Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 541

April 24, 2012

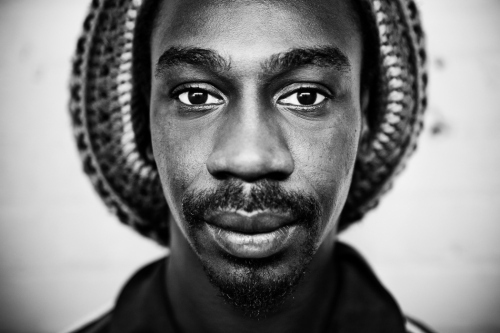

Photographer Gregory Chris: Shooting Nneka, Meta and Just a Band

A few weeks ago I sent an email to established French photographer Gregory Chris (see his website) and asked him about featuring his photographs of African music stars on AIAC. He kindly obliged and also responded to questions. Photographer Gregory Chris shot African music stars Nneka, Meta (of Meta and the Cornerstones) and Just a Band in and around New York City. “I wanted to shoot the artists in the streets of the city, in the neighborhoods where they live, their favorite places, inside their homes, in a place they feel comfortable. Basically, I wanted to shoot them as they are.” The photographs were made a few months ago while he was spending time in New York City. A South African magazine, One Small Seed, had asked him to do something for them and he decided on making photographs of “African artists living in New York City.” Below we feature some of the photographs and Gregory’s descriptions of how he came to shoot the specific artists, what he tried to convey. First up is Nneka.

Gregory Chris:

For Nneka, the only opportunity I had to get pictures of her, was before her concert at SOB’s. I went there with my assistant and with Ginny who work at Okayplayer.com. I did not really know what to expect, didn’t know how much time I had and when I would be able to do the pictures. It was a long wait, other photographers were there to. Then suddenly it happened. Someone came to fetch us and we went down to the artist lounge. Another photographer went first, so I realized it would be a new experience for me and that I would not have much time and not much choice where to take the photographs. My turn came. I introduced myself to Nneka who it seems was focusing on getting ready for her show. I told her that my assistant and I were from France, from Paris. I looked around while talking to her and I noticed this tiny red room with a big make-up table with a mirror and nobody inside. I asked Nneka to follow me into this room, put a high chair for her to sit on. And with the only light of the mirror and my assistant with a reflector, I started to take pictures. Trying to see how she was feeling, her mood, talking about Paris, and about her being there etcetera. We had about 10 minutes. But it has been a great moment almost out of time.

That night I went to photograph Nneka I also met Meta. I had been listening to Meta’s music for six months — a friend of mind that came to live in New York City introduced me to his music. I was coming back from South Africa and my friend posted Meta’s video “Somewhere in Africa” on Facebook. Of course it talked to me and I bought the album on iTunes. What I didn’t know was the story behind it. So when I met Meta I told him about this. Then a few days later I told my friend, ‘I met Meta and I going to do his portrait,’ and she told me how she knew his music: One day she called me on Skype because she couldn’t deal with the windows of her apartment (American windows opening by sliding up and down, we don’t use this in Europe). So I tried to help but the window was blocked. She knocked at her neighbor’s door for help and it was Meta. He was listening to his music loudly so he thought that was the reason for my friend’s visit. But she says, no I like your music! He finally solved her window problem and offered her the CD and after that she realized he was the singer. Life is a small world.

The day I was shooting Meta, I met him at his place and told him the whole story — and he remembered it (my friend’s a remarkable woman, and she speaks French as Meta does). So suddenly I was not only a photographer coming to shoot him…and we started from there. I wanted to shoot him on his apartment so we begin there and once in the corridor he told me that’s the apartment where your friend used to live. I didn’t prepare much. I didn’t know the place but I adapted to the situation, location, light, weather etc . I like natural and continuous light and most of the time my assistant fills it with a reflector. When Meta told me we could get to the roof I said let’s go for it. Shooting on a rooftop in Brooklyn with the view of Manhattan is great. But it was on his way back to his apartment, in the corridor, that I notice these neon lights and suggested to do one more. By then he was more relaxed, I did a couple of shots and they are my favorite pictures of him … right in front of the door where my friend used to live.

Just a Band I met on my second trip to New York City. The first time I had an appointment with them, early evening in Brooklyn at a place artists come to record. I met only two of the three band members and did a couple of shots but the light, the time, was not exactly right inside and it was night outside. I managed to get something that night but I also got to meet them again, the three of them, and to do a shoot in the street of Brooklyn where they were staying. They don’t live in NY, but were there for a couple of weeks. So I met them and we went for a walk in the streets trying to find interesting locations. When I found the place with the grilling (wire-netting) I liked it…I like to have some out of focus things in front of my camera. I wondered at the time whether it wasn’t too much “cliché”, but I liked the effect and the message that can be in it.

* Also see Gregory’s photographs of an orphanage in Nyanga, Cape Town on his website.

April 23, 2012

The Strategic Kinship of Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto

We survived Kenyatta / We survived Moi / We might survive Kibaki / Will we survive ourselves? (Anonymous)

The Kenyan politicians Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto have never been closer. Although they are facing charges at the International Criminal Court (ICC), the two have been busy convening prayer-cum-political rallies across the country in their campaign for the presidency. At almost every rally Uhuru and Ruto have knelt on the dais, been anointed with oil and prayed for, and they’ve delivered campaign speeches that double as sermons about their persecution and martyrdom at the hands of the ICC.At these rallies they have bandied the slogan “tuko pamoja”, Swahili for “we’re united”. For Uhuru and Ruto, who are from different ethnic communities, “tuko pamoja” registers a political legacy based on fictive but nonetheless strategic kinship. Presidential candidates in Kenya are not hard pressed to run for office on the basis of their policies. Sweeping slogans often take the place of policy (in 2002 it was “Kibaki Tosha” — “Kibaki is more than enough”). Creating voting blocs through ethnic alliances during election years is still the order of the day, so slogans like “tuko pamoja” labor to suture inter-community relations damaged when we killed each other during the post-election violence in 2007-2008 — in time for the next election.

The singularity of the post-election violence of 2007/8 in Kenya is disturbing. There was, after all, inter-community violence prior to and after the 1992 and 1997 elections. This violence is not specific to election years. In fact, recent reports of ongoing ethnic clashes around the country suggest that conflicts occur even when not mobilized by politicians. High unemployment, land injustice, drought and food insecurity, and resource depletion — the main causes of conflicts — are not particular to election years.

In truth, the ICC process has delivered little catharsis for Kenyans. While it has been argued that this is the first time senior Kenyan politicians are facing the consequences of being held responsible for wrongdoing, the ICC process has obscured the complicity of ordinary Kenyans in the post-election violence and instead placed full accountability on the four indicted. To make matters worse, Uhuru and Ruto have declared publicly that whatever happens at the Hague will not deter their presidential aspirations. Powerful ethnic lobby groups supporting both politicians have indicated that they’re going to petition the ICC to hold off its trials until after the presidential election in 2013. Although only signatory states can petition the ICC, this move signals that there are interests within the Kenya body politic for whom winning State House is more important than justice and reconciliation with regard to post-election violence 2007/8.

While the ICC process and the Uhuru-Ruto presidential campaign have pervaded the media, coverage of the government’s failure to properly relocate and compensate Internally Displaced Kenyans (IDKs) has dwindled. Five years after post-election violence of 2007/8, there are still about 250,000 IDKs in camps across the country. The government claims most of these Kenyans are opportunists attempting to get free land and compensation. Internally Displaced Kenyans are now viewed as criminals by their own government.

Like IDKs from the 1992 and 1997 elections, those from the post-election violence risk getting forgotten. It is easy to forget. After all, Kenyans displaced by violence in 1992 and 1997 and the years in between and after were forgotten in the sort of Kenyan exceptionalism that portrayed us as peaceful, as never having hacked each other to death or forced people off their land. Before 2007 the Western media referred to Kenya as the “poster child” for peace in East Africa, and far too many of us believed this without irony.

Political campaigns for the next presidential election in 2013 have already hit the ground running. Election season is by far the most cynical time in Kenyan politics. It is easy to be cynical: we’ve heard there’s an arms race in readiness for violence during the next election year; we’ve been told the new constitution, the very document meant to redress some of the longstanding inequalities that led to the post-election violence of 2007 and 2008, is purely “aspirational” — that it is too expensive to implement and it’ll be years before it takes effect.

Now, more than ever, it is important to shun the easy safety of cynicism. Cynicism is part of what got us into post-election violence then—it is the collapse of belief that paved way for the machete to become the arbiter of our national relations. As a nation, our task is now to imagine the impossible. Kenya depends on it.

* Kweli blogs at Bring me the African Guy.

Uganda, now you have touched the women

In October 2011, the Ugandan government sent Ingrid Turinawe to the infamous Luzira Prison–Uganda’s Guantánamo–for the treasonable act of walking to work. This week, the State, again, attacked Turinawe and other women activists for the “crime” of standing, speaking out, driving, and generally being. Big mistake.

In Uganda, on Friday, the police attacked Ingrid Turinawe. She was in her car, driving to a protest meeting. The police dragged Turinawe out of her car, and in full view of smart phones and video cameras, groped and mauled her. They haven’t apologized nor have they ‘explained’. Basically, the attitude is that it’s Ingrid Turinawe’s fault. Women who pursue democracy and autonomy must learn to expect State sexual terrorism. In patriarchal circles, it’s called the ‘price of freedom’, or, more simply, the ticket in.

Women of Uganda refused that lesson. Instead, they took to the streets. They organized. Today, they protested, stripping off their tops, the police attacked, and six women were detained. As Barbara Allimadi, one of the organizers, explained: “We were there to show we’ve had enough, we will not tolerate this kind of behavior.” Others agreed: “We respect our bodies and we expect to be respected.”

But events in Kampala are not without precedent. Remember Mali? “When the protest movement of Malian women erupted in the town of Kati on January 30, few took notice.” That was the spark that kindled the flame that fed the fire that toppled the State that Touré built. Ok, maybe that’s a bit fast and loose with details, but the processes were set in motion by women’s protest that went largely ignored. (They weren’t ignored by Nina Wallet Intalou, the ‘pasionaria indépendantiste’ of the Tuareg movement in exile, and they weren’t ignored by women’s movements within Mali.) And of course, when not ignored, poorly reported, at least in the Anglophone press.

And remember the women’s protests in Malawi? Also in January. Those were in response to assaults on women wearing trousers, in public marketplaces in Lilongwe and Blantyre. First, women organized and protested, and then more and more people began seeing the violence against those women as part of a larger problem, a problem of State. Again, this is a bit quick, and it cannot be said that women caused the death of Mutharika. Nevertheless, Malawi now has a new President, Joyce Banda.

As South African women say, “You strike a woman, you strike a rock.”

The other African election: France’s first round

What is there to say about that other African election, the one in France? Sunday was the first of two rounds in this presidential contest, which is a lot more about Europe—specifically Brussels, but also Berlin—than it is about Africa. Still, it will have real effects on both shores of the Mediterranean and of the Sahara.

Could French African policy could get any worse? Hard to imagine. Both of the front-runners, incumbent Nicolas Sarkozy and Socialist François Hollande, have run against FrançAfrique. That murky phenomenon, which for decades has fused the lowest common denominator interests of ruling elites on two continents, would seem to have run its course, or at least changed its stripes. But what’s replaced it is none too pretty either.

Sarkozy came into office in 2007 looking to put an end to the cozy corruption of FrançAfrique. Things didn’t quite work out that way, and he certainly got off on the wrong foot. Remember the speech in Dakar, when le petit Nicolas went to the Université Cheikh Anta Diop to pronounce with great solemnity that Africa had not “entered into history”? Those were the days. If you teach French-African relations, like I sometimes do, a speech like that is a gift. As Achille Mbembe wrote, all the phantoms and fantasies of the old colonial power were laid bare in it, and a whole library of colonial and racial thought surged back to life, like a zombie in “Thriller.” No better way to make the past urgent than to see it rise from the dead and walk towards you. Nicolas, we’ll miss you…

Since Sarkozy’s Dakar intervention, as Jean-François Bayart has pointed out, French-African policy has been propelled by concerns over terrorism, immigration (legal and clandestine), and drug-smuggling. Sarkozy spent five years picking senseless fights over ‘national identity,’ scape-goating immigrants and fellow citizens, and swinging his weight around militarily (Libya, Chad and Cote d’Ivoire; disastrous raids in Mali in 2010 and Niger in 2011). Add to that the protection of French enterprises in Africa (from cellular companies to uranium mines), and you have a politics to match the man: belligerent, opportunistic, crass, and undignified.

Hollande, on the other hand, is a sober party man. His campaign likes to portray him as a normal guy—as opposed to Sarkozy the “hyper-president”—and the center of his preoccupations is clearly Europe. While he’s talked about Africa as the “continent of the future,” he has also bemoaned the fact that France has been “relegated to an insufficient rank” there. Hollande would like to see that trend reversed, especially in francophone states. He might be right about Africa’s future and wrong about that of French-African relations. After fifty years of FrançAfrique and five years of Sarkozy, it might be too late to redefine a relationship that many on the continent neither need nor want.

What else can we say about round one of this miserable contest? The immigrants did not fare well. Sarkozy, son of an immigrant, did even worse than expected, as did Eva Joly, the candidate for Europe Ecologies-Verts (the Greens), who acquired French nationality by marriage (and who as a former magistrate has a deep knowledge of the rotten nature of French relations with Gabon in particular). But the immigrants, children of immigrants, and so-called ‘visible minorities’ fared even worse. Over the last few weeks, Sarkozy’s desperate dive to the right played to the worst of the xenophobic nationalism that has been part of French politics for decades, and which only seems to get stronger. President of the Republic, proud of the diversity of his first cabinet, by 2012 he could do no better than to authorize the petty contempt and everyday racism endemic to French society (some of my French friends will howl in protest. I say to them: spend a few weeks accompanying a West African to government offices, as I have done, then call me). National Front candidate Marine Le Pen pulled down 18 percent of the vote in the first round, and 30 percent of the workers’ vote (yes, the workers’ vote). If you want to know how frightening that really is, listen to her talk and consider the fact that many of those who voted for her are expected to sit out the second round rather than vote for Sarkozy because he’s not ‘Right’ enough.

Nicolas Sarkozy is a small man, in every known sense of the word, and if he loses on May 6, he will leave the historical stage by what the French call “la petite porte.” May it hit him on the way out.

April 12, 2012

Bamako-sur-Seine

You don't stand in one place to watch a masquerade, as Chinua Achebe famously said. It moves. You move with it. Same goes for demonstrations. On Saturday a few hundred people marched in Paris for peace in Mali. Mostly Malians, as you'd think, but also a few dozen sympathetic observors, several journalists, a well-received Senegalese woman—"Senegal for the return of democracy and peace in Mali!" read her sign—and me.

Funny day, Saturday. A little bit blustery for those who came out dressed in white, as the organizers had suggested. And events were moving fast. Back in Bamako, it looked as if the junta was on its way out, but no one quite knew when or if they would leave. One of the junta's spokesmen in Paris marched with us, looking chilled and diminished in a white dress shirt, surely realizing his star was going to fade. As for Dioncounda Traore, the speaker of the National Assembly, he was said to be en route to Bamako to take up his constitutional role as interim president, contingent on ousted President ATT's resignation (which happened on Sunday; he too wore white). Everyone had had nearly a week to absorb the shock of the military collapse in the North, but the main rebel movement, the MNLA, had just declared the the independence of the northern region they call the 'Azawad.' And then there were the sanctions and ECOWAS' threat of military intervention….

Across town at the National Assembly, as I found out later, other people were rallying in favor of the Azawad. The "Peace in Mali" crowd ended up at the Trocadero, next to the old Musée de l'Homme and across the river from the Eiffel Tower. Still, the MNLA was present over in the 16th arrondisseement, too, if only in the chants of the crowd: "MNLA—assassins!" "MNLA—terrorists!" "MNLA—get out (dégage)!" Both in Bamako and Paris, rumours had been flying fast and furious about the imposition of some vicious pseudo-Muslim vigilantism at work in Timbuktu and Gao, and people waved signs protesting "rapes, pillaging, and violence in the North!" All this was being blamed rather indiscriminately on the MNLA, or "the rebels." Still, when a guy hollered "Down with the Tuareg! Down with ATT!," his neighbors shut him up fast. Nobody wanted to hear the racism, at least not out loud. And as an older lady said, "We're not here to talk about ATT, we just want peace." That was the most popular chant—"Peace! Peace!"—but "Mali is ours!" ("Mali kera awn ta ye!") was the runner-up. Unity and territorial integrity were the words of the day. There were speeches, but I couldn't hear them over the debates, the tam-tam and the jelimuso (griotte), wrapped in a Malian flag, singing into a megaphone. Everyone was earnest, but no-one was optimistic. The tam-tam didn't quite get going, and the words of the national anthem suddenly seemed ambivalent: "O Mali of today, O Mali for tomorrow…"

As we peeled away from the demonstration and headed for the Metro, we crossed some young Senegalese men selling miniatures of the Eiffel Tower. "Why not the statue to the African Renaissance?" asked a passerby.

April 11, 2012

The 19th New York African Film Festival: 'Maami'

The secret to making a good movie about sport is to make sure there isn't any sport in it. Remember 'Invictus'? Remember 'Goal'? Exactly. Distinguished Nigerian filmmaker Tunde Kelani must have known this, because there isn't any sport in his film, 'Maami', even though his hero, Kashy (Wole Ojo), is a global footballing superstar who plays for Arsenal.

Adapted for the cinema from a novel by Femi Osofisan, 'Maami' is the story of Kashy's return to Nigeria in the weeks leading up to the 2010 World Cup. A football-mad nation is wild with speculation about whether or not Kashy will decide to finally play for the Super Eagles and lead Nigeria to certain victory in South Africa, but Kashy has other things on his mind. He returns to Abeokuta, his childhood home, and begins to piece together his bittersweet early years growing up in poverty with his mother. Old and painful memories are stirred up, and must be confronted.

Ayomide Abatti (the young Kashy) and Funke Akindele (Maami, his mother) offer rich and tender performances, and work brilliantly as an on-screen pair (pictured above). Kashy's story is interwoven with sharp social satire, beautifully rendered impressions of Lagos and a superb soundtrack – there's even a cameo appearance by highlife master Fatai Rolling Dollar. This is bold and stylish film-making, and it deserves a wide audience.

Here's the trailer:

'Maami' plays on Monday, April 16, at 8.45pm at the Walter Reade Theater at Lincoln Center. The filmmaker, Tunde Kelani, will be there.

* Africa is a Country is reviewing films from the 19th New York African Film Festival (April 11-17) over the next few days. Also come to the two panels on "Cinema and Propaganda" which we are co-presenting with the Festival on Saturday, April 14, from 1.30-4pm at the Lincoln Center in Manhattan.

The 19th New York African Film Festival: 'Black Africa, White Marble'

From very the opening scenes of Black Africa, White Marble, we learn that Brazzaville, in Republic of Congo, is the only capital in Africa to still carry the name of a European. While Brazza's far more famous contemporary, Henry "Dr. David Livingston, I presume" Stanley, is remembered as the handmaiden who ushered in King Leopold II's barbarity, this film's near-hagiographic treatment of Brazza's life reveals a different direction that the relationship between Africa and Europe might have traversed. Although Pietro Savorgnan di Brazza's name is rarely mentioned when we learn about the history of European contact with Africa during the colonial period, his significance to the formative years of the Congo becomes abundantly evident as the scramble to 'own' his sainthood in the 21st century is chronicled in this film.

Filmmaker Clemente Bicocchi uses an innovative mixture of animation, puppetry (including shadow puppetry), original documentary footage, and extensive interviews with a key member of Brazza's family (writer Idanna Pucci). The opening scenes, where Europe's initial regard of Africans—childlike, savage, and in need of civilization—is narrated by a well-dressed 'African' puppet, removing the scenes of didacticism, but adding a joyful irony. As an audience, we feel like a special audience of children-in-the know, complicit in the knowledge that the stupidity of European thought, of that time, was only rivalled by its self serving nature…we also have the irony of knowing that the same patterns of thought, aided by new corrupt and power hungry rulers, shape Europe's relationship with Africa today. On goes the grasping and greed, with a white marble mausoleum eating the country's revenue, tainting Brazza's memory rather than honouring it.

Much of the film chronicles the contrast in Brazza'a approaches to that of contemporary Europeans: just as Brazza almost willed himself, physically, into hitherto unknown geographical locations, he similarly willed himself intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually into unknown ontological spaces. As a young boy, Brazza was fascinated by the word "Macoco", imprinted on a vast stretch of empty space beyond the charted west coastline at the nape of the African skull. As a young man, when he was employed as a colonial servant in Gabon, he decided to make a journey to this mysterious "white space" in the middle, without a "legion of armed men" to enforce his will as Stanley did, having no weapons and no gold with which to bribe or trade. Instead, he records that he travelled into territories unknown to Europeans as a 'friend,' and was received with hospitality everywhere he went. Finally arriving at the mythical White Space that he chased since childhood, he learns that the word "macoco" means "king." Meanwhile, before Brazza arrives, Macoco Iloo the 1st has had a couple of dreams of his own: that one man will arrive offering loyalty and respect, the other, riches. He, too, has a choice to make. As fate would have it, proto-hippy, 'gone-native' Brazza arrives before the greedy, hand-hacking Stanley, and together with Iloo the 1st, enact a ceremony to 'bury war.' Macoco Iloo the 1st agrees to place his kingdom under French protection.

It appears that the French betrayed both Brazza and the Congolese, ignoring Brazza's report on widespread brutality and macabre acts of the companies that now 'owned' the vast swathes of the interior. When the French parliament learns of the atrocities through Brazza's report, and vote in overwhelming numbers to cover it all up (blaming acts of violence on independent rogue actors), who can fail to draw parallels to the War on Terror? We also realise that the machinations of the late nineteenth century are only rivalled by those of the twenty-first. While Brazza's family want him to be remembered as the man who sacrificed his life trying to prevent the atrocities that befell the region, the current president, shown as a proper sunglasses-at-all-times dictator with an equally sinister retinue, also want to use Brazza's remains to amalgamate power.

Black Africa, White Marble pits tradition against modernity a bit too heavy handedly, but by using an exciting detective-mystery like approach to how the story is revealed, the filmmaker avoids the pitfalls of making the film a didactic history lesson.

The 19th New York African Film Festival: April 11-17

This film festival–still the premier site for African film in New York City and on the US east coast–opens tonight at Lincoln Center with a showing of "Mama Africa," the 2011 documentary by Finnish director Mika Kaurismäki about the life of singer Miriam Makeba "who brought South African music to the world." The well structured documentary, a celebration of Makeba's life, is a mix of archived video footage, and interviews with some of her closest family associates (her grandchildren Nelson Lumumba Lee and Zenzi Monique Lee, former husband Hugh Masekela and musicians Sipho Mabuse, Abigail Kubeka, Angelique Kidjo and Dorothy Masuku.) Other films include "Relentless" (see our review on Friday) "How to steal 2 million," 'Playing Warriors" and "Restless City." The detailed program (and tickets) can be accessed here. Africa is a Country is reviewing a selection of films from the festival (see our timeline). And on Saturday afternoon (1.30-4pm) we're co-hosting two panels on "Cinema and Propaganda" in the Frieda and Roy Furman Gallery at Walter Reade Theater, Lincoln Center. Here's the details:

The popular blog, Africa is a Country (AIAC), will present a two-part panel discussion, on Saturday, April 14, 2012, titled "Cinema and Propaganda". From 1:30pm-4:00pm, join AIAC as featured bloggers and special guests examine, first, the relationship between Africa and the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s, as is evidenced by Russia's extensive film archive of the continent (panelists: AIAC's Basia Lewandowska Cummings and Russian film archivist Alexander Markov), and then, for a second panel, explore the relationship between film and social media movements, including but not limited to Occupy Nigeria, Tahrir revolutionary videos and cinema and #Kony2012, among others. (The panelists for the second panel are AIAC's Sean Jacobs, Boima Tucker, Elliot Ross and Neelika Jayawardane). NO RSVP IS REQUIRED. FIRST COME, FIRST SERVED SEATING, UNTIL VENUE REACHES CAPACITY.

April 10, 2012

Coke and cynicism

I won't bother to unpack this commercial, but this is exhibit A for the case against uncritical boosterism and identity politics. Coco Cola Kenya hijacks "the Africa is booming" discourse to sell more soft drinks. Here's their cynical sales pitch:

There are close to 1 billion people in Africa each with a reason to believe. Because Coca-Cola knows, understands, lives and breathes AFRICA, ONLY COCA-COLA can influence positive attitudes amongst AFRICANS by claiming its role AS the ICON OF HAPPINESS and the BEACON OF OPTIMISM.

Germany's Namibian Legacy

So the German Reichstag have decided again that the systematic murders of four ethnic groups in Namibia between 1904 and 1908 wasn't genocide. Late last month, March 22, the German parliament debated a motion proposed by the Left party to officially recognise the genocide which took place in Namibia between 1904 and 1908. The Namibian confirmed that the motion has been overturned. It is not a coincidence that in a review of Sebastian Conrad's book German Colonialism: A Short History, Richard J. Evans notes that evidence of this history can be seen in present-day Namibia: "If you go to Windhoek in Namibia, you can still pick up a copy of the Allgemeine Zeitung, a newspaper which caters for the remaining German-speaking residents of the town. … In Tanzania, you can stay in the lakeside town of Wiedhafen. If you're a businessman wanting to bulk buy palm oil in Cameroon, the Woermann plantations are still the place to go. In eastern Ghana, German-style buildings that once belonged to the colony of Togo are now advertised as tourist attractions." (London Review of Books) German colonialism in Africa, obscured by the comparatively more substantial colonies of other European countries and numerically superior crimes of the Nazi genocide, occupy a diminished place in German national guilt.

Thousands of Namibian bodies were prepared, with horrific efficiency by women often related to the deceased, and delivered to scientists in Germany schools and universities. These were harvested from locals who had died at the hands of farmers tasked with 'searching the land and disrupting settlements', those interned in camps such as that on 'Death Island', where a scientist called Dr Bofinger was apparently at liberty to experiment on inmates (Pambazuka).

Until last September the skulls of 20 Namibians remained in German archives. 15 were from men, 4 women, and 1 from a boy; it is thought that 11 were from the Nama ethnic group and 9 from the Herero (BBC News). In September an official delegation from Namibia travelled to Germany to recover these remains and return them to formal burial in their home country. The reception of this delegation was deeply controversial, causing new tension between Germany and its former colony, and revealing existing problems in both countries.

Christian Kopp, of the 'No Amnesty to Genocide' organisation, said the German government's treatment of the issue had "seriously damaged diplomatic relations" (allafrica.com). An apology by German minister Heidemarie Wieczorek-Zeul in Okakara in 2004 was dismissed by the government as 'a personal statement' (allafrica.com). Now government minister Cornelia Pieper is accused of leaving a panel discussion with the Namibian delegates. The German government claimed suspicion of the delegation's 'hidden agenda'.

This seems to be a result of in-fighting in Namibia between the victims of German colonialism. Genocide scholar Henning Melber notes in this article that the Herero have in the past claimed that they were the sole victims of the genocide, to the outrage of pepresentatives of the three other groups (Dama, Nama and San). This controversy dogged the centenary commemoration of the start of the 1904 war, and seems to have become Germany's reason for refusing reparations. A spokesperson for the government claimed

"[i]t would not be justified to compensate one specific ethnic group for their suffering during the colonial times, as this could reinforce ethnic tensions and thus undermine the policy of national reconciliation which we fully support.

Thus the imposed emphasis on national unity becomes the basis for this refusal to recognise genocide. As if reconciliation were possible without commemoration. Domestic political tensions in Namibia have recently reproduced the grammar of colonialism:

The latest tension stems from Youth and Sport Minister Kazenambo Kazenambo's (KK) outburst calling his fellow ministers 'stupid Owambos' with a 'Boer' mentality in an interview with Insight Magazine's Tileni Mongudhi a few weeks ago. (In the Namibian and South African context, the term 'Boer', a Dutch and Afrikaans refers to white Afrikaner farmers/settlers dating back to the 17th century, but is also associated with oppression/Apartheid–police where colloqually known as 'Boere'; some white Afrikaans speakers, especially rightwingers, also claim 'Boer' as a political identity.)

KK was the leader of the mission to repatriate Namibian skulls, and this event brings national and ethnic politics into a problematic area of indistinction:

A few months before this latest incident, he hurled racial insults at a white reporter who asked him about the repatriation mission, which he led, for the return of Hereros and Namas skulls (victims of German genocide in Namibia) from Germany. Many Namibians cheered him for standing up against a white person….a 'Boer' for that matter. It is the follow-up questioning to this previous incident that, when asked whether he (KK) acted more as Herero than a minister during the skull repatriation mission, that made him go ballistic and physically threaten the journalist and confiscate his voice recorder (which he described in military language as a captured enemy tool). True to military fashion, KK (through his lawyers) had the voice recorder erased by an expert outside Namibia.

Germany, who have agreed to support the development of football in Namibia, organising youth tournaments in the country, seem unable to provide a meaningful dialogue with the people who have inherited this conflict. University of Michigan academics Julia Hell and George Steinmetz, in an article in the academic journal Public Culture, argue that the lack of a resident population from its former colonies has deprived Germany an intellectual tradition of post-colonial critique.

An interesting post-script to this debate is provided by Jim Naughten's photoseries of Herero people wearing colonial-era German clothes (examples above). This reproduces the Rhenish missionaries practice of 'converting and clothing them after European fashion' as well as Herero traditions: As Naughten writes on his personal website:

Upon killing a German soldier, a Herero warrior would remove the uniform and adopt it to his person dress as a symbol of his prowess in battle. Paradoxically, as with the Victorian dresses, the wearing of German uniforms became a tradition that is continued to this day by Namibian men who honour their warrior ancestors during ceremonies, festivals and funerals.

It would be interesting to learn more about these practices, their role in social life, equivalents in the practices of other ethnic groups and, in particular, whether the comic lens of Naughten's photographs is imposed. In any event, these images suggest a satirical impulse which, in the absence of meaningful official dialogue, seems a powerful and necessary form of post-colonial critique.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers