Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 539

April 30, 2012

Mali–don’t talk about somebody’s mama

Monday evening, and it’s hard to tell who’s shooting up Bamako, or why. But someone cracks on Twitter “béé b’i ba bolo.” It’s one thing to stage a counter-coup or settle a score (if that’s what’s going on), it’s another thing to talk about somebody’s mama.

“Béé b’i ba bolo” was one of the great foot-in-mouth moments for ATT, Mali’s former president, deposed in a coup on 22 March. “Everyone is in the hands of their mother” sounds like a sweet sentiment to express on International Women’s Day, when ATT let this particular bomb drop at the Muso Kunda (the Women’s Museum) a couple of years ago. But the other meaning of the phrase—the one ATT did not intend—is basically “save yourselves!” or “every(wo)man for him/herself!” At the time, ATT’s opponents got their jaws around this one and wouldn’t let it go. A president of the republic who is not ashamed to tell his people or his soldiers to “save themselves!” What a humiliation for Mali, they said. ATT called on the griots, people whose eloquence exceeds his own (Bambara is not ATT’s first language, and a lot of people say his use of it is more functional than profound). They took to television and the radio to explain that what the president meant to say was, well, what it sounds like in a direct translation: everyone has a great debt to her mother. Too late. The damage was done. People started to say that ATT, the ex-soldier, was abandoning his troops in the North and letting the situation in the rest of the country rot. They said he cared more about watching soccer, drinking tea, and chasing women then he did about running the country.

That never seemed fair, but that little dust-up now seems quaint. I hear there’s a reddish fog hovering over Bamako the last day or two. Yesterday, flights were cancelled because of it. Tonight, reports have it, there’s fighting for the airport, the TV station, and around the garrison at Kati. Tomorrow?

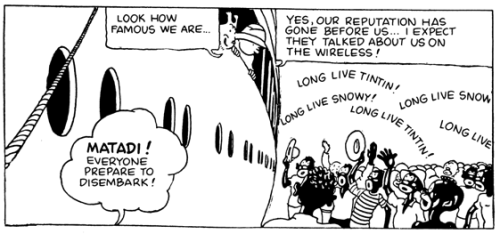

The adventures of Tintin in the Land of the Law

In Belgium, a Congolese student and a minority organisation sought to obtain a ban on the comic book ‘Tintin in the Congo’. A Brussels court rejected their claims. Despite this outcome, the reasoning of the court jeopardises free speech. As regards the applicants: ‘offensive as the comic may be, their recourse to the law is both misdirected and counterproductive,’ Jogchum Vrielink argues in this guest post.*

Tintin, the brainchild of Hergé († 1983), is experiencing new and exciting adventures these days. Not just in the cinema, but in Belgian courts as well.

Bienvenu Mbuto Mondondo, a Congolese national studying in Brussels, filed suit to obtain an injunction against the continued publication, distribution and sale of the comic book Tintin in the Congo (Tintin au Congo), as well as seeking to have the book withdrawn from bookshops and libraries in Belgium. Mondondo did so on the basis of alleged violations of the Belgian anti-racism legislation. In subsidiary order he demanded that a disclaimer be printed on the comic’s cover, warning of its offensive nature, along with the inclusion of an introduction of a similar nature. Mondondo was supported in his claims by the minority organisation Conseil représentatif des associations noires (Cran).

On 10 February 2012, the Brussels Court of First Instance rejected all the applicants’ claims. The Court also rejected the counterclaims by Casterman, the series’ publisher, and Moulinsart, the company which was set up to protect and promote the work of Hergé. Both had asked for 15,000 euro as compensation for ‘vexatious proceedings’.

Tintin in the Congo

The comic Tintin in the Congo was first published between 1930 and 1931, a time when Congo was suffering under Belgian colonial rule. The album graphically depicts the Congolese as monkey-like, and portrays them as stupid, childish, and lazy. In later years, when a colour version of the album was published, Hergé made several changes to it, partly because he acknowledged that the work was overly influenced by the colonial ideas of its time. In the new version the stereotypical caricatures of the Congolese were rendered somewhat less extreme, for instance. Several textual changes were made as well, and most references to Congo being a Belgian colony were removed.(1)

The album has regularly been a cause for debate, particularly in the Anglophone world. Due to on-going controversies it was not published in English until 1991. The colour edition did not even appear until 2005. When finally it was published (by Egmont Publishing), it included a cautionary wrapper indicating that it contained “bourgeois, paternalistic stereotypes of the period” that may be offensive to contemporary readers. The edition also encompassed an introduction providing additional historical contextualisation. Nevertheless, in 2007 the (former) Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) asked the bookstores Borders and Waterstones to stop selling the book, in response to a complaint it had received. The CRE stated that the album contained “imagery and words of hideous racial prejudice, where the ‘savage natives’ look like monkeys and talk like imbeciles”:

Whichever way you look at it, the content of this book is blatantly racist. High street shops, and indeed any shops, ought to think very carefully about whether they ought to be selling and displaying it. Yes, it was written a long time ago, but this certainly does not make it acceptable. It beggars belief that in this day and age (…) any shop would think it acceptable to sell and display ‘Tintin In The Congo’. The only place that it might be acceptable for this to be displayed would be in a museum, with a big sign saying ‘old fashioned, racist claptrap’. (“CRE Statement on the children’s book ‘Tintin in the Congo’”, Press release, 12 July 2007)

The bookstores refused to remove the comic from their shelves entirely, but they did move it from the children’s section to the adult section of graphic novels. Other British retailers sell Tintin in the Congo along with a label that it is unsuitable for readers under the age of 16.

In the US, plans by Little, Brown & Company to publish the colour version were abandoned altogether in 2007, seemingly on account of the controversies in Britain and Belgium. To this day Tintin in the Congo remains the only album in the Tintin-series never to have been published in the US. Furthermore, some libraries have restricted public access to the album. Brooklyn public library, for instance, has kept the comic under lock and key since 2007, due to a request by patrons and library employees, rendering it available only upon request and appointment. Other controversial works, including Hitler’s Mein Kampf, are readily available in the library’s open shelves.

Colonial representation and contemporary harassment

Judged by contemporary standards, Tintin in the Congo is blatantly colonial, highly paternalistic, and offensively stereotypical, to say the least. The question, however, that the Brussels Court had to answer was whether its present-day publication and distribution could be legally prohibited under the anti-racism legislation. The Court rightly rejects this possibility.

The Court first rejects the claim that publishing and distributing the comic amounts to ‘harassment’. Harassment is legally defined as “unwanted conduct connected to a person’s race or ethnic origin with the purpose or effect of violating the dignity of a person, and of creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment”. According to the applicants this definition was satisfied by the publication and sale of a comic book containing ideas and illustrations that are offensive, degrading, and insulting to people on the basis of their origin or skin-colour.

In response, the Court states that neither the album itself nor its dissemination and sale have the purpose of violating anyone’s dignity or to create a humiliating or offensive environment. In light of the legal definition of harassment, the question that remained to be answered – according to the Court – was whether it did not have this effect either. The Court again answered this in the negative, judging that “the continued sale, in our era, of a comic book created in colonial times, suffused with the ideas and attitudes of its time of creation, cannot be regarded as violating the dignity of a person, or group of persons, protected by the Anti-racism Act”. Especially, the Court continues, since the commercialisation of the album is an integral part of the sale of the complete works of Hergé, “without there being placed any special value on the comic book in dispute”.

Although the outcome ultimately is that the sale and distribution of Tintin in the Congo cannot be prohibited, the Court is nonetheless insufficiently critical of the premise of the applicants’ arguments, which are simply based on a mistaken idea of what (legally) constitutes harassment. The applicants believe the prohibition of harassment to entail a general ban on all speech or illustrations that are humiliating or offending to people on the basis of their protected characteristics (in this case their skin-colour or ethnic origin). This broad interpretation disregards both the language and the spirit of the harassment provision.

The prohibition of harassment, derived from (and imposed by) European discrimination law (which was inspired, in turn, by the North American experience), was designed to counter forms of person-oriented harassing, pestering and stalking behaviour in the workplace and other societal contexts, such as the provision of goods and services. The prohibition’s aim is to remove immediate barriers and obstacles to societal participation for individuals belonging to protected groups. In Belgium, the prohibition of harassment has been extended to cover the entire scope of the anti-racism legislation. However, and this is essential, it still requires the violation of the dignity of one or more concrete persons, and not of an abstract group such as ‘the Congolese’ or black people in general. The legal text explicitly refers to ‘a person’: clearly, this language was not intended to cover mediated and impersonal types of ‘group defamation’ by means of the mass-media or comic books. It is limited to (anti-)social situations in which someone is the direct and personal object of unwanted conduct with the ‘purpose or effect’ of affecting one’s dignity. In no way was this the case here.

Even if one adheres to this strict, person-oriented interpretation of discriminatory harassment, the concept already yields significant tensions with free speech principles. However, if one accepts the ‘impersonality’-premise of the applicants – as the Court does – the anti-harassment provision is rendered virtually limitless, amounting to an open-ended prohibition, targeting any and all speech that somehow ‘violates the dignity of a group’. Needless to say, this would result in unprecedented, and patently unconstitutional, restrictions on the freedom of expression.

Tintin and hate speech

Another set of the applicants’ claims was based on the hate speech provisions contained in the Anti-racism Act. This concerns firstly the prohibition of ‘incitement to discrimination, hatred or violence on the basis of colour and ethnic origin’ and secondly the ban on the ‘dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred’. Both provisions are derived from the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD).

However, their seemingly broad drafting notwithstanding, these provisions are interpreted very restrictively by the Belgian Constitutional Court. Regarding ‘incitement’ the Constitutional Court requires active instigation of third parties to undertake certain actions. Apparently finding the term ‘hatred’ too vague and subjective in its generic meaning, it even specified that only incitement to hateful acts can be considered unlawful; thereby excluding incitement to merely negative attitudes or feelings from the realm of the provision. Finally, the Constitutional Court requires the presence of malicious intent for the incitement clause to be applied. In other words, aside from the requirement that, given the content and the context of the words used, the impugned expressions must incite and provoke violence or discrimination, it must also be demonstrated that the latter was the defendant’s conscious and malevolent intention.(2)

Similarly, the prohibition of ‘disseminating racist ideas’ has been construed narrowly by the Constitutional Court. Here too the Court requires special intent. More specifically the dissemination should have as its demonstrable aim to ‘incite to hatred and to advocate and justify discrimination and segregation’ of the targeted group. Regarding content, the speech – in order to be prohibited – must be ‘contemptuous, hateful and malicious’; specifying that it particularly targets expressions of ‘classical’ biological racism.

In the light of this, it was unsurprising that the Brussels Court came to the conclusion that (the publication and dissemination of) Tintin in the Congo did not meet the standards of the hate speech provisions, and that an injunction could therefore not be justified on that basis. The Court concluded that the claims failed due to the ‘evident absence of the required malicious intent’, both on the part of Hergé, and on the part of Casterman and Moulinsart. Having established this, the Court deemed it redundant even to investigate the additional arguments brought forward by the claimants.

This approach is somewhat regrettable. At least, it would have been (even) more convincing – as well as more logical, legally speaking – if the court had first assessed whether the contents of the comic were sufficient to meet the threshold-level required for the offenses, instead of looking exclusively at the required intent. The former is also clearly not the case if one applies the rather strict requirements adopted by the Constitutional Court. Taking this approach would have served to clearly demarcate the space available for free speech, something which the sole reliance on the – inherently subjective – element of intent fails to do.(3) This is all the more important since the fundamental problem with the claims is that they would simply open the floodgates for innumerable additional prohibitions, if they were to be allowed. Tintin in the Congo is undoubtedly offensive to many people, but if its contents are brought under the prohibitions of the Anti-racism Act, then an endless list of other works would also wind up in the crosshairs. This is true for most religious books, as well as many of the great literary works, and the writings of virtually all great thinkers of early modernity. Allowing a legal ban on such speech therefore implies the abolition of freedom of expression itself.

Counterproductive

All things considered, it is puzzling that the applicants opted to pursue a judicial solution in this case. In doing so, they could only lose. It was clear, from the start, that the comic’s contents – albeit offensive – did not amount to a violation of the anti-racism legislation; let alone that this would be the case for publishing and distributing it.

Mondondo indicated that now at least Tintin in the Congo is the object of debate and discussion, and that he would persevere due to that ‘success’; even claiming a readiness to go to the European Court of Human Rights. Mondondo not only appealed the civil ruling by the Brussels court, but also initiated criminal proceedings against Moulinsart en Casterman. Moreover, in 2009, he extended his case to France as well.

Mondondo’s view however ignores the counterproductive effects that the legal approach has for his cause. Admittedly, the complaint as well as the ruling have received significant media attention. However, the content of the coverage was predominantly of a negative, or even mocking, character. Precisely because Mondondo and the Cran opted for a legal solution, the applicants were routinely portrayed as overly sensitive, ‘politically correct’, and bent on censorship. Even the Centre for Equal Opportunities – the Belgian agency responsible for enforcing the federal discrimination legislation – warned against “over-reaction and hyper political correctness”. In other words, the legal approach has not given rise to the desired critical discussion about the comic itself.

In fact, quite the opposite is the case. Firstly, there have been unintended commercial effects, to say the least. Sales of the album rocketed, following the British discussion about a ban, by as much as 3,800 per cent. The comic temporarily even jumped to the 5th place in the Amazon bestseller list, coming from the 4.343rd place, 4 days earlier. The lawsuit(s) in Belgium had similar effects, causing the French version of the album to temporarily go out of stock. Secondly, and more fundamentally, the lawsuits shut down discussion rather than promoting it, by the aura of legitimacy that the inevitable rejection of the claims and the equally inevitable future acquittal yield. These outcomes wrongly suggest, to the general public, that there is nothing wrong with the ideas on which the work is based, while in fact these do require critical debate and analysis. However, instrumentalising the law and the court system for the purposes of this debate seems both misdirected and counterproductive.

* Jogchum Vrielink is a Postdoctoral researcher and Research Coordinator Discrimination Law (Research Centre on Equality Policies, University of Leuven).

Endnotes

The geo-branding war

Geo-branding is a serious thing. It is particularly serious when people from other geographic areas decide to brand your geographical area and the people in it, the way they see fit and the way that fits their purposes. No other country, region or continent, I’d argue, suffers from other peoples’ nonsense as much as the continent of Africa. Actually, the reason why people generally and casually talk about Africa as one place is because of what Nigerian-American author C. P. Eze refers to as “their geo-branding war”.

Warfare indeed. Eze of course is concerned with business. He argues that the image issues instigated by outsiders – oftentimes the representatives of the aid industry – hurt the business sector as the whole continent is seen as unworthy of investment. Very importantly, according to Eze, an increase of just 1% of Africa’s share of global trade would bring in US$70 billion annually; more than all aid and debt relief combined. Yet the trade with African countries is not encouraged much in the West. I have made mention of Eze’s book before, and I, as much as many others here, have written about the role the NGO sector plays in news gathering from the African continent – in short a very central one. There is no shortage of these pseudo-selfless, supposedly well meaning case studies around so lets have a look at a current one.

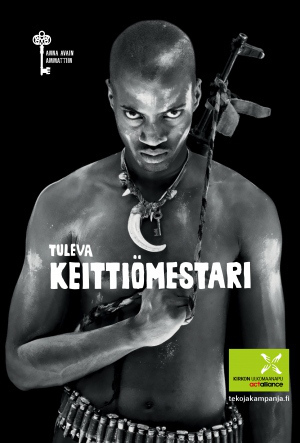

At the moment I am based in Helsinki, Finland, and currently all over town we are bombarded with images of a new advertising campaign.

Seemingly endless amounts of paid posters with a model depicting a generic shirtless African rebel soldier with baby-oiled-slash-sweaty body and an intense look, carrying a rifle on his back, squeezing the strap in his fist and wearing some kind of necklace, which may or may not be intended to appear witchcrafty, and a belt full of ammunition. All this makes him look like some kind of Nollywood version of Rambo against a dramatic black background. The text in the advert says “future chef” and the key that is dangling from the aforementioned necklace suggests that he needs to be given a key to a better job opportunity. That metaphoric key in real term means our financial donation and perhaps a signature in a petition which, the campaign promises, can change the destiny of this poor soul.

There are other images too; some of them featuring other models, some with the same male model, now smiling with a little less witchcrafty necklace and his upper body no longer bare, but covered with a worn-out t-shirt advertising the first US Iraq war effort from the early nineties. I am scared to even attempt to attach meaning to it. According to the photographer Antti Viitala these photos were taken in Cape Town, South Africa and the campaign was designed by Helsinki based advertising agency Dynamo. Viitala says that the models used had been spotted on the streets of Cape Town.

So they are just that; models who broadly appear to fit the purposes of the campaign. For the gentleman in the leading image that means that basically he’s black. That is enough.

The campaign is run by Finn Church Aid, a missionary and aid wing of the Finnish Lutheran Church – the state church – which especially in recent years has struggled with negative stereotypes of their own in the form of homophobia that undeniable exists within their ranks. They don’t like to be represented in a simplified manner themselves, but when it comes to others, this moral consideration is less central. The campaign is a high profile one. Its patron is Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former President of Finland Martti Ahtisaari (1994-2000) and the purpose is to both influence politicians and to raise funds. Of course it has to be said here that this problem at hand is bigger than this campaign. It’s a global issue, mainly instigated by the civil sectors, some media and a traditionally inaccurate and one-sided history of colonialism that is still being read and told in the countries of the global north. True, the Finnish church is follower rather than a leader in this, but I am curious to know a bit more about what goes on when an idea like this is born. After asking from the photographer – who was helpful but who also wasn’t sure what my point was; and I felt that that in itself was noteworthy – I emailed the public relations and communications officer Veera Hämäläinen, who is part of the team behind this campaign to hear her version of the story.

The first thing I realised from our correspondence is that Hämäläinen and I really see this whole phenomenon differently. She insists that the campaign is a positive one. She mainly feels that way because the text in the middle of the poster suggests that this shirtless rebel soldier is a future chef. So this is a positive transformation and the video version of the advert and further reading material on the campaign’s website explains this to her satisfaction.

Here’s that video:

Hämäläinen also believes that Finns are clever enough people to understand the simplification. I, as a human being, but one that could also be described as a Finn, would strongly disagree.

I watched the ad online, but haven’t seen it on TV yet – even though in our household the TV is on quite a bit (maybe our family doesn’t watch channels where church would advertise on). What I have seen, however, are tons and tons of these posters. I couldn’t imagine that under any circumstances would I have read the additional information online if I didn’t decided to write about this. I think it’s ambitious to think that people would take anything other from this campaign than, yeah, that’s Africa alright; always in trouble and always needing help–our help–nothing new. I wish this wasn’t the case but I have lived this life and heard people speak, even many very clever ones, so I am not just trying to be negative about it. I am trying to be realistic: these images have just been used as they were considered as the most effective ones regardless of their nature. Also, and I really don’t even wish to take this opportunity to be too sarcastic about it, but questioning its sources hasn’t traditionally been the church’s, or its followers’, strong point.

So I’d argue that what we are really left with is the poster and for the most part its photograph. There are a lot of these images everywhere – there hasn’t been this kind of ‘military presence’ on the streets of Helsinki since the 1940’s – but now this what appears to be a two-dimensional cloned nondescript African rebel army stares at me from my neighborhood bus stop, all the way to the office, to town and pretty much anywhere else I might want to go. From a distance, in a hurry or uninterested, one is not able to read the text – or just care to read it – and the imaging is building on our collective prejudices, our already existing ideas of Africa. I am not talking about any silly magic bullet theory here, but this is part of the same narrative that has been explained to us in media, school books and also very importantly in these aid campaigns. It’s not a question of this, or any other country’s collective cleverness, because this doesn’t break a pattern. It continues it like there simply was nothing wrong with it and based on my correspondence with campaign people I am getting a distinct sense that they don’t have any issues around this representation.

It’s quite curious how it is possible to see one thing differently. Hämäläinen explains that this campaign is unlike the ones before it: “We have chosen a different angle,” she says, “not always using images of starving children, but for a change strong young people from developing countries, who are able to be in charge of their future as long as they are given the right tools.”

So that’s what this is about: breaking the pattern. I admit this guy is no child – even though they may have been generous with the baby oil – but I just can’t see how this is a complete departure from the traditional style of imaging aid campaigns. It still communicates three very traditional ideas: 1) Africa, 2) problem and 3) ’our help needed’. I am wondering how this impacts the many people from around Africa who live and work in Finland? Is there no chance that the negative attitudes towards immigrants are strengthened if the native people conclude that we have basically done a massive favour to each and every one of them? I ask my South African wife and she’s not impressed, but of course the point here must be that one doesn’t have to be from Africa to see and condemn the problems of these image politics. Too many people are still thinking that if it’s not directly about you, then why complain. But that’s nonsense. We are all people here.

Then Hämäläinen surprises me by mentioning that this is not just about Africa though. Youth unemployment is a global issue. Of course she’s right. She continues to say that for this campaign however the developing world is the target. So not Africa as such but, (even) more broadly, the developing countries in general and this single image has been selected to communicate that. If you carefully read the website you’ll find mention of specific countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Honduras, although by now I think it is evident that my focus is less on what the project is about and more how they choose to communicate it. I think it would also be misleading to suggest that the small print and the big print are as effective. I’d venture a guess that not many of the ones seeing the poster will read all of the material available.

How about the trade aspect? I am wondering what this kind of campaigns that very much support our existing negative ideas of Africa – again, very generally – do in a long run to the trade? The attitudes of the business sector? Does it matter? “Trade aspect is important,” she admits, “it’s important for it to grow. In this campaign we have wanted to highlight one angle and describe the magnitude of the problem at hand – 80 million unemployed youth and most of them in the developing world – and something must be done on the grassroots level although of course, politicians could also use their own forums to make difference.”

Fair play, except essentially that is to say politely that as important as trade may be, it’s got nothing to do with us.

I am not suggesting that any overtly positive spin should necessarily be applied – just information that is more accurate, balanced and with a bit more context. Are we Europeans (North Americans, Australians, etc) so jaded that we need to be hit on the head with the worst of problems before we will react? I am asking genuinely since I don’t have an answer to this question. I have been thinking about the ethics of development aid work a lot and I think it’s still something where a lot of dialogue needs to be had.

Neither am I suggesting that these campaigns never have any positive results, but I have seen this sector enough to say that they advertise to both justify and secure their own existence and function. I know that these organisations often have glass ceilings for the staff members from the southern partner countries and I think that the aid industrial complex is altogether… well, a complex matter, but is there a realistic way for it to be something other than patronising and enforce the pre-existing ideas of geographical – and I can’t leave it unsaid, ethnic – hierarchies that are around, no matter how much you or I may wish they were not?

My understanding of this whole situation could be summarised by my five year old son’s current key phrase. “This is unfair.” I would like to think that this is more inconsiderate than evil, but we are playing with images of real people, and therefore their lives here. People are not some kind of mascots you can freely use in any way you wish for fundraising purposes in order to be able to hire yourself to help them. One problem doesn’t mandate you to create another problem. At the very latest, now is the time to discard ‘good intentions’ as sufficient justification to absolutely any shock tactics or otherwise. The Finnish church and their ilk won’t do it, but as people, surely we need to start questioning the dominant practices of aid advertising. It would still be better late than never.

April 29, 2012

Sunday Bonus Music Break

Since Friday’s Special was reserved to Sierra Leone — and for archival purposes — here’s your Sunday Bonus. First up, above, from the same label that brought us Baloji, Konono N°1 and Staff Benda Billili comes a new recording by Jagwa Music: ‘Live in the Streets of Dar’ (es Salaam, Tanzania).

‘Night in Tunisia’, the opening track from Hugh Masekela’s 1974 LP ‘I am not Afraid’:

Fatoumata Diawara’s ‘Kèlè’:

Remember DJ Cleo’s FaceBook? This is the Twitter version….

Alabama Shakes played ‘Be Mine’ live on Jools Holland:

From that same show: The Chieftains with Carolina Chocolate Drops.

Fuse ODG’s ‘Azonto’ gets a make-over:

YaoBobby’s deceptively naïve ‘Mémoire d’un continent’:

Blood Orange’s Champagne Coast went viral this week. We can see why:

The Very Best return after a long silence with ‘Yoshua Alikuti’:

And an interesting music video filming singer Jimetta Rosa at her actual job:

David Cameron’s Libya Doctrine

The British media has, in the last few weeks, been working through allegations that the nation’s secret services helped Gaddafi’s spies track down Libyan dissidents. On 21 April the Mail on Sunday published documents discovered in Libyan archives and detailing the hunt. First, it is alleged that MI5 were involved in the kidnapping of two dissidents who were abducted with their families in 2004 and taken to Libyan prisons. Secondly, in 2006 Libyan spies were allegedly welcomed by MI5 and treated to the luxuries of secure mobile phones and a safe house in Knightsbridge, a grotesque contrast with the conditions of asylum seekers in this country.

MI5 apparently passed on sensitive information to their Libyan colleagues to support the torture of dissidents:

One Libyan dissident, an accountant living in London, told the Mail he was shocked to discover that a photograph he had had taken when applying for a British passport in 2002 had been passed to the EOS and was among the recovered documents. He says he suspects that a telephone was being monitored, with the result that an associate in Libya was detained, tortured and then held for five years in one of Gaddafi’s jails. (Guardian)

This cooperation was part of the New Labour’s detente with Gaddafi, exchanging favors for oil and Gaddafi’s promise that he would get rid of his “weapons of mass destruction”. That government had been voted out by the 2011 intervention in Libya, which was supported by the new Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. If this easy ambivalence about globalisation has become Professor Blair’s legacy, it is one continued by his elected successor, David Cameron, who attempted to distinguish himself from his predecessor’s collaborations with Gaddafi by spending more money in the intervention than any other foreign state (Guardian).

Last year, Hugh Roberts’s article in the LRB gave little credence to the idea that military intervention was the only option. The article, Who said Gaddafi had to go?, provided an African context to the conflict which exposes the consensus claimed by the allied European governments as pure self-interest:

The claim that the ‘international community’ had no choice but to intervene militarily and that the alternative was to do nothing is false. An active, practical, non-violent alternative was proposed, and deliberately rejected. […] The International Crisis Group, for instance, where I worked at the time, published a statement on 10 March arguing for a two-point initiative: (i) the formation of a contact group or committee drawn from Libya’s North African neighbours and other African states with a mandate to broker an immediate ceasefire; (ii) negotiations between the protagonists to be initiated by the contact group and aimed at replacing the current regime with a more accountable, representative and law-abiding government. This proposal was echoed by the African Union and was consistent with the views of many major non-African states – Russia, China, Brazil and India, not to mention Germany and Turkey. It was restated by the ICG in more detail (adding provision for the deployment under a UN mandate of an international peacekeeping force to secure the ceasefire) in an open letter to the UN Security Council on 16 March, the eve of the debate which concluded with the adoption of UNSC Resolution 1973. […] In authorising this and ‘all necessary measures’, the Security Council was choosing war when no other policy had even been tried.

As so often, the ‘international community’ invoked in questions of moral difficulty (always, somehow, alluding to Britain’s greatest Brit) deliberately ignores the non-violent stance of those — the African Union and so many others — suspicious of the North Atlantic states’ oscillating appeasement and military conflict with dictatorships. The history of recent British relations with Libya serves as an example of how these governments continue to collapse self-interested policies with the moral conscience of “the world”.

Peter Goldsmith, New Labour’s embattled attorney general (who has turned from public life to more lucrative pursuits), commented on the most recent allegations:

We thought, I think the world thought, he had turned for the good, and he hadn’t. That was as it turned out to be a wrong judgment. Whether it was the wrong thing to do at the time, that’s another issue …

This moral equivalence, a repulsive blend of apology and self-justification, is typical of that government. This formulation — “We thought, I think the world thought” — equates regional commercial interests (we, the UK) with universal moral obligation (we, the world), and this is the same logic deployed in the Afghanistan and Iraq campaigns, a parody of self-defense masking a war against transparency. At the centre of this lies the lawyer’s anxious ‘I’, the weakened fulcrum of the whole war machine.

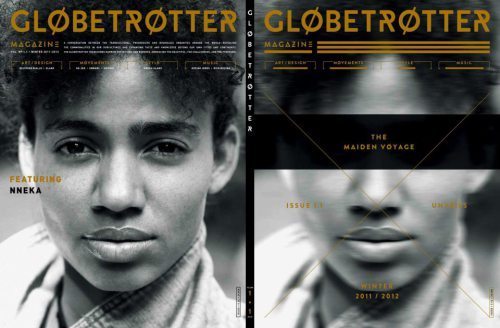

The magazine as Tumblr

Globetrotter is one of those vaguely defined, international, cosmopolitan culture and fashion magazines. With connections to Chicago, Lagos, and Jakarta, the magazine consists of an eclectic pastiche of commentary on various international trends organized into four sections: Art/Design, Movements, Style, and Music. The publication is the brainchild of Kennedy Ashinze and published through his company, Fuse Creative Agency. The articles contained in Globetrotter’s first issue cover a seemingly incongruous mix of topics.

These range from interviews with Franco-Senegalese artist, Delphine Diallo, and Gold Coast Trading Company’s founder, Emeka Alams, to an interview with the founder and CEO of Go-Jek, Indonesia’s first organized moto-taxi (ojek) service. Also included in the premier issue are interviews with Nigerian-German singer-songwriter Nneka and Chicago-based graffiti artist Slang. And hey, just in case you’re planning a vacation to Bali, Globetrotter has even provided its readers with its own insider’s guide to the island!

That said, while the magazine’s organizing logic may be a bit elusive, the content itself is often quite captivating. The art, interviews, fashion accessories, music coverage, and even advertisements that line the pages create a unique aesthetic that certainly does manage to maintain the reader’s attention. It is also important to note that the magazine is providing an outlet for many of these subcultural figures to get some coverage in print media form, since much of the publicity for many of them has been through online sources. Moreover, Globetrotter does, in its own way, present a fascinating study in global artistic and subcultural networks. It offers a medium through which conversations within and between different diasporas can take place and new creative endeavors can be shared and examined.

Overall, Globetrotter has plenty of potential and is certainly worth a read. I look forward to seeing future issues of the publication and watching the project come into its own.

* Steffan Horowitz, who joins the AIAC “collective” with this post, is a graduate student at Indiana University.

April 28, 2012

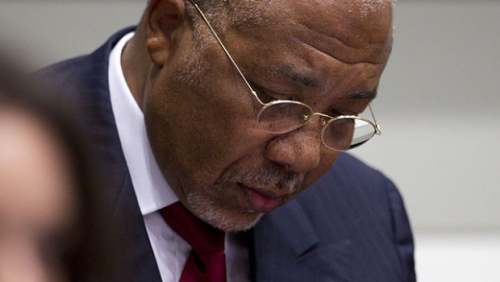

The Verdict on Charles Taylor–Take 2

Guest Post by Aaron Leaf

“Liberians decry ‘mockery of justice’ in Charles Taylor verdict” is a piece by Geoffrey York in Canada’s Globe and Mail that portrays a country outraged by the result of Taylor’s trial. The fact that Charles Taylor is reviled in the West but loved in Liberia is a fun thing to report on. It hints at the idea that Liberians have a very different world view, a mystical one where power is celebrated for its own sake, except it’s not really true.

At the Committee to Protect Journalists headquarters in New York yesterday, Liberian journalist Mae Azango was fetted over lunch for her daring stories detailing the harmful practice of female circumcision. She talked about the difficulties of being a woman in the macho world of Liberian journalism and the nasty backlash against her from traditionalists that caused her to go into hiding.

Afterwards she was asked her opinion on the Taylor verdict. She took a breath and thought about it for a while before structuring her story this way:

“Every Liberian was affected by Taylor’s regime whether they were harmed directly or lost friends and family,” she said. Taylor’s forces came to her house at breakfast time, looting their possessions and beating her father so hard in the back of the head with rifle butts that he later died. She would end up fleeing to the Ivory Coast. If the verdict keeps Taylor from returning to Liberia then she’s happy about it.

When I first moved to Monrovia and had colleagues and acquaintances profess their love for Taylor I was shocked, but it eventually got boring. Taylor supporters—posturing young men not old enough to have lived through war, greying NPFL partisans grasping at faded glory, former child soldiers messed up from years of trauma and drug abuse, boys and girls named after him (Charles and Charlsetta), relatives living off the money they made during his plunderous reign—made for a rather pathetic bunch. The common denominator was a love for Taylor’s enduring charisma and a belief in an international conspiracy to deprive Liberia of its rightful leader.

The longer I lived in Liberia, and the deeper my connections got, the more I heard different kinds of stories, private stories about grief and loss. Not for journalists.

A colleague, a man in his sixties, cried as he told me how everyday he prayed for his adopted father—”a kind and generous man”—whom “Taylor’s boys” had shot over something trivial.

A loud-mouthed sports reporter who I’d long taken for a Taylor supporter told me how, as a child, he’d watched as his older brother was killed and his liver eaten by rebels in the family kitchen. He could never forgive Taylor, he said. “Never never never.”

So when outsiders report from media savvy pro-Taylor rallies in downtown Monrovia and mingle with the crowds of men watching the verdict from tea shops and “intellectual centers”— overcaffeinated men in love with their own voices—it may not be very accurate.

What about the woman selling fritters across the street, or the Krahn laborer trying to avoid walking through the rally? Or all the people in the vast suburbs surrounding Monrovia that didn’t make make the trek downtown to share their opinions?

Like Mae, they may not offer you their views on Charles Taylor. If you ask and they choose to respond, it might be slow, considered and probably sad. This doesn’t make for good headlines. There’s nothing contrarian or weird about it.

The Verdict on Charles Taylor (Take Two)

Guest Post by Aaron Leaf

“Liberians decry ‘mockery of justice’ in Charles Taylor verdict” is a piece by Geoffrey York in Canada’s Globe and Mail that portrays a country outraged by the result of Taylor’s trial. The fact that Charles Taylor is reviled in the West but loved in Liberia is a fun thing to report on. It hints at the idea that Liberians have a very different world view, a mystical one where power is celebrated for its own sake, except it’s not really true.

At the Committee to Protect Journalists headquarters in New York yesterday, Liberian journalist Mae Azango was fetted over lunch for her daring stories detailing the harmful practice of female circumcision. She talked about the difficulties of being a woman in the macho world of Liberian journalism and the nasty backlash against her from traditionalists that caused her to go into hiding.

Afterwards she was asked her opinion on the Taylor verdict. She took a breath and thought about it for a while before structuring her story this way:

“Every Liberian was affected by Taylor’s regime whether they were harmed directly or lost friends and family,” she said. Taylor’s forces came to her house at breakfast time, looting their possessions and beating her father so hard in the back of the head with rifle butts that he later died. She would end up fleeing to the Ivory Coast. If the verdict keeps Taylor from returning to Liberia then she’s happy about it.

When I first moved to Monrovia and had colleagues and acquaintances profess their love for Taylor I was shocked, but it eventually got boring. Taylor supporters—posturing young men not old enough to have lived through war, greying NPFL partisans grasping at faded glory, former child soldiers messed up from years of trauma and drug abuse, boys and girls named after him (Charles and Charlsetta), relatives living off the money they made during his plunderous reign—made for a rather pathetic bunch. The common denominator was a love for Taylor’s enduring charisma and a belief in an international conspiracy to deprive Liberia of its rightful leader.

The longer I lived in Liberia, and the deeper my connections got, the more I heard different kinds of stories, private stories about grief and loss. Not for journalists.

A colleague, a man in his sixties, cried as he told me how everyday he prayed for his adopted father—”a kind and generous man”—whom “Taylor’s boys” had shot over something trivial.

A loud-mouthed sports reporter who I’d long taken for a Taylor supporter told me how, as a child, he’d watched as his older brother was killed and his liver eaten by rebels in the family kitchen. He could never forgive Taylor, he said. “Never never never.”

So when outsiders report from media savvy pro-Taylor rallies in downtown Monrovia and mingle with the crowds of men watching the verdict from tea shops and “intellectual centers”— overcaffeinated men in love with their own voices—it may not be very accurate.

What about the woman selling fritters across the street, or the Krahn laborer trying to avoid walking through the rally? Or all the people in the vast suburbs surrounding Monrovia that didn’t make make the trek downtown to share their opinions?

Like Mae, they may not offer you their views on Charles Taylor. If you ask and they choose to respond, it might be slow, considered and probably sad. This doesn’t make for good headlines. There’s nothing contrarian or weird about it.

April 27, 2012

Sierra Leone Independence Day

Freedom Day in South Africa. Togo Independence Day. And Sierra Leone’s 51st Independence Day. That’s all today. We’ve been celebrating Freedom Day with music elsewhere today. So this post is for Sierra Leone. My current favorite song we played last week but there’s more: a Bajah and Dry Yai Crew song:

Refugee All Stars released an album this week:

Sierra Leoneans are active in the diaspora too. Like Janka and the Bubu Gang:

Or Shady Baby:

And a classic for an election year:

You’ll tell us what your favorite Togolese tunes of the moment are in the comments.

The verdict on Charles Taylor

Guest Post by Mats Utas

Yesterday the Special Court for Sierra Leone found Charles Taylor guilty of aiding the RUF during the Sierra Leonean Civil War. The court case that has taken five years is the last of a court that has previously sentenced 9 Sierra Leonean rebel and military leaders with long prison sentences. Taylor has 14 days to appeal and his sentence should be given on May 30. Not too long ago I was in a Monrovian bar owned by a friend of mine. I complained about a drink where they used American ginger beer instead of making their own “local” version. Local ginger beer is a sweet, nice and affable drink compared to its unpleasant American brother. Nothing comes out of complaining so instead I arranged with the barman that he should buy some ginger and lime and we would meet before opening the following day. So we did and together we made ginger beer and with the skills of the barman created a very tasty drink. We named it CT after Charles Taylor. Charles Taylor was often nicknamed ginger because of his light skin. I hope that costumers ordering a CT do understand that it is an irony – the name was not given to celebrate Charles Taylor, but as a comment on the enigmatic presence of Charles Taylor in Liberia close to ten years after he left the country in 2003.

During the heydays of Taylor, but I would say less today, Liberians used the word “wicked” in almost every sentence. Everything was “wicked”. You could be wicked in the ordinary negative sense, but to show appreciation for a new pop song people would typically say “e wicke”. I would describe Taylor with this ambivalence. Nobody would deny that Taylor was a WICKED man; responsible for nightmarish atrocities, systematic killing, extreme destruction of infrastructure and looting of property. Outlandish was the fear that many people felt for him and his security forces at the time when I lived in the country 1997-98. Still many thought he was a rightful leader. He was strong and controlled people, he took good care of his “pepper bush” – his people; he was wicked with ambivalence. People were getting more than a bit tired of him when the war started anew, but when he was forced into exile in 2003 by a combination of LURD/MODEL military pressure and pressures from the international community, and subsequently brought to court in Sierra Leone in 2006, many Liberians started to view him as a hero, someone who stood up against what they perceive as an international conspiracy.

We need to keep this ambivalence in mind now when Taylor is going down. Yesterday I got this report from Ilmari Käihkö, a doctoral student of mine who is currently in Monrovia for fieldwork:

The night before the Taylor verdict came out was calm in Monrovia. Some members of Taylor’s National Patriotic Party held a meeting, but my informants could not positively confirm whether this was connected to the verdict or not. Long after nightfall a loudspeaker car was touring the suburbs, broadcasting a message that Taylor is innocent and a victim of an international conspiracy. I woke up twice to this message, but have heard it a hundred times since I came to Liberia almost two months ago.

There is something paradoxical about how the people I’ve met here and the people abroad think about the former president Taylor and the incumbent president Sirleaf. Whereas Sirleaf enjoys broad international support, her support among the Liberian grassroots is meager. The situation for Taylor is exactly the opposite. If he could have participated in the November presidential elections he would have won by a landslide. The fact that even most of the rebels from LURD and MODEL factions – who fought against Taylor in the second Liberian civil war from 1999 to 2003 – state that they have nothing against the man and that they would like him to be freed. Before coming to Liberia I had no idea that this was the case.

Of course not everyone likes Taylor, and even many that like him privately said before the verdict came out that they hope that he would not be freed. After the verdict came out a rainbow was sighted above Monrovia. While far from an uncommon sight above the capital city after it has rained, some thought that this was a sign from god: some suggested that perhaps the higher power was happy of the verdict? But others pointed out that a rainbow also appeared at the time when President Tolbert was executed in 1980. (Monrovia, April 26, 2012).

Even the rainbow is ambivalent. I also think that people within the old pepper bush of Taylor have this ambivalent feeling; on the one hand they know that they have lost their Big Man, but on the other hand their waiting is over. Now they need no longer to fear their leader’s return, now they can go ahead with their business. And indeed some of the strongmen under Taylor are sitting on a lot of his money. With Taylor in safekeeping they are now free to spend their wealth in ways which they themselves like. In the same way some strongmen have not really showed political color out of fear, but this may very well happen now. Most Liberians whether in support of Taylor or not will now be relieved. That Taylor will not return to Liberian soil is certainly a step towards improved stability. If he would have been released, on the other hand, the ground would again have started to shake.

So we talk about Liberia, but the court ruling was for war crimes in Sierra Leone. What does the verdict mean for this country? I lived in Freetown between 2004 and 2006. People constantly talked about the Special Court for Sierra Leone as a waste of money. They were not very impressed with this version of justice. And of course it was hard to establish its significance in the country after the disappearance of AFRC leader JP Koroma, and the deaths of RUF leader Foday Sankoh and CDF leader Hinga Norman. The nine others arrested and subsequently sentenced to long prison terms were of less importance. For the SC-SL the high profile case of Charles Taylor was a way of establishing their significance. When Taylor was caught in Nigeria and brought to court he was briefly taken to Sierra Leone and the SC-SL complex in Freetown before transferred to The Hague. It was seen as a security risk to keep him in Freetown (and evil voices say that the Western lawyers at the court did not look forward to spending another few years in Freetown). Taylor’s brief stay in Freetown rendered some interest by Sierra Leoneans who wanted to catch a glimpse of that strong leader, but it is rather clear that most Sierra Leoneans have had problems to see the link between Taylor and the Sierra Leone war as significant enough. Indeed most would state the obvious that ties were close between Taylor and the RUF, but that he would be amongst those most responsible for the war in the country has been hard to grasp or believe for a majority of the population. It is questionable if the verdict against Taylor will change this.

So although many Sierra Leoneans will think that the region is slightly safer without Taylor they will, if they do, celebrate yesterday’s verdict because the SC-SL have helped them to rewrite their own history and because it is much easier to cast the blame on somebody outside their own society. (I think the scattered reports of positive responses accounts for that.) In the meantime the court case against Taylor has since 2006 up until today cost somewhere between 30 and 40 million US dollars annually. I can’t count how many Sierra Leoneans who were enraged over the high costs of the SC-SL. The court was in the minds of the people a symbol of how Western aid money was misappropriated. Why was it not combined with an effort to strengthen the Sierra Leonean legal system, why was it put up as a parallel structure to the Sierra Leone courts? Well when the court now closes some of these questions will rest, and with Taylor locked up Sierra Leoneans and Liberians can sleep a little better at night.

* Cross posted from Mats Utas’s blog.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers