C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 55

December 6, 2013

Guilty Pleasures

I had a very intense week at work, so like most other people in that situation, I spent my off-hours doing anything but working. On Monday, I did manage an hour or two making minor revisions to The Winged Horse, but after that it was either work or total relaxation—nothing in between. Time for guilty pleasures.

I had a very intense week at work, so like most other people in that situation, I spent my off-hours doing anything but working. On Monday, I did manage an hour or two making minor revisions to The Winged Horse, but after that it was either work or total relaxation—nothing in between. Time for guilty pleasures.As those of you who have followed this blog know, one of my guilty pleasures is Sergei Bodrov’s 2005 film Nomad: The Warrior. I can even pretend it’s research for my novel, since it is set on the steppe: Kazakhstan in the 1700s, which is not too great a leap from a bit west of there in the 1500s. Another, recently discovered, is Kaoru Mori’s manga series A Bride’s Story. Set in various locations along the Silk Road in the early 19th century, it too lets me relax my brain while pretending that I’m—if not working—accumulating ideas for current and future stories.

The heroine of books 1 and 2, Amir, is a twenty-year-old semi-nomad married to the twelve-year-old resident of a provincial town. The age difference upsets many readers. It even bothers me: although I know it was common among the steppe peoples for brides to be a few years older than their grooms, eight years seems a bit much. Couldn’t the author have made her point with a heroine of eighteen and a hero of sixteen? Then, just as we are overcoming that problem and attaching ourselves to Amir and her young husband, Karluk, the series veers off to follow other characters, leaving Amir and Karluk to become bit players. The other stories have their own appeal, but still. There is also a rather annoying Englishman who seems to exist solely to justify the author's movement from place to place. But the basic story of Amir’s and Karluk’s arranged marriage and the considerations that cause Amir’s family to change its mind about the wedding after the fact is well told and compelling. The author claims at the end of book 5 that she plans to go back and follow Amir’s story from now on. I hope she does, perhaps including a few return visits to Talas, the tent-living widow featured in book 3.

But even when the stories are superficial, the art in these books is spectacular. The cover image shown above is just a small sample of their charm. Every book includes an examination of some aspect of Central Asian culture: carving, house building, embroidery, bread making, and more. The textiles, the clothing, the tent decorations, the hairstyles, the jewelry: these books are a novelist’s delight. They bring the past to life in a way that simple description, even deeply researched history, seldom can. If you want to see pre-conquest Central Asia in all its rich diversity and beauty, these books are a great place to start. Another set of Hidden Gems, for steppe fanatics everywhere.

Speaking of Hidden Gems, if you happen to see this post before December 8, 2013, Triskele Books is discounting most of its titles to 99 cents in a three-day promotion. Time to grab your copy of The Charter—and their many other titles!

Speaking of Hidden Gems, if you happen to see this post before December 8, 2013, Triskele Books is discounting most of its titles to 99 cents in a three-day promotion. Time to grab your copy of The Charter—and their many other titles!P.S. If you have not read manga before, you are not going crazy. The books really do read right to left. The image above therefore comes from the back cover, which is really the front.

Published on December 06, 2013 15:15

November 29, 2013

The Future of the Book?

Still spinning off my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview with Carol Strickland, I decided this week to chat about a point that came up near the end of our conversation: the future of the book.

As those who follow me know, I love printed books. Even so, I am an avid reader of novels on my iPad. In fact, I was an early adopter who treasured my Franklin Rocket e-reader until it died in my hands. I did read other people’s books on the Rocket—mostly classics, as I objected to paying for a format that might not (and in the end did not) survive. But I used it even more to relieve my guilt as a budding writer: instead of wasting “a lot of trees before I wrote anything good” (J.K. Rowling), I worked out my abysmal beginner’s efforts through stylus and e-ink.

I still read my own work on my iPad, both as e-books and, more effectively, as Storyist documents that I can edit. These e-books are not too different from the ones on my old Rocket—plain text on screen—although the backlit, full-color iPad screen makes the books much prettier than the Rocket ever could. The Eagle and the Swan, too, so far appears in the plain-text format. But the author and her publisher, Erudition Digital, are planning an enhanced version with images, history, links, perhaps video clips, and more. Is this, as they suggest, the future of the book? And if it is, should it be?

Don’t get me wrong. For The Eagle and the Swan, set in the barely known recesses of sixth-century Byzantine history, I think this is a fabulous idea. I’ve toyed with producing something similar—perhaps as a companion volume—for my Legends of the Five Directions series. At the moment, I’m using Pinterest to post images of sixteenth-century Russia and the peoples to its east and south, all of them as unfamiliar to most Westerners as Justinian and Theodora. But I have also produced the first version of a multimedia compilation with iBooks Author, which is easy to use (although you either have to sell the books exclusively through Apple or give them away for free—if I ever finish it, I’ll probably give away free copies to build interest in the series). There’s so much unfiltered information available that in cases like these, multimedia enhanced e-books are the perfect match.

But for any novel? There I’m not so sure. I bought Jack Kerouac’s On the Road as an enhanced e-book to get a glimpse of the concept. It was interesting. I admired it. But I found the links and the bells and the whistles so distracting that in the end I didn’t read the book. I was too busy clicking on this and that to get caught up in the novel’s world. It would drive me half-crazy if, in the middle of the mystery story I’m enjoying at this moment (J.J. Marsh’s Behind Closed Doors ), the book offered to show me maps of Zürich or images of what the characters were eating or a quick-and-dirty guide to DNA analysis. With Facebook, Google, and GoodReads a few taps away, achieving the sense of total immersion in an e-book is already more difficult than with paperback in hand.

So while I welcome enhanced e-books as an addition to plain text, I also hope that there will be ways to turn off the extra features or keep them apart from the story—as add-ons supplied in a separate file as part of the book purchase, maybe. At that moment when I realize the story has ended but I’m not yet ready to let go of the characters and move on, I would love to explore their world in more depth, guided by a knowledgeable author. But first I need a reason to care, which means that I need the author to pull me into the characters’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Whether the form is electronic or print, the traditional craft of fiction writing offers the best means to do that.

What do you think? Am I just behind the times?

As those who follow me know, I love printed books. Even so, I am an avid reader of novels on my iPad. In fact, I was an early adopter who treasured my Franklin Rocket e-reader until it died in my hands. I did read other people’s books on the Rocket—mostly classics, as I objected to paying for a format that might not (and in the end did not) survive. But I used it even more to relieve my guilt as a budding writer: instead of wasting “a lot of trees before I wrote anything good” (J.K. Rowling), I worked out my abysmal beginner’s efforts through stylus and e-ink.

I still read my own work on my iPad, both as e-books and, more effectively, as Storyist documents that I can edit. These e-books are not too different from the ones on my old Rocket—plain text on screen—although the backlit, full-color iPad screen makes the books much prettier than the Rocket ever could. The Eagle and the Swan, too, so far appears in the plain-text format. But the author and her publisher, Erudition Digital, are planning an enhanced version with images, history, links, perhaps video clips, and more. Is this, as they suggest, the future of the book? And if it is, should it be?

Don’t get me wrong. For The Eagle and the Swan, set in the barely known recesses of sixth-century Byzantine history, I think this is a fabulous idea. I’ve toyed with producing something similar—perhaps as a companion volume—for my Legends of the Five Directions series. At the moment, I’m using Pinterest to post images of sixteenth-century Russia and the peoples to its east and south, all of them as unfamiliar to most Westerners as Justinian and Theodora. But I have also produced the first version of a multimedia compilation with iBooks Author, which is easy to use (although you either have to sell the books exclusively through Apple or give them away for free—if I ever finish it, I’ll probably give away free copies to build interest in the series). There’s so much unfiltered information available that in cases like these, multimedia enhanced e-books are the perfect match.

But for any novel? There I’m not so sure. I bought Jack Kerouac’s On the Road as an enhanced e-book to get a glimpse of the concept. It was interesting. I admired it. But I found the links and the bells and the whistles so distracting that in the end I didn’t read the book. I was too busy clicking on this and that to get caught up in the novel’s world. It would drive me half-crazy if, in the middle of the mystery story I’m enjoying at this moment (J.J. Marsh’s Behind Closed Doors ), the book offered to show me maps of Zürich or images of what the characters were eating or a quick-and-dirty guide to DNA analysis. With Facebook, Google, and GoodReads a few taps away, achieving the sense of total immersion in an e-book is already more difficult than with paperback in hand.

So while I welcome enhanced e-books as an addition to plain text, I also hope that there will be ways to turn off the extra features or keep them apart from the story—as add-ons supplied in a separate file as part of the book purchase, maybe. At that moment when I realize the story has ended but I’m not yet ready to let go of the characters and move on, I would love to explore their world in more depth, guided by a knowledgeable author. But first I need a reason to care, which means that I need the author to pull me into the characters’ thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Whether the form is electronic or print, the traditional craft of fiction writing offers the best means to do that.

What do you think? Am I just behind the times?

Published on November 29, 2013 09:17

November 21, 2013

The Real Panem

I swear, it was pure coincidence that my interview this month on New Books in Historical Fiction happened to go live the same week as the release of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. I did have a vague sense that the film was due for release just before Thanksgiving, but it didn’t even occur to me until this morning, when I saw the review in the paper, that this blog post would go up on the day the film opened.

I swear, it was pure coincidence that my interview this month on New Books in Historical Fiction happened to go live the same week as the release of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. I did have a vague sense that the film was due for release just before Thanksgiving, but it didn’t even occur to me until this morning, when I saw the review in the paper, that this blog post would go up on the day the film opened.What makes it a coincidence is that this month I had the fun of interviewing Carol Strickland about her novel The Eagle and the Swan. The Eagle is Emperor Justinian I of Byzantium and the Swan his wife, Theodora—known in her youth, before she underwent a profound religious conversion, as the empire’s premier erotic dancer and courtesan, famous for her performance of “Leda and the Swan.” You can hear and, if you like, download the podcast at the link above.

When I read the book, I was struck by how Roman the world of Justinian and Theodora still was. This didn’t surprise me so much as give me a Doh! What did I expect? moment. Constantinople was (and remained) the head of the Eastern Roman Empire, and Justinian’s rule began in 527 CE—barely fifty years after the Fall of Rome. The novel starts a good ten years before that.

Justinian came from Thrace, born to a family of swineherds, raised to power through the military gifts of his uncle Justin, the illiterate general who preceded him on the imperial throne. He was the last emperor to grow up speaking Latin rather than Greek. Theodora spent her childhood in the circus, as a bear keeper’s daughter—and while not quite the arena where Katniss Everdeen fights for her life, this circus was not Barnum and Bailey/Ringling Brothers either. This was the circus of gladiators and chariot races, of Christians fed to lions, and the like. A large part of the book involves a protracted fight over the need to pacify the population with gifts, parades, and entertainment versus the need to fund the military campaigns that will (Justinian hopes) reunite the eastern and western halves of the shattered Roman Empire. Not to mention the popular unrest that follows when Justinian chooses power over pacification. Population management. Bread and circuses. Panem et circenses.

So listen to the interview. You may find out more than you expected from that long-ago, faraway world. And for some additional background on the author and what drew her to write Theodora’s story, I suggest checking out her “Personal Confession.” I discovered the post only after the interview, or we would have talked about it then. It’s a great story.

As usual, I wrote the rest of this post for the New Books in Historical Fiction site.

In 476 CE, according to the chronology most of us learned in school, the Roman Empire fell and the Dark Ages began. That’s how textbook chronologies work: one day you’re studying the Romans, and next day you’re deep in early feudal Europe, as if a fairy godmother had waved a magic wand.

Reality is more complex. The Fall of Rome affected only the western territories of that great world power, which had in fact been weakening for some time. The Eastern Roman Empire—later known as Byzantium or the Byzantine Empire—survived for another thousand years. Recast under Turkish rule as the Ottoman Empire, it lasted five hundred years more.

But the Eastern Roman Empire endured shocks and fissures of its own, and its survival was far from assured. Under the rule of Emperor Justinian I and his empress, Theodora, it entered a crucial phase. Justinian began life as a swineherd, Theodora as a bear keeper’s daughter, yet they fought their way to the pinnacle of power in Constantinople and, once there, established a new set of governing principles that for a while almost restored the empire that Rome had lost. Carol Strickland, in The Eagle and the Swan , traces the first part of Justinian’s and Theodora’s journey. Listen in as she takes us through the circuses, streets, brothels, monasteries, and churches of early sixth-century Byzantium, all the way to the imperial court.

Published on November 21, 2013 07:11

November 15, 2013

Long Shadows

It’s not easy being a new author. The barriers to traditional publishing loom large, from acquiring an agent to attracting a readership. Yet deciding to go it alone, or even with a group, leaves the struggling author swimming desperately upstream amid hungry fish in a school becoming larger by the day, even the hour. And since most authors have no experience with marketing, distinguishing oneself from the crowd easily becomes an exercise in frustration.

It’s not easy being a new author. The barriers to traditional publishing loom large, from acquiring an agent to attracting a readership. Yet deciding to go it alone, or even with a group, leaves the struggling author swimming desperately upstream amid hungry fish in a school becoming larger by the day, even the hour. And since most authors have no experience with marketing, distinguishing oneself from the crowd easily becomes an exercise in frustration. Yet the biggest problem with self-publishing is not the sheer number of books out there but the sad truth that so many of those books are poorly written, unedited, and abominably produced. Combine that with the aggressive spamming and shady tactics used by a few desperate authors, and you get a situation where many readers defend themselves by limiting their purchases to traditionally published books.

One can’t blame the readers—to an extent I do the same thing myself—but their caution does make life even harder for those of us who have put in the time and resources to learn to write, to edit our work, and to produce books that are as appealing as we can make them. I know this from personal experience. So while this blog of mine is by no means focused on book reviews, I do like, once in a while, to give a shout out on behalf of other self- or coop- or small-press-published authors who have done their part and created books that can give the bestsellers a run for their money—not in numbers, perhaps, but in quality. Authors like Gillian Hamer, whose historical/contemporary mystery The Charter I finished last night and thoroughly enjoyed.

The Charter traces the long shadows cast by a shipwreck off the coast of Anglesey, Wales, in October 1859. It begins with the crash of the Royal Charter, a ship traveling from Australia to Liverpool filled with gold miners returning home with their riches. When the boat runs aground on a reef, the miners, convinced that their wives and children will be rescued first, load them down with gold. But the boat sinks before the crew can lower the lifeboats, and the women and children, weighted down with treasure, go straight to the bottom. The treasure is never found—or is it? No one is talking, but here and there local farmers seem to have, all of a sudden, lots of money to spend. As a result, families squabble. When, 150 years later, Sarah Morton is called back to the region for her father’s funeral, the repercussions of this tragedy are still felt in the region as bursts of hostility that from time to time explode in murder. Within a few chapters, Sarah becomes convinced that her father is one victim in this ongoing series of crimes.

Hamer can write—and how. Her scenes dump the reader right into the moment. See, for example, the end of her preface, which sets up the tragedy of 1859:

The Royal Charter—the steamship that has carried my family from Hobson’s Bay, Australia to a “better life” in England—is still being pounded by the storm. With every massive wave that crashes over her, I expect the ship to disappear, but after each surge of the tide she reappears, as if trapped by the jagged rocks and unable to find release.

Bodies pulled and tossed by the furious tide, pushed inland one minute and dragged back into the white foam the next. Men I’d seen issuing orders; women I’d spoken to; children I’d spent many hours with over the past weeks. I close my ears to the screams and cries that circle my head like squawking gulls.

I stand there for seconds, minutes, hours, days … I know not.

The spray of the ocean is on my face. I hear the roar in my ears. I taste the salt on my lips.

But I know it cannot be. I know this cannot be real. The truth hits me. Bile fills my mouth; I double over and retch.

When I straighten, I stand in silence and calmness. The storm still rages all around me, but I am protected. As if in the eye of the hurricane, my own space is quiet and still.

The answer is suddenly clear.

My name is Angelina Stewart.

I am eleven years old.

And I am dead.

This is good stuff, and despite the occasional glitch that a professional editor would have caught (or not, since editing even at big publishers is not what it used to be)—such as a character who appears to arrive on an island despite having no boat—the book kept me wholly focused on Sarah and her drive to keep herself and her unborn baby alive long enough to solve the mystery of what happened to the Royal Charter’s gold. Hamer produces enough twists in the plot to keep me guessing and to take me by surprise at the end—in the good way, where the solution makes sense even though I didn’t see it coming—and most of all, she doesn’t forget her characters. Each one is distinct and well-rounded; the right ones are likable (or unlikable); and Sarah grows in a thoroughly believable way. The sense of immersion in the Welsh coast and its changing seasons is intense. So check out The Charter. It’s not expensive, and it’s well worth your time.

Hamer has two other novels, Closure and Complicit, which I can’t wait to read. She is also a member of Triskele Books, a writers’ cooperative in the UK that I have mentioned before. Five Directions Press uses a similar business model to Triskele, but otherwise we are linked only by a sense of comradeship. Triskele has just published an account of its journey to publication, The Triskele Trail, which I may explore in more depth in a future post. You can find out more about them and about Gillian Hamer, including links to purchase her books, at their website. She sent me a free e-book copy of The Charter in return for my honest review.

Published on November 15, 2013 13:47

November 8, 2013

Earthly Paradises

I read with great interest Lisa Yarde’s post at Unusual Historicals, “Plants and Their Properties: Moorish Perspectives,” which inspired me this week (thank you, Lisa!). Her discussion of the importance of plants and fountains in palaces like the Alhambra reminds me of the reaction that Nasan, my heroine in The Golden Lynx, has when she first sees her new home in Moscow. In brief, she looks around and thinks, “Where are the fountains? Where are the courtyards and the plants?”

Nasan has spent the last two years in the khan’s palace at Kasimov. Even though that building has not survived, we know a bit about it from descriptions and reconstructions. We can assume, based on similar complexes in Bakhchisarai in Crimea and elsewhere, that it was built according to the same principles Yarde describes as having been used in Moorish Spain.

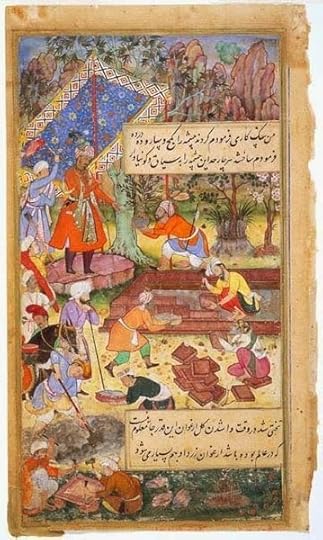

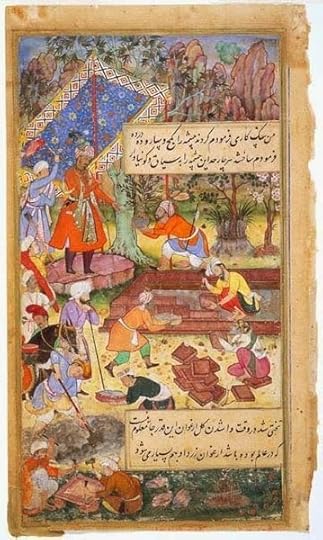

Nasan herself later summarizes these principles, again in contrast to what she sees before her in the Russian court: “Although richly decorated, the palace lacked the harmony of Muslim architecture—its lightness, its grace, its perfect proportions. Here no opaline swirls of marble refracted with lunar subtlety the rays that pierced filigreed walls, no turquoise tiles glowed more intensely blue than the sky above them, no looping black-dotted calligraphy captioned brilliant miniatures of everyday life” (392). The buildings she has in mind consist of interlocking courtyards edged with rooms and terraced passageways, each with its pools, fountains, and elaborately planned, mathematically precise gardens—a style that characterized the Tatar khanates of Central Asia and the Mughal palaces of India just as much as those of al-Andalus and Istanbul. The founder of the Mughal dynasty, Babur the Tiger—himself a Tatar prince of Central Asia—was so devoted to his gardens that he decreed his own burial in his favorite, located near Kabul. And there he lies to this day.

Russians had gardens, of course. Every urban estate had a place to grow vegetables and herbs for cooking, a pond for ducks and geese, an orchard. The Russian use of space was so extensive that foreign visitors assumed the population of Moscow to be ten times as high as it was in reality (although the tendency of medieval and early modern people to grossly overestimate numbers may also play a role here). But until the Europeanization of the eighteenth century, Russian gardens tended to serve a practical purpose. Tatar gardens existed for pleasure, for spiritual nourishment, for repose, and as reminders of the blessed gardens of Paradise. Islam, a religion born in the deserts of Arabia, had (and has) great respect for the power of water to bring life from the earth.

The irony here is that the Tatars were people not of the desert but of the steppe, nomadic pastoralists who for centuries had subsisted mostly on meat and milk products. The herds fed on grass; people fed on the herds. The vast expanses of the Eurasian grasslands discouraged the intensive cultivation required to maintain gardens, restricting these earthly paradises to the few cities large enough to attract the attentions of a descendant of Genghis bent on self-aggrandizement.

Then again, nature on the steppe has its own wild beauty. Perhaps the flowers and fountains of Paradise spoke with a special power to former nomads wooed into settling down yet still yearning in their hearts for the untrammeled life they had abandoned. We can’t know, but we can imagine. That’s the fun of writing fiction.

Nasan has spent the last two years in the khan’s palace at Kasimov. Even though that building has not survived, we know a bit about it from descriptions and reconstructions. We can assume, based on similar complexes in Bakhchisarai in Crimea and elsewhere, that it was built according to the same principles Yarde describes as having been used in Moorish Spain.

Nasan herself later summarizes these principles, again in contrast to what she sees before her in the Russian court: “Although richly decorated, the palace lacked the harmony of Muslim architecture—its lightness, its grace, its perfect proportions. Here no opaline swirls of marble refracted with lunar subtlety the rays that pierced filigreed walls, no turquoise tiles glowed more intensely blue than the sky above them, no looping black-dotted calligraphy captioned brilliant miniatures of everyday life” (392). The buildings she has in mind consist of interlocking courtyards edged with rooms and terraced passageways, each with its pools, fountains, and elaborately planned, mathematically precise gardens—a style that characterized the Tatar khanates of Central Asia and the Mughal palaces of India just as much as those of al-Andalus and Istanbul. The founder of the Mughal dynasty, Babur the Tiger—himself a Tatar prince of Central Asia—was so devoted to his gardens that he decreed his own burial in his favorite, located near Kabul. And there he lies to this day.

Russians had gardens, of course. Every urban estate had a place to grow vegetables and herbs for cooking, a pond for ducks and geese, an orchard. The Russian use of space was so extensive that foreign visitors assumed the population of Moscow to be ten times as high as it was in reality (although the tendency of medieval and early modern people to grossly overestimate numbers may also play a role here). But until the Europeanization of the eighteenth century, Russian gardens tended to serve a practical purpose. Tatar gardens existed for pleasure, for spiritual nourishment, for repose, and as reminders of the blessed gardens of Paradise. Islam, a religion born in the deserts of Arabia, had (and has) great respect for the power of water to bring life from the earth.

The irony here is that the Tatars were people not of the desert but of the steppe, nomadic pastoralists who for centuries had subsisted mostly on meat and milk products. The herds fed on grass; people fed on the herds. The vast expanses of the Eurasian grasslands discouraged the intensive cultivation required to maintain gardens, restricting these earthly paradises to the few cities large enough to attract the attentions of a descendant of Genghis bent on self-aggrandizement.

Then again, nature on the steppe has its own wild beauty. Perhaps the flowers and fountains of Paradise spoke with a special power to former nomads wooed into settling down yet still yearning in their hearts for the untrammeled life they had abandoned. We can’t know, but we can imagine. That’s the fun of writing fiction.

Published on November 08, 2013 09:07

November 1, 2013

The Press Kit

Sometime ago—the spring of 2013, I think—I read a recommendation that every writer should include on his/her website a tab for the media. Unfortunately, I no longer remember the source, but in any case, the idea was to put in one place, clearly labeled as “Media” or “Press,” the information that reporters might need: author bio and picture, book descriptions, reviews—in short, a press kit. The advice suggested putting the information in both readable format on the web page and in PDF format for download.

Sometime ago—the spring of 2013, I think—I read a recommendation that every writer should include on his/her website a tab for the media. Unfortunately, I no longer remember the source, but in any case, the idea was to put in one place, clearly labeled as “Media” or “Press,” the information that reporters might need: author bio and picture, book descriptions, reviews—in short, a press kit. The advice suggested putting the information in both readable format on the web page and in PDF format for download.Even though my books, published by a small press, had made so little splash in the media that preparing a press kit seemed like hubris, I figured a media page with information on me and my books couldn’t hurt. Alas, I had never seen a press kit. I put together the information in a single document that ran about 15 pages.

Luckily for me, no one downloaded it. But on the off-chance that some of my readers may never have seen a press kit either, I thought this post might prove useful. Even traditionally published authors are asked to provide information for their own press kits, although they can expect to receive more guidance than I did.

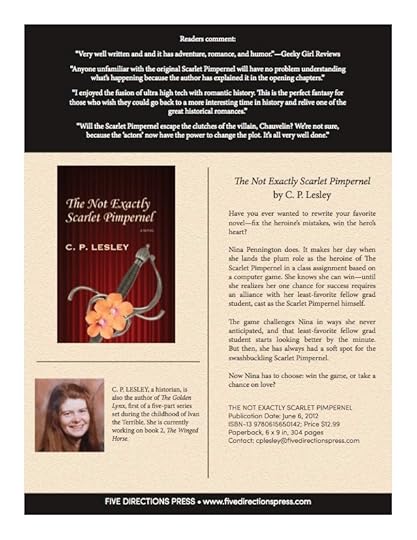

My woeful ignorance changed when I became the host of New Books in Historical Fiction. Publicists began sending me press kits together with review copies of the books whose authors I planned to interview. After a while, it dawned on me that I could use these as models to spiff up my own miserable efforts, a task now mostly complete. So what did I learn? What is a press kit? I’ll use the one I created for The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel as an example (but keep in mind that others may—and probably do—have a better grasp of the form than I do).

First off, a press kit is a single page, printed on both sides, or at most three pieces of paper. It focuses on one book. Typically, it starts off with quotations from reviews—the more prestigious the issuing publication, the better. In my case, because my publisher is so small, I used one- or two-sentence excerpts from reader reviews, chosen to give the widest sense of the story’s tone and impact.

The next most important element is the book cover and information. I chose to run these side by side, in a template that I am developing for all the Five Directions Press books. The book information includes the title and author’s name, the blurb from the back, the publication date, ISBN, price, format, number of pages, and contact information for me and for the press.

Then we have information about the author, including a picture, which often appears on the back of page 1. Since I am a relatively unknown author, I kept this short and put it on the front, then used the other side to give some background information on why I wrote this book. For The Golden Lynx, I used the same format but provided historical information on the entire series.

And that’s it. If your book has won awards, add them to the first page and move the author’s information to the reverse side. If you have many books reviewed in important places, you can add a second page to cover the gamut of your literary fame. If your book relies on specialized knowledge—understanding agoraphobia, the cultural climate of eighth-century Central Asia, what led to Zelda Fitzgerald’s confinement to an insane asylum—you may want to add a second or third page to convey the basics, so that a reporter need not look them up. But keep it short. And the fewer credentials you have, the more modest the press kit needs to be. Only comedians want to leave journalists laughing hysterically at their claims.

As always, it pays to edit, edit, edit and to find someone who can put a bit of thought into the design—and who owns the software that makes that design look professional. But the good news is that the press kit is much easier to produce than I originally thought. You probably have all the information in various marketing materials. My discussions on the back came from the mini-essays I wrote to fill in the review space for my books on GoodReads.

So go for it. It’s not difficult. And if the press does knock on your door. You’ll be ready.

If you’d like to see more, you can find the press kits on my website.

Published on November 01, 2013 06:55

October 25, 2013

Cultures of Eternity

The Last Shaman of the Oruqen

The Last Shaman of the OruqenPublic domain photograph

by Richard Noll, 1994

Last week’s interview with Yangsze Choo got me thinking. Not to give away any spoilers—much of what she describes in The Ghost Bride is her own invention—in the interview she mentions that the family remains the basic unit in the Chinese afterlife just as it does in Chinese culture. Ghosts depend on their families for money, food, housing, clothing, luxuries—all the essentials, burned in greater or lesser quantities by surviving relatives to indicate their devotion or their affluence or both. People who die outside that family structure become “hungry ghosts,” miserable creatures who wander unfed and poorly clothed through the afterlife except once a year, when the community gets together and burns offerings for them.

Tatar ghosts, too, belong to communities based on blood ties. Nowadays, most Tatars profess one of the world’s major religions (Buddhism, Islam, or Christianity, for the most part) or an atheism adopted during the seven decades of Soviet rule. Older customs survive, such as tying strips of fabric to lone-standing trees in supplication, but the main religious impulse lies elsewhere.

In the sixteenth century, though—the time depicted in my Legends of the Five Directions series—the sense of a multigenerational community comprising ancestors, current family members, and those yet to be born remained all-pervasive. Although the dead existed on a plane separate from the living, shamans could visit them. The ancestors could interfere in the lives of their descendants—to influence, warn, or protect. They guaranteed victory in battle, assisted in childbirth, and welcomed those who lost their struggles with enemies or disease. “By God and my ancestors,” was the oath sworn by warriors. The system of support supplied by the living seems to have operated more informally than the equivalent system in China, but it formed an essential and frequent element of daily life. Nomads tossed ladles of milk to honor the ancestors and fed them through grease dropped into the hearth fire or rubbed on the mouths of the wooden spirit dolls who represented the grandmother guardians. Decisions—whether political, economic, religious, or personal—took place within that larger community constituted by the dead and the living working (ideally) in harmony.

Western ghosts, in contrast, almost invariably haunt as individuals. The Celts, once a steppe people, do retain a sense of the dead as occupying a separate level of existence on the other side of a curtain that sometimes thins enough to cross. Hallowe’en, which we celebrate next week, is the much-diluted version of the ancient Celtic holiday of Samhain (pron. Sav-in or Sow-ain, depending on whether you are Scots or Irish). On the night before the New Year, ghosts were believed to cross into the realm of the living, who had to guard themselves against this incursion. Today we protect ourselves from small children in fancy costumes who can be bought off with candy.

But the more usual Western ghost is not part of a horde, spiritual or otherwise. The abandoned lover who cannot let go, the monk who opposed the dissolution of his monastery, the captain of the ship who met an untimely end—these are Western ghosts. Their tragedies are individual, and they must be laid as individuals. We have no communal ritual to feed, honor, or appease them. Most of the time, we don’t believe they exist: what more shattering fate for a poor ghost can a society conjure up?

One system is not better or worse than another. The Western emphasis on the individual lies at the heart of our dedication to human rights and the value of every life as well as a “pull yourself up by your own bootstraps” philosophy. The Eurasian embrace of community supports those within the group even as it constricts their choices to those approved by the group. Moreover, the two systems overlap, and neither is perfect or complete. Other places in the world have their own views of the afterlife, their own mixes of individuality and collectivism.

But one thing is certain: the rules of life here on earth, however our own community defines them, do not end here. They bind us for eternity.

Published on October 25, 2013 08:12

October 18, 2013

Raising Ghosts

I love tales of the afterlife. Why, I’m not exactly sure. The reassurance that there might be an afterlife certainly plays a part, but I have never liked horror stories—not even the yarns about ghosts told by kids around the campfire to ensure no one sleeps that night. I’m a sucker, though, for books about near death experiences, lives between lives, past-life regressions, and well-imagined other worlds that just happen to be populated by dead people. (Let me note that I don’t believe everything I read; what I enjoy is the fantasy element: if there were an afterlife, what would it be like?)

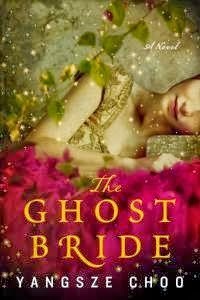

I love tales of the afterlife. Why, I’m not exactly sure. The reassurance that there might be an afterlife certainly plays a part, but I have never liked horror stories—not even the yarns about ghosts told by kids around the campfire to ensure no one sleeps that night. I’m a sucker, though, for books about near death experiences, lives between lives, past-life regressions, and well-imagined other worlds that just happen to be populated by dead people. (Let me note that I don’t believe everything I read; what I enjoy is the fantasy element: if there were an afterlife, what would it be like?)So you can imagine how delighted I was to run across Yangsze Choo’s stunning debut novel, The Ghost Bride. I couldn’t wait to sign her up for an interview. We had our conversation yesterday, and I discovered that it’s even more fun to chat with her in person than to read her book. You can hear the results at New Books in Historical Fiction. As always, these podcasts are available free of charge.

Not surprisingly, we talk at length about the Chinese view of the afterlife, as filtered through Yangsze’s imagination. But we also talk about writing and women’s roles and (I kid you not) the Car Talk guys on NPR. So even if you’re not as crazy about imagined afterlives as I am, go ahead and give it a listen.

The rest of this post comes from the interview page.

Malaya, 1893. Pan Li Lan, a beautiful eighteen-year-old, has watched her Chinese merchant family decline since the death of her mother from smallpox during Li Lan’s early childhood. Her father lives in isolation and smokes too much opium: bad for business, as anyone can see from the decaying surroundings of their Malacca estate.

Li Lan knows that her prospects of finding a husband are poor. Still, she does not expect her father to offer a dead man as bridegroom—even one whose family promises to keep her in luxury for the rest of her life. When Li Lan’s would-be husband begins to haunt her dreams—and she falls for his cousin in reality—her desperation to escape leads her on a journey through the Chinese afterlife, searching for the key that will free her from a marriage she dreads. But she slowly realizes that to succeed, she must uncover the secrets of her past … and her prospective groom’s.

The Ghost Bride opens a window on a fascinating and little-known world in which a spunky young woman tests the boundaries of her traditional middle-class existence in pursuit of a better future. Yangsze Choo brings Li Lan and her family to vivid life, then spins them off into a mirror society with rules eerily familiar yet utterly strange. It’s a journey well worth taking.

Published on October 18, 2013 10:22

October 11, 2013

Slowing Down

Don’t ask me how I contracted pertussis, better known as whooping cough. No one I know has it, so I must have picked it up in some public place. Apparently it’s highly contagious, and like a lot of diseases of that type, it’s most contagious before you know you have it, in the initial stage when it seems like a cold—and a baby cold at that.

The whole thing came as a big surprise to me, not least because I had whooping cough as a child. I don’t remember it myself, but my mother got to nurse two kids under the age of five through the disease at the same time, so you can bet she remembers. I just assumed it was like measles and mumps, and once you survived the first round, you were set for life.

Then the whooping started. The first time was at dinner, and I thought I'd choked on a bit of lettuce. The second time, at 4 am, I had to face the possibility that this wasn’t an accident. I called the doctor the next morning, and by noon I had a prescription for amoxicillin. Which seems to be working, if slowly.

Problem is, I don’t do illness well. As one of my fellow editors once noted, “You have a great deal of energy.” At the time I thought she meant “man, you’re a pain,” because I had been lobbing issues at her like a demented monkey pitching coconuts (I later found out she meant it as a compliment), but either way, I had to admit she was right. Under normal circumstances, I do have a great deal of energy. I come from a long line of women who kept their households running despite the dozen kids and the herring going south when they should have gone north and the darned boat springing a leak right when it was supposed to put out to sea. In my day job I coordinate the work of a flock of editors while riding herd on fifteen to twenty authors at a time and waiting for the day to wrap up so I can start in on my research or my novel of the moment. That’s when I’m not updating this blog, working on my website, or doing my bit for Five Directions Press. When I read about Victorian heroines who slip gracefully into a decline, my natural instinct is to administer a swift kick in the pants and advice to get up and get moving. Who has time to be sick?

All of which may explain why, once in a while, my body decides to administer a swift kick in the pants to me and force me to slow down. As with pertussis.

I’m sure this is good for me. Really. But if you happen to see any of those wooden stress balls, like the ones Charles Laughton used to play Captain Bligh on Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), send them my way, okay?

Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

The whole thing came as a big surprise to me, not least because I had whooping cough as a child. I don’t remember it myself, but my mother got to nurse two kids under the age of five through the disease at the same time, so you can bet she remembers. I just assumed it was like measles and mumps, and once you survived the first round, you were set for life.

Then the whooping started. The first time was at dinner, and I thought I'd choked on a bit of lettuce. The second time, at 4 am, I had to face the possibility that this wasn’t an accident. I called the doctor the next morning, and by noon I had a prescription for amoxicillin. Which seems to be working, if slowly.

Problem is, I don’t do illness well. As one of my fellow editors once noted, “You have a great deal of energy.” At the time I thought she meant “man, you’re a pain,” because I had been lobbing issues at her like a demented monkey pitching coconuts (I later found out she meant it as a compliment), but either way, I had to admit she was right. Under normal circumstances, I do have a great deal of energy. I come from a long line of women who kept their households running despite the dozen kids and the herring going south when they should have gone north and the darned boat springing a leak right when it was supposed to put out to sea. In my day job I coordinate the work of a flock of editors while riding herd on fifteen to twenty authors at a time and waiting for the day to wrap up so I can start in on my research or my novel of the moment. That’s when I’m not updating this blog, working on my website, or doing my bit for Five Directions Press. When I read about Victorian heroines who slip gracefully into a decline, my natural instinct is to administer a swift kick in the pants and advice to get up and get moving. Who has time to be sick?

All of which may explain why, once in a while, my body decides to administer a swift kick in the pants to me and force me to slow down. As with pertussis.

I’m sure this is good for me. Really. But if you happen to see any of those wooden stress balls, like the ones Charles Laughton used to play Captain Bligh on Mutiny on the Bounty (1935), send them my way, okay?

Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)

Published on October 11, 2013 12:13

October 4, 2013

Blogging Books

I haven’t paid much attention to technology this year, focusing instead on publishing, podcasts, and—most of all—history. I stopped because I no longer had much to say. By now, I can get around Facebook, GoodReads, Tumblr, Pinterest, even Twitter—although I’m far from mastering any of them. Since I don’t aspire to the status of social media guru, the basics seem like enough.

I haven’t paid much attention to technology this year, focusing instead on publishing, podcasts, and—most of all—history. I stopped because I no longer had much to say. By now, I can get around Facebook, GoodReads, Tumblr, Pinterest, even Twitter—although I’m far from mastering any of them. Since I don’t aspire to the status of social media guru, the basics seem like enough. But this week I joined a new site, BookLikes, devoted entirely to blogging about books. So I am back to reading help files, instructions, usage policies, and FAQs while puzzling over this feature or that and wondering how best to take advantage of this new service. I’ll talk about BookLikes itself in a moment. It’s a nice site—run out of Poland, near as I can tell, and launched only in May 2013. But first, why did I join? Am I addicted to social media? Cursed with the attention span of a butterfly? A glutton for punishment?

Xü Xi, Butterfly and Wisteria (970 AD)

Xü Xi, Butterfly and Wisteria (970 AD)Source: Wikimedia Commons

This picture is in the public domain

in the United States because of its age.

None of the above (I hope—the butterfly charge sometimes seems all too apt). The journey that led to BookLikes started on GoodReads. About two weeks ago, GoodReads announced that it had changed its terms of service to prohibit shelves, groups, and even reviews that focused primarily on authors’ behavior rather than their books. Its staff had already deleted some groups and shelves and would continue to check members’ content and remove any that violated the new terms of service. Five thousand messages and counting protested this decision and the way the staff communicated and implemented it.

This is not the place to discuss the ins and outs of the policy shift, on which I have mixed feelings. I did not join GoodReads to promote my books; at the time, I didn’t know that was possible. I joined because a fellow editor suggested it as a good place to find book recommendations. After joining, I did set up an author profile and claim my books; I have participated in giveaways and group reads, including one of my Golden Lynx; and I have joined a number of groups, taking care to read and observe the rules. I enjoy talking with readers—and with other writers, if they want to discuss books or writing rather than relentlessly promote. And on GoodReads as elsewhere, I try always to remain professional, which means never attacking or insulting anyone. So the change in GoodReads policy does not affect me personally. I will maintain my presence there even as I move (most of) my books and reviews to BookLikes.

The decision to move has less to do with GoodReads itself than with a recognition that the site may be over-saturated at this point: too many self-promoting authors, too many members in a plethora of groups too vast to track, too much corporate patronage. A small, emerging site seems worth exploring as an alternative or complement to the big, well-established one. Yes, BookLikes, if it succeeds, may one day be snapped up by a mega-corporation and develop the same problems that affect GoodReads. But that day is not yet, and if it happens, I can move on. In the meantime, I rather like the idea of being present at the beginning of something rather than jumping on midway.

So what is BookLikes? At its heart, it is a blogging site focused on books. If you have used Tumblr, you will recognize the interface. Each user who registers for a free account receives a personal site that includes a blog, which that user can use to review books, report progress on challenges, and comment on whatever s/he pleases. You can follow people (and block those who misbehave), as well as like and comment on others’ posts. You have bookshelves, which you can import from various other places, add to, and edit. You can synchronize with GoodReads, Facebook, and Twitter if you like your social media working together—or keep them separate if you don’t. You can customize your blog template and add pages to it. BookLikes verifies author, publisher, and bookseller accounts and assigns them a green checkmark that confers certain privileges. The staff seems a bit overwhelmed at the moment by a massive influx of new members, so the verification does not happen instantaneously, but that’s understandable.

The one thing that is missing so far is groups, although these are supposed to be on their way. There is a certain geeky quality to the customization, which includes editing HTML, a frightening prospect for the likes of me. Fortunately, the early adopters have written helpful tutorials, although I have yet to figure out why my custom-designed wallpaper, which looks lovely on a computer browser, moves to obscure the page list when viewed on a tablet. The import of my books, shelves, and reviews went smoothly, though, and the site is on the whole easy to use and remarkably polished for a place that has spent only five months in the public eye. You can follow me there as cplesley.

Published on October 04, 2013 12:02