C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 37

February 24, 2017

Mother Love

One author who did not make the mistake of publishing too soon, as detailed in last week’s post, is Bren McClain, the author of One Good Mama Bone. As she puts it in my most recent interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, she is “a twenty-seven-year overnight success.” In the interview, she talks about her path to publication and the many, many rewrites it entailed, as well as the wonderful people who helped her along the way and the writing decisions she made, one of which involved imagining life from the perspective of a mama cow who still (thanks to her generosity, although she doesn’t put it quite that way) walks the earth at the advanced age of twenty-five.

One author who did not make the mistake of publishing too soon, as detailed in last week’s post, is Bren McClain, the author of One Good Mama Bone. As she puts it in my most recent interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, she is “a twenty-seven-year overnight success.” In the interview, she talks about her path to publication and the many, many rewrites it entailed, as well as the wonderful people who helped her along the way and the writing decisions she made, one of which involved imagining life from the perspective of a mama cow who still (thanks to her generosity, although she doesn’t put it quite that way) walks the earth at the advanced age of twenty-five.So stop by and listen to her insightful and often funny answers to my questions about her background, her books, her characters both charming and mean, and above all, how she came to write the COW! It’s free, it’s entertaining, it’s enlightening, and for sure you won’t regret spending fifty minutes with Bren. I know I enjoyed every minute of our conversation—and her book as well.

For more explanation as to why, see this post, repurposed from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Once in a while, a novel comes along that is just extraordinary, in the best sense of that word. Bren McClain’s One Good Mama Bone (Story River Books, 2017) falls into this category. In little more than 250 pages, McClain brings to life in spare but lyrical prose an unforgettable cast of characters struggling with poverty, family, and reputation against the backdrop of the early 1950s rural US South. Perhaps her most remarkable creation is Mama Red, a cow near the end of her “useful” life whose dedication to her calf becomes a symbol of mother love.

In the summer of 1944, Sarah Creamer helps her best friend deliver a child fathered by Sarah’s own husband. Out of fear and shame, her best friend kills herself shortly after the birth, leaving Sarah and her husband to raise the boy, whom they name Emerson Bridge. Over the next seven years Sarah’s husband drinks himself to death, at which point Sarah inherits a farm mortgaged to the hilt and a child she can’t afford to feed and fears that she doesn’t know how to love. Her sole talent is dressmaking, but times are tough throughout rural South Carolina and the bills continue to mount. When she comes across a newspaper article celebrating a local boy who earned $680 for his champion steer, she purchases a calf on credit from a local farmer and enters Emerson Bridge in the next year’s championship.

But the calf belongs to Mama Red, who breaks out of her corral and follows her baby to Sarah’s farm. Watching cow and calf activates the “mama bone” that Sarah’s own mother insisted Sarah did not have. Only then do she and Emerson Bridge discover what happens to the cattle when the championship ends. Love and respect clash with need, and Sarah and Emerson Bridge must decide whether the costs of success are too high.

Published on February 24, 2017 06:00

February 17, 2017

Publishing Too Soon

Writing is a tough business, especially novel writing. Almost by definition, it takes place in a virtual cave—one would-be author alone against the onslaught of the imagination. Characters talking in your head, moving pictures of setting and plot: isn’t this most people’s definition of insanity? Sure, the writer knows at some level that these are his or her creations, but tell that to a character who has decided that, come hell or high water, she is not embarking on that terribly convenient (for the author) mission that doesn’t happen to fit with her way of looking at the world.

Writing is a tough business, especially novel writing. Almost by definition, it takes place in a virtual cave—one would-be author alone against the onslaught of the imagination. Characters talking in your head, moving pictures of setting and plot: isn’t this most people’s definition of insanity? Sure, the writer knows at some level that these are his or her creations, but tell that to a character who has decided that, come hell or high water, she is not embarking on that terribly convenient (for the author) mission that doesn’t happen to fit with her way of looking at the world.In addition to the intense solitude of fiction writing as an exercise, budding novelists encounter another problem. To be able to write, you must first have learned to read. The vast majority of us learn to read at an early age, and those of us who become writers have often been reading for several decades before we produce finished work as adults. Since we are such accomplished and passionate readers, we tend to assume that we have what it takes as writers, and since we are writing alone, there is often no one to correct that misapprehension.

The third problem magnifies the first two: finishing a story feels fabulous. At the moment of typing “THE END,” almost every author knows this draft represents the greatest work in world literature, a piece of perfection equal to the classics. Every one of the nine hundred pages, now so laboriously completed, shines like the proverbial sun. It doesn’t matter whether it’s the first book or the twenty-first, in that instant of completion the thought of withholding this gift from its unwitting but eager readership seems cruel. And so the first draft gets pushed out into print before it’s ready.

In the olden days, by which I mean a decade ago, that last step was not possible. Vanity presses existed, but few people read the books they published. To reach a market, writers sent out typed, then e-mailed, queries to literary agents who, drat their uncaring souls, failed to recognize the genius. The agents did not reply or, if they did reply, sent standard responses. Writers had to work their way up to requests for full manuscripts, detailed critiques, and personalized rejection letters before they finally secured a contract. In the process, they did a lot of rewriting. And slowly, slowly, authors learned that, however necessary in terms of preparation and training, the mere fact of being avid readers did not mean that they had mastered the craft of novel writing.

Believe me, I know. I’ve been there and done that, as they say. Twenty-plus years ago, I sent queries to agents for novels that these days I can’t bear even to look at. I think of those queries and cringe. What must those agents have thought? But I know the answer: they had seen thousands of submissions just like mine, and within three pages, if not three paragraphs, they thought “here’s someone else who doesn’t know what she’s doing,” tossed my query aside, and sent the standard letter—or nothing.

At the time, I was disappointed, not to say devastated. But now I consider myself fortunate to have had that experience. It took me fifteen years to write a publishable novel, reading craft books and working with more accomplished fellow writers all the way, and in those fifteen years publishing changed. In many ways, it changed for the better, because a highly consolidated market rejected good books as well as those that still needed much more work. But in one respect, authors lost from the change. As I have discovered from hosting New Books in Historical Fiction and from co-founding Five Directions Press, it has become easy to publish a book too soon.

Not only beginners or self-published authors make this mistake. Even mature writers sometimes put out books at a point when they could use another round of editing or error checking, when the plot is still sketchy, when the main characters’ motivations remain cloudy or inconsistent and their developmental arcs unclear. In these cases, the writers are usually seeking to make money with additional titles or have signed a contract they must meet. Sometimes the writer has become such a big name that no one in publishing wants to criticize his/her books. But for whatever reason it happens, the person hurt in the end is the author. The established author at least has his or her early works for readers to enjoy. The new author may never recover from those slow beginnings, inept dialogue, clichéd emotions, and trite descriptions. At Five Directions Press, that’s one of the things we do for one another: we help one another decide when we can safely release our books.

So do yourself a favor. Put the first draft away, toast your achievement in champagne, and pat yourself on the back. You’ve earned every drop and chortle. You finished a novel, and that’s amazing. But don’t send the file out (or upload it for publication) just yet. Go back in a week—better, a month—take out the blue pencil, and revise. Read the dialogue aloud and listen to whether it sounds clunky. Show the manuscript to a writer friend you trust. Show it to a few more. Collect their comments and repeat. Get recommendations for books on writing and read them, or if you can, take a course. Hire an editor who specializes in your genre of fiction, who can point out where your specific story goes off the rails or needs further development. Join a critique group and learn while doing. Find a way that works for you. But whatever you do, don’t publish the first draft or even the third. One day, you’ll be glad you waited.

Image from Clipart.com, no. 20413568

Published on February 17, 2017 06:00

February 10, 2017

Welcome to Claudia Long

As a founding member of Five Directions Press, I was delighted to hear last week that Claudia H. Long had decided to join us. A San Francisco lawyer and, in her own words, “mother of two, wife, and cook,” Claudia is also a talented writer of historical fiction. Her first book,

Josefina’s Sin

, came out with Atria Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster, in 2011. Set in colonial Mexico at the end of the seventeenth century, it tells the story of a young wife whose path to maturity includes a love affair with a bishop that leaves her pregnant.

As a founding member of Five Directions Press, I was delighted to hear last week that Claudia H. Long had decided to join us. A San Francisco lawyer and, in her own words, “mother of two, wife, and cook,” Claudia is also a talented writer of historical fiction. Her first book,

Josefina’s Sin

, came out with Atria Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster, in 2011. Set in colonial Mexico at the end of the seventeenth century, it tells the story of a young wife whose path to maturity includes a love affair with a bishop that leaves her pregnant.The Harlot’s Pen , Claudia’s second novel, came out three years later. Its heroine, Violetta, works as a journalist in the tradition-breaking, steamy world of 1920s San Francisco. Extra steamy, in Violetta’s case: her book on working women takes her to a brothel frequented by some of the city’s most powerful men, and the federal agents set on suppressing the trade in vice (and keeping workers in their place) have no use for a Flapper with an attitude. Denise Steele selected it as her “Books We Loved” pick in May 2016.

But it’s The Duel for Consuelo and its impending sequel that brought Claudia to us. Consuelo also came out in 2014, with the now-defunct Booktrope Editions, and it needs a new home. Since our mission at Five Directions Press is to focus on “literary journeys less traveled,” a book set in early eighteenth-century Mexico is a perfect fit for us. So we look forward to republishing Consuelo and, by the end of this year, bringing out Claudia’s next Mexican novel. Currently titled “Chains of Silver,” this new book will be the third in the series that began with Josefina’s Sin. Where The Duel for Consuelo features Josefina’s son, now an adult, and introduces a young woman who must choose between love and her hidden Jewish faith, “Chains of Silver” extends this conflict to a new generation, in the person of a determined fourteen-year-old who must learn to balance the needs of self and family, including her religion.

The addition of Claudia as our eighth member means, among other things, that our cooperative is now about as large as it can get and continue to function effectively. We also have a lovely combination of writers with business, legal, marketing, media, developmental and line editing, artistic, and typesetting expertise. So despite the wisdom of “never say never,” we will not be looking to add anyone else for a while. But stop by our site to see what the eight of us have planned and to sign up for our newsletter (quarterly issues and book announcements only), and follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, and Instagram for quotations and images from our books as well as general news.

And don’t forget to like Claudia’s page on Facebook and follow her on Twitter. You can also check her website, linked above, to find out more about her and her books.

Welcome, Claudia! We can’t wait to start working on your books!

Published on February 10, 2017 06:00

February 3, 2017

The Roaring Twenties

As I mentioned in one of last year’s posts, “The Fog of War,” there seems to be a renewed interest in fictional exploration of the early twentieth century—perhaps because of the ongoing centennial of World War I. I had intended at the time to give a fuller treatment of one title I mentioned in that post, Beatriz Williams’

A Certain Age

, a book I absolutely loved, including a Q&A interview with the author. The interview never came off, but Williams has just published another book set in Jazz Age Manhattan,

The Wicked City

. She has a third, Cocoa Beach—still in the 1920s but set in Florida—due for release in July, at which point I am scheduled to interview her about all three for New Books in Historical Fiction.

As I mentioned in one of last year’s posts, “The Fog of War,” there seems to be a renewed interest in fictional exploration of the early twentieth century—perhaps because of the ongoing centennial of World War I. I had intended at the time to give a fuller treatment of one title I mentioned in that post, Beatriz Williams’

A Certain Age

, a book I absolutely loved, including a Q&A interview with the author. The interview never came off, but Williams has just published another book set in Jazz Age Manhattan,

The Wicked City

. She has a third, Cocoa Beach—still in the 1920s but set in Florida—due for release in July, at which point I am scheduled to interview her about all three for New Books in Historical Fiction.Part of the fun of Williams’ novels is discovering characters and settings that have cropped up before. The hero in A Certain Age, Captain Octavian Rofrano, also made an appearance in Fall of Poppies, an anthology of stories commemorating World War I that I featured in “Remembering the Great War.” The heroine’s youngest son, Billy Marshall, plays a role in The Wicked City, which opens in a Greenwich Village apartment building that once housed a speakeasy called the Christopher Club, also featured in A Certain Age. The modern-day heroine of The Wicked City lives in the same building—I think in the same apartment—once occupied by Geneva (Gin) Kelly, who anchors the 1924 portion of the book. And so it goes, in intertwining patterns.

So, what is The Wicked City about? In 1998, Ella leaves her husband after discovering he’s cheated on her. She takes refuge in a tiny apartment on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village, only to discover that her building is filled with tenants who defy the laws of New York apartment living by taking a strong interest in their fellow residents. Attempting to do laundry at the crack of dawn, she runs into Hector, who lives on the top floor and gives her a crash course in the apartment culture of 11 Christopher while she drinks him in with her eyes. He also warns her about the basement, with its ghostly noises and vibrating walls.

Naturally, Ella has to investigate, and we dive into the other half of the story. The noises and vibrations come from the speakeasy that occupied half the site in 1924. There Gin Kelly, who lives in the apartment next door, spends many an evening drinking and dancing with young Billy Marshall—Princeton man, heir to uptown wealth, and smitten. Until she runs into a revenue agent named Anson who wants her to help him bust up the illegal liquor business run by her stepfather, the very man Gin came to New York to escape.

The two stories take place side by side through a series of five acts: “We Meet,” “We Come to an Understanding,” etc. The writing sparkles, and the vocabulary, the descriptions, and even the reactions of the characters clearly differentiate past from present. More even than in A Certain Age, which combined a story set in 1922 with the solution to a mystery that took place a decade or so earlier, Williams adroitly balances developing romances with darker and more compelling plot lines, and her characters are appealing even when—perhaps especially when—they behave far from admirably. I can hardly wait for the next installment.

P. S. A Certain Age has one of the most gorgeous covers I’ve seen. Bravo to the designers!

Published on February 03, 2017 10:40

January 27, 2017

Bookshelf, January 2017

It’s been a while since I ran my last Bookshelf post, so with another lovely writing week taking up much of my time, this seems a good moment for one. Several of these books will eventually become the basis of podcast interviews at New Books in Historical Fiction (NBHF); others relate to the recently renamed (Mostly) Dead Writers’ Society (DWS) on GoodReads or to the developing catalogue at Five Directions Press. Most are by less well-known writers—some traditionally published, others not. Because isn’t that the fun part of reading: discovering a new writer, preferably one who has produced lots of books? So here we go, more or less in order.

Anchee Min,

Empress Orchid

(Mariner Books, 2005)

Anchee Min,

Empress Orchid

(Mariner Books, 2005)

Just finished this account of the early years that Cixi, the last empress of China, spent in the Forbidden City, between her selection as the fourth concubine of Emperor Xianfeng to his death and her ascension to the role of joint regent for their son. We watch her grow from a naive sixteen-year-old left to her own devices in the imperial palace to the emperor’s favorite companion and adviser to a capable woman who, even in her mid-twenties, defends her own and her son’s interests within a court that insists on underrating her intelligence and her talents. I read this as part of the DWS’s 2017 exploration of revolutions, starting with the Boxer Rebellion, and enjoyed it very much. The Boxer Rebellion doesn’t actually appear until the sequel, The Last Empress, but the earlier Taiping Rebellion forms part of the backdrop here. The same author's Becoming Madame Mao is also a favorite of mine.

Bren McClain, One Good Mama Bone (University of South Carolina Press, 2017)

Sarah Creamer, dirt-poor and widowed by an alcoholic who leaves her with a son he had with her best friend, struggles to pay the mortgage on her farm and raise a boy that’s not hers despite her own mother’s scornful comment: “You ain’t got one good mama bone in you, girl.” Salvation appears in the form of a young steer, destined to compete in a 1952 cattle show. But when Sarah discovers what may happen to her steer if he wins the prize, her developing instincts as a mother force her to reconsider where her true loyalties lie. My February interview for NBHF.

Beatriz Williams, The Wicked City (William Morrow, 2017)

A dual-time novel alternating between a modern-day New Yorker warned to stay out of a haunted basement in modern-day Greenwich Village and a flapper who loves to party in the same building in 1924, when it hosted one of the city’s most notorious speakeasies. By the author of A Certain Age, another Jazz Age story that I loved, this book was sent to me for an NBHF interview, but I was already booked; I plan to interview the author in July, when she will have another new novel, Cocoa Beach.

Lissa Evans, Their Finest (Harper Perennial, 2017)

This novel, originally published in the UK, has already become a major motion picture. Set in London in 1940, it follows the career of Catrin Cole, who works on propaganda films for the Ministry of Information and ends up producing a largely manufactured “true” story about two sisters at Dunkirk. In the current political climate, and especially as a specialist in Russian history, how could I resist? Another potential NBHF interview that I received too late to fit into my schedule.

Denise Allan Steele,

Rewind

(Five Directions Press, 2017)

Denise Allan Steele,

Rewind

(Five Directions Press, 2017)

A delightful, hilarious novel set in 1970s/80s Scotland and modern-day California. Karen Anderson at seventeen lives for ABBA, the Hustle, and the attentions of her school's bad boy, until he breaks her heart by taking up with the local tramp. Karen escapes to university, where she meets and falls in love with Jack, a cool guitar-playing student who hates Margaret Thatcher as much as she does. Thirty years later, married to Jack and living in California with two teenagers who barely give her the time of day, Karen falls into the middle-aged trap of wondering about the road not taken. Can you rewind the book of love, and if you can, should you? With a legion of Scots relatives to my name, I find this story irresistible. It’s like a journey home, with laughs.

Ronald E. Yates, Finding Billy Battles and The Improbable Journeys of Billy Battles (Xlibris, 2013 and 2016)

These first two books in a planned trilogy weave tales of the author’s family into a semi-fictional account of a nineteenth-century Kansan who travels the world, as rediscovered by his great-grandson a hundred years later. The author’s years of writing and teaching journalism give him an ear for dialogue, a knack for description, and an instinct for the telling anecdote that together make for sharp observations and a compelling style. The books read like a combination of travelogue and diary, with a good deal of history seamlessly tossed into the mix. My March NBHF interview.

Tiffany Reisz, The Night Mark (MIRA Books, 2017)

Another dual-time story, but this one involves time travel, like the Outlander series. Faye Barlow, reeling from the death of her beloved husband, takes a job photographing the South Carolina coast. Pulled toward the Bride Island lighthouse during one assignment, she keeps returning, drawn by the legend of a keeper’s daughter who drowned under mysterious circumstances in 1921. One night, a rogue wave drags Faye into the past, where she becomes caught up in a love story that is not her own. As a historian, I often fantasize about visiting the period I study, in reality or through fiction (as in The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel ), so I leaped at the chance to interview this author when her book comes out in April.

Michelle Cox, A Girl Like You and A Ring of Truth (She Writes Press, 2016 and 2017)

Two mystery novels set in 1930s Chicago, starring Henrietta Von Harmon and Inspector Clive Howard. Henrietta, despite her aristocratic-sounding name, has sole responsibility for her nasty mother and seven siblings since her father committed suicide after the great crash of 1929. She has just established herself in a job at a local dance hall when the floor matron turns up dead. When Inspector Cox recruits her help in solving the crime, love enters the picture. In book 2, buried family secrets threaten Henrietta’s and Clive’s prospects for happiness, even as another crime casts a shadow on their budding romance. What can I say? I love 1930s mystery stories of the Agatha Christie/Dorothy Sayers type, and these two books appear to be in that mode. My May NBHF interview, scheduled for right after the second book’s appearance in April.

Ariadne Apostolou, West End Quartet (Five Directions Press, 2017)

Four young women living in 1980s Manhattan join together to form an urban commune called Group, dedicated to feminist politics, anti-nuclear protests, and various other radical causes. When the Reagan years end, Mallory, Jasmina, Gwen, and Kleio travel along different paths, never quite losing contact but no longer close. Through separate novellas we trace crucial events in the lives of the first three (Kleio has her own book, Seeking Sophia, released in 2013), ending with their reunion in Greece just as Kleio is facing a big decision of her own. A richly realized and often poignant character study of four women who set out to change the world, only to discover that more often the world changes us.

That should keep me busy for a while. Check back every so often as the individual posts go up to find out more about what I thought of each individual book.

Anchee Min,

Empress Orchid

(Mariner Books, 2005)

Anchee Min,

Empress Orchid

(Mariner Books, 2005)Just finished this account of the early years that Cixi, the last empress of China, spent in the Forbidden City, between her selection as the fourth concubine of Emperor Xianfeng to his death and her ascension to the role of joint regent for their son. We watch her grow from a naive sixteen-year-old left to her own devices in the imperial palace to the emperor’s favorite companion and adviser to a capable woman who, even in her mid-twenties, defends her own and her son’s interests within a court that insists on underrating her intelligence and her talents. I read this as part of the DWS’s 2017 exploration of revolutions, starting with the Boxer Rebellion, and enjoyed it very much. The Boxer Rebellion doesn’t actually appear until the sequel, The Last Empress, but the earlier Taiping Rebellion forms part of the backdrop here. The same author's Becoming Madame Mao is also a favorite of mine.

Bren McClain, One Good Mama Bone (University of South Carolina Press, 2017)

Sarah Creamer, dirt-poor and widowed by an alcoholic who leaves her with a son he had with her best friend, struggles to pay the mortgage on her farm and raise a boy that’s not hers despite her own mother’s scornful comment: “You ain’t got one good mama bone in you, girl.” Salvation appears in the form of a young steer, destined to compete in a 1952 cattle show. But when Sarah discovers what may happen to her steer if he wins the prize, her developing instincts as a mother force her to reconsider where her true loyalties lie. My February interview for NBHF.

Beatriz Williams, The Wicked City (William Morrow, 2017)

A dual-time novel alternating between a modern-day New Yorker warned to stay out of a haunted basement in modern-day Greenwich Village and a flapper who loves to party in the same building in 1924, when it hosted one of the city’s most notorious speakeasies. By the author of A Certain Age, another Jazz Age story that I loved, this book was sent to me for an NBHF interview, but I was already booked; I plan to interview the author in July, when she will have another new novel, Cocoa Beach.

Lissa Evans, Their Finest (Harper Perennial, 2017)

This novel, originally published in the UK, has already become a major motion picture. Set in London in 1940, it follows the career of Catrin Cole, who works on propaganda films for the Ministry of Information and ends up producing a largely manufactured “true” story about two sisters at Dunkirk. In the current political climate, and especially as a specialist in Russian history, how could I resist? Another potential NBHF interview that I received too late to fit into my schedule.

Denise Allan Steele,

Rewind

(Five Directions Press, 2017)

Denise Allan Steele,

Rewind

(Five Directions Press, 2017)A delightful, hilarious novel set in 1970s/80s Scotland and modern-day California. Karen Anderson at seventeen lives for ABBA, the Hustle, and the attentions of her school's bad boy, until he breaks her heart by taking up with the local tramp. Karen escapes to university, where she meets and falls in love with Jack, a cool guitar-playing student who hates Margaret Thatcher as much as she does. Thirty years later, married to Jack and living in California with two teenagers who barely give her the time of day, Karen falls into the middle-aged trap of wondering about the road not taken. Can you rewind the book of love, and if you can, should you? With a legion of Scots relatives to my name, I find this story irresistible. It’s like a journey home, with laughs.

Ronald E. Yates, Finding Billy Battles and The Improbable Journeys of Billy Battles (Xlibris, 2013 and 2016)

These first two books in a planned trilogy weave tales of the author’s family into a semi-fictional account of a nineteenth-century Kansan who travels the world, as rediscovered by his great-grandson a hundred years later. The author’s years of writing and teaching journalism give him an ear for dialogue, a knack for description, and an instinct for the telling anecdote that together make for sharp observations and a compelling style. The books read like a combination of travelogue and diary, with a good deal of history seamlessly tossed into the mix. My March NBHF interview.

Tiffany Reisz, The Night Mark (MIRA Books, 2017)

Another dual-time story, but this one involves time travel, like the Outlander series. Faye Barlow, reeling from the death of her beloved husband, takes a job photographing the South Carolina coast. Pulled toward the Bride Island lighthouse during one assignment, she keeps returning, drawn by the legend of a keeper’s daughter who drowned under mysterious circumstances in 1921. One night, a rogue wave drags Faye into the past, where she becomes caught up in a love story that is not her own. As a historian, I often fantasize about visiting the period I study, in reality or through fiction (as in The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel ), so I leaped at the chance to interview this author when her book comes out in April.

Michelle Cox, A Girl Like You and A Ring of Truth (She Writes Press, 2016 and 2017)

Two mystery novels set in 1930s Chicago, starring Henrietta Von Harmon and Inspector Clive Howard. Henrietta, despite her aristocratic-sounding name, has sole responsibility for her nasty mother and seven siblings since her father committed suicide after the great crash of 1929. She has just established herself in a job at a local dance hall when the floor matron turns up dead. When Inspector Cox recruits her help in solving the crime, love enters the picture. In book 2, buried family secrets threaten Henrietta’s and Clive’s prospects for happiness, even as another crime casts a shadow on their budding romance. What can I say? I love 1930s mystery stories of the Agatha Christie/Dorothy Sayers type, and these two books appear to be in that mode. My May NBHF interview, scheduled for right after the second book’s appearance in April.

Ariadne Apostolou, West End Quartet (Five Directions Press, 2017)

Four young women living in 1980s Manhattan join together to form an urban commune called Group, dedicated to feminist politics, anti-nuclear protests, and various other radical causes. When the Reagan years end, Mallory, Jasmina, Gwen, and Kleio travel along different paths, never quite losing contact but no longer close. Through separate novellas we trace crucial events in the lives of the first three (Kleio has her own book, Seeking Sophia, released in 2013), ending with their reunion in Greece just as Kleio is facing a big decision of her own. A richly realized and often poignant character study of four women who set out to change the world, only to discover that more often the world changes us.

That should keep me busy for a while. Check back every so often as the individual posts go up to find out more about what I thought of each individual book.

Published on January 27, 2017 10:14

January 20, 2017

Writing All the Time

There’s an inverse ratio, I find, between working on a new draft of a novel and blogging. With the happy coincidence of Martin Luther King Day this Monday and my source of income being located in DC, where the university decided it was easier to close than deal with the insanity of requiring staff to navigate past inaugural events and protests, plus a relatively quiet week, I have focused every spare moment on The Vermilion Bird.

There’s an inverse ratio, I find, between working on a new draft of a novel and blogging. With the happy coincidence of Martin Luther King Day this Monday and my source of income being located in DC, where the university decided it was easier to close than deal with the insanity of requiring staff to navigate past inaugural events and protests, plus a relatively quiet week, I have focused every spare moment on The Vermilion Bird.The good news is that I have thirteen solid chapters, eight of which have already survived the scrutiny of my invaluable critique group. A fourteenth is slowly unrolling under my typing fingers; with luck, I can finish it and get a sketchy form of chapter 15 out of the way by Monday, when work again returns full force. If I hadn’t needed to research the layout, appearance, and lifestyle characteristic of the early sixteenth-century Kremlin (on which, see “Fortress City”), not to mention the position of Tatars within and immediately outside the city, I could have made even more progress, perhaps to two-thirds of a novel instead of one-half.

The “bad” news—although it’s not really that bad—is that I can concentrate on the dialogue and actions of my imaginary people or detour to write a blog post. So this week I decided to settle on a quick progress report and save the good stuff for next time.

Happy reading, and—if you write—happy writing. Rest assured that I will return just as soon as I stop, in the words of my standard auto-response message, “chasing phoenixes in sixteenth-century Moscow.” In the meantime, you may want to check out the monthly “Books We Loved” post at Five Directions Press. Because you can never have too many books to read …

And if you missed last week’s interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, give that a listen, too. Three million viewers tuned in for the first episode of the Masterpiece Theater miniseries Victoria, and here’s your chance to find out about the history behind the program as well as a bit about life behind the scenes. All loads of fun, and it’s free!

Image: Ivan Bilibin's illustration of Prince Ivan catching the firebird, in the public domain because it was published before 1923, via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on January 20, 2017 06:00

January 12, 2017

Queen of the World

It’s not news that the Internet has wrought dramatic changes in the way that the computer-connected world—which, we should keep in mind, is not the entire world—approaches many aspects of everyday life. Those of us old enough to remember typewriter ribbons and white-out, paper maps that tore along their folds, and clocks with hands rather than digital readouts have war stories to tell about those moments when we recognized that elements of life we took for granted had changed irrevocably. Mine was an evening drive through New Haven, looking for a famous pizza parlor with my son navigating from the back seat on his smart phone. I named the streets as we passed them, as I would to someone reading a map, and he said, with that voice only teenagers speaking to their “ancient” parents can truly master, “Mom, the phone knows where it is.” I remember thinking, “I don’t know where I am. What do you mean, the phone knows?” But of course, he was right.

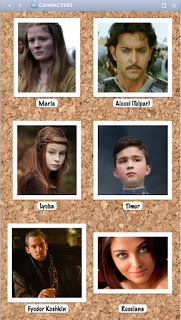

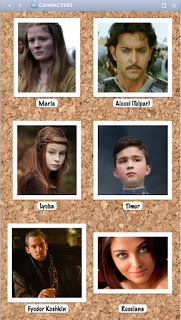

One such change—wrought by both the Internet and, before that, the cinema—is a renewed emphasis on visual representation. Text remains important, of course: people buy and read books, both print and digital; authors maintain blogs, like this one, and write materials of all sorts. But television, social media, YouTube videos, film, and other forms of still and moving images lie just a click away. Not every writer, by any means, imagines who would play which of his or her characters in a movie, but many do. I write in Storyist in part because it allows me to pin a cork board of images—film stars, random faces, portraits of sixteenth-century nobles and peasants as envisioned by nineteenth-century artists—on the right side of my screen as I write. Those faces inspire me, and when I find a new one that more closely resembles my evolving understanding of a particular person, I switch them out.

One such change—wrought by both the Internet and, before that, the cinema—is a renewed emphasis on visual representation. Text remains important, of course: people buy and read books, both print and digital; authors maintain blogs, like this one, and write materials of all sorts. But television, social media, YouTube videos, film, and other forms of still and moving images lie just a click away. Not every writer, by any means, imagines who would play which of his or her characters in a movie, but many do. I write in Storyist in part because it allows me to pin a cork board of images—film stars, random faces, portraits of sixteenth-century nobles and peasants as envisioned by nineteenth-century artists—on the right side of my screen as I write. Those faces inspire me, and when I find a new one that more closely resembles my evolving understanding of a particular person, I switch them out.

So I perfectly understand the impetus to televise fictional and historical stories. A good actor can convey with the flick of an eyebrow nuances of emotion that a novelist may need paragraphs to describe. Costumes, hairstyles, rooms, furniture, even mannerisms come across in a visual medium far more clearly than through a verbal exchange. Written works excel in taking the reader into a stranger’s mind, but for outward appearance and verisimilitude the screen has few equals.

The power of the image, though, makes accuracy essential. Costume designers routinely adjust historical styles to match current tastes, and that’s fine. But if a Carolingian lady is waltzing around in a crinoline, the audience gets the wrong impression, and that impression can be difficult to erase. The same holds true, to much greater degree, of time frames, personalities, and relationships.

That’s where the historical consultant comes in. In my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, talk with the historian Helen Rappaport about that important role, among other topics. The rest of this post, as usual, comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

That’s where the historical consultant comes in. In my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, talk with the historian Helen Rappaport about that important role, among other topics. The rest of this post, as usual, comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

The term “historical fiction” covers a wide range from what the mystery writer Josephine Tey once dubbed “history with conversation” to outright invention shading into fantasy. But behind every story set in the past lies the past itself, as re-created by scholars from the available evidence. This interview features Helen Rappaport, whose latest work reveals the historical background behind the Masterpiece Theater miniseries Victoria, due to air in the United States this month. Rappaport served as historical consultant to the show.

The Queen Victoria who gave her name to an age famous for a prudishness so extreme that even tables had limbs, not legs, is nowhere evident in Rappaport’s book, the television series, or the novel by Daisy Goodwin, also titled Victoria, that gave rise to the series. Victoria: The Heart and Mind of a Young Queen explores in vivid, compelling prose the letters, diaries, and other documents associated with the reign of a strong-minded, passionate, eager, inexperienced girl who took the throne just after her eighteenth birthday. This Victoria loved to ride, resisted marriage, fought to separate herself from her mother, detested her mother’s close adviser, and became infatuated with her prime minister and the future tsar of Russia before transferring her affections to Prince Albert, who initially did not impress her. Wildly devoted to her husband, she bore nine children but hated being pregnant and regarded newborn infants as ugly. Even her name caused controversy: christened Alexandrina, she switched to Victoria on taking the throne, overriding critics who insisted that Elizabeth or Charlotte were more suitable appellations for a British monarch. By the time she died sixty-three years later, entire generations understood the word “queen” as synonymous with “Victoria.”

Although the most powerful woman in the world, Victoria here makes some serious mistakes, as any eighteen-year-old thrust into the center of politics would. If she had no social media to record every misstep, she also had no publicity managers or image brokers to spin her rash remarks or misjudgments. As Daisy Goodwin notes in the foreword to this book, Victoria had to grow up in public, and she left a precious record of that journey in her own exquisite handwriting. But since this is the official companion volume to a television show, it also includes details about casting and costuming, as well as numerous photographs of the actors and background information about the times. It makes a perfect starting point for a discussion of history and historical fiction, their differences and similarities, and how to observe the requirements of one without violating the precepts of the other.

One such change—wrought by both the Internet and, before that, the cinema—is a renewed emphasis on visual representation. Text remains important, of course: people buy and read books, both print and digital; authors maintain blogs, like this one, and write materials of all sorts. But television, social media, YouTube videos, film, and other forms of still and moving images lie just a click away. Not every writer, by any means, imagines who would play which of his or her characters in a movie, but many do. I write in Storyist in part because it allows me to pin a cork board of images—film stars, random faces, portraits of sixteenth-century nobles and peasants as envisioned by nineteenth-century artists—on the right side of my screen as I write. Those faces inspire me, and when I find a new one that more closely resembles my evolving understanding of a particular person, I switch them out.

One such change—wrought by both the Internet and, before that, the cinema—is a renewed emphasis on visual representation. Text remains important, of course: people buy and read books, both print and digital; authors maintain blogs, like this one, and write materials of all sorts. But television, social media, YouTube videos, film, and other forms of still and moving images lie just a click away. Not every writer, by any means, imagines who would play which of his or her characters in a movie, but many do. I write in Storyist in part because it allows me to pin a cork board of images—film stars, random faces, portraits of sixteenth-century nobles and peasants as envisioned by nineteenth-century artists—on the right side of my screen as I write. Those faces inspire me, and when I find a new one that more closely resembles my evolving understanding of a particular person, I switch them out.So I perfectly understand the impetus to televise fictional and historical stories. A good actor can convey with the flick of an eyebrow nuances of emotion that a novelist may need paragraphs to describe. Costumes, hairstyles, rooms, furniture, even mannerisms come across in a visual medium far more clearly than through a verbal exchange. Written works excel in taking the reader into a stranger’s mind, but for outward appearance and verisimilitude the screen has few equals.

The power of the image, though, makes accuracy essential. Costume designers routinely adjust historical styles to match current tastes, and that’s fine. But if a Carolingian lady is waltzing around in a crinoline, the audience gets the wrong impression, and that impression can be difficult to erase. The same holds true, to much greater degree, of time frames, personalities, and relationships.

That’s where the historical consultant comes in. In my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, talk with the historian Helen Rappaport about that important role, among other topics. The rest of this post, as usual, comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

That’s where the historical consultant comes in. In my latest interview for New Books in Historical Fiction, talk with the historian Helen Rappaport about that important role, among other topics. The rest of this post, as usual, comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.The term “historical fiction” covers a wide range from what the mystery writer Josephine Tey once dubbed “history with conversation” to outright invention shading into fantasy. But behind every story set in the past lies the past itself, as re-created by scholars from the available evidence. This interview features Helen Rappaport, whose latest work reveals the historical background behind the Masterpiece Theater miniseries Victoria, due to air in the United States this month. Rappaport served as historical consultant to the show.

The Queen Victoria who gave her name to an age famous for a prudishness so extreme that even tables had limbs, not legs, is nowhere evident in Rappaport’s book, the television series, or the novel by Daisy Goodwin, also titled Victoria, that gave rise to the series. Victoria: The Heart and Mind of a Young Queen explores in vivid, compelling prose the letters, diaries, and other documents associated with the reign of a strong-minded, passionate, eager, inexperienced girl who took the throne just after her eighteenth birthday. This Victoria loved to ride, resisted marriage, fought to separate herself from her mother, detested her mother’s close adviser, and became infatuated with her prime minister and the future tsar of Russia before transferring her affections to Prince Albert, who initially did not impress her. Wildly devoted to her husband, she bore nine children but hated being pregnant and regarded newborn infants as ugly. Even her name caused controversy: christened Alexandrina, she switched to Victoria on taking the throne, overriding critics who insisted that Elizabeth or Charlotte were more suitable appellations for a British monarch. By the time she died sixty-three years later, entire generations understood the word “queen” as synonymous with “Victoria.”

Although the most powerful woman in the world, Victoria here makes some serious mistakes, as any eighteen-year-old thrust into the center of politics would. If she had no social media to record every misstep, she also had no publicity managers or image brokers to spin her rash remarks or misjudgments. As Daisy Goodwin notes in the foreword to this book, Victoria had to grow up in public, and she left a precious record of that journey in her own exquisite handwriting. But since this is the official companion volume to a television show, it also includes details about casting and costuming, as well as numerous photographs of the actors and background information about the times. It makes a perfect starting point for a discussion of history and historical fiction, their differences and similarities, and how to observe the requirements of one without violating the precepts of the other.

Published on January 12, 2017 12:14

January 6, 2017

Fortress City

It’s been a while since I wrote a history post, largely because I tend to do the most research either before I start a new project or when I hit a brick wall midway through the first draft and discover I actually have no idea what happened during X or what people did when faced with Y or, as in this case, what the Moscow Kremlin looked like in February 1537.

You might write off that last as a no-brainer, and I certainly would not blame you if you did. After all, Wikipedia can tell you that the current fortress walls have been on the same site since Pietro Solari directed their construction in 1485–1495. The best-known cathedrals and at least one palace date from the same period. So what’s the problem?

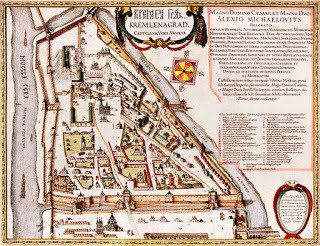

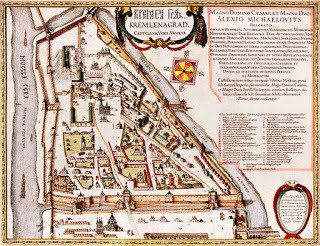

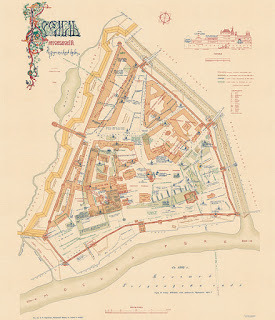

Well, in brief, there have been a few changes in the centuries since Ivan the Terrible was a child. Moreover, to quote Catherine Merridale in her invaluable Red Fortress: History and Illusion in the Kremlin: “The buildings also did not stand unaltered, and they could be the most treacherous witnesses of all. If a wall was repainted, or a palace knocked down and rebuilt, it was as if its previous incarnation had never been” (6). Although there are written records—and the occasional spectacular map, like this one copied in 1663 but originally drawn circa 1604—the actual environment has undergone five centuries of fire, destruction, rebuilding, and refurbishing. Many documents perished in those fires; many buildings were torn down or incorporated into larger structures, like the women’s quarters built by Alevisio of Milan, which now form the first floor of the larger Terem Palace built in 1635–1636. (A terem, in medieval Russia, refers to the part of a house or estate used to seclude women from contact with men outside the family, thus safeguarding their honor [read: chastity] and, not coincidentally, ensuring that girls did not form romantic attachments that could interfere with their fathers’ political plans.)

Nor are these the only types of alteration. The deep red of the walls, familiar from so many photographs, is achieved by paint. The underlying brick is much paler, closer to peach, and at times in the past has been covered in white stucco. The gingerbread towers of the modern Kremlin are seventeenth-century add-ons; the original towers were designed to menace from the far side of a moat that once separated the citadel from what is today called Red Square (then still devoid of St. Basil’s). You can see the moat at the bottom of Blaeu’s map, which should really be to the right, as Red Square lies to the east of the Savior Tower.

Nor are these the only types of alteration. The deep red of the walls, familiar from so many photographs, is achieved by paint. The underlying brick is much paler, closer to peach, and at times in the past has been covered in white stucco. The gingerbread towers of the modern Kremlin are seventeenth-century add-ons; the original towers were designed to menace from the far side of a moat that once separated the citadel from what is today called Red Square (then still devoid of St. Basil’s). You can see the moat at the bottom of Blaeu’s map, which should really be to the right, as Red Square lies to the east of the Savior Tower.

Even the purpose of the city has changed. At one time, the Kremlin was the city, an area about a quarter the size of today’s fortress protected by log palisades. By the 1530s, only the royal family and the most prestigious noble clans maintained living quarters inside the walls, which also hosted a monastery and a convent as well as the metropolitan of Moscow, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. Everyone else lived on the far side of today’s Red Square, in what became known (and is still known) as the Kitaigorod. In 1535, Grand Princess Elena of Russia, the mother of Ivan the Terrible and sometime heroine/sometime villain of my Legends series, ordered the construction of a second set of fortifications: a massive brick wall as thick as it was tall, so solid that it stood until Stalin went after it with dynamite four centuries later. Visitors to Moscow can still see its remnants today. The city expanded outward from there: two more sets of walls went up before the end of the seventeenth century, and the twenty-first-century city extends beyond those.

All this rebuilding and repainting makes life difficult for a novelist. What would my characters see when they enter the Kremlin? We can be reasonably certain that the bottom third of the Ivan the Great Bell Tower looked much the same then as now, although the iconic gilded cupola and the top two tiers did not appear until later. The Faceted Palace has survived, but the much larger collection of buildings where Ivan and his mother lived and governed has given way to the Terem Palace and the Great Kremlin Palace (built in 1837). The obviously eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century buildings can be eliminated, but what about the Tsaritsa’s Golden Chamber, which turns out to date from the 1550s (maybe) and has decorations matched to the 1590s, when Irina Godunova, sister to Boris Godunov and wife to Ivan the Terrible’s son Fyodor, ruled there? Was it part of an older structure that my characters might have encountered?

I checked the Russian chronicles to find out where Elena Glinskaya received the wives of Tatar khans and learned that the meetings took place “in the chambers near St. Lazarus’s.” But where was St. Lazarus’s? It’s not on any current map. It’s not on the 1604/63 map—except that it actually is, unmarked. According to “The Great Kremlin Palace in 1912,” the Church of St. Lazarus, built of wood in the fourteenth century, was “annexed to the south side of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin.” In 1479 the walls of both churches collapsed, and in 1514 Alevisio rebuilt a single church dedicated to the Virgin’s Nativity on the first floor, with the former Church of St. Lazarus underneath. Further renovations took place in the late seventeenth century, as a result of which the Church of St. Lazarus was forgotten until the construction of the Great Kremlin Palace uncovered its fourteenth-century shell. Today the church exists entirely within the Great Kremlin Palace, which is closed to visitors because the Russian president lives there. But before the revolution, the Church of the Virgin’s Nativity was the private chapel of the grand princesses and tsaritsas and—which is the most telling and delightful detail—it backed directly onto the residence set aside for the royal women, which eventually became the Terem Palace.

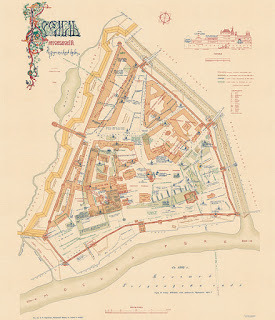

In this attempt to reconstruct the Kremlin as it might have appeared in 1537, in addition to the sources I’ve already mentioned, I stumbled on one more that has proved invaluable. In 1910, S. P. Bartenev—who in 1912 wrote the guidebook reproduced on “The Great Kremlin Palace” website—drew an overlay map of the Moscow Kremlin. The buildings that appeared in his day, many of which were destroyed in the Soviet period, are shown in orange. But there are layers and layers of overlapping buildings in green. These mark the locations of former noble estates, Dmitry Donskoi’s terem, Ivan the Terrible’s bedchamber, the palace assigned to Zoë Paleologa, and much, much more. The notations are handwritten in Russian, which is why it helps to speak the language, but the file on Wikimedia Commons, reproduced here in a small version, is huge. A desperate novelist can blow it up to read the tiny print. Combine its evidence with the paper-doll-like renditions of Blaeu’s 1663 map (he never saw the Kremlin, but the original artist obviously did, because the buildings match what few descriptions we have as well as the structures that remain), and one can at least begin to imagine what Maria may have seen as she traveled veiled in her enclosed sleigh to Grand Princess Elena’s reception hall.

So this is how I spent a good half of my vacation. Much of it went into writing, but a good deal involved peering at Bartenev’s map, comparing it with Blaeu’s, searching for old photographs and descriptions, and reading as much Kremlin history as I could absorb from modern historians and from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century accounts. It’s been fun, and I learned a lot. Not least that you can’t always tell a book by its cover—or a fortress by its walls.

Images: Joan Blaeu, Kremlenagrad map, 1663, in the public domain because of its age; Spasskaia tower, Kremlin, © Milan Nykodym, Czech Republic, CC BY-SA 2.0; overlay map from S. P. Bartenev, Moskovskii Kreml’ v starinu i teper’ (The Moscow Kremlin in Olden Times and Now [1910]), in the public domain because of its age—all via Wikimedia Commons.

You might write off that last as a no-brainer, and I certainly would not blame you if you did. After all, Wikipedia can tell you that the current fortress walls have been on the same site since Pietro Solari directed their construction in 1485–1495. The best-known cathedrals and at least one palace date from the same period. So what’s the problem?

Well, in brief, there have been a few changes in the centuries since Ivan the Terrible was a child. Moreover, to quote Catherine Merridale in her invaluable Red Fortress: History and Illusion in the Kremlin: “The buildings also did not stand unaltered, and they could be the most treacherous witnesses of all. If a wall was repainted, or a palace knocked down and rebuilt, it was as if its previous incarnation had never been” (6). Although there are written records—and the occasional spectacular map, like this one copied in 1663 but originally drawn circa 1604—the actual environment has undergone five centuries of fire, destruction, rebuilding, and refurbishing. Many documents perished in those fires; many buildings were torn down or incorporated into larger structures, like the women’s quarters built by Alevisio of Milan, which now form the first floor of the larger Terem Palace built in 1635–1636. (A terem, in medieval Russia, refers to the part of a house or estate used to seclude women from contact with men outside the family, thus safeguarding their honor [read: chastity] and, not coincidentally, ensuring that girls did not form romantic attachments that could interfere with their fathers’ political plans.)

Nor are these the only types of alteration. The deep red of the walls, familiar from so many photographs, is achieved by paint. The underlying brick is much paler, closer to peach, and at times in the past has been covered in white stucco. The gingerbread towers of the modern Kremlin are seventeenth-century add-ons; the original towers were designed to menace from the far side of a moat that once separated the citadel from what is today called Red Square (then still devoid of St. Basil’s). You can see the moat at the bottom of Blaeu’s map, which should really be to the right, as Red Square lies to the east of the Savior Tower.

Nor are these the only types of alteration. The deep red of the walls, familiar from so many photographs, is achieved by paint. The underlying brick is much paler, closer to peach, and at times in the past has been covered in white stucco. The gingerbread towers of the modern Kremlin are seventeenth-century add-ons; the original towers were designed to menace from the far side of a moat that once separated the citadel from what is today called Red Square (then still devoid of St. Basil’s). You can see the moat at the bottom of Blaeu’s map, which should really be to the right, as Red Square lies to the east of the Savior Tower.Even the purpose of the city has changed. At one time, the Kremlin was the city, an area about a quarter the size of today’s fortress protected by log palisades. By the 1530s, only the royal family and the most prestigious noble clans maintained living quarters inside the walls, which also hosted a monastery and a convent as well as the metropolitan of Moscow, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church. Everyone else lived on the far side of today’s Red Square, in what became known (and is still known) as the Kitaigorod. In 1535, Grand Princess Elena of Russia, the mother of Ivan the Terrible and sometime heroine/sometime villain of my Legends series, ordered the construction of a second set of fortifications: a massive brick wall as thick as it was tall, so solid that it stood until Stalin went after it with dynamite four centuries later. Visitors to Moscow can still see its remnants today. The city expanded outward from there: two more sets of walls went up before the end of the seventeenth century, and the twenty-first-century city extends beyond those.

All this rebuilding and repainting makes life difficult for a novelist. What would my characters see when they enter the Kremlin? We can be reasonably certain that the bottom third of the Ivan the Great Bell Tower looked much the same then as now, although the iconic gilded cupola and the top two tiers did not appear until later. The Faceted Palace has survived, but the much larger collection of buildings where Ivan and his mother lived and governed has given way to the Terem Palace and the Great Kremlin Palace (built in 1837). The obviously eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century buildings can be eliminated, but what about the Tsaritsa’s Golden Chamber, which turns out to date from the 1550s (maybe) and has decorations matched to the 1590s, when Irina Godunova, sister to Boris Godunov and wife to Ivan the Terrible’s son Fyodor, ruled there? Was it part of an older structure that my characters might have encountered?

I checked the Russian chronicles to find out where Elena Glinskaya received the wives of Tatar khans and learned that the meetings took place “in the chambers near St. Lazarus’s.” But where was St. Lazarus’s? It’s not on any current map. It’s not on the 1604/63 map—except that it actually is, unmarked. According to “The Great Kremlin Palace in 1912,” the Church of St. Lazarus, built of wood in the fourteenth century, was “annexed to the south side of the Church of the Nativity of the Virgin.” In 1479 the walls of both churches collapsed, and in 1514 Alevisio rebuilt a single church dedicated to the Virgin’s Nativity on the first floor, with the former Church of St. Lazarus underneath. Further renovations took place in the late seventeenth century, as a result of which the Church of St. Lazarus was forgotten until the construction of the Great Kremlin Palace uncovered its fourteenth-century shell. Today the church exists entirely within the Great Kremlin Palace, which is closed to visitors because the Russian president lives there. But before the revolution, the Church of the Virgin’s Nativity was the private chapel of the grand princesses and tsaritsas and—which is the most telling and delightful detail—it backed directly onto the residence set aside for the royal women, which eventually became the Terem Palace.

In this attempt to reconstruct the Kremlin as it might have appeared in 1537, in addition to the sources I’ve already mentioned, I stumbled on one more that has proved invaluable. In 1910, S. P. Bartenev—who in 1912 wrote the guidebook reproduced on “The Great Kremlin Palace” website—drew an overlay map of the Moscow Kremlin. The buildings that appeared in his day, many of which were destroyed in the Soviet period, are shown in orange. But there are layers and layers of overlapping buildings in green. These mark the locations of former noble estates, Dmitry Donskoi’s terem, Ivan the Terrible’s bedchamber, the palace assigned to Zoë Paleologa, and much, much more. The notations are handwritten in Russian, which is why it helps to speak the language, but the file on Wikimedia Commons, reproduced here in a small version, is huge. A desperate novelist can blow it up to read the tiny print. Combine its evidence with the paper-doll-like renditions of Blaeu’s 1663 map (he never saw the Kremlin, but the original artist obviously did, because the buildings match what few descriptions we have as well as the structures that remain), and one can at least begin to imagine what Maria may have seen as she traveled veiled in her enclosed sleigh to Grand Princess Elena’s reception hall.

So this is how I spent a good half of my vacation. Much of it went into writing, but a good deal involved peering at Bartenev’s map, comparing it with Blaeu’s, searching for old photographs and descriptions, and reading as much Kremlin history as I could absorb from modern historians and from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century accounts. It’s been fun, and I learned a lot. Not least that you can’t always tell a book by its cover—or a fortress by its walls.

Images: Joan Blaeu, Kremlenagrad map, 1663, in the public domain because of its age; Spasskaia tower, Kremlin, © Milan Nykodym, Czech Republic, CC BY-SA 2.0; overlay map from S. P. Bartenev, Moskovskii Kreml’ v starinu i teper’ (The Moscow Kremlin in Olden Times and Now [1910]), in the public domain because of its age—all via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on January 06, 2017 06:00

December 30, 2016

Moving on to 2017

Incredibly—or so it seems—2016 is about to head for the hills of history. And what a year it was, full of surprises big and small. So, as has become my habit on this blog, I will use this last post of the year to check in on how things went and set some new goals for next year. The list for 2016 included:

Incredibly—or so it seems—2016 is about to head for the hills of history. And what a year it was, full of surprises big and small. So, as has become my habit on this blog, I will use this last post of the year to check in on how things went and set some new goals for next year. The list for 2016 included:(1) finishing the final draft of The Swan Princess and seeing it in print and e-book formats;

(2) making significant progress on The Vermilion Bird, preferably to the point of a full rough draft (even if it’s very rough);

(3) chairing a roundtable on the uses of historical fiction in the classroom, scheduled for November 2016 but not yet approved by the sponsoring organization;

(4) upping the number of my New Books in Historical Fiction interviews to one every three weeks, yielding eighteen for the year;

(5) maintaining my website and the Five Directions Press website—which means expanding the number of authors and titles available, filling out the More Books Worth Reading page, and keeping the news & events page up to date;

(6) posting to this blog every Friday;

(7) maintaining and strengthening my relationships with fellow writers;

(8) continuing to improve my grasp of marketing, on both my own behalf and that of Five Directions Press; and

(9) completing three GoodReads challenges.

I actually managed to fulfill most of these goals. My NBHF interviews topped out at seventeen rather than eighteen, and the first draft of The Vermilion Bird is still only about halfway done—largely because the project has demanded more research than I expected (I am currently reading up on the complicated history of the Moscow Kremlin, for example, thanks to Catherine Merridale’s Red Fortress) but also because of a delightful development that I did not anticipate at this time last year: Five Directions Press has doubled in size, with six active authors and three associates.

As a result, we put out four books last year, with five to six planned for next year. Five Directions Press also added a monthly feature called “Books We Loved,” in which we recommend those titles we especially enjoyed: small-press, self-published, traditionally published fiction and nonfiction. The list goes up around the middle of each month. You can find it at http://www.fivedirectionspress.com/newsletter or by liking us on Facebook. (You can also follow us on Twitter.) While there, don’t forget to sign up for our quarterly newsletter. We send messages only for new releases and the newsletter itself, and we never sell addresses. It’s the best way to stay informed about what we’re doing and to learn about us and other authors through our regular interviews. You also get access to free coloring pages based on our books and a chance to win our annual Christmas basket.

Which brings me to next year’s goals. I decided not to take on more reading challenges next year, because between research and my own books and interview preparation and 5DP authors and “Books We Loved,” not to mention the occasional library book group session, I barely have time to breathe. I’m also forced to cut back on the interviews again: every three weeks proved really hard to sustain. That leaves the following writing/reading goals for 2017:

(1) completing The Vermilion Bird and seeing it in print;

(2) starting The Shattered Drum, the last of my Legends of the Five Directions although I also plan a spinoff series set in Russia around the same time;

(3) conducting twelve New Books in Historical Fiction interviews;

(4) typesetting/proofing, producing e-books, and in some cases editing the Five Directions Press titles scheduled for next year—Rewind, West End Quartet, The Falcon Strikes, The Vermilion Bird, and A Holiday Gift, more or less in that order;

(5) maintaining my website and the Five Directions Press website—which means keeping track of the “Books We Loved” posts, expanding the number of authors and titles available, and keeping the news & events page up to date;

(6) posting to this blog every Friday;

(7) maintaining and strengthening my relationships with fellow writers; and

(8) continuing to improve my grasp of marketing, on both my own behalf and that of Five Directions Press—including finding more ways to get reviews.

Let’s see how I do. Meantime, Happy New Year, everyone!

P.S. Cat #3 is on his way home. In the end, it was a very successful visit, and Cat #1 hasn't had that much exercise in years. In fact, he is sleeping it off as I write....

Images: “Happy New Year 2017” Clipart no. 109785399, Sleepy Siamese © 2016 C. P. Lesley

Published on December 30, 2016 06:00

December 23, 2016

Cat Wars

I’d planned to produce a writing post this week—or perhaps a history post—since I am off work and madly tearing through The Vermilion Bird. But the end of the week rolled around, and I decided history and writing craft were just too serious to use as topics this close to the holidays. So instead, I have a post about cats—because everyone knows the Internet loves cats, right?

It all began when the Filial Unit and his girlfriend decided to visit us for the holidays. As a mom, I’m genetically programmed to welcome such visits with unbounded joy. And when they floated the idea that their cat, a rescue animal who has lived with them for only a couple of months, might not do well with strangers coming in to feed him, the Mom program kicked in and I offered to host the cat, too—even though Sir Percy and I have two cats of our own.

Now, the new cat is a fine animal. He endured seven hours in the cat carrier with minimal fussing. He broke free of the confinement room and was exploring within hours. He’s coping well with new territory and new people, with just the occasional hiss or growl to let us know he hasn’t completely accepted us yet, but he’ll tolerate us so long as we give him some space. And the title of my post is somewhat misleading, in the sense that very little fur has actually flown so far. Even so, the acclimatization has been fun to watch. And not to get too heavy, it might even say something about conflicts and their resolution—and not only among cats.

First, the newcomer. Let’s call him Cat #3. After living who knows where, then in a shelter, then in a small apartment with two people, he’s naturally a bit nervous at a sudden transition to a full-sized house with four people and two other cats. He knows the basic cat drill: hiss a warning, growl if needed, hit out as a last resort, slink away if possible. But he has trouble figuring out when to yield and, especially, how to tell if Person or Cat X actually poses a threat.

Enter Cat #2, the only female in the group. She’s also a rescue cat, a feral kitten captured at six months, so she went from the outside world to a informal shelter with few cages but many cats to our quiet house with two adults who are around almost all the time. She has no desire to live anywhere else and a hyper-vigilant threat center that even eight years of daily reassurance can’t entirely reset. One hiss from the newcomer, and she raced for her favorite hidey hole. She stayed there for thirty-six hours until I dug her out and put her in a quiet room by herself, with food and water and a litter box. Since then, she’s reclaimed her spot in my study, but she’s still not sure about Cat #3 (who as I write this is inching his way up the stairs, one by one).

Enter Cat #2, the only female in the group. She’s also a rescue cat, a feral kitten captured at six months, so she went from the outside world to a informal shelter with few cages but many cats to our quiet house with two adults who are around almost all the time. She has no desire to live anywhere else and a hyper-vigilant threat center that even eight years of daily reassurance can’t entirely reset. One hiss from the newcomer, and she raced for her favorite hidey hole. She stayed there for thirty-six hours until I dug her out and put her in a quiet room by herself, with food and water and a litter box. Since then, she’s reclaimed her spot in my study, but she’s still not sure about Cat #3 (who as I write this is inching his way up the stairs, one by one).

But the surprise hero of this narrative is Cat #1, our senior citizen. Cat #1 lives by Siamese (Cat) rules, of which the most fundamental is “Thou shalt snuggle.” He’s already suffered a certain amount of disappointment due to Cat #2’s propensity to flee at the very moments when, in his mind, snuggling is required. But diligent work on his part has won her over, most of the time. Indeed, just before the arrival of Cat #3, Cats 1 and 2 spent the entire evening huddled together on the couch, sharing an appropriately named Snugli. Still, there was some question as to how he might react to the arrival of an unfamiliar, younger tomcat.

It’s been an education for all concerned. Cat #1’s first reaction was to walk into the bedroom assigned to Cat #3 and his family—in the middle of the night, no less—and, ignoring all hissing and growling, to establish his right to the bed, after which he sauntered off to eat what remained of Cat #3’s dinner. Message: “My house, my rules. Get used to it.”

The next day, he followed Cat #3 around the house, stopping just close enough to elicit the first rumbling growl, then sitting there until it stopped before edging in closer. He did not look at Cat #3 while doing this, because staring is an aggressive act between cats. But he didn’t back down, either. After a couple of hours, Cat #3 gave up on the hissing and growling, at least with the other cats. He also became more accepting of the unknown humans, although he’s having none of that petting. That’s right out.

By the third day, Cats 1 and 2 are hanging out together as they always have, and Cat #3 has taken to roaming the house, often in the vicinity of the resident cats but not close enough either to cause trouble or to consider them friends. Cat #1 has socialized the newcomer with not much more than a sideways stare.

In all this back-and-forth, the cats have come to blows exactly once. Cat #3, preoccupied with the raising of the Christmas tree, did something that attracted the ire of Cat #1, who despite his fifteen years and kidney problems, let out an ear-splitting yowl and chased Cat #3 back to his borrowed room. Fifteen minutes later, tops, Cat #3 was back, his past sins forgiven.

Is that the end of the story? Unclear, as they still have a good week of reorienting to go. And the relationship between us and Cat #3, while developing, has grown much more slowly. We don’t read the signals as well, and we certainly don’t send them as clearly. Conflict avoidance demands effective communication, and communication, first and foremost, requires us to speak the same language. Guess I’d better go and brush up on my Cat.

Still, they are an example to the rest of us in this conflict-ridden world. So in the spirit of the season, peace and good will to all. Happy holidays, everyone, and best wishes for a stellar year to come!

Images: Wreath Clipart. no. 7597540; Cats 1–3 © 2016 C. P. Lesley.

Images: Wreath Clipart. no. 7597540; Cats 1–3 © 2016 C. P. Lesley.

It all began when the Filial Unit and his girlfriend decided to visit us for the holidays. As a mom, I’m genetically programmed to welcome such visits with unbounded joy. And when they floated the idea that their cat, a rescue animal who has lived with them for only a couple of months, might not do well with strangers coming in to feed him, the Mom program kicked in and I offered to host the cat, too—even though Sir Percy and I have two cats of our own.

Now, the new cat is a fine animal. He endured seven hours in the cat carrier with minimal fussing. He broke free of the confinement room and was exploring within hours. He’s coping well with new territory and new people, with just the occasional hiss or growl to let us know he hasn’t completely accepted us yet, but he’ll tolerate us so long as we give him some space. And the title of my post is somewhat misleading, in the sense that very little fur has actually flown so far. Even so, the acclimatization has been fun to watch. And not to get too heavy, it might even say something about conflicts and their resolution—and not only among cats.

First, the newcomer. Let’s call him Cat #3. After living who knows where, then in a shelter, then in a small apartment with two people, he’s naturally a bit nervous at a sudden transition to a full-sized house with four people and two other cats. He knows the basic cat drill: hiss a warning, growl if needed, hit out as a last resort, slink away if possible. But he has trouble figuring out when to yield and, especially, how to tell if Person or Cat X actually poses a threat.

Enter Cat #2, the only female in the group. She’s also a rescue cat, a feral kitten captured at six months, so she went from the outside world to a informal shelter with few cages but many cats to our quiet house with two adults who are around almost all the time. She has no desire to live anywhere else and a hyper-vigilant threat center that even eight years of daily reassurance can’t entirely reset. One hiss from the newcomer, and she raced for her favorite hidey hole. She stayed there for thirty-six hours until I dug her out and put her in a quiet room by herself, with food and water and a litter box. Since then, she’s reclaimed her spot in my study, but she’s still not sure about Cat #3 (who as I write this is inching his way up the stairs, one by one).