Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 538

May 5, 2012

A French migration fairytale and other films

In his new film ‘Le Havre’, the Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki has beautifully weaved a whimsical, somewhat timeless portrayal of France — all baguettes, bars à vins and shoe-shine boys — with an unavoidably contemporary problem that plagues France’s ports, and moves in tides through its politics (the recent support for Marie Le Pen a good example); immigration.

Paying homage to French cinema, skilfully but without pastiche adopting the composed, poetic style of Bresson and Renoir, Kaurismäki has made a stylistic yet subtle film about exclusion, exploring in a most delicate way the seeping of suspicion and xenophobia that — since France’s colonial exploits — have grown in parts of French society.

The film follows the poor, one time bohemian now railway station shoeshiner Marcel Marx (André Wilms), who drinks too much, works too little, and is hopelessly, haphazardly in love with his wife, and his dog, and perhaps life too. Eating lunch on the steps of the port one afternoon, a young Congolese boy appears suddenly. “Is this London?”, he asks, half submerged in the murky port water. “Is that where you want to go? That’s the on other side,” Marx replies, gesturing to the opposite side of the channel. But of course, the young boy Idrissa (Blondin Miguel) doesn’t leave, and instead Marcel offers him shelter and they begin a friendship, hiding from the farcically dressed ‘villain’-turned-benevolent detective Arletty.

Although the film makes something of a fairytale out of a serious social question, it beautifully, suggestively re-imagines the role and image of migrants in the stylish idyll of nostalgic France; where do the shipping containers full of dehydrated migrants fit into a baguette-ed, beret-ed charming small town, filmed in the colours and composition of a Tati film? Can they co-exist? Are they compatible? Surely they are both as much a part of French history.

When a shipyard guard hears a sound from inside a locked container, a troupe of policemen, doctors and detectives turn up, and with great ceremony prise open the doors. “What’s this?” a bystander asks, “the living dead,” the guard replies. The migrants are put into detention centres, or shipped back to their home countries, and Kaurismäki seems to limply point to the now infamous French detention centres like Sangatte. It’s a contentious issue, particularly since the steady flow of criticisms by groups like Amnesty International who have observed consistent mistreatment in many French-run detention and ‘holding’ centres.

This is Kaurismäki’s first in what he intends to be a trilogy of films set in ports, but it seems to be amongst a remarkable amount of new films in recent months that have used migration, detention and illegal sea crossings as their subject matter.

Films such as ‘The Colour of the Ocean’ by Maggie Peren, ‘Special Flight’ by Fernand Melgar, ‘Terraferma’ by Emanuele Crialese, ‘A Chjàna’ by Jonas Carpignano, ‘Mare Nostrum’ by Andrea Kunkl, Giuseppe Fanizza and Giorgia Serughetti, ‘[S]COMPARSE’ by Antonio Tibaldi, ‘Qu’ils reposent en révolte’ by Sylvain George, ‘The Invader’ by Nicolas Provost or ‘Ferrhotel’ by Mariangela Barbanente, have all examined the issues in various filmic ways. Clearly, it is a pressing, important subject matter. The horrific news story that told of 70 Libyan refugees left to die in the Mediterranean Sea speaks of the dubious attitudes held toward migrants by large European, multinational authorities and institutions.

* You can read my reviews of ‘The Colour of the Ocean’ and ‘Special Flight’ (which were screened as part of the London Human Watch Rights Film Festival) here.

*Co-written by Tom DeVriendt

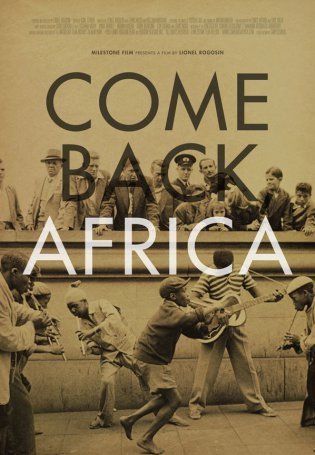

Classic African Films N°3: ‘Come Back, Africa’ by Lionel Rogosin

‘Come Back, Africa’ (1959) is an explosive film; a strongly political piece, its show the hardship, joy and pain of township life, otherwise closed to the world by the Apartheid regime’s strict hold. Enriched through Lionel Rogosin’s collaboration with the Drum writers Lewis Nkosi and Bloke Modisane on the script, the film possesses a ‘Kafkan sterility’ (Modisane 1990), and tells the archetypal story of the rural man forced toward the city through hardship and the prospect of a better life, something Modisane speaks of with bitterness in his autobiography Blame Me On History (published in 1963).

Modisane described the protagonist, Zachariah, as a ‘simple rural African’ with stereotypical characteristics of being ‘inarticulate, halting in speech, with very little education’, and yet, ‘he was a man…with quiet dignity and tremendous integrity’. This mixture allows ‘Come Back, Africa’ to screen as an intricate portrayal of the development of a ‘black consciousness’; throughout the film, Zachariah becomes politicized and emboldened through the injustice he suffers, and through beautiful filmmaking his subjectivity develops in powerful contrast to the racist reduction of the black subject to second class — devoid of complexity, emotion or autonomy.

The South African Information Service managed to maintain a level of ambivalence toward South Africa in the US with its persistent offering of South African films at little or no cost but which inevitably explained apartheid in a positive light (Pfaff 2004). ‘Come Back, Africa’ is a break with this trend; it was made independently by Lionel Rogosin, who had already made a name in the U.S as an activist cineaste for his film ‘On the Bowery’ (1957). Told to seek out Modisane, and later, Nkosi, Rogosin’s immersion in Sophiatown through ‘Drum’ eyes enabled ‘Come Back, Africa’ to be made in line with Rogosin’s intention, which was to ‘reflect [black South African] realities’ (Pfaff).

One of the first scenes features Zachariah, sitting on his bunk while working in a gold mine, writing a letter of lament to his mother. Speaking for the first time in English, a low-shot captures Zachariah narrating his own suffering. This is indicative of one of the film’s aims — and that of ‘Drum’ magazine in general: rather than be presented as the disenfranchised, passive African, Zachariah is providing the narrative to his own experience, rather than it being defined elsewhere.

As a historical document, ‘Come Back, Africa’ captures Sophiatown before its demolition, and the cultural riches which were contained within it, including the debate and discourse of the young intellectual class featured in the shebeen scenes. Rightly described by Nkosi as ‘urbanized, eager, fast-talking and brash’ (in Modisane 1990), the political debate over white liberals and their discussion of Marumu’s morality is riveting. ‘If I could get that much color off you’ one of the drunk intellectuals laughs, ‘I could liberate you that much’. In the famous shebeen scene, which features a stupendous performance by the impossibly young Miriam Makeba, they discuss the liberal view, ‘embodied’ in Alan Paton’s book Cry The Beloved Country (1948). They laugh at the liberals, saying they are ‘three days late’, and that they do not want a ‘grown up African’.

While they are talking and laughing, Zachariah stays quiet, and admits that he does not understand their talk. And yet, he agrees — ‘I like it’. It seems to be the beginning of his development of a politicized, black consciousness. This can be linked to the wider emergence of a movement of the same name, which, framed by the tragedy of the Sharpeville Massacre, prompted writers and poets to produce work under this new subjectivity. ‘Come Back, Africa’ is as much a homage to Sophiatown as it is a narrative of hardship. For Modisane, the destruction of Sophiatown was a terrible loss; ‘there was another death gaping at me; I turned away from the ruins of the house where I was born in a determination not to look upon this death of Sophiatown’. The township became a defiant space, a ‘living symbol’ where the art of survival was celebrated, through song, literature and music. This prominence of music in the film is both a testament to Sophiatown’s beauty and a soundtrack of its oppression.

In the painfully beautiful scene at the end of the film, Rogosin captures Zachariah’s wife as she hums mournfully, waiting for his return from arrest. The trembling whistle becomes the woeful final soundtrack to Sophiatown, with panning shots of the cityscape — its pre-emptive melodic obituary.

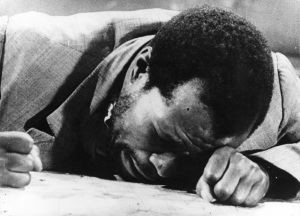

‘Come Back, Africa’ offers no light at the end of the tunnel as Hollywood has us accustomed to. Zachariah falls apart on-screen at the discovery of his wife’s murder. Their relationship has been given depth; their tender kiss is in contrast to the blatant sexuality of Hazel (and even to Makeba’s untouchable glamour) and it seems to present black sexuality as far distant to the white stereotype of an animalistic, uncontrollable sexuality.

Zachariah’s anguish is difficult to watch. Modisane writes: ‘the crack up of the character, and the man, were so closely linked that we were horrified to be in the presence of the destruction of a man. It was a nightmare we could not control or stop or turn our faces from’. It is this destruction that ‘Come Back, Africa’ makes clear to the viewer. Unlike the Rev Kumalo, Paton’s hero, Zachariah embodies none of the ‘white liberal’ politics, what Modisane calls ‘a cunning expression’. Rather, he was just a man asked ‘to live again his life before the camera’ and it is for this reason that Zachariah’s performance ends with such harrowing gravitas, accompanied by an electrifying soviet-style montage, bringing to culmination the theme of the drumming soundtrack, the relentless oppression and hardship and his heightened political and emotional subjectivity.

* Elliot Ross also wrote a review of this film on AIAC here, when it was screened at the Film Forum in NYC.

May 4, 2012

Friday Bonus Music Break

Your weekly #musicbreak roundup. Mokobe and Oumou Sangare pray for peace in Mali:

Yasiin Bey, Dead Prez and mikeflo’s Trayvon Martin Tribute:

Finest South African hipsters Dirty Paraffin (HT/ Phiona):

Optical Illusion and friends (H/T Mikko) — the video comes with a long by-line, but the track itself will do:

Finland’s Gracias:

Stephen Marley went to Africa and returned with this video:

From Namibia, not your ordinary Nam tune:

Chris Dave (H/T Okayafrica) gives Fela (and Tony Allen) the remix treatment:

Finally, I was 13 when my taste in music took a drastic turn. R.I.P. MCA.

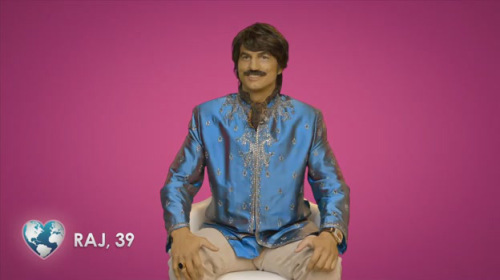

Brownface

Ashton Kutcher, known for his unusual savvy when it comes to investing in tech companies, and for actually being a presence in those spaces (attending conferences and personally meeting startup founders), must know that many of those technical companies have key employees or founders of South Asian descent. So imagine the surprise of many when Kutcher appeared in ‘brownface’, and offended many. Many in the Indian diaspora were asking: “Why is it totally unacceptable to do blackface, but ok to do brown/yellow face in the US?” Even Gawker, known for being on top of the game, posted a somewhat inane take on the issue, taking no particular stance.

The advert for Popchips was conceived and put together by the (ironically named) firm Zambezi; the PR firm that promoted this campaign proudly is Alison Brod PR. Their conceit? Kutcher takes on the persona of five different characters, each a bachelor trying his luck on an Internet dating site: World Wide Lovers. How does Kutcher tackle five different personas? Does he go through the rigours of method acting, or Meryl Streep himself into an otherworldly rendition of an Other? Nah, this is the man who made his name on That Seventies Show. Kutcher takes a well-travelled path to transformation: wearing outlandish outfits, donning facial hair and wigs, and attempting some foreign accents. Worst of all? None of the personas are funny.

So why did such a uninteresting advert get people’s attention? It was the Bollywood Director persona, in which Kutcher is in ‘brownface,’ speaking some boring lines in a badly imitated version of the accent that made Apoo (and Hank Azaria, the actor that provides many of the Simpsons’ character voices) a household name in the US. Indeed, many Indians speak accented English – some deeper than others, and varying by region – no news there. My 8th grade Math teacher, Mr. Dubey, spoke a much finer version of Kutcher’s attempted accent as he extolled the virtues to be found in the universal language of numbers. As I grew up, my sisters and I prank called unsuspecting housewives across the Copperbelt Province in Zambia, and one of the accents we used was Mr. Dubey’s thrillingly accented English. Of course, we loved the accent, we joked about it, and…we didn’t want to be associated with it, either: that accent was one of those things marking South Asians as not ‘civilised’ enough for the transformation that was expected of us at the far reaches of Empire. But as I grew older, I realized: the beauty of such accents! What fine variations of the language! And I wondered, at the risk of sounding like a caricature of Chimamanda Adichie’s “If you only hear one story about X, that is the only one you know”: if the only Indian that Americans know about is the 7-11 Apoo, how impoverished will our collective expectations be?

Obviously, those Indian-Americans who shared chunks of their own startup companies, and bet on their futures together with Kutcher went straight online to voice their upset. They felt, as did Anil Dash, that “the onus is on [Kutcher] to respect his business partners.” Dash went on to offer a superb list of What to Do When Your Company Makes a Racist Advert in his blog. (Read it – it’s brilliant. He even refers readers to Jay Smooth’s How To Tell People They Sound Racist.)

Still, people who were weaned on the One Story of Apoo from the Simpsons were left wondering why people were so offended. On Gawker, Kelly Cameron asked, in true ingénue fashion:

Is that really racist? It’s stupid, yes, but he’s playing an Indian, so he’s wearing make up. Is it inherently racist to play someone from an ethnic group you don’t belong to? To me, racism is saying that your group is better than another group or groups. I don’t see that this ad even criticizes Indians, or necessarily even the fake Bollywood producer.

But the Internet happily produced this amazing anecdote too, by John O’D:

I am reminded of the actor Sayeed Jaffrey’s comment (on BBC radio some years ago) on Peter Sellers’ portrayal of an Indian doctor in the film The Millionairess. “Such a shame he played a character with a north Indian name with a south Indian accent.” One of the great put-downs.

Lovely.

This is not to say that Indian advertising is free and clear of racism: recently, a Bollywood director shocked people when he opined that light skinned actors were better for filming, because dark skinned people’s featured don’t show up. (He was only openly wording the widespread, internalized racism towards people with dark skin, a bias that spawns skin-lightening creams and matrimonial adverts extolling the virtues of “fair” daughters throughout South Asia.) And Indian adverts used racist caricatures of “African Bushmen” without imagining they would raise a hair (see my colleague Sean Jacob’s post about some of the adverts). These adverts also employ a version of ”brownface” and racist caricatures to sell soft drinks. The ad-makers defend it all as “funny” and “what’s the problem?”

I’m certainly not saying: “Indians do racist caricatures, so Americans doing it is ok,” but as long as we are up in arms about racist caricatures of ourselves, let’s also address our own group’s pervasive, lunatic, and ugly views surrounding dark skin: one that has accompanied us throughout our history, and walked easily onto the stage of the present moment, like a conjoined twin we mostly pretend isn’t there.

The Commonwealth Book Prize Shortlist

The Commonwealth Book Prize has just announced its shortlist. (Diarise: regional winners to be announced 22 May and overall winner on 8 June.) It promises to be a wonderful, wonderful collection of novels; and I’m excited to read many on this list over the summer. What does this list illustrate? At the risk of being knocked over the head for being a harbinger of re-hashed postcolonial critique, I’m still going to say it: does the Commonwealth Other consist solely of (largely white) South Africans and Indians, with a smattering from elsewhere (including a Zambian: yeay!; a Sri Lankan: a shoutout to the ancestors!; and a Pakistani)?

While I’m truly appreciative of the work that these writers have done, and have no criticism of the fact that their work is deserving of nomination, such a India-South Africa heavy contingent makes me wonder about the reasons why people from other Commonwealth nations do not appear with the same frequency. The list hints heavily of the British colonial mission in South Africa and India, and how the subjects there — British transplants to those locations, or ‘native’ inhabitants — were shaped as colonial subjects. The continued dominance of a certain segment of the population of India and South Africa on British prize lists simply reflects that history’s hand on the present moment: those who were already constructed (by the Crown and the Raj) continue to have access to the power that Britain wields, and we continue to value what the British regard as their prize possessions.

* And the South African Books LIVE blog reminded its readers that Shelley Harris, the author of the novel ‘Jubilee’, doesn’t even identify as South African — she describes herself as “completely and happily British” — while another South African writer who lives in France, Denis Hirson, the author of ‘The Dancing and the Death on Lemon Street’, was shortlisted in the Canada and Europe category.

Art and assassination in Angola

Benguela-based human rights group, OMUNGA, attracted international attention last year when it sponsored an international festival of urban art and culture. Organized by a group of Angolan artists and social activists, “Okupapala” was launched as an effort to create visible, collaborative responses to socio-political exclusion. This week, OMUNGA responded to the assassination of one of their volunteers in Catumbela. Their published statement (here in Portuguese) is brief:

On April 24th 2012 JÚLIO SANTOS KUSSEMA died after being shot in the head by three bullets at approximately 11 pm in the municipality of Catumbela, where he was working at a small establishment. He was killed by non-identified persons. Júlio Santos Kussema was born in Lobito and lived in Bairro da Luz. He graduated with a degree in business administration from the Universidade Lusíada and volunteered with OMUNGA as an IT facilitator between 2007 and 2009. OMUNGA is shocked by this event but has found no association between the murder and the ties Kussema has maintained with OMUNGA. OMUNGA take this opportunity to once again extend condolences to the bereaved family and to urge the National Police to continue with appropriate investigations.

Their first annual festival went off in November 2011. The line-up was impressive. Artists and other thinkers from Argentina, Brazil, Cape Verde, Colombia, Cuba, France, Guatemala, Italy and Portugal joined Angolan artists in Benguela, Lobito and Luanda. They organized lectures, workshops, theater and musical performances. Yes, French artists wanted to do “Afro” and “urban tribal dance”. (See the list of venues under “locais do evento.”)

Okupapala’s work has struck a nerve among government officials, who have responded with panic. Throughout 2011, they routinely canceled or disrupted public events at the last minute. Questionable police action was documented by Front Line Defenders in English and archived by OMUNGA here. Ongoing harassment is available in more detail in Portuguese (in different parts: one, two, and three).

Angolan rappers and other visible protesters have continued to face police intimidation and alarming levels of state violence this spring (see coverage in our archives and this in-depth feature on Al Jazeera).

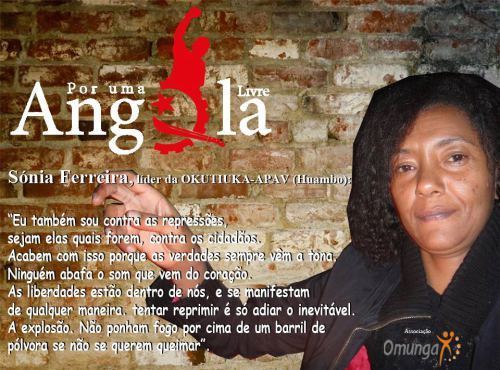

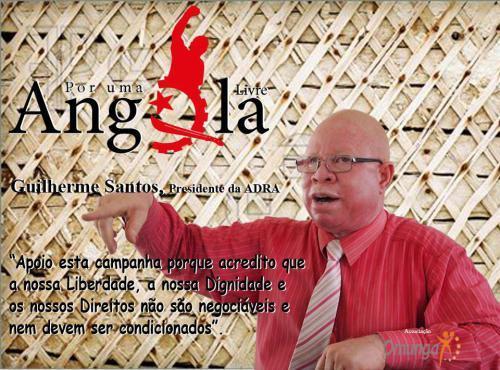

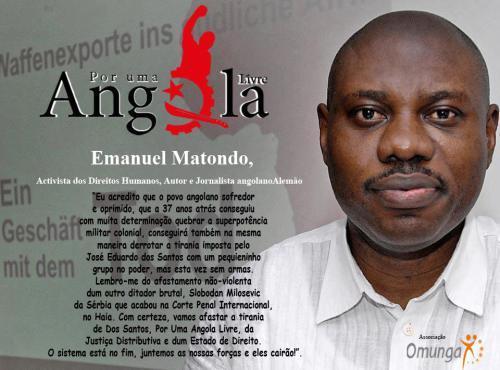

In the past weeks I’ve asked organizers how this violent pushback has changed the way they think about establishing and maintaining public platforms. Organizer José Patrocínio stresses the importance of their new coalition building within the ‘Por Uma Angola Livre’ (For a Free Angola) campaign against the prohibition, repression, and criminalization of demonstrations. As far as creative intervention goes, members joining ‘Por Uma Angola Livre’ offer public images that play with the authoritative poses of government officials.

Okupapala members call for international participation and cultivate space where local artists can talk about what it is like to live under the threat of dispossession and displacement. They describe themselves as play fighters; playing as discovery, experimentation, pleasure and change.

One woman challenged graffiti artists to make something beautiful in her home. Such a challenge puts a good twist on the twentieth century conviction that the personal is political, and claims a public sphere that extends everywhere it has not been officially defined. Okupapala ‘took over her house and sprinkled it with imagination.’

To be continued.

May 3, 2012

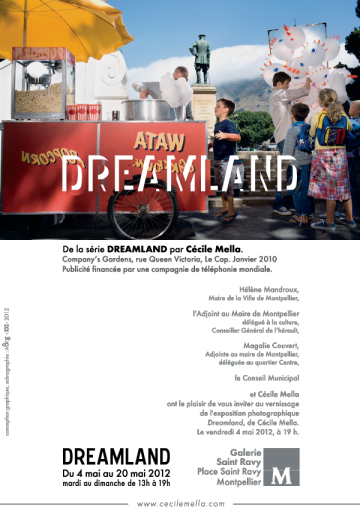

Exhibition. Cape Town in France

Cécile Mella (remember her portraits of the Cape Town ad world) will be showing her photography series ‘Dreamland’ in Montpellier, France this month (at the Galerie Saint Ravy). Come through if you’re in the area.

Not the Caine Prize

Since 2004, Le Salon africain (part of the annual Geneva Book Fair) awards the Ahmadou Kourouma Prize to an ‘African oeuvre, essay or fiction that reflects the spirit of independence and creativity which is the heritage of [Ivorian novelist] Ahmadou Kourouma’. This year the Prize goes to Rwandan author Scholastique Mukasonga for her latest novel ‘Notre-Dame du Nil’. Of the past 8 winning books, not one is available in English:

2011 Photo de groupe au bord du fleuve (Emmanuel Dongala)

2010 Si la cour du mouton est sale, ce n’est pas au porc de le dire (Florent Couao-Zotti)

2009 Solo d’un revenant (Kossi Efoui)

2008 Le Bal des princes (Nimrod)

2007 Le paradis des chiots (Sami Tchak)

2006 Babyface (Koffi Kwahulé)

2005 Matins de couvre-feu (Tanella Boni)

2004 Survivantes, Rwanda 10 ans après (Esther Mujawayo & Souad Belhaddad)

In a recent profile of French-Congolese (RC) author Alain Mabanckou, the L.A. Times blames “the parochial tastes and pinched profit margins of the U.S. publishing industry [for] hav[ing] restricted Mabanckou’s visibility on U.S. bookshelves”. I can’t think of any other reason why these 9 Prize-winning works haven’t yet been translated. By not doing so, the Anglophone publishers are keeping their readers from accessing a Francophone world of imagination that spans more than a quarter of the African continent — not to mention the Francophone diaspora. Don’t tell me there’s no interest.

May 2, 2012

Patricia Asero Ochieng’s argument

Remember “Silence = Death”? There’s more. Withholding = Death. Withholding necessary funds. Withholding lifesaving medications. Withholding life. In Nairobi last week, Patricia Asero Ochieng, Lucy Ghati, and Rose Kaberia joined Maureen and Anyango and many others to raise a ruckus about the trickle of Pepfar funding for people in Kenya living with AIDS. In particular, they were raising their voices, placards and fists over $500 million dollars allocated but not yet spent for antiretroviral medications. That’s a lot of money, drugs, and lost lives. And of course all the major agencies blame all the other major agencies. US officials argue it’s Kenyan ministerial inefficiencies. Kenyan officials take one of two lines: it’s US processes, or, it’s all fine and you’re overreacting.

Those living with AIDS, such as Patricia Asero Ochieng, know better. They know that all the agencies are guilty of squandering time, money, lives. They know that neither the US government nor the Kenyan government nor any of their proxies has ever really addressed the stigma, has never really addressed the toxic nexus of poverty and health and illness, has never ever really listened to the people or communities living with HIV and AIDS.

Women like Patricia Asero Ochieng know about the guilt, and they know that the only way forward is organizing and standing up to the powerful. Talking truth to power may be important, but organizing a counter-power equal to and greater than the ruling power … that’s the ticket.

Patricia Asero Ochieng has been demonstrating that wisdom for years. She was the named plaintiff in 2009, in something called Petition No. 409. In 2008, Patricia Asero Ochieng saw new legislation about intellectual property rights and counterfeit drugs. She looked into it and realized that much of the discussion was actually about generic drugs, and she knew that her access and the access of all the women, children, men in Kenya, and beyond them across the continent and the world, was under threat. So, Patricia Asero Ochieng and two others, Maurine Atieno and Josephy Munyi, took the State to court. They were joined by the local AIDS Law Project, directed by Jacinta Nyachae. Arguments were made in courts and arguments were made in the streets, homes and hallways of Kenya.

Patricia Asero Ochieng’s argument was direct and powerful: the Kenyan Constitution protects the right to life, dignity, and health of people above all else. In particular, above the ‘right’ to protection for intellectual property. For three years, Patricia Asero Ochieng and her colleagues waited and organized, all the while arguing that this is a civil rights issue, a human rights issue, a women’s rights issue. Women’s rights both because of the number of women in Kenya living with AIDS and because of the centrality of women to the pandemic, from mother-to-child transmission to primary caretakers of extended, and often devastated, households and communities.

Justice Roseline Wendoh effectively agreed, and, in April of 2010 stopped implementation of the law with respect to the generic case. Then it sat until April 20, 2012, when High Court Judge Mumbi Ngugi concurred with the earlier ruling, the core of which is:

The right to life, dignity and health of people like the petitioners who are infected with the HIV virus cannot be secured by a vague proviso in a situation where those charged with the responsibility of enforcement of the law may not have a clear understanding of the difference between generic and counterfeit medicine. The primary concern of the respondent should be the interests of the petitioners and others infected with HIV/AIDS to whom it owes the duty to ensure access to appropriate health care and essential medicines. It would be in violation of the state’s obligations to the petitioners with respect to their right to life and health to have included in legislation ambiguous provisions subject to the interpretation of intellectual property holders and customs officials when such provisions relate to access to medicines essential for the petitioners’ survival. There can be no room for ambiguity where the right to health and life of the petitioners and the many other Kenyans who are affected by HIV/AIDS are at stake.

There can be no room for ambiguity when the right to health and life are at stake. Two weeks later, when representatives of the US and Kenyan government were meeting in one of the poshest hotels in central Nairobi, you know who was outside, singing, dancing, shouting, and raising a ruckus? Patricia Asero Ochieng, and all the women and men in Kenya who know and teach … there can be no room for ambiguity.

May 1, 2012

Documentary–’I am Malawi’

‘I am Malawi’ is a short documentary by Geert Veuskens and Pieter de Vos. (Part 1 above, part 2 below.) Veuskens gave us some more details about their project:

We shot the images for the documentary in May-June 2010 in and around Lilongwe. Working with artists like Mandela ’3rd Eye’ Mwanza, Dominic ‘Dominant 1′ Sangalakula, Qabaniso ‘Q’ Malewezi, Peter Mawanga, Waliko Makhala and Lucius Banda, this film aims to tell a story about identity, ‘pride’ and uprising in a globalized world. Although ‘pride’ is a word that I don’t like all that much, I don’t really have an alternative for it either. It is suggested in the film, but it mainly refers to the dependence on foreign aid and to the awareness of the people I worked with that historically many things have happened that created a personal discomfort they now try to break. In fact, the film is also structured in this way. The first part tells the story of how they perceive foreign aid and dependency. The second part tells how the artists search for ‘artistic’ solutions. Each in their own way. The artists, all from different backgrounds, talk about their country, their history and their search for an identity that can stand out in the global community.

While doing research for the film, we particularly looked on facebook for Malawian organizations focusing on media and art. Through these organizations, we got in touch with the artists. The story slowly began to take shape and we continued the conversation when we met up with them in Malawi. The artists we chose to feature are on the one hand people who sought for a style elsewhere (the hip-hop duo ‘Dominant 1′ and ’3rd Eye’) and, on the other hand, people that return to their cultural heritage, picking up traditional instruments again.

We wanted to work with these artists to achieve a concrete exchange of ideas, visions, identity, politics and culture.

Here’s part 2:

Also worth watching is the music video that comes with the documentary and another short video Veuskens created for and about ‘Rhythm Of Life’, a UK registered organization working in the Malawian music industry (“supporting and facilitating the growth of the creative industries”).

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers