Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 544

April 4, 2012

'Africa's first openly transgender music star'

African governments don't want us thinking that "homosexuality" is within the realm of their "traditional values". So apparently these leaders, even Nobel Peace Prize winning ones, use that as an excuse to justify the persecution and lack of protection for some of their most vulnerable citizens. Well, it seems that the Angolan government who currently seem to have their hands full (of money?) can't be bothered to check whether or not popular Kudurista, Titica, fits within that value system… and we're glad for that. Now, I don't know the frame through which Angolans are seeing Titica. A little forum and youtube scrolling reveals a divided public (as always). Since I'm not there, I'm not going to write a drawn out post on LGBT issues in Angola. I do have to say that Titica may just be as much of a "challenge" for New York audiences as ones in Africa, so I'm proud to say that she will be visiting us next Monday night at Bembe in Brooklyn for the iBomba party! New Yorkers, come say hi and give your support.

(Hip Hop seems to be the realm for political protest in Angola, while interestingly, previously marginal Kuduro seems to be turning into a sort of symbol of national pride. Whether or not that translates into better living and working conditions for the scene's artists and producers remains to be seen. But apparently Angola has seen this kind of thing before.)

Everyone else look out for more content and coverage of her visit soon.

The Road Down to 'Africa'

I never understood why E-Type's 2002 smash hit 'Africa' didn't really catch on outside Sweden. The video is slightly embarrassing. It's like watching a Scandinavian version of the b-grade movie 'Soul Plane.' But it has its tongue firmly in its cheek. Or so one hopes.

[Eller hur?]

April 3, 2012

If Africa really is "a country" …

If Africa really is "a country" for many Americans, then that country is somewhere few outside the military have even heard of … Djibouti: AFRICOM (much of it apparently run out of a rural base here in Britain), drones-ville, the only Japanese military base in the world outside Japan, the EU's anti-pirates clogging up the port, luxury swimming pools and bars. Throw in the Chinese Navy, mix with the still-smouldering fag-ends of the French empire, all sorts of private military outfits now cashing-in on the anti-pirate boat-protection (insurance) racket, some significant slices of both Somali and Dubai capital, add the entirety of Ethiopia's imports thundering the place … stir at 40o celsius.

Photo Credit: Matthieu Paley

Disco Angola (in New York City)

Stan Douglas. "A Luta Continua, 1974" (2012)

The photographer Stan Douglas's new project "Disco Angola," a work in progress, is on display at the David Zwirner Gallery in New York until April 28, 2012. The New Yorker announced the show in Goings on About Town with the image above. What's amazing is that Douglas has not been to Angola, though from what I read in this interview with Monica Szewczyk he has done a good bit of studying up.

Here are some of the photos from the show which puts, as Douglas describes it to Szewczyk, postcolonial Angola and postindustrial New York in visual touch, makes capoeira and kung fu "visual rhymes." I think he is on to something.

He's particularly interested in the 1970s and New York's disco scene, with the dynamics of intervention staged there, the erasures and standardizations that resulted and similar processes staged in Angola during the Cold War. Read the interview, it's worth it. It disappoints only when Douglas says that he's been discouraged by travel guide writers from going to Angola where, they told him, nothing of the '70s remains…hmmm.

The photo "Exodus 1975 (2012)" is clearly inspired by the Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuscinski's slim but arresting text 'Another Day of Life' (1976) about the last weeks before the declaration of independence in Angola and the exodus of Portuguese immigrants:

[image error]

Stan Douglas. "Exodus, 1975" (2012)

But it also wants to trouble the notion of witnessing and the truth of photojournalism. Douglas calls this work "costume drama in fragments." But I wonder if he knows that Angolans in the '70s wore bell-bottoms, watched Kung Fu films and also listened to Manu Dibango as did the underground disco spinners in NYC he mentions? So much refraction and reflection in so many directions.

Nawal el Saadawi on Egypt's Revolution

The current issue of Bidoun magazine features a very timely conversation with Egyptian feminist Nawal el Saadawi. Her view that "nothing has changed" in Egypt since January 25 of last year and her contempt for the co-optation of the revolution from all sides are views many other Egyptians share. Her singling out of Wael Ghonim is especially relevant. Ghonim recently appeared in Los Angeles as part of the ALOUD series of the Library Foundation of LA (which charged $20 per ticket, mind you), and somehow managed to simultaneously perform humbleness and assume the role of official Egyptian spokesperson with a straight face (a video of the event is included in the link above).

Is there any opposition you can believe in?

I am going mad. There is no opposition. The political parties like Wafd, Tagammu, and the Nasserites, they are all working together. It seems that I am the only one who is outside of all that mess. Do you feel that? Do you agree with me?

I am with the young people but the young people are divided. I read yesterday that Wael Ghonim is writing a book about the revolution and taking two million dollars as a fee! I am the one writing for forty years and translated into so many languages!

Here is another excerpt from the conversation (the rest of which is available here):

Tell me about anxiety. Are you anxious?

Today I am worried. I am not scared. I have immunity to fear. I am worried about the revolution. I feel that we are fighting big powers, America and Israel. And Saudi Arabia is paying billions of dollars to Salafists and fundamentalists so that we would say, "Oh, Mubarak, we need you." It is all planned to bring the old regime back. Everyone is talking about the insecurity… Oh, the insecurity, the insecurity, we need security so that the business people will come and the foreign capital will come.

But we are not beggars to take US aid. We need to produce our own food. We need agricultural production, intellectual production. We have millions of young people ready to work, but no one wants them to work! We import ful medames from California. I eat ful from California! We import bread from California. And wheat. The textile factories — the best textile factories were closed for the benefit of what they call the free market. This is colonialism. We drink Israeli beer. They are replacing Egyptian production with American-Israeli production.

And the fruits! We once had the best fruits. Now the vegetables and fruits have no taste. None. I cannot eat a simple salad! I am worried. I have been fighting since King Farouk. And I am still censored by the media. Why does the media continue to try to make me quiet?

This is what makes people say I have afkar moayena. Like the doorman downstairs, or that stupid magazine.

I don't care. I am eighty years old. I have been struggling since I was ten. Since I was a child I have dreamed of this revolution. I am disgusted. We don't have good lawyers and judges who can be really fair. The judges will be against me in the end. Because they are religious and with the mainstream.

"We were colonized, and that is why we are funny"

The current issue of Bidoun magazine features a very timely conversation with Egyptian feminist Nawal el Saadawi. Her view that "nothing has changed" in Egypt since January 25 of last year and her contempt for the co-optation of the revolution from all sides are views many other Egyptians share.

Her singling out of Wael Ghonim is especially relevant. Ghonim recently appeared in Los Angeles as part of the ALOUD series of the Library Foundation of LA (which charged $20 per ticket, mind you), and somehow managed to simultaneously perform humbleness and assume the role of official Egyptian spokesperson with a straight face (a video of the event is included in the link above).

Here is an excerpt from the conversation (the rest of which is available here):

Tell me about anxiety. Are you anxious?

Today I am worried. I am not scared. I have immunity to fear. I am worried about the revolution. I feel that we are fighting big powers, America and Israel. And Saudi Arabia is paying billions of dollars to Salafists and fundamentalists so that we would say, "Oh, Mubarak, we need you." It is all planned to bring the old regime back. Everyone is talking about the insecurity… Oh, the insecurity, the insecurity, we need security so that the business people will come and the foreign capital will come.

But we are not beggars to take US aid. We need to produce our own food. We need agricultural production, intellectual production. We have millions of young people ready to work, but no one wants them to work! We import ful medames from California. I eat ful from California! We import bread from California. And wheat. The textile factories — the best textile factories were closed for the benefit of what they call the free market. This is colonialism. We drink Israeli beer. They are replacing Egyptian production with American-Israeli production.

And the fruits! We once had the best fruits. Now the vegetables and fruits have no taste. None. I cannot eat a simple salad! I am worried. I have been fighting since King Farouk. And I am still censored by the media. Why does the media continue to try to make me quiet?

This is what makes people say I have afkar moayena. Like the doorman downstairs, or that stupid magazine.

I don't care. I am eighty years old. I have been struggling since I was ten. Since I was a child I have dreamed of this revolution. I am disgusted. We don't have good lawyers and judges who can be really fair. The judges will be against me in the end. Because they are religious and with the mainstream.

Film: The talented Tajdin sisters

Filmmaker Amirah Tajdin and her producer sister Wafa Tajdin are currently working on their first feature, titled "Walls of Leila," and are running a Kickstarter campaign to help launch their production. For two young, clearly talented filmmakers, this is a film project worth backing. You can visit their kickstarter page here. The film is described as "… a love story set in Cape Town South Africa that chronicles the life of Leila, a young Cape Malay girl who falls in love with an American boy, Derek, who happens to be black. When the intricacies and prejudices of race and religion (which are still very prominent in postcolonial Cape Town) throw Leila off balance, she finds herself forced to make difficult decisions as well as questioning her own degree of prejudice. She is ultimately caught between breaking the hearts of her family and/or her lover." The trailer reminds me a bit of what Andrew Dosunmu visually achieved with "Restless City":

We get a sense of the Tajdin sisters' talent in another short they made as part of the CollabFeature Project, a brilliant initiative that brings independent filmmakers from all around the world to collaborate on multi-director feature films.* Tajdin's contribution to the feature, 'Train Station' (working title), where 40 filmmakers in over 26 countries submit their section of the story (filmed in different international cities), is set in Nairobi:

A lithe, majestic drag queen sits in Nairobi's train station, perfectly framed by the station signs behind. Rusty, worn colors and once imperial gold-painted signage remind of the colonial times past; few places in downtown Nairobi retain the withered gleam of colonial architecture so much as Nairobi station, that's remained nearly unchanged save for its inevitably dusted decay. Perhaps then, it's truly the perfect setting for this drag queens poetic breakdown.

Sitting on a bench, smoking a cigarette, the film witnesses the drag queen's poetic pandemonium; both self and body are stuck in the railway station's no man's land; "I'm stuck between where I'm supposed to be and where I am" — both a lament on his/her body, and a literal comment on the act of waiting at a train station, and the self-reflection waiting induces. Amirah Tajdin deftly melds the now iconic familiarity of Nairobi station, with the odd-beauty of the drag queen, playing on the expected and unexpected.

In Swahili, a woman observing the drag queen's breakdown leans over and says, "whoever he is, he's not worth your tears". And again, in just 8 short minutes, Tajdin plays on our preconception of Kenyan prejudices toward homosexuality. It's very well made, and the visuals often carry the short narrative along, particularly when the drag queen's anguished soliloquy tends toward confusion.

* Filmmakers can join the project and contribute their own sections. See here for more details.

April 2, 2012

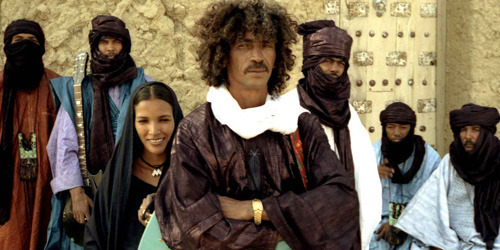

Tinariwen speaks on the coup in Mali

Tuareg musicians Tinariwen, on tour in Europe these days, spent some time in Belgium this weekend. Belgian public broadcaster VRT [they'll do a feature on Mali blues once a year, usually at the end of June, covering the one high-profile 'world music' festival Brussels has in summer, squeezing them into a one-minute slot alongside performers from the Balkans, a visiting Soukous star, a French rapper and a Jamaican reggae artist] asked Tinariwen members Abdallah ag Alhousseini and Wonou Wallet Sidati what they made of the coup in Mali. It's a short but useful video interview since most of what we get to read in international media over the past weeks are translations of and interviews with the military commanders of the coup, and then some other wires by foreign journalists based in Bamako. I haven't read much reports coming from the north, i.e. from the Tuareg front. Below's a brief translation of the VRT's interview with Tinariwen's guitarist and singer:

Abdallah: Our music was created under the same circumstances as the American blues. It was created in exile. We've been living for years as exiles between Algeria, Libya and Niger since the 1960s until 1990.

Wonou: Our people have been dying because of bombardments by the Mali army. They're nomads. Not rebels. People who have nothing to do with the war. They don't make war.

Abdallah: The Tuaregs want independence. This is nothing new. We've wanted this since the French have left. For thirty years we have big problems: we don't have hospitals, schools… We don't feel Malian. We live under the same [Mali] flag, but we don't consider ourselves true Malians. (…) The coup in Mali serves us because the people will start looking at Mali. They will direct their attention to Mali and see what's happening there. People will start to understand Mali's reality. Many people knew what was happening there but closed their eyes to it. (…) From Timbuktu to Gao, the border between Niger and Algeria … that is our country, that is our territory, that is where our families live. That belongs to us. We're not colonizing anything; we have been colonized ourselves.

Asked about the Libya-Gaddafi-Al Qaeda-Tuareg connection:

Wonou: We're not bandits. We're not terrorists. We're a people who claim their rights. Our rights have been ignored for more than 50 years by the Malian state. Our people fighting there right now are no Al Qaeda people. It's true that some among them have returned from Libya, but they just returned to their homes. They were born in our region, left, and have now returned.

Abdallah: Our cause is here, now, and it's a cause that won't go to sleep.

If you've been following Tinariwen and reading (or listening to) their lyrics, this doesn't come as a surprise.

What was new to me though, were the numbers cited in the VRT program's debate after the interview. Estimates are that Libya returnees joining the Tuaregs' ranks numbered less than 200 (some of the Gadaffi soldiers also joined the government's army before the coup), bringing along their weapons, but apparently enough to defeat the 7000 men strong Malian government army — and take over half of the country (including Timbuktu and Gao).

Cheikh Amadou Bamba Day

For over two decades, West African Muslims from the Murid Sufi Brotherhood come together at the annual Cheikh Amadou Bamba Day march in Harlem, New York. Scholar Zain Abdullah calls it "a major site where they redefine the boundaries of their African identities, cope with the stigma of blackness, and counteract an anti-Muslim backlash". Mamadou Diouf (in his preface to 'A Saint in the City: Sufi Arts of Urban Senegal') considers Bamba's message an "unfinished prophecy". Above and below are photographs Marguerite Seger took during the parade in July 2010.*

* Marguerite Seger is a New York based photographer of Sri Lankan and French decent, born and raised in Sweden. Her photography, she writes, "is versatile yet with a strong personal style". Seger has exhibited regularly the passed years both in solo and group shows. She describes her work as "urban, raw, yet romantic", shooting anything from MMA fighters to jeans ads, music videos, boxers and short films. More of her photographs here and here.

The Hissène Habré "political and legal soap opera"

Guest post by David Styan

In recent weeks media coverage of African criminals and their victims have been dominated by capture (Kony) and conviction (Lubanga), largely overshadowing the latest twist in the most comprehensive and longest-running African legal case, that of Chad's Hissène Habré. His crimes — the torture and extra-judicial killing of tens of thousands of Chadians during his presidency between 1982 and 1990 — and his ability to evade prosecution for so long, speak loudly of African leaders' attitudes to punishment and impunity.

The case against Habré and his aides appears straightforward. Crimes were fully documented by Habré's own security services, whose records are intact. Further extensive oral and documentary evidence was gathered by Chad's own enquiry, completed in 1992. For twenty years, associations of victims of Habré and Chadian lawyers, have tenaciously lobbied for justice.

Courts in Belgium recently hosted the latest twist in what Desmond Tutu has castigated as Africa's "interminable political and legal soap opera." Twenty years after charges were first filed, the International Court of Justice will pronounce in coming weeks on whether Habré may be extradited from Senegal for trial in Belgium. If so it may end years of prevarication, by lawyers and politicians in Dakar and within the African Union, which declared Senegal should try Habré in 2006.

The defeat of Abdoulaye Wade as Senegal's President may also dent Habré's de-facto political immunity. Habré has been able to purchase protection while living comfortably in Dakar. When preliminary legal proceedings began a decade ago, he hired Senegal's top defense lawyers. Two of these were subsequently appointed to the cabinet of President Wade. While the support of both the Minster of Justice and Minister of Foreign Affairs has been useful insurance against extradition, the same level of protection may not be guaranteed under the new President.

Not guaranteed either is the attitude of Habré's successor, Chad's current president Idris Déby, who himself knows a thing or two about political violence and impunity, clear. He has said he would like Habré tried, yet worked alongside Habré throughout the 1980s. Impunity easily outweighs accountability in a state held together in part via fear and patronage, key themes in the films and screams of Chad's leading artist, Mahamat Saleh Haroun.

* David Styan, an occasional contributor to AIAC, is a lecturer in politics at Birkbeck College, London.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers