Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 540

April 26, 2012

The ‘African Men–Hollywood stereotypes’ video, positive news and ‘Brand Africa’

As much as I tried, I can’t seem to like the new video by San Francisco-based NGO Mama Hope. Four young Kenyans sit on a bench talking through the worst stereotypical depictions of African men in Hollywood movies. We get to see these clips (which don’t not tell us much; the clips don’t make sense in the way they’re used here.) Watch it above. The surprising (!) catch is that our guys on the bench are all middle class, play rugby and are on Facebook. The video is by the same people who made ‘Alex Presents: Commando’ (that was cool just as a piece of popular culture) and the more earnest “Call Me Hope” (read Neelika’s generous critique). But this latest instalment – ‘African Men. Hollywood Stereotypes’ – isn’t funny (except for the line about a shirtless Matthew McConaughey), feels forced, and won’t get anything like as many hits. But there are wider issues to think about too.

Some quick background. The idea with this campaign – titled ”Stop the Pity. Unlock the Potential” – is to tell “the story of connection instead of contrast and potential instead of poverty.” In Mama Hope’s own words: “People everywhere have talent and capacity, and people everywhere share a desire to be able to use those gifts to improve their lives and the lives of the people they care about.” As Neelika pointed out in her post on “Call Me Hope”, there’s a sentimentality and feel good quality to it.

But back to “African Men. Hollywood Stereotypes”. There’s a way in which this is part of the “Brand Africa” and lets-have-more-positive-coverage-of-Africa discourse that’s all the rage now.

Sure, the Western media continues shamelessly to traffic in vicious stereotypes of black African masculinity drawn from the deep histories of racist iconography that remain at their disposal in spite of (more likely under the cover of) the general subscription to a rigid politically correct consensus. Yes, it would be nice if they would give this a rest once every few centuries.

But do we really need this kind of “positive image for Africa” stuff? At best it can be framed as a necessary corrective, but the whole PR “brand Africa” shtick is boring, patronising, and finally insubstantial in its attempt to transform the West’s time-honoured way of imagining the continent, ideas that are thoroughly tangled up with ingrained – and much beloved – supremacist notions of Euro-American culture and identity. This isn’t all going to go away because you pointed out that there’s a bloke in Nairobi called Brian who works in HR.

Lydia Polgreen was right last week when she tweeted about Afua Hirsch’s take on lazy Western reporting in/of Africa in the Guardian. (All the big print beasts seem to be bringing out new versions of this kind of post/op-ed every day, which is welcome, though some of the more recent critiques have simply rehashed a lot of not especially original arguments, and even headlines.) To quote Polgreen:

What is more insulting than the idea of “positive news” from Africa? As if the continent was a dull witted child in need of encouragement.

That was pretty much the vibe I got from the ‘African Men’ video. “I am an African man,” all four guys say, at which point I was really hoping one of them would add: “And I also speak English. Fluently. As such I won’t be needing the ginormous subtitles you’ve slapped underneath my actually-totally-comprehensible Kenyan accent.” (The BBC once subtitled everything that Professor Felix Chami, an archaeologist at the University of Dar es Salaam, told Gus Casely-Hayford when he was interviewing him for that Lost Kingdoms of Africa series on the BBC. At least no-one is spared.)

People might want to see this video as a counterpoint to Kony2012, and it’s of course nothing like as egregious, but I’m not sure exactly how far we can move away from the Invisible Children with a video by Joe Sabia (who directs the Mama Hope stuff). Sabia is another Silicone Valley, TED-talking master of viral narrative, which seems to boil down to not much more than a heavily concentrated dose of American sentimentality, however that sentiment is directed. Mama Hope is another white-staffed NGO run out of California. They are doing something very different by attempting to engage very broad cultural currents (as opposed to, say, organising the world’s most self-congratulatory wild-goose chase in Central African Republic), but that’s not without its problems.

The strongest line in the video by far is “There is nothing more dangerous than a brave Western protagonist”. It’s an incisive claim because the stereotypes that they’re trying to challenge have never been meaningful descriptions of African masculinity itself, but have always been ways of constituting an elevated set of ideas about whiteness. It is not incumbent upon African men to prove their normality to Gawker readers by being filmed by a Western NGO doing unthreatening, “modern”, capitalist things like joining Facebook, playing rugby, living in a city, having friends, doing an office job and so on – and that’s why the staging of this whole thing feels a bit weird.

“Stop the pity. Unlock the potential.” It reads like the headline on some dumb Economist editorial about emerging markets: It’s time to end racism, guys, there’s money to be made. (By the way, what is this obsession with proving Africa has a middle class?)

And that’s the thing about branding the continent of Africa in a positive way. “Positive” or not, the chances are you’re selling something that isn’t yours to sell.

Classic African Films N°2: ‘Touki Bouki’ by Djibril Diop Mambéty

This is, perhaps, one of my favorite films of all time. A shifting and fragmentary tale of two young lovers — Mory and Anta — and their attempts to flee Senegal for Paris, ‘Touki Bouki’ is Djibril Diop Mambéty’s masterpiece. It fizzles with wit and acuity, it diagnoses the ambivalence toward the colonial master and the at times surreal practices of ‘traditional’ culture.

My reading of the film is undoubtedly influenced by the following quote, a manifesto of sorts, from Mambéty:

“The word griot…is the word for what I do and the role that the filmmaker has in society…the griot is a messenger of one’s time, a visionary and the creator of the future.”

In comparing himself to the traditional storyteller figure in West African society, Mambéty bridges the divide between what was considered ‘traditional’ and modern, defying the colonial logic desiring to cast the native population as inherently anti-technological. In his comparison, Mambéty invokes the fragmentary, questioning narrative — deeply embedded within aural traditions — and fuses his filmic sensibility with this social practice. As a result, many Western critics argued that Mambéty’s films were ‘poorly constructed’ (see e.g. Melissa Thackway, Africa Shoots Back, 2003, p.78), but this digressive narrative style can be observed in Mambéty’s ‘Le Franc’ (1994), Med Hondo’s ‘Soleil O’ (1969) or Sissako’s ‘Octobre’ (1991), all of whom employ a challenging structure which can be traced to a style of oral storytelling.

What this narrative style does is provide an insight into the value of a people and their social structure (through Mory and Anta, we are shown how the status quo of Senegalese society is negotiated by a younger generation), while using traditional means to diagnose a contemporary reading of the present. It’s a flow of exchange between old and new, a negotiation, perhaps perfectly embodied in Mory’s motorbike — a slick piece of machinery adorned with the horns of a bull. But, it is also important to note that while I’m tracing a symmetry between the griot style of storytelling and orality ‘at work’ in Mambéty’s filmmaking, I’m not transposing one onto the other; it’s not the case that oral literature is inherently cinematic, but rather, that through negotiation one can empower the other.

An apt example of Mambéty’s style in ‘Touki Bouki’ is a sharp cut between a young boy (Mory) riding a bucking cow, accompanied by a soundtrack of glittering kora music, to — in a split second edit — an abattoir where bulls are being slaughtered, the screaming sound of animal terror tearing the viewer away from the previous tranquil scene. From the dreamy calm of a pastoral history, to the brutality of industry, mass production, ‘the market’, Mambéty’s edit is at once a critique of a nostalgia for Senegal’s ‘pure’ pastoral, pre-colonial past, and its (then) current position as part of the French Empire. This edit shows Mambéty’s penchant for discontinuity, for symbolism, and for a stultifying lyricism, perhaps I’d even go so far as to say a kind of percussive editing rhythm, as if perhaps Tony Allen were at the cutting table.

But further than just his narrative style, Mambéty seems to embody this position of a ‘modern’ griot, using contemporary modes of visual storytelling to further the narrative arts he was born into. And why not? His films are excellent examples of how the contemporary can be read through the (re)construction of myths and narratives from a collective memory — breathing life into the space occupied by a set of symbolic codes of both tradition and modernity, that through his films are rendered synchronous and simultaneous, a point Imruh Bakari makes brilliantly in the book ‘African Experiences of Cinema’. A notion of modernity, in this context, is powerfully wrenched from its Western stronghold, used instead to attest to what Bakari calls ‘the complex tonality of the African experience’.

So, while Mory and Anta trick and swindle their way closer to Paris, Mambéty tests certain situations and norms; he demonizes the ‘revolutionary’, he shows a gay character, he shows sex between two African people in a way rarely ever shown before; full of tenderness, eroticism, reclaiming love and intimacy from the stereotypes of Western presentation. Mory and Anta make love in the shadow of the motorbike, on the edge of a cliff. It’s a breathtaking scene, their impassioned gasps slowly drowned by the repetitive crashing of the waves.

Throughout the film they are intimately tied together. However, in the final moments when they finally board the boat to go to France, Mory is overwhelmed as he sees the horns of his motorbike, and runs back to land to find it. In doing so he abandons Anta to travel alone. Manthia Diawara notes that this is typical of the griot narrative, which flirts with change but ultimately restores order by returning to the traditional. Mory flees back to the medina (the slum), restoring him, and the narrative, back to tradition.

But Mambéty also subverts this unconditional return. Through his depiction of their dress and behavior, Mambéty demonstrates that the contemporary youth are multi-sited; when their actions denote one place, their dress reveals another place. Mambéty has therefore employed a typical griot narrative, but subverted it. Despite ultimately restoring the narrative to the blissful calm of the traditional herdsman scene that traverses the arid landscape of rural Senegal, Mambéty has consistently fused traditional symbols to modern modes of being, most strikingly in Mory’s motorbike.

* You can watch ‘Touki Bouki’ on Mubi (by signing up to their service — they have many fantastic films on their site), or you can watch it on The African Film Library for $5.

Africa and the state of Israel

My Land, a new documentary on the occupied territories of Palestine by Nabil Ayouch, opens with the statement by the director that his background gave rise to the inquiry his film makes. In the Israel-Palestine conflict this is almost a statement of the obvious: where you come from defines your position. Ayouch is one of the notable exceptions. The son of a Moroccan Muslim and a Jewish Tunisian, he claims a position of unusual sensitivity to the schizophrenic realities which trouble the region.

The film, which received its UK première this week as part of the fourteenth Palestinian Film Festival, comprises of interviews with the former inhabitants of three villages in the West Bank expelled by the Israeli army in 1948, and of interviews with the current occupiers. Here’s a fragment (with French subtitles; the documentary’s website has more):

An original gesture this documentary makes is to film the Israelis watching the interviews with the Palestinians who formerly inhabited the land they now claim as their own. No one is unmoved: some remain unrepentant, some lament their ignorance. Some argue for the desirability of co-inhabitation, some dismiss it as impossible.

These arguments are all familiar: this territory – rhetorical and real – has a fraught history. The questions are confrontational but never aggressive, and the film justifies its own making through a quiet persistence. The cinematography offers a pastoral vision of the Palestinian landscape, troubled by Israeli diggers on a seemingly interminable attempt to construct an indestructible justification, rugged scrubland, sparsely populated by farmhouses and elegantly supervised by birds. In contrast, no beauty is sought in the matter-of-fact images of the refugee settlements: interviews are shot in candlelight or in the indifferent haze of a strip-light.

One young Israeli woman speaks intelligently of her attachment to the area and moral disgust at the army, then says “I don’t feel guilty [about the Palestinians] I feel very close to them”. One of the striking facts this film establishes is a similarity of opinion over the landscape: the Israelis love it and the Palestinians love it too. Some of the Israeli settlers, with a cruel irony, describe the Palestinian longing for this land as an inability to ‘move on’. An old man says “I dream of going back … even for the last day of my life.”

One of the frustrations of this film is that this conflict remains totally Eurocentric – the film does not pursue narratives elsewhere, and Palestine is formulated as a state in which Europe invades the East. It would be interesting to see a filmmaker like Ayouch engage with the complexities of Africa’s relationship with Israel, a state where African Jews face racist discrimination.

Thanks to Nour Sacranie for suggesting the last point; look out for her forthcoming report on the festival over at ibraaz.

Among the other offerings of the festival, check out Mounir Fatmi’s The Beautiful Language, which stages an intervention in a classic film in order to explore the relationship between French and racism, and The Problem, which examines the Moroccan occupation of the Saharawi lands.

Yinka Shonibare’s National Treasure

The ever-well-informed African Art in London announced this week that Yinka Shonibare’s contribution to the fourth plinth of Trafalgar Square — Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle (2010) — has been bought for the nation after a successful campaign by National Maritime Museum and the Art Fund:

The artist calls a ship in a bottle ‘an object of wonder’ and this work has certainly captivated crowds, fast becoming a favourite among Londoners and visitors alike. In common with the original, it has 80 cannon and 37 sails set as on the day of battle. Materials include oak, hardwood, brass, twine and canvas. Its richly patterned textiles – used for the sails – are of course a departure from the original. These were inspired by Indonesian batik, mass-produced by Dutch traders and sold in West Africa. Today these designs are associated with African dress and identity. [Remember Neelika's post on the excitement about 'African fabric'.] In such ways, the piece celebrates the cultural richness and ethnic diversity of the United Kingdom, and also initiates conversations about this country’s past as a colonial power. (Art Fund)

Shonibare’s piece is undoubtedly one of the more interesting contributions to the plinth, a recent space for public art, and one proclaimed by the media as the most significant. I’m always unclear how much an artist, if they remain committed to structural change, should participate in these institutions, or accept institutional plaudits (Shonibare is an MBE). But it is reassuring that the nation has bought a treasure which signals such ambivalence about the status of the nation itself.

April 25, 2012

Guggenheim’s map–Where is the rest of Africa?

Guest Post by Jennifer Bajorek and Erin Haney

The recent announcement of the Guggenheim Foundation’s new “Guggenheim UBS MAP Global Art Initiative” bears all of the hallmarks of the present era. It is funded by a bank. It has the word “global” in its title. It claims explicitly to challenge “a Western-centric view of art history,” according to the Foundation’s director, Richard Armstrong, in a piece by Carol Vogel recently published in The New York Times. The project will mount this challenge by investing in series of linked-up residencies, exhibitions, acquisitions for the museum’s permanent collections, and public programming with artists, curators and educators in parts of the world hitherto largely ignored by the museum. The modus operandi is encouraging, particularly when compared with late-20th-century attempts to bring non-Western art into dialogue with institutions in the North. The list of regions is long, and includes South and Southeast Asia, Latin America, the Middle East and North Africa. One thing it is not, however, is global: Africa south of the Sahara, and thus 2/3 of the continent, has been excluded.

We were disappointed to discover this, but not entirely surprised. Africa is not the only omission (Central Asia and Australia are also missing), but it is the most conspicuous, and it casts doubt on the initiative’s stated aim of challenging “Western-centric” views. How can such a large and dynamic part of the world remain invisible—must it remain invisible—in the midst of this rapidly shifting institutional landscape? Given the efflorescence of exciting new initiatives in Africa, doesn’t a map that leaves most of the continent out start to look rather retrogressive?

Many reasons for the exclusion of most of Africa from this and other “global” initiatives are not difficult to divine. They are connected with the motivations of banks and bankers, and, by extension, wealthy patrons, collectors, and dealers, whose relationships to the museum world have always been shaped by broader economic trends. We have already grown accustomed to the idea of a Guggenheim Abu Dhabi (or, closer to home, the BMW Guggenheim Lab). Money from the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and more recently, a handful of countries in North Africa has created new flows, deepening collections in European and North American museums for some time. And no one, at least not anyone with any practical experience of fundraising, is going to criticize a museum or other arts institution for adapting its agendas, un tant soit peu, to fit those of its financial backers.

Yet the concentrations of wealth that are connected with both museum boards and the high-ticket art sales that the art market chases—and that are associated, precisely, with a Swiss bank’s clients—are few and far between in Africa. South of the Sahara, they can be found with critical mass primarily in South Africa, Angola, DRC, and Nigeria, where they remain closely tied to the oil, diamond, and other mining industries and, in South Africa in particular, the power of white elites. It seems a safe assumption that no American museum would be content to forge a “global” partnership with African artists, curators, and institutions that was brokered exclusively by white South Africans, or that showcased work by white South African artists—although some have come perilously close. We recognize just how difficult these negotiations are. But surely these are the very negotiations that those wanting to cultivate “global art” as a category should be embracing rather than shying from?

This brings us to a second point. Rather than simply lamenting the conservatism of the museum world, or throwing up our hands at the narrowness of vision exemplified by programming that moves in lockstep with “global” capital, we would, above all, urge our colleagues at the Guggenheim and elsewhere in the American museum world to consider the opportunities they are losing when they leave most of Africa off their map, and to reflect more seriously on whether, and where, art institutions have room to challenge the status quo.

When one considers the contemporary art scene in Africa, the lost opportunities are extraordinary. In our own recent writing about art institutions on the continent, which has focused on photography, we have underscored the intensity of the creative scenes in many African cities, where, thanks to the inspired efforts of a rising generation of artists and activist curators, new institutions and initiatives are popping up daily. If one sticks to photography as a test case, there is a richness and diversity of events, projects, and platforms emerging that cannot be confined to a single city or country. Beyond Bamako, whose photography biennial has been a growing favorite with European curators since 1994, Harare and Cape Town both host exciting annual photography festivals. Dakar and Abidjan have both been important hubs for more transitory, but no less important, activity. Most recently, Addis Foto Fest, in Addis Ababa, has been added to the roster of influential gatherings, where photographers, artists, and curators meet to enter into precisely the kind of transnational and cross-cultural dialogue that the Guggenheim initiative, and others like it, want to invite. Cairo, Johannesburg, and Algiers are characterized by their own varied and thriving art scenes, which include inventive photographic scenes. In a moment that valorizes flow and the expansion of transnational networks, the interconnectedness of these cities with others on the continent is particularly crucial to note. This is one of many reasons for not subscribing to the North Africa/sub-Saharan Africa fracture, a legacy of both European colonization and racial ideologies. Linked to Algiers, through a series of artist-led exchanges, is Lubumbashi, where a promising photography festival has established itself.

It is instructive to contrast the Guggenheim’s approach with that of another recent initiative, which has placed a premium on African inclusion. In October of last year, a Nigerian bank, Guaranty Trust Bank, entered into an intriguing partnership with Tate Modern, which has created, and funded, a curatorial post (Curator International Art), a comprehensive acquisitions remit, and related programming dedicated entirely to increasing the presence of contemporary African art in that museum. Like Guggenheim/UBS Wealth Management, the Tate Modern/Guaranty Trust partnership has been imagined on a model of institutional networking and “knowledge exchange,” which is now very fashionable. Significant in the case of Tate was the appointment of a new curator (Curator International Art), who, according to the press release, will work not only to bring African art into Tate’s galleries in London, but also to “to broaden Tate’s international reach in Africa.” It is too soon to tell what will come of this initiative. But we find it promising that the new curator, Elvira Dyangani Ose, has focused on artists’ collectives—an increasingly hot topic that is, in fact, directly relevant to Africa, as Holland Cotter underscored in an article that appeared in the Times on Sunday (April 15, 2012). Indeed, Dyangani is the artistic director of the 2012 edition of the above-mentioned festival in Lubumbashi, where collectives have played an extremely significant role. Not only have collectives been of immense historic importance on the continent, but a new generation of artists is privileging the collective in order to ask its own questions about mapping, or re-mapping, the terrain of “global art” in the 21st century from a unique vantage point.

What we admire about so many of these initiatives that we and our colleagues are following in Africa is precisely that they have taken it upon themselves to analyze, query, and challenge “Western-centric” views of art practice and art history. Beyond this, they are challenging all of us to think more carefully about what is lost when the term “global” is selectively deployed to refer to the movement of capital rather than of creative energy or ideas. To miss out on the energy, and ideas, that are swirling around these initiatives in Africa, in a program that announces itself under the banner of breaking down barriers and expanding knowledge, would be at best a provincial move.

* The authors are writers, researchers, and independent curators who collaborate on projects with artists, photographers, and related institutions in Africa.

Shameless Self-Promotion: Chief Boima’s Many Identities

If you’re unfamiliar with my musical work, OkayAfrica.com recently did a profile on me for their web TV series.

Meanwhile, a team of fellow African DJs in New York and I have linked up to try and establish a permanent home for people of all backgrounds to enjoy the young, fresh, creative sounds coming out of the diaspora at large in downtown Manhattan. This Friday at Bamboo in Manhattan’s East Village we present the second edition of a night we’re calling PAN. Joining us will be DJ Marco, the owner of San Francisco’s Baobab Village, and the crew from Andrew Dosunmu’s Restless City who will be celebrating their theatrical premiere. Hopefully the night will also serve as a celebration of independence and freedom for all the local Sierra Leoneans and South Africans. Here’s the poster:

April 24, 2012

Makode Linde–the ‘Swedish Cake’ artist–explains himself

“It’s a self-portrait. It’s not meant to represent anything, except me.” Makode Linde seems more bemused than irritated when we discuss the huge, worldwide storm that his cake has stirred. “People are talking about this in Africa, in South America,” he says, “there are so many different interpretations of what it means, and I don’t want to take away any of that. But it also really seems to have driven all the trolls out of the woodwork.” Strange to think that before last weekend, it was just another Afromantic.

Afromantics’ is Makode Linde’s line of artworks that use the blackface figure that has now become so infamous. The name, he says, reflects on the romanticized, supposedly positive stereotype of the happy, grinning ‘pickaninny’ (a caricature of black children) that appears on all the artworks, and is meant to show the connection between those stereotypes and the more vicious ones, all connected in the same system of oppression.

Each Afromantic is based on taking an item from Eurocentric art or popular culture and painting stereotypical blackface on top of it. “The outlines, the specific features of the faces of these items are completely obscured,” Makode Linde says, “their character is completely removed, and they have this new, supposedly ‘African’ character imposed on them.” It’s an almost painfully symbolic reproduction of the process of Othering, diverse individuals being forcibly assigned a simplistic shared identity.

When Pontus Raud of the Swedish Artists’ Organisation called in asking for the cake, Makode knew he wanted to make it an Afromantic. (Though he did briefly toy with the idea of making a chocolate Naomi Campbell.) Since the cake was to go on display in a museum, he wanted to work with something from the Eurocentric discipline of Art History, and so chose the body of the ultimate canonical classic, Venus from Willendorf, the supposed origin of a story that has always excluded African or African-bodied voices. (An accusation subtly imparted by the painted blackface.) The faceless Venus was also ideal to paint in the stereotypical looks of the Afromantic series, and to make the work more brutal and more relational he included himself as the head.

Marianne Lindberg De Geer took the picture that made the cake known, worldwide. She is also an artist, one of Sweden’s best known, and like Makode Linde’s, her work is based on identity and identification, the experience of being Othered, in her case as a woman. (In one recurring work, both like and fundamentally unlike Makode Linde, she enters into the experience of others by painting her own face over stereotypical depictions.) She knew something was about to happen, and readied her camera, pushing herself through the crowd. When the Culture minister started cutting the cake, she snapped “perhaps 25 or 30” pictures, and caught the second time the minister leans over to feed the artist, “like a mother feeding a crying child.”

“It all happened so quickly. It was horrifying, so aggressive, the scream,” Marianne Lindberg De Geer says. And for almost an hour, Makode Linde screams and screams as person after person cuts into the cake. People laugh. Some react negatively and back away. Some try to check if Makode Linde is okay, lying there in his cramped box. Some cut with happy abandon. Everyone seems to have a different reaction in the room. But no-one tried to stop it. “We were all complicit,” Marianne Lindberg De Geer says.

Me too, snapping away. We were all assured that it was alright, that it was art, that this was part of the performance. It was like the Milgram electric shock experiment, no-one stepped in to prevent the simulated pain from happening. I think it was a very good work of art. I feel I should probably apologise to Makode for ruining his work by spreading that picture.

The idea that it was a conspiracy meant to trap the Culture minister, as we first suggested in our first take on Linde’s performance, can probably be abandoned. None of the people I speak to–Makode Linde, Marianne Lindberg De Geer or organiser Pontus Raud–claim they knew what the other parties were going to do. Marianne Lindberg De Geer does say, though, that she probably wouldn’t have sold the picture if it hadn’t been the intensely disliked, neo-liberal Culture minister in it. “She has tried to force us all into becoming entrepreneurs,” Marianne Lindberg De Geer says, “so I decided to try to boost my income as a freelancer at her expense.”

Lying in the box was extremely uncomfortable for Makode Linde. Both physically and emotionally. “It was an experience of total objectification,” he says.

Imagine people standing half a metre from your head and talking about you as if you weren’t there. As a relational artwork, it was an artistic experience for me too.

It’s something he has experimented with before.

For a party that was also a relational performance last year, he painted twenty of his friends in blackface, and charted their reactions during the party and afterwards, when many had drunkenly forgotten their make-up and were surprised at random strangers attacking them in the street. Everyone’s experience of being inside the blackface (he describes it as if it were a shell, an item of clothing) was different, and in a way it was an artwork directed at them.

They got to experience race in a way they hadn’t before. And the aim was also to get them to experience what it’s like being Makode Linde. All of the Afromantics, whatever you think of it, are to a certain extent his self-portrait.

People always want to put me in a box. I’ve got a white mother and an African father. Whites always think of me as black. Blacks seem to always think of me as white. The media calls me Afro-Swedish, but I didn’t know what that was until last week! People seem to have trouble with the idea that you can identify with traits of both black and white, and with both male and female gender roles. There’s this categorization that frustrates me incredibly.

When I mention that he’s being accused of not being in conversation with the African diaspora, of only talking to whites, he replies:

Well, I am white. [Long pause.] And black. But I seem to have to be constructed as one of two. I don’t talk about black experience, I don’t know very much about what the ‘genuine African’ experience, in quotations, is like. I’ve grown up in the privileged inner city. What is my supposed group? Inner city mulattoes? They’re a handful. I’m not joking when I say I know them all … and they support me!

“One reason I do this,” Makode Linde adds, “is because there’s no obvious correspondence between who I am and what people think I’m supposed to be.” Thus the focus on the stereotypes, on what he talks about as “the prejudice cloud”: a collection of traits his supposed blackness, that he doesn’t feel he shares, is meant to impart upon him. That includes the blackface, the idea of “rhythm in the blood”… traits that “his race” are supposed to have in common. “And one thing no-one has mentioned about the cake,” he says, “are the neck rings. They’re not even African, they’re Burmese! And yet they just get assumed as an ‘African thing’. They’re part of the prejudice cloud too, people don’t reflect. I’ve got nothing to do with these things, nothing, and yet people expect me to relate to them.”

That, too, was the reason female genital mutilation (FGM) became part of the cake. Someone brought up the angle when they discussed the fact that the cake was to be cut up, and Makode Linde jumped on it. “It’s another part of the prejudice cloud. The idea of savages mutilating their own people.” And yet, it’s become the focus of so much of the debate surrounding the piece. “The media asks me what I think of FGM,” Makode Linde says, “what am I supposed to say? I’m against it, I tell them of course.” And suddenly it has become the aim of the artwork.

Perhaps that’s unfortunate. There is what seems to be a highly legitimate feminist critique of the piece, focused on the symbolic cutting-up of the woman and the voicelessness of female African artists, that gets wrapped up in a wider discussion about the construction of FGM that Makode Linde seems to know or care little about. The Kenyan artist Shailja Patel’s much circulated article, for instance, has many valid points, but there’s a definite sense that she and the artist are speaking at complete cross purposes. I pose the questions that Shailja Patel, in her piece at Pambazuka News, derived from theorist Jiwon Chung, to Makode Linde and his replies are probably illustrative of this:

Cui bono? Who benefits?

“The debate benefits! If female genital mutilation is the topic that should be discussed, well, it seems to have been brought up a lot. Look at Google Trends, the search volume has increased steadily since the debate started.”

How do those whose suffering / body / experience is depicted feel? Do they feel they’ve been done justice?

“The experience depicted is mine, and I do.”

Are you speaking for them (because you have a voice, and they don’t), or are they speaking for you, because what they have to say is so much more compelling than you?

“I speak for myself. Who am I supposed to speak for? I don’t represent anyone. I think the idea that an entire group that I supposedly belong to speaks with the same voice is kind of racist, too. It’s ironic that supposed anti-racists seem to be lumping people together like this.”

Are you attributing clearly (giving clear credit)?

“I’m not. I thought art was supposed to be speaking for itself. Someone on Facebook thought I should put in a disclaimer, explaining the history of blackface and why I use it, but I think if people were really interested in my art they’d think it out anyway.”

Are you dialectical?

“Look, I’ve made over 40 interviews since this thing happened. I’ve never talked about my art this much before.”

Is your ‘I’ a ‘we’? Is your ‘we’ an ‘I’?

“No. My I is an I.”

If their suffering were to disappear, would you be truly happy? Or would you have to look for something else onto which to glom your dissatisfaction?

“I think it’d be fantastic if all of these stereotypes, this prejudice cloud disappeared. If this sort of thing could be presented, and no-one would even get the reference…then I could concentrate on making music.”

Do you belong, do you truly claim solidarity with the suffering — or do you do it only when it fits in with your concerns and schedule? How do you support them outside your art?

“If there’s anything I don’t tolerate, it’s racism and homophobia. My whole life I’ve been constantly a victim of racism, homophobia and transphobia. It doesn’t seem to matter how I define myself, people always do it for me. The types of categorisation, the types of attacks, seem to be the same, no matter what kind of prejudice.”

It’s as if both Makode Linde and his feminist critics are speaking the same language of power, stereotype, intersectional oppression, and yet they don’t seem to be connecting at all. For instance, when Makode Linde raises an issue with the way anti-racism groups act, it’s one that feminists often raise too and that would be right at home in one of the articles:

I realise it’s difficult to speak without resorting to categories like ‘black’, ‘white’, ‘male’ and ‘female’. It may be difficult to demonstrate oppression without them. But at the same it’s so close-minded not to realize that placing people against their wishes in these categories is the same sort of valuation process racists use. Let people define themselves as they like. If I say I’m a white woman, let me be.

It’s no surprise Marianne Lindberg De Geer, who is one of Sweden’s most famous feminist artists, talks along a similar track.

The more I work with identity and identification, the more I realise that people are essentially the same, that you can identify across groups. I think it’s fantastic that Makode as a man takes on the role of a woman in this way, I don’t see the problem at all. Makode is an Other too.

(He really is, in multiple, intersecting ways. You should listen to him talk about having dreadlocks and meeting homophobic Rastas.)

The peculiar context of Sweden’s race relations is another thing that seems to strike a wedge between Makode Linde and his international critics. As several articles rightly point out, the reaction would have been considerably different had the cake gone on display in the United States for example. Some would argue that a nostalgic understanding of their own White goodness makes Swedes blind to racism (hence the audience response), but Makode Linde has another take, too:

We don’t have the same history here in Sweden of slavery, of colonialist oppression. Our colonies were barely there. We don’t have the ‘guilt quilt’ big colonialist nations have, and yet we’re constantly asked to relate to the same issues of slavery and segregation that, say, the United States does. It’s as if our race relations are imported from the US, and the whole issue becomes almost a meta- or quasi-discussion.

Perhaps this is the reason blackface passes with less resistance in Sweden. But it’s probably also the reason that institutions that think of themselves as non-racist don’t deal with their own prejudice, because the general image is that Sweden doesn’t have much racism. And yet, looking at the actual situation, there’s staggering discrimination in healthcare, schools, in the justice system, in the labour market. And in higher education, as brought home with characteristic irony by Makode Linde in another of his artworks, where he comments on exposure, class and the over-representation of white students at the University College of Arts, Crafts and Design by baking oat balls in different colours.

He staged it at the school, and people laughed, until laughter “got stuck in their throats” once the realisation set in. “I think it’s a very Swedish approach,” says Makode Linde. “And a very effective one. Here it’s always been considered strange to take yourself completely seriously. Gays and Jewish people, too, have been using humour about racism and homophobia as a defense mechanism for a long time. In stand-up comedy, the sort of thing I do would pass unnoticed. Yet in the art world, joking about certain things is considered taboo, even if the intent is not racist. If there’s any problem I have with justice movements, it’s their lack of this sense of humour.” That, too, is perhaps an aspect of the cake that translates less well.

And yet Makode Linde has relished the debate and the different angles it has brought up. “People have so many interesting points of view on this,” he says. “The debate really seems to have benefitted, and even stuff like other videos of mine and other artists working on similar themes have been given a boost. That’s why I don’t buy the argument that I’m silencing other artists, it’s not like there’s one-–sorry for this one!-–attention cake that I’ve taken too large a chunk out of.” And he intends to keep working with the same themes, and the new things raised by the cake: “I’m following it all closely. And as a free artist I reserve the right to reinterpret my work and spin off new things in the future.”

* Johan Palme blogs as Birdseeding.

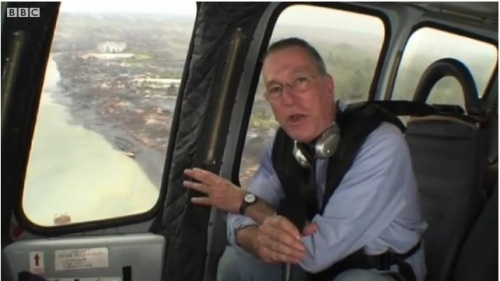

A BBC Report: “Shell brought me here …”

In a video posted today on BBC News, the BBC’s International Development Correspondent Mark Doyle is shown in a helicopter, bullet proof vest atop of the foreign correspondent’s uniform–the baby-blue shirt, ‘flying low’ over what Doyle describes as ‘possibly the largest crime scene in the world’. Invited by Shell, and accompanied by some of its engineers, Doyle is flown over pipelines in Southern Nigeria where evidence of local siphoning is clear; home-made refining pits that Doyle describes as ‘cauldrons’ (without irony), and thick black smoke are visible from the aerial images. Doyle repeatedly uses the words ‘illegal’, ‘stealing’ and ‘hacking’, while offering almost no context as to why the locals are reclaiming some of the resources.

The only explanation — ‘the people here are poor’, and of course, invoking the easy stereotype of Nigerian politics- corruption; “the suspicion is that there are some quite senior politicians who are involved in this illegal activity.” Doyle does also makes reference to the fact that while oil is being sucked from these areas, very little money is being put back into the local communities, but this point gets no further explanation at all. But of course, being on the invitation of Shell, Doyle wasn’t about to extend his context any further, only briefly admitting at the very end of the report, that while the locals are creating pollution, yes, Shell admits, their activity causes pollution too. It’s a shocking neutered piece of reporting on an issue that is so clearly generated and exacerbated by the relentless and irresponsible activities by multinational companies in Nigeria. It’s all the more shocking, given that less than 24 hours ago, The Guardian and many other newspapers reported that the huge spill in the Niger Delta in 2008, was ’60 times greater’ than the amounts claimed by Shell at the time, according to documents obtained by Amnesty International.

This BBC news piece is shamefully biased and propped up by Shell’s need to deflect attention, to try and present the local Nigerian population as ‘the problem’. All this, while they face legal action from 11 000 Bodo residents, whose lives were devastated by the 2008 spill. The case will come to trial in London, later in 2012.

We are all Senegalese

It is a good year to be Senegalese. Yesterday, Senegal beat Oman, 2-0, to qualify for the London Olympics football tournament. A proper celebration followed. They will be off to join Egypt, Gabon and Morocco in representing Africa at the tournament. This follows the country’s recent success in carrying a very-relatively peaceful elections and enshrining a new president, Macky Sall, at the end of March; while their neighbors have not wasted energy to bring coup d’etats back in fashion. At this rate, who knows what other goodies the Senegalese have in store for us? Is there anything that the Senegalese put their minds to that they cannot achieve? Is there? Well, there is that nagging issue of the “Talibés” on our streets.

Talibés are beggars boys, the vast majority under 12 years old and many as young as four, entrusted to spiritual care of religious Marabouts (teachers) by their families to learn the Koran and, apparently, the virtues of humility. Often in dirty and ripped clothes, barefoot and filthy, empty cans and plastic bowls in hand, these “boys” can be found in the streets, motor parks, squares, corners and dredges of Dakar at almost any hour of the day or night — begging, sometimes singing, for alms from passers-by to meet a daily quota exacted by their ‘marabouts’, or face beatings. Apart from these “home” beatings, many of the children are also exposed to diseases, injuries, physical, verbal and emotional abuse by “normal” members of society; and are victims of sexual and fetish ritualistic predators. Sadly, there are no official statistics on these abuses towards the children. Children’s rights groups estimate that there are between 8,000 and 10,000 of these beggar children in Dakar alone; and up to 100,000 across the country, with multitudes being trafficked from The Gambia, Mali, Guinea Bissau and Guinea to Senegal for forced begging by unscrupulous marabouts. Ergo, Senegal has become a transnational trafficking destination for beggar children.

This is not a new phenomenon and despite past “best” efforts of the Senegalese government and NGOs in the country, there is a real fear that the problem is actually growing rather than easing. In the past couple of years, the government of Senegal has notably defined forced begging as a worst form of child labor and criminalized forcing another into begging for economic gain but has yet to implement the beneficial legislation. In addition, some national and international NGOs have attempted to utilize soft policies, including feeding and temporary housing centers for talibés, which have inadvertently become incentives for some marabouts to move to the cities where the programs run, in order to fill the gap left by the government.

So here we find ourselves: The New Type of Senegalese that can do anything we desire. We do not need western saviors or crusaders to solve our problems. We preserved the constitution and drove out Wade & Wade with the power of our votes. We elected a new president that is proving early to not only talk but walk the talk. We brought a real daughter of the soil into the statehouse for the first time in history. We have stopped harboring murderous ex-dictators and have become a refuge for forcibly ousted democratically elected leaders. We are off to represent Africa in the Olympics, and will bring back the gold award, inshallah. Taking our children off the streets should prove to be no problem if we put our minds to it. The question is: Are we going to make ridding the streets of Senegal of this societal ill that is destroying our children, souls and future a national priority?

Parisian Africa: The artistic intersections of the Métropole

Guest Post by Lara N. Dotson-Renta

Paris has always been renowned for its culture and support of the arts. Yet, as France has grown into an ever more pluralistic society, the traditional image of what constitutes art in France must evolve as well. Younger generations of artists, many immigrants of African origin, are now reconfiguring the arts in France on their own terms. Their artistic production embodies experiences of travel and adaptation via the integration of the cultures and traditions of their respective countries of origins along with aesthetic and quotidian experiences that reflect daily life in France. Particularly in the realm of music and film, the blending of African tradition with French popular culture and youth genres has fostered a vibrant arts scene that, while initially seen as of/from the margins of both society and the arts scene, is actually renewing ‘mainstream’ culture in dramatic ways. You just have to scan the pop music featured in Hinda Talhaoui’s Paris is a Continent Series on AIAC. One proponent of this new artistic vision is Alain Kasanda (Apkass), a Franco-Congolese musician, spoken word artist, and founder of the O’rigines Foundation and the Ghett’Out Francophone Film Festival. I interviewed Alain at the Trinity College International Hip-Hop Festival held in Hartford, CT, in March earlier this year.

The interplay of jazz, drums, and hip-hop (or spoken word) all claim origins in Africa. What has the reception to such an artistic approach been in Congo as well as in France?

I would respond to that question by speaking of the way in which my music has evolved. I have listened to hip-hop since 1991, and I started to make hip-hop in 1997. I was born and raised in Kinshasa; I arrived in France when I was eleven years old. This is very important to my artistic trajectory. I discovered hip-hop upon arriving in France. In Congo, I would most often listen to what my parents listened to, frequently the Congolese rumba: Tabu Ley, OK Jazz, Franco, Zaiko… All of those groups fashioned my childhood and my imagination. Since we didn’t have television, I had little to no access to Western images. In any case, in Congo there were only two channels at the time: the state television of Congo and the national channel of Congo-Brazzaville. We were less subject to the barrage of Western images than we are now, with hundreds of satellite channels available in the Congo. Between the state channels, the private channels, and international stations, it’s an onslaught of information and imagery that descends upon the Congolese population.

It was after my arrival in France that I discovered hip-hop. As an adolescent, I started to make my own music and the groups that most influenced me were typically French rap crews, such as les Sages Poètes de la Rue and Démocrates D. At that time, French hip-hop was barely discernible from American hip-hop, in that it was about blending jazz influences with a break beat. It’s along those lines that I joined the movement. At the beginning, my writing output was a reproduction of what I was hearing. As I grew up and matured, I became interested in black African poetry; I discovered David Diop. My approach towards writing evolved from there. Little by little, I liberated myself from the obligation of rhyming, in order to instead explore meaning through prose, to be freer in my writing and to try to capture depth rather than simply form.

My approach towards music has followed a similar path, shaped by encounters. I discovered an artist whose musical approach greatly influenced me: Gil Scott-Heron. His first album, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, is voice-percussion. It shocked me to listen to it… That manner of embarking upon music, as a vessel of many influences, truly touched me. When I started to create my own album, I started spending time with musicians, some of whom I shared a stage with, a number of whom were from Mali.

I did a lot of things in Paris, like putting on film showings and writing workshops. One time, following a workshop, I shared a stage with two kora players. They were Malian. It was as if lightning struck. We simply did a spoken word hour; I recited my texts a cappella and they accompanied me on the kora. I told myself how magnificent this was, that this must be integrated into the album. So it’s through maturing, the things I was able to discover through literature and a sort of researched music, as well as human encounters such as that with the Malian musicians that I began to incorporate everything into my music. I also made a place for things that pleased me, such as 1970’s soul, jazz, but also African music — the n’goni, the kora, the calabasse, and the congas, which I particularly love.

But as to why I chose to include all of those instruments in my first album? To begin with, because it’s beautiful. It’s not fair to say that because it’s African it will be put in, but rather because it’s magnificent, that it brings true musical color. It equally has to do with re-engaging with the cultural patrimony of one’s place of origin, where I come from. I identify in equal measure to Congo or Mali as I do with any African country. I have a pan-Africanist vision of things. I don’t simply look at what happens in Congo, but I also see what can inspire me from what happens next door. The kora isn’t really an instrument of Central Africa, but rather of West Africa. It’s the same with the n’goni. I integrated them into my music. You can see a little of the path that led me to exit the canon of French hip-hop in order to transform, adapt, and integrate it to my personality and my vision of music, which has also evolved over time:

Hip-hop is well-established in France, since the days of artists like MC Solaar and Assassin, among others. In your opinion, how has the landscape of hip-hop changed in France as well as in Africa in recent decades?

I can only speak to my own experience and the way in which I have integrated that history and how it has evolved within me. I began listening to hip-hop in 1991, and the groups that were popular at that moment such as NTM, MC Solaar, IAM… Being eleven or twelve years old at the time, I absorbed from these groups a kind of integrity at the level of research, a form of social and political consciousness that is less pronounced than in what is produced today. They were nevertheless ‘mainstream,’ the only groups that were truly visible. At the time, the Internet didn’t exist and it was much more difficult to reach the wider public. The groups that persisted did so through traditional means: record labels, radio, television, singles, albums… They had a very directed production scheme, very different from what happens today. That has its good and its bad.

In any case, I find that the advantage of that time is a very marked social and political awareness. You can find it again today, as there are always artists that are politically and socially engaged, but I have more a sensation that trends towards an impoverishment of musical research in French rap today. There is an impulse to want to exit one’s social class rather than a desire to transform the discourse on class in French society. That’s a bit of what I decry: that behind a discourse, one that could actually be a dialogue on social vindication, one finds instead the aspiration to emerge from one’s own social condition rather than to put into question the established order. The artists remain in the order of describing the quotidian. They never go very far in real criticism of the system in which we live, the hypocrisy of racism “à la française,” and the model of integration in which you see grave fissures, notably in the realm of political discourse. This is what disappoints me somewhat with regards to what is happening today.

And also, there is the base and there is the form! A musical form that speaks to me, nevertheless. When you listen to IAM, when you listen to certain groups of the time — even MC Solaar — you are in fact listening to Bob James, you’re listening to James Brown. That kind of education interests me as well. I came to soul through friends who initiated me, certainly, but also because in buying a record, in buying Main Ingredient by Pete Rock & CL Smooth, I recognized that they were sampling Curtis Mansfield, or someone else. Little by little, you open your ear to other music. Once you arrive there, and once you start to want to make music yourself, you know then where to trace back the source from soul. It’s in that sense that, even at the level of musical research, I recognize myself far less in what is made today, in the sense that there is no longer that recognition of melody by the sample, for example. You find expanders, sounds that are a bit monotone and binary, and much poorer. I feel that there has been an impoverishment of sound, because the artists drift more towards electro than toward a sound that is more warm and organic, as in the beginning of the 1990’s.

Really, I’m a bit more ‘old school.’ I stayed in that time. Even in American rap, which has evolved quite a lot as well. I’m talking about the Chronic and all of that, and I prefer even so what was made in 1995, like Group Home, Gang Starr… That’s what I like to listen to. For me, the date limit on American rap, the moment when I felt a sort of turn, was the middle of the 2000’s. Or even farther. There was Black Star, Mos Def, there was Mos Def’s solo, and after that the Soulquarians where the decline began, where things were not being made in collaboration anymore. At the beginning of the 2000’s, there was yet a hope for a renewal in hip-hop. You came back to the source of the 1970’s with the Soulquarians, Like Water for Chocolate, Erykah Badu, The Roots… There was truly a will and a desire, even in the clothing look, to come back to an era — the 70’s — and a looking back to the sounds that they clearly invoked. After, we came back to things that were more ‘dead,’ less warm, less organic in sound. It’s a bit of what I deplore.

In the next album that I am in the middle of creating, that I set in that time in Paris, I search for the inverse. We started from sampling in order to reinterpret everything for musicians, and so that there would be that evolution of music, not just something that falls on four measures, or two measures on loop for four minutes. And so you see the evolution that I see in French rap.

You’ve established film festivals such as Ghett’Out in the United States, which offers an innovative view on the Francophone world. I would like to know more about your organization “O’rigines”.

I started the O’rigins Association in 2003. At the time, I was studying studying cultural communication, so I decided to start this association to organize seminars in various places. I started in a Senegalese bar in Paris in le Marais, le Djoko, organizing monthly screenings of documentaries, the “Cultural rendez-vous of Djoko.” We would screen a film followed by a debate with an author who presented his book, addressing the same topic as the film. The intention was to link the film to the literary world. It could be poetry, essays… many things. We did that for some six months, under rather difficult conditions. We’d play the VHS through a video projector! Gradually, we gathered more resources, and I moved to larger rooms. In 2006 I went into a partnership with a movie theatre in Saint-Michel. We could start showing short films in 35mm print, in real film. These were the “Tell me a short” evenings to link poetry and short films. The common point between the two is that they are short forms, they must tell things on very few pages, in a very short time. Each evening had a theme. I screened four films a night. Each short film was preceded by the recitation of a poem that addressed the same topic as the film, but without talking about the film itself. After making a selection of films, I called slammers from Paris, mostly friends. They watched the films and let them be inspired to write a poem. On those evenings, there would then be the reading of the poem and screening of the film, after which the director joined the poet to discuss among themselves and with the public. The goal of the association was to try and create social ties through art, and specifically through film.

This year I organized for the first time the Ghett’Out Film Festival. It’s a pun — “leaving the ghettos” — but also a nod to a song by Gil Scott-Heron, “Get Out of the Ghetto Blues” off the ‘Free Will’ album. The idea is straight-forward: to show independent French films, made by filmmakers working at the margin of the French system of production and distribution. Basically, these are people who have interesting discourses and a styles, but not necessarily the means of production and distribution needed to reach the public they should reach. Let me give an example. French filmmaker Sylvain Georges. He made a beautiful film, Qu’ils reposent en révolte (May They Rest in Revolt). From 2007 to 2010, he followed migrants, mostly Afghans and Eritreans, who try to reach England from Calais. Here’s a fragment:

He has followed several people in an equal relationship between filmmaker and subject. He didn’t just arrive on the scene as a cameraman. He has mostly ‘constructed’ political figures. There is no compassionate report, where they’ll say “those poor migrants …”. We see men and women with a history, products of political situations, who leave a country because of war, or because the social and economic conditions are not good. When they arrive in France, the only answer they’re given is one of repression, the populist and safety talk of Sarkozy… This is a film with a strong social and political vision, but also a film that remains poetic. He films them in the environment they find themselves in: among twigs, trees, the sea, birds. There is also no voice-off. There are only these situations, which the filmmaker shows one after the other. The viewer himself is brought to think and understand the distress the people are forced to live with, and how they survive.

The essence of the festival was to present these kinds of movies, both feature films and short films. Soufiane Adel’s short films for example. He made a fictionalized trilogy about his family. He tells a story, introspectively, but through fiction. All characters in his films are family members: his father, his mother, his sisters. They all tell stories. Kamel s’est suicidé six fois, son père est mort tells the story of an old man who dies in palliative care, late at night, and how his grandchildren improvise a Muslim funeral rite. They begin to pray in the room. His son arrives too late; his father is already dead. That is all the film tells, with very few words. It lasts nine minutes. It’s beautiful.

So it’s about bringing these films, which don’t get the public in France they deserve, to an audience of film buffs and students in the United States. Since programming a film doesn’t necessarily guarantee an audience to come watch it, the idea was to also organize on the sides of the festival itself. There have been meetings at universities, with filmmakers and students and teachers interested in the topics covered in the films. The meetings focused mainly on two issues. The first question is: what does it mean to be an independent filmmaker today? In terms of financial constraint, but also in terms of intellectual freedom. In other words, what is the price of freedom? And also what does freedom mean? The second question is: why choose to be a filmmaker, why choose to explore those themes? It was about creating a framework in which the filmmakers could express themselves around those issues, far removed from French cinema. I also wanted to establish a link with the tradition of the American counter-culture, which I’m not all too familiar with, but one of its filmmakers had a big influence on me…

This is also somehow my undertaking, because when I look at French cinema, when I watch French television, in no way do I recognize the society I see in the subways or on the street. Blacks, Arabs, Chinese, the other, all are discarded; on TV and film, France is portrayed as very white and very bourgeois. This issue of representation is crucial, because it comes with a language of alienation. Representation is really important and this is what the festival films show: France as I see it. Where one sees all the social parts, which are generally sidelined in France’s image but also often attacked in the political discourse: the working classes, the immigrants … And who are mostly objects rather than subjects in the public space. They only become subjects in front of the camera of people from their midst. Thus we get to see their history from a different angle and with much more empathy. Without forgetting the form, the poetry, which is also important. It’s not about having a revengeful discourse that dismisses beauty. It’s about the search for beauty while addressing issues that are never addressed. That was the aim of the festival, which is in line with my musical interest: how to express hard things, but through beauty and form. In hip hop and in the cinema, that is what interests me.

* Lara N. Dotson-Renta, PhD, teaches at the College of Arts & Sciences, Quinnipiac University. The interview was transcribed by Pénélope Cormier and translated from the original French by Lara and Tom.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers