Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 548

March 22, 2012

The coup against democracy in Mali

From a writer friend:

Here's video of the coup announcement in Mali. Ridiculous. The screen is dark at first — they were having technical difficulties — but the image appears after 30 seconds or so. See the scene. As for the speech, it's the usual pompous nonsense, poorly delivered by a junior officer out of his depth.

From a Malian friend:

In the last couple of hours, power has been usurped for a second time in our history by the military. They have overthrown the democratically-elected incumbent president who had a month left in office on his second and last term. We were preparing to vote on scheduled presidential elections in April …it's a crushing blow to the democracy we built since the 1991 revolution which was won with the blood of 300+ students, trade union leaders and citizens protesting the 23 years of military rule of General Moussa Traore.

And here's the second declaration, a short time ago. This one is briefer and given by Capt Sanogo who is the head of the junta:

More later.

March 21, 2012

African art is a 'gutted whore-house'?

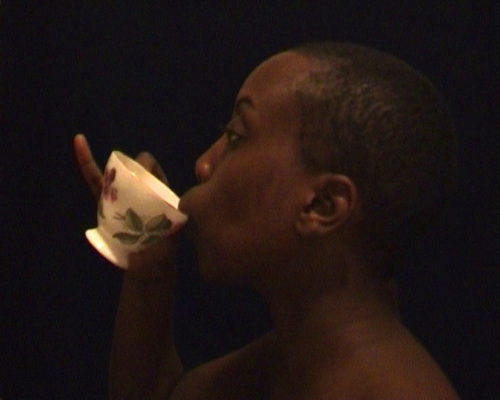

Grace Ndiritu, To Africanize is to Civilize, 2003 (Courtesy of the artist/Galerie Baudoin Lebon)

The latest issue of Savvy Journal (#3) includes an article, 'Transcending "Africa"', by Emeka Okerere, photographer and founder of the 'Invisible Borders Trans-African Photographic Initiative' (whose work we've been excited about here). It is an interesting contribution to debates about the recent successes of African art in the contemporary art world, which has been getting increasingly lively. In its first issue, Savvy published an essay — 'Where is Africa in the Global Contemporary Art?' — by Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, a Nigerian academic based at the University of California. Ogbechie wrote a forceful and rigorous piece on the misrepresentation of Africa in the international art community, where the continent is substituted for its diaspora. Even more striking and bold has been an article by Rikki Wemega-Kwawu–an internationally-renowned painter who works in Takoradi, Western Ghana–who has the the same questions as Ogbechie, but in harsher language: 'How could the "gutted whore-house" of yesterday overnight become the golden theater for the playing out of contemporary African art?'

Published over at African Colours in January this year, Wemega-Kwawu's essay — 'The Politics of Exclusion' — rages against the privileging of diaspora artists over those working in the continent. The essay forms the sixth part of the Stedelijk Museum's 1975 Project, which explores the relation of contemporary art to colonialism. Wemega-Kwawu's essay claims the recent success of contemporary African art as "deceptively positive, but ultimately degenerate". Wemega-Kwawu takes aim at a Western "coterie" in control of the international reputation of African contemporary art. Nigerian curator and critic Okwui Enwezor — Art Review's 42nd most important person in the international art community — comes under heavy fire.

I am proud I was one of the first to hail Okwui Enwezor as far back as 2003, when few people knew him on the African continent. … But he is beginning to go crooked. And I am only being a voice of the worried observers, the voiceless masses.

A central point of the essay is a point of familiar tension between the diaspora and homeland: the accusation that the so-called exile is in fact an economic migrant:

For one man's selfishness to justify his continual stay in the West, to protect a hard-earned empire with himself as Curator-Supremo, a whole continent's art must be marginalized and subjugated through self-satisfying, idiosyncratic strategies. This is preposterous!

Wemega-Kwawu may have valid criticisms about the art industry, but his personal speculations about Enwezor and lack of evidence presents the reader with grounds for some skepticism:

Something in Enwezor has changed. Something has softened. […] He once offered piquant, scorching critiques in a very belligerent manner. In 1996, he said of Jean Pigozzi and his collection in the africa '95 exhibition, that Pigozzi uses his money and connections to "legitimize and valorize many questionable artists (in his collection), pushing them to the world as the only 'authentic' artists from Africa".

Wemega-Kwuwa notices that — even then — the artists Enwezor proposed (Bili Bidjocka, Ike Ude, Yinka Shonibare, Olu Oguibe, Folake Shoga, Kendell Geers, António Ole, Oledele Bangboye, Lubaina Himid, and Ouattara) were all based in the West. Enwezor's sympathies move in the direction of a diaspora struggling to gain acknowledgment of the art establishment, but not for those who never left or, like Wemega-Kwawu, decided to return,

Enwezor's declaration that "Africa is nowhere, Africa is everywhere" is a particularly hateful soundbite [though it would be useful to know where and when he said it], and Wemega-Kwawu's argues that this kind of abstraction "should be challenged to the hilt". according to Wemega-Kwawu.

The strongest — and most concrete — evidence for the politics of exclusion is the difficulty for artists with African passports to get visas to travel. El Anatsui's Visa Queue (1992) crowns this argument. Last year the Guardian noticed that the UK visa system still excludes foreign artists. This has meant African artists have been less able to travel, and become internationally known, leaving them to become neglected by the international community, or await discovery by marauding international curators, who will never have sufficient knowledge of local communities:

A survey book on contemporary African art written today will be outdated in three years, at most. The creative energy of the African continent is simply overwhelming and has not been documented or theorized enough.

Wemega-Kwawu mentions an important survey — Nicole Guez's 1992 L'Art Africain Contemporain — which catalogs over two hundred Nigerian artists, only a tenth of whom lived in the West at that time. Nana Oforiatta-Ayim's 'Sketch for a Cultural Encyclopedia', currently in The Ungovernables at the New Museum, is a recent engagement with the difficulties of cataloging.

Wemega-Kwawu argues that assimilation of Enwezor — and others like him — into the homogenizing culture of international contemporary art means that a "golden opportunity to present African contemporary art as it truly was, as authentically reflected from the ground" has been "lost". If there is evidence to contradict this fatalism, it is the links being made between art institutions and curators and galleries in Africa.

Back to Okerere, who argues for a re-evaluation of African art according to a new understanding of trans-Africanism, which does not exclude or privilege the diaspora but takes the continent as a 'departure point' whilst calling for a 'rejection of brain drain and blind integration as a dangerous disease but better still, embrace the schizophrenic nature of multi-experiences as an advantage in the human advancement.' Okerere argues that 'Invisible Borders' represents a new attempt to confront the politics of representation. He lists a number of other initiatives which 'echo' the aims of 'Invisible Borders':

Pan-African Circle of Artists (PACA) – Nigeria, Art Bakery – Cameroon, Art Moves Africa – Belgium, Mobility Hub Africa – Belgium, Creative Africa Network, Appartement 22 – Morocco, Doual-Art – Cameron, Centre for Contemporary Arts – Lagos, The Addis Foto Festival – Addis Ababa as well as artist-led projects such as "Do We Need Cola Cola to Dance?" [below] by dancer and choreographer Qudus Okikeku.

To add to Okerere's list, writing from London, the first example that springs to mind is Tiwani Contemporary's partnership with CCA Lagos, and the first two group shows at that gallery, which staged conversations between the works of diaspora artists and those living on the continent. Or the Serpentine Gallery's On Edgeware Road project, partnered with the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo. This project, which brings London's Arabic community into dialogue with neighborhoods in Cairo and Beirut. The project celebrated its third birthday last month, and William Wells spoke about the cautious dedication needed to make such relationships real and reciprocal. Art should never be a golden theater. The representation of an Africa "authentically reflected from the ground", which Wemega-Kwawu so passionately describes, is not yet a missed opportunity.

* A critique by Ogbechie of Enwezor's practice was published by Aachronym in 2010.

Golden Theater or Gutted Whore-house?

Grace Ndiritu, To Africanize is to Civilize, 2003 (Courtesy of the artist/Galerie Baudoin Lebon)

Savvy Journal #3 includes 'Transcending "Africa"', an article by Emeka Okerere, photographer and founder of the 'Invisible Borders Trans-African Photographic Initiative' (whose work we've been excited about here). It is an interesting contribution to debates about the recent successes of African art in the contemporary art world, which has been getting increasingly lively. Savvy #1 published an essay — 'Where is Africa in the Global Contemporary Art?' — by Sylvester Okwunodu Ogbechie, a Nigerian academic based at the University of California. Ogbechie writes a forceful and rigorous piece on the misrepresentation of Africa in the international art community, where the continent is substituted for its diaspora. A more personal intervention was made by Rikki Wemega-Kwawu, who echoes Ogbechie in asking '[h]ow could the "gutted whore-house" of yesterday overnight become the golden theater for the playing out of contemporary African art?'

Published over at African Colours in January, Wemega-Kwawu's essay — 'The Politics of Exclusion' — rages against the privileging of diaspora artists over those working in the continent in international discourses of African art. The essay forms the sixth part of the Stedelijk Museum's 1975 Project, which explores the relation of contemporary art to colonialism. Wemega-Kwawu's essay claims the recent success of contemporary African art as "deceptively positive, but ultimately degenerate". Wemega-Kwawu, an internationally-renowned painter who works in Takoradi, Western Ghana, takes aim at a Western "coterie" in control of the international reputation of African contemporary art. Nigerian curator and critic Okwui Enwezor — Art Review's 42nd most important person in the international art community — comes under heavy fire. (A critique by Ogbechie of Enwezor's practice was also published by Aachronym in 2010.)

I am proud I was one of the first to hail Okwui Enwezor as far back as 2003, when few people knew him on the African continent. … But he is beginning to go crooked. And I am only being a voice of the worried observers, the voiceless masses.

A central point of the essay is a point of familiar tension between the diaspora and homeland: the accusation that the so-called exile is in fact an economic migrant:

For one man's selfishness to justify his continual stay in the West, to protect a hard-earned empire with himself as Curator-Supremo, a whole continent's art must be marginalized and subjugated through self-satisfying, idiosyncratic strategies. This is preposterous!

Wemega-Kwawu's description of Enwezor forms a compelling portrait, though the more personal speculations and lack of evidence presents the reader with grounds for some skepticism:

Something in Enwezor has changed. Something has softened. […] He once offered piquant, scorching critiques in a very belligerent manner. In 1996, he said of Jean Pigozzi and his collection in the africa '95 exhibition, that Pigozzi uses his money and connections to "legitimize and valorize many questionable artists (in his collection), pushing them to the world as the only 'authentic' artists from Africa".

Wemega-Kwuwa notices that — even then — the artists Enwezor proposed (Bili Bidjocka, Ike Ude, Yinka Shonibare, Olu Oguibe, Folake Shoga, Kendell Geers, António Ole, Oledele Bangboye, Lubaina Himid, and Ouattara) are all based in the West. Enwezor's sympathies move in the direction of a diaspora struggling to gain acknowledgment of the art establishment, but not for those who never left or, like Wemega-Kwawu, decided to return.

Enwezor's declaration that "Africa is nowhere, Africa is everywhere" is a particularly hateful soundbite [though it would be useful to know where and when he said it], and Wemega-Kwawu's argues that this kind of abstraction "should be challenged to the hilt".

The strongest — and most concrete — evidence for the politics of exclusion is the difficulty for artists with African passports to get visas to travel. El Anatsui's Visa Queue (1992) crowns this argument. Last year the Guardian noticed that the UK visa system still excludes foreign artists. This has meant African artists have been less able to travel, and become internationally known, leaving them to become neglected by the international community, or await discovery by marauding international curators, who will never have sufficient knowledge of local communities:

A survey book on contemporary African art written today will be outdated in three years, at most. The creative energy of the African continent is simply overwhelming and has not been documented or theorized enough.

Wemega-Kwawu mentions an important survey — Nicole Guez's 1992 L'Art Africain Contemporain — which catalogs over two hundred Nigerian artists, only a tenth of whom lived in the West at that time. Nana Oforiatta-Ayim's 'Sketch for a Cultural Encyclopedia', currently in The Ungovernables at the New Museum, is a recent engagement with the difficulties of cataloging.

Wemega-Kwawu argues that assimilation of Enwezor — and others like him — into the homogenizing culture of international contemporary art means that a "golden opportunity to present African contemporary art as it truly was, as authentically reflected from the ground" has been "lost". If there is evidence to contradict this fatalism, it is the links being made between art institutions and curators and galleries in Africa.

Back to Okerere, who argues for a reevaluation of African art according to a new understanding of trans-Africanism, which does not exclude or privilege the diaspora but takes the continent as a 'departure point' whilst calling for a 'rejection of brain drain and blind integration as a dangerous disease but better still, embrace the schizophrenic nature of multi-experiences as an advantage in the human advancement.' Okerere argues that 'Invisible Borders' represents a new attempt to confront the politics of representation. He lists a number of other initiatives which 'echo' the aims of 'Invisible Borders':

Pan-African Circle of Artists (PACA) – Nigeria, Art Bakery – Cameroon, Art Moves Africa – Belgium, Mobility Hub Africa – Belgium, Creative Africa Network, Appartement 22 – Morocco, Doual-Art – Cameron, Centre for Contemporary Arts – Lagos, The Addis Foto Festival – Addis Ababa as well as artist-led projects such as "Do We Need Cola Cola to Dance?" [below] by dancer and choreographer Qudus Okikeku.

To add to Okerere's list, writing from London, the first example that springs to mind is Tiwani Contemporary's partnership with CCA Lagos, and the first two group shows at that gallery, which staged conversations between the works of diaspora artists and those living on the continent. Or the Serpentine Gallery's On Edgeware Road project, partnered with the Townhouse Gallery in Cairo. This project, which brings London's Arabic community into dialogue with neighborhoods in Cairo and Beirut. The project celebrated its third birthday last month, and William Wells spoke about the cautious dedication necessary to make such relationships real and reciprocal. Art should never be a golden theater. The representation of an Africa "authentically reflected from the ground", which Wemega-Kwawu so passionately describes, is not yet a missed opportunity.

Independence Day in Namibia

Not only is it Human Rights Day in South Africa today (read up on its meaning by searching our archive for 'Sharpeville'), this day 22 years ago also saw Namibia wrestle itself officially free from the same Apartheid claws that were responsible for the massacre in Sharpeville. Which makes it a day both to remember and to celebrate. I'm picking up the Independence Day meme of popular music we started last year. 5 Namibian tunes. First up, Overitje group Ondarata's 'Tuvare Tuakapanda':

Patrick, Deon and Kamutonyo (aka PDK) mix Portuguese, Oshiwambo, Kwangali and Umbundu in 'Moko':

The prolific Tate Buti with Kamati Nangolo:

A bit older: Exit's 'Molokasi':

And Gazza's love song to Seelima:

You can dance to it.

March 20, 2012

Fabrice Muamba and English football

British football isn't known for its compassion, and it's already been an explosive season of racist slurs and handshakes denied. But the recent collapse of Fabrice Muamba, a midfielder for Bolton Wanderers, has shown a different side to both the professional football world, and its supporters, hoping for the recovery of a young player that everyone agrees is 'a genuine, warm boy'.

His collapse on Saturday at Tottenham Hotspur's stadium at White Hart Lane shocked the millions watching. As Daniel Taylor describes in The Guardian;

there is something deeply chilling when a young, apparently fit, professional footballer can suddenly be face down on the turf, and it is very apparent, just from the speed at which people are moving around him, the urgency of their body language and the way the other players are reacting, crying, praying, barely able to watch, that this is absolutely terrible'.

Tottenham Hotspur player Rafael van der Vaart, who was playing when Muamba collapsed, described it as 'the absolute low point of my football career', and other prominent players — Rooney, Barton and Defoe — have been showing their support on Twitter, using the hashtag #Pray4Muamba. Meanwhile, in Spain, Real Madrid players wore football shirts with 'Get Well Soon Muamba' stitched onto their chests.

Muamba's entry into Britain, and football, came after a tormented childhood in Kinshasa, and this outpouring of love shown in recent days offers warming proof of the power of sport to transcend prejudices and the racism that plagues the game, that otherwise challenge the political buzzword of 'multicultural Britain'. Racism has always been present in football, from the Suarez/Evra row, Terry/Ferdinand, or Atkinson/Desailly in 2004, and the 2007 investigation into anti-semitic chants by West Ham supporters toward Spurs players, football's double-edged sword are the fantastic foreign players it attracts, and the prejudice and racism they provoke in 'multicultural' Britain.

Yet, Muamba's cardiac arrest on the pitch on Saturday has offered some salve to the recent wounds that Suarez's and Terry's remarks have inflicted on football. Regardless of Muamba's immigrant or refugee status, he has been embraced as an excellent football player, with 33 caps for England at the Under-21 level. He's being celebrated as an ambitious young player, warm, generous, honest, humble; a rarity amongst the ever-richer, evermore egotistical footballing class of extraordinarily rich men.

Muamba was born in Kinshasa just before the first 1990s civil war there, and was forced to flee the country in 1999, when he moved to Walthamstow, East London, unable to speak a word of English and half-frozen by the alien English winter. His father, Marcel, had worked for Mobutu's government, and was threatened by the anti-Mobutu rebels who had formed the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Zaire (AFDL). For Muamba, as for many children in dangerous parts of the world, football was a means of distraction, of fun.

In an interview with Simon Bird, Muamba says:

"It was very difficult. It's been a long journey. Some people look at footballers and think it is about the cars and lifestyle, but don't understand how it was for some of us who changed life from Africa."

His words are a testament to how football's diverse players can be welcomed and nurtured. Muamba says, "This is my adopted country…People have helped me, welcomed me with open arms and given me this opportunity. I'm earning a more than decent living and leading a comfortable life. I'm very appreciative of that." (You can read the full interview here.) There's an element of pride in the recent shows of support, that Muamba is a well-liked, good player, saved from the situation in Congo by his new home, football, and England. It's something to be celebrated. It's just a shame that a player had to suffer from a heart attack to provoke such feelings.

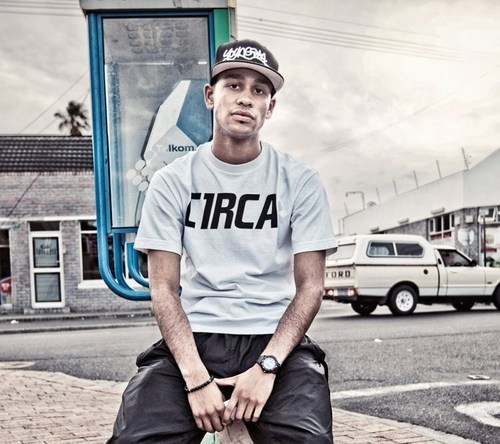

Cape Town African Swag

The first time I heard about rapper Youngsta (government name Riyadh Roberts) was during Public Enemy's tour of Cape Town, in a club awkwardly named @mospheer. Chuck D and Flavor Flav rocked the crowd that night, with a high-energy performance lasting longer than two hours (according to Flavor Flav's giant clock necklace). In the middle of their set they invited a few local MCs to get on stage and drop a couple of verses. A lanky and charismatic young man with a big grin, introducing himself as Youngsta, stole the show. His warm engagement with the crowd and funny, witty freestyles made him the clear favorite. This guy was going places. The next time I heard of him he was opening for Lil' Wayne.

Youngsta claims very much to be doing what he calls "straight up Cape Town hip hop" and I have to admit I hadn't been this excited about a local MC for a long time. But then I checked out this music video, called "Baggy."

It's evident in the video that his style is imitation American. (Let's not even talk about the second rapper on the track.) I get the sense that he is doing this forced, derivative"swag" to appeal to a mainstream audience. Since he is trying to make a career out of his work, can one really blame him? This is what sells, right? I get the feeling that audiences have developed somewhat though (even mainstream). I don't think sounding American is quite enough to cut it. I also think he is a lot more talented and relevant than he is showing us here.

Some of his work taps into "coloured" cultural politics, such as doing an interview and photo shoot over a Gatsby (a working class Cape Town version of a sub sandwich), and he has a clever, infectious homage to Cape Town, "Salute Ya" (a popular Cape Flats greeting) sampling Afrobeat and giving a shout-out to Cape Town hip hop legend Mr Devious. In his artist biography he blends his brand of self assuredness, with some sense of Afro-centricity: "It seemed as if no one was willing to step up and put the city on the map among the others in Africa — until now." His Facebook page suggests he is quite embedded in Cape Town's hip hop scene.

(It would be interesting to see what a veteran Cape Town rapper like Emile of Black Noise — in this video getting a group of coloured school children to at least recognize that they're African — would make of Youngsta.)

Youngsta prides himself on being somewhat of a mixtape king, having released 22 mixtapes in two years, and he has just released an album, Guyfox. He seems to have a restless energy in him, which makes him all the more interesting to watch. While his talent and output is prolific, I only hope he decides to focus less on the amount of work he puts out, and more on putting out good work. But less swag please.

'Banana republic'

World Soccer magazine explains Russian football's anti-racism strategies:

Anzhi Makhachkala have expressed their disappointment over an "idiotic" banana throwing incident involving recent signing Christopher Samba. The Congolese defender had a banana thrown at him from the stands after Sunday's defeat to Lokomotiv in Moscow. Samba picked up the banana and threw it back. "I hope this incident will become a example of how not to behave for those children who saw it at the arena," he said afterwards. Lokomotiv president, Olga Smorodskaya, a former graduate of the 'See No Evil, Hear No Evil, Speak No Evil' school of public relations, pleaded ignorance of the incident. "There were no incidents at the stadium on Sunday," Lokomotiv president Olga Smorodskaya said. "I was watching our fans during the match with great attention. They conducted themselves exemplary during and after the match." Russian Premier League spokesman Sergei Alekseyev said the league would do whatever possible to "change the situation" with regard to the country's appalling record of racism, but that legal action was not always possible. "The stadium in itself is a democratic environment," he said. "The police can seize flares, but how can they seize fruit?" he asked.

March 19, 2012

Undocumented Spanish News

Border fence between Spain and Morocco, Melilla (@ Nick Hannes)

Only three months have passed since the triumph of the conservative government in Spain. The economic crisis and labor reform have been key themes in the national and international press, with headlines about debt, the climbing unemployment rate (the highest in Europe) and the charges of corruption levied against businessmen and members of the government. Immigration policy, in the meantime, has been forgotten. Far behind us are the days when we would wake up to reports of undocumented immigrants jumping the barriers cordoning off Morocco from Ceuta and Melilla — two of the most heavily trafficked crossing points between Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa — or of makeshift boats washing up on the coast of Andalucía or the beaches of the Canary Islands.

Last week, Periodismohumano broke the news of the fifty-four men and women deported from Madrid to the Democratic Republic of Congo. After three years of struggle, hunger strikes, and protests, forty-three men and women were transferred from the CETI (a temporary processing center for immigrants) in Melilla to the CIE (the immigrants' detention center) in Algeciras and finally to Aluche, the CEI in Madrid. It sounds like a dream come true: arrival on the Peninsula, with the hope of living freely in a country whose regulations prohibit random deportation to their country of origin. Their companions from the CETI in Melilla were therefore shocked to receive a call stating that these men and women, as well as eleven already interned in Madrid, had been carted to Barajas airport in handcuffs, where five of them were beaten for refusing to enter the airplane that would leave them, hours later, at the dreaded Kinshasa Penitentiary and Reeducation center, recognized as one of the region's most dreadful hellholes. (More information on the case can be found in Blasco de Avellaneda's article in the Melillan daily El Telegrama.)

This is the most flagrant stain on Spain's immigration policy since the murder of several people who tried to jump the fence between Melilla and Morocco in 2005. Less than a week after the March 4 protest in Madrid held by SOS Racismo and other organizations advocating for the closure of Spain's immigrant detention centers, Rajoy's government has begun taking concrete measures against the country's immigrants. For years, the opaque CEI's have been cited by numerous national and international groups as well as by the country's official ombudsman for mistreatment of inmates, infringement of liberty and unsanitary conditions. After the deaths last Christmas of the Congolese immigrant Samba Martine in Aluche and of the Guinean Ibrahim Cissé in the CIE in Barcelona, Spain has become a lightning rod for the debate on the status of immigrants arriving from Europe's southern borders.

Such international papers of record as El País, La Vanguardia, and ABC have made no mention of the recent news, and Publico.es, an entity at least nominally freer from political obligations than the aforementioned three, seems to have cleared its conscience 24 hours later with the article "Raping Women: A Weapon of War in the Shadows of the Congo." On the other hand, it is only natural that room should be found for stories about members of the Guardia Civil rescuing pregnant immigrants, the first wedding to take place in Spain between two undocumented refugees, and denunciations of the human rights abuses taking place outside Europe's borders.

* This is a first contribution by Beatriz Leal Riesco in a series on Spanish coverage of African affairs. Beatriz is a PhD candidate at the University of Salamanca. She has lectured widely on Middle Eastern, and African cinema, and she serves on the selection committee for the 2012 New York African Film Festival. She has published in numerous academic journals as well as online at BUALA, Rebelión, Okayafrica and Africaneando. She blogs at Africaencine.

'South African History !X'

Fresh off a Japanese tour, Capetonian jazz musician Kyle Shepherd returns with a third album entitled 'South African History !X,' which, he explains in the video above, "pays homage to the languages of the first nation people" and brings to the front's South Africa's slave holding past. Featuring an all star cast of Jono Sweetman on drums, Shane Cooper on bass, Buddy Wells on sax and the late South African jazz legend Zim Nqawana, this looks like it's going to be a great listen.

The album teaser was made by the team behind the popular film Mama Goema: The Cape Town Beat in Five Movements (also featuring Kyle) which is now showing at the Cape Winelands Film Festival. If you're in Cape Town, go check it out.

The Branson Biennale for Morocco

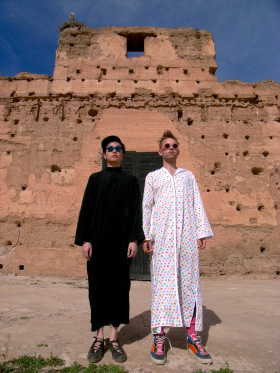

Vanessa Branson stands, hands on hips, her loosely hanging skirt tails give her the figure of a Western women making modest concessions to the predictable inquisitive gaze of an Arabic polis. Her trainers are burnished gold — a playful note — and what you wouldn't be forgiven for calling "ethnic jewelry" is slung around her neck. She has just organized the 4th Marrakech Biennale and looks proud of this achievement. Next to her, one of the young curators, Carson Chan, is dressed entirely in black, wearing statement glasses, with folded arms submitting mournfully to the publicity shot, any visible reluctance counterbalanced by a quiet confidence. It's quite clear who has the money, and who already suspects he knows how this image will be read.

Jamaa, a group of Moroccan and international artists who aim to make an intervention 'for' the biennale (but not necessarily 'in' it) have posted an excerpt of an email from Chan, who realizes that this photograph "encapsulates the many problematics of the biennale". On the wall behind the two are posters which, Chan says, the interns assumed were 'advertisement by the theatre royal'. This is a nice irony: they are in fact works from the exhibition itself. This raises an important question: who does this art speak to? The (local) participants who 'misread' this work of art as publicity? Or the photographer of this shot, who chose to shoot his subjects against this background to give it, as Chan ruefully identifies, an '"exotic" look?

There have been internet rumblings around the biennale — called Surrender — which opened two weeks ago. The centerpiece is an exhibition — Higher Atlas — which runs until May. We noted some potential problems for the project just after it opened: the program looked self-defeating: an odd selection of Western artists, too few Moroccans, and one Cameroonian. Looking at the festival's brief history the determining factors for these priorities and exclusions become clearer.

Established in 2005 by Branson — entrepreneur and sister of Richard, Britain's cheekiest billionaire — the festival publicity boasts it is the first trilingual festival in North Africa. Branson lives in London's exclusive Notting Hill, but travels often to Marrakech, where she owns a boutique hotel.

In this interview, Branson admits that she still is an 'outsider' in Morocco, but cheerily adds that it 'gives you a position where you can see everything coming and going'. This is a useful summary of the poor assumptions of this project: that the insights afforded to someone who travels to a city for pleasure, in publicity stunts with the super-rich, or to establish boutique hotels, can achieve anything more than brief and partial. Branson first travelled to the country during her brother's famed (?) attempts to traverse the world in a large publicity balloon. The Branson family business is, it seems, hot air.

The biennale was, she says, an attempt to single-handedly redress the 'social madness' which happened after 9/11: "I tried to replac[e] the balance a little bit by having the arts festival. I know that arts can be a wonderful platform to debate topics like identity, women's rights, freedom of speech. Free and creative thinking haven't been encouraged in islamic countries."

This biennale, it seems, is Vanessa Branson's answer for Morocco's — indeed the wider Arabic world's — problems.

Q: Does the discussion feel liberating?

A: Definitely. There is no tradition in criticism or in reading. The Koran was the only book that was read, the first decent literature was published in the late 60ies.

But who has been liberated by these discussions? Branson — or the country of Morocco? The country, she seems to be suggesting, is feeling the warm glow of Western liberal democracy, thanks, in some small part, to this occasional program of contemporary art, literature and film. Perhaps Branson feels liberated by the idea that she is bringing the very concept of criticism to virgin lands (no pun intended). Who could have foreseen that Moroccan modernity would receive such a heroic transformation at the hands of a Western woman? Coverage of previous biennales has been similarly ridiculous, including this New York Times piece, entitled 'Boldly Bringing Art to Old Morocco'.

The transformation of Marrakech which the biennale apparently fostered, has made the city into a 'creative hub'. This means Moroccan artists don't 'go and live in Paris and New York'. Such goals are surely positive, as the ongoing debate into African contemporary art and its diaspora constantly iterates. The organizers say real exchanges that take place at the festival are made possible through the biennale's relationship with the local university, whose students intern to help with the administration and whose families give resident artists authentic contact with local people.

Branson explains the thinking behind this year's title:

Q: What says the 2012 title Surrender for you?

A: We chose this title for [its ambiguity]. It shows the world how open minded Marrakech is as a city. To the Arab speaker Surrender means Open your mind. Surrender your self to new ideas and doesn't necessarily have a religious connotation.

The promises Branson makes for the impact of her festival are determinedly secular. As if religion should play a part in such 'cultural' conversations. As if Islam doesn't represent an extraordinarily diverse and sophisticated critical and literary culture. If Branson celebrates the biennale's stance 'at odds with the world perception of anti Islamic feeling', it is because her Morocco is not Islamic.

The imperative — Surrender — stands alone. This is contemporary art's entreaty to the citizens of Marrakech: surrender your critical judgments, your religious views, your cultural background, the narrow confines of your epistemic system, shed the habiliments of your lives at the door; enter and let International Contemporary Art give you its thoughts. Resistance is futile!

Next, consider Carson Chan and Nadim Sammam, the two young curators of the Biennale's Main Visual Arts Exhibition. Both have impressive CVs which detail extensive work in European and American contemporary art, reproduced in most of the articles on the festival. Consider their impressive eye-wear, both avant-garde and practical!

Chan is ying to Samman's yang. Chan's plain black robe and basic sandals represent a monkish devotion to the aesthetic. Samman wears a garment spotted with Damien Hirst's trademark which makes him look like an outpatient at a ward for victims of post-modernity. His retro trainers, left diffidently untied, smack of a Western Weltschmertz. The building they stand in front of represents Morocco: bare and authentic, a wall for their art. The way perspective works means they are almost as tall as the building, their excessively large bodies obscure the door.

This interview with Carson Chan is instructive. It smacks of the good intentions and political sensitivities behind the whole project. It turns out Vanessa met him at Art Basel in Miami, where he impressed her with an iPad presentation of his past exhibitions. She had met Nadim at an exhibition in London the previous month. Chan's reaction to his experiences in Marrakech mainly involve pleasurable surprise at the (presumably correct) responses by 'visitors that have had very little exposure to contemporary art'.

Q: Did the "arab spring" affect you curating this project?

A: The so-called Arab Spring (no one here would ever associate any kind of political unrest as a problem relating to other countries…) was definitely on my mind when I started conceptualizing the exhibition. Before spending time at in Marrakech, all I knew of Morocco was what I read about in the media — a politics biased reading if anything. The very fact that we made an exhibition of contemporary culture was a response to politic-heavy understanding of North Africa.

At Africa is a Country, we approve of skepticism to do with the 'Arab Spring' designation, but here it is misapplied. The suggestion that political unrest is unrelated to similar struggles in neighboring countries is obviously ludicrous. If anything the 'Arab Spring' proved that repressed elements in society are capable of identification beyond national borders. Not 'we want what they have' but 'we want what they want'. Equally ludicrous are the claims to representativeness Carson makes: 'no one here would ever …' But this is an exhibition, as he reminds us, which was 'curated to appeal first and foremost to the senses'. We all have them, right? But can we say with any confidence that the senses transcend political determination? Just as Branson claims to sense Marrakech being liberated by her festival, these curators seem to think they have constructed a new sensual geography. Carson's intuition that Morocco's representation in the Western media is politically determined is fine, but the suggestion that these two curators could somehow achieve a radically different cartography of Morocco's position in the contemporary world picture is absurd. Lastly, his measurement of normality ('[p]eople here' are 'just like everywhere else') is worrying: Carson's discovery that '[p]eople here' are 'just like everywhere else' is founded on the fact that many Moroccans he has come across are active participants in global capitalism, identification through shopping or using the internet.

The interview ends on an odd note: Chan notes that the 'exhibition vernissage' was for him the most stimulating part of the whole project. Is it cruel to suggest that this is telling — that the curator's favorite moment happened before the public entered?

In response to an invitation to participate in the biennale, Jamaa formulated an intervention which manifests itself as a 'Proposal. Statement. Interview. Conversation.' (You can read it here.) It makes a series of implicit criticisms of the theoretical grounding of the biennale. Quoting from Chan's essay in the exhibition's bilingual (English and French) catalogue it seems the organizers are trying to be sensitive to the political problems they face. Chan seems blithely positive about the impact of such events, which "not only bring with them a diversification of how art is defined and culture disseminated, but the financial incentives from cultural tourism (i.e. increased hotel, restaurant, retail, and transportation revenue) and the suggestion of societal maturity [which will] have a visceral effect on the local economy and culture". Post-colonial questions into the politics of this 'maturity' is, Chan believes, "like beating an old horse".

If this reading has appeared gratuitously aggressive, it is because there simply has not been careful enough thinking into the politics of local and global, of how international contemporary art maps out the countries which it claims to be constituted by. This event could have staged conversations with the rest of the world which originated from within the community itself. Branson's money could have been spent on a project which actually engaged the local culture, bringing it into a new conversation with an international community. For Chan, this exhibition took place in a country "like any other", for an audience that isn't "uniquely different". These statements refuse to acknowledge that an exhibition of contemporary art always constitutes a gesture determined by the culture in which it is staged. The lack of thought about what this culture might be is unforgivable. The organizers don't seem to really care. We must remember, after all, that we have been told to surrender ourselves.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers