C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 36

July 7, 2017

Writers' Intuition

In last week’s discussion of themes I mentioned the idea, ruthlessly cribbed from John Truby’s

The Anatomy of Story

, that characters in a novel do not exist in isolation. Instead they form a web, and their interactions through the plot push the story forward, cause the protagonists to change, and embody varying approaches to the novel’s central moral argument, its theme.

In last week’s discussion of themes I mentioned the idea, ruthlessly cribbed from John Truby’s

The Anatomy of Story

, that characters in a novel do not exist in isolation. Instead they form a web, and their interactions through the plot push the story forward, cause the protagonists to change, and embody varying approaches to the novel’s central moral argument, its theme.I also noted that at least in my case, themes arise from my subconscious mind. I discover them only after I complete the first draft (other people’s mileage no doubt varies, as the saying goes). Although I plan novels in various ways discussed elsewhere on this blog, my best writing appears when I fall into the zone where words pour onto the page and I become more a recorder than a planner. In the zone I write by instinct. Sometimes the results are kasha, but more often they have a flow that I can’t attain otherwise. Almost always they reveal elements of a character I hadn’t previously recognized. And those elements can surprise me.

Take, for example, Tulpar, an antagonist in The Winged Horse. When I set up that novel, I knew I wanted to explore the consequences of polygamy on the children, especially the sons, of men with multiple wives. Even judged by the standards of the Russian court in the 1530s, which forms the backdrop of the Legends novels and where the royal family could give the Borgias a run for their money, the Tatar successor states to the Mongol Empire had an extraordinarily large number of khans who came to power by assassinating their brothers.

In part, it was an example of “rule by the strongest”—carried to its extreme in the Ottoman Empire, where a system developed in which each concubine could have no more than one son and each sultan began his reign by tracking down and killing his half-brothers. But the reality that so many of the sons had different mothers must, I think, have also played a role in the conflict. Full brothers can, of course, hate each other and try to kill each other. And the half-brothers often fought together as well as against one another. Even so, I was curious about what role polygamy might play.

I decided to give Ogodai a half-brother, Tulpar, older than he and therefore stronger and more experienced, since an antagonist’s main role in a novel is to oppose the protagonist and thus force the protagonist to change. Most of us resist change, so the more powerful the antagonist, the greater the pressure on the hero/heroine to buckle down and do the hard work of self-improvement. Even in a romance, the hero and heroine typically act as antagonists for each other, at the same time as they are both protagonists. That’s why love stories so often start out with a man and woman who either dislike each other or see a situation in opposite ways. Without that conflict, the characters have no reason to change. There is no story.

So far, so good. But right away I ran into a problem: I hadn’t ever mentioned this older half-brother in The Golden Lynx. Well, how could I when I hadn’t created him yet? So I came up with a story for why no one in the family talked about him, and although I knew it was a bit far-fetched, it worked well enough for that book. The idea was for the two half-brothers to battle it out to the end, and may the best man win. They had plenty to fight over: a potential wife, leadership, bragging rights, a sexy concubine, even a philosophy of how this independent horde could preserve its freedom. The main difference between the brothers was character.

Then something happened. I realized that Tulpar was a perfect match for someone else in the series. How did I know? At the time, I couldn’t have said. I just thought, “Oh, those two so deserve each other. It would be great fun to throw them together and see what happens.” But looking back, I see that somehow I grasped that they were dealing with the same problem, but starting from very different places and approaching their troubles in very different ways. Their assumptions and reactions would push them to change, then support them as they changed. Even then, it took a third character to intervene and show me (and them) how the change could come about. A character who knew the hidden story and could act as an intermediary—and no, I won’t tell you more than that. You have to read the book to find out!

Getting from Point A to Point B took a lot of work. I had to twist things around so the new story could emerge from the old one. I had to go back to the far-fetched explanation and completely rework it so that it would make sense from the perspective of this character who had revealed his hidden depths in that unexpected way. I had to figure out how that realization altered what I could demand of him. Most important, I needed to understand how Tulpar’s view of the world would interact with that of the other characters. Where was the web? Who else in the series shared these issues, and how would they contribute to the whole? But the effort was worth it, every bit, because it made for a better story. And in the process I fell in love with them, as I do with all my main characters; otherwise I can’t write them.

It took me most of the first draft of The Vermilion Bird to answer the questions. And wouldn’t you know? Halfway through another character decided to share her story. I never did find a way to work it into this novel, and I am not certain this particular character would ever undertake the difficult work of personal growth. So I have yet to decide what to do with this information. Perhaps she will always lurk in the background, an amusing distraction, a perennial secondary figure.

But I’m laying the groundwork, just in case. Because I wouldn’t put it past her to take over a novel of her own. Call it writers’ intuition. It’s happened before.

Image: Clipart no. 314581

Published on July 07, 2017 06:00

June 30, 2017

The Story Behind the Story

Last week I mentioned in passing Nancy Kress’s

Dynamic Characters

. Toward the end of that book, she has a chapter on theme, which she renames “worldview” to avoid the cringe that most of us experience in recalling elementary- through high-school literature classes and all the themes we had not then lived long enough to recognize, never mind understand.

Last week I mentioned in passing Nancy Kress’s

Dynamic Characters

. Toward the end of that book, she has a chapter on theme, which she renames “worldview” to avoid the cringe that most of us experience in recalling elementary- through high-school literature classes and all the themes we had not then lived long enough to recognize, never mind understand. The chapter got me thinking: how would I, as an adult, define theme in reference to a novel? Does a novel even need a theme? Many writers insist that their works neither have nor require a theme, and that it’s up to readers to decide what meaning a book has for them. Others, including myself, disagree. A theme, as I show below, acts as a kind of organizing principle, imparting emotional coherence to a work of fiction. It keeps plot and character focused on the essentials.

Now I would be the first to admit that I pay little attention to theme in the initial stages of writing. First off, only some stories present themselves to me in sufficient detail early on for me to perceive the underlying theme. Even the few that do I don’t entirely trust: they are likely to morph midway through, revealing a theme I had not anticipated. But once that first draft is done, I agree with Kress that a theme helps pull a story together. As John Truby notes in The Anatomy of Story —another on my top five list of must-have writing craft books—it’s a mistake to regard characters as existing in isolation. Instead they embody differing attitudes and responses to the novel’s central theme. The plot offers them a chance to express and develop those responses.

So what is a theme? Is it really the same as a worldview? Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary defines it as “a subject or topic of discourse or artistic representation,” which doesn’t clarify much. Truby equates it with the writer’s moral vision, which does correspond with a worldview in part yet seems to offer a more exact definition. But I think the concept is much simpler than that. In brief, the theme is what the book is really about.

Take my Legends novels as examples. The theme in The Golden Lynx is vengeance: what do you do when someone close to you, an innocent, is murdered? One approach adopted by the characters leads them to kill in return, out of a desire for revenge or justice. A second has them take refuge in religion. A third pushes them to investigate what went wrong, including whether the innocent was in fact as guiltless as the family believed. A fourth redefines vengeance as preventing a different crime, and so on. The varying fates of those embracing this or that approach express my moral vision about revenge and what it can and cannot do for people.

In The Winged Horse, the story—the theme—revolves around the competing claims of loyalty: to oneself, to others, to a principle or a cause. The Swan Princess explores integrity, in this case from the perspective of a young woman who has gone too far in the direction of pleasing others and needs to recover, then incorporate, her own sense of herself without swinging from one extreme to the other. The Vermilion Bird, almost finished but not yet published, focuses on family through a group of characters who in some cases adore their families (who may not always deserve their love) and in others can barely bring themselves to speak to their family members (who do not necessarily deserve their dislike, although they have certainly done things to provoke it). Book 5, The Shattered Drum, is one of the rare novels to have already revealed its basic structure—probably because it ends the series, meaning it has a lot of loose ends to tie up. But I am less than twenty pages into it, so while I have a hint of what the theme may be, I know better than to reveal it yet.

You have no doubt noticed that these themes are interconnected. The desire for vengeance arises in part from loyalty to the person hurt, which in turn often comes from that person being a close friend or family member. Loyalty can inhibit the development of a separate identity and thus of integrity, which is above all the decision to respect and value one’s private self. Families certainly impose demands and expectations on their members, behaving and expressing emotions in ways specific to the culture in which they live but also to themselves. These demands necessarily fit some personalities better than others, and that in turn feeds questions of identity and integrity: How does a person like Maria, heroine of The Vermilion Bird, cope inside a structure that ruthlessly suppresses her gifts and imposes tasks on her in which she has no interest? How does she respond when a different family makes different assumptions that, however welcome, force her to change her fundamental beliefs about who she can and should become?

The Shattered Drum, too, incorporates elements of these themes. Which one dominates in the end will have more to do with emphasis than exclusivity. As writers we constantly revisit our own story, from different angles and with varying perspectives. The appeal to readers depends on the extent to which our problems reflect their own—or, more grandly, basic human themes.

Put that way, the concept of theme seems not so difficult to grasp. When we sit down to write a book, especially a novel, we may not have a particular theme in mind. Perhaps it’s even better not to have one. Then we can give our imagination free rein in the beginning rather than force it into a box. But for sure, our subconscious minds have a theme, and by the end of the first draft it will become obvious. At that point, the writer’s job becomes exploring the theme from as many angles and viewpoints as possible. Because if you have nothing to say, why write a book in the first place?

Image: Clipart no. 109572471.

Published on June 30, 2017 06:00

June 23, 2017

The Beast Within

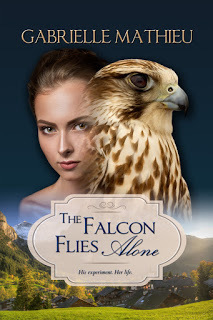

Early in my interview with Gabrielle Mathieu for New Books in Historical Fiction, I ask her about the tag line for the first book in her Falcon trilogy, The Falcon Flies Alone: “We all have a beast locked within us, but in Peppa’s case it’s more than a figure of speech.” We talked about anger and self-assertion, especially in women, and how they are often socially suppressed or, if not suppressed, evaluated differently from the same behavior in men. Gabrielle notes that she is not as blunt in her anger as her heroine, Peppa, but instead tends to avoid conflict. I could relate, as I have the same issue with several of my heroines.

Early in my interview with Gabrielle Mathieu for New Books in Historical Fiction, I ask her about the tag line for the first book in her Falcon trilogy, The Falcon Flies Alone: “We all have a beast locked within us, but in Peppa’s case it’s more than a figure of speech.” We talked about anger and self-assertion, especially in women, and how they are often socially suppressed or, if not suppressed, evaluated differently from the same behavior in men. Gabrielle notes that she is not as blunt in her anger as her heroine, Peppa, but instead tends to avoid conflict. I could relate, as I have the same issue with several of my heroines. Later in the interview, Gabrielle mentions that what distinguishes her antagonists from her protagonists is that the former use “some very blunt instruments” to attain their goals. These two comments got me thinking about how fiction is, in some respects, a way of exploring emotional paths not taken—for readers as well as for authors. In novels we can explore vengeance and murder, crises and conflict. We can talk back if we’re shy, beat our opponents up if we are timid or physically weak, flirt with infidelity or fall madly in love with characters who will never leave their socks on the floor or forget to pick us up at the airport. We can release the beast within—investigate it, test it, revel in it—without hurting ourselves or anyone else.

The same point applies to other art forms, of course: movies and television, especially. But well-crafted, well-written novels and short stories dump us inside another person’s head in ways that real life cannot, that even video cannot. We can see the world through the eyes of a falcon, a bad guy, an abandoned teenager, a runaway bride. We can experience life at the extremes, as most of us would much rather not do in real time. As Nancy Kress puts it in her wonderful Dynamic Characters , “In our lives we want tranquillity; in our fiction we want an unholy mess, preferably getting unholier page by page” (159).

And Peppa surely does get herself in an unholy mess, which gets unholier not only page by page but book by book. That’s why her story grabs us and doesn’t let go. But don’t take it from me: listen to the interview, then buy the book.

You can also hear (and in the case of The Falcon Flies Alone, read) an excerpt from the first two books at their respective pages on the Five Directions Press site: The Falcon Flies Alone and The Falcon Strikes .

As ever, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction (and is cross-posted to New Books in Fantasy and Adventure).

Peppa Mueller has a lot going for her. The daughter of a deceased Harvard professor who gave her an eclectic upbringing, she is heir to his fortune, and Radcliffe has accepted her application for undergraduate study in chemistry—her gift and her passion. Too bad that her conventional Swiss relatives cannot imagine why any young lady would want a college education in 1957.

Sick of their constraints, she runs away from their home in Basel, even though she cannot collect her inheritance for another two weeks. A house-sitting job draws her to a remote Alpine town, where she becomes the subject of a terrible experiment. Wanted for murder, accused of insanity, and beset by visions of herself as a fierce peregrine falcon, Peppa decides to go after Ludwig Unruh, the man who has victimized her and now holds her precious German Shepherd hostage to force Peppa to participate in his ongoing research into psychedelic plants.

But Unruh has far more experience with both chemistry and life than Peppa does, not to mention far fewer scruples. And as time goes on, she discovers that her past and his are inextricably intertwined. She wants to stop him, she wants to get herself and her dog out of his hands, but to do either, she must first survive his experiment. In The Falcon Flies Alone Gabrielle Mathieu, the host of New Books in Fantasy and Adventure, creates a compelling, fast-moving novel that straddles the line between reality and the world of the imagination.

Published on June 23, 2017 06:00

June 16, 2017

Rewind!

Few things are more satisfying to a writer or publisher than seeing a manuscript you’ve worked on for months or years appear in print. E-publication has its merits, and tablets and e-readers handle novels, which tend to have few images and simple formatting, with particular aplomb. Even so, it’s not like holding an actual book in your hands: admiring the cover, turning the pages, noticing the small details that say, yes, this is a published book.

Few things are more satisfying to a writer or publisher than seeing a manuscript you’ve worked on for months or years appear in print. E-publication has its merits, and tablets and e-readers handle novels, which tend to have few images and simple formatting, with particular aplomb. Even so, it’s not like holding an actual book in your hands: admiring the cover, turning the pages, noticing the small details that say, yes, this is a published book.So it’s always a special joy to announce a new work by one of our Five Directions Press authors. This month we focus on Denise Allan Steele’s new novel, Rewind, formally launched just yesterday. It’s charming, touching, hilarious—everything a novel should be.

Denise says she wrote the book because her kids begged for stories of the “olden days” (i.e., the 1970s) when she was a teenager in Scotland. The novel follows the adventures of Karen Anderson and her best friend, Carol, as they survive secondary school, attend college and nursing school, marry and have children, work in their chosen professions, move to different continents, and ultimately reunite at the funeral of Carol’s ninety-year-old Grandpa Jimmy, setting off the second half of the story.

But a summary can’t capture the joys of this delightful novel. So here is an excerpt from Chapter 1, “Abide with Me” (spelling is British Standard, because at least two-thirds of the novel takes place in Scotland):

Carol and I sat huddled together on the cold hard pew of Kilbrannan Parish Church. The weak sunshine coming through the huge stained glass window above our heads illuminated the figure of Saint Andrew, the ruby red of his gown beautiful and rich against the sapphire blue of the Scottish flag behind him. I had always loved that window, the way it gave me a feeling of peace and God and benevolence and contentment, the colours precious and magnificent in the austerity of the chilly old Presbyterian church. I had last seen the window from the inside in May 1977, when I had just turned fifteen. That was the day that Carol and I had been thrown out of the Girl Guides for refusing to say out loud the Brownie Guide promise that we would serve our God and our Queen. We felt that the Queen had enough servants and we definitely didn’t want to serve God, so we were asked to leave. We didn’t tell our mums and every Friday evening for months we had put on our Guide uniforms and gone to the amusement arcade at the beach, got changed in the toilets and hung about at the slot machines looking at boys and buying candy floss with our Guide money. Our sham was over when Mrs. Howie, the Guide leader, met Carol’s mum at the bus stop and our mums made us go the next Guide meeting and apologise.

I put my hand in Carol’s. “You okay?”

I hadn’t seen her since the last time I was home a year ago, and it felt like we had been together last week. Every time I came back to Kilbrannan, even after twenty-five years, it felt like I had been gone for a few days, and Carol and I just slotted back in to our lifelong friendship.

“Remember the last time we were in here and we got chucked out of the Guides?” She snorted, trying not to laugh. “And we had to go and apologise to that old bag Mrs. Howie. I still see her in the town, and she still glares at me, after thirty years!”

“Do you think that might be because you shouted ‘God save the Queen, the fascist regime’ at the top of your voice as we were running out of the church?”

Now, don’t you want to read more? You can find the book at Amazon.com or get more information at our Five Directions Press site. The book already has thousands of likes on Facebook, so don’t miss your chance to rewind the tape of Karen’s life—and your own.

Published on June 16, 2017 06:00

June 9, 2017

Anniversaries

Incredible as it may seem—it certainly seems so to me!—this month marks the fifth anniversary of this blog. If you had told me, in June 2012, that I would succeed in finding things to say every single week for five years, I would have wondered what mind-altering substance you had consumed. Yet here I am, five years on, occasionally frantic in my search for suitable topics for discussion but generally posting on time.

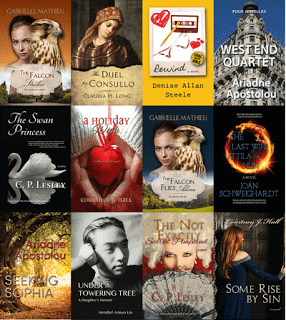

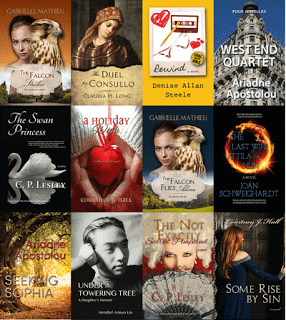

This month also marks the fifth anniversary of Five Directions Press. On June 3, 2012, we published the first version of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel (since reissued in a smaller size with a much spiffier cover designed by Courtney J. Hall). At the time, we saw our coop press as something of an experiment—a lark, even, like those old Mickey Rooney/Judy Garland films about putting on a show. We had only the vaguest idea of what we were doing, but the climate seemed right for a cooperative enterprise that lay somewhere between completely self-published and the commercial format monopolized by large corporate conglomerates. We gave it a try, not knowing what to expect, and it’s been great.

That first title has become twenty, out or due by early next year, as well as several more approaching completion but not yet ready to add to the website. (For those counting, Cover no. 20 is awaiting its big reveal next month before appearing on our Books page.) The latest went up on Amazon within the last twenty-four hours: stay tuned for that announcement next week. Our small group of three has tripled, and most of us have more than one book under our belts. Marketing is still a challenge, but we have learned lots about book production, publication, website design, newsletters and press releases, social media, even promotion. Two of us host podcasts on the New Books Network. And the topics of our books range from the dissolution of the Roman Empire to twenty-fourth-century ballet, with many highways and byways in between, and cover the globe from the secret Jewish communities of Inquisition-era Mexico to psychedelic experimentation in 1950s Switzerland.

Selected Five Directions Press BooksImage © 2017 Five Directions Press

Last but not least, June marks the ninth anniversary of the writers’ group that gave rise to Five Directions Press and produced most of its early titles. Each year at this time we go out to lunch, forget about the critiques, invite friends and fellow writers, and celebrate. That lunch is this weekend.

So a short post today to say that we’re enjoying the journey and to extend our thanks to our authors (who are also our staff), our indulgent families, and especially our readers. Let’s hope this is the first of many five-year anniversaries for Five Directions Press and its writers!

This month also marks the fifth anniversary of Five Directions Press. On June 3, 2012, we published the first version of The Not Exactly Scarlet Pimpernel (since reissued in a smaller size with a much spiffier cover designed by Courtney J. Hall). At the time, we saw our coop press as something of an experiment—a lark, even, like those old Mickey Rooney/Judy Garland films about putting on a show. We had only the vaguest idea of what we were doing, but the climate seemed right for a cooperative enterprise that lay somewhere between completely self-published and the commercial format monopolized by large corporate conglomerates. We gave it a try, not knowing what to expect, and it’s been great.

That first title has become twenty, out or due by early next year, as well as several more approaching completion but not yet ready to add to the website. (For those counting, Cover no. 20 is awaiting its big reveal next month before appearing on our Books page.) The latest went up on Amazon within the last twenty-four hours: stay tuned for that announcement next week. Our small group of three has tripled, and most of us have more than one book under our belts. Marketing is still a challenge, but we have learned lots about book production, publication, website design, newsletters and press releases, social media, even promotion. Two of us host podcasts on the New Books Network. And the topics of our books range from the dissolution of the Roman Empire to twenty-fourth-century ballet, with many highways and byways in between, and cover the globe from the secret Jewish communities of Inquisition-era Mexico to psychedelic experimentation in 1950s Switzerland.

Selected Five Directions Press BooksImage © 2017 Five Directions Press

Last but not least, June marks the ninth anniversary of the writers’ group that gave rise to Five Directions Press and produced most of its early titles. Each year at this time we go out to lunch, forget about the critiques, invite friends and fellow writers, and celebrate. That lunch is this weekend.

So a short post today to say that we’re enjoying the journey and to extend our thanks to our authors (who are also our staff), our indulgent families, and especially our readers. Let’s hope this is the first of many five-year anniversaries for Five Directions Press and its writers!

Published on June 09, 2017 06:00

June 2, 2017

The Shattered Drum

Although The Vermilion Bird is far from done, I have a complete story and am working on my fourth draft. A friend is checking the text for historical errors—or will be when she has the time. As I feed chapters to my writing group and receive comments, I make adjustments, of course, but since they too have busy lives and writing of their own, it will be three to four months before they can get to the end. So I decided, this past week, to use the down time to think about the next—and last—Legends novel.

Although The Vermilion Bird is far from done, I have a complete story and am working on my fourth draft. A friend is checking the text for historical errors—or will be when she has the time. As I feed chapters to my writing group and receive comments, I make adjustments, of course, but since they too have busy lives and writing of their own, it will be three to four months before they can get to the end. So I decided, this past week, to use the down time to think about the next—and last—Legends novel.Usually when I start a new project, it takes a good six months of back and forth before I make serious progress: planning, writing, research, rewriting, sharing, more rewriting, fill in the blanks research, character development, new writing, and so on. This in-between time seems the perfect opportunity to start planning a structure, identifying potential story elements, settling on major characters, defining their goals and motivations as well as the obstacles in their path—all the stuff that goes before actual writing begins. I’m not ready yet to shift my focus from the hero and heroine of Vermilion Bird, and without that, actual writing would be wooden at best. But I am ready to start imagining how the next, or in this case familiar, hero and heroine must struggle to reach a new set of goals.

Being a pantser by nature, as noted previously, I don’t get any closer to a detailed plot than a list of things I’d like to see happen. That changes as soon as I sit down to write. Still, having a sense of where I’m going is helpful, even if my characters do tend to take on lives and wills of their own. I love the surprises they deal out when I’m least expecting them. And having a sense of who those characters are at a given moment, even in a series that has already been underway for nine years, is a definite must—although that, too, evolves over time.

Here, in Legends 5, I find the list of story elements relatively easy to construct. A series can’t just stop, after all; it must tie up the major developments of the earlier books, adding a sense of general closure to the resolution every story needs even as it establishes a clear direction—beginning, middle, and end—of its own.

But I also find myself reluctant to say goodbye to these fictional people who, by the time I finish The Shattered Drum, will have enriched my life for over a decade. Can I bear to let them go? Will the new series slowly coalescing at the back of my brain, which follows into the 1540s and beyond certain characters who never received their due because the world isn’t quite ready for 1,500-page novels, make up for having to reduce my favorites to cameos and walk-ons?

But I also find myself reluctant to say goodbye to these fictional people who, by the time I finish The Shattered Drum, will have enriched my life for over a decade. Can I bear to let them go? Will the new series slowly coalescing at the back of my brain, which follows into the 1540s and beyond certain characters who never received their due because the world isn’t quite ready for 1,500-page novels, make up for having to reduce my favorites to cameos and walk-ons?I don’t know. In a sense, I’m not sure I want to find out. But that sad day remains a year or two away. For the moment, I’m looking forward to putting my fictional family through its paces one more time. I hope that one day, when I reach the end of that road, you’ll enjoy the results.

Images: Nomadic Girl, screen capture from Myn Bala; Butterfly and Chinese Wisteria Flowers, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on June 02, 2017 06:00

May 26, 2017

Sources and Stories

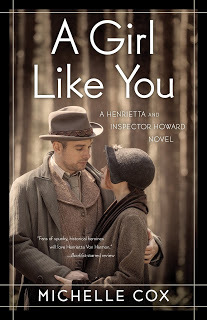

Even when I was young enough to think of everyone over thirty as a kind of antediluvian dinosaur, I always enjoyed hearing stories of the past from my elderly relatives and their friends. It seemed like opening a window on another world. So I was especially struck when I interviewed Michelle Cox—the author of

A Girl Like You

and

A Ring of Truth

, both romantic detective stories set in 1930s Chicago, with a third already on the way—to hear that many of the events that her heroine experiences come from stories told to her by a patient at the nursing home where Cox worked for a while.

Even when I was young enough to think of everyone over thirty as a kind of antediluvian dinosaur, I always enjoyed hearing stories of the past from my elderly relatives and their friends. It seemed like opening a window on another world. So I was especially struck when I interviewed Michelle Cox—the author of

A Girl Like You

and

A Ring of Truth

, both romantic detective stories set in 1930s Chicago, with a third already on the way—to hear that many of the events that her heroine experiences come from stories told to her by a patient at the nursing home where Cox worked for a while. All the no-longer-recognizable jobs—26 girl, taxi dancer, curler girl, usherette at a burlesque theater—as well as the all-too-familiar ones like floor scrubbing were held by this one patient, who, to paraphrase her words to Cox, also had “a man-catching body and a personality to match.” Given that the patient was in her eighties when she shared her story, we can only imagine what she was like in her teens, as Henrietta von Harmon, the heroine of this series, is when we meet her.

We talk about many other topics in the interview, including the road to publication, the fate of that first dreadful novel that writers inevitably have stashed in a drawer, and life during the Great Depression, as well as Henrietta and her fellow characters. But the lady behind the story is the part of the interview I didn’t and couldn’t anticipate. She gives a whole new meaning to the term “historical research.”

Indeed, I’m a little jealous. If only I could interview a real sixteenth-century Russian or Tatar.... Wouldn’t that be fun?

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

It’s January 1935. Prohibition has just ended, but the Great Depression has not, and much of Chicago remains under the grip of the crime lords who profited from the trade in illegal liquor. Eighteen-year-old Henrietta von Harmon, despite her aristocratic name, struggles to keep food on the table for her overwhelmed mother and seven younger siblings. After too many evenings spent cleaning, peddling drinks, and keeping score for dicers at a local bar, Henrietta jumps at the chance to double her income by taking a new job at a nightclub, where she dances with customers late into the evening. Too bad she cannot share the story with her family, who would be scandalized at the potential damage to her reputation if they knew. Then her boss turns up dead, and the customer to whom she is most attracted reveals that he works as a detective for the Chicago Police. The search for the murderer leads Henrietta into even more unsavory circumstances, and soon she’s wondering whether even the police can keep her safe.

In A Girl Like You and its sequel, A Ring of Truth, Michelle Cox introduces a rich cast of characters and a lovable heroine just trying to make her way in a cold and unforgiving world.

And for those of you who follow the interview participation of my cat, yes, he was there. He just decided to devote himself to purring that day instead of the usual piercing meows. Guess he liked the stories too!

Published on May 26, 2017 06:00

May 19, 2017

Writing Groups

Back in February, I wrote a post on how to avoid publishing before a book is ready. Near the end of that post, I recommended, among other things, finding a critique group of fellow writers. But what is a critique group? How is it organized? What does it do? Where would you find one?

The answer to most of those questions—excluding the last, in some ways the hardest—is “whatever you like.” So rather than get into all the possible variations, I restrict myself here to a brief overview of my own writing group, soon to celebrate its ninth anniversary.

