C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 34

September 22, 2017

Interview with Steve Wiegenstein

Steve Wiegenstein, the author of three novels and a finalist for the first MM Bennetts Award in Historical Fiction in 2015 for This Old World, agreed to talk with me as he gets ready to release the third book in his Daybreak series. The Language of Trees comes out next Tuesday, September 26, and is already available for pre-order at Amazon.com (just click the link to find out more). And of course, read his answers below!

Steve Wiegenstein, the author of three novels and a finalist for the first MM Bennetts Award in Historical Fiction in 2015 for This Old World, agreed to talk with me as he gets ready to release the third book in his Daybreak series. The Language of Trees comes out next Tuesday, September 26, and is already available for pre-order at Amazon.com (just click the link to find out more). And of course, read his answers below!The Language of Trees is the third novel in your Daybreak series, following Slant of Light and This Old World. Could you give us a brief sketch of the background developed in those first two novels that will help readers approach The Language of Trees?The books interlock, but my overarching goal is to make each book a satisfying aesthetic experience in itself, so readers shouldn’t worry if they haven’t read the earlier ones; they can still enjoy the next one. That being said, here’s what happened in the first books. Charlotte Turner, along with her husband James, established the Daybreak community in the 1850s as an experiment in communal, egalitarian living on the order of Brook Farm and New Harmony. The colony attracts a wide range of idealists, but James’ personal failings reveal themselves as he develops autocratic tendencies and engages in an affair, which results in the birth of Josephine Mercadier. Charlotte emerges as the community’s true leader and manages to hold Daybreak together, but the coming of the Civil War sends the men off to fight while the women remain behind. After the war, James returns a broken man, but redeems himself by protecting Josephine from her violent stepfather, an act which results in his death. Charlotte, Charley Pettibone, and the other founders of Daybreak carry on.

You live in the Ozarks. You have an active outdoor life and a teaching career. What made you decide to write novels—especially novels about a utopian nineteenth-century community? And having decided, how did you go about mastering the craft?My mom was a writer, and I grew up admiring the art. In fact, the romantic ideal of the journalist-turned-novelist, embodied by writers like Stephen Crane and Ernest Hemingway, is what led me into journalism originally. I wrote a novel in my twenties but it wasn’t particularly good—it was poorly crafted and written for the wrong reasons. So I became a teacher, all the while continuing my craft with a lot of short stories. I grew interested in nineteenth-century utopias because they represent the distillation of American optimism, and I’ve done a good bit of scholarship on them. Then one day in late 2006 the idea of combining my passion for fiction with my understanding of utopias, and setting a series of novels in my home region, came to me like a flash. I’ve been working on this project just about every day since.

The Language of Trees brings to adulthood a new generation in Daybreak, which leads to a generational clash between the community’s founders and its heirs. One source of conflict is industrial development, which threatens the agricultural environment as well as the philosophy of the Daybreak community. What made you decide to explore this particular conflict, and what can you tell us about it as it plays out in your book?

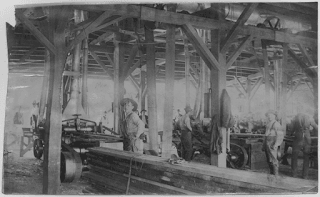

One thing I’ve learned about utopian communities is that communities founded by a charismatic or visionary leader rarely continue if that leader dies or becomes discredited. So I wanted to continue the story following the classic lifespan of utopias. Also, the 1880s saw the real boom of the Industrial Age, when it seemed as though moneyed interests were going to overwhelm all other elements of society, and there were efforts to resist that seemingly irresistible force. Nowadays we remember that as largely a labor-movement and progressive government resistance, but there was also a rural-urban dimension to that struggle that I wanted to capture. So it’s a very rich time period for exploration, and one that tends to get overlooked or oversimplified. I really think that the urban-rural divide that is so prominent today has its roots in the coming of industrial methods to rural life in the late nineteenth century. Another one of those “understand the present by understanding the past” opportunities!

One thing I’ve learned about utopian communities is that communities founded by a charismatic or visionary leader rarely continue if that leader dies or becomes discredited. So I wanted to continue the story following the classic lifespan of utopias. Also, the 1880s saw the real boom of the Industrial Age, when it seemed as though moneyed interests were going to overwhelm all other elements of society, and there were efforts to resist that seemingly irresistible force. Nowadays we remember that as largely a labor-movement and progressive government resistance, but there was also a rural-urban dimension to that struggle that I wanted to capture. So it’s a very rich time period for exploration, and one that tends to get overlooked or oversimplified. I really think that the urban-rural divide that is so prominent today has its roots in the coming of industrial methods to rural life in the late nineteenth century. Another one of those “understand the present by understanding the past” opportunities!As befitting a book about a communal utopia, your books trace the life of a community rather than focusing on one or two individuals. There are lots of point-of-view characters, who often see the world in contrasting ways. You do a remarkable job of keeping them both real and separate, but is it difficult to juggle so many different perspectives?It is, especially since there are times when several of them are in action simultaneously. I had to do a good bit of revision to make sure that I didn’t have a character in one place at the end of a day, and then magically appear in another place the next morning. But as you say, it’s the story of a community rather than an individual, so I thought that moving the point of view from character to character would be important in giving a sense of the totality of that experience. Flowing the action in and out of various characters’ minds is a challenge, but it’s also great fun! I hope readers will enjoy the ride.

Do you have a favorite character and story?Charlotte Turner has been my favorite since the beginning of the series. She’s a character who just keeps growing and changing as the series develops, in ways that I would not have predicted at first. Non-writers sometimes scoff at our claims that characters can develop and change in ways outside our conscious control, but I’m here to testify that it happens. Charlotte is tough beyond all reckoning, but she also has an immense capacity for love that keeps her going on despite all the struggles that life has given her.

As far as a storyline goes, I am awfully fond of Charley Pettibone’s. He started out in the first book as a goofy, illiterate orphan who more or less chanced into the community and who got caught up in the rush to glory that many young men experienced at the beginning of the Civil War. He came back from the war in the second book as a bitter, hardened young man who was at odds with everyone, but who discovered there were second chapters in life. And by The Language of Trees, he’s become someone who other characters look to for guidance. Of the various characters in the series, he may be the one who has grown the most.

What are you working on now?The fourth book in the series will take us into the twentieth century with a novel set in the years 1903–1904. That’s another endlessly interesting time period to me. Here in Missouri, it was the time of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, better known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. What a fascinating event! Intended as a celebration of American technological and racial superiority, it also revealed deep splits in the national mind. As an Ozarker, I’m also piqued by that period because it’s about then that the word “hillbilly” first came into use and the popular image of the Ozarks started to take shape.

Steve Wiegenstein was born and raised in the eastern Missouri Ozarks—his folks grew up on adjoining farms, and his family roots go deep in Madison, Iron, and Reynolds counties. He went to college at the University of Missouri. After a few years as a newspaper reporter, he returned to school and became a college professor. He is an avid canoer, rafter, and kayaker; a longtime member, friend, and supporter of the Quincy, IL, Unitarian Church; a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals; and a board member of the Missouri Writers' Guild. Learn more about him and his books at his website and blog.

Follow him on Facebook.

Image credit: “Men Standing in the Lumber Yard at the Ozark Lumber Co., Near Winona.” National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), no. 283583.

Published on September 22, 2017 06:00

September 15, 2017

Camels, Tea, and Steel-Tipped Parasols

In a pleasant surprise, the wonderful production people at the New Books Network posted my interview with Joan Hess within twenty-four hours.

In a pleasant surprise, the wonderful production people at the New Books Network posted my interview with Joan Hess within twenty-four hours.Some of you may know Joan Hess as a prolific writer of contemporary mysteries, many of them featuring Claire Malloy and another series set in the fictional town of Maggody. But Joan Hess was also a friend of Barbara Mertz, the Egyptologist turned novelist whom I memorialized in “The Sands of Time.” In that post I lamented several characters whom Barbara Mertz created under the pen name of Elizabeth Peters: most notably, Amelia Peabody; her husband, Radcliffe Emerson; and their son, Walter Peabody Emerson, better known as Ramses.

Well, it turns out I mourned their disappearance prematurely. As detailed in the interview, Joan Hess agreed after many refusals to take on the task of completing her friend’s final manuscript, about one-third of which Barbara/Elizabeth had finished before she died. The result is The Painted Queen —a rollicking adventure in the true Elizabeth Peters style that mixes archaeology, criminal activities, murder, and a series of bizarre but engaging twists that involve monocles, camels, and a writer of bodice rippers.

I understand perfectly why Joan Hess resisted the call. How do you finish another person’s manuscript, no matter how well you knew that person or how many scribbled notes she left (many of them illegible, it turns out)? Each author’s style is her own, and if you write contemporary mysteries set in small-town America and your friend uses her vast experience of archaeological digs to produce books set in Victorian and Edwardian England and Egypt, that gap between approaches becomes enormous. As much as I enjoy reading the books that emerge from my writers’ group and coop press, I can’t imagine taking over sparkling holiday romances, edgy historical fantasy with a psychedelic twist, intense character studies of contemporary women’s lives, or the many other works that my friends regularly write. No doubt they would balk at finishing a book inspired by four decades of researching medieval Russia.

Yet it’s to Joan Hess’s credit that she not only took on the project despite her doubts but completed it regardless of the very real stresses imposed by life. The Painted Queen is a beautiful tribute to a beloved author, but it is also a testament to the dedication required to write while mourning the friend whose work sits in front of you every day, demanding that you imagine how that friend would tackle the situations she created and how you can change things (because for sure, she would have changed things during the writing) to enhance the story without distorting its essence, to allow a large set of established characters to grow and develop yet remain true to themselves.

It’s also a darned good story. I learned a lot during this interview—about Barbara Mertz and her flagship series, of course, but also about the complexity of writing under a particular set of circumstances. Although I doubt I could have done the same, I’m very glad that Joan Hess did.

In a small change from my usual style, I am reproducing only part of the post that first aired on New Books in Historical Fiction. I expanded the first part into the longer discussion above.

In this last adventure, set in 1912, Peabody and Emerson have barely set foot in Cairo before the first death occurs: an unknown man wearing a monocle who collapses just inside the door of the bathroom where Peabody is soaking off the grime of her train ride from Alexandria. There is no question that the death is murder, and discovering the identity of the corpse, the reason for his carrying a card bearing the single word “Judas,” and the hand behind the knife that has dispatched the unwanted visitor consumes Peabody and Emerson even as they devote some of their attention to the excavation that has brought them to Egypt. The murderer could be the Master Criminal, defending Peabody from harm. Or s/he could be the representative of a secret society of monocle wearers, bent on revenge.

As Peabody and Emerson, with help from the junior members of their extended family, strive to figure out what’s going on, they must also deal with less deadly intrusions from a missionary named Dullard and the ineffable Ermintrude de Vere Smith, writer of racy romance novels, as well as a disappearing archeologist and an apparently nonstop succession of forgeries purporting to be statues of Nefertiti—the Painted Queen. It all makes for a deliciously entertaining sendoff to a much beloved series, one that Peabody and Emerson fans should not miss.

Published on September 15, 2017 06:00

September 8, 2017

The Vanishing Gallery

As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, no matter how hard historical novelists strive to portray their fictional worlds with accuracy, that goal is elusive. Readers usually blame the novelist for errors of omission or commission, and for sure some writers wouldn’t recognize research if it hit them with the proverbial barge pole. Others justify any stretching of the facts by citing the need to tell a good story. This approach, more than any other factor, explains the tendency among academic historians to sniff at historical fiction and those who produce it.

But this response does not do justice to the many historical novelists who do try hard to avoid anachronisms, even in the speech and thoughts of their characters. Furthermore, it ignores an even more fundamental problem: the real gaps that exist in our knowledge of the past.

In my interview a couple of weeks ago with Linnea Hartsuyker we talked about how remarkable it is that she can trace her ancestry through documentation back to the year 1000, although even in Norway most of our current information about daily life in the ninth and tenth centuries comes from archaeology, not documents. I mentioned then how impossible such a genealogical exercise would be in Russia, where even the earliest chronicles exist in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century copies. Only a handful of religious miscellanies survive from the Kievan period (862–1240 AD).

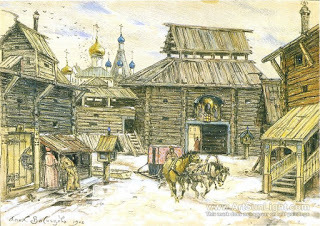

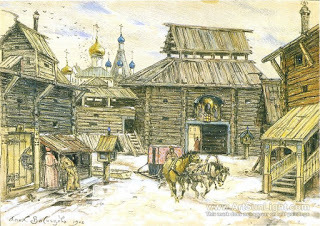

The problems don’t stop there. For obvious reasons, well into the sixteenth century (and up to the present in the rural areas that constitute most of the country) the primary building material in Russia was wood. That applied to Moscow as much as anywhere else, although the Kremlin acquired stone walls in the mid-fourteenth century and the familiar brick silhouette in the fifteenth. More and more churches, monasteries, and fortresses were built in stone or brick as time went on, and even the occasional domestic estate: the Old English Court and the house in which Tsar Mikhail Romanov (r. 1613–1645) was born are two sixteenth-century examples that have survived to the present day. But the vast majority of dwellings and shops in Moscow were made of wood. As a result, huge fires swept the city every twenty to thirty years, consuming not only lives and property but records. Historians of medieval Russia struggle with gaps and losses in the documentation every day. So too do historical novelists.

The problems don’t stop there. For obvious reasons, well into the sixteenth century (and up to the present in the rural areas that constitute most of the country) the primary building material in Russia was wood. That applied to Moscow as much as anywhere else, although the Kremlin acquired stone walls in the mid-fourteenth century and the familiar brick silhouette in the fifteenth. More and more churches, monasteries, and fortresses were built in stone or brick as time went on, and even the occasional domestic estate: the Old English Court and the house in which Tsar Mikhail Romanov (r. 1613–1645) was born are two sixteenth-century examples that have survived to the present day. But the vast majority of dwellings and shops in Moscow were made of wood. As a result, huge fires swept the city every twenty to thirty years, consuming not only lives and property but records. Historians of medieval Russia struggle with gaps and losses in the documentation every day. So too do historical novelists.

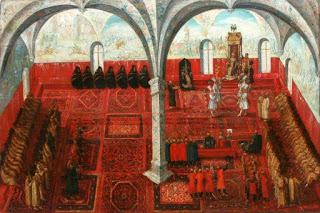

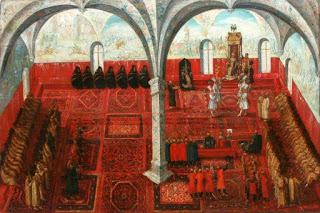

Take, for example, the Moscow Kremlin. If any place in Russia should have a voluminous and relatively complete history, it is this one. Yet basic questions about what existed when remain unanswered. The historian who checked The Vermilion Bird (as well as The Winged Horse and The Swan Princess—I am deep in her debt) for errors of fact mentioned the existence of a shielded viewing area from which royal women and children could observe ceremonies in the Palace of Facets, the main reception area for Muscovite grand princes and tsars. We know it was there in the seventeenth century, because the mother and half-sister of Peter the Great watched plays in the Palace of Facets while hidden from view. It appears also to have been used as a musicians’ gallery.

But did it exist in 1537? No amount of research and pleading on my part has so far answered that question. Although the seventeenth-century plays were a European import not known before the Time of Troubles (1598–1613), there were other reasons why such a viewing area might have been regarded as important in the 1530s: not least the dynastic reality that Grand Prince Ivan IV (later crowned as the first tsar and better known as “the Terrible”) had come to the throne in 1533 at the age of three, and his mother, although not a regent in the full European sense, had managed to overcome the many strictures on women and maneuvered her way into power. But even she could not receive foreign envoys or preside over meetings of the most powerful nobles, so she had every incentive to authorize the building of a structure where she could observe without being seen.

But did it exist in 1537? No amount of research and pleading on my part has so far answered that question. Although the seventeenth-century plays were a European import not known before the Time of Troubles (1598–1613), there were other reasons why such a viewing area might have been regarded as important in the 1530s: not least the dynastic reality that Grand Prince Ivan IV (later crowned as the first tsar and better known as “the Terrible”) had come to the throne in 1533 at the age of three, and his mother, although not a regent in the full European sense, had managed to overcome the many strictures on women and maneuvered her way into power. But even she could not receive foreign envoys or preside over meetings of the most powerful nobles, so she had every incentive to authorize the building of a structure where she could observe without being seen.

In the absence of definite information I decided to use the gallery in The Vermilion Bird. It so perfectly solves a problem for that story, and the solution to that problem could only be manufactured in any event. So as always, I include a disclaimer in the historical note. It is the luxury of fiction, when history fails us, to invent this detail or that.

But rest assured, I prefer the truth. I think many historical novelists feel the same. And many, many thanks to the historians who went out of their way to help me ascertain what that truth might be, even if in the end we had to conclude that the evidence just wasn’t there.

Images: Viktor Vasnetsov, The Seventeenth-Century Kremlin in Moscow (1913), public domain via Pinterest; Szymon Boguszowicz, Reception of the Polish Envoys by False Dmitry I (1606), showing the interior of the Palace of Facets, apparently as viewed from above, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

But this response does not do justice to the many historical novelists who do try hard to avoid anachronisms, even in the speech and thoughts of their characters. Furthermore, it ignores an even more fundamental problem: the real gaps that exist in our knowledge of the past.

In my interview a couple of weeks ago with Linnea Hartsuyker we talked about how remarkable it is that she can trace her ancestry through documentation back to the year 1000, although even in Norway most of our current information about daily life in the ninth and tenth centuries comes from archaeology, not documents. I mentioned then how impossible such a genealogical exercise would be in Russia, where even the earliest chronicles exist in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century copies. Only a handful of religious miscellanies survive from the Kievan period (862–1240 AD).

The problems don’t stop there. For obvious reasons, well into the sixteenth century (and up to the present in the rural areas that constitute most of the country) the primary building material in Russia was wood. That applied to Moscow as much as anywhere else, although the Kremlin acquired stone walls in the mid-fourteenth century and the familiar brick silhouette in the fifteenth. More and more churches, monasteries, and fortresses were built in stone or brick as time went on, and even the occasional domestic estate: the Old English Court and the house in which Tsar Mikhail Romanov (r. 1613–1645) was born are two sixteenth-century examples that have survived to the present day. But the vast majority of dwellings and shops in Moscow were made of wood. As a result, huge fires swept the city every twenty to thirty years, consuming not only lives and property but records. Historians of medieval Russia struggle with gaps and losses in the documentation every day. So too do historical novelists.

The problems don’t stop there. For obvious reasons, well into the sixteenth century (and up to the present in the rural areas that constitute most of the country) the primary building material in Russia was wood. That applied to Moscow as much as anywhere else, although the Kremlin acquired stone walls in the mid-fourteenth century and the familiar brick silhouette in the fifteenth. More and more churches, monasteries, and fortresses were built in stone or brick as time went on, and even the occasional domestic estate: the Old English Court and the house in which Tsar Mikhail Romanov (r. 1613–1645) was born are two sixteenth-century examples that have survived to the present day. But the vast majority of dwellings and shops in Moscow were made of wood. As a result, huge fires swept the city every twenty to thirty years, consuming not only lives and property but records. Historians of medieval Russia struggle with gaps and losses in the documentation every day. So too do historical novelists.Take, for example, the Moscow Kremlin. If any place in Russia should have a voluminous and relatively complete history, it is this one. Yet basic questions about what existed when remain unanswered. The historian who checked The Vermilion Bird (as well as The Winged Horse and The Swan Princess—I am deep in her debt) for errors of fact mentioned the existence of a shielded viewing area from which royal women and children could observe ceremonies in the Palace of Facets, the main reception area for Muscovite grand princes and tsars. We know it was there in the seventeenth century, because the mother and half-sister of Peter the Great watched plays in the Palace of Facets while hidden from view. It appears also to have been used as a musicians’ gallery.

But did it exist in 1537? No amount of research and pleading on my part has so far answered that question. Although the seventeenth-century plays were a European import not known before the Time of Troubles (1598–1613), there were other reasons why such a viewing area might have been regarded as important in the 1530s: not least the dynastic reality that Grand Prince Ivan IV (later crowned as the first tsar and better known as “the Terrible”) had come to the throne in 1533 at the age of three, and his mother, although not a regent in the full European sense, had managed to overcome the many strictures on women and maneuvered her way into power. But even she could not receive foreign envoys or preside over meetings of the most powerful nobles, so she had every incentive to authorize the building of a structure where she could observe without being seen.

But did it exist in 1537? No amount of research and pleading on my part has so far answered that question. Although the seventeenth-century plays were a European import not known before the Time of Troubles (1598–1613), there were other reasons why such a viewing area might have been regarded as important in the 1530s: not least the dynastic reality that Grand Prince Ivan IV (later crowned as the first tsar and better known as “the Terrible”) had come to the throne in 1533 at the age of three, and his mother, although not a regent in the full European sense, had managed to overcome the many strictures on women and maneuvered her way into power. But even she could not receive foreign envoys or preside over meetings of the most powerful nobles, so she had every incentive to authorize the building of a structure where she could observe without being seen.In the absence of definite information I decided to use the gallery in The Vermilion Bird. It so perfectly solves a problem for that story, and the solution to that problem could only be manufactured in any event. So as always, I include a disclaimer in the historical note. It is the luxury of fiction, when history fails us, to invent this detail or that.

But rest assured, I prefer the truth. I think many historical novelists feel the same. And many, many thanks to the historians who went out of their way to help me ascertain what that truth might be, even if in the end we had to conclude that the evidence just wasn’t there.

Images: Viktor Vasnetsov, The Seventeenth-Century Kremlin in Moscow (1913), public domain via Pinterest; Szymon Boguszowicz, Reception of the Polish Envoys by False Dmitry I (1606), showing the interior of the Palace of Facets, apparently as viewed from above, public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Published on September 08, 2017 12:37

September 1, 2017

The Falcon Strikes

It’s always exciting to announce a new book, especially an addition to a series one loves. So it’s a special pleasure to highlight Gabrielle Mathieu’s The Falcon Strikes in this week’s post.

For those of you who missed the first book, Mathieu’s Falcon trilogy features a gifted young woman named Peppa Mueller, who has been sent to Switzerland following the death of her father, a Harvard professor whose eccentric ideas on child rearing leave his daughter precociously competent in chemistry but ill equipped for the conventional lifestyle adopted by her Swiss relatives in 1957. When we meet her, Peppa has two weeks to wait until her twentieth birthday, when she can claim the fortune left to her by her father, kiss the relatives goodbye, and take up the place at Radcliffe that her aunt and uncle view as wholly unsuitable for a proper young lady. But involuntary exposure to hallucinogens sends Peppa off on a very different journey, one that connects her with her inner protective totem—a peregrine falcon.

The consequences of that journey mean that in book 2 Peppa regards herself as contaminated, a danger to the man she loves. When she learns that one of the people behind the hallucinogen experiment has traveled to Ireland, where the conflict between the Irish Republican Army and the British forces in Ulster has entered a new phase, off Peppa goes to spike her enemy’s guns. But the Irish conflict has twists and turns not easily understood by a young woman raised in the United States and Switzerland, even one with a grandmother living in a Galway castle. Despite Peppa’s efforts to contain her totem, she discovers that she must draw on the protection offered by the falcon to survive.

Find out more and listen to/read an excerpt at the Five Directions Press website. It is not necessary to have read The Falcon Flies Alone first to understand the sequel, but if you want to avoid spoilers, I recommend it.

You can also hear an interview with the author at New Books in Historical Fiction. And don’t miss Gabrielle Mathieu’s own website and blog, where she discusses the Falcon trilogy, what lies behind it, and the other books she has underway.

And now an excerpt from chapter 1 of The Falcon Strikes, “A Cold Awakening.”

I woke up from a muddle of dreams, heart pounding. Where was I?

In Ireland. I was in Dublin—I’d just arrived that morning.

I sensed an inert heavy body on the mattress.

The familiar sense of dread erupted. What had I done this time?

But it’s not you.

That was a matter of semantics. It was something in me. Educated society had no name for my condition. A witch doctor would have understood.

I was unpredictable. When threatened, my first instinct was to kill.

And I knew how to do it fast.

No stranger looking at me, a gawky twenty-year old girl with an appetite for Latin and chemistry, would guess that I could break someone’s neck as quick as a blink. It was an instinctive reaction to danger.

I lay still, afraid to look. My heart hammered in my chest, and perspiration drenched me.

Gabrielle Mathieu lived on three continents by the age of eight. She’d experienced the bustling bazaars of Pakistan, the serenity of Swiss mountain lakes, and the chaos of the immigration desk at the JFK Airport. Perhaps that’s why she developed an appetite for the unusual and disorienting. Her fantasy books are grounded in her experience of different cultures and interest in altered states of consciousness (mostly white wine and yoga these days). Five Directions Press published the first book in the Falcon trilogy, The Falcon Flies Alone, in 2016.

Gabrielle Mathieu lived on three continents by the age of eight. She’d experienced the bustling bazaars of Pakistan, the serenity of Swiss mountain lakes, and the chaos of the immigration desk at the JFK Airport. Perhaps that’s why she developed an appetite for the unusual and disorienting. Her fantasy books are grounded in her experience of different cultures and interest in altered states of consciousness (mostly white wine and yoga these days). Five Directions Press published the first book in the Falcon trilogy, The Falcon Flies Alone, in 2016.She is also the host of New Books in Fantasy and Adventure, a channel in the New Books Network.

Follow her on Twitter.

Like her on Facebook.

And definitely buy and read her books. As one reviewer put it, you’ll be in for “the flight of your life.”

Published on September 01, 2017 07:16

August 25, 2017

The Power of the Sea

Not too many people can trace their ancestry, through documents, back more than a millennium. Linnea Hartsuyker, my latest guest at New Books in Historical Fiction, is one of the few. When she was still in high school, her relatives set out to trace their ancestry and discovered that they were descended from Harald Fairhair, the first king of a united (or perhaps semi-united) Norway. From that past—and after a lot of research in Norse sagas, archeology, and much more, which we discuss during the interview—Linnea has crafted a trilogy set among her ninth-century ancestors.

The Half-Drowned King

appeared this month, The Sea Queen is scheduled for the summer of 2018, and The Golden Wolf will arrive a year later.

Not too many people can trace their ancestry, through documents, back more than a millennium. Linnea Hartsuyker, my latest guest at New Books in Historical Fiction, is one of the few. When she was still in high school, her relatives set out to trace their ancestry and discovered that they were descended from Harald Fairhair, the first king of a united (or perhaps semi-united) Norway. From that past—and after a lot of research in Norse sagas, archeology, and much more, which we discuss during the interview—Linnea has crafted a trilogy set among her ninth-century ancestors.

The Half-Drowned King

appeared this month, The Sea Queen is scheduled for the summer of 2018, and The Golden Wolf will arrive a year later.Harald Fairhair certainly appears in the series; Linnea describes him as a catalyst for the action. But the series focuses on Ragnvald, a young man who became Harald’s adviser; Ragnvald’s sister, Svanhild, desperate to escape an arranged marriage to an elderly neighbor; and Solvi, the trickster antagonist whose choices alternately aid and impede the quests of Ragnvald and his sister. These three, and the many other characters who cross their path, live in a richly detailed and imagined world governed by often erratic gods and goddesses who at times take a personal interest in their fates.

Linnea also maintains an active blog, where she discusses writing, her books, the pluses and minuses of an MFA, Viking culture, and many other things. So give our interview a listen, then follow up on the blog—and above all, if you like historical fiction with a touch of fantasy and a different approach, seek out The Half-Drowned King. And apologies for some lack of clarity in the sound: we were trying something new, designed to improve that very clarity, and it didn’t work as well as expected.

Linnea also maintains an active blog, where she discusses writing, her books, the pluses and minuses of an MFA, Viking culture, and many other things. So give our interview a listen, then follow up on the blog—and above all, if you like historical fiction with a touch of fantasy and a different approach, seek out The Half-Drowned King. And apologies for some lack of clarity in the sound: we were trying something new, designed to improve that very clarity, and it didn’t work as well as expected.As usual, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

Ragnvald Eysteinsson is returning from raiding in Ireland under the leadership of Solvi and focused on winning a contest with his fellow sailors when Solvi attacks. Ragnvald falls into the fjord and is given up for dead. But a fisherman pulls him out, and when Ragnvald recovers enough from his wounds and near-drowning to reach his home in southern Norway, he learns that his own stepfather paid Solvi to ensure that Ragnvald would never survive to reclaim the lands left him by his father. Cut off from home and family, denied the bride he was promised, Ragnvald sets out to recoup his fortunes and avenge his wrongs by swearing service for a year to Hakon, lord of a neighboring kingdom.

Meanwhile, Ragnvald’s sister has her own issues with their stepfather—most notably, his plans to marry her off to a rich elderly neighbor. A handsome young seafarer catches her eye. Unfortunately for them both, the seafarer is Solvi …

In The Half-Drowned King, the first book in a trilogy, Linnea Hartsuyker provides a richly detailed and captivating portrait of three young people whose hearts war with their loyalties in the turbulent period leading up to the establishment of the first united Norwegian kingdom.

Published on August 25, 2017 06:00

August 18, 2017

The Importance of Historical Novels

Today I’m delighted to welcome Octavia Randolph—the author of The Circle of Ceridwen Saga, now six bestselling volumes and counting—who in her guest post discusses the role of the Scandinavians in what is now the United Kingdom (and the fight against them) while exploring the deeper relevance of historical fiction as a whole.

Take it away, Octavia! And don’t forget to read down to the end of the page, where I tell you how to find out more about Octavia and her books.

The title above is a mildly provocative statement. But those amongst us who enjoy reading (and writing) historical fiction believe that good examples of the genre do far more than entertain. Well-written historical fiction can hand us a telescope to peer back into our own or another culture’s past. In a day when world history is given short shrift by many school systems, reading Dumas’ The Three Musketeers may be the only way to glimpse the dizzying complexity of seventeenth-century French political and social intrigue. Carefully researched historical fiction can educate and, even more excitingly, provoke speculation through original conclusions to historical puzzles. In Mary Renault’s brilliant The King Must Die and Bull from the Sea, she takes the classical hero Theseus and presents a wholly believable character whose strengths and flaws allow us to understand and even anticipate the heretofore inexplicable aspects of his behavior. His abandonment of the princess Ariadne on the island of Naxos is transformed from the disgraceful act of an ingrate (she has after all, helped him to triumph over the minotaur—in Renault’s book, a man, not man/beast) to an utterly correct and necessary action allowing both Theseus and Ariadne to come to their fullest potential.

Another way we know historical fiction is important is the firestorm of controversy it sometimes elicits. Isn’t there something remarkable about the fact that seventy years after it was written Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind was still powerful enough to provoke a response such as Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone? Described by its author as an “antidote,” The Wind Done Gone is a retelling of Mitchell’s story, using many of the same characters—Art imitating Art.

Let’s turn now from the broad canvas to the intimate personal narrative, such as Jane Mendelsohn’s I Was Amelia Earhart. This slender book takes us inside the aviator’s mind, up to and including her experiences on the South Sea island where she and navigator Fred Noonan make their way after ditching their plane. With sensitivity and deftness it allows the reader imagined access into Earhart’s thoughts, and provides a form of emotional closure to the mystery of her disappearance. As in Renault’s books, solutions to unanswerable questions have been proposed, and the reader in encountering these solutions and examining their ramifications may find previously opaque eras or personalities resolving into sharp and even indelible focus.

My own fiction deals with a time seemingly far removed from our own. Late ninth-century Britain was largely composed of competing Anglo-Saxon kingdoms—people who knew Christianity, enjoyed good ale, composed epic poetry, and forged wondrous weapons and jewelry. Suddenly, and with increasing frequency, marauding heathen seafarers from first Norway and then Denmark began decades of terrifyingly violent predation upon the mostly agrarian Anglo-Saxons. Most of the predation was carried out by a people the Anglo-Saxons called Danes—they were in fact from the same areas of modern Northern Germany and Denmark that the Angles and Saxons had come from a few hundred years earlier. That is very meaningful to me as a novelist, that connection; and the ability to see in repeating cycles of invasion a mirrored view of one’s own history.

The Vikings originally wanted treasure, but later they also wanted something more precious—land. They wished to settle and live in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms they had toppled. Decades of warfare, appeasement, negotiation, and intermarriage of Saxons and Danes ensued. A new nation was slowly being forged—a process that, as we know from world history, is rarely comfortable for its participants. The examination of conflicting values, divided loyalties, and the thrust of opposing religious beliefs and practices are timeless and universal human themes and make a rich ground for the novelist’s imagination.

Original source material augments and fires that imagination. The primary document of the period is an invaluable record known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was begun in King Alfred’s (849–899) time and documents the known history of the nation year by year from the year one. It was continued right up to the twelfth century. We have in a precious single manuscript the saga Beowulf, which tells us much of Anglo-Saxon mores, warrior life, the roles of women, and much more. We have physical evidence—artifacts such as the magnificent Sutton Hoo Treasure, the burial goods of King Redwald, who died about 625. We have other grave finds from many Anglo-Saxon burial grounds and occasional finds such as weapons retrieved from rivers and bogs.

I’m also a great believer in looking at the artifacts and landscapes of the era whenever possible. Studying one beautiful brooch or fragment of embroidery or a pattern-welded sword or a cluster of clay loom weights in person conveys information and spurs the imagination in a way that no amount of looking at photos can.

And this is where, in the combination of reading and looking, you can make the informed imagining that is perhaps not documented but is more than likely. For instance, we know that in both pagan, that is earlier, Anglo-Saxon society and Viking society, the tribal leader—who was always a war chief—also served as a religious medium between his people and the gods, served as a priest in ceremonies and sacrifices. Sometimes sacrifices to ensure good harvest or success in battle would entail the sacrifice of animals and possibly even humans. That’s what we know. What we can see are finds of spear points, seaxes, swords, helmets, and other war gear—all tremendously valuable, precious even—which have been purposely bent or broken or otherwise rendered unusable, then deposited either into rivers or in shallow pits dug in bogs. This is where the informed imagining comes into play: these may be weapons that were sacrificed as thank-offerings for victory or weapons that have been “punished” for failing their owners. In historical fiction we have the luxury of drawing these sorts of conclusions, which is one of the reasons I prefer writing fiction to writing history.

And this is where, in the combination of reading and looking, you can make the informed imagining that is perhaps not documented but is more than likely. For instance, we know that in both pagan, that is earlier, Anglo-Saxon society and Viking society, the tribal leader—who was always a war chief—also served as a religious medium between his people and the gods, served as a priest in ceremonies and sacrifices. Sometimes sacrifices to ensure good harvest or success in battle would entail the sacrifice of animals and possibly even humans. That’s what we know. What we can see are finds of spear points, seaxes, swords, helmets, and other war gear—all tremendously valuable, precious even—which have been purposely bent or broken or otherwise rendered unusable, then deposited either into rivers or in shallow pits dug in bogs. This is where the informed imagining comes into play: these may be weapons that were sacrificed as thank-offerings for victory or weapons that have been “punished” for failing their owners. In historical fiction we have the luxury of drawing these sorts of conclusions, which is one of the reasons I prefer writing fiction to writing history.

This brings me to the unasked question: why do we write historical fiction? I mean, it’s set in history; we know how it turned out! The task is to show the utter inevitability of what happened, as in the books of Mary Renault, or how it almost did not happen or that it actually happened differently and the story has been altered either deliberately or through accretion over the years, such as Donna Cross’s Pope Joan, about a ninth-century female pope. History, as has been famously noted, is written by the victors. And in the form of historical fiction, which is sometimes referred to as “mirror history,” it can show an alternate history—as in a book built on the premise of what if Napoleon hadn’t lost at Waterloo.

But the real point is that even if you are writing about a time period or actor very well known, there is always deeper questions to be answered: the “understory.” The understory in The Circle of Ceridwen is: Who is My Enemy?

For more about the understory, see my “The Story within the Story.” And don’t forget to check out Octavia and her books at www.octavia.net. Many thanks, Octavia, for this fascinating discussion!

Take it away, Octavia! And don’t forget to read down to the end of the page, where I tell you how to find out more about Octavia and her books.

The title above is a mildly provocative statement. But those amongst us who enjoy reading (and writing) historical fiction believe that good examples of the genre do far more than entertain. Well-written historical fiction can hand us a telescope to peer back into our own or another culture’s past. In a day when world history is given short shrift by many school systems, reading Dumas’ The Three Musketeers may be the only way to glimpse the dizzying complexity of seventeenth-century French political and social intrigue. Carefully researched historical fiction can educate and, even more excitingly, provoke speculation through original conclusions to historical puzzles. In Mary Renault’s brilliant The King Must Die and Bull from the Sea, she takes the classical hero Theseus and presents a wholly believable character whose strengths and flaws allow us to understand and even anticipate the heretofore inexplicable aspects of his behavior. His abandonment of the princess Ariadne on the island of Naxos is transformed from the disgraceful act of an ingrate (she has after all, helped him to triumph over the minotaur—in Renault’s book, a man, not man/beast) to an utterly correct and necessary action allowing both Theseus and Ariadne to come to their fullest potential.

Another way we know historical fiction is important is the firestorm of controversy it sometimes elicits. Isn’t there something remarkable about the fact that seventy years after it was written Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind was still powerful enough to provoke a response such as Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone? Described by its author as an “antidote,” The Wind Done Gone is a retelling of Mitchell’s story, using many of the same characters—Art imitating Art.

Let’s turn now from the broad canvas to the intimate personal narrative, such as Jane Mendelsohn’s I Was Amelia Earhart. This slender book takes us inside the aviator’s mind, up to and including her experiences on the South Sea island where she and navigator Fred Noonan make their way after ditching their plane. With sensitivity and deftness it allows the reader imagined access into Earhart’s thoughts, and provides a form of emotional closure to the mystery of her disappearance. As in Renault’s books, solutions to unanswerable questions have been proposed, and the reader in encountering these solutions and examining their ramifications may find previously opaque eras or personalities resolving into sharp and even indelible focus.

My own fiction deals with a time seemingly far removed from our own. Late ninth-century Britain was largely composed of competing Anglo-Saxon kingdoms—people who knew Christianity, enjoyed good ale, composed epic poetry, and forged wondrous weapons and jewelry. Suddenly, and with increasing frequency, marauding heathen seafarers from first Norway and then Denmark began decades of terrifyingly violent predation upon the mostly agrarian Anglo-Saxons. Most of the predation was carried out by a people the Anglo-Saxons called Danes—they were in fact from the same areas of modern Northern Germany and Denmark that the Angles and Saxons had come from a few hundred years earlier. That is very meaningful to me as a novelist, that connection; and the ability to see in repeating cycles of invasion a mirrored view of one’s own history.

The Vikings originally wanted treasure, but later they also wanted something more precious—land. They wished to settle and live in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms they had toppled. Decades of warfare, appeasement, negotiation, and intermarriage of Saxons and Danes ensued. A new nation was slowly being forged—a process that, as we know from world history, is rarely comfortable for its participants. The examination of conflicting values, divided loyalties, and the thrust of opposing religious beliefs and practices are timeless and universal human themes and make a rich ground for the novelist’s imagination.

Original source material augments and fires that imagination. The primary document of the period is an invaluable record known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was begun in King Alfred’s (849–899) time and documents the known history of the nation year by year from the year one. It was continued right up to the twelfth century. We have in a precious single manuscript the saga Beowulf, which tells us much of Anglo-Saxon mores, warrior life, the roles of women, and much more. We have physical evidence—artifacts such as the magnificent Sutton Hoo Treasure, the burial goods of King Redwald, who died about 625. We have other grave finds from many Anglo-Saxon burial grounds and occasional finds such as weapons retrieved from rivers and bogs.

I’m also a great believer in looking at the artifacts and landscapes of the era whenever possible. Studying one beautiful brooch or fragment of embroidery or a pattern-welded sword or a cluster of clay loom weights in person conveys information and spurs the imagination in a way that no amount of looking at photos can.

And this is where, in the combination of reading and looking, you can make the informed imagining that is perhaps not documented but is more than likely. For instance, we know that in both pagan, that is earlier, Anglo-Saxon society and Viking society, the tribal leader—who was always a war chief—also served as a religious medium between his people and the gods, served as a priest in ceremonies and sacrifices. Sometimes sacrifices to ensure good harvest or success in battle would entail the sacrifice of animals and possibly even humans. That’s what we know. What we can see are finds of spear points, seaxes, swords, helmets, and other war gear—all tremendously valuable, precious even—which have been purposely bent or broken or otherwise rendered unusable, then deposited either into rivers or in shallow pits dug in bogs. This is where the informed imagining comes into play: these may be weapons that were sacrificed as thank-offerings for victory or weapons that have been “punished” for failing their owners. In historical fiction we have the luxury of drawing these sorts of conclusions, which is one of the reasons I prefer writing fiction to writing history.

And this is where, in the combination of reading and looking, you can make the informed imagining that is perhaps not documented but is more than likely. For instance, we know that in both pagan, that is earlier, Anglo-Saxon society and Viking society, the tribal leader—who was always a war chief—also served as a religious medium between his people and the gods, served as a priest in ceremonies and sacrifices. Sometimes sacrifices to ensure good harvest or success in battle would entail the sacrifice of animals and possibly even humans. That’s what we know. What we can see are finds of spear points, seaxes, swords, helmets, and other war gear—all tremendously valuable, precious even—which have been purposely bent or broken or otherwise rendered unusable, then deposited either into rivers or in shallow pits dug in bogs. This is where the informed imagining comes into play: these may be weapons that were sacrificed as thank-offerings for victory or weapons that have been “punished” for failing their owners. In historical fiction we have the luxury of drawing these sorts of conclusions, which is one of the reasons I prefer writing fiction to writing history.This brings me to the unasked question: why do we write historical fiction? I mean, it’s set in history; we know how it turned out! The task is to show the utter inevitability of what happened, as in the books of Mary Renault, or how it almost did not happen or that it actually happened differently and the story has been altered either deliberately or through accretion over the years, such as Donna Cross’s Pope Joan, about a ninth-century female pope. History, as has been famously noted, is written by the victors. And in the form of historical fiction, which is sometimes referred to as “mirror history,” it can show an alternate history—as in a book built on the premise of what if Napoleon hadn’t lost at Waterloo.

But the real point is that even if you are writing about a time period or actor very well known, there is always deeper questions to be answered: the “understory.” The understory in The Circle of Ceridwen is: Who is My Enemy?

For more about the understory, see my “The Story within the Story.” And don’t forget to check out Octavia and her books at www.octavia.net. Many thanks, Octavia, for this fascinating discussion!

Published on August 18, 2017 06:00

August 11, 2017

Interview with Sarah Zama

I rarely have two author interviews back to back—in fact, I can’t think of another time in the five years that I’ve maintained this blog—but it just so happened that I read both The Dress in the Window and Give in to the Feeling within a few days of each other. And I had a chance to interview both authors, so I saw no reason to make either of them wait.

I rarely have two author interviews back to back—in fact, I can’t think of another time in the five years that I’ve maintained this blog—but it just so happened that I read both The Dress in the Window and Give in to the Feeling within a few days of each other. And I had a chance to interview both authors, so I saw no reason to make either of them wait.Sarah Zama is just beginning as a published writer; she is currently working on a trilogy about the characters whom she introduces in Give in to the Feeling, a novella set in 1920s Chicago. So this book is also one of my Hidden Gems—short but sweet, in this case, and a great way to become acquainted with Sarah’s writing. Moreover, it too offers an inspiring story. You can find out more about Sarah and her books at her website, http://theoldshelter.com.

What drew you to this story, which you describe as fantasy dieselpunk? For starters, what is fantasy dieselpunk?I’m not surprised that you’re asking. Many readers (and authors) are unaware of this genre.

The easiest way to describe dieselpunk is: it’s like steampunk set in a more recent era, spanning from the late 1910s to the early 1950s. You have the aesthetics and the history of those decades, but with a twist (history gets punked, as we say) so that these stories are not really historicals even when (as in my case) they are very close to history.

Dieselpunk is such a young genre (the word itself was coined only in the 1990s) that not even us dieselpunks agree on what it is exactly. Many dieselpunks think that only Retrofuturism falls into the genre; we speak about stories that have a strong SF element to it (think The Rocketeer or Captain America: The First Avenger, to name a couple of films people might have seen). But some of us consider fantasy elements to be just as good for a dieselpunk story (think Indiana Jones).

I’ve always been drawn to stories with a twist, stories that have a fantasy element in them. I’ve always been drawn to fantasy, actually. I was a Tolkien fan long before Peter Jackson’s film trilogy, and I’ve been a R. E. Howard fan even longer. But I’ve always loved early twentieth-century history too, especially the Deco years, so it was probably in the logic of things that I would end up mixing these two passions of mine.

I honestly discovered the 1920s by chance, but I’ve completely fallen in love with this era, because it has so many similarities with our own time.

You are preparing a trilogy that explores some of the same themes in this novella—and indeed, I often wanted to know more about the characters’ pasts. Which came first: the trilogy or the novella? But more generally, what draws you to the world of ghosts and spirits? The genesis of these stories is quite funny.

I started out wanting to write a series of novellas or short stories bound by a recurring cast of characters. I wanted to set it in the 1930s, but at the time I knew nothing—and I mean absolutely nothing—about that time. So I started planning the series, and at the same time I researched that period.

After a year of research, I shifted from the 1930s to the 1920s for a question of accuracy (couldn’t set a few ideas in the 1930s and still be accurate). I also had written zero words of the actual story. So I decided I needed to test my characters and my ideas, since I felt insecure that I could actually handle the time period. I wrote Give in to the Feeling as a character study, and it was such fun! I was already in love with these characters, but writing them made me love them even more.

So after that I wanted to test the setting a bit more. I outlined a trilogy of novellas which were still set earlier than the original idea, and I enrolled in National Novel Writing Month, which is a yearly challenge to write a novel of at least 50,000 words in the month of November. My plan was to write a detailed synopsis of the entire trilogy of novellas, which I estimated would take some 15,000–20,000 words total, and then write whatever I could of the actual novellas to reach the 50,000 words of the challenge.

Well, it didn’t exactly work like that.

The synopsis of Ghostly Smell Around, the first installment, ended up at 22,000 words. I completed NaNo halfway through the second installment, and at that point I understood my story had plans very different from mine about how it wanted to be told.

I completed the first draft of the trilogy in a couple of years. I revised it completely in a few more. Then I concentrated on the first novel. My plan was (and still is) to try to publish the trilogy traditionally, but I also wanted to try self publishing. So a couple of years ago I went back to Give in to the Feeling, rewrote it completely (because, as you may imagine, I had learned lots of things about these characters in the four years I had spent with them) and published it as an indie novella.

It was a fantastic adventure.

Why the world of spirits? I’ve always been fascinated with spirituality, with ghosts, with the possibility that there might be more than the physical world around us. Maybe because we live in such a materialistic world, I like to explore the possibility that there might be more, a place where what we are (our true soul) is more important of what we have.

Tell us about Susie, the main character. How did she end up in a Chicago speakeasy?In a very odd way, I’d say.

She’s a Chinese girl and she was sent out to be a mail-order wife, which was quite a common practice in immigrant communities in the first part of the twentieth century. But when she lands in San Francisco, she discovers that her prospective husband has died in the meanwhile and she is taken up by his young associate, which leads Susie to Chicago and sends her life in a much different direction. Simon is an ambitious man who wants to have a rich life. In Prohibition-era America he thinks bootlegging is a viable way to achieve his dream.

The first time I wrote Give in to the Feeling it was really mostly a character study, but the second time I wrote it I wanted it to be Susie’s story. I wanted to see her evolve and become her own woman, as she had the opportunity to be.

The 1920s were an exciting time to be a woman, though not in the way most people think. We often see the 1920s as a liberating time, which it was—to an extent. Flappers did break free from lots of the old bonds, but we should remember that many bonds still stood. We should also remember that most women weren’t flappers in the 1920s. Only young university girls, with money and time on their hands, could afford to be flappers. In spite of this, I do think that most women, especially young ones, aspired to be flappers or at least to be as free as the flappers showed they could be.

This is where the importance of the “flapper movement” (as it is sometimes termed) really lies: not in the achievements, which were limited in time and in some respect in magnitude, but in the breaking through. Its power came from showing a different way, not just to women but to men as well.

To some extent Susie walks the same path, passing through the “freedom” and excitement to show herself the way she wants, and coming in the end to a more profound understanding of what freedom truly is.

And what of Simon? How does he fit into Susie’s life?Well, if I had to name the character that most evolved from the first version of the story to the published one, it would be Simon. In the first version, he was just the antagonist, but as I revised the novella for publication, I started wondering what drove him. From the beginning I didn’t want him to be a mere villain, but his reasons and his acting certainly became more nuanced and prominent as the story evolved.

I suppose Simon incarnates the danger of ambition not culled by ethics. There’s nothing wrong with what Simon wants, in my opinion, it’s what he’s willing to leave behind to achieve it that is problematic.

Simon is the only character that doesn’t appear in the other stories of this series, and I had a great time exploring him.

Trouble starts when two brothers, Michael and Blood, walk into the bar. Susie and Blood are instantly drawn to each other. What can you tell us about the brothers?I truly truly love these guys. Readers tell me it’s apparent, but I can’t do anything about it. Blood and Michael were the original idea, the reason why this series of stories exists. In fact, when I originally wrote Give in to the Feeling, I had a hard time keeping it as Susie’s story, because Michael and Blood kept trying to steal the stage.

I consider Ghost Trilogy as Michael’s story, so yes, there is a lot more to learn about him and Blood, their relationship and what caused Michael to flee the reservation. Deciding what to let filter into the novella and what to leave untold was like going through hell!

Michael and Blood are Lakota Ogalala. I’ve always been interested in the Native American cultures and spirituality, and this interest has deepened in the last decade. Still, I was very hesitant to handle Lakota characters because I had no direct contact with that culture (I was less hesitant with Susie because I have friends who are Chinese). I researched the hell out of it, but still I think this would have been a very different story and they would have certainly be very different characters if I hadn’t met someone who today is a dear friend on an online workshop for writers.

She’s Mohawk, actually, not Lakota, but she helped me get into Native American feelings and thinking in a way I could have never achieved on my own. I know it and I need to acknowledge it. And she’s a writer herself (she writes under the name Melinda Kelly), so meeting her was really the very best thing that could happen to me and my story!

The relationship between tradition and modernity and the survival of traditional practices and beliefs in the modern times is something very close to my heart. Native Americans stand in a peculiar position in this regard, and this may be what inspired me to have Lakota characters in my story. Most of my characters are liminal. They stand in the face of a new world (of change) but hesitate to step into it for fear of what that world may take from them. There’s Susie, who’s a Chinese in America; Sinéad, who’s an Irish immigrant; Angelo, who’s a third-generation Italian-American; and a lot of African American characters who live in the time of the Harlem Renaissance. But none of them express that hesitation in front of change and the urge to find a way to cope better than Blood and Michael, in my opinion.

When can we expect to see more of Susie’s story?Ghostly Smell Around, the first novel in the trilogy, is at the polishing stage, basically ready to go. I’m trying to get it published traditionally, but we know how these things go, so I may end up self-publishing it. Let’s see what happens.

The rest of the trilogy is written, although it stands at a second draft stage.

As I mentioned, Ghost Trilogy is more of Michael’s story, but Susie is important to it. In the trilogy, she’s a very strong character (Michael considers her to be bossy), who has found her balance in her relationship with Blood and is happy to be part of the Red Willow family. And after going though her own ordeal, in the trilogy Susie is a character who always strives to help others find their way in life and be happy.

I’m very proud of her.

Sarah, thank you so much for sharing your answers with me and my readers. Can’t wait for your Ghost Trilogy to appear!

BioA bookseller in Verona (Italy), Sarah Zama has always lived surrounded by books. Always a fantasy reader and writer, she’s recently found her home in the dieselpunk community. Her first book, Give in to the Feeling, came out in 2016.

Published on August 11, 2017 06:00

August 4, 2017

Interview with Sofia Grant

As you may have guessed from the post I wrote back in April about blue jeans, fashion is, to borrow a phrase from Sir Percy Blakeney, “not my forte.” So it rather surprised me how much I enjoyed Sofia Grant’s The Dress in the Window, which is, on the surface, all about the new styles in fashion that arrived in the wake of World War II.

As you may have guessed from the post I wrote back in April about blue jeans, fashion is, to borrow a phrase from Sir Percy Blakeney, “not my forte.” So it rather surprised me how much I enjoyed Sofia Grant’s The Dress in the Window, which is, on the surface, all about the new styles in fashion that arrived in the wake of World War II.Of course, like most good novels, The Dress in the Window actually explores much deeper themes than fabrics and styles: the importance of family, the long-term effects of the war, the establishment of identity in a changing world. Sofia Grant joins me today to talk about those elements of the book. You’ll find a link to the book in this paragraph and more information about the author at the end of the interview. You don’t even need makeup to read her answers, let alone fancy clothes—so enjoy!

This is your first book published under the name Sofia Grant, but not your first novel. What made you decide you needed a change of name?Historical fiction is a departure from the novels I’ve written in the past, and using a new author name is a way to signal to readers—both old and new—that they can expect something different this time around.

What made you want to set your story in this particular time and place?As a lifelong hobby seamstress and fashion buff, I can’t imagine a more exciting era in American fashion than after WWII! Women still sewed many of the clothes for their families, which appealed to me, as it gave me an opportunity to write about garment construction. (I know it sounds boring but it really is integral to my plot!) But couture fashion was changing as well, and the wealthy women who were accustomed to buying dresses in exclusive salons had also been affected and changed by the war.

At first I thought I would set my book in New York City, which was then the fashion hub of the country. But choosing a location close enough to commute, but far enough away to give me access to the mills and factories where clothing was made, proved far more interesting.

Although fashion provides the environment in which the novel takes place, this is really a story of a women-only family: Jeanne, Peggy, Thelma, and Tommie. Each character is beautifully defined and rich. Tell us first about the two sisters, Jeanne and Peggy. How do you see them as characters? How do you think about their relationship?Thank you for that lovely compliment! I am fond of both Peggy and Jeanne, and is often happens in my novels, I figured out after the story was written that they are an amalgam of some of my own traits. I’m creative and impulsive like Peggy but also a bit of a mother hen, as Jeanne becomes over time. Also, there are bits in the book inspired by my relationship with my younger sister. (Funny story—when I gave my sister a copy of the book to read, I had to reassure her that I wasn’t accusing her of being flighty like Peggy.)

Sister relationships in general are so interesting! I don’t think there’s a more intense emotional bond. Sisters can encourage or provoke each other so easily. Envy and competition are balanced by unbreakable devotion. As Peggy and Jeanne face the challenges of loss, grief, and poverty, I tried to show how they antagonize and support each other.

Thelma is the mother in this family, although she is not the actual mother of any of the others. What distinguishes her?I think it’s no accident that Thelma is around my age and—like me—is intensely maternal. Even when she wants to keep these young women at a distance, she is unable to stop herself from coming to love them.

She also has an unquenchable drive to not just survive but to drink deeply of life. I hope it’s not immodest of me to say that I modeled that characteristic after myself. Following my own midlife reinvention, I discovered I was not willing to settle for society’s notion of what it means to be a matron. Thelma takes her due, in secret when necessary. I admire that.

Tommie, because she is very young at the beginning of the story, necessarily has the least “voice” of the four. Yet she acts as a kind of anchor for the women, or perhaps a source of tension. How do you see her role in the book?I quite agree! Tommie becomes not just the glue holding the three women together but a driver for them all to try to be their best selves. I find that’s true in my life—in times of challenge, my own children have inspired the adults around them to try to pull together for the benefit of everyone.

Tommie is also a mirror for Peggy. In her daughter she sees a reflection of both her assets and her shortcomings, as well as an obstacle for her reaching her dreams. It is a singular cruelty of that era that women were expected to subvert their desires in service to domesticity and motherhood. Though Peggy strains against those bonds, she never truly abandons Tommie, and her love is constant.

Fabric itself seems at times almost to be an expression of the characters. Each chapter begins with a discussion of a specific fabric that has qualities explored in that chapter. Why did you decide to include that element?Well! I must say that was a bit of an indulgence, and I’ve been nervous about how it might be received. I love fabric, and my education came from my mother and grandmother, who were truly gifted seamstresses. So these passages are an homage to them, a nod to the happy hours I spent learning at their knees.

Yet I also know that this will be quite foreign to many readers, and I deliberated quite a bit before including them. They aren’t essential to understanding the story, but I hoped to do several things with these bits of text: both set the emotional tone for what comes after, and add a sensory element as well as a sense of historical accuracy.

What are you working on now?Thanks so much for asking! (And thank you, by the way, for inviting me to play.)

I’ve just turned in my next novel to the same editor who worked on The Dress in the Window. Her name is Lucia Macro, and she’s a true pleasure to work with, as well as very smart about bringing a story to life.

The new book, tentatively titled The Daisy Children, explores a real-life tragedy: in 1937, over three hundred Texan schoolchildren were killed in a gas explosion. But I use a contemporary storyline to explore the aftermath of the disaster, and created a cast of characters that I really enjoyed writing. There’s intrigue, passion, greed, vengeance, and even a bit of a love story. Fingers crossed!

Thank you so much, Sofia, for taking the time to answer my questions. I wish you all success with this book and the books to come. Readers can find out more about Sofia and her books at http://sofiagrant.com. There you can read, in addition to her official bio pasted in below, a longer piece about her writing career and how she got started. If you’ve ever thought about writing fiction, her story will inspire you.

BioCalled a “writing machine” by the New York Times and a “master storyteller” by the Midwest Book Review, Sofia Grant has written dozens of novels for adults and teens under the name Sophie Littlefield. She has won Anthony and RT Book Awards and been shortlisted for Edgar®, Barry, Crimespree, Macavity, and Goodreads Choice Awards. Sofia works from an urban aerie in Oakland, California.

Book DescriptionA perfect debut novel is like a perfect dress—it’s a “must have” and when you “try it on” it fits perfectly. In this richly patterned story of sisterhood, ambition, and reinvention Sofia Grant has created a story just right for fans of Vintage and The Dress Shop of Dreams.

World War II has ended and American women are shedding their old clothes for the gorgeous new styles. Voluminous layers of taffeta and tulle, wasp waists, and beautiful color—all so welcome after years of sensible styles and strict rationing.

Jeanne Brink and her sister Peggy both had to weather every tragedy the war had to offer—Peggy now a widowed mother, Jeanne without the fiancé she’d counted on, both living with Peggy’s mother-in-law in a grim mill town. But despite their grey pasts they long for a bright future—Jeanne by creating stunning dresses for her clients with the help of her sister Peggy’s brilliant sketches.

Together, they combine forces to create amazing fashions and a more prosperous life than they’d ever dreamed of before the war. But sisterly love can sometimes turn into sibling jealousy. Always playing second fiddle to her sister, Peggy yearns to make her own mark. But as they soon discover, the future is never without its surprises, ones that have the potential to make—or break—their dreams.

Published on August 04, 2017 06:00

July 28, 2017

It Runs in Families

You may remember that in February 2017 I posted about how I read and fell in love with Beatriz Williams’

A Certain Age

. So I found it particularly interesting to discover during my recent interview with Beatriz for New Books in Historical Fiction that the characters and fundamental romantic plot of that book derive from an opera that Beatriz knew growing up. (You can find out which opera and how the stories intersect by listening to the interview.)

You may remember that in February 2017 I posted about how I read and fell in love with Beatriz Williams’

A Certain Age

. So I found it particularly interesting to discover during my recent interview with Beatriz for New Books in Historical Fiction that the characters and fundamental romantic plot of that book derive from an opera that Beatriz knew growing up. (You can find out which opera and how the stories intersect by listening to the interview.)Also during the conversation, we talk quite a bit about how characters—even whole families—from one of her books pop up in other books. It’s a kind of in-group game: you read one, wonder what happened to X, and bang, there he or she is, starring in another. Or sometimes just making a cameo appearance, like Hollywood celebrities.

I have to admit that, although I wanted to hear why Beatriz recycles her fictional people in this way, I understand the urge completely. Not only do my Legends novels trace the development of a whole cast of friends and family members over the course of five years or so, but I have enough “leftover” potential heroines to people a second series of their own. Naturally, since they will still be moving forward in time, they will intersect with Nasan, Daniil, Ogodai, Firuza, Maria, Alexei, and the rest as seems appropriate. I have the sense I couldn’t stop them if I tried.

So what is the attraction of sticking with an expanding group rather than starting afresh each time as most novelists do? Again, Beatriz explains her reasons in the interview. Mine follow here.

At the most basic level, I envisioned the series that way, but in the early days of writing I failed to understand how simple novel plots need to be, so I had too many characters with too many stories for any one book. These are the “leftovers,” whose backgrounds I know and whose development I have imagined but whose stories didn’t fit into the space available.

A second reason is that known characters come with some of the prep work already done. A writer has to figure out how to grow them, both as individuals and in terms of their relationships, but developing an existing character is easier than starting from scratch. It takes a long time to build a consistent but well-rounded character, so why waste the effort?

Last, for me and for Beatriz as well, those existing characters constitute a story world, filled with the complexities that we find in the real world. They are, if you like, a reflection of a given author’s personality. And like the real world, there are always surprises waiting around the corner, questions demanding answers and people eager to reveal hidden facets of themselves.

So long as the journey entertains and enlightens, we may as well continue along the same path. Because given the way the subconscious works, when that path ceases to lead anywhere, the inspiration will dry up and a new character will force him- or herself into the writer’s mind, insisting on telling his or her story.

Then, like it or not, off we plunge into another story world filled with a different cast. With luck, they too will become friends and family by the time their saga comes to an end.