Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 546

March 28, 2012

Found Objects N°21

German singer-songwriter Joy Denalane (born to a South African father who's a cousin of Hugh Masekela) recorded her song 'Im Ghetto von Soweto' twice. I prefer the original, less explanatory, German version (a tentative translation of which I'm including below) to the later English adaptation (rewritten for an international audience, I assume — it has some extra lines at pains to explain why, for example, one of the figures in her lyrics was detained). Masekela himself also contributed to the song and features in the above video they shot in Soweto in 2003, mixing it with archival material.

This is auntie Jane's house

When the first shots were fired

Come in quickly, my child, and don't cry

Lie down on the kitchen floor

This is Orlando West

in June 1976

See the school kids run

The boy Pieterson

The police are shooting them

A stone flies, a shoe drops

A car burns, a child runs

Images everyone here knows

When the brown dust settles

What remains is the grey smoke in the air

In the ghetto, ghetto of Soweto

This is auntie Nancy's house

She wanted to do Karabo's laundry

He nearly missed the train in the morning

She pulls his pass from his jacket's pocket

'84 in Diepkloof

It's already been a week

Did anybody see whether they took him

To prison at John Vorster Square?

They stopped him, he doesn't have a pass

They took him, and put him in jail

Only now did she find out

When the red dust settles

What remains is the brown smoke in the air

In the ghetto, ghetto of Soweto

It should have been a day of joy

At auntie Eve's house

The daughter gave birth to a child that night

But both are lost

They are positive

In Moroka, Pimville, Dube…

No house is safe

They battled apartheid but then came Aids

And they fight it in 2002

It used to be TBC from the mines

Today they're infected with HIV

I'm talking about every second pregnant woman

When the brown dust settles

What remains is the grey smoke in the air

In Soweto

Stands Auntie's house…

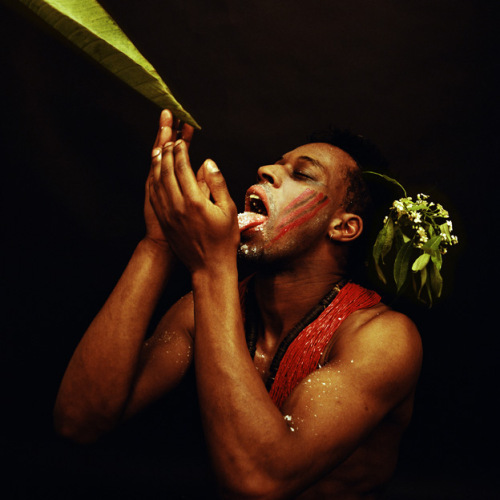

Nothing to Lose? The art of Rotimi Fani-Kayode

Rotimi Fani-Kayode's first solo show in New York opened last week. The British-Nigerian artist's last works, large photographs of the naked male body, are on display at the Walther Collection in New York City. These are images of rites which explore the artist's familial background as keepers of the shrine in Ife, Nigeria, and the artist's status as liminoid. Fani-Kayode's interest in Yoruba 'techniques of ecstasy' is juxtaposed against a sombre thinking into sexuality, race, and religion, as discourses of the body.

The artist's position in relation to these discourse is quoted in the exhibition notes:

On three counts I am an outsider: in matters of sexuality, in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for [...] Such a position gives me the feeling of having very little to lose.

If his cultural exile, and sexual identity as an 'artist with a sexual taste for other young men' designated him, working in the 1980s, as an outsider, his art takes aim at a genealogy of canonized outsiders.

Fani-Kayode studied in America, at Georgetown and the Pratt Institute, and this work strikes the Westernized eye as an intervention in the tradition of Catholic image-making by painters such as Caravaggio; other works engage with Francis Bacon and Édouard Manet.

Fani-Kayode's work with his partner Alex Hirst okayed an important role in art's response to the AIDS epidemic, in their series 'Ecstatic Antibodies' (presented in a 1990 group exhibition of the same name). The artists described the aim of this work as "the 'alchemical' or 'ritual' production of spiritual antibodies". This ambition — constructing aesthetic edifices eluding to elusive protective veils — is most closely contemporary to the work of queer artists such as David Wojnarowicz and filmmaker Derek Jarman; the staging of quasi-religious scenes are reminiscent of Jarman's queering of Genesis, The Garden (1990).

The artist recognised early on that his sexuality constituted an obstacle between himself and his Nigerian background: "a certain distance has necessarily developed between myself and my origins." America and England of the 1980s did not offer a perfect haven from discrimination, and AIDS exposed latent hatred and discrimination.

Despite this wealth of context, it would be useful to know more about how this work is founded in personal and inherited memories of Yoruba culture, and its performances and image-making. Those traditions are certainly there, not just in the eye of the critic looking for "Africa", but in novel and challenging forms, bent for new realities. Kobena Mercer's essay comments on the need for more insight into this dimension, suggesting that comparison to the queer American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, obscure Fani-Kayode's 'disparate' influences. Mercer claims that the work is 'overturning the dead weight of modernist primitivism in the process of such cultural bricolage'.

Bricolage, however, suggests an amateur, indifferent in his borrowing from a variety of sources. The bricoleur is the classic wanderer without an investment in any one place, weighted down by the effluvia of each place he's visited: noisy, untidy, on the margins. In weaving together multiplicity, Fani-Kayode's work places him within that tradition of bricolage. But his work also does far more than offer us a simple, clanging collection. Instead, it places the body in a series of positions which juxtapose the norms of different societies, and their sexual and spiritual practices. As a queer artist who existed between two societies, both of which variously neglected and ostracized the queer body, these positions he takes on in his work are by no means indifferent. Fani-Kayode died in 1989, aged 34. The work completed by that point suggests the mature career of this artist is a real loss.

March 27, 2012

The (very unpopular) Nigerian finance minister who wants to be President of the World Bank

Yesterday the African Union added their backing to Nigerian finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala's run at becoming World Bank President. She announced her candidacy on Friday, just hours before Obama told everyone he'd picked South Korean-born rapper Jim Kim (now backed by Paul Kagame). But how do Nigerians look at this? Some are puzzled by the government's silence, and local media reports that Ali Mazrui wrote to President Jonathan urging him to offer louder and stronger support to Okonjo-Iweala's campaign.

There are also those who would be pleased to see her get the job simply so that Nigeria could be rid of her. Dubbed "Okonjo-Wahala" (wahala means "trouble") and accused by opponents of acting as an agent for global financial instutions, she was widely seen as the instigator of the removal of the fuel subsidy in January that led to the eruption of the Occupy Nigeria movement (when she became very grumpy indeed, took to twitter and got a bit of a kicking). The poet Odia Ofeimun says she wouldn't have had to return to Nigeria if she'd been able to finish the job of ruining the economy first-time around when she worked for Obasanjo.

It's great that a Nigerian woman is in the running for such a prominent job, and I'd pick her over Jeff "Yawn" Sachs and crooked Larry Summers any day. But it's pretty hard to get enthusiastic about an anti-corruption politician who hates anti-corruption campaigns so much and seem to distrust poor people so much.

What has also gone undiscussed is the fact that Okonjo-Iweala was put forward by a bloc of African "superpowers" comprising Nigeria, South Africa and Angola, which isn't really such an obvious grouping when you think about it. Sure, they're all considered "emerging African economies" but they're also fierce competitors. Has this triumvirate made international diplomatic moves like this before or is this a new thing? What other issues might bring these three together in future? Do the three countries' interests actually line up behind Okonjo-Iweala's candidacy or is this part of a longer-term powerplay to tip southwards some of the power vested in global financial institutions?

So what's the verdict, people? See you in the comments.

Music Break. Szjerdene

Londoner Szjerdene's Blue Lullaby. Her music is produced by Glenn Nichols, while the video was made by Saul & Josh.

'Really you're African?'

Filmmaker Shola Ajayi (she's also a media studies student at The New School in New York City) is one of the people behind this humorous, but sharp, web series on "the African experience in America." The point behind is to "refute negative portrayals of Africans in the media but it will also work as a window into the lives and traditions of individuals from different parts of the continent of Africa." Here's a link to the trailer and below we've embedded the first three episodes. The first features Olajuwon Ajayi (Shola's sister?) and people messing up her name. The second video includes the question, "Really you're African?" to a Ivorian who people confuse for someone from the Caribbean.

And here are links to episode 4 and episode 5.

For more information, see the series website, its vimeo channel where you can watch newer episodes and on soundcloud for audio interviews.

March 26, 2012

Mali's coup — 'Politics is bad'

Columbia history professor Gregory Mann writes the second of his of posts (here's the first) on last week's military coup in Mali for Africa is a Country:

"Politiqui mayni," sing Amadou and Miriam, "Politics is bad." No kidding. But sometimes it's worse than others, and sometimes it's needed. In order to think clearly about Mali's confusing coup, we need a little politics, now more than ever. Where I'm from, we call this the hair of the dog. In this case, a little historical perspective wouldn't hurt either.

The first step is asking the right questions. The idea that because the coup happened, it is no longer worth taking positions on it is wrong-headed and dangerous. Now is the time to ask why, and why now.

Obviously the rebellion in the North counts for a lot. Corruption and malfeasance do, too. And, somewhat paradoxically, so does the fact that presidential elections were scheduled for next month, elections for which the incumbent, Amadou Toumani Toure ('ATT'), was not a candidate.

ATT's record was mixed at best. There's lots to criticize — rising crime, deepening inequality, systemic corruption, narco-trafficking at the highest levels… and above all the disastrously passive response to the rebellion in the Sahara (which is too much to go into here). People who live in the affordable housing units he sponsored — the 'ATTbougou' phenomenon — might see a brighter side. But the question of whether or not ATT's government succeeded is the wrong question to ask. Ditto the question of whether he might come back to power. The real question is when the junta will leave it, how, and at what cost. That's the million dollar question, and those of us on the outside ought to be listening for its answer.

That said, some other things might seem confusing. They aren't.

First, did corruption cause the coup? The junta says it is down on corruption. So is every Malian I know. Who isn't, at least in public? And which junta in the last twenty years or more hasn't said it would stamp out corruption? The novelist Moussa Konate wrote a strong piece in Jeune Afrique condemning the fact that the Malian state "became the private property of the political class and its accomplices." True. But that's been true for several years. The rot in the Malian state, from roots to branches, didn't cause it to fall, it only allowed it to.

Second, Captain Amadou Sanogo, the leader of the junta, says he wants to get Mali's democracy back on track. Did this noble cause inspire the coup? After all, the junta calls itself the "National Committee for the Re-establishment of Democracy and the Restoration of the State". But just because they used the word 'democracy' doesn't mean these soldiers are democrats. Seriously. Moussa Traore's crew (1968-78) was the Military Committee for National Liberation — and the 'L' didn't stand for much. Neither did the 'D' in the Democratic Union of the Malian People, the single party that succeeded it (with Traore at its head), from 1978-1991. With elections scheduled for a month from now, this coup was not meant to re-establish democracy, but to de-rail it.

Third, some have argued that because people in Bamako have not taken to the streets, the coup has popular support. Not so fast — people didn't take to the streets to support it either, unlike during Mali's two previous coups (1968 and 1991). This might be because the situation was (and is) so unclear, but honestly it is hard to know what level of support the junta has (no matter how unpopular ATT might have become). Whatever the reason for Bamako's relative quiet, Monday was the 21st anniversary of the coup that briefly brought ATT to power before he handed it over to a popularly elected president, until being voted into office himself in 2002. It is a national holiday, and on this occasion reports have it that as many as 1,000 people marched from the Bourse du Travail to the television studios to demand a return to constitutional rule. They disbanded, their point made. But no one should assume that was the last march, or that 'the street' will be quiet forever.

Other movements are afoot. On Sunday, the leading political parties — in fact, almost all the political parties — met to establish a united front to demand that the soldiers give their democracy back. And the government ministers, party leaders, and presidential candidate who are being held without charge announced a hunger strike to demand their release and a return to civilian rule. Over the last few days, two of the top contenders in the presidential race — Ibrahim Boubacar Keita and Soumaila Cisse — condemned the coup in no uncertain terms, one just before the other. They are politicians, and they know which way the wind blows. As a wise man once said, you don't need a weatherman for that.

Looking back on Occupy Nigeria

Nigerian producers Chris Dada and Funmi Iyanda created chopcassava.com "to document the popular fuel subsidy protests in Lagos." They have now stitched together their "short viral films and video-blog diary, made by a team of volunteers and first uploaded during the protests."

The result is a useful retrospect, compiling images and recordings we (following ChopCassava closely) have watched and linked to while trying to understand the protests and its ramifications. What ChopCassava's reporting made increasingly clear was, indeed, as one of the voices in the documentary argues, that what started as a protest against the cutting of fuel subsidies, morphed into a movement rallying around the question about "the way how we are governed as a people".

The dancing Senegalese man

Senegal voted this weekend. Abdoulaye Wade is gone after 12 years. Macky Sall, once Wade's protege and variously prime minister and minister of mining under the old man, is now in charge. Only Senegal's fourth President since independence in 1960. So not a clean break with the past (though the two did fall out over the role of Wade's son Karim in government affairs). We hope to have a few post election analyses posts up in the next few days. Till then enjoy the exuberance of "the dancing man" filmed (with a cellphone?) by Al Jazeera journalist Azad Essa in Dakar last night.

Soweto Soul

What better way to start the week than with some a cappella soul courtesy of South African singers Buhlebendalo Mda, Luphindo Ngxanga and Ntsika Fana Ngxanga (better known as 'The Soil').

March 25, 2012

#Kony2012 is a Mixtape

It's been interesting to see how Kony 2012 went from being a viral campaign (the biggest in history?) to an internet meme, to a self-fulfilling parody. And now it's an experimental Afro-glitch album by someone only known as Jose Ph. Kony. While the beats are pretty decent, one can't tell if this is purely an opportunistic release or meaningful satire. Cleverly sampling audio from the Kony 2012 campaign video as well as a critical Al Jazeera report, and track titles such as "Lowest common denominator activism and necro-politics", do suggest some kind of critical engagement. Nothing too heavy though. Listen to 'Kony 2013′ here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers