C.P. Lesley's Blog, page 31

April 20, 2018

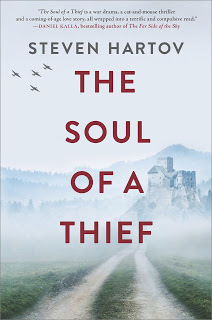

Interview with Steven Hartov

This has been a strange year for historical fiction, at least as it relates to my podcast. After five years of ranging over as many time periods and regions of the globe as possible, I find myself staring in somewhat befuddled manner at a roster that consists almost entirely of US history and novels about World War II. How that came to be I am not sure—certainly not by intent! But so it is.

This has been a strange year for historical fiction, at least as it relates to my podcast. After five years of ranging over as many time periods and regions of the globe as possible, I find myself staring in somewhat befuddled manner at a roster that consists almost entirely of US history and novels about World War II. How that came to be I am not sure—certainly not by intent! But so it is.This statement is not intended to reflect on the novels themselves, most of which are excellent. Today I’m discussing Steven Hartov’s The Soul of a Thief , which I also picked as one of my two Books We Loved selections for April (I will feature the other selection next week). As Hartov explains in the written Q&A below, his novel, released just this past Tuesday, explores the little-known phenomenon of soldiers with mixed Jewish heritage who fought for the Third Reich.

But I will let him explain the details. My thanks go to the Publicity Department at Hanover Square Press for both the book, intended for a New Books in Historical Fiction podcast I couldn’t fit into my schedule, and the Q&A. I would have sent Steven Hartov questions myself, but they would have been the same questions, so why force him to type out the answers twice?

What is your new novel, The Soul of a Thief, about?The Soul of a Thief is an adventure, a war story, a romance, and a coming-of-age novel—all set during the year of the Allied invasion of Europe during World War II. The story centers around a nineteen-year old Austrian boy of partial Jewish heritage, Shtefan Brandt, who finds himself as the adjutant to a colonel in the Waffen SS, Erich Himmel, and must not only protect his potentially mortal secret but survive the horrors of combat. To add to his conundrum, our young hero also falls in love with Colonel Himmel’s young French mistress, Gabrielle Belmont, who is also of “questionable” heritage. When Shtefan discovers that Himmel intends to escape from Germany’s inevitable defeat and enrich himself by robbing an Allied paymaster train, the boy plots to betray the colonel by stealing both his mistress and his fortune.

Where did the inspiration for the novel come from?Much of the inspiration for the story came from my own background, as my mother and her family were all Austrians, some of whom, although Jewish or partially Jewish, served in the Austrian or German armies. However, the driving force behind the novel came from a recurring dream that I used to have as a child; it is a scene that figures prominently in the book.

Who were the Mischlinge? Why has their story rarely been told?The Mischlinge were Germans or Austrians of “mixed” heritage, meaning that somewhere in their ancestral backgrounds persons of Jewish faith had married into the family. During the Nazi era, German and Austrian citizens had to prove their “racial purity,” and Mischlinge were considered to be Jews and persecuted as such. However, exceptions were made in accordance with the requirements of the Nazi war machine, and many such persons were allowed to serve. For those who survived, such service was regarded as shameful, which is why very few of them have spoken out about their wartime experiences.

Are any of the characters in the novel, in particular Shtefan or Colonel Himmel, based on real-life people or did you create them from whole cloth for the novel?Shtefan is based, in part, on my great-uncle Alexander, who served in the German Luftwaffe until he was discovered to be a Mischling and sent to a concentration camp. Colonel Himmel is based on a figure who used to appear in a recurring childhood dream; I do not know his origin. Many of the other characters are compilations of soldiers I have known personally, of various nationalities (soldiers are very much the same, everywhere). Gabrielle is based on a long-lost love.

You have a strong military background, and there are aspects of The Soul of a Thief that tap into your knowledge. Would you classify the story as a war story first and foremost?I would not classify the novel so much as a war story, but rather as a story that takes place during a war. I view it more as a coming-of-age adventure with a powerful romantic essence.

And perhaps that’s why I liked it so much, even though war is really not my usual cup of tea! Thank you again, to Steven Hartov and his publisher, for this opportunity to travel a fictional path I normally would not take.

Steven Hartov, a former member of the US Merchant Marine Military Sealift Command and the Israel Defense Forces Airborne Corps, is the author of, among other works, a series of espionage novels nominated for the National Book Awards—The Heat of Ramadan, The Nylon Hand of God, and The Devil’s Shepherd. He also writes screenplays and nonfiction.

Hanover Square Press, an imprint of HarperCollins, published his The Soul of a Thief on April 17, 2018. Find out more about him at http://www.stevenhartov.com.

Published on April 20, 2018 06:00

April 13, 2018

Binge-Watching Muscovy

I’ve mentioned before that Pinterest is my favorite among the social media sites, for several reasons. First, I’m an intensely visual person and thus an intensely visual writer. To “get” directions I have to see the map in my head, and to “get” my characters I must see them too, preferably on screen as I’m writing. So the first thing I do when starting a new story is to collect images of my characters and settings, which I update as needed as my sense of them strengthens.

I’ve mentioned before that Pinterest is my favorite among the social media sites, for several reasons. First, I’m an intensely visual person and thus an intensely visual writer. To “get” directions I have to see the map in my head, and to “get” my characters I must see them too, preferably on screen as I’m writing. So the first thing I do when starting a new story is to collect images of my characters and settings, which I update as needed as my sense of them strengthens.Second, I write about a time and places that are almost entirely unfamiliar to my American and West European readers. I would love someday to see my Legends and Songs novels translated into Russian, where the cultural context even five hundred years after the fact is so much more familiar. But until that happens, my Pinterest boards are the best way to find ideas for myself and convey a sense of the world I have adopted as my own to others.

So you can imagine how delighted I was when images from a Russian television series about Sophia Palaiologina—the niece of the last Byzantine emperor and the wife of Ivan III “the Great” of Russia, thus the grandmother of Ivan IV “the Terrible”—began showing up on my Pinterest feed. I suppose even then I could have gone to YouTube to look for it—although it’s a commercial production, so I might not have found it. But I didn’t: much as I love Russian history, especially medieval Russian history, and despite decades of speaking and reading Russian, I have to admit that in my down time I want to watch movies and TV in English.

Then Sophia showed up at Amazon.com. The episode summaries must have been translated by Google, for they are hilarious, but the subtitles are pretty accurate. The actors are true to type, their performances excellent, the settings and costumes are perfect, and the whole first season is riveting historical fiction. Think the BBC’s Victoria, but with way more furs, poison, and treachery.

Look at this wedding ceremony, for example: can’t you just see Daniil and Nasan or Alexei and Maria in this setting?

I was hooked. Right now, Season 1 is still available for free on Amazon Prime, but I shelled out $12.99 (total) for the first eight episodes so that I could continue watching even if it disappears from the free collection, as things tend to do on Amazon Prime. As I said, I’m hooked. I watched the full set in three days, and I can’t wait for Season 2.

Note that I also said riveting historical fiction. Alas, considerable liberties have been taken with basic plot points. The Muscovites were, so far as we know, not resistant, as they are depicted here, but delighted to have scored a dynastic connection with the emperor of Constantinople, whose defeat by the Ottoman army had left Muscovy (at least in the minds of its own rulers and government) as the last bastion of Orthodox Christianity in a troubled world. Which is not to say that they expressed this realization in the “Moscow as Third Rome” phrasing that opens the series, but the realization itself does seem to have existed. I could go on, but you get the point.

So don’t treat it as a televised history lesson, except in the sense that the general depiction of the place and its court are accurate. (Hint: Victoria is not 100% historically accurate either.) What we do have is a full cast of delightfully fictional characters: the strong-willed bride, her wiser but still somewhat impetuous husband, his determined but not unkind mother, enemies of various sorts (modern-day Russian nationalism especially affects the portrayal of the enemies—Tatars [pictured here], Novgorodians, Lithuanians—so take these portrayals in particular with a large grain of salt), the naive but charming husband and the treacherous daughter-in-law, and a whole host of scheming Italians and boyars. It’s tremendous fun, and if you ever wanted to get past imagining the world I portray in my Legends novels and actually see how it looked, this is the perfect place to start.

So don’t treat it as a televised history lesson, except in the sense that the general depiction of the place and its court are accurate. (Hint: Victoria is not 100% historically accurate either.) What we do have is a full cast of delightfully fictional characters: the strong-willed bride, her wiser but still somewhat impetuous husband, his determined but not unkind mother, enemies of various sorts (modern-day Russian nationalism especially affects the portrayal of the enemies—Tatars [pictured here], Novgorodians, Lithuanians—so take these portrayals in particular with a large grain of salt), the naive but charming husband and the treacherous daughter-in-law, and a whole host of scheming Italians and boyars. It’s tremendous fun, and if you ever wanted to get past imagining the world I portray in my Legends novels and actually see how it looked, this is the perfect place to start.And if you do get hooked and need more binge-watching material before the 2018 season arrives, try Ekaterina: The Rise of Catherine the Great . It has two seasons available, with twenty-two episodes. It’s even more fictional than Sophia, not least because I think it draws heavily on Catherine’s own memoirs, which are self-serving in the extreme, as well as most of the extensive scuttlebutt that surrounded Catherine’s rise to power and reign, much of it disseminated by her far-from-loving son. But if you don’t take these series too seriously, they will certainly entertain!

Images: Screen captures from Sophia.

Published on April 13, 2018 08:09

April 6, 2018

Writing the War

As should be clear if you have listened to my interviews for New Books in Historical Fiction, people come to fiction writing by many different paths. Most of us start out with a love of reading; some begin penning stories as children; others—including me—have always considered ourselves writers but never intended to extend our repertoire beyond nonfiction until that one inescapable tale forced itself into our consciousness demanding to be told.

As should be clear if you have listened to my interviews for New Books in Historical Fiction, people come to fiction writing by many different paths. Most of us start out with a love of reading; some begin penning stories as children; others—including me—have always considered ourselves writers but never intended to extend our repertoire beyond nonfiction until that one inescapable tale forced itself into our consciousness demanding to be told. In the case of John Richard Bell, my most recent interview guest, the impetus came from family stories, told and retold for decades, and the push to write them down before they vanished into history with the father-in-law who had lived them. As Bell explains in the interview, his self-reeducation from CEO to novelist took a long time, not only to learn the ropes of writing a novel but to trim and fine-tune that original draft into a taut and compelling story that honors the essence of those family tales while conveying, through a set of fictional characters and events, the larger themes of a little-known aspect of a very well-known conflict: World War II.

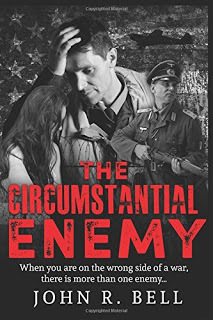

Much of the cutting and fine-tuning was painful, as it always is for writers forced to jettison their cherished prose. But the result makes the pain worthwhile, because The Circumstantial Enemy does not only reveal the effects of the war on Croatia, including its contributions to the rise of Josip Broz Tito and the postwar unification of the no longer unified Yugoslavia. It also confronts a powerful but—in fiction, at least—often disregarded truth: that fighters, whether on our own side or the enemy’s, are not necessarily zealots for the cause. Sometimes, indeed, they end up on one side or the other because circumstances put them in the wrong place at the wrong time.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction:

We all imagine that, when put to the test, we will end up on the right side of history, however we define it. Nowhere is that statement more true than in reference to World War II. But sometimes people end up on the wrong side for reasons outside their control—even on a side they don’t believe in. Such is the fate that confronts Tony Babic, the hero of John Richard Bell’s debut novel, The Circumstantial Enemy , based on the true story of his father-in-law’s life during the war.

Tony, when we meet him, is a young pilot flying for the Croatian Air Force. His experience of causing one death and witnessing another—that of his commander—has left him eager to find a more peaceful way to exercise his talents. But his country, in an effort to escape both Serbian control and Nazi conquest, has chosen to ally with Germany in return for nominal independence as a puppet state. Tony has little choice but to fly for the Luftwaffe and is soon taking part in the Siege of Leningrad. Meanwhile, his best friend and the woman they both love (the daughter of Tony’s dead commander) become ever more deeply involved in a different epic battle: Josip Broz Tito’s campaign to unify all the Southern Slavic states under a single communist banner.

Tony eventually escapes his service to the Germans only to fall into the hands of the Americans. Soon he’s on his way to a POW camp in Illinois. But circumstances conspire to make him an enemy even there, not least in the eyes of the people he has left behind.

Published on April 06, 2018 06:42

March 30, 2018

Juggling Books

Normally, when I have a writing vacation as I did this week, I write. In a perfect world that’s all I do for the entire nine (or however many) days—with breaks for eating, sleeping, and family, of course. I even try to schedule my podcast so that neither questions for the authors nor the interviews themselves intervene.

Normally, when I have a writing vacation as I did this week, I write. In a perfect world that’s all I do for the entire nine (or however many) days—with breaks for eating, sleeping, and family, of course. I even try to schedule my podcast so that neither questions for the authors nor the interviews themselves intervene.But this time is different. For one thing, I have two novels on the brink of completion: The Shattered Drum , already critiqued and revised; and Song of the Siren, which has passed one beta reader and is waiting for comments from another before proceeding to final draft status. Second, I have two other Five Directions Press novels in the final stages of typesetting and proofing: Gabrielle Mathieu’s The Falcon Soars , which concludes her excellent Falcon trilogy; and Joan Schweighardt’s Before We Died, which kicks off a new trilogy, Rivers. In Before We Died, the river in question is the Amazon, circa 1910.

The publication schedule is The Falcon Soars (May), The Shattered Drum (July), and Before We Died (September). Song of the Siren won’t appear until early 2019, when it too will signal the beginning of a new series, Songs of Steppe and Forest. I already have rough ideas for three more books in that series—Song of the Shaman, Song of the Sisters, and Song of the Storyteller—but I can keep only so many plots and main characters in my head at one time. With The Shattered Drum and Song of the Siren, I’m already at capacity. So Grusha and Nasan must wait their turn.

As a result, this writing vacation has been devoted to other things: basic appointments that are hard to schedule around work (things like haircuts and annual physicals); proofing The Falcon Soars; editing my next New Books in Historical Fiction interview (yes, I’m actually making progress with Audacity, although I could write a whole blog post there); reading for the interview after that; typesetting and checking The Shattered Drum; updating the Five Directions Press site; writing a couple of blog posts; and considering where to go next.

One plan is to make some minor revisions to The Golden Lynx so as to post a newer edition that I can sell through Ingram Spark as well as CreateSpace/Amazon. That’s because I have reason to think that some of my colleagues have begun to adopt the book for courses in women’s history or Russian history, which would be great. A second project is to take that revised version and combine it with The Winged Horse and The Swan Princess in an electronic boxed set, so that people (at least people with Kindles or Kindle apps) who discover the series close to its end can catch up quickly. A third, once it gets that far, involves typesetting Song of the Siren. And of course, I still have to finish Before We Died, which is due long before its September release because it’s heading for a proper publicity campaign.

But by the end of summer at the latest, I expect to be writing again. And then my writing vacations will be just that, complete with virtual beach umbrellas and cocktails by the pool.

Image: Clipart.com no. 109717486.

Published on March 30, 2018 06:00

March 23, 2018

The Perils of Podcasting

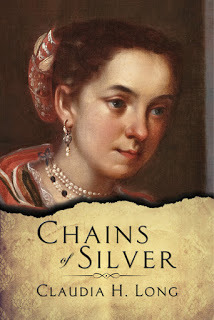

As I promised back in February 2017, when I welcomed Claudia H. Long as our newest member of Five Directions Press, our group has just published the third in her Tendrils of the Inquisition series,

Chains of Silver

. So it seemed like the right time to interview her for New Books in Historical Fiction. That, through no fault of NBHF’s or mine (four nor’easters in a row, with accompanying power and Internet outages, bear most of the responsibility), I have so far managed exactly one interview this year just added to the pleasure of the interview.

As I promised back in February 2017, when I welcomed Claudia H. Long as our newest member of Five Directions Press, our group has just published the third in her Tendrils of the Inquisition series,

Chains of Silver

. So it seemed like the right time to interview her for New Books in Historical Fiction. That, through no fault of NBHF’s or mine (four nor’easters in a row, with accompanying power and Internet outages, bear most of the responsibility), I have so far managed exactly one interview this year just added to the pleasure of the interview.Alas, my older cat—often featured on this blog and currently shedding like a maniac due to the shifting weather patterns—enlivened the interview not only with his usual yowls announcing his imminent arrival but also by hacking into the microphone throughout one entire answer. Then, when he calmed down after a return downstairs and yet another series of announcement yowls, he expressed his bliss by purring steadily. So I got to spend half of Saturday trying to follow opaque online instructions for Audacity until I finally figured out how to silence the hacking sounds and at least three-quarters of the meows. The joys of podcasting and pet ownership, amplified on this occasion by the knowledge that the cat could just as easily have stayed in Sir Percy’s office.

And no, if you’ve ever lived with a cat, especially a Siamese cat, the solution is not to shut him out. First off, I have a loft office without a door, and second, if I did have a door, I know better than to shut it with the cat on the other side. Announcement yowls don’t begin to match dismayed rejection yowls in volume or intensity.

But yowling animal aside, the interview went well, Claudia was wonderful, and most of the distractions have since been scrubbed from the file. Meanwhile, I have (fingers crossed) another interview tomorrow, a third in early April, and a fourth scheduled for the first or second week in May. Surely by then the nor’easters will have stopped.

So listen to the interview, and if you hear a stray yowl or an odd hum, don’t worry: that’s just purring. Meanwhile, please like the NB Historical Fiction, NB Literature, NB Fantasy, and New Books Network pages on Facebook, together with the pages for any other channels that appeal to you, and share our posts when they go up. (If you’d like my author page, that would help too.) The change in Facebook algorithms has made it more difficult to get the word out even to people who want to receive it, and the ongoing scandals are likely only to make the situation worse. We are not Russian bots, and we don’t collect or save your data; on the contrary, we provide a genuinely free public education service. So please let your friends know that we exist. The more listeners we have, the better our chances of attracting funding that will keep the network on the air.

As always, the rest of this post comes from New Books in Historical Fiction.

From the fifteenth through the early eighteenth centuries, the Catholic authorities in Spain and its colonies, including Mexico, took a hard line against the Jewish community. Those who would not convert were banished or killed; officially the community did not exist. But in fact, many conversos, as these forced Christians were called, continued to practice their ancient faith in secret. This historical tension between past and prudence forms the background of Claudia H. Long’s Tendrils of the Inquisition series, especially the most recent novel, Chains of Silver (Five Directions Press, 2018).

Marcela Leon belongs to one such Crypto-Jewish family. At fourteen, she sees her parents and grandfather dragged off to face the last gasp of the Inquisition in Mexico. Her relatives survive, but at great cost to their dignity and their fortune. To protect Marcela, her family sends her first to a nearby hacienda, then north into exile, where she becomes the housekeeper to a Catholic priest who sympathizes with her plight but is determined to force her into compliance, including what he perceives as her religious deviance. Through his efforts and those of her wealthy uncle, who lives in the same town, Marcela adjusts to her new situation—until a series of crises force her to reconsider both her heritage and the source of her mother’s strength.

Published on March 23, 2018 06:00

March 16, 2018

Love on Four Paws

“It began, this journey of many lifetimes, in an ordinary way: he and I went to pick oysters on the shore. He loved them more than any other food, loved the ritual of unlocking abrasive shells to discover a treasured interior, smooth alabaster and incorporeal liquor. And when he feasted on them, they had a transformative effect: his shoulders dropped, his brow unknotted, and his eyes softened, sometimes to tears.”

“It began, this journey of many lifetimes, in an ordinary way: he and I went to pick oysters on the shore. He loved them more than any other food, loved the ritual of unlocking abrasive shells to discover a treasured interior, smooth alabaster and incorporeal liquor. And when he feasted on them, they had a transformative effect: his shoulders dropped, his brow unknotted, and his eyes softened, sometimes to tears.”So begins, too, Damien Dibben’s new novel, Tomorrow . A novel with two prologues, set five years apart, and narrated by a dog. A dog who, as you can see from the above, has a clear vision and an astonishing vocabulary, who has lived for centuries and acquired considerable wisdom and perspective yet remains a hound waiting patiently for his master’s return—for 127 years.

It shouldn’t work, but it does, beautifully. The dog, who until the end we know only by the names his master bestows on him—“my champion,” most often—may grow wiser and develop insight on the oddities of the human species, but he doesn’t cease to be a dog. Odors fascinate him, and he identifies people and other animals by them. He defends his food and space from other dogs. He helps those of his own kind abandoned by their human companions, whether through death or departure, involuntary or—in the case of the delightful Sporco, another dog who insists on joining the narrator’s pack—deliberate. He loves his absent master unconditionally. He delights in and then grieves the loss of Blaise, the female dog who, not being immortal as he is, can spend only a short number of years as his companion. It never occurs to him, until his master briefly returns only to vanish once more, to leave his post. He is loyal and true, like the best canine companions. More than anything else, he is unwavering.

And as you can see from the opening, the writing is gorgeous. Dibben, the author of the YA series The History Keepers, excels in this haunting novel. A pair of alchemists, linked in ways that become clear only near the end, enter into conflict over the refusal of one to save the love of the other by conferring immortality on the lover as well as his own dog. The antagonist, shocked at this refusal, vows to exact a price. The dog senses the danger, but he can’t understand the tortured logic that drives his master’s foe. And when the antagonist’s revenge plays out, the dog, like all dogs, realizes only slowly what has happened. As he progresses from Elsinore in 1602 to the battlefield of Waterloo more than two centuries later, he offers a distinctive perspective on our early modern past—and our present.

I wish I could fit this author into my podcast schedule, but the book releases next week, and I have three interviews in line to close the gap inadvertently opened from mid-January to now for a variety of reasons ranging from stage fright (not mine) to the nor’easter that blew out my power and Internet connection for four days straight. So for the moment, this blog post is the best I can do. But I see that Dibben has another adult novel in the works called The Colorist, set in Renaissance Venice and exploring the vast lengths to which painters would go to secure new shades. So I hope to have another chance for an interview when that book comes out. And if I do, you can bet I’ll also be asking him about Tomorrow.

Because who can resist an immortal dog?

Published on March 16, 2018 14:29

March 9, 2018

Bookshelf, March 2018

Between the double-barreled nor’easter that knocked out my power last Friday and my Internet and cable connections for the entire weekend (so much for the Oscars) and general overwork, I haven’t spent much time on social media recently—even to alert people to last week’s blog post. I had to reschedule my planned New Books in Historical Fiction (NBHF) interview with John Bell, so I don’t have that to post about, and while a lot of books have come my way, I’ve had little time to read them due to evenings spent going through Song of the Siren and The Shattered Drum. So with heat, light, and Internet restored—at least until the next storm blows through—it seems like the perfect time for a bookshelf post. Here, more or less in order, are a few of the titles on my short list (I have at least twice as many contenders waiting in the wings for a future post).

John Richard Bell, The Circumstantial Enemy (Endeavour Books, 2017)

Technically, I’ve read this one, but until I complete the interview with the author, it’s still front and center in my brain. Tony Babic, a twenty-year-old Croatian pilot whose main goal in life is to get out of the air force after witnessing a tragic accident, is instead pressed into flying for the Luftwaffe against the USSR. Meanwhile, his close friend and the woman they both love become caught up in Tito’s drive to unite Yugoslavia under the communist flag. After a series of adventures, Tony ends up in a US POW camp for German and German-allied prisoners. A very different but equally engrossing take on the Second World War from that adopted by Gwen C. Katz in Among the Red Stars, the subject of my previous NBHF interview.

Claudia H. Long, Chains of Silver (Five Directions Press, 2018)

Since I edited and typeset this book for my own writers’ coop, Five Directions Press, technically I’ve read it too, even though its formal release date is next Thursday, March 15. But my interview with this author, which was supposed to follow the one with John Bell and will now precede it due to the vagaries of weather and electricity, is also still in play; in fact, I need to revisit the book to draw up draft questions this weekend.

Like two of Claudia Long’s previous novels, Josefina’s Sin and The Duel for Consuelo, this story takes place in colonial Mexico—here among the hidden Jewish community, under pressure from the Catholic Church during the last days of the Inquisition. Marcela Leon, sent to Consuelo’s hacienda for protection after her own parents’ arrest, finds it difficult to understand the danger that faces her. Marcela is, after all, only fourteen years old. Her fiery personality and teenage indiscretion lead to her exile as a housekeeper to a priest in the northern mining region of Zacatecas, where she grows up to become one of the town’s wealthiest and most powerful citizens. But it takes a series of family tragedies before Marcela truly understands the secret of how her parents, especially her mother, endured persecution and finds the strength to make peace with her past.

Damian Dibben, Tomorrow (Hanover Square Press, 2018)

One of the publicists with whom I’ve worked on setting up interviews sent me this novel unsolicited, and I immediately fell in love with the concept. A dog, known only as “my champion” or “my hero” and from the cover picture a chocolate Labrador (although dog breeds are in fact a later development), lives with his master, an alchemist, in Denmark in 1602. Somehow the dog becomes immortal, as his master and his master’s antagonist also are, but he winds up alone. Like the faithful hound he is, he travels all over Europe for the next two centuries, visiting the canals and palaces of Venice, the court of Louis XIV at Versailles, the battlefields of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, and more. Along the way, he acquires a certain canine wisdom. I’m only about fifty pages in, so I don’t know how the story will develop, but the writing sparkles and the idea is simply irresistible. More about this one in next week’s post. The book is due out March 20.

Adrienne Sharp, The Magnificent Esme Wells (Harper, 2018)

Another novel, this time solicited, from one of the publicists I’ve contacted for NBHF interviews. I’m currently about halfway through and loving this author’s previous book, The True Memoirs of Little K (2010), about the life of the prima ballerina assoluta Mathilde Kschessinska and her (heavily fictionalized—the title is a joke) prolonged affair with the last Russian emperor, Nicholas II. The Magnificent Esme Wells takes place in Hollywood and Las Vegas during the days of Bugsy Siegel. Esme’s mother is a showgirl in the movies, her father a gangster, but they both dream of making it big in their respective realms. In the middle is Esme, trying to make sense of it all.

Due for release in early April, this book will be the subject of a future NBHF interview. In the meantime, don’t miss the earlier novel, especially if you're a ballet fan or a Russia fan. Mathilde spends most of her time plotting how to get back in the tsar’s good graces and defeat her self-perceived rival, Empress Alexandra (Alix), so you need not be a ballet fan to love the book. But if you are a fan of the Russian Imperial Ballet and enjoy reading about strong-minded women bent on pursuing their interests and defending their children, you absolutely must seek out this book. Besides, is that cover not reason enough to justify purchasing the book?

Published on March 09, 2018 10:13

March 2, 2018

Home, Sweet Home

There are many things I like about working from home. The commute is great, even in the depths of winter. The wardrobe includes whatever I feel like throwing one—ancient blue jeans, thirty-year-old sweaters, tank tops in summer, the works. Lunch, although not quite free, costs less than the most basic cafeteria. I can fit short ballet barre workouts into my lunch break. The only restriction on my coffee consumption is common sense. And that enormous time waster—meetings—rarely clutters up my day, although e-mail, my primary means of communication with the outside world, does its best to slurp up every available moment.

But as I discovered last Friday, there is one big drawback to working from home. When the heat goes out, there’s no central plant to call. For the last week Sir Percy and I have dodged daily visits by earnest technicians bent on taking our ancient boiler apart and putting it together again while wrestling the cats for access to the space heaters that provide our only source of warm air.

So far, the cats have won. They didn’t put us in this position, after all; we did it, however inadvertently, to them. One cat—the elder statesman depicted above—has developed an entire philosophy of space heaters. He follows them around the house, listening for the fans and when they go on and off. Early in the morning, he doubles up, positioning himself under the overhang of quilts at the end of the bed so he can soak up heat from the bedroom heater while sheltered under layers of fabric. In the evenings he gloms onto the person with the Snugli, then moves to the back room once that heats up.

I can only hope that the situation resolves itself soon: that the next earnest technician, due any moment, installs the crucial part that will restore the boiler to functionality—not forever, because it’s reached the end of its natural life and must be replaced before fall sets in, but for a few more weeks while we figure out how to finance the new one.

But I do know that whether today proves to be the deciding moment or not, the cats are prepared.

Published on March 02, 2018 06:00

February 23, 2018

Judging a Book by Its Cover

A short post this week, because I’ve been writing like mad on the first novel in my new series while juggling my regular job and a freelance project that, although no doubt worthy and often interesting, seldom rises to the level of scintillating writing. Don’t get me started on tax season, which I have spent the last few weeks denying, even though I know I need to buckle down to 1099s, W-2s, and all those work expenses that require categorization and totaling.

A short post this week, because I’ve been writing like mad on the first novel in my new series while juggling my regular job and a freelance project that, although no doubt worthy and often interesting, seldom rises to the level of scintillating writing. Don’t get me started on tax season, which I have spent the last few weeks denying, even though I know I need to buckle down to 1099s, W-2s, and all those work expenses that require categorization and totaling.An article dropped into my in box today that gave me pause: an interview with three independent publicists, it included lots of information about rates (high) and dedication (also high) and numbers of clients served (surprisingly low), as well as some tips for those of us who can’t afford the high rates.

All good, of course, but the article seems to take one crucial point for granted: before you hire a publicist, you need a professional product to sell.

Specifically, you need a great cover, a properly formatted text (print or e-book), and most of all, stellar prose. I can’t tell you how many pitches I get from publicists for New Books in Historical Fiction for books where the cover looks like something drawn by a middle-schooler, the fonts are small and bland, the book description goes on for pages without ever capturing the story, and the writing—assuming I get far enough to research the book online—is as flat as the proverbial pancake. It may sound mean, but these are not authors I want to interview. They shouldn’t sink their funds in publicity but use them to hire a writing coach and a competent book/cover designer.

Because this is a short post, I won’t go into the specifics of what makes a professional cover design. You can find out more, if you’re interested, in JD Smith’s

The Importance of Book Cover Design and Formatting

(you can also hire JD Smith herself, if she has the time, to produce a cover for you—check out her portfolio).

Because this is a short post, I won’t go into the specifics of what makes a professional cover design. You can find out more, if you’re interested, in JD Smith’s

The Importance of Book Cover Design and Formatting

(you can also hire JD Smith herself, if she has the time, to produce a cover for you—check out her portfolio). If she’s too busy or her work is not to your taste, there are many other gifted cover designers out there. You can team up with writers who have the design skills you lack: here at Five Directions Press we have our own cover designer, who is building her portfolio with the occasional freelance job, as well as professional editors, book designers, and typesetters.

You can also work with a subsidy publisher: She Writes Press selects books for high-quality writing, then contracts for editorial services as well as cover design and typesetting, yielding appealing and well-written novels with minimal errors. Book production companies like Bookbaby include cover design in their packages.

Or you can hire a graphic designer who specializes in book covers. In addition to searching the Internet in the usual way or posting requests for recommendations on social media, one place to check is Reedsy.com, which vets editors and cover designers, with whom you can then contract on a one-on-one basis.

In all these cases you should check the output online to be sure you like the style before you commit yourself to spending several hundred dollars. But unless you know what you’re doing, don’t use free software offered online, including the “cover creators” offered by the various online booksellers. Be wary of sites that advertise book covers on the cheap. Don’t use your own artwork. Don’t design your book or your cover in a word-processing program. And don’t assume your book will sell itself.

To stand out in a crowded market, you need a great cover, a great book description, and most of all, a great book. Even with those three things, your book sales will probably fall far below your hopes; it’s the nature of today’s market. But without those three things, there’s no point in spending a small fortune on a publicist, because the best publicist in the world can’t compensate for the fact that we all judge a book by its cover.

Images sprinkled throughout this post represent good cover design independent sources. No cover appeals to everyone, but each of these examples includes an image that captures the story and the genre of the novel, fonts used creatively and well, and respect for proportions and alignment.

Images sprinkled throughout this post represent good cover design independent sources. No cover appeals to everyone, but each of these examples includes an image that captures the story and the genre of the novel, fonts used creatively and well, and respect for proportions and alignment.

Published on February 23, 2018 06:00

February 16, 2018

Oh, Those Names!

One of the more annoying habits of our ancestors, from the perspective of a historical novelist, is their lamentable lack of imagination when it came to naming their children. This complaint applies particularly, but of course not exclusively, to the Russian nobility and the Russian royal family between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries.

This apparent lack of imagination had several causes. Russians celebrated name days rather than birthdays, but it was not uncommon to name a child after the saint on whose day he or she was born, so that the two coincided. The more days in the calendar associated with Johns, Marys, or Gregorys, the more children carried those names. Saints could also rise and fall in popularity, so one can trace the growing cult of SS Boris and Gleb, for example, by the increased prevalence of those names among the population.

Another issue was family commemoration: entire clans had series of children named Nikolai or Boris or Anna or whatever after parents and dead grandparents and other relatives. Some families even gave two brothers or sisters the same names, confusing the picture mightily and forcing everyone else to distinguish between Ivan Petrovich the Elder and Ivan Petrovich the Younger. But even beyond that, there seems to have been a strong preference for certain names in the sixteenth-century Russian aristocracy. Ivan, Vasily, Fyodor, Dmitry, and Yuri—all names favored by the royal family—were often encountered among noble boys, whereas a lot of girls went by Anna, Elena, Anastasia, or Maria.

All this creates difficulty for a novelist trying to maintain some historical veracity. I managed to juggle the issue all through the Legends novels by focusing as much as possible on my own invented characters, whom I did my best to ensure had not just unique names but one form of their unique names (another problem with Russian custom that I’ll discuss someday). For the most part that worked, despite the pair of Yuris (uncle and nephew), the double Sigismunds (father and son), and more Vasilys and Ivans than one could shake a proverbial stick at.

But midway through my current work in progress, Song of the Siren, I ran smack into a dilemma. Bad enough that in 1542, when that novel is set, the Poles, who were in dynastic alliance with the Lithuanians, had two kings/grand dukes simultaneously named Sigismund—called Sigismund the Old (father) and Sigismund Augustus (son) to keep them straight. The Russians did them one better: then in a kind of political meltdown, they had become enmeshed in a conflict that I could explain only by citing the rival claims of three princes named Ivan. You can imagine the conversation from a poor reader’s perspective: Prince Ivan is fighting Prince Ivan for control of Prince Ivan. Huh?

I wrote it out, complete with a slap from my Polish character about the Russians’ not knowing any other names, unconcerned by his own people doing the exact same thing. Nope. Didn’t work. By the end of the conversation even I was confused, and I actually know a fair bit about the history involved. The other writers in my critique group were scratching their heads, and I didn’t blame them. I needed another solution.

As I’ve said before, I’m a historian first and foremost; the novels are fun, and I love writing them, but even if I can’t claim perfect accuracy—not least because our forebears tended not to leave detailed records of what went on in their heads at any given moment, any more than we do—I have mostly avoided changing the names of people who once actually lived and walked the earth. I grumbled and groaned and tried different tactics, but in the end I realized I had no choice: two of the Ivans would have to receive different names.

And so it is. In the historical note, I explain who they really were. And in fact, given how little we know about any of these historical figures, in some ways I find it works better to change their names, because now they are “mine,” in a way they were not before, and I don’t need to worry about someone noting I have them strutting around in the palace in Moscow when they were really besieging Kazan or some such thing. They can do and say and be whatever the story requires, beyond the broad strokes of the conflict that forms the backdrop to the novel.

Still, I must admit that I have acquired a whole new appreciation of diverse naming practices. They make a novelist’s life so much easier....

Image: Konstantin Makovsky, The Kissing Custom (1895). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. What are the chances that every guy lounging at the table is named Ivan?

Published on February 16, 2018 06:00