Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 537

May 9, 2012

‘We found love in a hopeless place’

The central point of this song and music video by violinist Lindsey Stirling (the singer is one Alisha Popat) begins with an invocation of a familiar trope: Africa is a hopeless place. But African love springs eternal. So much so that it has the ability to save and teach privileged people from the west, who arrive with fancy hopes of ‘saving’ picturesque Africans. Hell, I’m sure you could even save the elephants if you spent long enough prancing around them playing the violin and the elephants somehow managed to resist the temptation to grind you into the dust with their massive feet (note to American celebrities). And people love this kind of thing. By late last night, this video had nearly half a million views since it was first posted on Youtube on Monday, May 7.

Once you get over the Johnny Clegg-Ladysmith Black Mambazo echo, and after some violin performances for the requisite gaggle of adorable black school kids (we’ll never get why posing a lone American adult with a bunch of African kids plucks the heartstrings of the Youtube crowd), another performance under an acacia tree (pop up text reminds you “this is their time hearing a violin”), a virtuoso drummer (another local?), and then the gracious sharing of the ceremonial violin with Maasai warrior (another requisite trope of any transformative Africa video), we get the re-minted lyrics: “We found love in a holy place.”

Yup, once again, the amazing transformation that Africa is ever burdened with granting to soul-searching westerners has magically taken place. So: this land is now the tabernacle of God, if not the location of God himself. Deep stuff. In the Rihanna original, of course, the “hopeless place” is basically somewhere where you get to do a vast amount of snogging: snogging in a cornfield, snogging in a skatepark, in a burger-joint, in a car, in a grimy apartment after having taken loads of drugs, in the bath wearing Doc Martens. But no snogging for Lindsey Stirling in Kenya. Instead there’s just a whole lot of very determined and very chaste smiling. Grin and bear it.

They also find ‘authentic’ Kenyan clothing and accessories. (Must be the knockoff Vlisco prints, or the red tartan blankets given to the Maasai by Scottish missionaries?) Sadly, it wasn’t the fantastic young Kenyan designers these people ran into. Imagine the transformation that might have happened. If only. The credits suggest Lindsey et al went to Kenya on the dime of an online retail store, but you wouldn’t know this whole Save the Children thing is about selling clothes.

Meanwhile, however, they find the love in a hopeless place.

* Elliot Ross and Sean Jacobs contributed to this post.

May 8, 2012

Tumblr is a country

We are also now on Tumblr where we post and curate all those things (especially photography and video) that we can’t fit onto the blog or that you miss out of if you don’t check Twitter or don’t mess with Facebook. Bookmark us.

Yuna

Malaysian singer-songwriter Yunalis Zarai sings here in the classic tradition of seafaring island people: the lyrics use the metaphors of water, swimming, and voyaging as an invitation to love. What is different about her words is that it is typically the male figure who approaches the woman, captured in the ‘island’ figure, and the invitation is for her to leave her safety, and be engulfed by the intemperate, vast, and living thing that surrounds her. Instead, Yuna’s words are aimed towards a boy, to whom she beckons.

And she is a scarf-wearing, leather-jacket sporting Muslim. Yeah, the scarfs are tied in knots that would make Erykah Badu take a deep breath.

Yuna sings with the heart-breaking, but sweet (without being saccharine) tonals that remind one of indie-pop singer Feist. Coastals all along the eastern and southern seaboards of Africa have familial, ancestral, and deep cultural ties to Muslims from the island nations of South Asia; in fact, looking at Yuna, I can hardly differentiate her face from mine, or that of many of my friends in Cape Town.

Although she has an unfortunate way of describing herself as a “cross between Mary Poppins and Coldplay,” we’ll put those dalliances down to youthful exuberance. Pharrell Williams just produced her new single, “Live Your Life”, and if he has anything to do with it, her sound will be catchy, her songs will have great hooks, but it won’t be arena-pop. She’s going to be big.

Bom Boy

‘A thing had begun to grow like a tree in Leke’s throat.’ So begins Yewande Omotoso’s Bom Boy, a bright debut novel that sits comfortably in the realm of magic realism, somewhere between folklore, memoir and modern fiction. Leke Denton is the son of a Nigerian father and a “coloured” South African mother, who through uncontrollable circumstances gives baby Leke for adoption to a White Capetonian couple, the loving Jane and the well-meaning Marcus. After Jane dies due to a sudden illness, Leke is left even more lost in a city that specializes in alienation. As a young adult he becomes reclusive and starts stalking people; he makes endless doctor’s appointments and false check ups in order to have basic human contact. He eventually finds out through old letters from his biological father about a family curse, and he starts piecing his past together.

I found the book to be genuinely refreshing, with characters that constantly surprised me; they all unraveled very gently throughout the narrative like flowers in bloom. (Which works for this romantic.) Just when you think you’ve figured the characters out, the author opens them up a little more, and our perceptions change.

Yewande told me she wanted the reader to “be compelled to consider their own prejudices, and the shortcomings of these. Mostly I wanted people to experience compassion for the characters, to be unable to simply write even the most difficult of characters off.”

A Cape Town based architect “by day,” Omotoso had to wake up at 5am every morning and write for two hours before it was time to leave for work. She describes it as somewhat of a “military operation.” She comes from a family of writers, and completing a novel was something she had wanted to do for many years. Her father, Professor Kole Omotoso has written five novels, not to mention a plethora of academic publications, plays and literary critiques. Fun fact: he is famously known in South Africa as the “Yebo, Gogo” man in the Vodacom commercials from the late 90s-early 2000s. Her brother is the well-known and respected filmmaker/writer/director Akin Omotoso (remember his ‘God is African’, but he also has recently completed a new feature — ‘Man on Ground’ — tackling the South Africa’s xenophobic streak). I mention to Yewande that Bom Boy would make a great film and asked whether a sibling collaboration is on the cards. “We’ve spoken about it. I think we’d like to do something together in the future.”

Bom Boy is a debut novel that deserves your attention. As Tade Ipadeola writes in the Lagos Review of Books, “I hope, sincerely, that this golden debut fills every barren space on the continent from the Karoo to the Sahara with the chlorophyll of hope…” So do we.

Read an excerpt of Bom Boy here.

May 7, 2012

‘We’ve always been migrating’

Bentley Brown, director of the exciting new film ‘Faisal Goes West’, spoke with me about migration, building a cinematic bridge between Sudan and America, and lawyers turned pizza delivery boys.

Could you tell me a bit about how ‘Faisal Goes West’ came about?

Well, the story is about Faisal, a young man in a family who move from Sudan to the US. We never specifically mention why they move from Sudan to America, but it’s implicit; in the US, its usually the case that if you come from that part of the world, you either come on a green card lottery visa, or seeking political asylum, claiming refugee status. But, in the film, we never specifically address this. We don’t want to get into politics, we want to tell the global story of migration.

In this way, the film highlights a more global story, of human (in)equality, the dignity and indignity of the migrant experience, as you know — especially in the US and parts of Europe, people coming from Africa are often profiled in a negative light, never given the benefit of the doubt that they are intellectual human beings. This is something our film feel seeks to question. Specifically, in ‘Faisal Goes West’ we are focusing on a reality in America, on the absolute over qualification of immigrants. For example, in the story Faisal’s father was a professor in Sudan, but now in America, he is first a mechanic, then a taxi driver. This mirrors the lives of many people who arrive, in fact one of our main actors has a similar experience himself; he came on a green card lottery from being a lawyer in Sudan, now he’s delivering pizzas.

In an interview with the BBC, you said something that interested me; you said, ‘we’ve always been migrating’. How do you think your film distils this general fact of contemporary existence into the singular story of Faisal?

Well, I wrote the film based on my experience moving from the US to Chad. My main actor, who is Sudanese born, moved to Egypt and then to Kansas. All of us involved had something particular to us, and this experience to draw upon. We had all moved from one place to another; there is a shared sentiment, a shared approach.

But even overall, America is a land of immigrants, though it seems to forget this on a daily basis. People are very fast to forget their migrant histories — anywhere in the world in fact … Sudan, Chad, anywhere. In that interview with the BBC, I said, “there is no such thing as a native”, and behind the glass my executive producer, who is from Sudan but living in the UK was waving his arms in panic, telling me not to say this, there are whole political parties based on the idea of native.

But for me it’s a myth, I mean the US brags about its constitution, showing off about tolerance and equality — but it still promotes this shocking notion of an American identity and ethics. So, I think this film speaks to two kinds of audience in the US. Firstly, to a generation of migrants, for whom there are direct parallels with the story told in the film. The second audience are the Americans who don’t really have a conception of their migration to the US: America is very quick to assimilate. In the 60s and 70s, immigrants specifically moved away from speaking any languages other than English, but this is an important debate; should other languages should be ‘official’ US languages; Arabic, Korean, Chinese, Spanish?

So I want the film to be a window into the American experience — a window into a life that happens every day, but isn’t really noticed.

Could you tell me a little bit more about the cast? How did you all come together?

I have worked a little bit in political analysis, but my passion is filmmaking, ever since growing up in Chad, I made films. I have a film belief in art; art as a way to transcend politics, or stereotypes, to transcend the imagined boundaries we have between us, and to deal with the problems and questions that politics throws up.

When we had our fundraiser on kickstarter — I had a lot of people contact me who wanted to get involved in some way, lots of people — from Sudan, from the Sudanese diasporas, people from the US. That’s how we found our lead actor: at first, he wanted to donate some music, but instead we asked him to audition. Funnily, I had two pitch videos; one in Arabic and one in English. The English speaking one had at most 2000 hits, but the the Arabic one got 250 000 hits, but that’s not the original video I made, instead it was continual re-edits that people made; downloading and re-naming, re-cutting. It was brilliant, bringing people together to contribute, to discuss. After all, identity is only what we make of it.

And when can we expect to see the film?

We’re at the rough cut right now, we’re in the Cannes short film corner in a couple of weeks. The biggest thing for us is that we don’t want to compromise the film’s quality; we want some time, to compose, to finish the music and sound. There are so many contributions by Sudanese and American artists … it’s all very exciting.

As a medium length feature, our most natural market will be TV; in Chad, Sudan, the Middle East, network channels. In the US, it will be limited to smaller independent networks. One of the things that is on our side is the shifting away from DVDs to film on demand — we can reach the whole world with that.

After all, I want this film to be a platform, to get people to work together, to talk, to discuss through the power of drama, this fictional story. When I wanted to tell this story, fiction was the first that came to mind; it allows limitless freedoms. I love to give everyone involved to have freedom, to improvise and author the story in their own way.

* You can support Faisal Goes West on Indiegogo to help them reach their production costs, and you can read more about Bentley here.

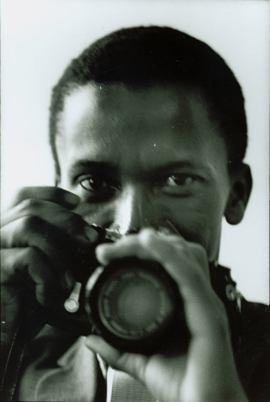

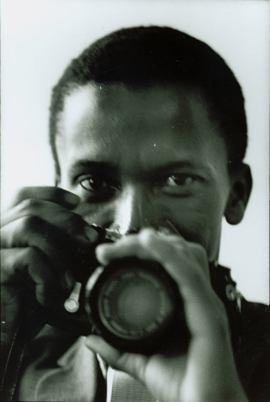

The ‘passing’ of Ernest Cole

Information on famed South African photographer Ernest Cole’s decision to ‘pass’ from ‘African’ to ‘coloured’ in Apartheid South Africa’s kafkaesque “race classification system” is not readily available beyond the ready-made theories and rationalizations repeated in museum catalogues or on websites. From those sources we get glimpses of his anxiety or the stress the decision brought on his family in short scenes from the only documentary film on Cole’s life, that by the photographer Jürgen Schadeberg. But even then, Schadeberg’s film neatly sidesteps the issue of passing by not probing Cole’s motives. Like with play-whites (coloureds who passed for whites), we won’t know how many ‘play-coloureds’ there were. What the writer Zoe Wicomb has said of play-whites applies: “We don’t even know how many of them there are. There’s no discourse, nothing in the library, because officially they don’t exist [anymore].”

Catherine Dilokweng Hlongwane (Cole’s sister):

[My brother, Ernest] did a funny thing. He started stretching his hair … My mother [Martha Kole] was worried. He did not want to tell the truth … [Finally] he said, ‘I don’t want this pass. I want to be a coloured’. (in Schadeberg’s ‘Ernest Cole’)

Struan Robertson, photographer (and an associate of Cole):

Other friends had been [through the experience before] him. (ibid.)

Jan Raats, the director of the apartheid government’s census:

(1) Asiatic means a person of whose parents are or were members of a race or tribe whose national or ethnical home is Asia, and shall include a person partly of Asiatic origin living as an Asiatic family, but shall not include any Jew, Syrian or Cape Malay; (2) Bantu means a person both of whose parents are or were members of an aboriginal tribe of Africa, and shall include a person of mixed race living as a member of the Bantu community, tribe, kraal or location, but shall not include any Bushman, Griqua, Hottentot or Koranna; (3) Coloured means any person who is not a white person, Asiatic, Bantu or Cape Malay as defined, and shall include any Bushmen, Griqua, Hottentot or Koranna; and (4) a white person means a person both of whose parents are or were members of a race whose national or ethnical home is Europe, and shall include any Jew, Syrian or other person who is in appearance obviously a white person unless and until the contrary is proven.

Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole successfully applied to be reclassified from African to Coloured in 1966. He was 26 years old.

A few months after he successfully applied to become coloured, Cole left for the United States, where he died in 1990 as a black man.

We don’t know why Cole decided to become coloured apart from the political motivations suggested by his friends and passed down in museum catalogues, Wikipedia, or reviews of his work. These are: a coloured ID card would mean less harassment when photographing Apartheid; it would make it easy to obtain a passport. There are only questions.

Who helped Cole’s prepare for his question to become coloured?

Did he look or sound like a coloured? Like ‘A Pretoria coloured’? What do Pretoria coloureds sound or look like?

Did Cole ‘act coloured’ around his mother and sisters after he successfully passed?

Did some members of his family see him as a ‘race traitor’? Did they admire his decision?

What kind of coloured did he become? ‘Other Coloured’? ‘Malay’? ‘Cape Coloured’?

In the 1950s at least 10 percent of whites were coloureds passing for whites. How many ‘Africans’ passed for ‘coloureds’?

What about Cole’s anxieties? There are too many problems with the certainty attached to his motives (mentioned at the outset here).

How does becoming coloured make it easier to leave 1960s South Africa? Are there reports or other instances of this? Were there laws or procedures that made it easier for coloureds to leave?

It seems strange that Cole decided to apply to be reclassified for coloured so soon before he left South Africa for the United States (a country where such distinctions among black people did not have the same currency or legal status). When he arrives in the US, he settles in Harlem—where black nationalism is growing and differences among black people, i.e. class and color prejudices, are played down or actively resisted and collusion with official categories or discourses are frowned upon. Politically and culturally his neighbors in Harlem are and want to black (this is after all the time when Negroes become Black and later African American).

How does being a South African coloured figure or play into this new world he enters in the United States? What privileges come with being a South African coloured in America?

Why was he so focused on becoming coloured when his work is more interested in the apparent certainties of Apartheid black and white binaries?

* This is a slightly edited version of a piece originally written for the exhibition “PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes” (curated by Gabi Ngcobo) in the offices of a former Pass Office in Johannesburg.

The Passing of Ernest Cole

Information on South African Ernest Cole’s decision to pass for coloured is not readily available beyond the ready-made theories and rationalizations repeated in museum catalogues or on websites. We get glimpses of his anxiety or the stress the decision brought on his family in short scenes from the only documentary film on Cole’s life, that by the photographer Jürgen Schadeberg. But even then, Schadeberg’s film neatly sidesteps the issue of passing by not probing Cole’s motives. Like with play-whites (coloureds who passed for whites), we won’t know how many ‘play-coloureds’ there were. What the writer Zoe Wicomb has said of play-whites applies: “We don’t even know how many of them there are. There’s no discourse, nothing in the library, because officially they don’t exist [anymore].”

Catherine Dilokweng Hlongwane (Cole’s sister):

[My brother, Ernest] did a funny thing. He started stretching his hair … My mother [Martha Kole] was worried. He did not want to tell the truth … [Finally] he said, ‘I don’t want this pass. I want to be a coloured’ (in Schadeberg’s ‘Ernest Cole’).

Struan Robertson, photographer (and an associate of Cole):

“Other friends had been [through the experience before] him” (ibid.).

Jan Raats, the director of the apartheid government’s census:

(1) Asiatic means a person of whose parents are or were members of a race or tribe whose national or ethnical home is Asia, and shall include a person partly of Asiatic origin living as an Asiatic family, but shall not include any Jew, Syrian or Cape Malay; (2) Bantu means a person both of whose parents are or were members of an aboriginal tribe of Africa, and shall include a person of mixed race living as a member of the Bantu community, tribe, kraal or location, but shall not include any Bushman, Griqua, Hottentot or Koranna; (3) Coloured means any person who is not a white person, Asiatic, Bantu or Cape Malay as defined, and shall include any Bushmen, Griqua, Hottentot or Koranna; and (4) a white person means a person both of whose parents are or were members of a race whose national or ethnical home is Europe, and shall include any Jew, Syrian or other person who is in appearance obviously a white person unless and until the contrary is proven.

Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole successfully applied to be reclassified from African to Coloured in 1966. He was 26 years old.

A few months after he successfully applied to become coloured, Cole left for the United States, where he died in 1990 as a black man.

We don’t know why Cole decided to become coloured apart from the political motivations suggested by his friends and passed down in museum catalogues, Wikipedia, or reviews of his work. These are: a coloured ID card would mean less harassment when photographing Apartheid; it would make it easy to obtain a passport. There are only questions.

Who helped Cole’s prepare for his question to become coloured?

Did he look or sound like a coloured? Like ‘A Pretoria coloured’? What do Pretoria coloureds sound or look like?

Did Cole ‘act coloured’ around his mother and sisters after he successfully passed?

Did some members of his family see him as a ‘race traitor’? Did they admire his decision?

What kind of coloured did he become? ‘Other Coloured’? ‘Malay’? ‘Cape Coloured’?

In the 1950s at least 10 percent of whites were coloureds passing for whites. How many ‘Africans’ passed for ‘coloureds’?

What about Cole’s anxieties? There are too many problems with the certainty attached to his motives (mentioned at the outset here).

How does becoming coloured make it easier to leave 1960s South Africa? Are there reports or other instances of this? Were there laws or procedures that made it easier for coloureds to leave?

It seems strange that Cole decided to apply to be reclassified for coloured so soon before he left South Africa for the United States (a country where such distinctions among black people did not have the same currency or legal status). When he arrives in the US, he settles in Harlem—where black nationalism is growing and differences among black people, i.e. class and color prejudices, are played down or actively resisted and collusion with official categories or discourses are frowned upon. Politically and culturally his neighbors in Harlem are and want to black (this is after all the time when Negroes become Black and later African American).

How does being a South African coloured figure or play into this new world he enters in the United States? What privileges come with being a South African coloured in America?

Why was he so focused on becoming coloured when his work is more interested in the apparent certainties of Apartheid black and white binaries?

* Originally written for the exhibition “PASS-AGES: References & Footnotes” (curated by Gabi Ngcobo) in the offices of a former Pass Office in Johannesburg.

The other African election, Round 2: Sarkozy K.O.’d

Paris 20ème, Sunday, 8 p.m. Shouts, people banging pots from the windows, children running in the streets—in our neighborhood of workers and immigrants everybody else is upstairs, glued to the television. A man—African by his accent—is declaiming from his balcony. In the empty backstreets, a woman comes up to us in tears, “it’s too beautiful—Hollande won!” In round two of France’s presidential elections, Nicholas Sarkozy is K.O.’d.

Soon, cold beers are selling briskly in the corner stores, and a steady stream of people is heading for the Bastille. On the television, everyone is talking about 1981—the last time the Left ousted an incumbent. Most of us in the street are too young to remember that, but the debates would probably be familiar. The Right says France is living above its means. The Left says it’s lost sight of its principles.

Sober voices—and a few intemperate ones—are going to say that Hollande’s victory breaks the neoliberal alliance at Europe’s heart, that the gospel of austerity preached by Sarkozy and Angela Merkel, his German counterpart, will no longer be an article of faith. The Left Front coalition is pushing for a rise in the living wage and for an earlier retirement age. The Right trades blows on the television—is the National Front responsible for this defeat, or is it Sarkozy’s fault? Marine Le Pen, the National Front candidate who was knocked out in the first round, laps this up like an alley cat with a bowl of milk. Having scored well two weeks ago, she had her supporters cast blank ballots in round two, a strategy that Sarkozy’s spokeswoman condemns as irresponsible. As for Sarkozy himself, he takes the blame for his defeat, because, he tells us, that’s the kind of person he is. Thanks, Nicolas, but the voters know what kind of person you are. That’s why you lost.

What does all that mean for French-African politics? It’s hard to tell what will next emerge from that fetid swamp. There’s talk that Hollande will give a rebuttal to Sarkozy’s infamous Dakar speech of 2007, but that probably matters a lot less in real terms than does French support for the Tuareg rebel movement in the Malian Sahara, the MNLA. It’s obvious, but its depth is unknown. But if the Left is going to talk about principles that are—in the French sense—Republican (secularism, solidarity, brotherhood), backing an ethno-nationalist movement that opens the door to well-armed Islamists would be at best incoherent, at worst, opportunistic and mis-guided. But never say never.

Whether or not Hollande will change things, the essential point is that Sarkozy is gone. On the way to the Bastille, an Ivorian behind us shouts, “He didn’t quit, he was fired! And we’re going to cut his salary for the month!” With 52% of the vote, Hollande might have created his first unemployed citizen, but the brass bands are swinging along the boulevard. It’s a street party, and the gutters are cluttered with empty champagne and beer bottles. A young woman breaks from a sing-along and calls out to a West African woman and a white guy who are holding hands: “Yo, the lovebirds, did you vote Hollande?” “We’re foreigners,” they say. “Well then, you didn’t vote, but you won.”

The other African election, Round Two: Sarkozy K.O.

Paris 20ème, Sunday, 8 p.m. Shouts, people banging pots from the windows, children running in the streets—in our neighborhood of workers and immigrants everybody else is upstairs, glued to the television. A man—African by his accent—is declaiming from his balcony. In the empty backstreets, a woman comes up to us in tears, “it’s too beautiful—Hollande won!” In round two of France’s presidential elections, Nicholas Sarkozy is K.O.

Soon, cold beers are selling briskly in the corner stores, and a steady stream of people is heading for the Bastille. On the television, everyone is talking about 1981—the last time the Left ousted an incumbent. Most of us in the street are too young to remember that, but the debates would probably be familiar. The Right says France is living above its means. The Left says it’s lost sight of its principles.

Sober voices—and a few intemperate ones—are going to say that Hollande’s victory breaks the neoliberal alliance at Europe’s heart, that the gospel of austerity preached by Sarkozy and Angela Merkel, his German counterpart, will no longer be an article of faith. The Left Front coalition is pushing for a rise in the living wage and for an earlier retirement age. The Right trades blows on the television—is the National Front responsible for this defeat, or is it Sarkozy’s fault? Marine Le Pen, the National Front candidate who was knocked out in the first round, laps this up like an alley cat with a bowl of milk. Having scored well two weeks ago, she had her supporters cast blank ballots in round two, a strategy that Sarkozy’s spokeswoman condemns as irresponsible. As for Sarkozy himself, he takes the blame for his defeat, because, he tells us, that’s the kind of person he is. Thanks, Nicolas, but the voters know what kind of person you are. That’s why you lost.

What does all that mean for French-African politics? It’s hard to tell what will next emerge from that fetid swamp. There’s talk that Hollande will give a rebuttal to Sarkozy’s infamous Dakar speech of 2007, but that probably matters a lot less in real terms than does French support for the Tuareg rebel movement in the Malian Sahara, the MNLA. It’s obvious, but its depth is unknown. But if the Left is going to talk about principles that are—in the French sense—Republican (secularism, solidarity, brotherhood), backing an ethno-nationalist movement that opens the door to well-armed Islamists would be at best incoherent, at worst, opportunistic and mis-guided. But never say never.

Whether or not Hollande will change things, the essential point is that Sarkozy is gone. On the way to the Bastille, an Ivorian behind us shouts, “He didn’t quit, he was fired! And we’re going to cut his salary for the month!” With 52% of the vote, Hollande might have created his first unemployed citizen, but the brass bands are swinging along the boulevard. It’s a street party, and the gutters are cluttered with empty champagne and beer bottles. A young woman breaks from a sing-along and calls out to a West African woman and a white guy who are holding hands: “Yo, the lovebirds, did you vote Hollande?” “We’re foreigners,” they say. “Well then, you didn’t vote, but you won.”

Fighting Pop

Congolese/South African (via Belgium) musician Yannick Ilunga, AKA Iamwaves, has been rather busy lately. His group Popskarr, a new ‘electronic/Nu Disco/Misty Pop’ outfit, has just released a stylish single called Fighter; and as his alter ego Petite Noir he has released a mixtape for Okayafrica’s ‘Africa in Your Earbuds’ series (which earned him a tweet shout out from Questlove of The Roots) and a new video for ‘Till We Ghosts’ (above). He calls the music he makes ‘Noir Wave’, an African take on New Wave and Post Punk. It’s an interesting scene to be in, one that has produced genre-busting electronic acts such as Spoek Mathambo and (my personal favorite) Dirty Paraffin. While both those acts have been truly groundbreaking (both equally Afrocentric), Popskarr/Petite Noir’s nod to Bloc Party front man Kele Orekere’s solo stuff is unmistakable, including all the hipster-pandering that comes with it. However, this is something that — with a bit of guidance and experience — Yannick can easily outgrow over time. Personally, I’m looking forward to his future releases.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers