C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 60

December 21, 2012

Both Sides of the Author Interview

Despite my technological challenges, I did succeed in re-recording (and not mucking up) my interview with Karen Engelmann about her novel The Stockholm Octavo, its origins, its themes, the importance of folding fans and cartomancy, the French and (stillborn) Swedish revolutions, and much more. You can find the results at New Books in Historical Fiction. You already know that I think her book is spectacular, but you should also know that she speaks very well. She’s informative and focused, and it was a joy to interview her.

Here is the short description of The Stockholm Octavo that I wrote for NBHF:

KAREN ENGELMANN

The Stockholm Octavo

ECCO BOOKS, 2012

by C. P. LESLEY on DECEMBER 20, 2012

It’s 1789, and despite the troubles in France, Emil Larsson, a sekretaire in the Customs Office in Stockholm, has life pretty much where he wants it. His job brings him lucrative under-the-table deals with pirates, smugglers, and innkeepers—not to mention a dashing red cape that appeals to the ladies—and he has managed to parlay his skill as a gambler into a partnership with the mysterious Mrs. Sparrow, owner of a prestigious private club dedicated to games of chance.

But when the head of the Customs Office announces that every sekretaire must marry if he wishes to keep his post, Emil sees his carefree existence slipping away. Mrs. Sparrow offers to help by casting an octavo—a set of eight predictive cards representing key figures whom Emil must identify and manipulate to achieve his predicted future of love and connection. As Emil moves about the Town (Stockholm), every encounter assumes new meaning. Is this his Prisoner? His Key? His Courier?

We don’t know, and neither does he. But as Emil’s quest continues, the stakes rise. The situation in France deteriorates; and the future of the Swedish monarchy and its king, Gustav III, increasingly hinges on Emil’s ability to decipher his octavo and influence the contest between Mrs. Sparrow and the fascinating Uzanne—mistress of the fan, foe of the king, and the person most likely to prevent Emil from attaining his goals.

Fans of historical mystery and political intrigue will love Karen Engelmann’s “irresistible cipher between two covers—an atmospheric tale of many rogues and a few innocents gambling on politics and romance in the cold, cruel north”—as Susann Cokal characterizes The Stockholm Octavo (ecco Books, 2012) in the New York Times Book Review (December 9, 2012).

The link to subscribe to this and future podcasts in New Books in Historical Fiction via iTunes now works, as does the RSS feed subscription. And like us on Facebook to get updates there, too. We don’t yet have an independent presence on Twitter, but following the New Books Network will pick up our posts.

Interviewing Karen was a lot of fun, but I also participated in an author interview as the author this week. Diane Vanaskie Mulligan, the talented YA author of Watch Me Disappear, has been interviewing indie authors on her blog. These are written interviews, not podcasts. You can find mine at this address, but also check out the other entries and Diane’s own book. I can vouch for its being very well written!

I wish you all a wonderful holiday season as I get ready to celebrate Christmas with my family (and make as much progress as possible on The Winged Horse during my lovely eleven days off). I’m not going away; I will probably post next Friday, but family comes first.

Merry Christmas, Happy New Year, and Season's Greetings to all, whatever celebration you choose!

Here is the short description of The Stockholm Octavo that I wrote for NBHF:

KAREN ENGELMANN

The Stockholm Octavo

ECCO BOOKS, 2012

by C. P. LESLEY on DECEMBER 20, 2012

It’s 1789, and despite the troubles in France, Emil Larsson, a sekretaire in the Customs Office in Stockholm, has life pretty much where he wants it. His job brings him lucrative under-the-table deals with pirates, smugglers, and innkeepers—not to mention a dashing red cape that appeals to the ladies—and he has managed to parlay his skill as a gambler into a partnership with the mysterious Mrs. Sparrow, owner of a prestigious private club dedicated to games of chance.

But when the head of the Customs Office announces that every sekretaire must marry if he wishes to keep his post, Emil sees his carefree existence slipping away. Mrs. Sparrow offers to help by casting an octavo—a set of eight predictive cards representing key figures whom Emil must identify and manipulate to achieve his predicted future of love and connection. As Emil moves about the Town (Stockholm), every encounter assumes new meaning. Is this his Prisoner? His Key? His Courier?

We don’t know, and neither does he. But as Emil’s quest continues, the stakes rise. The situation in France deteriorates; and the future of the Swedish monarchy and its king, Gustav III, increasingly hinges on Emil’s ability to decipher his octavo and influence the contest between Mrs. Sparrow and the fascinating Uzanne—mistress of the fan, foe of the king, and the person most likely to prevent Emil from attaining his goals.

Fans of historical mystery and political intrigue will love Karen Engelmann’s “irresistible cipher between two covers—an atmospheric tale of many rogues and a few innocents gambling on politics and romance in the cold, cruel north”—as Susann Cokal characterizes The Stockholm Octavo (ecco Books, 2012) in the New York Times Book Review (December 9, 2012).

The link to subscribe to this and future podcasts in New Books in Historical Fiction via iTunes now works, as does the RSS feed subscription. And like us on Facebook to get updates there, too. We don’t yet have an independent presence on Twitter, but following the New Books Network will pick up our posts.

Interviewing Karen was a lot of fun, but I also participated in an author interview as the author this week. Diane Vanaskie Mulligan, the talented YA author of Watch Me Disappear, has been interviewing indie authors on her blog. These are written interviews, not podcasts. You can find mine at this address, but also check out the other entries and Diane’s own book. I can vouch for its being very well written!

I wish you all a wonderful holiday season as I get ready to celebrate Christmas with my family (and make as much progress as possible on The Winged Horse during my lovely eleven days off). I’m not going away; I will probably post next Friday, but family comes first.

Merry Christmas, Happy New Year, and Season's Greetings to all, whatever celebration you choose!

Published on December 21, 2012 13:28

December 14, 2012

Less Than Perfect

If you had asked me just yesterday, I would have sworn that I had a healthy respect for my own limitations. I copy edit and typeset for a living, and I've learned the hard way that no matter how diligently I read proofs, somehow, somewhere, an error will slip through. Big errors, small errors, errors I can't believe I missed: there's always something. As my (work) publisher once put it, “Nothing clarifies the mind [making it possible to see mistakes] like the knowledge it's too late to change things.”

As if editing were not enough, my relaxation method of choice is classical ballet. I took class as a small child and went back to it only in my late twenties. As a result, I have no illusions that I will ever dance well. For a long time, I continued to get better, and that kept me going. But classical ballet is an unforgiving discipline: even the best dancers strive in vain to achieve perfection; and in time, the body rebels. The knowledge remains, but the ability to attain the goal slowly declines.

My other hobby, writing fiction, also came to me in midlife and required long years of beating my head against a wall trying to improve without fully understanding what improvement required. I've heard it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master any skill, and I have the experience to prove it: ten years of ballet to go from klutz to not-so-awful; ten years of fiction writing before I hit my stride. The editing is harder to measure, because I'm not sure exactly when I went from newbie to pro, but I've been comfortable with it for at least half of my almost two decades on the job.

So why I thought I could conquer the mysteries of audio capture software in a couple of interviews escapes me. Even so, when I finished an absolutely wonderful conversation with Karen Engelmann, author of The Stockholm Octavo—which I highly recommend (as do the New York Times Book Review and the Indie Book Awards, among others)—only to discover that for reasons that remain cloudy the software had captured my voice but not hers, I was livid. I don't mean quiet, ladylike annoyed. I mean pounding on the floor, take a drive in the car so I could scream without upsetting Sir Percy and the cats infuriated. Such a wonderful conversation! Such a great interview! And no one would ever hear it except me.

I'm sure that whatever the problem was, it came about through user error. Yes, it seems absurd to me, a regular person, that after I told the software program to call up Skype and record what it heard, its default position caused it to save only what came in through the microphone and not the person at the other end of the call. But if I had a better sense of what I was doing, I could have recognized the problem and fixed it before I wasted 45 minutes of Karen's time. Alas, that didn't happen.

The good news is that she's still talking to me. If I practice over the weekend, I should have a new interview up at New Books in Historical Fiction by the end of next week. Julian Berengaut gets a few more days in the sun, which he surely earned by agreeing to be my first interviewee. And I have learned that lesson, so I am one step closer to podcast mastery. But while you're waiting for the new interview, do seek out and buy Karen's book. It deserves a place on the bookshelves of everyone who loves historical intrigue. It’s not only a great story but a beautiful book (on which, see my earlier post, “The Beauty of Books”)

As I finish this post, the horrific news about the school shooting in Connecticut has come over the air, which exposes my petty concerns and irritations for the trivia they are. My heart goes out to those affected, especially the children. Peace and love to all in this season of goodwill!

As if editing were not enough, my relaxation method of choice is classical ballet. I took class as a small child and went back to it only in my late twenties. As a result, I have no illusions that I will ever dance well. For a long time, I continued to get better, and that kept me going. But classical ballet is an unforgiving discipline: even the best dancers strive in vain to achieve perfection; and in time, the body rebels. The knowledge remains, but the ability to attain the goal slowly declines.

My other hobby, writing fiction, also came to me in midlife and required long years of beating my head against a wall trying to improve without fully understanding what improvement required. I've heard it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master any skill, and I have the experience to prove it: ten years of ballet to go from klutz to not-so-awful; ten years of fiction writing before I hit my stride. The editing is harder to measure, because I'm not sure exactly when I went from newbie to pro, but I've been comfortable with it for at least half of my almost two decades on the job.

So why I thought I could conquer the mysteries of audio capture software in a couple of interviews escapes me. Even so, when I finished an absolutely wonderful conversation with Karen Engelmann, author of The Stockholm Octavo—which I highly recommend (as do the New York Times Book Review and the Indie Book Awards, among others)—only to discover that for reasons that remain cloudy the software had captured my voice but not hers, I was livid. I don't mean quiet, ladylike annoyed. I mean pounding on the floor, take a drive in the car so I could scream without upsetting Sir Percy and the cats infuriated. Such a wonderful conversation! Such a great interview! And no one would ever hear it except me.

I'm sure that whatever the problem was, it came about through user error. Yes, it seems absurd to me, a regular person, that after I told the software program to call up Skype and record what it heard, its default position caused it to save only what came in through the microphone and not the person at the other end of the call. But if I had a better sense of what I was doing, I could have recognized the problem and fixed it before I wasted 45 minutes of Karen's time. Alas, that didn't happen.

The good news is that she's still talking to me. If I practice over the weekend, I should have a new interview up at New Books in Historical Fiction by the end of next week. Julian Berengaut gets a few more days in the sun, which he surely earned by agreeing to be my first interviewee. And I have learned that lesson, so I am one step closer to podcast mastery. But while you're waiting for the new interview, do seek out and buy Karen's book. It deserves a place on the bookshelves of everyone who loves historical intrigue. It’s not only a great story but a beautiful book (on which, see my earlier post, “The Beauty of Books”)

As I finish this post, the horrific news about the school shooting in Connecticut has come over the air, which exposes my petty concerns and irritations for the trivia they are. My heart goes out to those affected, especially the children. Peace and love to all in this season of goodwill!

Published on December 14, 2012 16:10

December 7, 2012

Potlatch and Publishing

When Does It Make Sense to Give Books Away?

As luck would have it, I am about one-quarter of the way through Kristin Gleeson’s Selkie Dreams as I sit down to type this post. It’s a novel about an Irishwoman, Máire McNair, who escapes her dreary Protestant father and his plans to marry her off to the man of his dreams by signing up as a missionary to the Tlingit in late nineteenth-century Alaska. A historical romance, which I like, and an unusual setting, which I also like. I’m hoping that Máire will settle down with one of the Tlingit, a young man educated by the missionaries who has reverted to his native culture. (Selkies, for those who don’t know, are Celtic seal spirits who can take human form but must always, eventually, return to the ocean and their own kind. Máire believes her mother to have been one.)

I mention the book here not only because it’s worth the read if you like historical romance but because one of the Tlingit customs that particularly upsets the missionaries is the potlatch, in which people vie to give away cherished possessions—a custom that strikes the missionaries, for whatever reason, as sublimely uncivilized.

Tlingit Dancers at a Potlatch, 1898

Tlingit Dancers at a Potlatch, 1898

Courtesy of the University of Washington Digital Collections

Now customs are customs, and I’m no Victorian capitalist missionary to judge the ways of the Tlingit. But I do find it odd that the world of indie publishing seems to be caught up in its own kind of potlatch, in which authors who have spent years of their lives crafting a work of fiction vie for the right to offer it to the public free of charge in the hope of boosting sales.

Now, if someone tells me s/he has such plans, I keep my mouth shut unless the writer asks for my opinion, and few do. But as a marketing strategy, the logic of this behavior has always escaped me. Yes, I understand about loss leaders and giving the razors away for next-to-nothing to drive sales of razor blades. I know that search algorithms use brute numbers in calculating which results to list first, and since a large part of selling a new book by a first-time author is letting the public know that the book exists (not to mention differentiating it from the zillion other books being produced at the same time), hitting the top of these lists has value. But it still seems to me that the strategy of giving a book away for a period of time pays off best for writers who have other—preferably several other—titles already written and available for purchase. In that case, when the person trawling for free downloads clicks on one book and likes it, the person may be persuaded to pay cash for other books by the same author—right then, right there. Otherwise, the thousand people who download a book for free will seldom pay to buy that book—why should they?—and by the time the next book rolls around, they will have gone on to other authors. The author of one book may gain in popularity and search results, but it's not clear that s/he actually sells more books.

For that reason, even though I now have two novels in print, I had pretty much decided not to make my books available for free until I had at least a couple more titles out the door. Instead, I've sought other ways to publicize my books, counting on word of mouth, the building of relationships through social networks, and my role as the host of New Books in Historical Fiction to produce a slow but, one hopes, steady improvement in sales. I also set the prices at a level I could sustain over time or, if the occasion seemed to warrant it, reduce without forfeiting all profit from my work.

Nevertheless, as you can see from the widget at the top right corner of my blog, I have decided to participate in a GoodReads giveaway. Between now and December 31, GoodReads members in the US, the UK, and Canada can sign up to win one of two signed copies of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel.

Is this a contradiction? I don’t think so. For one thing, I’m well aware of my own limitations when it comes to marketing. The argument I sketched out above could be completely wrong—ill suited to the new ways of doing business. I won’t know unless I test the waters, and a GoodReads giveaway is a pretty safe test. I myself am curious to see what happens.

What has happened so far is that the number of people listing The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel as “to-read” has quintupled in the last 72 hours. This clearly results from the giveaway, because the numbers for The Golden Lynx haven’t budged. Sales also haven’t budged, but that’s hardly surprising: people who have signed up to win something cannot be expected to buy the product before the giveaway ends.

But the big questions remain. Will the giveaway increase sales, or will the people who don’t win just sign up for the next giveaway by another author? If people do read The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel and like it, will they then buy The Golden Lynx? If neither of those things happen, will the giveaway raise my profile or increase traffic to my blog or assist my attempts at marketing in some other way?

Stay tuned for the answers!

As luck would have it, I am about one-quarter of the way through Kristin Gleeson’s Selkie Dreams as I sit down to type this post. It’s a novel about an Irishwoman, Máire McNair, who escapes her dreary Protestant father and his plans to marry her off to the man of his dreams by signing up as a missionary to the Tlingit in late nineteenth-century Alaska. A historical romance, which I like, and an unusual setting, which I also like. I’m hoping that Máire will settle down with one of the Tlingit, a young man educated by the missionaries who has reverted to his native culture. (Selkies, for those who don’t know, are Celtic seal spirits who can take human form but must always, eventually, return to the ocean and their own kind. Máire believes her mother to have been one.)

I mention the book here not only because it’s worth the read if you like historical romance but because one of the Tlingit customs that particularly upsets the missionaries is the potlatch, in which people vie to give away cherished possessions—a custom that strikes the missionaries, for whatever reason, as sublimely uncivilized.

Tlingit Dancers at a Potlatch, 1898

Tlingit Dancers at a Potlatch, 1898Courtesy of the University of Washington Digital Collections

Now customs are customs, and I’m no Victorian capitalist missionary to judge the ways of the Tlingit. But I do find it odd that the world of indie publishing seems to be caught up in its own kind of potlatch, in which authors who have spent years of their lives crafting a work of fiction vie for the right to offer it to the public free of charge in the hope of boosting sales.

Now, if someone tells me s/he has such plans, I keep my mouth shut unless the writer asks for my opinion, and few do. But as a marketing strategy, the logic of this behavior has always escaped me. Yes, I understand about loss leaders and giving the razors away for next-to-nothing to drive sales of razor blades. I know that search algorithms use brute numbers in calculating which results to list first, and since a large part of selling a new book by a first-time author is letting the public know that the book exists (not to mention differentiating it from the zillion other books being produced at the same time), hitting the top of these lists has value. But it still seems to me that the strategy of giving a book away for a period of time pays off best for writers who have other—preferably several other—titles already written and available for purchase. In that case, when the person trawling for free downloads clicks on one book and likes it, the person may be persuaded to pay cash for other books by the same author—right then, right there. Otherwise, the thousand people who download a book for free will seldom pay to buy that book—why should they?—and by the time the next book rolls around, they will have gone on to other authors. The author of one book may gain in popularity and search results, but it's not clear that s/he actually sells more books.

For that reason, even though I now have two novels in print, I had pretty much decided not to make my books available for free until I had at least a couple more titles out the door. Instead, I've sought other ways to publicize my books, counting on word of mouth, the building of relationships through social networks, and my role as the host of New Books in Historical Fiction to produce a slow but, one hopes, steady improvement in sales. I also set the prices at a level I could sustain over time or, if the occasion seemed to warrant it, reduce without forfeiting all profit from my work.

Nevertheless, as you can see from the widget at the top right corner of my blog, I have decided to participate in a GoodReads giveaway. Between now and December 31, GoodReads members in the US, the UK, and Canada can sign up to win one of two signed copies of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel.

Is this a contradiction? I don’t think so. For one thing, I’m well aware of my own limitations when it comes to marketing. The argument I sketched out above could be completely wrong—ill suited to the new ways of doing business. I won’t know unless I test the waters, and a GoodReads giveaway is a pretty safe test. I myself am curious to see what happens.

What has happened so far is that the number of people listing The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel as “to-read” has quintupled in the last 72 hours. This clearly results from the giveaway, because the numbers for The Golden Lynx haven’t budged. Sales also haven’t budged, but that’s hardly surprising: people who have signed up to win something cannot be expected to buy the product before the giveaway ends.

But the big questions remain. Will the giveaway increase sales, or will the people who don’t win just sign up for the next giveaway by another author? If people do read The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel and like it, will they then buy The Golden Lynx? If neither of those things happen, will the giveaway raise my profile or increase traffic to my blog or assist my attempts at marketing in some other way?

Stay tuned for the answers!

Published on December 07, 2012 15:38

November 30, 2012

The Beauty of Books

A printed book is a work of art.

Don’t get me wrong. I love my iPad. I read on it, write on it, edit on it. I surf the Web, check my e-mail, and do the New York Times crossword puzzle on it. I use it to check Facebook and GoodReads, monitor Twitter, and even watch movies, after discovering to my surprise that they don’t look half-bad on the tiny screen. I like the convenience of downloading novels on a whim and of having an entire bookshelf at my fingertips. I turn my own novels into e-books and go through them as a reader would, looking for inconsistencies and problems. But e-books are, at least at this point in time, utilitarian. Print books are beautiful.

For example, take the book I finished last nigh: Karen Engelmann’s The Stockholm Octavo—which I highly recommend, so stay tuned for information on my interview with the author for New Books in Historical Fiction.

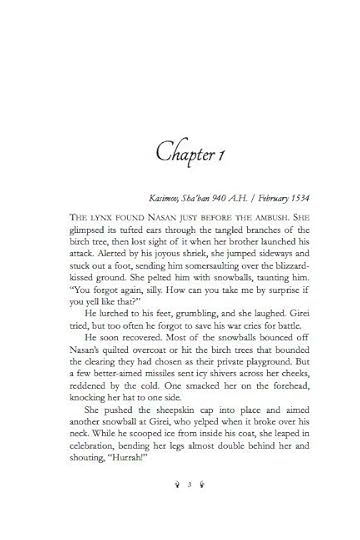

Even from the sample available at Amazon.com, you can see the work that went into this design. The font for the chapter numbers is an old-fashioned script, appropriate to the 18th-century setting of the book, and each opening page has the first few words reproduced behind the main text in light gray, as if someone had scratched them onto the page with a quill pen. The typefaces are clean and dark against soft cream paper, and the book has lots of white space to rest the eye. Some books include a colophon, giving information about the design and the typefaces used. This one, unfortunately, does not. The text looks as if it might be Adobe Garamond Pro or Minion Pro, but I can’t be certain. Whatever it is, it’s a nice, unfussy font to offset the elaborate script of the display type.

The design doesn’t stop there. The plot involves divination by cards, based on a 16th-century pack of German playing cards drawn by Jost Amman, and the book has sprinkled among the pages pictures of the cards, each neatly wrapped by the text. The script font appears again in the timeline that precedes the opening pages, contrasting the histories of Sweden and France in the years when the story takes place. The designer, Suet Yee Chong, has created an object as lovely and as complex as a multi-layered puzzle box. The effect is only highlighted by the thickness of the paper and the solidity of the cover (this book is cloth-bound).

For indie authors, this is the competition—and to be blunt, it sets a high bar. Ecco Books is an imprint of HarperCollins, one of the Big Six (publishers). These corporate firms command resources no indie author can match. Moreover, their work has shaped the expectations of readers, who judge self-published and small-press books by these standards.

So what’s an indie author to do? It’s bad enough that it takes years of your life to write and polish a novel, only to send it out to literary agents who give your query letter 90 seconds of their time before moving on. Now you have to become an editor, typesetter, cover designer, proofreader, and marketer, too?

Alas, the answer to that question is yes. You do. If you want to sell books, especially print books, you do. If you read the descriptions at various print-on-demand sites, you may think that you can get away with uploading your Word-compatible file. Which you can, but the results—unless you are an absolute Word whiz—will look, well, as if you typeset in Word. The physical book will be fine: CreateSpace, especially if you select the cream paper, produces a nice product. But unless you intervene in the formatting, the book will look unprofessional. The Big Six do not typeset in Word. They use Adobe InDesign or Quark XPress—expensive dedicated typesetting programs that do things Word users can only dream of. Even in an indie book, these programs make a difference.

I’ll use my own two novels as examples, because I know them best and own the rights to post screenshots of them. To start, let’s talk about some things that you can do in Word without a lot of effort. It’s relatively easy to set up a chapter title style that starts on a new page with spacing above and below and a specific typeface that you can change from book to book. If you compare the first pages in The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel (first) and The Golden Lynx (second), you can see that NESP uses Edwardian Script, a splashy 18th-century-like cursive with curlicues and rounded letters that evokes the time period of the novel: revolutionary France and aristocratic England in 1792. Lynx has chapter headings in Tangerine, an Arabic-style script with elongated letters that approximate in English the style that the heroine might have used in writing Tatar. Sites like FontSquirrel let you search for fonts, check their licenses, and download them free of charge. You can also buy fonts from dedicated fontmakers.

The body text in both books is set in Garamond, a classic serif typeface that has been around since the 16th century. It ships with Word. The first line of each opening paragraph, whether marking a new chapter or a new section within a chapter, is not indented, per standard publishing practice (note that The Stockholm Octavo does have indented first paragraphs for the chapters, although not for sections, presumably to show off the gray script). Again, most word processors let you set up a non-indented first line. The first line of each chapter also includes words in small caps: you can do this mechanically in Word but not as part of a style.

The font for the page numbers is the same in both books (Book Antiqua Italic, another old-fashioned serif font; I would have stuck with Garamond if I hadn’t been trying to establish a standard for Five Directions Press). The font used in the running heads matches that for the page numbers, which is also easy to do in Word.

Here, however, Word begins to falter. Chapter openers, again by convention, do not have running heads, since the chapter title orients the reader. Getting rid of them on pages where you don’t want them is a major pain, in contrast to InDesign, where I set up a master page for chapter openers and just drag it wherever I want to get rid of the running head.

Now let me show you two internal pages.

The type ornaments separating the sections (five-petaled flowers for NESP and Turkish daggers in Lynx) are centered with space above and below: if you have the right font, you can set those in Word. The page numbers, though, also have surrounding type ornaments that vary from book to book and reappear on the title pages. These are perfectly positioned in InDesign with something called a flush space, which expands as needed to fit the edges of an invisible box that contains the page number (calculated by the software) and the ornaments. As the page numbers go higher, the space between them and the ornaments contracts evenly on both sides while the dimensions of the invisible box remain unchanged. Word-processing programs have no equivalent. Controlling spacing, vertically justifying pages, managing paragraph breaks and page breaks: these things are more difficult, more time-consuming, and at times flat-out impossible in word-processing programs.

Not every feature is essential, of course. But as indie authors, it’s important to appreciate what book designers do, be realistic about how much work it takes to produce a beautiful book, and have a plan that involves more than typing THE END and uploading the file for a machine to process. At Five Directions Press, we edit our books in Word; design, typeset, and proofread them in InDesign; then create print-quality PDFs—just like the big boys. The only difference is that we print the final books through CreateSpace, because we don’t have the warehouses and distribution system of the Big Six.

That said, take heart! There are resources out there. For lots of specific and helpful advice, explore Joel Friedlander’s blog. Check back here, where I will continue to write about typesetting and publishing. And experiment. May each and every one of you produce a book as beautiful as The Stockholm Octavo.

Images © 2012 C. P. Lesley. All rights reserved.

Don’t get me wrong. I love my iPad. I read on it, write on it, edit on it. I surf the Web, check my e-mail, and do the New York Times crossword puzzle on it. I use it to check Facebook and GoodReads, monitor Twitter, and even watch movies, after discovering to my surprise that they don’t look half-bad on the tiny screen. I like the convenience of downloading novels on a whim and of having an entire bookshelf at my fingertips. I turn my own novels into e-books and go through them as a reader would, looking for inconsistencies and problems. But e-books are, at least at this point in time, utilitarian. Print books are beautiful.

For example, take the book I finished last nigh: Karen Engelmann’s The Stockholm Octavo—which I highly recommend, so stay tuned for information on my interview with the author for New Books in Historical Fiction.

Even from the sample available at Amazon.com, you can see the work that went into this design. The font for the chapter numbers is an old-fashioned script, appropriate to the 18th-century setting of the book, and each opening page has the first few words reproduced behind the main text in light gray, as if someone had scratched them onto the page with a quill pen. The typefaces are clean and dark against soft cream paper, and the book has lots of white space to rest the eye. Some books include a colophon, giving information about the design and the typefaces used. This one, unfortunately, does not. The text looks as if it might be Adobe Garamond Pro or Minion Pro, but I can’t be certain. Whatever it is, it’s a nice, unfussy font to offset the elaborate script of the display type.

The design doesn’t stop there. The plot involves divination by cards, based on a 16th-century pack of German playing cards drawn by Jost Amman, and the book has sprinkled among the pages pictures of the cards, each neatly wrapped by the text. The script font appears again in the timeline that precedes the opening pages, contrasting the histories of Sweden and France in the years when the story takes place. The designer, Suet Yee Chong, has created an object as lovely and as complex as a multi-layered puzzle box. The effect is only highlighted by the thickness of the paper and the solidity of the cover (this book is cloth-bound).

For indie authors, this is the competition—and to be blunt, it sets a high bar. Ecco Books is an imprint of HarperCollins, one of the Big Six (publishers). These corporate firms command resources no indie author can match. Moreover, their work has shaped the expectations of readers, who judge self-published and small-press books by these standards.

So what’s an indie author to do? It’s bad enough that it takes years of your life to write and polish a novel, only to send it out to literary agents who give your query letter 90 seconds of their time before moving on. Now you have to become an editor, typesetter, cover designer, proofreader, and marketer, too?

Alas, the answer to that question is yes. You do. If you want to sell books, especially print books, you do. If you read the descriptions at various print-on-demand sites, you may think that you can get away with uploading your Word-compatible file. Which you can, but the results—unless you are an absolute Word whiz—will look, well, as if you typeset in Word. The physical book will be fine: CreateSpace, especially if you select the cream paper, produces a nice product. But unless you intervene in the formatting, the book will look unprofessional. The Big Six do not typeset in Word. They use Adobe InDesign or Quark XPress—expensive dedicated typesetting programs that do things Word users can only dream of. Even in an indie book, these programs make a difference.

I’ll use my own two novels as examples, because I know them best and own the rights to post screenshots of them. To start, let’s talk about some things that you can do in Word without a lot of effort. It’s relatively easy to set up a chapter title style that starts on a new page with spacing above and below and a specific typeface that you can change from book to book. If you compare the first pages in The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel (first) and The Golden Lynx (second), you can see that NESP uses Edwardian Script, a splashy 18th-century-like cursive with curlicues and rounded letters that evokes the time period of the novel: revolutionary France and aristocratic England in 1792. Lynx has chapter headings in Tangerine, an Arabic-style script with elongated letters that approximate in English the style that the heroine might have used in writing Tatar. Sites like FontSquirrel let you search for fonts, check their licenses, and download them free of charge. You can also buy fonts from dedicated fontmakers.

The body text in both books is set in Garamond, a classic serif typeface that has been around since the 16th century. It ships with Word. The first line of each opening paragraph, whether marking a new chapter or a new section within a chapter, is not indented, per standard publishing practice (note that The Stockholm Octavo does have indented first paragraphs for the chapters, although not for sections, presumably to show off the gray script). Again, most word processors let you set up a non-indented first line. The first line of each chapter also includes words in small caps: you can do this mechanically in Word but not as part of a style.

The font for the page numbers is the same in both books (Book Antiqua Italic, another old-fashioned serif font; I would have stuck with Garamond if I hadn’t been trying to establish a standard for Five Directions Press). The font used in the running heads matches that for the page numbers, which is also easy to do in Word.

Here, however, Word begins to falter. Chapter openers, again by convention, do not have running heads, since the chapter title orients the reader. Getting rid of them on pages where you don’t want them is a major pain, in contrast to InDesign, where I set up a master page for chapter openers and just drag it wherever I want to get rid of the running head.

Now let me show you two internal pages.

The type ornaments separating the sections (five-petaled flowers for NESP and Turkish daggers in Lynx) are centered with space above and below: if you have the right font, you can set those in Word. The page numbers, though, also have surrounding type ornaments that vary from book to book and reappear on the title pages. These are perfectly positioned in InDesign with something called a flush space, which expands as needed to fit the edges of an invisible box that contains the page number (calculated by the software) and the ornaments. As the page numbers go higher, the space between them and the ornaments contracts evenly on both sides while the dimensions of the invisible box remain unchanged. Word-processing programs have no equivalent. Controlling spacing, vertically justifying pages, managing paragraph breaks and page breaks: these things are more difficult, more time-consuming, and at times flat-out impossible in word-processing programs.

Not every feature is essential, of course. But as indie authors, it’s important to appreciate what book designers do, be realistic about how much work it takes to produce a beautiful book, and have a plan that involves more than typing THE END and uploading the file for a machine to process. At Five Directions Press, we edit our books in Word; design, typeset, and proofread them in InDesign; then create print-quality PDFs—just like the big boys. The only difference is that we print the final books through CreateSpace, because we don’t have the warehouses and distribution system of the Big Six.

That said, take heart! There are resources out there. For lots of specific and helpful advice, explore Joel Friedlander’s blog. Check back here, where I will continue to write about typesetting and publishing. And experiment. May each and every one of you produce a book as beautiful as The Stockholm Octavo.

Images © 2012 C. P. Lesley. All rights reserved.

Published on November 30, 2012 17:35

November 21, 2012

New Books in Historical Fiction Now Live

Despite my ability to push Murphy’s Law to its limits, the New Books Network came through, and the first interview in NBN’s newest channel is now online and available for listening. Join me as I discuss The Estate of Wormwood and Honey with Julian Berengaut, an international debt negotiator turned novelist. You can also follow Julian on his blog—where he chats about Russian history at many different times and places.

The Estate of Wormwood and Honey reproduces the style of its setting, 1820s Ryazan (about 120 miles east of Moscow). This well-researched novel follows the journey of Nicolas Nijinsky, a young nobleman in search of justice from those who mistreated him in childhood and exiled him from his ancestral home. But as he puts his plan into action and wends his way through a Gogolian world rife with corruption, scheming, and family politics, Nicolas begins to wonder whether, after all, he has chosen the right path.

Enjoy! I should have another interview up around mid-December, but I can’t give you the name yet, because the author still has to agree. (Hope she doesn’t read that Murphy’s Law post!)

The Estate of Wormwood and Honey reproduces the style of its setting, 1820s Ryazan (about 120 miles east of Moscow). This well-researched novel follows the journey of Nicolas Nijinsky, a young nobleman in search of justice from those who mistreated him in childhood and exiled him from his ancestral home. But as he puts his plan into action and wends his way through a Gogolian world rife with corruption, scheming, and family politics, Nicolas begins to wonder whether, after all, he has chosen the right path.

Enjoy! I should have another interview up around mid-December, but I can’t give you the name yet, because the author still has to agree. (Hope she doesn’t read that Murphy’s Law post!)

Published on November 21, 2012 10:39

November 16, 2012

The Murphy's Law of Microphones

First came the purring. The good news: I'd asked the cat not to meow, and he refrained from meowing. Instead, he provided a nice, gentle purr, showing how happy he felt that he could sit in my lap despite the cold-hearted way I'd abandoned him last Friday to read from The Golden Lynx at my alma mater and my callous insistence on attending ballet class three times that week—right when he was getting comfy, too. Really, how could I complain just because the microphone turned the purr into a roaring jet engine, reverberating like a soundtrack while the hapless interviewee waited for me to dial him up via Skype?

Fortune, as they say, favored me. Right about the time I was wondering whether I would make things better or worse if I shut the cat in a room, he abandoned my lap and the purring for his favorite spot, my printer. Never mind that the poor printer now contains more fur than certain stuffed animals I've known, or that it makes pathetic mousey noises when I ask it to print. When the cat is lying on it, he can stay quiet and relaxed for hours. Which, when I'm facing a 45-minute conversation with someone I've never met for a podcast that I have no experience in creating but need to record for the general public and for posterity, seems like a great idea.

Better still, Sir Percy was ensconced in his office, in the midst of a conference call. Cat #2 much prefers to hang out with him during the day, so I had no need to worry about her either. (She had spent the morning reminding me of just how much noise she could make if she tried.) I had turned off the ringer on my phone, set my computer not to blank the screen, figured out how to keep the swivel chair from squeaking (don’t swivel), finished lunch, and left the coffee downstairs. No smacking, no slurping, no sniffling, no squeaking. No purring. I was ready.

I checked my microphone and recording equipment, as recommended in the NBN Hosts Manual. Well, I knew the microphone was working, since it had picked up the jungle purrs. But the Skype test call didn't record (I think I mentioned in a previous post that I am Skype-challenged). Then I realized the audio capture software works so much better if you click the Record button before recording. Sigh. I hadn't even made the call yet, and I was already down for two.

Let me emphasize that none of the glitches I'm relating here had anything to do with my interviewee, Julian Berengaut. He answered the phone right away and was the perfect gentleman as I staggered through my opening segment (three times, but who's counting). He even said nice things after the recording stopped. Not his fault that I mixed up the name of his publisher (re-record no. 1) or the channel I'm supposed to represent (re-record no. 2) before settling into something that at least didn't make me sound as if I'd dropped in from another planet and had trouble thinking in English. Nor was he responsible for Sir Percy drifting by about halfway through and forgetting the sixteen warnings I'd issued not to talk to me during the interview or Skype deciding to take a break five minutes before the end. Or for my microphone emitting the occasional howl for no obvious reason (why conceal its Braveheartyearnings for the first two-thirds of the conversation?).

There are only so many ways a person can mess up a podcast, and I think I found every last one. So I can't call myself a podcasting queen yet—maybe a podcasting plebe. Still, it was fun. And with luck, I didn’t foul things up to the point where Marshall Poe can’t compensate for my inexperience. As soon as I have the live link, I'll post it, on this blog and on Facebook. Then I'll start practicing, so I can do better next time. I’m determined to earn that crown sooner or later.

Meanwhile, you can follow Julian's blog at http://wormwood-and-honey.com. And check out his book. If you like Russian literature—especially Gogol—I'm sure you will love The Estate of Wormwood and Honey.

Published on November 16, 2012 17:17

November 11, 2012

Uncommon Women

I missed my usual Friday post this week because I was out of town, giving a reading from the early chapters of The Golden Lynx at my alma mater, Mount Holyoke College. I shared the stage (figuratively speaking—it was a lecture hall) with five amazing women: two poets, two writers of personal essays/memoirs, and one essayist who is working on a novel. It was a pleasure just to meet them—much more to hear them read.

We were there to celebrate the 175th anniversary of Mount Holyoke’s founding (the first women’s college in the United States) and because we have all published in The Lyon Review, the literary magazine for MHC alumnae, faculty, and staff. If you’re interested, you can find a description of the event, with links to the individual authors and their works, at http://thelyonreview.com. Soon the Lyon Review site will also include videotapes of the readings.

So let’s hear it for uncommon women,* who keep life interesting and ask awkward questions and refuse to stand by while others try to suppress their voices, their ideas, and their contributions.

Skinner Hall, Mount Holyoke College, ca. 1896It doesn’t look much different today.www.clipart.com

*The title comes from Uncommon Women and Others, a play by Wendy Wasserstein ’71 about her experiences at Mount Holyoke College.

We were there to celebrate the 175th anniversary of Mount Holyoke’s founding (the first women’s college in the United States) and because we have all published in The Lyon Review, the literary magazine for MHC alumnae, faculty, and staff. If you’re interested, you can find a description of the event, with links to the individual authors and their works, at http://thelyonreview.com. Soon the Lyon Review site will also include videotapes of the readings.

So let’s hear it for uncommon women,* who keep life interesting and ask awkward questions and refuse to stand by while others try to suppress their voices, their ideas, and their contributions.

Skinner Hall, Mount Holyoke College, ca. 1896It doesn’t look much different today.www.clipart.com

*The title comes from Uncommon Women and Others, a play by Wendy Wasserstein ’71 about her experiences at Mount Holyoke College.

Published on November 11, 2012 13:25

November 2, 2012

New Books in Historical Fiction

Or How I Became a Podcasting Queen

It seemed so simple in the beginning. Isn't that always the way? You take a step, and next thing you know, it leads somewhere you never anticipated. Not a bad place, necessarily, but one you hadn't imagined. So it happened to me.

As any reader of this blog knows, I have two relatively new novels to publicize. The not-so-hidden secret of the modern indie publishing world is that publishing is easy, but marketing is tough. So when I first learned about the New Books Network, I thought I had it made. The NBN site combines about seventy channels devoted to different types of new books (anything published within the last five years qualifies as new), ranging from art to world affairs and comics to critical theory. One of them covers historical fiction. Perfect.

But when I checked the page for the channel itself, it just said that NBN hoped to inaugurate the channel soon. Well, I thought (because I would be embarrassed to say this out loud), how better to inaugurate it than with my two books? So I contacted Marshall Poe, who created NBN and hosts the New Books in History channel, and suggested that he interview me. In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention that I have known Marshall for years; otherwise, I usually have trouble mustering that much chutzpah.

Only later did I find out that I had, in all innocence, violated the basic rule of academe: "first, do your research." I thought that NBN, because it was on the Web, stockpiled written interviews. A natural fit for a writer, right?

Not quite. Turns out that NBN interviews are podcasts, conducted over Skype. And what kept New Books in Historical Fiction from operating was that it had no host. Marshall solved that problem by offering me the job.

Oops. I don't listen much to podcasts, and I'd never imagined creating one. I don't even listen to audio books. As for Skype, it looks easy, but I had already tried it once and spectacularly failed to master it. Microphones, headphones, audio capture software: my head started spinning, and I hadn't even finished reading the instructions that promptly arrived by e-mail.

Moreover, even though these days I can conduct a conversation with strangers at parties, give lectures, and present the occasional reading of my own work, the super-shy high-school me still lurks in the shadows of my subconscious. Why else would I hide in my office and type novels for fun? I like learning new things, and I'm a geek at heart, so I especially enjoy mastering new technology. But Super-Shy Me was having fits. Could I make this work? Did I want to?

Well, to cut a long story short, Marshall talked me through the software and the equipment and the basics of interviewing writers. And I decided that becoming an NBN host was not only a great opportunity to market my own books but also a fantastic chance to meet other writers and learn something new. I've been practicing with the microphone and the headphones, selected a non-squeaky chair, and started requesting review copies and taking notes on new historical novels. I've even made some successful Skype calls and recorded myself practicing the talk I'm giving at the 175th anniversary celebration at Mount Holyoke College next week. I just have to figure out how to convince the cats not to meow at the wrong time; they're Siamese, and they always have plenty to say.

My NBN office setup, with the local celebrity,

ready for his interview, whether I like it or not © 2012 C. P. Lesley

Marshall is reading The Golden Lynx, and soon I will create my first podcast, in which he interviews me to introduce me as the new host. Then, when you go to http://newbooksinhistoricalfiction.com, you will see not the "we hope to launch very soon" message but an actual downloadable interview and a link to subscribe to future podcasts via iTunes. I'll be conducting interviews under my pen name, C. P. Lesley.

And if you write historical fiction and find a message from C. P. Lesley in your mailbox or on Goodreads, I hope you will consider giving me an hour of your time!

It seemed so simple in the beginning. Isn't that always the way? You take a step, and next thing you know, it leads somewhere you never anticipated. Not a bad place, necessarily, but one you hadn't imagined. So it happened to me.

As any reader of this blog knows, I have two relatively new novels to publicize. The not-so-hidden secret of the modern indie publishing world is that publishing is easy, but marketing is tough. So when I first learned about the New Books Network, I thought I had it made. The NBN site combines about seventy channels devoted to different types of new books (anything published within the last five years qualifies as new), ranging from art to world affairs and comics to critical theory. One of them covers historical fiction. Perfect.

But when I checked the page for the channel itself, it just said that NBN hoped to inaugurate the channel soon. Well, I thought (because I would be embarrassed to say this out loud), how better to inaugurate it than with my two books? So I contacted Marshall Poe, who created NBN and hosts the New Books in History channel, and suggested that he interview me. In the interests of full disclosure, I should mention that I have known Marshall for years; otherwise, I usually have trouble mustering that much chutzpah.

Only later did I find out that I had, in all innocence, violated the basic rule of academe: "first, do your research." I thought that NBN, because it was on the Web, stockpiled written interviews. A natural fit for a writer, right?

Not quite. Turns out that NBN interviews are podcasts, conducted over Skype. And what kept New Books in Historical Fiction from operating was that it had no host. Marshall solved that problem by offering me the job.

Oops. I don't listen much to podcasts, and I'd never imagined creating one. I don't even listen to audio books. As for Skype, it looks easy, but I had already tried it once and spectacularly failed to master it. Microphones, headphones, audio capture software: my head started spinning, and I hadn't even finished reading the instructions that promptly arrived by e-mail.

Moreover, even though these days I can conduct a conversation with strangers at parties, give lectures, and present the occasional reading of my own work, the super-shy high-school me still lurks in the shadows of my subconscious. Why else would I hide in my office and type novels for fun? I like learning new things, and I'm a geek at heart, so I especially enjoy mastering new technology. But Super-Shy Me was having fits. Could I make this work? Did I want to?

Well, to cut a long story short, Marshall talked me through the software and the equipment and the basics of interviewing writers. And I decided that becoming an NBN host was not only a great opportunity to market my own books but also a fantastic chance to meet other writers and learn something new. I've been practicing with the microphone and the headphones, selected a non-squeaky chair, and started requesting review copies and taking notes on new historical novels. I've even made some successful Skype calls and recorded myself practicing the talk I'm giving at the 175th anniversary celebration at Mount Holyoke College next week. I just have to figure out how to convince the cats not to meow at the wrong time; they're Siamese, and they always have plenty to say.

My NBN office setup, with the local celebrity,

ready for his interview, whether I like it or not © 2012 C. P. Lesley

Marshall is reading The Golden Lynx, and soon I will create my first podcast, in which he interviews me to introduce me as the new host. Then, when you go to http://newbooksinhistoricalfiction.com, you will see not the "we hope to launch very soon" message but an actual downloadable interview and a link to subscribe to future podcasts via iTunes. I'll be conducting interviews under my pen name, C. P. Lesley.

And if you write historical fiction and find a message from C. P. Lesley in your mailbox or on Goodreads, I hope you will consider giving me an hour of your time!

Published on November 02, 2012 14:41

October 26, 2012

Images, Images Everywhere

After a couple of posts on where to find free images for blogs and even, if you're lucky, for print, I decided to investigate some of the fee-based services on the Web. This is not a comprehensive list by any means, but even my small sample of three revealed some significant differences, so I thought my experience might help others, too. So here is my overview of what you can expect from Clipart.com; its affiliate Photos.com; and Shutterstock.

First off, why use a paid service at all when so much free stuff is available? My main reason is that I know for certain that if I paid to use the image (these are all royalty-free image sites), that I will not have copyright problems down the road. This assurance is particularly important for print, but copyright problems can undo the best intentions of bloggers and website owners as well. So for book covers, both my own and those we design for Five Directions Press, I prefer paying a small amount now to avoid possible trouble and large amounts later. I do check places like Wikimedia Commons and the WANA Commons Group on Flickr; and if I'm very sure of the terms, I will use what I find there, giving due credit to the photographer or noting the status as public domain. Same goes for the sites (libraries, museums, government agencies, etc., listed in my previous posts).

But if there is any ambiguity, I look for alternatives. For example, a gorgeous photo of a swan on a dark lake that I planned to make the basis of my cover for The Swan Princess appears on two different photo sites with two conflicting sets of copyright information: I stored them both for future reference, but to be safe, I will substitute a purchased photo when the time comes.

The three sites I'm discussing today differ in terms of price, availability of images, resolution, and requirements. As a result, each of them works well for different purposes.

Web (Blogs, Sites, Social Networks)

The least expensive is Clipart.com, which is great for blogs, websites, and posting to social networks. For about $12.50/month, if you sign up for a year at a time, you can download a ridiculously large number of images (up to 1,000/day), including photos, illustrations, vector images, clip art, and more. You don't have to sign up for a year, either. Subscriptions start at one month.

In addition to Photos.com, which I'll discuss in a minute, Clipart.com has an affiliated video site (Getty Images) and a link to Animation Factory, both available on the home page. I haven't used either, but they could be useful to bloggers and site designers.

Clipart.com also has fonts, although not many and not particularly interesting ones. It lets you search for multiple formats (GIF, EPS, JPG, PNG, Photoshop files, color vs. black and white, and more), categories, and creators. It has a lot of images and maps scanned in from old publications of various types, which is nice for historians and historical novelists. Almost all the images are low-resolution, which is fine for the Web, since computers don't care. And the selection is pretty good, although finding obscure things like "Tatars" can take a while.

Downloading's a snap. Click on the image, click on Download, and you're done. If there is copyright information, it appears on that download page. Often there isn't any. The site will produce a list of previous downloads on command, and the list includes all your Photos.com downloads. The link is on the home page whenever you're signed in.

Interior of Batu Khan's Tent www.clipart.com #77210

Web/Print

When you need a higher-resolution photograph, or even want to see what else is available that won't break your budget, try Photos.com. The Clipart site announces that images at its affiliate start at $1.99, but you have to buy a pretty big package for that. Ten images cost $34.99, which seems pretty reasonable, and you can choose high or low resolution. Twenty-five images cost $80.00, fifty images $134.99 ($2.70/image). One will set you back $7.99. Photos.com offers subscriptions, too, but they seem pricier than the Clipart version. Most images come in two sizes for the Web and one for print, but some are Web only.

I've found a couple of great shots on Photos.com: a fine alternative for the swan problem mentioned above; this great shot of a Kazakh tent, destined to adorn my cover for The Winged Horse (sequel to The Golden Lynx and about 1/5 of the way through its first draft); and another beautiful shot of Hampton Court for the back cover of Courtney J. Hall's soon-to-debut novel Saving Easton.

Tent on the Steppe, Kazakhstan

Hampton Court

The site has illustrations and clip art as well as photographs. The main drawback for me is that the photographs themselves are often not as dramatic as Shutterstock's, nor is the selection as wide-ranging. You have to search several times with different combinations of words to ensure you've identified all the options. For a cover image I'd check Shutterstock as a backup, just to be sure.

Again, downloading is simple. Click on the image you want, and a page opens with full copyright information (I print the page and save it to PDF for future reference, not least so that I can match the file numbers to the images). Choose the resolution you want and click Download. When you cite the image, you say © <Photographer>/Photos.com.

Print

Shutterstock has low-resolution images as well as high-resolution ones, but at $7–10 per image, who can afford to subscribe just to feed a blog or a website? Sure, you can get a subscription—if you happen to have a spare $249/month ($2,559/year). I don't, so I buy the 5-image/$49 pack and let it auto renew. I download the large size and reduce it as needed with Photoshop's phenomenal "Save for Web and Devices" feature. And while I have a few Shutterstock downloads floating around that I decided didn't work as well as I'd hoped, I try to avoid that problem by making extensive use of the site's wonderful light boxes (Photos.com has a light box, too, but everything goes in one place, whereas Shutterstock lets me set up different light boxes for different subjects).

Shutterstock has, without a doubt, the most beautiful and most varied photographs of any site I've tried, and it's blissfully easy to browse, search, and use. There's a free iPad app if you happen to be an iPad owner. It works great.

Shutterstock also has a quirk not found on the other two sites: you have to download all the images in your pack within a year and use any individual image within six months of downloading. Once you do, you confirm your right to use it thereafter. If you don't, you lose it. Why a site that charges per image objects to stockpiling downloads, I can't figure out. Maybe the problem has to do with the subscription plans, where you can download 25 images a day, and I misunderstood the small print. In any case, I am safeguarding my right to use some of these photos below, since the books they're intended to illustrate may not see the light for a while.

Horse on the Steppe

Pegasus

Mute Swan, Swimming

Shutterstock also has two kinds of licenses: Standard, which lets you reproduce an image 25,000 times; and Enhanced, which allows unlimited reproductions. Enhanced costs an additional $199. If I ever sell 25,000 books, I figure I'll have no trouble justifying the cost for the Enhanced license.

Downloading is easy—similar to Photos.com, as is obtaining a list of prior downloads. Copyright information is readily available, although the exact wording the service expects is not clearly laid out. I settled on © <Photographer>/Shutterstock, although earlier I used Shutterstock and the image number.

So that's my take on these three services. If you have experience with others, please leave a comment. I'd love to know about them!

All these photographs are copyrighted, so please do not borrow and use them without permission: Ger © Konstantin Kikvidze/Photos.com; Hampton Court © Anthony Baggett/Photos.com; Horse on the steppe © andreiuc88/Shutterstock; Pegasus © Nataliia Rashevska/Shutterstock; Swan © David Benton/Shutterstock. Many thanks to all the photographers and to the services that host them.

First off, why use a paid service at all when so much free stuff is available? My main reason is that I know for certain that if I paid to use the image (these are all royalty-free image sites), that I will not have copyright problems down the road. This assurance is particularly important for print, but copyright problems can undo the best intentions of bloggers and website owners as well. So for book covers, both my own and those we design for Five Directions Press, I prefer paying a small amount now to avoid possible trouble and large amounts later. I do check places like Wikimedia Commons and the WANA Commons Group on Flickr; and if I'm very sure of the terms, I will use what I find there, giving due credit to the photographer or noting the status as public domain. Same goes for the sites (libraries, museums, government agencies, etc., listed in my previous posts).

But if there is any ambiguity, I look for alternatives. For example, a gorgeous photo of a swan on a dark lake that I planned to make the basis of my cover for The Swan Princess appears on two different photo sites with two conflicting sets of copyright information: I stored them both for future reference, but to be safe, I will substitute a purchased photo when the time comes.

The three sites I'm discussing today differ in terms of price, availability of images, resolution, and requirements. As a result, each of them works well for different purposes.

Web (Blogs, Sites, Social Networks)

The least expensive is Clipart.com, which is great for blogs, websites, and posting to social networks. For about $12.50/month, if you sign up for a year at a time, you can download a ridiculously large number of images (up to 1,000/day), including photos, illustrations, vector images, clip art, and more. You don't have to sign up for a year, either. Subscriptions start at one month.

In addition to Photos.com, which I'll discuss in a minute, Clipart.com has an affiliated video site (Getty Images) and a link to Animation Factory, both available on the home page. I haven't used either, but they could be useful to bloggers and site designers.

Clipart.com also has fonts, although not many and not particularly interesting ones. It lets you search for multiple formats (GIF, EPS, JPG, PNG, Photoshop files, color vs. black and white, and more), categories, and creators. It has a lot of images and maps scanned in from old publications of various types, which is nice for historians and historical novelists. Almost all the images are low-resolution, which is fine for the Web, since computers don't care. And the selection is pretty good, although finding obscure things like "Tatars" can take a while.

Downloading's a snap. Click on the image, click on Download, and you're done. If there is copyright information, it appears on that download page. Often there isn't any. The site will produce a list of previous downloads on command, and the list includes all your Photos.com downloads. The link is on the home page whenever you're signed in.

Interior of Batu Khan's Tent www.clipart.com #77210

Web/Print

When you need a higher-resolution photograph, or even want to see what else is available that won't break your budget, try Photos.com. The Clipart site announces that images at its affiliate start at $1.99, but you have to buy a pretty big package for that. Ten images cost $34.99, which seems pretty reasonable, and you can choose high or low resolution. Twenty-five images cost $80.00, fifty images $134.99 ($2.70/image). One will set you back $7.99. Photos.com offers subscriptions, too, but they seem pricier than the Clipart version. Most images come in two sizes for the Web and one for print, but some are Web only.

I've found a couple of great shots on Photos.com: a fine alternative for the swan problem mentioned above; this great shot of a Kazakh tent, destined to adorn my cover for The Winged Horse (sequel to The Golden Lynx and about 1/5 of the way through its first draft); and another beautiful shot of Hampton Court for the back cover of Courtney J. Hall's soon-to-debut novel Saving Easton.

Tent on the Steppe, Kazakhstan

Hampton Court

The site has illustrations and clip art as well as photographs. The main drawback for me is that the photographs themselves are often not as dramatic as Shutterstock's, nor is the selection as wide-ranging. You have to search several times with different combinations of words to ensure you've identified all the options. For a cover image I'd check Shutterstock as a backup, just to be sure.

Again, downloading is simple. Click on the image you want, and a page opens with full copyright information (I print the page and save it to PDF for future reference, not least so that I can match the file numbers to the images). Choose the resolution you want and click Download. When you cite the image, you say © <Photographer>/Photos.com.

Shutterstock has low-resolution images as well as high-resolution ones, but at $7–10 per image, who can afford to subscribe just to feed a blog or a website? Sure, you can get a subscription—if you happen to have a spare $249/month ($2,559/year). I don't, so I buy the 5-image/$49 pack and let it auto renew. I download the large size and reduce it as needed with Photoshop's phenomenal "Save for Web and Devices" feature. And while I have a few Shutterstock downloads floating around that I decided didn't work as well as I'd hoped, I try to avoid that problem by making extensive use of the site's wonderful light boxes (Photos.com has a light box, too, but everything goes in one place, whereas Shutterstock lets me set up different light boxes for different subjects).

Shutterstock has, without a doubt, the most beautiful and most varied photographs of any site I've tried, and it's blissfully easy to browse, search, and use. There's a free iPad app if you happen to be an iPad owner. It works great.

Shutterstock also has a quirk not found on the other two sites: you have to download all the images in your pack within a year and use any individual image within six months of downloading. Once you do, you confirm your right to use it thereafter. If you don't, you lose it. Why a site that charges per image objects to stockpiling downloads, I can't figure out. Maybe the problem has to do with the subscription plans, where you can download 25 images a day, and I misunderstood the small print. In any case, I am safeguarding my right to use some of these photos below, since the books they're intended to illustrate may not see the light for a while.

Horse on the Steppe

Pegasus

Mute Swan, Swimming

Shutterstock also has two kinds of licenses: Standard, which lets you reproduce an image 25,000 times; and Enhanced, which allows unlimited reproductions. Enhanced costs an additional $199. If I ever sell 25,000 books, I figure I'll have no trouble justifying the cost for the Enhanced license.

Downloading is easy—similar to Photos.com, as is obtaining a list of prior downloads. Copyright information is readily available, although the exact wording the service expects is not clearly laid out. I settled on © <Photographer>/Shutterstock, although earlier I used Shutterstock and the image number.

So that's my take on these three services. If you have experience with others, please leave a comment. I'd love to know about them!

All these photographs are copyrighted, so please do not borrow and use them without permission: Ger © Konstantin Kikvidze/Photos.com; Hampton Court © Anthony Baggett/Photos.com; Horse on the steppe © andreiuc88/Shutterstock; Pegasus © Nataliia Rashevska/Shutterstock; Swan © David Benton/Shutterstock. Many thanks to all the photographers and to the services that host them.

Published on October 26, 2012 15:35

October 23, 2012

First Reviews of The Golden Lynx

Sorry for the delay, folks: I've been swamped with work and fell behind on my blog update this past week. So here is the latest—a short one—and Friday I'll try to get back on track with a comparison of the three paid image services I use: Clipart.com, its affiliate Photos.com, and Shutterstock.

The Golden Lynx has been selling pretty well for an indie book, but it hadn't picked up any reviews (well, not counting the one I wrote at Goodreads insistence—why does Goodreads ask you to rate your own books?!—and there I just pointed out that I was the author and therefore not a reliable reviewer) until last week, when Bryn Hammond posted this four-star review on Goodreads.

Note that Bryn (whom I don't know outside of Goodreads) is a specialist on the Mongols. You may want to check out her Of Battles Past, which is available for free on Smashwords or for 99¢ on the Kindle Store and draws heavily on The Secret History of the Mongols. I'm reading it now. So if Bryn says the book is accurate, you can be sure she knows what she's talking about.

And without more ado, here is what she said.

Bryn's ReviewI had fun. I’m going to make this a very, very personal review. It may or may not be of use to others.

First off: I came because I’m into steppe history. Mind, I know next to nothing about 16thC Russian-steppe outskirts... though I always thought Russia had the most interesting history on earth; I was happy to visit.

Next: I have a thing for fighting women. When they’re from the steppe I’m a guaranteed read. The more so, as to read certain steppe fiction, you’d think these were masculinist, macho societies where women were dragged by the hair. You’d think wrong: consult the steppe epics, that our girl Nasan knows and loves. When I found fighting women from The Book of Dede Korkut, for instance, cited here as aspiration-figures, the kind of girl Nasan wants to be, I was in.

Her people are now Muslim – in the way they are in Dede Korkut, that is, with strong underlines of their earlier religion. I’ve read about the conversion to Islam hereabouts in Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tukles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition (that's a mouthful. So, I'm afraid, is the book) - where I learn, conversion is slow and never perfect. So Nasan has her 'grandmothers', whom she feels to guide her, and a spirit doll (doll to Russian eyes) that she feeds daily, treats as holy, draws inspiration from.

But I don’t mean to get abstruse here, because this novel is an adventure. It kept reminding me of old adventure tales that I loved in my youth – Robert Louis Stevenson’s New Arabian Nights, for one, where people go about the night streets in disguises. It has a strong flavour of such fare – to me – and I can’t help but suspect the author is a fan of these old adventure tales too, since her other book is a take on the Scarlet Pimpernel. It’s very plotty. You know from the blurb, the infant Ivan the Terrible is involved ... and that plot blew a breeze of Alexandre Dumas at me, too.

There's what I liked about it: the setting (with sound historical knowledge); our girl hero whose heart is on the steppe though she’s plunked into Moscow to patch up a feud with a marriage; and the adventure, that conjured up to me the old-style books, you know, in the days when they knew how to write an adventure...

And here is another review, from a friend but unsolicited, sent in via e-mail:

I have the library copy of The Golden Lynx, I started reading it last night, and I’m immersed in the story. The story line is irresistible, and the details are fascinating. I feel like the kid I was when my mother hid my books so I could get my chores done.

The Golden Lynx has been selling pretty well for an indie book, but it hadn't picked up any reviews (well, not counting the one I wrote at Goodreads insistence—why does Goodreads ask you to rate your own books?!—and there I just pointed out that I was the author and therefore not a reliable reviewer) until last week, when Bryn Hammond posted this four-star review on Goodreads.

Note that Bryn (whom I don't know outside of Goodreads) is a specialist on the Mongols. You may want to check out her Of Battles Past, which is available for free on Smashwords or for 99¢ on the Kindle Store and draws heavily on The Secret History of the Mongols. I'm reading it now. So if Bryn says the book is accurate, you can be sure she knows what she's talking about.

And without more ado, here is what she said.

Bryn's ReviewI had fun. I’m going to make this a very, very personal review. It may or may not be of use to others.

First off: I came because I’m into steppe history. Mind, I know next to nothing about 16thC Russian-steppe outskirts... though I always thought Russia had the most interesting history on earth; I was happy to visit.

Next: I have a thing for fighting women. When they’re from the steppe I’m a guaranteed read. The more so, as to read certain steppe fiction, you’d think these were masculinist, macho societies where women were dragged by the hair. You’d think wrong: consult the steppe epics, that our girl Nasan knows and loves. When I found fighting women from The Book of Dede Korkut, for instance, cited here as aspiration-figures, the kind of girl Nasan wants to be, I was in.

Her people are now Muslim – in the way they are in Dede Korkut, that is, with strong underlines of their earlier religion. I’ve read about the conversion to Islam hereabouts in Islamization and Native Religion in the Golden Horde: Baba Tukles and Conversion to Islam in Historical and Epic Tradition (that's a mouthful. So, I'm afraid, is the book) - where I learn, conversion is slow and never perfect. So Nasan has her 'grandmothers', whom she feels to guide her, and a spirit doll (doll to Russian eyes) that she feeds daily, treats as holy, draws inspiration from.