heart I’m a pantser, and I probably always will be. For me the fun of writing lies in the discovery of a world I didn’t suspect existed, one populated by fictional people with lives and ways of thinking that I cannot always predict, because they emerge from my subconscious mind, a trove of magic and mystery. And I’m not just okay with that, I’m happy with it.

What about you? Do your fictional people ever go their own way?

Each style has its advantages. Pantsers revel in the joy of watching their story unfold but may follow an appealing digression right into a maze, necessitating extensive rewriting. Plotters stay on track better and generally need to do less structural overhaul, sometimes at the expense of serendipity and naturalness.

The interesting point to me is how ingrained writing style is. Back in July 2012, I structured an entire outline, just like a plotter. I drew up goal, motivation, and conflict charts for each significant character. I assigned traits to my hero and heroine, deciding she should write poetry and he should have enough interest in poetic forms and expressions to appreciate her skill. To determine the hero’s fate, I outlined a series of culturally appropriate challenges: a wrestling match, a poetry contest, and a racing game called “Kiss the Girl.” I decided the character of the antagonist, gave him a history and a clear motive, complex enough to keep him from being an irredeemable bad guy.

I’m really glad I did all that work, because as a result, I know that I have a story. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end. It has character growth. It has structure.

Except that I am halfway through the rough draft, and I can see that at most one-third of the original outline will ever make it into the finished novel. The poetry fell by the wayside first, and the heroine seems fine without it (good thing—I never quite figured out how I would master the forms of 16th-century Tatar poetry). The wrestling match turned into a single punch to the jaw, the race into a squabble between lovers not yet ready to admit how they feel about each other (although if my characters give me half a chance, I’m determined to bring “Kiss the Girl” back in—it’s much too good a custom to toss aside). Even the antagonist has shifted as I’ve made his acquaintance and decided that I have long-term plans for him. I’m going to have to build up someone else, who has been lurking in the background waiting for the right moment, and complicate his character—or hers. Because the hero needs someone to defeat, and if he defeats the original antagonist as thoroughly as the plot requires, there go the long-term plans.

This happens, I’ve concluded—and if you write by the seat of your pants, you’ll know exactly what I mean—because I discover my characters by watching them in action. I can set out things for them to do and reasons why they should do them, but until I see them in motion, I don’t fully grasp what kind of people they are, how they will react to this opportunity or that obstacle. They constantly surprise me.

Writing The Winged Horse

Writing The Winged Horse(Not exactly me, but the horse is perfect)

Clipart no. 9744072

My critique group constantly surprises me, too (and believe me, I’m grateful), forcing me to rethink by asking, “Why would X do/say that?” Then I stop to wonder, and in wondering I uncover new facets of the characters’ lives. Sometimes I find out why X did or said whatever I wrote down. Other times, I realize X never could say or do that under the circumstances in which I have placed him or her, and I have to figure out what X would say or do. Even then, I have to write it down and see if it fits. If not, I throw the scene out and try again. Through such fits and starts, I gradually discern who the character is.

This post is not a manifesto on how to write. I love reading about the craft of writing, but in the end what works, works. Different people have different styles. And as I mentioned above, I’m glad I learned to plot. I’ll do it again for my next novel, and for every novel after that. It gets me over blank-page syndrome and reassures me that this book will end up somewhere other than a blind alley. If less than 50 percent of the details make it into the story—well, extra plot points and character traits always come in handy.

But however much I may appreciate plotting as a skill, I have to accept that in my heart I’m a pantser, and I probably always will be. For me the fun of writing lies in the discovery of a world I didn’t suspect existed, one populated by fictional people with lives and ways of thinking that I cannot always predict, because they emerge from my subconscious mind, a trove of magic and mystery. And I’m not just okay with that, I’m happy with it.

What about you? Do your fictional people ever go their own way?

Published on February 08, 2013 13:26

February 1, 2013

Speaking of Faith

I had no sooner published my last post, “Achieving Stardom,” when my radio came on Sunday morning—as usual set to Krista Tippett’s weekly interview show,

On Being

. As luck would have it, Krista was interviewing Seth Godin, an Internet pioneer who has not only fascinating ideas on marketing but the sales history to support them. He has turned several books into Amazon.com bestsellers without either traditional publishing props or the contemporary sins of spamming his social network friends or faking reviews. You can find out more about the show, listen to it online, or download the podcast at

The Art of Noticing, and then Creating

.

I had no sooner published my last post, “Achieving Stardom,” when my radio came on Sunday morning—as usual set to Krista Tippett’s weekly interview show,

On Being

. As luck would have it, Krista was interviewing Seth Godin, an Internet pioneer who has not only fascinating ideas on marketing but the sales history to support them. He has turned several books into Amazon.com bestsellers without either traditional publishing props or the contemporary sins of spamming his social network friends or faking reviews. You can find out more about the show, listen to it online, or download the podcast at

The Art of Noticing, and then Creating

.I hadn’t initially intended to write a follow-up to last week’s post. But listening to Seth and Krista confirm some of what I had written, it occurred to me that I had not addressed a central question. Yes, it makes sense to trust the process, to accept that it takes longer than most of us might like to get the word out and find loyal readers rather than engage in deceptive or dysfunctional tactics born of desperation. But how do we know our faith is justified? So, in a tip of the hat to Krista, I have titled this post after the original name of her show, Speaking of Faith.

Let me say up front that I have no guru-type answer to my question, which is on the surface a circular one. Success, sooner or later, justifies an author’s faith that success will arrive. But the standards that determine success vary. Beautifully written books may not sell well—or they may win a major award and become bestsellers. Terribly written books may get million-dollar contracts but tank in the market—or not. Some indie books I have read went to print too soon (keep in mind that all such judgments are subjective—these books appear unpolished to me). Others make me wonder what had to go wrong with publishing that an agent and editor didn’t snap them up. So what’s your standard: good, famous, moneymaking? And how do you determine if you’ve met it?

What complicates the question of faith is a truth about writing that is not universally acknowledged, although most writers recognize it at some point in their careers. Good writers, experienced writers—like most expert artists—make the craft of writing look simple. As a result, readers and newbie writers think that anyone can write a novel, just as beginning dancers expect to whip off a triple pirouette after two or three classes. My first novel will see the light of day only if I run out of other stories and decide to rewrite it from scratch. It was terrible, but I had no idea. I sent it to agents and was amazed when they rejected it. Now I know why. Last time I tried to read it, I couldn’t get past chapter 3.

I tell this embarrassing story because it applies to every beginning writer. Some novels need to die. They don’t merit the leap of faith that will keep them in circulation. But that is not the same thing as saying they never deserved to live in the first place. Because the takeaway from this post is: everyone writes bad novels at first. There is no other way to learn the craft. You have to write and read about writing and show your work to other writers and rewrite and rewrite and rewrite. And if the first book is horrible, let it die. Start another, then a third and a fourth until you produce one that works.

And that, I think, is where the issue of faith comes in. It’s not only a question of having faith that a good book will find its market. Even more important is having faith that you, the artist, have the capacity to create a book that deserves a market. Trust that you can write a bad novel, send it out, have it fail, and not give up. Believe that the next novel will be better, and the one after that better still. And one day, even if you never spam your friends or fellow readers and you refuse to fake reviews for yourself or others, you will write a book that other people want to read. A book that people will pay to read and recommend to their friends. Which in the end is what you want, isn’t it?

To end on a lighter note, if you’d like to see the reviews system in all its glorious, untrammeled goofiness, without spamming and without manipulation—other than the input of those reading the reviews—type the words “bic lady pens” into the search box on Amazon.com. I haven’t laughed so hard in years. In their wacky way, the reviews are a triumph of human ingenuity over machine logic. And if you’d like to know what I mean by that, leave a comment.

Thanks to Seth Godin and Krista Tippett for the inspiration.

News Flash: Historical Fictionistas, a group on the Internet book club Goodreads, has chosen The Golden Lynx as its Featured Author Group Read for March 2013. Many, many thanks to the group moderators and all the members who voted for my novel. May you enjoy reading the book at least half as much as I enjoyed writing it!

Image purchased from Clipart.com, no. 21985679.

Published on February 01, 2013 15:41

January 25, 2013

Achieving Stardom

As you’ve heard me say before in this blog, marketing is tough. Of all the elements that an indie-published writer has to take on—editing, typesetting, cover design, website design, blogging—marketing and promotion seem to be the two least suited to the personality of people who happily spend years of their lives chronicling the lives of fictional people while real people clamor for their attention.

As you’ve heard me say before in this blog, marketing is tough. Of all the elements that an indie-published writer has to take on—editing, typesetting, cover design, website design, blogging—marketing and promotion seem to be the two least suited to the personality of people who happily spend years of their lives chronicling the lives of fictional people while real people clamor for their attention.Nor does the marketing problem affect only indie-published writers. Small presses have small budgets, little of which goes to promotion. Even big presses prefer to spend their dollars where they can expect the greatest returns: the few stars get book tours and television spots; the mid-list and niche authors don’t.

So marketing is tough. It takes grit and perseverance and creativity, a thick skin and an agile mind, a willingness to tackle new approaches and endure a certain amount of discomfort. Most of all, it takes patience, which assumes trust in the value of one’s work and confidence that sooner or later a book’s readers will find it. But that is precisely where many authors stumble. In their fear that they won’t make sales right away, desperate authors alienate the very people they most need to impress: their readers.

I see it on Goodreads all the time. No matter how often group moderators and site operators post the rules of engagement, certain writers leap into a new group and begin posting some version of “buy my book!” in a dozen different threads, as if the other group members were sales on the hoof. What usually happens is that the moderators label them spammers and exile them. By pushing sales first and foremost, these writers end up making none.

Let me hasten to add that not all Goodreads writers pester other group members, by any means. But enough of them do that in one group I joined, another member went out of her way to comment on how nice it was to interact with a writer who had not tried to flog her book to the group. Which, when you think about it, is a sad situation—not just for the readers constantly dodging hungry authors, but for the authors who deny themselves the pleasure of conversation in the belief that sales are the only measure of their success.

Still, the situation on Goodreads is mild compared to what happens in other online venues—not least because the site operators and the group moderators act as enforcers and delete authors who refuse to get the point. Meanwhile, the manipulation of social networks and online review systems proceeds apace. At the heart of the whole mess is the belief, true or false, that search algorithms determine a book’s visibility and therefore the author’s sales.

The undermining of the Amazon.com review system is not new. Stories have surfaced for some time about people gaming the system. At the thin end of the wedge, these schemes involve “sock puppets,” close relatives and friends whom the writer asks to submit a glowing review. So long as the person genuinely enjoyed the book, I don’t have a big problem with sock puppets. Non-writers often see automated requests for reviews as an annoyance, so pointing out that they can improve a book’s sales seems like a violation only if you threaten to block Aunt Mary from Thanksgiving dinner if she gives you less than five stars. After all, asking people to review a book honestly, including sending them a free copy for that purpose, is standard practice in publishing.

But the attacks on the review system go far beyond sock puppets. A few months ago, it came out that people had been buying or otherwise faking five-star reviews (by themselves submitting or encouraging others to submit multiple positive reviews under pseudonyms, say). On Monday, David Streitfeld reported in the New York Times (“Swarming a Book Online”) that a group of fans had used social media to organize a campaign against a book they disliked. The fans overwhelmed the author’s page on Amazon.com with one-star reviews. These fans were readers, but previous incidents have involved writers trashing other authors’ books while praising their own. So far as I know, no author has yet organized an online campaign to take down a competitor, but it’s not hard to imagine that day arriving.

I hope it never does. Because manipulating the system diminishes the importance of all reviews, both good and bad. Most readers have more options than time. If authors, in a desperate desire to ramp up their own sales at any cost, teach readers that reviews are unreliable, no one benefits. Honest writers lose, because their five-star reviews look fake. Unfairly targeted writers lose, because their books die unread. But the desperate writers lose, too, just as they lose when they spam readers’ groups on Goodreads. A reader who buys a book because of a lie will not buy another book from that author, ever. So faking reviews is not even good marketing strategy.

Marketing is tough. Building a readership takes time. No need to make the process tougher for everyone by spamming or lying.

Image Clipart no. 19859517.

Published on January 25, 2013 13:35

January 18, 2013

Playing with Words

What do editors do? I think it’s fair to say that the popular perception of editors—especially among writers who have not worked with one (and maybe a few who have)—is of a martinet whacking away at punctuation and spelling errors and generating ghastly Word documents covered in the virtual equivalent of red ink. Like the stereotyped librarian of legend, this imagined editor is stern, unyielding, and hovering on the edge of cuckoo. Definitely not the kind of person anyone wants to hang out with at neighborhood parties. The files they generate haunt a writer’s nightmares. Oh no, not the Comma Wars!

What do editors do? I think it’s fair to say that the popular perception of editors—especially among writers who have not worked with one (and maybe a few who have)—is of a martinet whacking away at punctuation and spelling errors and generating ghastly Word documents covered in the virtual equivalent of red ink. Like the stereotyped librarian of legend, this imagined editor is stern, unyielding, and hovering on the edge of cuckoo. Definitely not the kind of person anyone wants to hang out with at neighborhood parties. The files they generate haunt a writer’s nightmares. Oh no, not the Comma Wars!Well, it’s true, correcting punctuation, spelling, and usage is part of editing. We’re talking about copy editors here, not the many other kinds of editors who work at publishing houses. And the rules governing house style, in particular, often seem arcane. One publisher capitalizes where another does not. One writes out numbers under a hundred; the next uses arabic numerals for everything over ten. Tranquility or tranquillity? It’s anyone’s guess. The invocation of semi-magical authorities—in the United States, these are Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary and the Chicago Manual of Style—has stopped many a writer’s protest in its tracks. Even then, there are always exceptions. The copy editor must remember the rules, not just in general but for each specific house. The baffled author has to hang on and hope it all makes sense someday.

But fixing grammatical and spelling errors is a small part of editing. And thank goodness, because it’s a job that bores most editors, too. We do it—because someone has to, or the publisher looks sloppy—but 450 pages of misplaced commas exhaust the editor every bit as much as they do the author staring at red ants marching through his or her text. After about four hours, my brain starts spinning, and I can’t see anything. My eyes roll around in my head like a Looney Tunes character. I have to do something else for the rest of the day. And I’ve been editing for twenty years.

So editors don’t love punctuation, especially. We love words. More than words, we love language—language as a means of conveying ideas. Developmental editors (book doctors) overhaul fictional prose in a big way, moving entire passages and chapters, demanding that authors observe the basic structural principles of story and characterization. Copy editors (also called line editors) work paragraph by paragraph, line by line, word by word to ensure that every syllable counts, every thought achieves its fullest and most elegant expression. English possesses an amazing vocabulary, in which a single well-chosen word can encapsulate an image that requires entire phrases in other languages. Although novelists do need to worry about jerking their readers out of their fictional worlds to hunt for a dictionary, used judiciously that vast treasure trove of words—each with its own nuances and connotations—is a writer’s most precious resource. Editors find the word that zings: the verb strong enough to stand without an adverb; the adjective that pinpoints a character; the combination that sounds natural without descending into cliché.

Many editors also write—and when we write, we look for editors who can prune our prose where it counts and add the telling phrase that explains something we’ve taken for granted. Editors who will send our prose soaring into the stratosphere. Because the editor is the author’s first and most conscientious reader. Every single one of us lives inside his or her own head, unable to imagine how the images that seem so vivid to us can fall flat on the page, failing to communicate with someone who lacks our own specific knowledge and understanding and way of looking at the world. Editors bridge that gap.

And now, my secret. Precisely because I am an editor, as a writer I am a terrible editee (to coin a phrase—bet you didn’t expect that!). I hate people touching my prose. When I see those red ants, my skin crawls. I have to force myself to stop and think about whether, in fact, the person editing me has spotted an ambiguity that escaped me, solved a problem I didn’t believe existed with a felicity that I did not (or could not) muster. Sometimes the editor hasn’t. More often, the editor has. Because she cared enough to read my draft, ponder what I wanted to say, and find a better—clearer, stronger, more beautiful—way to say it.

So yes, authors need editors. Not just editors who will fix their commas (although a misplaced comma can completely change your meaning), but editors who love their books enough to free them from the unavoidable constraints of solipsism and let them fly.

Images purchased from Clipart.com (nos. 20413458 and 21791704).

Published on January 18, 2013 16:27

January 11, 2013

Stranger Than Fiction

I write historical fiction, to a large degree, to fill in the blanks, by which I mean to portray the many aspects of life in my particular time and place—sixteenth-century Russia—that we can only imagine based on our own experience, because sources that would contain that information are not (and often have never been) available. Those impenetrable elements of life happen to be the very things that interest people most, the things that make us human. How did it feel to be a teenage girl married off to a stranger to fulfill the political agenda of your parents? How does a woman cope with seeing half of her children—or all her children—die before the age of five? Suppose your gifts lie in painting icons, but your class and your gender require you to spend your life attacking your fellow man with sword and pike, lest he attack and kill you first? What did the past look like, sound like, smell like?

Answering these questions demands that a novelist supply historically accurate, or at least historically plausible, details that turn the dry recitation of facts into a story. Then, by creating recognizably human characters and sending them on a journey—even a journey that no one living today expects to undertake—the novelist gives that story meaning and life. Skilled fingers pluck the strings of history and make them sing.

The process is not perfect. By applying imagination, we inevitably distort the historical record—how much depends on the writer. At the same time, by exploring the emotions that drive any series of events and by looking at those events from different (but specific) perspectives, a good historical novelist can let the past unfold before the reader’s eyes, make it more accessible than a purely factual account. Although fancy does not supplant fact, well-conceived, well-written fancy can reveal a truth that simple facts obscure.

But what happens when history, in effect, subsumes fiction and twists storytelling to serve its own ends? One example of such an overlap between fact and fiction can be seen in the Moscow show trials of 1936–38.

In 1936, Joseph Stalin decided to eliminate any communist leader with sufficient prestige to threaten his monopoly on power. In what became known as the Great Terror, he instigated a series of show trials, with scripts written by his political police and entirely false charges, designed to cover up the mistakes of his forced industrialization and collectivization drives by blaming his rivals—especially his arch-rival, Leon Trotsky, by then in exile from the USSR.

The first trial succeeded in terms of Stalin’s larger goal: the political police forced the defendants to cooperate, confessing their “crimes” in open court. Convicted of plotting against Stalin, the leaders were promptly shot. The purges rippled out from the center, sweeping up hundreds of thousands of mid-level bureaucrats and intellectuals throughout the Soviet Union.

But the international community remained skeptical of trials that relied solely on confessions. So for the next show trial, held in 1937, Stalin’s police selected five witnesses to corroborate the faked charges against a new group of defendants. This month on New Books in Historical Fiction I talk with Julius (Jay) Wachtel, whose novel Stalin’s Witnesses (Knox Robinson Publishing, 2012) explores the identity, careers, and psychology of these five men—and especially of Vladimir Romm, a journalist, diplomat, and Soviet spy who served in Washington, DC, immediately before his recall and arrest in August 1936. Jay asks probing questions about the system that produced the show trials; the many small compromises that ordinary people, including his five witnesses, made with their consciences; and the means by which those compromises turned history into a fantastical theatrical performance. Our interview should be available by the middle of next week.

Listen to it. Read the book. If you do, the next time someone tells you that truth is stranger than fiction, you won’t hesitate to admit that they’re right.

Answering these questions demands that a novelist supply historically accurate, or at least historically plausible, details that turn the dry recitation of facts into a story. Then, by creating recognizably human characters and sending them on a journey—even a journey that no one living today expects to undertake—the novelist gives that story meaning and life. Skilled fingers pluck the strings of history and make them sing.

The process is not perfect. By applying imagination, we inevitably distort the historical record—how much depends on the writer. At the same time, by exploring the emotions that drive any series of events and by looking at those events from different (but specific) perspectives, a good historical novelist can let the past unfold before the reader’s eyes, make it more accessible than a purely factual account. Although fancy does not supplant fact, well-conceived, well-written fancy can reveal a truth that simple facts obscure.

But what happens when history, in effect, subsumes fiction and twists storytelling to serve its own ends? One example of such an overlap between fact and fiction can be seen in the Moscow show trials of 1936–38.

In 1936, Joseph Stalin decided to eliminate any communist leader with sufficient prestige to threaten his monopoly on power. In what became known as the Great Terror, he instigated a series of show trials, with scripts written by his political police and entirely false charges, designed to cover up the mistakes of his forced industrialization and collectivization drives by blaming his rivals—especially his arch-rival, Leon Trotsky, by then in exile from the USSR.

The first trial succeeded in terms of Stalin’s larger goal: the political police forced the defendants to cooperate, confessing their “crimes” in open court. Convicted of plotting against Stalin, the leaders were promptly shot. The purges rippled out from the center, sweeping up hundreds of thousands of mid-level bureaucrats and intellectuals throughout the Soviet Union.

But the international community remained skeptical of trials that relied solely on confessions. So for the next show trial, held in 1937, Stalin’s police selected five witnesses to corroborate the faked charges against a new group of defendants. This month on New Books in Historical Fiction I talk with Julius (Jay) Wachtel, whose novel Stalin’s Witnesses (Knox Robinson Publishing, 2012) explores the identity, careers, and psychology of these five men—and especially of Vladimir Romm, a journalist, diplomat, and Soviet spy who served in Washington, DC, immediately before his recall and arrest in August 1936. Jay asks probing questions about the system that produced the show trials; the many small compromises that ordinary people, including his five witnesses, made with their consciences; and the means by which those compromises turned history into a fantastical theatrical performance. Our interview should be available by the middle of next week.

Listen to it. Read the book. If you do, the next time someone tells you that truth is stranger than fiction, you won’t hesitate to admit that they’re right.

Published on January 11, 2013 17:26

January 4, 2013

Ghosts of Christmas Future

As promised in my previous post, “Ghosts of Christmas Past,” this week I’m looking forward, not back.

Now, there are two ways to handle these predictive posts (probably more, but humor me). One is to survey the entire publishing industry and make predictions about what’s likely to happen before December 31, 2013. For that kind of post, see Kristen Lamb’s blog. There are others out there, including a long and interesting post by Mark Coker, founder of Smashwords. But Kristen, I think, has called it pretty much right—or at least, pretty much as I see it.

This is not that kind of post. Here I review where I expect to be a year from now, both personally as a writer and in terms of projects I’m involved with. Although some of my personal goals may not have huge relevance for others, they are in their own way evidence of the evolving picture of publishing in 2013. Other goals have interest beyond my personal concerns, so for their sake, do read on.

First off, I hope that by the end of 2013, I will have finished and published book 2 (East) of my Legends of the Five Directions series, The Winged Horse. I already have one-third of an initial draft plus a demo cover and a full outline, although I’ve already deviated so far from the outline that it acts more as a set of suggestions than an actual plan. If life treats me well (i.e., gives me enough free time), I will even start work on book 3 (North), The Swan Princess. I already have basic ideas for that one, although I haven’t begun to sketch it out yet. The plan is to bring it out in 2014.

I expect to issue Winged Horse through Five Directions Press, the small publisher that I started with my critique group partners. I also expect Five Directions Press itself to grow this year. We should have two new titles out in the first quarter of 2013: Seeking Sophia, by Ariadne Apostolou; and Saving Easton, by Courtney J. Hall. Ariadne has a series of novellas near completion in addition to Seeking Sophia, so she should have two books out by the end of 2013. Courtney has become a writing dynamo, so I would not be surprised if she finished another book. But even without a second from Courtney, that would mean four new titles, if all goes well, and two new authors—for a total of seven books and four authors by the end of the year. Not exactly Big Six (or is it Four?) territory, but not totally shabby either. You can find out more at http://www.fivedirectionspress.com/books.

That brings me to promotion, a job at which I admit to being, well, challenged. I can probably attend the Slavic studies conference this year, which will help with the Legends of the Five Directions books. I may run a Goodreads giveaway for The Golden Lynx; I’m waiting to see if the last one, for The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, had any effect on sales (for more on that, see “Potlatch and Publishing”). I'm giving a talk at the local Rotary club in March; the rest is just a question of keeping up with Goodreads, trading author interviews where possible, letting people know about the books, etc., etc.

That brings me to promotion, a job at which I admit to being, well, challenged. I can probably attend the Slavic studies conference this year, which will help with the Legends of the Five Directions books. I may run a Goodreads giveaway for The Golden Lynx; I’m waiting to see if the last one, for The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, had any effect on sales (for more on that, see “Potlatch and Publishing”). I'm giving a talk at the local Rotary club in March; the rest is just a question of keeping up with Goodreads, trading author interviews where possible, letting people know about the books, etc., etc.

I definitely plan to continue, and probably expand, my interviews for New Books in Historical Fiction. I love the conversations; the books are great; and I may even master the blasted software by the time December rolls around. So far, six authors have agreed to talk. More or less in order, they are Jay Wachtel, B.A. Shapiro, Bill McCormick, Tasha Alexander, Laurie R. King, and Marie Macpherson. There are others I’d love to interview, but I have yet to contact them, since I don’t want to keep them waiting forever. By April I should have a new list.

And somehow, I’ll find topics for 51 more weekly blog posts. What will I say? The task seems quite daunting—until I remember that this is already post no. 34….

Now, there are two ways to handle these predictive posts (probably more, but humor me). One is to survey the entire publishing industry and make predictions about what’s likely to happen before December 31, 2013. For that kind of post, see Kristen Lamb’s blog. There are others out there, including a long and interesting post by Mark Coker, founder of Smashwords. But Kristen, I think, has called it pretty much right—or at least, pretty much as I see it.

This is not that kind of post. Here I review where I expect to be a year from now, both personally as a writer and in terms of projects I’m involved with. Although some of my personal goals may not have huge relevance for others, they are in their own way evidence of the evolving picture of publishing in 2013. Other goals have interest beyond my personal concerns, so for their sake, do read on.

First off, I hope that by the end of 2013, I will have finished and published book 2 (East) of my Legends of the Five Directions series, The Winged Horse. I already have one-third of an initial draft plus a demo cover and a full outline, although I’ve already deviated so far from the outline that it acts more as a set of suggestions than an actual plan. If life treats me well (i.e., gives me enough free time), I will even start work on book 3 (North), The Swan Princess. I already have basic ideas for that one, although I haven’t begun to sketch it out yet. The plan is to bring it out in 2014.

I expect to issue Winged Horse through Five Directions Press, the small publisher that I started with my critique group partners. I also expect Five Directions Press itself to grow this year. We should have two new titles out in the first quarter of 2013: Seeking Sophia, by Ariadne Apostolou; and Saving Easton, by Courtney J. Hall. Ariadne has a series of novellas near completion in addition to Seeking Sophia, so she should have two books out by the end of 2013. Courtney has become a writing dynamo, so I would not be surprised if she finished another book. But even without a second from Courtney, that would mean four new titles, if all goes well, and two new authors—for a total of seven books and four authors by the end of the year. Not exactly Big Six (or is it Four?) territory, but not totally shabby either. You can find out more at http://www.fivedirectionspress.com/books.

That brings me to promotion, a job at which I admit to being, well, challenged. I can probably attend the Slavic studies conference this year, which will help with the Legends of the Five Directions books. I may run a Goodreads giveaway for The Golden Lynx; I’m waiting to see if the last one, for The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, had any effect on sales (for more on that, see “Potlatch and Publishing”). I'm giving a talk at the local Rotary club in March; the rest is just a question of keeping up with Goodreads, trading author interviews where possible, letting people know about the books, etc., etc.

That brings me to promotion, a job at which I admit to being, well, challenged. I can probably attend the Slavic studies conference this year, which will help with the Legends of the Five Directions books. I may run a Goodreads giveaway for The Golden Lynx; I’m waiting to see if the last one, for The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, had any effect on sales (for more on that, see “Potlatch and Publishing”). I'm giving a talk at the local Rotary club in March; the rest is just a question of keeping up with Goodreads, trading author interviews where possible, letting people know about the books, etc., etc.I definitely plan to continue, and probably expand, my interviews for New Books in Historical Fiction. I love the conversations; the books are great; and I may even master the blasted software by the time December rolls around. So far, six authors have agreed to talk. More or less in order, they are Jay Wachtel, B.A. Shapiro, Bill McCormick, Tasha Alexander, Laurie R. King, and Marie Macpherson. There are others I’d love to interview, but I have yet to contact them, since I don’t want to keep them waiting forever. By April I should have a new list.

And somehow, I’ll find topics for 51 more weekly blog posts. What will I say? The task seems quite daunting—until I remember that this is already post no. 34….

Published on January 04, 2013 16:21

December 28, 2012

Ghosts of Christmas Past

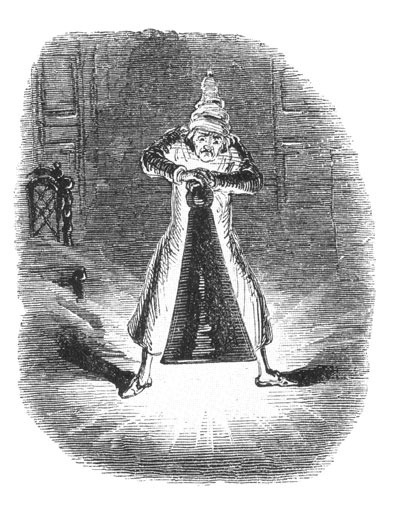

Scrooge and the Ghost

Scrooge and the Ghostof Christmas Past

Original 1843 illustration

by John Leech

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Since this is my last blog post of the year, tradition calls for some kind of summary: best/worst books of 2012; writers lost or writers who emerged; favorite quotations of the year; resolutions and how well I kept them—something along these lines. Well, who am I to buck tradition?

Thanks to middle-aged memory loss, I can’t remember all the good books I read this year or the great quotations I heard, and it seems mean-spirited to focus on the bad books, especially when a book I hated may appeal to someone else. I don’t bother with resolutions, since I never go to any special effort to keep them. But 2012 was a watershed year for me, the year my novels went from computer files shared only with my critique partners to actual published books. Because the way I imagined that would work as of December 2011 turned out to be nothing like what actually happened, I decided to turn my last post of 2012 and my first of 2013 into a two-part retrospective/prospective on the state of publishing today. No more than anyone else can I tell where this wildly out-of-control car will careen over the next 12 months, but I can at least talk about what I experienced and what I anticipate for myself and for Five Directions Press.

This week, I tackle the ghosts of Christmas past. A year ago, this blog did not exist. I had heard of blogging; I even knew a couple of bloggers personally. But I had never considered blogging, still less blogging about books and technology, as a goal for myself.

My friend Diana Holquist, a published novelist, blogged. And in December 2011, Diana had just agonized her way through preparing a file for the Smashwords Meat Grinder and for CreateSpace and self-published her Battle Hymn of the Tiger Daughter. The book is a parenting memoir and very personal (although well worth reading!); she didn’t expect to sell many copies, so self-publishing made sense.

I listened and took mental notes, but I still thought in terms of traditional publishing. I had just finished my fourth draft of The Golden Lynx, and I was about to give the whole manuscript to my writers’ group to read. I had also, after six years of struggling, figured out a way to solve the underlying structural problem that had plagued The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel throughout its umpteen revisions. NESP had already gone through a full round of agent submissions without getting a bite, so I had doubts about the wisdom of sending it out again. Still, I thought that if I could find an agent for Lynx, the last set of revisions might be enough to push NESP, too, into the market.

So in January 2012, I began querying agents. Right away, I discovered that things had changed since my last foray into this arena. First, almost all submissions were electronic. Second, most agents no longer sent even a canned reply if they weren’t interested. In fact, as I soon found out, many agents require e-mailed submissions but rarely have time to read their e-mail—or receive so many e-mails that unless your query leaps out at them in the 90 seconds they have for you, forget it. So you can spend ten years writing and polishing a book, then three months researching an agent and preparing a good synopsis and query, only to have the entire package drop to the bottom of someone’s in box and never be seen again. (Believe me, I sympathize. I know what my in box looks like after four days away from my desk—sometimes after one day. The thought of facing 100 or more queries every single day would send me screaming from the room with my hands over my ears.)

In any case, for whatever reason, I did not find a literary agent willing to represent The Golden Lynx. The subject matter (Russia and its eastern neighbors in the time of Ivan the Terrible) may have seemed too obscure for mass-market publishers. The writing might still need work—although people who have read the novel, including those I don’t know personally, seem to find it entertaining, even compelling. Query letters and synopses are not my strength, so they may not have leaped as required. I may not have queried enough agents, or the right agents, or been lucky enough to hit the right agent on the right day at the right moment. And to be completely honest, one agent was still considering the full manuscript when I pulled the plug.

I pulled it because in those four months from January to May 2012, while I was revising NESP yet again, self-publishing/indie publishing surged from nascent trend to mainstream. “What can traditional publishing houses offer?” became a serious question. Compared to Amazon.com, Barnes and Noble, and Apple’s iBookstore, which let the author keep 65–70% of royalties on e-books—and even CreateSpace, where the author’s royalties are closer to 25–30% (4% on Expanded Distribution sales)—traditional publishing royalties combined with agents’ fees don’t look like much of a deal.

Of course, it’s not quite that simple, as I’ve explained in other posts. Self-publishing has costs, either in quality or for outside help. It demands skills that most authors don’t have. Publicity and marketing are the biggest bugbear. If you can’t get the word out, or you get it out by giving the book away for free, or the book isn’t up to snuff, high royalty rates don’t do you much good. Nor does the royalty system always work the way you might expect (see this post). Even so, the freedom to publish is a minor miracle. And as the months went by from January to May, the agent rejections came in (or no message arrived at all), and Diana’s self-published book sold, the prospect of self-publishing became more appealing. I decided to start with The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel and use it as a test case to see how the process worked.

From the beginning, quality mattered to me. I had ported NESP into Storyist, which exported ePub and Kindle files directly. As a result, creating an e-book was not a problem, although I later ran all my e-files through Folium Book Studio, because it gave me greater control and allowed me to purchase a low-cost ISBN for the electronic edition. Print didn’t scare me either: for the last 20 years, I’ve made my living copy editing and typesetting, and novels are the simplest thing in the world to typeset if you have the right software. Cover design was a rather more daunting prospect, but I had always known how I wanted the cover for NESP to look, so once I traversed the learning curve (especially the copyright issues), that worked out fine, too.

But I did want company on the journey. And the one thing that bothered me about self-publishing was the absence of gatekeepers. I have read quite a few self-published books that equal anything issued by traditional publishing houses. For every one of those, however, I’ve encountered half a dozen that, to be frank, could have used another few rounds of revision or editing or just someone to read the book for typos before it went to press. Don’t even get me started on book design, which has little relevance for e-books but is vital for print (on that topic, see “The Beauty of Books”).

Those concerns led to my biggest venture of 2012, the formation of Five Directions Press. I proposed it to my writers’ group in the spring, and they liked the idea. That was when I pulled Lynx from the agent, because it made little sense to start a press, only to hobble it by sending my best manuscript through another publisher. We spent a month or two working out the details and creating a website, and in June 2012 The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel appeared. Diana agreed to shift Battle Hymn to Five Directions Press in return for me typesetting her manuscript, and we reissued that book around Labor Day. Less than two weeks later, The Golden Lynx hit the virtual bookshelves, and the rest of my year has been spent trying to get the word out through various channels: giveaways, social networks, talks, person-to-person e-mails, interviews, and, above all, this blog. So far, sales have been slow but steady. I’ve sold more than 100 books—nowhere near J.K. Rowling territory but 100 more than this time last year. And because I indie-published, my books will remain in print while they build an audience, which I hope will expand in 2013.

But 2013 is for next week’s post. Check back to find out what I anticipate in “Ghosts of Christmas Future.”

Published on December 28, 2012 10:01