C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 47

May 29, 2015

Hidden Assets

By now, it should be obvious that I am both a historian and a total book geek. I’m married to an academic, too, so the house groans with books. They lie three rows deep on the bookcases that line most rooms; they dot coffee and side tables, they lie in piles on the floor and form makeshift shelves under the desks. They lurk in iPad apps and online, waiting for their moment to shine. They are, without a doubt, the most valuable things we own: old books, Russian books, books that have survived a fire and leave smudges on the fingers of would-be readers. Most of the time, I know where mine are, but try finding a specific title when it means shifting a row of DVDs and plowing past sideways stacks and double verticals and books plucked from their usual locations because I started looking for something and had to stop before I was done. Move one, and only divine providence can shine a light on where it ends up.

By now, it should be obvious that I am both a historian and a total book geek. I’m married to an academic, too, so the house groans with books. They lie three rows deep on the bookcases that line most rooms; they dot coffee and side tables, they lie in piles on the floor and form makeshift shelves under the desks. They lurk in iPad apps and online, waiting for their moment to shine. They are, without a doubt, the most valuable things we own: old books, Russian books, books that have survived a fire and leave smudges on the fingers of would-be readers. Most of the time, I know where mine are, but try finding a specific title when it means shifting a row of DVDs and plowing past sideways stacks and double verticals and books plucked from their usual locations because I started looking for something and had to stop before I was done. Move one, and only divine providence can shine a light on where it ends up.The piles are particularly noticeable this week. I’ve been on writing vacation, and thanks to the efforts of my dedicated critique partners, The Swan Princess now has two solid first chapters, two more rapidly solidifying ones, and an amorphous mass that still needs to congeal into something readable. Part of this process involved researching superstitions and folk medicine among the Russians and Tatars—most notably, belief in the evil eye, widespread in Russia and Inner Asia as elsewhere around the world.

I began, as usual, on the Internet, where I pulled up some superb sources on Google Books—encyclopedias of women and childbirth, women and Islam, etc., the kind of tomes that sell for $300 a pop but will let you read a page or two for free. Then I remembered that somewhere in my study I had Nora Chadwick’s Oral Epics of Central Asia. Surely it would contain a mention of ghosts or goblins specific to the Tatar world.

It didn’t, in fact. More accurately, it had a lot, but the index did not list the particular demon mentioned in the encyclopedias. The book is still sitting on my desk waiting for a thorough go-through. But in the process, I discovered a ton of other material in books I had read years ago, information I hadn’t needed at the time I read it and so skipped over. These are the hidden assets of my post’s title. Among other things, I found:

an article detailing herbal cures for a wide variety of diseases, as practiced by Siberian peasants;

a second article in the same book about midwifery in the Russian village;

Will Ryan’s amazing The Bathhouse at Midnight: Magic in Russia (lots of information on the evil eye there, as well as the practice of “casting spells on the wind” against one’s enemies, from which comes the Russian word for “plague”);

George Lane’s Daily Life in the Mongol Empire, which discusses the overlap of Chinese, Islamic, and folk medicine among Nasan’s remote ancestors;

an article on childbirth customs in medieval Russia;

a translation of Alexander Afanasiev’s Russian Fairy Tales, which I had lost track of ever owning, because it was buried in row 3;

and Eve Levin’s Sex and Society in the World of the Orthodox Slavs, 900–1700, which I had definitely read and remembered but had forgotten contained quite so much fabulous information about attitudes toward everything from kissing to infanticide and the penalties for getting it wrong.

I could go on, but you get the point. There are many advantages—as well as a few disadvantages—of writing historical fiction from the perspective of a historian, but one of the best is the treasure trove of other people’s research decorating the bookshelves. Assuming, of course, that one can find the treasure map....

Image “Amulets against the Evil Eye” © 2006 FocalPoint, via Wikimedia Commons. Reused under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Published on May 29, 2015 07:21

May 22, 2015

Interwoven Threads

History is messy, with overlapping stories and mixed points of view. Although historians do their best to stick to the documented facts, most acknowledge that their efforts can take them only so far. Accepted truths change depending on point of view: rich or poor, male or female, York or Lancaster. The best we can do is try to distill a coherent account out of whatever varied opinions we find in the historical record, admitting that the results are necessarily incomplete. So many individual perspectives have not survived in archival documents, assuming they ever existed in documentary form. Indeed, the inability to establish a single, final version of “what actually happened” (with apologies to Leopold von Ranke) keeps historians in business: we can always revisit old debates or generate new ones based on previously unexplored evidence.

History is messy, with overlapping stories and mixed points of view. Although historians do their best to stick to the documented facts, most acknowledge that their efforts can take them only so far. Accepted truths change depending on point of view: rich or poor, male or female, York or Lancaster. The best we can do is try to distill a coherent account out of whatever varied opinions we find in the historical record, admitting that the results are necessarily incomplete. So many individual perspectives have not survived in archival documents, assuming they ever existed in documentary form. Indeed, the inability to establish a single, final version of “what actually happened” (with apologies to Leopold von Ranke) keeps historians in business: we can always revisit old debates or generate new ones based on previously unexplored evidence.Fiction, in contrast, tends to be neat. Sure, a given tale can follow large casts of characters through long, twisty plots. But good stories have structure, and structure demands a beginning, a middle, and an end. Everything has to hang together, or the reader loses interest. Plot consists not of random incidents but events carefully chosen to force the central character to change. Setting expresses the hero’s emotions at the moment in question; props and symbols foreshadow the eventual outcome. To paraphrase Anton Chekhov, a writer shouldn’t place a gun on the mantle at the beginning of the play unless she intends someone to fire it by the end. However winding the journey, the whole unwieldy vehicle of a novel staggers upward to an inevitable hilltop, then rolls down the far side to the resolution. That very neatness—the sense that here life makes sense, has a clear and identifiable purpose—constitutes much of the appeal of fiction for writer and reader.

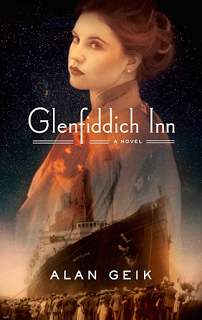

But sometimes an author wants to show a more multifaceted, messier view of a chosen location in a specific time while retaining the advantages of fiction. These advantages include the novelist’s freedom to imagine the inner worlds of people living in the past—although, of course, novelists also have a responsibility to ensure that their medieval knights don’t talk and think like twenty-first-century technocrats. One option is to feature a family—or related families. By juggling different story lines and multiple points of view, an author can create a more journalistic portrayal than one finds in a typical novel. This is the approach Alan Geik has taken in his debut novel Glenfiddich Inn: baseball and radio, war and propaganda, scheming in business and on the stock market, politics, medicine, and the suffrage movement all find a place in his exploration of Boston in the years during and immediately following World War I. We discuss these topics and more during our interview, held one hundred years, almost to the hour, after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania, an event with profound effects on his characters and the larger world they inhabit.

The rest of this text comes from New Books in Historical Fiction:

Boston in 1915 is a town on the move. Prohibition creates opportunities for corruption and evasion of the law. Stock scandals and political machinations keep the news wires humming. Women agitate for the vote, socialists for the good of the common man. A new sports phenomenon, the nineteen-year-old Babe Ruth, sparks enthusiasm for the local team by hitting one home run after another. A new invention called radio hovers on the brink of a technological breakthrough that threatens the established newspaper business.

Over it all hangs the shadow of what will soon be known as the Great War. Boston, like most US cities of the time, has large German and Irish populations that do not want to see their country fighting alongside Great Britain and France. Meanwhile, thousands of young men die daily in the trenches, and the RMS Lusitania sinks off the coast of Ireland, torpedoed by a German submarine captain who believes (perhaps rightly) that the British have stocked it with hidden munitions.

Through the overlapping stories of the Townsend and Morrison families in Glenfiddich Inn (Sonador Publishing, 2015), Alan Geik weaves these disparate threads into a compelling portrait of early twentieth-century Boston and New York.

Published on May 22, 2015 06:00

May 15, 2015

Vessels Large and Small

I haven’t written a history post in a while, mostly because I haven’t had time to research much, although I did spend months last summer and early fall trying to figure out exactly what a bright, literate, interested, but professionally untrained sixteenth-century teenager would know about medicine, especially if she came from the upper strata of society. More specifically, what would she know about heart disease? How would she imagine it? How would she cure it?

I haven’t written a history post in a while, mostly because I haven’t had time to research much, although I did spend months last summer and early fall trying to figure out exactly what a bright, literate, interested, but professionally untrained sixteenth-century teenager would know about medicine, especially if she came from the upper strata of society. More specifically, what would she know about heart disease? How would she imagine it? How would she cure it?Finding out the answers to these questions proved to be more difficult than I expected, but I did eventually learn enough about Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine (known throughout the medieval and early modern world) to get a sense of medical theory in 1530s Tataria. Hildegard von Bingen’s Physica was immensely helpful as evidence of herbal remedies in use in Europe at that time. Although the book itself was not well known then, it attests to a kind of on-the-ground practicality that Natalya Kolycheva, the senior female in my imaginary household, might have exhibited. I’m sure many more questions will arise as The Swan Princess progresses, but for the moment I’m in reasonable shape so far as medieval medicine is concerned. I can also look forward to the imminent publication of Toni Mount’s Dragon’s Blood and Willow Bark: The Mysteries of Medieval Medicine. With a title like that, the book’s got to contain a potion or two worth assigning to my heroine and those around her.

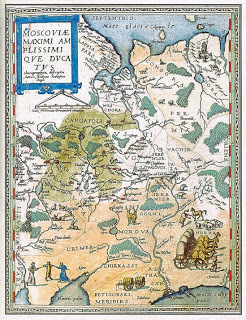

But if it’s not one thing, it’s another. Given that Natalya, bless her, is bent on traveling 400 miles despite being at death’s door, it seemed logical to me that she would go by water. I doubt it will surprise anyone to learn that in winter central and northern Russia is covered by snow and ice, and sledges drawn by sturdy horses have long provided swift and reliable transportation. But in spring and summer, the marshy ground turns to mud, then dries in unaccommodating ruts guaranteed to jolt a sick patient into agony, if not the next world, in no time flat. Since time immemorial, people have traveled along the rivers, which flow mostly north–south with tributaries flowing east–west and—in the case of the Dnieper, the Dvina, and the Volga—have their source in the Valdai Hills west of Moscow. The whole setup makes for an unparalleled transportation system that permits travel over thousands of miles with the occasional portage from one tributary to another.

So we are told in college. But just try to find out exactly what the boats looked like or how the rivers flowed in 1535. The Soviet state built a large reservoir in the middle of the Valdai Hills, so just determining what went where six centuries ago requires digging up old maps and balancing closeness to the time in question against the artistic license that mapmakers once permitted themselves. Anthony Jenkinson’s camels and bears and cormorants enliven his 1593 map no end, but it would be a mistake to take his delightful drawings as indicating the precision of a modern cartographer. And even when the maps seem good (I found an 18th-century specimen that looked pretty reliable), they may not include the exact tributaries I as a novelist need.

An article by the historian David Ransel—to whom I am now deeply indebted—alerted me to the detail that Dmitrov, a small principality about 45 miles northwest of Moscow that I had picked as my traveling party’s first stopping point, actually connects via a series of marshes and small rivers to the Volga, whence Natalya and her family can reach the White Lake with relative ease. A website listing all the routes that Vikings used to loot, pillage, and trade from Scandinavia to Constantinople and points east revealed several means by which my Russians could get from A to B seven hundred years later. Ransel again, in his book based on the diary of an 18th-century Dmitrov merchant, mentioned that the Valdai Hills were once the site of serious white water, endangering not only the inflexibly built merchant ships of the day but my novel’s plot. A heart patient shooting the rapids? Oops, back to the drawing board.

Then, as if that were not enough for one research adventure, I discovered that Russia in Muscovite times had almost no inns (a detail I had already suspected, but I had not realized the consequences). As a result, people either did not stop except to change horses (on land) or camped outdoors despite the swarms of gnats and black flies that rose from the marshes to torment everything that moved. Depending on the travelers’ social estate, they could stay with a fellow noble or in a handy peasant cottage or (especially if male) in a monastery. But foreign visitors often commented on the inadequate facilities for travelers and the consequent tendency to keep moving. Except for the rapids, which were a problem no matter what, floating along on a boat made reasonable sense. But the idea that a strict mother-in-law would casually wave her eighteen-year-old charge off to ride 400 miles with no supervision except that provided by a bunch of rough warriors defied belief. Back to the drawing board again.

In the end, none of these setbacks matter, of course. Research is fun; plot threads are always, to some extent, contrivances that can be overhauled; character triumphs, no matter what. But if there’s a moral to this story, it’s that no matter how long one studies a place and a time, there remains far more to be discovered. And despite the glorious riches of the Internet, finding the specifics in question can prove, at times, surprisingly difficult.

Published on May 15, 2015 13:26

May 8, 2015

Proof of Ownership

It won’t be news to those who regularly follow me here and on social media that both I personally and Five Directions Press, the writers’ cooperative that publishes my books, have been upgrading our websites over the last two months. We’re very happy with the results of the move, and on the whole the process has gone smoothly, but there have been little hiccups here and there. So given that this blog is in part about technology as experienced by those who are not especially tech-savvy (me), I thought I’d share my headaches with verification to reassure those still wandering in the wilderness, bereft of map, that the confusion really isn’t their fault.

It won’t be news to those who regularly follow me here and on social media that both I personally and Five Directions Press, the writers’ cooperative that publishes my books, have been upgrading our websites over the last two months. We’re very happy with the results of the move, and on the whole the process has gone smoothly, but there have been little hiccups here and there. So given that this blog is in part about technology as experienced by those who are not especially tech-savvy (me), I thought I’d share my headaches with verification to reassure those still wandering in the wilderness, bereft of map, that the confusion really isn’t their fault.Let me say straight off that I love Google. I have at least three accounts for different things; it’s a great search engine; it hosted my site for years and still manages the domain names—and all without charging a cent (except for the domain name registration, of course). Without it, I could never have gotten as far as I have. So any complaints have to be balanced against the reality that I don’t pay for the service, other than by supplying information (willingly or otherwise) to the ever-present Google bots.

That said, dealing with Google’s help files is a nightmare. It’s hard to name another collection of support files on the Web that so effectively combines reams of information with an almost total absence of answers to the simplest questions. I tried for years to verify my website, managed and hosted by Google, on my Google+ account. No matter how often I searched the help files and followed their instructions to the letter, Google refused to recognize the HTML code supplied by Google as valid. I moved the site to Wix, and the next time I checked Google+, the site appeared as verified even though I hadn’t done a thing.

Redirecting the domain name to the Wix servers was another odyssey—complicated by the detail that although GoDaddy acts as my registrar, I don’t actually have an account there, because it’s all managed through Google. The Wix support files walked me through that one—and again, for Five Directions Press. Wix also got me through adding the Google Analytics codes to my sites.

So, you can imagine my surprise (although, really, I should have expected it!) when I tried to verify the sites through Google’s Webmaster Tools and was told that I couldn’t use Google Analytics for that purpose because “the Google Analytics code appears to be malformed.” Malformed? Seriously? Not only had Google generated the code, but it was right there, gathering data in another browser window!

Whatever. I watched a help video, which repeated information I had just read in a bunch of help files, none of which told me how to get access to the header code on my website or to upload the HTML file or even to correct the “malformed” code. Instead, video and text just told me what should happen in an ideal world. I added myself as a verified owner—zilch. I added myself on Google Analytics—nope. I tried a different site, clearly linked to the Google Analytics account—that wouldn’t verify either; its code was “malformed,” too. I logged out of one account and into another, more closely associated with the site I was trying to verify—nada.

All this wasted an insane amount of time that I could have spent writing. Finally, I logged into the Wix site and began searching its help files. At first, nothing came up, but after clicking on a few links about HTML, I found the step-by-step instructions for adding a Google verification code to the header text on my site. Less than a minute later, I was done. Google found its tag and departed happy, throwing up a green check mark to indicate its joy. I repeated the process with the other site, and I was all set. And I didn’t even have to edit the darned HTML itself, as I had tried and failed to do in all the years I left the sites in Google’s tender care.

So this story has a happy ending. And the moral, I suppose, is that it’s true: you get what you pay for. Fair enough. Still, if a company is going to go to the trouble of creating an extensive help system, wouldn’t it be worthwhile to make it useful? The professional coders who write their own HTML aren’t, for the most part, the people struggling with the free templates on Google Sites. It’s not enough to tell us that we have to add a tag to the <header> area if we don’t know where to find the header area on our sites. Because if we knew, we might not be writers. We could support ourselves by coding—or producing competent help files....

On another note, The Winged Horse was featured a couple of weeks ago as part of Steve Wiegenstein’s series on the M. M. Bennetts Award long list. You can see the questions, answers, and overview on his blog.

Image no. 15328264 from Clipart.com.

Published on May 08, 2015 08:36

May 1, 2015

Turning Tables

Once in a while, I like to invite another author to guest post on my blog. This week, I pass the hat to Michael Schmicker, whose novel The Witch of Napoli came out earlier this spring to great acclaim. I loved it, and when you read this post, you will have a good idea why. Plus it’s always fun—especially with a historical novel—to see where an author got his or her ideas and how s/he transformed research into fiction. And with that, I retreat into the wings and leave the stage to Mike. If you’d like to find out more about him and his books, his contact information is at the end of the post.

Once in a while, I like to invite another author to guest post on my blog. This week, I pass the hat to Michael Schmicker, whose novel The Witch of Napoli came out earlier this spring to great acclaim. I loved it, and when you read this post, you will have a good idea why. Plus it’s always fun—especially with a historical novel—to see where an author got his or her ideas and how s/he transformed research into fiction. And with that, I retreat into the wings and leave the stage to Mike. If you’d like to find out more about him and his books, his contact information is at the end of the post.From Mike I had fun writing The Witch of Napoli.

The novel was inspired by the true-life story of Eusapia Palladino (1854–1918)—a middle-aged Neapolitan peasant woman who levitated tables and conjured up spirits of the dead in dimly lit séance rooms all across Europe at the end of the 19th century. Her psychokinetic powers baffled Nobel Prize-winning scientists and captivated aristocracy from Paris to Vienna. Her scandalous flirtations, her meteoric rise to fame, her humiliating fall and miraculous redemption, made world headlines at the time—when she died, she was famous enough to earn an obituary in the New York Times.

When you start with a life like hers, the story writes itself.

The fiery personality of my fictional heroine Alessandra closely mimics the real Palladino. Eusapia was hot-tempered, amorous, vulgar, confident—in a Victorian age where respectable women were insipid saints on a pedestal, stunted socially, sexually, intellectually, economically. She allowed strange men to sit with her in a darkened room holding her hands and knees and legs (“proper” women would have fainted or thrown themselves off a precipice if caught in that situation). She flirted and teased her male sitters, argued loudly, slapped an aristocrat who insulted her, flew at men who accused her of cheating (even when she did). Yet she was also extremely kind and generous to anyone in trouble, loved animals, gave to beggars. Her heart was large.

I did add a strong dash of Hollywood to the novel. Unlike the real Palladino, the fictional Alessandra is married to a sadistic gangster; she channels Savonarola, the famous 15th-century Dominican heretic burned at the stake; she falls in love with her upper-class mentor; she has a secret bastard; and the Catholic Church blackmails her. Pure fiction, all of it—but I like melodrama. Emotion and conflict create the beating heart of any gripping story.

Plotting was easy. I compressed 20 years of Palladino’s extraordinary life into a short 12 months but kept the factual arc of her controversial career intact. She’s discovered, tested, convinces Continental scientists her paranormal powers are real. England’s Society for Psychical Research (the novel’s fictitious London Society for the Investigation of Mediums) remains suspicious, invites her to England, catches her red-handed cheating. She returns home in disgrace. French and Italian scientists hang tough and demand one, final test. The winner-take-all showdown takes place in Naples. All true, by the way.

And those dramatic table levitations—surely they’re merely the product of the author’s imagination? Yes, some are. But others are slightly modified descriptions of spooky phenomena investigators actually witnessed at a sitting (she did hundreds, over two decades). Scientists today still heatedly debate whether Palladino was genuine or a complete fraud. She was caught cheating multiple times, yet she also produced, under extremely strict scientific controls, some of the most baffling and impressive feats of psychokinesis ever observed or photographed. Wikipedia owns the bully pulpit on Palladino but serves up a disappointing, simplistic dismissal of the best evidence for her genuineness, promoting instead a carefully curated collection of predominately skeptical experts and quotes. If there’s an afterlife, you can bet Palladino is fuming, fists raised.

My personal opinion? Palladino during her long career produced some genuine (though not necessarily supernatural) telekinetic effects. What do I base my opinion on? Primarily on parapsychological experiments confirming the reality of psychokinesis, which I describe in my nonfiction book Best Evidence; plus the exhaustive, 283-page Fielding Report published by England’s Society for Psychical Research, documenting the ten baffling sittings they conducted with Palladino in Napoli in 1908. Wikipedia whips up a whirlwind of speculation—from armchair critics who weren’t there—as to how Palladino might have cheated; I prefer the conclusion penned by the three veteran investigators who were actually there:

“With great intellectual reluctance, though without much personal doubt as to its justice ... we are of the opinion that we have witnessed in the presence of Eusapia Palladino the action of some kinetic force, the nature and origin of which we cannot attempt to specify, through which, without the introduction of either accomplices, apparatus, or mere manual dexterity, she is able to produce the movement of … objects at a distance from her and unconnected to her in any apparent physical manner.”

Somewhere, Eusapia is smiling.

You can find out more about Michael Schmicker at his website, friend him on Facebook, or follow him on GoodReads, Twitter, or Google+. The Witch of Napoli is available in print and for Kindle at Amazon.com.

Published on May 01, 2015 06:00

April 24, 2015

The Re-Created Past

However much historical novelists strive to portray the past in realistic ways, fiction can never be historically accurate in the scientific sense, for the simple reason that it requires an element of the imagination; otherwise, it is history, not fiction. Often a writer invents characters, but even if a novel focuses on the lives of real people, the author must fill in the gaps in the historical record. Depending on the distance between story time and the present, that may mean creating thoughts, feelings, conversations, or entire personalities. Details of daily life can also demand a considerable amount of research, followed by a necessary dose of invention. Good historical novelists try to keep the invention within the realm of the plausible, but that’s the best we can do.

However much historical novelists strive to portray the past in realistic ways, fiction can never be historically accurate in the scientific sense, for the simple reason that it requires an element of the imagination; otherwise, it is history, not fiction. Often a writer invents characters, but even if a novel focuses on the lives of real people, the author must fill in the gaps in the historical record. Depending on the distance between story time and the present, that may mean creating thoughts, feelings, conversations, or entire personalities. Details of daily life can also demand a considerable amount of research, followed by a necessary dose of invention. Good historical novelists try to keep the invention within the realm of the plausible, but that’s the best we can do.My latest interview with Erika Johansen, the author of a trilogy that begins with The Queen of the Tearling, goes beyond this typical approach to fictionalizing history. The world of the Tearling appears medieval, but it is wholly invented, describing a society that does not yet exist—and one that we may want to ensure never comes into being. The future society that Johansen portrays is not as dystopian as those in young adult favorites like The Hunger Games, but its reversion to the Middle Ages—one powerful, central church, nobles and vassals, short life spans and high infant mortality, limited education and literacy—neatly fits the definition of a place that one might enjoy in books or film but would not want to experience in real life.

Johansen holds up a mirror to our own obsession with technological prowess, our tolerance of a widening gap between rich and poor, our indifference to climate change and the environmental pollution that drives it. And she does so without preaching, through the story of nineteen-year-old Kelsea, destined by birth to become queen of the Tearling and prepared by her unconventional foster parents to defy the entrenched representatives of aristocracy and religion—if they don’t find a way to get rid of her first. The series raises disturbing questions: How far, really, have we come in the last five hundred years? How easily might we slip back, relinquishing our democratic ideals? How dependent are we on our technology? What safeguards have we constructed against a future we might prefer not to live?

Raising such questions without dictating answers, making them personal to each reader, is one of the great virtues of stories, no matter the time or setting in which they take place. So let us not forget, amid the necessary checking of facts, that emotions and sensations are at least as important to fiction.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Once in a while, we here at New Books in Historical Fiction like to branch out. This month’s interview is one example. Erika Johansen’s bestselling Queen of the Tearling blends past and present, history and fantasy, to create a future world that by abandoning its advanced technology (including, by accident, medicine) has reverted to a society that more resembles the fourteenth century than the twenty-fourth.

The world of the Tearling is not exactly the Middle Ages revived. The inhabitants know that life was once different, even though books have become scarce and computers nonexistent. They have learned the story of the Crossing, when a few thousand dreamers disgusted with the social stratification and environmental pollution around them decided to leave it all behind and start again on the other side of the Atlantic. And their idealistic young queen, Kelsea—raised in hiding to protect her from the savage politics of the center—yearns to restore her realm to the democratic and egalitarian principles of the founders. Assuming, of course, that she can survive on the throne long enough to establish her right to rule.

But treachery threatens Kelsea from within and without, by means military and magical. The greatest danger comes from Mortmesne, the kingdom to the east, where the Red Queen has ruled for more than a century. Kelsea’s first action as queen puts her on a headlong collision course with the Red Queen, with consequences that play out in book 2, The Invasion of the Tearling, due for release in June.

In The Queen of the Tearling (HarperCollins, 2014), Erika Johansen has created a thought-provoking and entertaining coming-of-age saga that both historical fiction and science fiction fans can enjoy.

Published on April 24, 2015 12:27

April 17, 2015

Laurel Leaves

Congratulations are due—no, not to me, although I’m still pretty chuffed about The Winged Horse having made it as far as the long list for the inaugural M.M. Bennetts Award for Historical Fiction. These congratulations are for those on the short list, whose names were announced this week: David Blixt (The Prince’s Doom), Greg Taylor (Lusitania R.E.X.), and especially Steve Wiegenstein (This Old World), who is generously reviewing and conducting a series of interviews with all the authors on the long list. You can find the interviews on his blog, starting now and continuing through at least the end of June. Questions about The Winged Horse just arrived, so check back soon for the link.

I have yet to read the three books that made the second cut, although I have begun Wiegenstein’s Slant of Light, which is remarkable for its ability to set a scene and draw the reader into the story world while providing just the right amount of local color and description. So I can readily believe that these three are the best of the best. I do know a number of the other authors on the long list, so I also accept that the committee had a tough decision to make in winnowing the field. I hope that M.M. Bennetts looks down and feels comforted by the warmth of her friends and their determination to honor her writing legacy.

And in case you’d like to expand your reading list, the long list of writers included, in addition to my book and the three listed above: Ella March Chase, The Queen’s Dwarf; PDR Lindsay, Tizzie; Elisabeth Marrion, Liverpool Connection; Mark Patton, Omphalos; David Penny, The Red Hill; Judith Starkston, Hand of Fire; Stephanie Thornton, The Tiger Queens; and Jeri Westerson, Cup of Blood. A wide range of times, places, and topics, so there should be something for everyone.

Of course, it would have been nice to see Winged Horse flying higher amid the clouds, but I am happy with the outcome. I don’t envy the committee as it struggles to cut the list from three names to one. I will sport my semifinalist emblem with pride, and I wish success to all the writers who entered—and especially to the chosen three as they advance to the next round.

I have yet to read the three books that made the second cut, although I have begun Wiegenstein’s Slant of Light, which is remarkable for its ability to set a scene and draw the reader into the story world while providing just the right amount of local color and description. So I can readily believe that these three are the best of the best. I do know a number of the other authors on the long list, so I also accept that the committee had a tough decision to make in winnowing the field. I hope that M.M. Bennetts looks down and feels comforted by the warmth of her friends and their determination to honor her writing legacy.

And in case you’d like to expand your reading list, the long list of writers included, in addition to my book and the three listed above: Ella March Chase, The Queen’s Dwarf; PDR Lindsay, Tizzie; Elisabeth Marrion, Liverpool Connection; Mark Patton, Omphalos; David Penny, The Red Hill; Judith Starkston, Hand of Fire; Stephanie Thornton, The Tiger Queens; and Jeri Westerson, Cup of Blood. A wide range of times, places, and topics, so there should be something for everyone.

Of course, it would have been nice to see Winged Horse flying higher amid the clouds, but I am happy with the outcome. I don’t envy the committee as it struggles to cut the list from three names to one. I will sport my semifinalist emblem with pride, and I wish success to all the writers who entered—and especially to the chosen three as they advance to the next round.

Published on April 17, 2015 06:00

April 10, 2015

More News

Last week I posted about developments at Five Directions Press, but our fellow-cooperative Triskele Books has news, too. For starters, just in time for Easter, it released a no-calorie treat, A Time and a Place: seven award-winning novels by seven different authors, packed into one gorgeous box. Seven journeys through time and place to:

Ancient Palmyra, fighting alongside a warrior queen (The Rise of Zenobia by Jane Dixon-Smith);Modern-day Anglesey, trailing a psychopath (Crimson Shore by Gillian Hamer);World War II France, to join la Résistance and fall in love with the enemy (Wolfsangel by Liza Perrat);Coventry, during the 1980s melting pot of racial tensions (Ghost Town by Catriona Troth);Charleville and the incredible adventures of a lost manuscript (Delirium: The Rimbaud Delusion by Barbara Scott-Emmett);Post-apocalyptic Wales, surviving with a rat pack (Rats by JW Hicks); andContemporary Zurich, where everyone has a secret (Behind Closed Doors by JJ Marsh).

As of April 3, 2015, the books are available to order from Amazon.com. (The link goes to the US store. If you want the UK store, click on the Triskele link at the top of the page.) A box of delights for less than the price of a large Easter egg. I’ve read a number of the individual books and enjoyed them all, so this is really a great deal.

But that’s not all. On April 17, 2015, Triskele is also organizing the 2015 Indie Author Fair at Foyles Bookshop, the big independent bookstore in the Charing Cross area of London. And in preparation, Triskele is hosting a Rafflecopter: forty different ebooks, paperbacks, or swag bag prizes. To sign up, go to the Triskele blog. But don’t wait, as you have less than a week to enter. And if you happen to be in London on April 17 (I wish I could be!), do stop by Foyles and see the Author Fair for yourself.

The last piece of news has to do with New Books in Historical Fiction, which posted two new interviews yesterday, neither of them by me. Our own is Libbie Hawker’s interview with George Stein about Sing before Breakfast: A Novel of Gettysburg, which went live almost to the minute of the 150th anniversary of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. But we also had our first cross-post, in which Siobhan Mukerji, the host of New Books in Law, interviews Sally Cabot Gunning about the legal issues associated with her Satucket Trilogy, a series of historical novels set in eighteenth-century America. Meanwhile, having polished off Laurie R. King’s delectable Dreaming Spies (no. 13 in her series featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes), the sequel to

Garment of Shadows

, I am gearing up for Erika Johansen’s Queen of the Tearling, to get her on the air (if all goes well) just in time for the release of her sequel, Invasion of the Tearling. Stay tuned!

The last piece of news has to do with New Books in Historical Fiction, which posted two new interviews yesterday, neither of them by me. Our own is Libbie Hawker’s interview with George Stein about Sing before Breakfast: A Novel of Gettysburg, which went live almost to the minute of the 150th anniversary of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. But we also had our first cross-post, in which Siobhan Mukerji, the host of New Books in Law, interviews Sally Cabot Gunning about the legal issues associated with her Satucket Trilogy, a series of historical novels set in eighteenth-century America. Meanwhile, having polished off Laurie R. King’s delectable Dreaming Spies (no. 13 in her series featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes), the sequel to

Garment of Shadows

, I am gearing up for Erika Johansen’s Queen of the Tearling, to get her on the air (if all goes well) just in time for the release of her sequel, Invasion of the Tearling. Stay tuned!

Ancient Palmyra, fighting alongside a warrior queen (The Rise of Zenobia by Jane Dixon-Smith);Modern-day Anglesey, trailing a psychopath (Crimson Shore by Gillian Hamer);World War II France, to join la Résistance and fall in love with the enemy (Wolfsangel by Liza Perrat);Coventry, during the 1980s melting pot of racial tensions (Ghost Town by Catriona Troth);Charleville and the incredible adventures of a lost manuscript (Delirium: The Rimbaud Delusion by Barbara Scott-Emmett);Post-apocalyptic Wales, surviving with a rat pack (Rats by JW Hicks); andContemporary Zurich, where everyone has a secret (Behind Closed Doors by JJ Marsh).

As of April 3, 2015, the books are available to order from Amazon.com. (The link goes to the US store. If you want the UK store, click on the Triskele link at the top of the page.) A box of delights for less than the price of a large Easter egg. I’ve read a number of the individual books and enjoyed them all, so this is really a great deal.

But that’s not all. On April 17, 2015, Triskele is also organizing the 2015 Indie Author Fair at Foyles Bookshop, the big independent bookstore in the Charing Cross area of London. And in preparation, Triskele is hosting a Rafflecopter: forty different ebooks, paperbacks, or swag bag prizes. To sign up, go to the Triskele blog. But don’t wait, as you have less than a week to enter. And if you happen to be in London on April 17 (I wish I could be!), do stop by Foyles and see the Author Fair for yourself.

The last piece of news has to do with New Books in Historical Fiction, which posted two new interviews yesterday, neither of them by me. Our own is Libbie Hawker’s interview with George Stein about Sing before Breakfast: A Novel of Gettysburg, which went live almost to the minute of the 150th anniversary of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. But we also had our first cross-post, in which Siobhan Mukerji, the host of New Books in Law, interviews Sally Cabot Gunning about the legal issues associated with her Satucket Trilogy, a series of historical novels set in eighteenth-century America. Meanwhile, having polished off Laurie R. King’s delectable Dreaming Spies (no. 13 in her series featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes), the sequel to

Garment of Shadows

, I am gearing up for Erika Johansen’s Queen of the Tearling, to get her on the air (if all goes well) just in time for the release of her sequel, Invasion of the Tearling. Stay tuned!

The last piece of news has to do with New Books in Historical Fiction, which posted two new interviews yesterday, neither of them by me. Our own is Libbie Hawker’s interview with George Stein about Sing before Breakfast: A Novel of Gettysburg, which went live almost to the minute of the 150th anniversary of General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. But we also had our first cross-post, in which Siobhan Mukerji, the host of New Books in Law, interviews Sally Cabot Gunning about the legal issues associated with her Satucket Trilogy, a series of historical novels set in eighteenth-century America. Meanwhile, having polished off Laurie R. King’s delectable Dreaming Spies (no. 13 in her series featuring Mary Russell and Sherlock Holmes), the sequel to

Garment of Shadows

, I am gearing up for Erika Johansen’s Queen of the Tearling, to get her on the air (if all goes well) just in time for the release of her sequel, Invasion of the Tearling. Stay tuned!

Published on April 10, 2015 06:00

April 3, 2015

Five Directions Press Expands

Five Directions Press is growing up—or at least growing. We released Courtney J. Hall’s much-awaited Some Rise by Sin this past week. You can find the links for the paperback and Kindle editions at the Five Directions Press site; a nook edition is underway and should be available within days. Here are the details for Some Rise by Sin:

Five Directions Press is growing up—or at least growing. We released Courtney J. Hall’s much-awaited Some Rise by Sin this past week. You can find the links for the paperback and Kindle editions at the Five Directions Press site; a nook edition is underway and should be available within days. Here are the details for Some Rise by Sin:Cade Badgley has just returned from an overseas diplomatic mission when he learns that his father is dying. Cade has no interest in filling his father’s shoes, but the inheritance laws of sixteenth-century England leave him no choice: he is the new Earl of Easton, with a hundred souls dependent on him, a rundown estate, and no money in his coffers. A friendly neighbor offers to help, but at a cost: Cade must escort the neighbor’s daughter Samara to London and help her find a husband.

Samara, a tempestuous artist, would rather sketch Mary Tudor’s courtiers than woo them. But her beauty, birth, and fortune soon make her the most sought-after young woman in London. As Cade watches her fall under the spell of a man he has every reason to distrust, he must balance his obligations to Easton against the demands of his heart and the echoes of a scandal that drove him away from his family twelve years before.

“Tudor history comes alive in this enthralling tale of a reluctant heir to an earldom and the high-spirited lady who wins his heart. An absorbing and memorable read.”

—Pamela Mingle, author of Kissing Shakespeare and

The Pursuit of Mary Bennet

“Some Rise by Sin is a sumptuous tale of romance, religious turmoil, and political intrigue set against the dramatic backdrop of the dying days of Mary Tudor’s reign. When the Earl of Brentford dispatches his unbridled daughter to the English court to find her own husband, will Samara choose wisely? Or will this naive country girl, who prefers sketching en plein air to playing the coquette, fall for the flattery of a deceitful seducer? With the keen eye of an artist, Courtney J. Hall paints a vivid picture, rich in historical detail, of this turbulent time of transition at the Tudor court.”

—Marie Macpherson, author of The First Blast of the Trumpet

In addition to a new book, we have a new author. Annabel Liu published eight collections of short fiction and literary essays in Chinese before sitting down to write her memoirs in English. Born in Shanghai, Annabel lived through the Japanese occupation during World War II, only to be whisked away to Taiwan when the Civil War ended in defeat for the Nationalist forces, for whom her father had been fighting for much of her childhood. After university, she moved to the United States, where she married, started a family, and and worked as a journalist for several US papers. She recounts these experiences in My Years as Chang Tsen: Two Wars, One Childhood and Under the Towering Tree: A Daughter’s Memoir. We are happy to welcome her.

In addition to a new book, we have a new author. Annabel Liu published eight collections of short fiction and literary essays in Chinese before sitting down to write her memoirs in English. Born in Shanghai, Annabel lived through the Japanese occupation during World War II, only to be whisked away to Taiwan when the Civil War ended in defeat for the Nationalist forces, for whom her father had been fighting for much of her childhood. After university, she moved to the United States, where she married, started a family, and and worked as a journalist for several US papers. She recounts these experiences in My Years as Chang Tsen: Two Wars, One Childhood and Under the Towering Tree: A Daughter’s Memoir. We are happy to welcome her.

Virginia Pye, the author of the exquisitely written River of Dust and the soon-to-be released Dreams of the Red Phoenix, comments: “In this beautifully written memoir, Annabel Lui tells the story of her family’s escape from China after the Civil War, settling first in Taiwan and then America. In vivid scenes, we see Liu’s traditional father inflict painful scars on her and other members of her family in his attempt to maintain dominance in a changing world. We cheer for her in this heroic and masterful tale as she succeeds in coming out from under his towering shadow.” Annabel is currently working on a third book in English, tentatively titled An Immigrant’s Memoir on Food.

In addition, we are included in Deb Vanasse’s article, “Joining Forces: The Why and How of Author Collectives,” which appeared in IBPA Independent in February 2015 and is now online. This article, which also quotes our friends at Triskele Books and Writer’s Choice, is well worth reading if you are considering setting up a cooperative of your own.

With all this change, we are putting a new emphasis on defining our brand and marketing. A Facebook ad for Courtney’s book reached 5,300 people, of whom almost 100 clicked through to find out more (bizarre as it seems, 2% is actually a great response for online ads). We have reorganized our book list on the website into five subcategories (past, present, future, remembered lives, young lives) to indicate the five directions, but we expect to do much more with the site in coming months. We have also been invited to participate in a local book fair celebrating independent authors, so expect to see announcements and updates for these things as spring turns into summer.

In passing, let me mention that Five Directions Press recently reissued our first book, The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel, in a smaller trim size. The text has not changed except to correct a few minor errors, so if you bought the book already there is no reason to buy it again. But if you are looking for the print book on Amazon.com, be aware that Amazon still favors the original printing. To find the new one, click on the Kindle edition, then click the little plus sign next to the word “paperback,” and you will see the new cover (shown above: you will know you are in the right place if you see the picture of Harvard’s Widener Library across the back cover and spine). Or just click this link or the one at the Five Directions Press site. Otherwise, it appears as if the book is out of print—which only the original version is.

We had considered reissuing The Golden Lynx and The Winged Horse in the smaller size as well, having discovered a way to keep the page counts almost the same. But after watching the computers in action, we decided to leave well enough alone. This is what happens when computers run the world....

Published on April 03, 2015 09:26

March 27, 2015

Chasing the Fog Machine

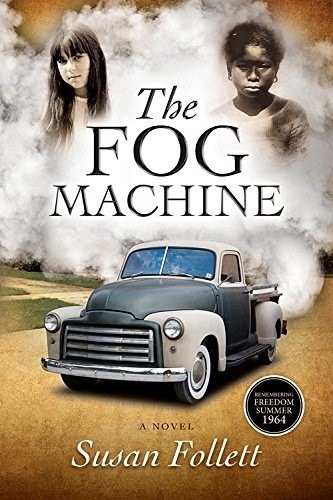

Until I opened Susan Follett’s novel, I had never heard of a fog machine. In the 1950s, apparently, they were widely used, particularly in the Deep South, to kill mosquitos. A specially fitted truck drove through town spewing clouds of insecticide, and the local children chased the trucks, weaving in and out of the clouds of sweet-smelling poison, heedless of the danger.

Until I opened Susan Follett’s novel, I had never heard of a fog machine. In the 1950s, apparently, they were widely used, particularly in the Deep South, to kill mosquitos. A specially fitted truck drove through town spewing clouds of insecticide, and the local children chased the trucks, weaving in and out of the clouds of sweet-smelling poison, heedless of the danger.As Susan Follett notes in her interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, this image of carelessly self-destructive innocents lured by something that only appears to be harmless is a perfect image for the deadly effects of prejudice—both for those discriminated against and, less obviously, for those who discriminate. This deeply thoughtful novel about what causes societies to accept and to resist change has a perhaps unanticipated resonance in the wake of the racial unrest that has afflicted the United States this past year. But it addresses the beginnings of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s, now half a century old but neither finished nor forgotten. Through the lives of its three main characters and their friends and families, the book explores the segregated South, the in some ways no less segregated North, and the efforts—most notably during the Freedom Summer of 1964—to guarantee liberty and justice for every citizen of the United States of America.

The rest of this post is from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Even without the almost daily headlines reporting racial injustice in Ferguson, New York City, Cleveland, Madison, and elsewhere, it would be difficult to grasp that fifty years have already passed since the March from Selma to Montgomery to protest discrimination against African-Americans. Events that take place in our own lifetimes or the lifetimes of someone we know do not seem like history, and recent Supreme Court decisions combined with the incidents that populate those headlines raise questions about the stability of the gains made during the Civil Rights Movement as well as the long path that the United States has yet to travel before it achieves its dream of equality for all.

In The Fog Machine (Lucky Sky Press, 2014), Susan Follett recreates the years before the March from Selma, before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Her book begins in the Deep South, still clinging to its Jim Crow laws, then moves to the Midwest in an exploration of prejudice both overt and covert and of the forces that promote change in individuals and in societies. The novel opens with Joan, a seven-year-old white girl in Mississippi desperate to fit in. Part of fitting in involves humiliating C. J., who cleans Joan’s family’s house and babysits once a week. When C. J. then leaves for Chicago, Joan is devastated. Surely her cruelty must be to blame.

But C. J. has her own reasons for leaving. Chicago welcomes her even as it confines her in a box labeled “live-in maid.” C. J. can’t imagine protesting this treatment; her parents have convinced her that safety means keeping her place. But as the 1950s give way to the 1960s, her friends from home question the wisdom of accepting the status quo. A man named Martin Luther King, Jr., is preaching civil disobedience. A boy named Zach is urging C. J. to help him change the world. And when Zach decides to take part in the Freedom Summer of 1964, C. J., too, wonders whether safety is the only thing that counts.

Published on March 27, 2015 06:00