C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 44

December 25, 2015

Goodbye, 2015!

Unbelievable as it sounds, at least to me, the last post for 2015 is upon us. It’s time to see how I did in meeting my goals for the year. Those were:

Unbelievable as it sounds, at least to me, the last post for 2015 is upon us. It’s time to see how I did in meeting my goals for the year. Those were:(1) free more time to write, without having unpaid bills;

(2) use that time to finish at least the rough draft of The Swan Princess;

(3) copy edit and typeset Some Rise by Sin for Five Directions Press;

(4) read twelve books and interview their authors for New Books in Historical Fiction;

(5) maintain this blog on a regular weekly schedule; and

(6) learn more about marketing, the weak link in most authors’ education, and certainly mine.

So, how did I do?

The first and most important goal, alas, remains elusive. To paraphrase a familiar saying about housework, bills seem to expand to consume the funds available, which remain less than last year’s despite a mad embrace of freelance editing projects on my part. Book sales are also down, despite modest success in a giveaway in June—in part because I published no new novels this year, and in part because the deluge of editing projects made it difficult to find time to promote the books that already exist. At least, that’s my guess.

Even so, I did manage to finish the rough draft of The Swan Princess, which I distributed to a half-dozen fellow writers for comments. I’ve implemented the small corrections already and am doing a bit of background research before I tackle the more comprehensive changes. I managed to find a fabulous book: 900 pages, give or take a few, detailing every surviving document covering the period between 1533 and 1547. I wanted it for Vermilion Bird, which I have already begun planning, but I’m discovering wonderful stuff for the earlier books, too. As I’ve mentioned previously, I don’t follow the history exactly, but I do try to stay out of its way. Once I work my way through the 1530s in this book, I expect to return to The Swan Princess with the goal of releasing it in the spring of 2015.

Goals 3, 4, and 5 went pretty well, too. Courtney’s book did appear in March; I did manage to post every week to this blog; and due to an anticipated flood of books near the end of the year, I exceeded my goal of twelve New Books in Historical Fiction interviews. I also learned something about marketing, through trial and error and thanks to Gloria Rabinowitz, the newest member of Five Directions Press. I worked on my blog until I found a design that I love. I moved my website and the press’s website to Wix.com, giving them a more professional appearance. I got better at social media, especially Facebook (Twitter still poses a bit of a challenge, mostly because of the time involved).

Five Directions Press, too, had a good year. Annabel Liu, another new member who agreed to list her memoirs with us, had two excerpts accepted for the WHYY NewsWorks blog EssayWorks; they went online just before Thanksgiving and last week. The press now has six authors and eleven books, with four more on the way, but we have been negotiating with individual writers in the hope of expanding our offerings. We have strengthened our ties with other coops and small presses, most notably Triskele Books in the UK, and have added a quarterly newsletter and two new pages to our site. The first, already visible although still in its infancy, is our More Books Worth Reading page. The second will begin in mid-January as a monthly feature on our Newsletter page, where we will recommend individual books that we recently read and loved. To receive the newsletter, sign up at our Contact page or via the entry page at http://www.fivedirectionspress.com.

Not too bad, altogether. Check back next week to see what I have in mind for next year. And in the meantime, have a wonderful holiday!

Image Clipart no. 109382127.

Published on December 25, 2015 06:00

December 18, 2015

A Crazy Week

The trouble with taking time off for the holidays (or anything, as most working people know) is the time before and after, which become so crazy busy that just finding time to breathe feels like it requires an appointment. And so it is for me.

As a result, I have little to share this week, except to wish you all a wonderful time with friends and family in whatever manner you choose to celebrate the winter solstice. I’ve spent the week dotting i’s and crossing t’s, not to mention re-editing a set of articles that were obsessively edited and proofed just last summer. But now they are going to a new publisher with its own styles, so I’m again frantic that I have missed this or ignored that or changed X but not Y. And I haven’t even started the three pieces that were never edited or the three being rewritten for the new publication.

That “fun” job awaits my return. Between this afternoon and the Monday after New Year’s Day, anyone who writes to my work address will receive a message that I have traveled to the sixteenth century—which is, indeed, where I intend to focus my time the next two weeks when not sharing it with my family or relaxing in the company of friends. I have research to do for The Vermilion Bird and revisions for The Swan Princess, and I intend to make the most of my gloriously uninterrupted hours, where the only travel I plan to undertake is in my head.

So let us all glory in the return of the light, in whatever form we celebrate it!

Next week is my annual round-up of goals set and goals met, so do check back then to see how I did in 2015.

And speaking of doing things, fellow Five Directions Press author Annabel Liu has another excerpt from her forthcoming memoir, When Chopsticks Meet the Hot Dog, on the WHYY Newsworks blog. Don’t miss it: she is a wonderful and often funny writer—perfect for the holidays.

Image Clipart.com #20490433

Published on December 18, 2015 09:25

December 11, 2015

Crowns and Roses

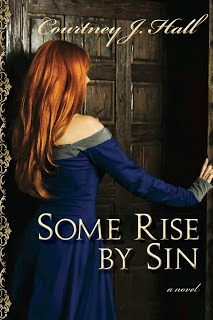

There’s a special joy in watching a book and an author come into their own. My latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction represents that kind of pleasure for me. I met Courtney J. Hall by accident: she responded to an ad that I didn’t even know had been placed, for writers to join a critique group that was just then forming. That was more than seven years ago, and we’ve been friends ever since. She is a wonderful writer, a talented graphic designer, and one of the three founding members of Five Directions Press, where she oversees cover design, various social media, and our quarterly newsletter.

There’s a special joy in watching a book and an author come into their own. My latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction represents that kind of pleasure for me. I met Courtney J. Hall by accident: she responded to an ad that I didn’t even know had been placed, for writers to join a critique group that was just then forming. That was more than seven years ago, and we’ve been friends ever since. She is a wonderful writer, a talented graphic designer, and one of the three founding members of Five Directions Press, where she oversees cover design, various social media, and our quarterly newsletter.Among other things, Courtney has a gift for producing back-cover blurbs: those pesky short descriptions that drive authors crazy. Write four hundred pages of novel? No problem. Distill those four hundred pages to a paragraph or two? The mere thought makes most of us sweat. So for all those reasons—and the simple fact that she’s a lovely human being—I was delighted to interview her about her debut novel, Some Rise by Sin . For those of you interested in the “alone together” concept that lies behind writers’ cooperatives, we also spend a few minutes discussing Five Directions Press.

Last but not least, I was impressed that she agreed, although I knew in advance that she would do a great job. Like many writers, Courtney feels more comfortable behind a computer screen than putting herself forward. It took courage to sit in front of a microphone, even with a friend, and talk about her early writing career and what led to the creation of Some Rise by Sin. (Although it would surprise anyone who encounters me these days, I too was once shy, so I sympathize.) So congratulations to Courtney, first for writing a lively and appealing novel focused on a lesser-known but vital transition in late Tudor England, then having the nerve to talk about it.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The reverberations of Henry VIII’s tumultuous reign continued to echo long after the monarch’s death. England teetered into Protestantism, then veered back into Catholicism before settling into an uneasy peace with the ascension of Elizabeth I. But for the survivors of the first two shifts, the approaching death of Mary Tudor in 1558 created great anxiety. No one knew, then, that Elizabeth would choose a path of compromise and (relative) tolerance. And Mary’s public burnings of Protestants gave much cause for concern that her sister might follow the same path with any Catholics who refused to recant.

Cade Badgley has served Mary well, even enduring imprisonment abroad for her sake. When he returns to England to discover his queen seriously ill and his own future changed by the death of his father and older brother, he has little choice but to manage the earldom dumped on his shoulders. But maintaining a crumbling estate without staff or money to hire them demands more resources than Cade can amass on his own. He turns to his nearest neighbor, who is happy to help—if Cade will return to the very court he has just abandoned, with the neighbor’s daughter in tow. Marrying off a lovely heiress will not strain Cade’s abilities much, but keeping her from pitchforking them both into trouble with her impetuosity and naïveté proves a far more difficult task. As the weeks pass, Queen Mary’s health worsens, and the future of England’s Catholics becomes ever more tenuous, the court is the last place that Cade wants to be.

In Some Rise by Sin (Five Directions Press, 2015), Courtney J. Hall neatly juggles politics, history, art, and romance during England’s brief Counter-Reformation, a moment when the Elizabethan Age had not yet begun.

Published on December 11, 2015 11:27

December 4, 2015

Rediscovering History's Losers

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I’m currently researching the background for the story that will become Vermilion Bird. The plan involves a plot that takes place between February and June 1537, an especially fraught three months in the unusually fraught period that was the minority reign of Ivan IV “the Terrible” (1533–47). Although I have no more intention than in any previous book of following the political events day by day, my own story as yet lacks any form that would make it worth discussing—and besides, I don’t want to give away spoilers for book 4 before book 3 even hits the shelves! So this post looks at the history on which I plan to tack my plot as needed.

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, I’m currently researching the background for the story that will become Vermilion Bird. The plan involves a plot that takes place between February and June 1537, an especially fraught three months in the unusually fraught period that was the minority reign of Ivan IV “the Terrible” (1533–47). Although I have no more intention than in any previous book of following the political events day by day, my own story as yet lacks any form that would make it worth discussing—and besides, I don’t want to give away spoilers for book 4 before book 3 even hits the shelves! So this post looks at the history on which I plan to tack my plot as needed.Only that history turns out to be far from easy to re-create. The reasons why have to do with the old saw that “history is written by the winners.” In this case, the “winner” (however temporarily) was Grand Princess Elena Glinskaya, the young mother of the future Ivan the Terrible. At the time, she was probably twenty-six or twenty-seven, and Ivan was six. Her power, always shaky because Muscovy didn’t like the idea of a woman in control, may have been starting to slip, although that too is speculation. We do know that her dead husband’s brother Yuri Ivanovich died in August 1536, reportedly of starvation, in the prison where the court nobles had confined him about ten days after Elena’s husband died. (That’s Yuri top right, looking remarkably healthy for a long-time prisoner about to expire, as portrayed in the Illustrated Chronicle Codex, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.) A few months later, Elena’s uncle, Prince Mikhail Glinsky, also died in prison. And in April 1537, rumors reached Moscow that “wicked people” had convinced Elena’s younger brother-in-law, Andrei Ivanovich, to flee his separate principality on the grounds that he was in disfavor with the royal court.

A trio of priests and two contingents of armed men were dispatched to stop him. Yet Andrei, unconvinced by his sister-in-law’s assurances that she bore him no ill will (because of the two contingents of soldiers? his attendance at Yuri’s funeral less than a year before?), ran off anyway. According to a chronicle set down about a hundred years after the events, he wrote to gentry military servitors in the merchant town of Novgorod, promising favors if they would join him. By the end of the month, Andrei was on his way to Moscow, traveling under a safe conduct that Grand Princess Elena would abrogate. He died in the same prison as his older brother Yuri before the end of the year.

How much of this story is true? How much did the chronicler invent? It’s hard to say. The tale is longer in later chronicles than in ones closer to the events being described, which is suspicious. But a chronicle can draw on older texts that are then destroyed—and in any case, the dating of old manuscripts is more an art than a science, at least at this point in time. So we can’t say absolutely that a detail is wrong because it appears in only one, relatively late source. But we can’t say that it’s right, either.

What has absolutely vanished is Andrei’s motivation. He is the loser in this conflict; his story remains only as the chronicler wished it to be told. Some details flatter the court in Moscow; others raise eyebrows. The grand princess and her supporters call him to service against Kazan, and he fakes illness to avoid presenting himself (again, urged by “wicked people” who wish to sow dissension between him and his loving family). They send clerics to reassure him of their good intent (but also those soldiers). They offer a safe conduct (then declare it null and void and punish the favorite who issued it). With his oldest brother dead of illness and his second brother murdered in captivity, Andrei had reason to worry. He had become the only surviving member of the older generation, the one around whom dissatisfied courtiers might rally. And he had learned from experience that Elena and her boyars would tolerate no such rallying point. But did he run in self-defense, or had he in fact decided (not without grounds) that both his own future and the country’s would look brighter if he, rather than his nephew Ivan, sat on the throne?

Andrei’s troubles were not the only events besetting Russia in 1537. The war with Lithuania finally dragged to a halt in the spring, when the two countries signed a five-year truce. The new khan of Kazan, feeling his oats and wanting (perhaps) to create a buffer zone between himself and his troublesome neighbor, launched a series of lightning raids on Muscovy’s eastern fortresses. Later that year, a new campaign against Kazan—retaliation for those raids—was called off only when the khan sued for peace. And within a year, Elena Glinskaya was dead, possibly poisoned, and the real chaos set in.

Plenty of material for fiction. And the novelist, unlike the scholar, can fill in the gaps and bring the losers back to life—so long as we remember that try as we might, we don’t really know. We’re just telling a story.

Andrei Staritsky in happier times, at his wedding in 1533. Again from the Illustrated Chronicle Codex via Wikimedia Commons. Both these images are in the public domain because of their age.

Published on December 04, 2015 06:00

November 27, 2015

Counting One's Blessings

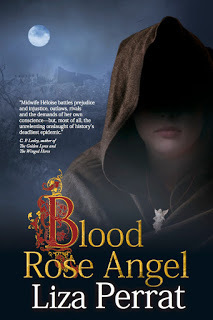

The Black Death is, I admit, an odd topic for a blog post scheduled for the day after Thanksgiving. It just so happens that my interview with Liza Perrat went live this week—which was not an accident, because we timed it to coincide with the November book launch for Triskele Books, her publisher, scheduled for tomorrow. If you are lucky enough to be in Central London, stop by and say hello. I’m not jealous—no, not one bit.

The Black Death is, I admit, an odd topic for a blog post scheduled for the day after Thanksgiving. It just so happens that my interview with Liza Perrat went live this week—which was not an accident, because we timed it to coincide with the November book launch for Triskele Books, her publisher, scheduled for tomorrow. If you are lucky enough to be in Central London, stop by and say hello. I’m not jealous—no, not one bit.Anyway, novels, as you probably know, explore the achievements and mistakes and decision making and responses of characters in trouble. It’s hard to imagine bigger trouble than being a healer in mid-fourteenth-century Europe, unaware that a plague of extraordinary virulence is about to land on your doorstep and wipe out most of the people you know. If you also happen to be a young woman with a family and a husband convinced that their survival should take precedence over some oath you swore to your long-dead mother, the stakes go up. If that long-dead mother left you a talisman that the local populace—desperate for a scapegoat as the number of plague victims mounts—believes could have demonic powers, they rise higher. And if your temperament does not fit contemporary ideals of submissive womanhood and your birth makes you suspect, finding a path through the morass of superstition and fear becomes, quite literally, a matter of life and death.

So in comparison we have, indeed, much for which to be thankful. Of course, epidemics, superstition, and war continue to plague us. Like a many-headed hydra, the world spawns new monsters each time the old ones suffer defeat. But for those of us who have friends and families, comfortable homes and good health, and careers—or at least hobbies—that we love, this is a day to give thanks. And to those who do not, let us try to extend a helping hand, even in the mad rush of shopping and preparations. Happy holidays!

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The year 1348 is not a good time to be a healer in Europe. Midwife Héloïse lives in a cottage outside Lucie-sur-Vionne, where she walks an awkward line between villagers who need her services and others who fear that she owes more to the black arts than to their medical counterparts. When she threatens an invading bandit chieftain with the power of her angel talisman, her enemies are more than ever convinced that she dabbles in witchcraft. But Héloïse has sworn an oath on her dead mother’s soul to help those in need, and she refuses to let a few hostile ignoramuses deter her.

Le mort bleu—known to history as the Black Death—arrives quietly on a ship from the east. At first, the villagers make little of it. But Héloïse’s husband, fresh in from Florence, recognizes the symptoms of the disease that has devastated Italy and orders his wife not to treat the sufferers, lest she bring pestilence into their house. The villagers’ suspicions mount with the body count, and Héloïse’s struggle with her husband intensifies as her concern for her family conflicts with her oath. When the local count takes an interest in Héloïse’s healing gift, even her talisman may not suffice to protect her.

Liza Perrat has written two previous novels in this series, Spirit of Lost Angels and Wolfsangel . Here, in Blood Rose Angel (Triskele Books, 2015) we learn the origins of the talisman and of the female healers who pass it from one generation to the next.

Published on November 27, 2015 06:00

November 20, 2015

Sleuthing among the Dusty Tomes

At heart, I will always be a historian first. Sure, I write novels—in part for fun and relaxation, in part to introduce a wider audience to this fascinating and little-known world that has preoccupied so much of my adult life. With help from my critique group and a small library of books, I have mastered the essentials of story structure, characterization, and the rest of the writing craft. I’m still learning, of course—who isn’t?—but I’ve reached the point where I can see trouble on the page, at least most of the time.

Yet I experience a special thrill when I start a new novel, because a new book means research. Research in printed archival sources; research in academic studies, some of them marvelously obscure; research in books written for children, whose authors don’t assume that the reader must know how sixteenth-century Russians constructed a fortress and don’t scruple to include full-color illustrations, each element marked. I look for photographs and films, run Internet searches in Russian, check government sites from Tatarstan to Tula and everywhere in between. And whatever I find goes into the Research folder in the Storyist folder assigned to that book. My memory, alas, isn’t what it used to be, so the contents of that folder sometimes take me by surprise. But so long as it’s written down, I’ll find it eventually.

Of course, research is not my only means of preparation. I change the desktop images on my computer and set up music playlists and photo collections for the new book, so that the sights and sounds of my imaginary world are constantly at my fingertips. I draw up goal, motivation, and conflict charts for all the major characters and jot down ideas for events that should take place. I write rough scenes, knowing they will not make it into the final book without massive revision—if they make it in at all. I write long notes to myself about what needs to go where. Having learned from Swan Princess, I probably won’t draw up a detailed outline for The Vermilion Bird. It’s a waste of time, when the outline invariably goes out the window within the first ten pages. Besides, I already know where this book needs to end up, and the history is dramatic enough to carry the rough outline of the plot. But I will work on the characters’ backstories and voices, their unique takes on each event as it occurs.

I love the whole process: the magic of watching the story unfold, the absorption in the lives of others (even if they are my own invention), the chance to bring a long-vanished world to life on the page. But most of all, I love the digging in my library, the revisiting with old acquaintances, the moments of realization that a much-needed detail lies right there, in a source previously ignored. By temperament, historians are detectives, ever pursuing nuggets of information through trails of documents that no one has examined in centuries. In this case, I am immersing myself in the politics of 1537, a year with enough going on to have left some traces in the record, but not so many that a novelist has nothing left to fill in.

So once again, as Sherlock Holmes would say, the game’s afoot. And the pathway to success lies through piles of dusty tomes. See you on the other side!

Quick note about my November 6 post: Some people read my statement that I was moving most of my books to Kindle Select as a decision to abandon print books altogether. Not so! I love print books and will produce my novels in print for as long as the technology remains available and affordable. The only change is that most of my novels are no longer listed as e-books on stores other than Amazon.com. That seems like the best decision under current circumstances, but technology changes constantly, so even that arrangement may not always stay the same. If you’d like to know more about my publishing plans, please send a message via my website. I’d love to hear from you.

Image: Clipart no. 23660559

Published on November 20, 2015 06:00

November 13, 2015

Art and Life

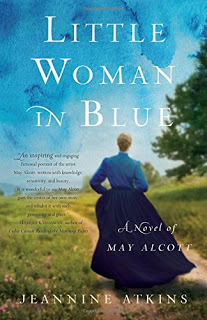

Last week I interviewed Jeannine Atkins for New Books in Historical Fiction. This was a special pleasure for me—not only because Jeannine proved to be a great conversationalist but because she writes about the Alcott women, as in Louisa May. As a girl, I loved Little Women, which until I began preparing for this interview I hadn’t realized typically included Good Wives (my editions were separate, as they sometimes are). I remember sobbing hysterically at Beth’s fate, which I will not spoil for you on the off chance that you have never read the books. Not to mention falling in love with Laurie, who in retrospect may have been my first romantic hero.

Last week I interviewed Jeannine Atkins for New Books in Historical Fiction. This was a special pleasure for me—not only because Jeannine proved to be a great conversationalist but because she writes about the Alcott women, as in Louisa May. As a girl, I loved Little Women, which until I began preparing for this interview I hadn’t realized typically included Good Wives (my editions were separate, as they sometimes are). I remember sobbing hysterically at Beth’s fate, which I will not spoil for you on the off chance that you have never read the books. Not to mention falling in love with Laurie, who in retrospect may have been my first romantic hero.That was a while ago, though, so before I indulged in Little Woman in Blue: A Novel of May Alcott , I thought I had better brush up a bit—not least because Atkins explicitly states that what drew her to her project was the gap between May, the youngest Alcott sister, and her fictional portrayal as Amy. May is on record as having said that she hated Little Women. Hate Little Women? How could she? I reread the series to find out.

At first, I had a hard time imagining what the fuss was about. Amy puts on airs and likes pretty things, but after all, she’s only twelve. And except when she burns her sister’s manuscript, she doesn’t do anything truly bad. But once I read May’s own story, I understood. Because in a way that was quite unusual for a young woman living in mid-nineteenth-century Concord, Massachusetts, May had a clear sense of who she was and what she wanted in life. Like Amy, she loved to paint, but unlike Amy, she refused to believe that a woman must either paint or marry, be an artist or a mother. May sought to combine love and career. She did not sacrifice her art; she did not spend her life alone—as her sister Louisa eventually did, despite intriguing hints of a romance with a Polish revolutionary.

As also happens today, May paid a price for her insistence on “having it all.” Family demands intervened, interfering with her art classes and slowing her mastery of her craft. Ambition took her away from home, and success brought her into conflict with her older sister Louisa, who resented May’s achievements even as she supported May financially. Balancing the competing interests was not easy, yet May persisted in creating the life she wanted, not the one society and her parents prescribed for her. That is a story worth telling, and Atkins tells it admirably. If you, too, were once an avid reader of Little Women, you definitely don’t want to miss this one. And if you weren’t, you may find reality more compelling than the dream.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Even people who have never read Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and its two sequels (Little Men and Jo’s Boys) probably have at least a vague memory of hearing about the March girls—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—whose father is away serving as a chaplain in the US Civil War and who often struggle to put bread on the table. Meg, the oldest sister, follows a conventional life for the time by marrying young and bearing twins. Jo, the rebel, forges a career as a writer. Beth is the homebody, sweet and uncomplaining. And Amy, the youngest sister, has artistic ambitions but surrenders them to marry the son of a wealthy man.

For all their realistic feel, the events in Little Women turn out mostly to be the product of its author’s imagination. This is nowhere more true than in Alcott’s portrayal of Amy, a fictionalized version of her youngest sister, May. In Little Women in Blue: A Novel of May Alcott (She Writes Press, 2015), Jeannine Atkins reintroduces us to the story of May’s life, focusing on her persistence against the odds, her refusal to accept the need to choose between career and family or settle for a genteel life in poverty, and her careful balancing of her own yearning to paint against the onslaught of domestic demands. From this richly detailed exploration of rivalry and sisterhood, we gain a new appreciation for an extraordinary woman, celebrated in her day but since obscured by her more famous sibling. May was, in the language of our own time, determined to “have it all.” Read this book to discover whether she succeeded.

Published on November 13, 2015 06:00

November 6, 2015

The Book Market in 2015

Last week, I took the first two novels in my Legends of the Five Directions series,

The Golden Lynx

and

The Winged Horse

, off the two non-Amazon sites where they have lived since they first went into print and enrolled them in Kindle Select. Four of my five novels—the exception is

The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel

, which Amazon for some reason considers ineligible (perhaps because the last time I tried this I forgot to allow a week for Barnes and Noble to “process” my change)—are now Kindle-only and will probably stay that way. The Swan Princess, when it appears in the spring of 2016, will be Kindle-only from the start.

Last week, I took the first two novels in my Legends of the Five Directions series,

The Golden Lynx

and

The Winged Horse

, off the two non-Amazon sites where they have lived since they first went into print and enrolled them in Kindle Select. Four of my five novels—the exception is

The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel

, which Amazon for some reason considers ineligible (perhaps because the last time I tried this I forgot to allow a week for Barnes and Noble to “process” my change)—are now Kindle-only and will probably stay that way. The Swan Princess, when it appears in the spring of 2016, will be Kindle-only from the start.This development troubles me, even though I am in a sense part of the problem. I stuck it out on the other sites for much longer than really made sense, but in the end the numbers defeated my commitment to keep my work available through multiple vendors. In the last ten months, I have sold exactly one e-book on Barnes and Noble. I sold two on the iTunes Store—both to an acquaintance who persisted long enough to purchase the books, despite repeated error messages and problems. I’m not exactly burning rubber on the Kindle Store either, but when I do sell e-books, that’s where I sell them. (Print books are independent of these calculations, but those have been Amazon-only from the start, except on the rare occasions when someone orders a book through a local bookstore.) So even though I am not sure how many subscribers the Kindle Unlimited service has—Amazon doesn’t release such figures—it seems logical to me to make as many books as possible available for borrowing as well as sales.

The other benefits of being in the Kindle Select program have not impressed me much, as I reported in previous posts. Lowering prices for a few days didn’t lead to many purchases. Making books free did lead to a lot of downloads but had no obvious long-term effects on sales or even book rankings. But the payments for borrowed books (although less) are competitive with sales, and if someone has chosen to pay $10/month for a subscription, it seems unreasonable to expect that person also to purchase books, given the number already available for borrowing.

Yet I do worry about what these results say about the state of the book business in general. Surely it can’t be good for one company to control the market so thoroughly—even if that company has made it possible for many authors, including me, to reach an audience. Already Amazon pays bonuses to the writers who sell the most, focuses its marketing on authors who contract with its publishing lines, and has killed the Breakout Novel Contest in favor of other, more restrictive avenues to securing those contracts. It uses its clout to drive out competitors, to pressure small publishing houses (and even big ones) to comply with demands for pricing and availability, and punishes those that resist. It has just opened its own brick-and-mortar bookstore to compete directly with the independent stores that have been making a comeback in the absence of the chains that it drove out of business.

This is not another “bash Amazon” post. The company is doing what companies do, and doing it well. It competes on pricing and service and reliability, and it deserves to succeed. For me as a writer, it has offered an opportunity I would not have enjoyed otherwise, and I am grateful for that. It’s been a great run, and I hope it continues for a long time. And if you have a Kindle and Amazon Prime or a subscription to Kindle Unlimited, please do click on the links above to read my books free of charge.

But I believe in free enterprise. I would like to see a little effective competition of a type that doesn’t simply exist but actively attracts both readers and writers. I think that would benefit all sides of the book business: readers, writers, and publishers. Even Amazon, which—if it becomes too big—will have to deal with the antitrust regulators and their insistence on breaking it up.

Takers, anyone?

On another note, The Swan Princess is now a complete, fleshed-out, reasonably coherent story, with three drafts under its figurative belt. It’s out to the first set of beta readers, and once everyone has a chance to submit her comments, one more thorough overhaul should see it ready to fly off to press. Meanwhile, I’ll be cooking up trouble for Legends 4, The Vermilion Bird (South). Cover peeks below, but remember, these images are copyrighted, both individually and in their component parts.

Tablet and books: Clipart no. 109120644.

Published on November 06, 2015 06:00

October 30, 2015

Dealing with the Dragon

And now, just in time for Halloween, I have a guest post to share about balancing legends, history, and imagination in historical fiction. Welcome to Joan Schweighardt, whose novel The Last Wife of Attila the Hun appeared this month. I will interview her for New Books in Historical Fiction early in the new year. Meanwhile, you can find her links and contact information at the end of the post.

Dealing With The Dragon…

and other challenges of combining legend and history in fiction

by Joan Schweighardt

Dealing With The Dragon…

and other challenges of combining legend and history in fiction

by Joan Schweighardt

Whenever I consider a legend about ancient times, I have to wonder if there is any truth to it. No one believed that Homer’s Iliad referred to any real historical events until an archeologist by the name of Heinrich Schliemann excavated a site he believed to have been the location of the so-called “fictional” Troy, in what is now Turkey. Not only were scholars forced to concede that Schliemann had in fact discovered the real Troy, but various objects found at the site seemed to confirm that many elements of Homer’s story were based on true events.

When I saw that some of the Germanic myths and legends that found their way into an Icelandic collection called the Poetic Edda made ambiguous but earnest attempts to bring the historical Attila the Hun into their narratives, I began to believe that there might be some tie-in between the legends and history. And when I began to research and found places where the historical and legendary materials seemed to intersect, I was inspired to start writing a novel based on my findings, the result of which is The Last Wife of Attila the Hun. Like Heinrich Schliemann, the more I excavated, the more I began to believe the legends were true—or at least based on some true events. I know there are many wonderful writers out there who don’t need that spark of truth in their legends or myths in order to mix them confidently with history, but I am not one of them.

Salmon Rushdie is. He has made his reputation in part on his talent for combining mythical/legendary and historical materials that are seemingly unrelated. Yet journalists never seem to tire of treating this propensity like something potentially risky. A month or so ago, when his new novel Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights came out, I noticed that several interviewers asked him the same question, which was, basically: Isn’t it counterintuitive to ask history and myth/legend to lie down together in the same bed?

The question made me think of my son, when he was a little boy. He used to love to play with GI Joe action figures back then. He had a huge collection of the vintage soldiers, each of which stood less than four inches high. When the twelve-inch figures came on the market, I thought he would like them too, so I bought him one. He was rather appalled. He tried to explain to me that the twelve-inch guys and the four-inch guys were like people from different planets. They were inharmonious, out of synch; they could not co-exist—let alone play together—in the same world.

The legends I drew from for The Last Wife of Attila the Hun, the Germanic legends that had found their way to Iceland, existed there as part of an oral tradition for centuries before someone bothered to record them. By that time the Germanic legends and myths had become so mixed up with Icelandic myths that it would be no more possible to pull out the pure strands of Germanic legend than it is to separate flakes of snow once they’ve fallen and settled together—if I’d only had the Poetic Edda to refer to. Luckily, the Germanic legends that traveled to Iceland had also remained in Germanic regions of Europe, and were recorded there too, again centuries after the period in time they describe. Most famous is an anonymously written epic poem called the Nibelungenlied. The fact that the legends in both the Poetic Edda and the Nibelungenlied attempt to pull historical figures (Attila as well as others) into their narratives gave me the courage I needed to mix history and legend (and yes, some myth too) together into one big pot.

My protagonist Gudrun (or Guðrún or Kriemhild) comes from the legendary materials, and of course Attila hails from the historical. The main point of intersect between the legendary and the historical materials is that the legends lead us to believe that Gudrun marries and kills Attila, while Roman historians writing at the time of Attila say that Attila did in fact marry a Germanic woman just before his death, and she may have killed him. That is the only obvious tie between them, but that was good enough for me. I was ready to start building bridges back and forth between the legendary and historical materials on my own after that. By the time I was done, I felt rather like Schliemann must have when his shovel first struck Troy.

My other challenge in combining legendary and historical materials was dealing with the dragon. According to the legends, Sigurd, Gudrun’s true love, goes up into the mountains with a dwarf named Regan who walked the earth when the gods did, to slay a dragon who is actually Regan’s brother (post shape shift), to avenge the death of Regan’s father (whom the dragon brother killed) and retrieve the gold that the dwarf-dragon stole. Among the pieces in the hoard is a cursed sword. Because of these and other magical elements, The Last Wife of Attila the Hun could have been a fantasy easily enough. But I felt that the inclusion of such starkly fantastic elements side by side with starkly historical ones would be too great a contrast and make the whole hodgepodge less compelling. So I opted to render the dragon stuff realistic by having it happen “off stage.” The reader never “sees” the dragon. He or she, however, knows exactly what the dragon looks like because he or she is there when Sigurd comes down from the mountain after slaying the creature and tells Gudrun’s brothers all the wonderful details about his adventure. Nor does the reader ever get the skinny on the gods or the Valkyries or the long-living dwarves from me, the author. He or she gets these details direct from the characters, from their conversations.

A friend of mine who was married to a great artist once said of her husband, “For him, every object, whether it is a person or an animal or a lamppost, is either something he might want to include in a painting one day or something he can dismiss.” At the very best of times, that is what writing feels like to me. In the case of writing of The Last Wife of Attila the Hun, my “I must have that” moment began when I first read the legends in the Poetic Edda. I am not the first person to be mesmerized and inspired by these legends. Wagner, who would have read not the Poetic Edda but the Nibelungenlied, based his Ring Cycle on them. Tolkien borrowed heavily from them as well. And so have many other writers (and painters). The interesting thing to me is that no two “offshoots” look alike. Every version I am familiar with is different than every other one. It may be risky to mix legend/myth with historical events, but I’m glad I did so, because having the chance to immerse myself in these materials was literary bliss.

Joan Schweighardt

Writer/editor

GreyCore Literary Services

www.greycoreliteraryservices.com

facebook.com/GreyCore

www.joanschweighardt.com

https://www.facebook.com/joanschweighardtwriter

twitter@joanschwei

Dealing With The Dragon…

and other challenges of combining legend and history in fiction

by Joan Schweighardt

Dealing With The Dragon…

and other challenges of combining legend and history in fiction

by Joan SchweighardtWhenever I consider a legend about ancient times, I have to wonder if there is any truth to it. No one believed that Homer’s Iliad referred to any real historical events until an archeologist by the name of Heinrich Schliemann excavated a site he believed to have been the location of the so-called “fictional” Troy, in what is now Turkey. Not only were scholars forced to concede that Schliemann had in fact discovered the real Troy, but various objects found at the site seemed to confirm that many elements of Homer’s story were based on true events.

When I saw that some of the Germanic myths and legends that found their way into an Icelandic collection called the Poetic Edda made ambiguous but earnest attempts to bring the historical Attila the Hun into their narratives, I began to believe that there might be some tie-in between the legends and history. And when I began to research and found places where the historical and legendary materials seemed to intersect, I was inspired to start writing a novel based on my findings, the result of which is The Last Wife of Attila the Hun. Like Heinrich Schliemann, the more I excavated, the more I began to believe the legends were true—or at least based on some true events. I know there are many wonderful writers out there who don’t need that spark of truth in their legends or myths in order to mix them confidently with history, but I am not one of them.

Salmon Rushdie is. He has made his reputation in part on his talent for combining mythical/legendary and historical materials that are seemingly unrelated. Yet journalists never seem to tire of treating this propensity like something potentially risky. A month or so ago, when his new novel Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights came out, I noticed that several interviewers asked him the same question, which was, basically: Isn’t it counterintuitive to ask history and myth/legend to lie down together in the same bed?

The question made me think of my son, when he was a little boy. He used to love to play with GI Joe action figures back then. He had a huge collection of the vintage soldiers, each of which stood less than four inches high. When the twelve-inch figures came on the market, I thought he would like them too, so I bought him one. He was rather appalled. He tried to explain to me that the twelve-inch guys and the four-inch guys were like people from different planets. They were inharmonious, out of synch; they could not co-exist—let alone play together—in the same world.

The legends I drew from for The Last Wife of Attila the Hun, the Germanic legends that had found their way to Iceland, existed there as part of an oral tradition for centuries before someone bothered to record them. By that time the Germanic legends and myths had become so mixed up with Icelandic myths that it would be no more possible to pull out the pure strands of Germanic legend than it is to separate flakes of snow once they’ve fallen and settled together—if I’d only had the Poetic Edda to refer to. Luckily, the Germanic legends that traveled to Iceland had also remained in Germanic regions of Europe, and were recorded there too, again centuries after the period in time they describe. Most famous is an anonymously written epic poem called the Nibelungenlied. The fact that the legends in both the Poetic Edda and the Nibelungenlied attempt to pull historical figures (Attila as well as others) into their narratives gave me the courage I needed to mix history and legend (and yes, some myth too) together into one big pot.

My protagonist Gudrun (or Guðrún or Kriemhild) comes from the legendary materials, and of course Attila hails from the historical. The main point of intersect between the legendary and the historical materials is that the legends lead us to believe that Gudrun marries and kills Attila, while Roman historians writing at the time of Attila say that Attila did in fact marry a Germanic woman just before his death, and she may have killed him. That is the only obvious tie between them, but that was good enough for me. I was ready to start building bridges back and forth between the legendary and historical materials on my own after that. By the time I was done, I felt rather like Schliemann must have when his shovel first struck Troy.

My other challenge in combining legendary and historical materials was dealing with the dragon. According to the legends, Sigurd, Gudrun’s true love, goes up into the mountains with a dwarf named Regan who walked the earth when the gods did, to slay a dragon who is actually Regan’s brother (post shape shift), to avenge the death of Regan’s father (whom the dragon brother killed) and retrieve the gold that the dwarf-dragon stole. Among the pieces in the hoard is a cursed sword. Because of these and other magical elements, The Last Wife of Attila the Hun could have been a fantasy easily enough. But I felt that the inclusion of such starkly fantastic elements side by side with starkly historical ones would be too great a contrast and make the whole hodgepodge less compelling. So I opted to render the dragon stuff realistic by having it happen “off stage.” The reader never “sees” the dragon. He or she, however, knows exactly what the dragon looks like because he or she is there when Sigurd comes down from the mountain after slaying the creature and tells Gudrun’s brothers all the wonderful details about his adventure. Nor does the reader ever get the skinny on the gods or the Valkyries or the long-living dwarves from me, the author. He or she gets these details direct from the characters, from their conversations.

A friend of mine who was married to a great artist once said of her husband, “For him, every object, whether it is a person or an animal or a lamppost, is either something he might want to include in a painting one day or something he can dismiss.” At the very best of times, that is what writing feels like to me. In the case of writing of The Last Wife of Attila the Hun, my “I must have that” moment began when I first read the legends in the Poetic Edda. I am not the first person to be mesmerized and inspired by these legends. Wagner, who would have read not the Poetic Edda but the Nibelungenlied, based his Ring Cycle on them. Tolkien borrowed heavily from them as well. And so have many other writers (and painters). The interesting thing to me is that no two “offshoots” look alike. Every version I am familiar with is different than every other one. It may be risky to mix legend/myth with historical events, but I’m glad I did so, because having the chance to immerse myself in these materials was literary bliss.

Joan Schweighardt

Writer/editor

GreyCore Literary Services

www.greycoreliteraryservices.com

facebook.com/GreyCore

www.joanschweighardt.com

https://www.facebook.com/joanschweighardtwriter

twitter@joanschwei

Published on October 30, 2015 06:00

October 23, 2015

Deep Secrets

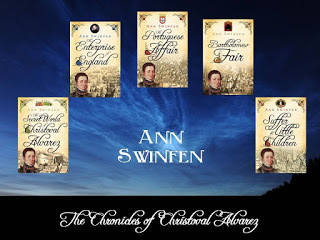

In February, I interviewed Ann Swinfen for New Books in Historical Fiction and blogged about it, as I usually do, a few days later. In the interview, we discussed her lovely The Testament of Mariam and, in passing, her latest novel This Rough Ocean. Her five-part (to date) series The Chronicles of Christoval Alvarez got barely a mention, although even then I intended to read it. The series is, after all, set in the sixteenth century.

In February, I interviewed Ann Swinfen for New Books in Historical Fiction and blogged about it, as I usually do, a few days later. In the interview, we discussed her lovely The Testament of Mariam and, in passing, her latest novel This Rough Ocean. Her five-part (to date) series The Chronicles of Christoval Alvarez got barely a mention, although even then I intended to read it. The series is, after all, set in the sixteenth century.Well, life went on, and as so often happens, Christoval took a back seat to other interviews and GoodReads challenges and my own Swan Princess, now nearing the end of draft 2. It was early this month before I picked up The Secret World of Christoval Alvarez as part of a full set, in part because I discovered that Christoval, known to friends and family as Kit, will be heading to Muscovy soon. When I learned Kit’s real secret, with its parallels to my Nasan, I couldn’t resist. And since I wanted to be prepared, I decided, as they say, to begin at the beginning. Within twenty pages, I was in love with the series. So this is one of my rare Hidden Gems posts. Definitely, seek out these books without delay.

The series begins in 1586. Elizabeth I has been on the throne for almost thirty years, and from the point of view of the schoolchildren we once were, life should be good. No more religious wars under Gloriana, right? No worries among the Protestants that the Catholics will come back in force and burn everyone, no fear among the Catholics that they will be accused of treason en masse and sent to the stake, no conspiracies to get Elizabeth off the throne in favor of a king or just a different ruler more to some ambitious subject’s liking?

Well, not quite. In fact, in what would be sure to cast dismay into the souls of kids everywhere if they knew, Elizabeth’s hold on the scepter remained shaky through much, if not most, of her reign. The Spanish wanted England, the French wanted England, the Scots wanted England, and there were factions within the country willing and eager to back anyone but the queen. Most of the factions had some religious motivation, given the culture of the day, but religion was often a justification and cover for naked power plays, then as now. Specifically in 1586 the Spaniards—whose king believed he had a right to the English throne by virtue of his marriage to Mary Tudor and who were in general feeling their oats because of their victories in the New World and, more recently, over Portugal—were planning to bring their Inquisition across the English Channel by any means available. (In Christoval 2, The Enterprise of England, they hit on the idea of a mighty armada.) Meanwhile, the French were placing their hopes on Mary Queen of Scots, whom Elizabeth had under house arrest but was reluctant to execute due to the precedent it would set.

In this fraught atmosphere, sixteen-year-old Kit Alvarez, a refugee from Portugal and the only surviving child of a once-wealthy Jewish family that converted to Christianity to avoid the Inquisitorial flames, wants nothing more than to become a scholar and physician like his father. For reasons that are revealed early on, formal university training is out of bounds for Kit, but an apprenticeship at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London offers a worthy alternative—until Kit’s skill at math comes to the attention of Sir Francis Walsingham. Queen Elizabeth’s chief spy master needs a skilled code breaker fluent in Spanish and French to crack the ciphered messages his agents are intercepting between the court in Paris and Mary Queen of Scots’ luxurious prison. He selects Kit for the job, and since his sphere of influence extends to the hospital, Kit has little choice but to accept. With raw memories of Catholic forces invading Portugal, Kit soon embraces the new mission while trying to juggle commitments to father, hospital, and state. But the last thing he really wants in life is another set of secrets to protect.

Kit is a charming and fascinating character, beautifully developed, the story full of interesting twists, and the writing (as in The Testament of Mariam) lively and original. As I do for the books whose authors I interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, here I’ll quote the first paragraph to whet your appetite. See how quickly the sense of a personality, a time, a place, and a problem are established. A Hidden Gem indeed!

“I was washing alembics when he came. Often, in the months and years that followed, I wondered how things might have turned out, had I been away from home. My father had been summoned to one of his private patients and I had pleaded to go with him to the great man’s house, for I had never even stepped over the threshold of the mansion in the Strand, but the winter had been severe, we were short of many remedies, and I must stay at home and wash the alembics so that we might spend the evening distilling. I did not like being alone in the house, with the dark afternoon heavy in the sky outside, and chill draughts plucking at the back of my neck like the unforgiving fingers of the dead. The old timbers of the house swayed and creaked and moaned in the wind.”

And congratulations to fellow Five Directions Press author Courtney J. Hall, whose debut novel, Some Rise by Sin, is now a Book Muse Recommended Read!

Published on October 23, 2015 06:00