C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 41

July 22, 2016

Cooking in the Klondike

Last week I wrote about “food for bookworms.” Well, this week the food is real, not virtual. What could be better than a novel with recipes, especially mouthwatering pastries and pies? I can feel my waistline expanding just from reading about the gingerbread, fritters, and corn pudding that form the background to Eliza Waite, subject of my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview.

Last week I wrote about “food for bookworms.” Well, this week the food is real, not virtual. What could be better than a novel with recipes, especially mouthwatering pastries and pies? I can feel my waistline expanding just from reading about the gingerbread, fritters, and corn pudding that form the background to Eliza Waite, subject of my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview. Now, don’t misunderstand me. I chose to interview Ashley E. Sweeney about her debut novel because I liked the idea of a woman resourceful enough to live alone on an island in the Pacific Northwest, then travel north to Alaska in the heyday of the Klondike gold rush. It’s a great story, and the author tells it well.

But I also love to cook. I once translated a medieval Russian guide to household management that has become a staple on the reenactment circuit, and I own more cookbooks than any reasonable person could hope to work her way through in a lifetime. I have to stash the less-used ones in the basement and the garage because the kitchen shelves are groaning under the weight. So I must admit the news that the book contained nineteenth-century recipes caught my attention as well.

And what recipes they are—checked and adjusted for twenty-first-century kitchens by a dedicated team whom the author thanks by name, they retain the original phrasing but, unlike many older recipes, include measurements that a contemporary cook can understand. The recipe file in the back focuses on savories, including various soups, omelets and fried potatoes, Welsh rarebit and Egg (that is, French) Toast.

In the book, Eliza often has to substitute. Eggs have become a scarce commodity since she had to eat her chickens, and only trips to the mainland in a rowboat keep her in flour, sugar, and saleratus (baking powder). But Eliza adjusts—and survives.

In Alaska, she opens a bakery, and here the recipes really come into their own. (What, you thought she would chase after gold? Not our Eliza—she’s not so foolish. Besides, in Skagway, not far from Juneau, gold flakes drift down from the sky. No need to climb a sheer cliff twenty times with supplies and trek to the goldfields across miles of ice and snow.) Pecan tarts and apple pie and a sort of nineteenth-century trail mix that Eliza dubs miner’s snickerdoodles keep her busy from dawn to dusk. So whip up a batch of cinnamon buns or glazed doughnuts and settle in. You can listen to the interview at the same time.

If you’re looking for me, you’ll find me in the kitchen. Meanwhile, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Cypress Island, September 1896: a tragedy has left a young widow, mourning her child, living alone in a cabin on this isolated spot near Bellingham Bay in the very new state of Washington. Once a month or so, Eliza Waite rows two hours each way to the general store on the mainland for supplies. Otherwise, she supports herself through hard work: chopping wood, maintaining a vegetable garden, fishing, cooking, doing laundry. Each day has a chore, and they repeat endlessly until a second crisis and a lucky find send Eliza northward on a boat to Alaska, where the Klondike gold rush is at its height. There the strands of her past interweave in ways she could not have anticipated.

In Eliza Waite (She Writes Press, 2016), Ashley E. Sweeney creates a tough, resilient, likable heroine whose compelling story will draw you in and make you pull for her success. And if all this effort makes you hungry, have no fear: the book is filled with Eliza’s recipes, and a plate of gingerbread or miner’s snickerdoodles is never far away.

Published on July 22, 2016 06:00

July 15, 2016

Food for Bookworms

Summer is the time for beach reads, winter for curling up with a good book before a roaring fire. For true bookworms, of course, time of year makes no difference: “spring, summer, winter, or fall,” as the song goes, a good story calls to us no matter when or where.

Summer is the time for beach reads, winter for curling up with a good book before a roaring fire. For true bookworms, of course, time of year makes no difference: “spring, summer, winter, or fall,” as the song goes, a good story calls to us no matter when or where. When we at Five Directions Press named our quarterly newsletter Books Worth Reading, we had in mind primarily our own. Do, by all means, give some of ours a try. Joan Schweighardt’s The Last Wife of Attila the Hun—rescued from the now-defunct Booktrope Editions, reformatted, and reissued—became available again in print and for Kindle at the end of June. C. P. Lesley’s The Swan Princess, third of her Legends of the Five Directions, appeared in mid-April. And in less than three weeks we plan to release Gabrielle Mathieu’s debut historical fantasy novel, The Falcon Flies Alone. For more information on these and our other novels/memoirs, see our Books page.

Those three should appeal to lovers of historical fiction and historical fantasy. Several contemporary novels, general fiction and romance, will appear through the fall and winter months and into next year. But the site also offers descriptions, excerpts (online and audio), reviews, awards, and previews for older books in our chosen genres: contemporary fiction, including romance; historical fiction, science fiction, and fantasy with and without romantic elements; and memoirs. Most of our books are aimed at women and girls 14 and up, but not all. And men like them as well.

A quarterly newsletter leaves a lot of months uncovered, so at the beginning of this year we decided to fill in the blanks. To spare our subscribers’ in boxes, we post monthly to our blog a short list of books we loved. Some are indie-published, others commercial; most recent, some not. The only criterion for inclusion is that at least one member of our coop loved them. You can get a sense of the posts below and at Five Directions Press. There you can sign up for our newsletter, which includes interviews with authors, press news, and access to coloring pages associated with our books, drawn by the talented Ariadne Apostolou. You can also browse prior months’ posts and check back for new ones; usually they go up around the fifteenth of each month.

The rest of this post echoes the blog. Initials indicate the 5DP author who loved the book.

Dot Hutchison, The Butterfly Garden (Thomas & Mercer, 2016)

Not for the faint of heart, The Butterfly Garden is creepy crime fiction reminiscent of a Criminal Minds episode. The story, told both from the present from the point of view of FBI agents and in flashbacks from the main character, a kidnapped young woman, takes the reader along as the characters unravel the mystery surrounding a serial kidnapper, the secret garden he's built and the women he calls his Butterflies.—CJH

Christiane Ritter, Woman in the Polar Night (repr. University of Alaska Press, 2010)

A first-person account of a year in the frozen north, continuously in print since 1938 and still a compelling read. A well-to-do Austrian Hausfrau and artist leaves her child and her ordered, comfortable life to join her husband and a Norwegian hunter in a tiny cabin on an island in the Arctic Sea. There she finds beauty in the ethereal light of the polar sky, the furious storms, the “mighty jagged arches and towers of ice” and the wild and mighty animals: polar bears and seals, reindeer and arctic foxes.—DS

Tricia Sullivan, Occupy Me (Gollancz, 2016)

A lofty mixture of physics and poetry, this novel is about an angel from another dimension working for The Resistance, which tries to make life better in small ways. But the members of the Resistance aren’t who they seem to be, and Pearl, the angel, is an enigma—a huge, compassionate entity who doesn’t know her own origin. The more you read about the main characters, a doctor who is possessed by a murderous entity that may actually be trying to save the world and an angel who was created out of “extinct animals and nano-libraries,” the less you actually know them. As the author says at one point, “I didn’t recognize myself. Never again the same. In my brain a thicket of dendrites were standing on end in dark and terrible welcome.” Read this book, and your dendrites will hop to attention as well.—GM

Beatriz Williams, A Certain Age (William Morris, 2016)

A wealthy 1920s socialite who has an “understanding” with her philandering husband falls in love with a man twenty years younger than she is. Life looks good until her brother enlists her young lover to issue a marriage proposal on his behalf, creating a love pentangle that ends in a courtroom and scandal. Beatriz Williams’s ability to draw us into her story by rendering every one of these not always admirable characters sympathetic and believable makes this novel a must-read.—CPL

Published on July 15, 2016 06:00

July 8, 2016

The Heirs of Melusine

In my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, I talk with Hana Samek Norton, author of

The Sixth Surrender

and

The Serpent’s Crown

. We are both historians by training and inclination, and we talk a lot about history and where historical fiction fits into what we might call the range of ways to approach history, in this case through entertainment. But our initial focus on facts and documents will not, I hope, obscure the reality that these are first and foremost great stories with fascinating and well-developed characters who move seamlessly in and out of the historical environment to which they have been assigned. And oh, yes, that cover is gorgeous.

In my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, I talk with Hana Samek Norton, author of

The Sixth Surrender

and

The Serpent’s Crown

. We are both historians by training and inclination, and we talk a lot about history and where historical fiction fits into what we might call the range of ways to approach history, in this case through entertainment. But our initial focus on facts and documents will not, I hope, obscure the reality that these are first and foremost great stories with fascinating and well-developed characters who move seamlessly in and out of the historical environment to which they have been assigned. And oh, yes, that cover is gorgeous.Guérin de Lasalle, former leader of a band of mercenaries, has quite mixed feelings about the marriage into which his service for Eleanor of Aquitaine has pitchforked him; and his doubts are more than matched by his educated, pious, and somewhat mousy wife, Juliana. At the beginning of The Serpent’s Crown, Guérin allows himself to be lured back to the Holy Land, leaving Juliana behind. But when her father-in-law forcibly removes her child from her custody, Juliana sets out in search of her husband, hoping he can help her reclaim their daughter.

The rich emotional framework of these books utilizes the real and imagined history of the barons de Lusignan, descended—by their own account—from the half-serpent/half-woman Melusine. In a variant of the Cupid and Psyche (and, coincidentally, Swan Maiden) myth, Melusine’s husband fails to keep his promise to trust her, and she flees their home, returning only to wail for her children during every windy, stormy night. Her heirs establish a reputation for duplicity and valor, loyalty and rebellion, competence and scheming. The politics of France, England, Cyprus, Jerusalem, and Armenia are changed as a result.

The rest of this post, as always, comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

In the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, the grip of European knights on the Holy Land has begun to loosen. The Muslim forces under Saladin have won a major victory, and the crusaders have so far forgotten themselves as to besiege, then sack, the imperial Christian city of Constantinople—their nominal allies. In the confusion thus created, two warring clans—the Lusignans and the Ibelins—at times cooperate but more often compete for supremacy, spurred on by the marital and political maneuvering of Maria Komnene, queen of Jerusalem. The conflict expands to include Cyprus, Armenia, the Levant, and the Eastern Roman Empire as a whole.

The plots and counterplots sweep up Juliana de Charnais, in distant Poitou. The legitimacy of her marriage is in question, a male relative captures her daughter, and her unsatisfactory husband has chosen to obey another relative’s summons to defend the Lusignan cause in the east.

To reclaim her child, Juliana follows her husband. A former novice, Juliana seeks first and foremost to remain true to her conscience. But in a world where assassins lurk in every corner, just staying alive may prove enough of a challenge.

From central France to Nicosia and Jerusalem, Hana Samek Norton weaves a rich and fascinating tapestry of love, loss, loyalty, betrayal, and deceit. Fans of Dorothy Dunnett’s sweeping historical sagas should not miss The Sixth Surrender and its sequel, The Serpent’s Crown (Cuidono Press, 2015).

Published on July 08, 2016 06:30

July 1, 2016

The Bookshelf

It’s good to be popular. Interest in the New Books Network has grown to the point where I can barely keep up with the requests for podcast interviews and even blog posts. And know that I deeply appreciate that, since without guests willing to talk, an interview series soon dies. At the same time, there are only so many hours in the day. As a result, I’ve decided to start a new monthly feature on this blog: the Bookshelf. Whenever I can, I will read the books and post about them—even interview the authors. But at a minimum, I can list titles that appeal to me, even if they are not historical fiction or reach me at a time when the schedule is already full.

It’s good to be popular. Interest in the New Books Network has grown to the point where I can barely keep up with the requests for podcast interviews and even blog posts. And know that I deeply appreciate that, since without guests willing to talk, an interview series soon dies. At the same time, there are only so many hours in the day. As a result, I’ve decided to start a new monthly feature on this blog: the Bookshelf. Whenever I can, I will read the books and post about them—even interview the authors. But at a minimum, I can list titles that appeal to me, even if they are not historical fiction or reach me at a time when the schedule is already full.This month’s list includes, in alphabetical order:

Alix Hawley, All True Not a Lie in It (a different look at Daniel Boone)

Catherina Ingelman-Sundberg, The Little Old Lady Who Broke All the Rules (not historical fiction, but it looks like a fun summer read)

Dorothy Love, Mrs. Lee and Mrs. Gray (female friendship during the US Civil War)

Antonio Manzini, Black Run (modern detective novel set in the Italian Alps)

Wilbur Smith, Desert God and Golden Lion (two novels by a bestselling author [the second with Giles Kristian] sent to me a while ago—ancient Egypt and the Sultanate of Zanzibar—they both seem fascinating, but the author doesn’t interview and I haven’t quite managed time to read them, although I will)

Beatriz Williams, A Certain Age (fun and games in Jazz Age Manhattan—stay tuned for a Q&A with this author in two weeks)

And last but not least, and not in alphabetical order, Mary Hogan, The Woman in the Photo . Her publicist sent me this Q&A, and I really enjoyed what I’ve read so far. So read on to find out more about this book. Normally I would have drawn the questions up myself, but I would have asked the same ones....

What’s the story behind The Woman in the Photo? How did the book come to be?

I first had the idea for this book 24 years ago! I’m not kidding. In 1992, my husband, actor Robert Hogan, was in an off-Broadway play called On the Bum, also starring Cynthia Nixon and Campbell Scott. The play was set in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, several years after the epic flood. The characters talked about a “lake in the sky” which piqued my curiosity. A few days later, I went to the library to read about such strange geography. That’s when I read the real story of the Johnstown disaster. Wow. I was blown away. What a great story! I held my breath for 24 years worrying that someone would write my book before I got a chance to. There are other books out there about the flood, but nothing like mine.

How did you conduct your research for the book? Are any of the characters in the book inspired by real-life people?

While on book tour in Pittsburgh for my first young adult novel, The Serious Kiss, I had a free afternoon. So, I rented a car and drove two hours to Johnstown to see it for myself. I could have stayed there for two weeks. There was so much of interest for this Californian girl. Over the years, I would visit twice more. Generously, the President of the Johnstown Heritage Association gave me a day-long tour of everything I needed to tell a compelling tale, including access to the inside of the private Clubhouse which is still standing! Aside from the very real members of the exclusive club: steel titans Andrew Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, bankers like Andrew Mellon, U.S. Senator and Attorney General Philander Knox, all the characters are fiction.

How was the writing experience for The Woman in the Photo different from your experience writing your previous novel, Two Sisters?

Two Sisters was a process of opening up my heart and spilling its contents onto the page. Inspired by the early death of my older sister, I told a tale of family secrets that I knew all too well. Writing The Woman in the Photo was a completely different experience. First, I read a gazillion historical novels. Then, I read every book I could find about Johnstown. I even read a novel called Annie Kilburn that was written in 1889 to get a feel for the language of the day. Research, research, research. I was told that women who read historical fiction are fiends about accurate detail. So, my biggest fear about creating a main character who was an upper-class woman of the nineteenth century was getting her many corsets right.

Both The Woman in the Photo and Two Sisters center around female relationships. Why do you think readers are so fascinated by the bonds between female family members?

Ah, yes. Those bonds are complicated, indeed. I have yet to meet a woman who didn’t have a knotty relationship with her sister or her mother. Even when they are smooth, they are bumpy. In my case, my mother and I were very much alike, and my sister and I were very different. So there were a lot of crossed wires. We hurt each other even when we didn’t know it. My dad and my brothers sort of kept their heads down and watched sports :)

For me, the best characters are flawed, striving, loving, selfish, feeling, reacting, deep, curious, furious, and worried—mostly—about their hair. In other words: women.

Is there a particular message you hope readers will take away from The Woman in the Photo?

One of the themes of this novel is: Is DNA your destiny? Are you born to be who you are? Or, can life itself mold you? I would love for readers to finish The Woman in the Photo with the sense that we are all on this earth to be kind to one another. To live together. Even on bad hair days.

Thanks for joining me—and stay tuned for future lists of books worth watching.

Published on July 01, 2016 06:00

June 24, 2016

Dancing at the Savoy

A couple of weeks ago, in “The Fog of War,” I wrote about the long-term, often under-appreciated effects of the First World War. In that post, I promised to feature written Q&A interviews with several of the authors now writing novels set in the 1910s and 1920s, beginning with Hazel Gaynor, whose

The Girl from The Savoy

was sent to me for an interview at a time when I had no room in my schedule. I loved the novel, and I was delighted when Hazel agreed to answer my questions. The book went on sale June 7, so don’t miss it or her website, where you can find out more about her and her previous novels.

A couple of weeks ago, in “The Fog of War,” I wrote about the long-term, often under-appreciated effects of the First World War. In that post, I promised to feature written Q&A interviews with several of the authors now writing novels set in the 1910s and 1920s, beginning with Hazel Gaynor, whose

The Girl from The Savoy

was sent to me for an interview at a time when I had no room in my schedule. I loved the novel, and I was delighted when Hazel agreed to answer my questions. The book went on sale June 7, so don’t miss it or her website, where you can find out more about her and her previous novels.My questions are in bold.

What drew you to the story that became The Girl from The Savoy?

The idea came about through a discussion with my editor. We both love the 1920s and I was fascinated by the idea of an ordinary working girl who longed for a better life and who had access to the famous actresses she so admired. The dazzling social scene of London’s iconic hotels during the era felt like the perfect setting for that scenario. When I started researching the history of The Savoy Hotel I found so many wonderful stories of famous people who had dined and stayed there. I imagined the young chambermaids gossiping about the hotel’s guests in their room late at night, and the story developed from there.

Tell us about Dolly, your central character—and Loretta, who is in a way her counterpart but has in other ways led a very different life.

The Girl from The Savoy tells the story of two women from very different social backgrounds: Dolly Lane, a chambermaid at London’s iconic Savoy Hotel, and Loretta May, a famous actress in the West End. Both are struggling in the aftermath of the Great War, which has left them with secrets and regrets. Dolly is a gutsy, plucky heroine who dreams of a better life for herself. I had such fun writing her. She feels like a real person to me now, and I hope readers will be rooting for her! Loretta’s privileged life is so different to Dolly’s, but when they meet we realize that they are perhaps not so very different after all. I loved writing the exchanges between them.

You have two previous novels, A Memory of Violets and The Girl Who Came Home. Where does The Girl from The Savoy fit in that trajectory—or does it?

There is no link between the three novels, other than that they are all historical. I’m fascinated by the way people lived in the past, and by the incredible life-changing events that took place in the last 100 years. Often it’s an image from the era, or a person or event I read about that first ignites the creative spark, then I let my imagination take over. My first novel was inspired by the Irish connections to the Titanic; my second by the flower sellers of Covent Garden in Victorian London. The Girl from The Savoy took me into the years of the Great War and the early 1920s, which were both new periods/events for me to write about. I suppose it makes sense that my writing has moved forward a little in time period with this latest novel.

World War I, known then as the Great War, is a looming presence in this novel. Everyone is struggling, in some way, to cope with their experiences during the war or the effects (sometimes indirect) of the war. What made you decide to approach your story in this way?

During the early 1920s, women’s roles were changing dramatically. War had opened their eyes to new experiences and for many it was nearly impossible to return to a life in domestic service after the relative freedoms of factory or office work. For the social elite, the war had also challenged the accepted social norms for young ladies. Many had worked as nurses and experienced life outside the stuffy confines of their privileged existence for the first time. With the suffragettes fighting for the vote and many women having to manage without their husbands and sons who had never returned, this was a real period of social change and that always allows for great story. The Great War was such a life-changing event that it was impossible to write a novel set in the years directly after it without acknowledging the impact it had on everyone’s lives.

What would you like readers to take away from The Girl from The Savoy?

Every reader will take something different from every book, so in a way, it’s really not for me to say! When I read, I love discovering something I didn’t know much —or anything—about, so I hope my readers will experience that through my characters and the historical settings I place them in. Ultimately, I want my books to create an emotional response in the reader as they forget about real life for a while and step into my fictional world. All any writer can do is write from their heart and hope that readers will connect in some way with what they have done.

What are you working on now?

I have two exciting projects underway at the moment!

My fourth novel (as yet untitled) is inspired by the true events surrounding two young cousins who claimed to photograph fairies in the village of Cottingley in Yorkshire in the 1900s and convinced men such as Arthur Conan Doyle of their authenticity. Growing up in Yorkshire, this is a story I have always been aware of and one I cannot wait to share. The novel will be published in spring/summer 2017.

My other project is a historical novel Last Christmas in Paris, which I am co-writing with the author of Becoming Josephine and Rodin’s Lover, Heather Webb. The novel is a love story—written in letters—about a young English woman and a soldier who promise to spend Christmas together in Paris until the Great War sends them on different paths. It’s such a great experience writing this with Heather. It will be published in fall 2017.

Published on June 24, 2016 06:00

June 17, 2016

Heroes on Pedestals

For some reason, we subconsciously expect our heroes to be perfect—or at least free of major flaws. Perhaps it is a relic of childhood adoration of the father, a wish fulfillment that we ourselves might attain perfection, or even an unexpected outcome of the universal human love of story. Whether the hero in question is an athlete or a musician, a statesman or a soldier, we find it upsetting to discover that the great man has feet of clay. Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence, but his regard for human rights did not keep him from abusing his fourteen-year-old slave girl—who existed outside his categories of those entitled to rights, since she was simultaneously female, African-American, and (in his mind) property.

For some reason, we subconsciously expect our heroes to be perfect—or at least free of major flaws. Perhaps it is a relic of childhood adoration of the father, a wish fulfillment that we ourselves might attain perfection, or even an unexpected outcome of the universal human love of story. Whether the hero in question is an athlete or a musician, a statesman or a soldier, we find it upsetting to discover that the great man has feet of clay. Thomas Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence, but his regard for human rights did not keep him from abusing his fourteen-year-old slave girl—who existed outside his categories of those entitled to rights, since she was simultaneously female, African-American, and (in his mind) property. Nor was Jefferson alone in his contradictions. Woodrow Wilson argued for the rights of ethnic minorities yet made racist comments about W. E. B. Dubois. Cecil Rhodes held a dim view of those under his colonial governance. And Johann Sebastian, like most religious Protestants of his day, expressed antisemitic views on more than one occasion, including in his choral pieces.

Curiously, heroines tend not to attract this kind of unconditional adoration. As I noted in “First, but not Equal,” female celebrities, especially women in power, more often suffer from slurs on their characters and allegations of adultery, scheming, and murder. That’s why I talked about fathers and great men, above.

Of course, times change, and standards change with them. The present exhibits plenty of unfortunate attitudes and behaviors, and the past even more so. Our task is to acknowledge both the virtues and the flaws in our heroes—to see them, perhaps, as evidence of how far we have progressed and how far we have yet to travel. As Lauren Belfer notes in my most recent interview, the question for us is how to interpret flawed genius and react to it. In Bach’s case, the music remains beautiful even when the libretto repels. We must find a way to respect the brilliance of the first as we reject the hatred implicit in the second.

The rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

It’s May 1945, and a pair of American GIs in occupied Germany find themselves at what appears to be an abandoned estate. When they enter, they discover a resident, reduced to burning valuable books for fuel. Within an hour, the resident is dead and the GIs are speeding back to their camp, a few “souvenirs” in their rucksacks.

So begins And After the Fire , the new book from bestselling author Lauren Belfer, whose previous forays into historical fiction include City of Light and A Fierce Radiance. Through the independent but intertwined stories of Susanna Kessler and Sara Levy, Belfer’s third novel explores, among other things, the long history of antisemitism in Europe, beginning in late eighteenth-century Berlin and ending in twenty-first-century Manhattan. The link between Susanna, Sara, and the fleeing GIs is a previously undiscovered cantata by Johann Sebastian Bach, hidden for three centuries because of its offensive and inflammatory libretto.

Bach’s missing cantata is fictional, but the questions it raises are very much part of today’s headlines. How do we deal with the reality that greatness and intolerance can exist side by side? How do we cope with the unpleasant relics of our own past? For this reason—and for its compelling portrayal of Susanna and Sara, so alike yet so different, in part because of the times in which they live—And After the Fire is a novel not to be missed.

On another note, the four-way post on writing historical fiction that I mentioned last week is now up on the Writer’s Digest blog: Brian Klems, “The Writer’s Dig.” You can find my full original post, with links to the others, at “Party All the Time.” The mixture of styles and approaches is quite fascinating. Thanks to all those involved—especially Brian, for agreeing to publish us, and Kristen Harnisch, for convincing him.

Published on June 17, 2016 10:16

June 10, 2016

Best-Laid Plans

Once in a while, things don’t work out as planned. Shocking, I know. I’m sure it never happens to you. And I’m so darned organized, it always amazes me when it happens to me. But sometimes it does.

Today’s slot was supposed to be a Q&A with an author whose book I loved. That’s still underway, and I’m sure it will come through, but life—more accurately work—got in the way and I was late sending out questions. My next New Books in Historical Fiction interview, with Lauren Belfer about her new novel And After the Fire, took place this morning—and came out really well—but even the indefatigable Marshall Poe can’t turn 500 MB of audio into a workable MP3 file at the drop of a hat. So look forward to that link and discussion next week.

For a while, I thought I had a backup in the group post I wrote about back on March 31, “Party All the Time.” It’s due to go up on Brian Klems’ The Writer’s Dig any day, but apparently it hasn’t yet. As a result, here I am late into Friday without a proper post to share.

One small piece of Five Directions Press news: our own Ariadne Apostolou has revealed a hidden talent (known to her, of course, but previously not displayed to us) and produced the first of what we hope we will be a series of adult coloring pages for her fellow authors at the press. The Legends of the Five Directions series are first, and I can attest that they are gorgeous. To download your copies, all you need to do is subscribe to our quarterly newsletter by going to the opener page at http://www.fivedirectionspress.com. The link will be in your welcome letter.

Otherwise, to cut a long story short, I can only write a “treading water” post this week. But no fear, I’ll be back next Friday with bells on, as they say. In the meantime, I hope everyone has a wonderful week!

Published on June 10, 2016 12:57

June 3, 2016

The Fog of War

A century ago, what was then known as the Great War was in full swing. Young men were dying by the hundreds and thousands in trenches dug into the poppy fields of Flanders, and the initial sense that the war would be over by Christmas had long since vanished in a fog of despair. Even by the standards of war, where overweening ambition too often clashes with unrealistic expectations, the First World War was a tragedy: a conflict that need never have happened, spurred on by contending imperialist powers that overestimated their own capacity to conduct diplomacy and blundered their way into a crisis.

A century ago, what was then known as the Great War was in full swing. Young men were dying by the hundreds and thousands in trenches dug into the poppy fields of Flanders, and the initial sense that the war would be over by Christmas had long since vanished in a fog of despair. Even by the standards of war, where overweening ambition too often clashes with unrealistic expectations, the First World War was a tragedy: a conflict that need never have happened, spurred on by contending imperialist powers that overestimated their own capacity to conduct diplomacy and blundered their way into a crisis.Today the First World War is almost forgotten—in part because no one now alive fought in it, in part because the even more massive conflagration of the Second swept over it and obliterated it as it obliterated half of Europe and great swaths of Asia. Yet the Great War destroyed an entire generation of young men, rippling through the economy and society, opening doors for women, ushering in the almost manic euphoria of the 1920s. Its effects on the culture were every bit as far-reaching as the events of 1939–45—for which, of course, it laid the groundwork.

Perhaps because of the centennial—or perhaps by chance, in one of those coincidences that at times sweep the world of publishing in one direction or another—over the past year I have seen a renewal of fictional interest in the first three decades of the twentieth century. The last three months alone have brought to my attention no less than four novels set in this period: Laini Giles’ The Forgotten Flapper , Kathleen Tessaro’s Rare Objects , Hazel Gaynor’s The Girl from the Savoy, and, just yesterday, A Certain Age by Beatriz Williams. For more on the first two, click the links in their titles. Hazel Gaynor has graciously agreed to answer questions; with luck, her answers will appear this time next week. A Certain Age is not due for release until July, so I will write more about it then.

Two other recent titles—Cat Winters’ The Uninvited and Anita Diamant’s The Boston Girl—also explore the after-effects of the war, especially the great influenza epidemic of 1918. In addition, several long-running series—most notably, Laurie R. King’s Russell and Holmes and Touchstone books—take place in the 1920s. There, too, the Great War and its aftermath appear in ways both overt and covert.

Is this the beginning of a trend, or just a blip on the fictional radar screen? There is no way to tell from this vantage point. But the Great War has been ignored for too long. It is past time we remembered it—if only so that we don’t find ourselves repeating its mistakes.

Published on June 03, 2016 05:59

May 27, 2016

Scots Wha Hae

As I’ve mentioned before, my New Books in Historical Fiction schedule has become crowded to the point where I can’t feature all the authors and books I would like to include.

Antonia Barclay and Her Scottish Claymore

is one such book.

As I’ve mentioned before, my New Books in Historical Fiction schedule has become crowded to the point where I can’t feature all the authors and books I would like to include.

Antonia Barclay and Her Scottish Claymore

is one such book.Historical fiction combined with parody and an irreverent approach to both the past and romance, Antonia Barclay and Her Scottish Claymore tells the rollicking story of a memorable heroine in sparkling and often funny prose. I always enjoy a witty romance, and this one delivers, starting with the title. Jane Carter Barrett was kind enough to let me pepper her with written questions, so while we don’t have the full fifty-minute interview here, we do hit the highlights. For more information on Jane and her story, see her website. And thank you, Jane, for sharing your thoughts with us here!

How did you decide to start writing fiction?

I began writing in college and continued in law school, but it was mainly technical writing, which wasn’t much fun and didn’t allow for a whole lot of creativity. Eventually, I experimented with writing fiction and discovered it was much more enjoyable. Besides Antonia, I have written one other book (which I’m shopping around right now to publish), started the sequel to Antonia, and also started a legal thriller set in Texas.

And how did Antonía Barclay and her story come to you? Do you have a Scottish background, or a particular interest in Scotland?

After reading all I could find on Mary Queen of Scots, I found myself wishing that Mary had had a daughter. Consequently, I created the character of Antonia Barclay (Mary’s “should’ve been” daughter), and from that point the plot and other characters more or less spontaneously combusted in my brain. Naturally, Antonía had to resemble Mary in some ways, and this is the reason for Antonía’s lofty stature, independent spirit, and aptitude for riding. However, for plot purposes, Antonía could not be a dead ringer in terms of appearance, and thus Antonía did not inherit her mother’s trademark red hair and amber eyes. So it’s not necessarily that I wanted Antonía to be Mary’s daughter, but rather I desperately wanted Mary to have a daughter, to have had a daughter. And at this juncture, you can probably tell that I have to remind myself that Antonía is not an authentic historical figure, merely a figment of my imagination, but imagining will always make her real to me. And, of course, there’s always the off chance that history got it wrong, that Mary really did have a daughter, and Antonía really did exist.

And yes, my grandmother was born and raised near Kirriemuir so I’ve had a lifelong fascination with Scotland and the Scots!

Tell us about Antonía—and her Claymore—as personalities.

Breck Claymore was unequivocally the most challenging character for me to create, because he is a man of quiet dignity and by definition he couldn’t do a whole lot of talking. His calm solidity, stoic determination, and integrity had to be conveyed through action, not words; thus his dialogue could be neither lengthy nor abundant. The novel is Antonía’s story from beginning to end, and I tried to insinuate Mr. Claymore into it without eclipsing her light while also maintaining his strength of character. He had to possess both alpha and beta male characteristics in order to attract Antonía’s attention initially, and then as their relationship develops, he draws on these same characteristics to cope with her strong-willed and high-spirited nature. As a result, I made Mr. Claymore a self-made man with a job, a fortune, and a set of seriously broad shoulders. But despite Mr. Claymore’s fine qualities and his magnificent male musculature, he had roamed the Scottish countryside for nearly three decades without finding a woman worth marrying. Until, of course, he crosses paths with Miss Barclay. I’m not certain if I achieved my objective here, but I attempted to cultivate a new breed of man: The Alpheta Male. A man sufficiently secure and confident in his masculinity to view a woman as an equal partner in all respects, a man willing to relinquish both calling the shots and claiming the top position as a matter of course.

I was amused to see that you make an explicit pact with your readers, up front, not to get upset over anachronisms. Why is that?

The last thing I wanted in writing this book was to offend hardcore historical fiction readers who expect extremely accurate representations of particular time periods. I have tremendous respect for the historical fiction genre and did not want to confuse or anger people who started to read what they thought was pure historical fiction only to discover that Antonia Barclay also contains elements of soft parody and romantic comedy. So to avoid any misunderstanding from the outset of the book, I decided to include a caveat explaining that while the story has plenty of romance and adventure, it also has its fair share of modern-day allusions, irreverent humor, and a certain degree of incorrectness.

What would you like readers to take away from “Antonia Barclay and Her Scottish Claymore”?