We got started—and here is one answer to the “where?” question—when Ariadne and I independently joined a statewide writers’ organization. I saw that an open-forum writers’ group operated out of the local Borders (remember them?), but by the time I discovered the group’s existence, it had moved out of easy driving range. Through the statewide organization Ariadne, Courtney, and I eventually found one another, together with a fourth member who left after a couple of years, and our writing group was born.

We knew from the beginning that because we all wrote novels, we needed to be able to share at least a chapter at a time. So unlike the group that met at Borders, which had lots of people each exchanging five pages per month, we settled on no more than four people and a limit of thirty double-spaced pages, flexibly enforced depending on how many of us chose to share at a given meeting. Otherwise, we had only two basic rules: everyone must be actively writing; and barring an emergency, everyone must attend each session.

So what does that mean in day-to-day terms? Take Vermilion Bird, which has twenty-six chapters in the rough draft. After several months of not sharing, or sharing only an outline or character sketches or goal, motivation, and conflict charts, I moved into a regular rhythm of two chapters a month (25–35 pages). Up to this point, my critique partners have seen the first sixteen of the twenty-six, in some cases more than once. In particular, the crucial opening chapters took several rounds of suggestions to knock into shape.

This month, for example, I sent chapters 15 and 16, in the form of a Word document, to Ariadne and Courtney by e-mail two weeks ago. By the time we meet on Saturday, they will have read the chapters, probably more than once, and I will have read theirs. I expect to see a few comments on things they liked but also flagged passages that confused them, went on too long, verged on information dump, sounded “off” in terms of the dialogue, or—my particular bugbear because I was raised in chilly northern climes—included characters taking things far too calmly or behaving in ways better suited to an English drawing room than the Eurasian steppe.

I will take those comments, figure out how to respond without jeopardizing my inner vision of the story, and make changes. Then I will look at the chapters that follow to see how those changes ripple through the rest of the book, and revise those before sending the next two chapters for critique in June. If, as happened with chapter 15, a suggestion leads to a thorough rewrite, I may decide it’s best to share that chapter again. It’s hard enough juggling three different writers’ books over the course of a year or more without looking at a chapter that seems to bear no resemblance to the story one sort of remembers reading last time. At the end of the process, when the other group members have read all the chapters in ones and twos, we dedicate a meeting to one person’s work and read it from beginning to end to pick up continuity errors, repetition, missing setups, inconsistent characterization, and other issues that can slip from view during those thirty-page-at-a-time critiques.

The group—serious, as usual.

The group—serious, as usual.

What makes it work, more than anyone else, is the individuals involved. This is the factor in some ways least susceptible to control but most vital to a group’s success. We were lucky in that we turned out to be compatible, both in what we write and how we offer critique. An approach emphasizing the positive and offering suggestions without judgment or, worse, insult is essential. Grandstanding, posturing, and revenge games will kill a group before the members have a chance to figure out each person’s strengths and therefore which suggestions take priority.

A mix of strengths—plot first and character first, for example, or historical and literary—helps each member grow. The group will also function better if the members are at about the same stage of development; people writing their first paragraph can learn from writers with several novels under their belt, but they find it difficult to offer criticism and are easily intimidated, which throws off the balance of the group. A bad group can do more harm than no group, so this element of the decision should take precedence.

But assuming you can find the right emotional mix, what are the advantages and disadvantages of critique groups? Why would you want to consider one, and why might you instead prefer to seek out another way to improve your writing?

First, the advantages: I learned to write from working with others who were struggling with the same issues I was and who provided specific feedback on my specific story, rather than the generalizations that how-tos on the writing craft necessarily supply. It’s fun to talk to people who understand what you’re doing when you sit in front of the computer for hours on end or know how it feels to wake up in the middle of the night with characters jabbering in your head. And in those crucial early years, especially, writing is a lonely exercise with few rewards and fewer ways to separate the bad from the good in one’s own work. A writers’ group that fits your style offers a great way to test things out and learn, however slowly, what works and what doesn’t.

The disadvantages are not many, but they do exist. Even with our thirty-page limit, getting through an entire novel of three to four hundred pages takes a year or more, plus the final read-through and revisions. The input from the group—even a compatible group—can move a writer in a direction that may not fit an as yet hazy vision, requiring eventual push-back. On occasion, we get over-involved in one another’s work and have to disconnect, allowing the person writing the story to have the final word on its form and its content. None of these issues is fatal, but they do need management. For me, the end result of a better book and the pleasure of working with fellow writers who really know me, my strengths and weaknesses, and how I approach a project is worth the emotional investment of learning how to take (and give!) comments, but your calculation may not be the same.

There’s much more I could say, but this is a blog post, not a novel. What has your experience been? Have you ever joined a writers’ group? Did it work for you? Leave a comment below.

The answer to most of those questions—excluding the last, in some ways the hardest—is “whatever you like.” So rather than get into all the possible variations, I restrict myself here to a brief overview of my own writing group, soon to celebrate its ninth anniversary.

We got started—and here is one answer to the “where?” question—when Ariadne and I independently joined a statewide writers’ organization. I saw that an open-forum writers’ group operated out of the local Borders (remember them?), but by the time I discovered the group’s existence, it had moved out of easy driving range. Through the statewide organization Ariadne, Courtney, and I eventually found one another, together with a fourth member who left after a couple of years, and our writing group was born.

We knew from the beginning that because we all wrote novels, we needed to be able to share at least a chapter at a time. So unlike the group that met at Borders, which had lots of people each exchanging five pages per month, we settled on no more than four people and a limit of thirty double-spaced pages, flexibly enforced depending on how many of us chose to share at a given meeting. Otherwise, we had only two basic rules: everyone must be actively writing; and barring an emergency, everyone must attend each session.

So what does that mean in day-to-day terms? Take Vermilion Bird, which has twenty-six chapters in the rough draft. After several months of not sharing, or sharing only an outline or character sketches or goal, motivation, and conflict charts, I moved into a regular rhythm of two chapters a month (25–35 pages). Up to this point, my critique partners have seen the first sixteen of the twenty-six, in some cases more than once. In particular, the crucial opening chapters took several rounds of suggestions to knock into shape.

This month, for example, I sent chapters 15 and 16, in the form of a Word document, to Ariadne and Courtney by e-mail two weeks ago. By the time we meet on Saturday, they will have read the chapters, probably more than once, and I will have read theirs. I expect to see a few comments on things they liked but also flagged passages that confused them, went on too long, verged on information dump, sounded “off” in terms of the dialogue, or—my particular bugbear because I was raised in chilly northern climes—included characters taking things far too calmly or behaving in ways better suited to an English drawing room than the Eurasian steppe.

I will take those comments, figure out how to respond without jeopardizing my inner vision of the story, and make changes. Then I will look at the chapters that follow to see how those changes ripple through the rest of the book, and revise those before sending the next two chapters for critique in June. If, as happened with chapter 15, a suggestion leads to a thorough rewrite, I may decide it’s best to share that chapter again. It’s hard enough juggling three different writers’ books over the course of a year or more without looking at a chapter that seems to bear no resemblance to the story one sort of remembers reading last time. At the end of the process, when the other group members have read all the chapters in ones and twos, we dedicate a meeting to one person’s work and read it from beginning to end to pick up continuity errors, repetition, missing setups, inconsistent characterization, and other issues that can slip from view during those thirty-page-at-a-time critiques.

The group—serious, as usual.

The group—serious, as usual.What makes it work, more than anyone else, is the individuals involved. This is the factor in some ways least susceptible to control but most vital to a group’s success. We were lucky in that we turned out to be compatible, both in what we write and how we offer critique. An approach emphasizing the positive and offering suggestions without judgment or, worse, insult is essential. Grandstanding, posturing, and revenge games will kill a group before the members have a chance to figure out each person’s strengths and therefore which suggestions take priority.

A mix of strengths—plot first and character first, for example, or historical and literary—helps each member grow. The group will also function better if the members are at about the same stage of development; people writing their first paragraph can learn from writers with several novels under their belt, but they find it difficult to offer criticism and are easily intimidated, which throws off the balance of the group. A bad group can do more harm than no group, so this element of the decision should take precedence.

But assuming you can find the right emotional mix, what are the advantages and disadvantages of critique groups? Why would you want to consider one, and why might you instead prefer to seek out another way to improve your writing?

First, the advantages: I learned to write from working with others who were struggling with the same issues I was and who provided specific feedback on my specific story, rather than the generalizations that how-tos on the writing craft necessarily supply. It’s fun to talk to people who understand what you’re doing when you sit in front of the computer for hours on end or know how it feels to wake up in the middle of the night with characters jabbering in your head. And in those crucial early years, especially, writing is a lonely exercise with few rewards and fewer ways to separate the bad from the good in one’s own work. A writers’ group that fits your style offers a great way to test things out and learn, however slowly, what works and what doesn’t.

The disadvantages are not many, but they do exist. Even with our thirty-page limit, getting through an entire novel of three to four hundred pages takes a year or more, plus the final read-through and revisions. The input from the group—even a compatible group—can move a writer in a direction that may not fit an as yet hazy vision, requiring eventual push-back. On occasion, we get over-involved in one another’s work and have to disconnect, allowing the person writing the story to have the final word on its form and its content. None of these issues is fatal, but they do need management. For me, the end result of a better book and the pleasure of working with fellow writers who really know me, my strengths and weaknesses, and how I approach a project is worth the emotional investment of learning how to take (and give!) comments, but your calculation may not be the same.

There’s much more I could say, but this is a blog post, not a novel. What has your experience been? Have you ever joined a writers’ group? Did it work for you? Leave a comment below.

Published on May 19, 2017 08:44

May 12, 2017

Finding the Story

A couple of weeks ago, I announced on Facebook that I had finished the rough draft of Legends of the Five Directions 4: The Vermilion Bird. Social media being what they are, I’m assuming most readers of this blog didn’t see that post, which probably disappeared among the many other updates of their friends. But for me it marked the transition from the process of discovering whether I have a story to my favorite part of writing: the first revision stage.

A couple of weeks ago, I announced on Facebook that I had finished the rough draft of Legends of the Five Directions 4: The Vermilion Bird. Social media being what they are, I’m assuming most readers of this blog didn’t see that post, which probably disappeared among the many other updates of their friends. But for me it marked the transition from the process of discovering whether I have a story to my favorite part of writing: the first revision stage.This may seem like an odd preference. Isn’t the first draft more fun? Well, in some ways, yes. If I could outline worth a darn and stick to the plan, no doubt I would like that first run-through best. In the first draft the story is brand-new and shiny, and I follow the characters almost in awe as they come to life on the page.

But as I’ve confessed before, my outlines are sketchy at best. I try to have a plan for where I’m going, although I don’t always get there (Vermilion Bird is a perfect example: I had a reasonable sense of where my main couple would end up, but several other characters kept me in suspense almost until the last chapter). Sometimes I also draw up a list of midpoints to keep the book focused, but usually that’s a waste of time, since by the time I hit page ten, someone has done something unexpected and there I am, back in the woods. And while the exploration is a blast, and I learn what’s going to happen as I go along, the nagging sense that I may never reach the end or even have a story, in the sense of a well-connected tale that starts off one place and ends up farther along the same path, gives the whole process a somewhat frantic air.

As a result, I like the second draft best. By then, the general arc of the book is in place. I understand who the characters are, what pleases and worries them, what they recognize as troubling and what they have buried so deeply that only the developing story events can bring the truth to light. Of course, there are byways—and even highways—that go nowhere and people who show up in chapter 15 and have to be introduced earlier, details I forgot were already covered and others that somehow slipped through the cracks. But the trunk of the book exists, and the rest is a matter of pruning and grafting, planting and uprooting. At this point I go through the novel several times as quickly as I can, adding and subtracting until I have a more or less clean line from beginning to end.

As a result, I like the second draft best. By then, the general arc of the book is in place. I understand who the characters are, what pleases and worries them, what they recognize as troubling and what they have buried so deeply that only the developing story events can bring the truth to light. Of course, there are byways—and even highways—that go nowhere and people who show up in chapter 15 and have to be introduced earlier, details I forgot were already covered and others that somehow slipped through the cracks. But the trunk of the book exists, and the rest is a matter of pruning and grafting, planting and uprooting. At this point I go through the novel several times as quickly as I can, adding and subtracting until I have a more or less clean line from beginning to end.That is not the end of the revisions, by any means. I do individual runs for style, to remove clichés, to check for (historical, psychological, typographical) errors, to adjust for readers’ comments, to monitor that the dialogue sounds like something real people would say and excludes modern slang or post-medieval concepts of the universe. Only when I can’t think of anything else to fix does the book move toward publication. By then, I’m usually so sick of it that I can’t look at it anymore, at least for a while.

But that second round is special. The story is present but still new and exciting, rich with hidden depths and twists to uncover. It catches me up, to the point where I forgot to write this post yesterday. And now I have to get back to work. See you next week!

Images: Phoenix purchased from Shutterstock.com; Emperor Babur of India supervising work on his garden courtesy of the British Library.

Published on May 12, 2017 12:09

May 5, 2017

Tangled Webs and Shining Stars

Or, Why I loved West End Quartet

Or, Why I loved West End QuartetAs readers of this blog have probably figured out by now, I read a lot of books—and always have. Books are the focus of my work and fiction my chosen form of relaxation. I used to haunt bookstores the way “normal” people hang out in shopping malls, but these days many of my books come from Amazon.com, in print or e-versions.

Every single time I purchase or, especially, download a book, Amazon wants to know what I think of it. It even asks me to review my own books—which I don’t do. Sometimes I give in to the pleas, more often I don’t, but I’ve never had any trouble with getting Amazon to accept my feedback until this week, when I submitted a review of the latest Five Directions Press title, West End Quartet.

More specifically, Amazon thanked me for the review but never posted it. Clicking on the link gets me a cute dog photo and a “sorry, page not found” message. Clicking on the book link shows one review, not mine. What happened?

One explanation is a simple glitch. Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar, as the cliché has it. But it’s well known that Amazon can be suspicious about reviews that are perceived as coming from friends or family or fellow authors. So on the off chance that the review was in fact deleted due to some misunderstanding, let me take this opportunity to point out why I went out of my way to recommend West End Quartet to fellow readers at Amazon.

It was not because the author and I share a publisher or even belong to the same writers’ group, although we do. It was because the book is genuinely a wonderful read: rich in complex characters, evocative of a particular time and place, filled with brilliant settings and emotional experiences. I have watched it grow through many iterations, and I can attest that it has improved dramatically during that process. The author put a ton of work into crafting it, and those efforts have borne fruit. If you like foreign travel and reading about relationships among women, books about parenting, self-development, and the many different paths that people can take when they start in one place, then proceed in their own individual ways at their own pace toward maturity—this writer is for you.

Each of the first three novellas follows the divergent path of one member of the urban commune dubbed Group, formed in Manhattan in the late 1970s to promote feminist causes and fight nuclear power. Mallory joins the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, more out of love than conviction, and discovers that revolutions don’t roll along as smoothly as she expected; Mina abandons her Indian ashram for immigration law and a family, only to realize that a path to happiness can take very strange forms; Gwen, an academic star at the height of her career, revisits her own past and rediscovers the self she always wanted to be. In “Reunions,” the three women reconnect with Kleio Platon—the protagonist of the author’s first novel, Seeking Sophia, and the fourth member of Group—but the narrator for the novella is Mina’s daughter, Skye, shipped off to Greece as an au pair for Kleio’s daughter, Sophia, and in major culture shock through much of her story.

As one would expect of a character-focused writer, each story has its own tone, its own vocabulary, its unique approach. But the four novellas, like Seeking Sophia before them, are alike in their wonderful prose, like the passage quoted below, in which Skye discovers that things are not always what they seem.

Now admit: don’t you want to know more?

Excerpt from “Reunions,” part 4 of Ariadne Apostolou’s West End Quartet

They meander slowly up the road because it’s 115 degrees, an oven. The air just sits on you, a dead weight. Watch out for killer bees droning around like MiG-25 Interceptors, even if they look half dead from the heat, too.

Oh-ho. Behold the Dog!

Seeing Skye, the gigundo creature bares its saliva-dripping fangs, stands its ground in the middle of the road, head and tail lowered. Ears flare. A low growl escalates into a warning bark. Drool.

“Hey! It’s Mavri! Ella tho, Mavri!” Sophia bends on one knee to its eye level. At the sound of Sophia’s voice, ferocious Mavri morphs into a frisky puppy, lifts her head, yelps and raises her tail in a wild waggle. Her fangs recede into a wide grin. She prances over like she wants to play, bumps her snout into Sophia’s outstretched palm. She presses her flank into Sophia’s side, tail gone completely crazy.

You can find out more at http://www.fivedirectionspress.com/west-end-quartet.

Published on May 05, 2017 06:30