Tenacity, perseverance, and self-reliance are probably not personality traits that were desired, instilled, or encouraged in the sixteenth-century young woman. But Antonía doesn’t care one whit what others think of her or what is expected of someone of her gender and social class. She trusts herself and is secure in herself. No swooning, kowtowing, or boohooing for her. Antonía is a tough critical thinker who is often contrary to the point of being a pain in the neck, but that’s who she is and if the entire world knows it so much the better. Suffering fools gladly and squandering time are not her deals. She makes no apologies for being herself, and when she sets goals she sticks to them, despite the obstacles and her own limitations. But having spouted all that platitudinous wisdom, I hope readers simply enjoy escaping to another time and place and enjoy the mix of fact and fiction.

What are you working on now?

As mentioned above, I’m working on two new books as well as attempting to find a publisher for my reently completed book called Thru the Iroquois Sky, which is more in the realm of the “New Adult” genre. If you’re interested here’s the synopsis:

Thru the Iroquois Sky is the story of a talented young athlete with bright prospects and boundless opportunities in front of him. In the spring of 1977, an extra layer of happiness is added to his already abundant supply of achievements and blessings. A quiet, introspective musician walks into his life and into his heart. Ben Longhouse is instantly smitten and immediately goes to work to make Evie St. Clair his own. He introduces her to his friends, his family, and his world as an assimilated Iroquois Indian. In turn, it doesn’t take long for Evie to become thoroughly enchanted with Ben’s sweet charm, selfless generosity, and lovable nature. To those who know the young couple, their future seems destined for success. But fate often has its own agenda.

On another note altogether, Five Directions Press’s very talented cover designer, Courtney J. Hall, has turned her hand to updating the cover for The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel. You can see the results in the sidebar. The text is the same, except for some interior formatting changes to match the cover, and the book sites are in some cases taking a while to process the changes, but by this time next week the splashy new cover should be visible everywhere. And I, for one, am very excited, because I absolutely love Nina and Ian’s new “look.” Hope my readers agree!

Published on May 27, 2016 06:00

May 20, 2016

Wine. Women, and Song

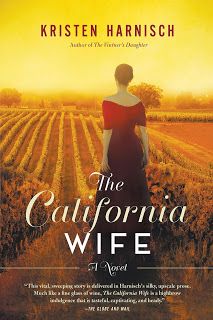

One of my favorite movies, as revealed in my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview with Kristen Harnisch, is Bottle Shock, the film starring Chris Pine and Alan Rickman. (In truth, I love anything starring Chris Pine or Alan Rickman, but that’s another story. RIP, Alan. You are missed.) Bottle Shock explores, with intelligence and humor, the moment in 1976 when the world woke up to the idea that not all great wine came from Europe.

One of my favorite movies, as revealed in my latest New Books in Historical Fiction interview with Kristen Harnisch, is Bottle Shock, the film starring Chris Pine and Alan Rickman. (In truth, I love anything starring Chris Pine or Alan Rickman, but that’s another story. RIP, Alan. You are missed.) Bottle Shock explores, with intelligence and humor, the moment in 1976 when the world woke up to the idea that not all great wine came from Europe.I remember, vaguely, when those results came in—and how surprising they were, but I was even more surprised to learn from The California Wife that in fact certain California vineyards were winning awards in Paris almost a century before that dramatic victory by North American reds and whites. I discovered quite a few more tidbits from our interview, but I won’t spoil them for you by revealing them here. Mostly I had a great conversation with a talented and articulate author. And we laughed a lot. Go listen to the interview (as always, it’s free), and you’ll find out why.

And by the way, kudos to whomever designed that gorgeous cover.

But here is a taste of the story, as always taken from New Books in Historical Fiction:

Sara Thibault and her new husband, Philippe Lemieux, grew up in Vouvray, amid the French vineyards that dot the Loire Valley. But when the phylloxera blight of the 1870s devastates their families’ business, Philippe decides to try his luck in California. Sara soon follows, driven by a tragic series of events detailed in The Vintner’s Daughter . The California Wife (She Writes Press, 2016), the stand-alone sequel to that earlier novel, traces the later history of Sara, Philippe, and the group of wholly or partially orphaned children whose care they undertake.

The California wine industry, although somewhat healthier than the French, has also suffered from the blight. Its reputation is less secure than that of its European rival, and the existence of too few outlets has driven prices down to the point where many vintners can hardly afford to harvest their crops. Meanwhile, Sara fears for the survival of the vines on her childhood estate, and Philippe worries about the cost of developing his current lands. Into this seething mix of competing loyalties steps, all unaware, Philippe’s former mistress, sharing a secret that he cannot hope to keep from the ears of his new bride.

Kristen Harnisch does a wonderful job of creating warm, believable characters who struggle for their future against catastrophe and crisis and the pull of their own pasts. If you have ever wondered who stands behind those labels at the local liquor store, this book will give you insight into their origins. Listen in as we explore winemaking now and then, including how, in the end, California put itself on the map as an essential part of the world’s viniculture.

Published on May 20, 2016 13:38