Paul David Adkin's Blog, page 32

August 3, 2016

The Tragedy of Authentic Christianity

The saddest thing about the story of Christ, is not the horrific suffering of the Crucifixion, but the utter destruction of Christ’s teachings by Roman civilisation.

There is a fundamental question which needs to be asked by any Christian: If Christ taught the Truth, why did those teachings need to be ‘civilised’?

The saddest thing is that, if Christianity had triumphed over Roman Civilisation in an authentically Christian way, instead of being absorbed by it, there would have emerged a far more human historical process than the anti-human historical process we are suffering the consequences of now. A triumphant Authentic Christianity would have been a triumph of pacifism, seeing the end of wars – and such an achievement would also have meant a triumph of human will. Christ would have truly been the Ecce Homo, the First Man after the authentic revolution towards a truly human global society based on true respect of other human beings.

Society would have been community orientated, without the divisions of segregating identities; without our family-centrism; without tribes or nationalities. It would be a society that would abolish money and would have developed a more holistic and purposeful system for developing incentives for creativity.

Christ was not a dogmatist, otherwise he would have written his dogma down. When Roman Civilisation made Christianity its own creed, it knew this and with a total cynicism for the Truth it was expropriating for itself, it created its own Roman Christianity that became the civilising model for all other civilising Christianities. In the process perverting the great revolutionary spirit of the Word and turning it into something profoundly conservative.

August 1, 2016

ON NEUROSIS

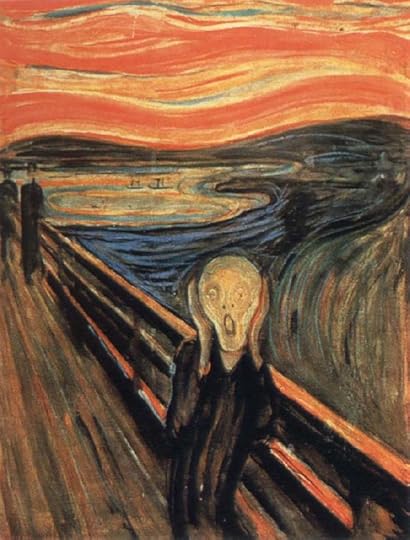

For the neurotic, reality is an intrusion. The neurotic is the one who says: “Life is awful; it is so full of reality.” There is a paradox here: Is the neurotic disturbed because of his or her rejection of reality, or is reality itself something that actually makes life awful, and, therefore, creates the neurotic who finds it intrusive? The neurotic lives an illusion: but that illusion is that things should be better.

From a moral perspective, the neurotic is right – things should be better. But, if this is the case, why can’t we learn from the neurotic? If we listen to the one who thinks things should be better, we might be able to see how better things can actually come about. Instead we nullify the neurotic mind, tranquilising its Utopian-born anxieties with drugs. Civilisation tells us that neurosis is a terrible illness, not a path to enlightenment.

But, how is neurosis an illness? According to Horney the neurotic’s problem is that he or she makes claims on things that they are not actually entitled to. The result is indignation.

It is here that we see how neurosis seeps into the very fabric of society; through the fantasy of entitlement, which is itself created by the ambiguity of that same entitlement that is fostered by civilisation. How far do our rights go? How extensive are our entitlements? What does our democratic freedom provide us with? Once one starts to attempt to answer these questions, one is pushing oneself ever closer toward a neurosis.

But inspiration itself is a neurosis forming phenomenon. The illusionary reality of the neurotic is encouraged by the System itself: “You deserve that car that you can’t afford, and because you deserve it we will give you the finance for it – all you have to do is pay us back with interest.” The luxury car, in the neurosis creating system, becomes a neurotic need. Of course it isn’t an authentic necessity for anyone, but the system tells us that it is.

The neurotic is a passive creature, “all the good things in life, including contentment of soul, should come to him,” and the neurosis creating society must also fabricate passivity. A passivity which is linked through neurosis with consumerism.

K. Horney, NEUROSIS AND HUMAN GROWTH, p. 40

Ibid, p. 41

July 30, 2016

Information (2): Vs Religion

In our previous entry (Information 1), we proposed the idea that information is a metaphysical concept that bridges the divide between the material and the spiritual. We argued that information is omnipresent and that it is part of the subatomic fabric of the Universe. Subsequently, information is in everything and that everything is basically information; and, because the end result of information is ‘knowing’, this also makes information (in its complete form as the Universe) omniscient.

Of course, this is all sounds like a description of God, so perhaps we could create a new religion from it … A religion? Another religion? Oh, please, God forbid!

No, we don’t want another religion; but perhaps if we consider information as God and try, in a post-Leibnizian way, to imagine what an Information-worshipping religion might be like, then we may also get an insight into the way religions work as well.

So, if God was Information then how would the Church of Information be different to other religions:

FIRSTLY: There would be an absence of the mysteries that other religions are shrouded in. There is nothing mysterious about Information. The religion would operate without any occult pretensions; its followers would be awestruck and inspired by its magnitude and by its infinite possibilities in the same way that the arts and sciences can be awe-inspiring once one embraces them.

SECONDLY: Information in its pure form is not usually dogmatic, whilst religions are dogmatic. We have shown, in the previous post, that Information can be ethical because the uses we have for Information can be good or bad. Yet, while there is a kid of sin involved, if we use Information in a way that could be fatal to Information itself, there is no divine retribution.

THIRDLY: Information is not ceremonious: the celebration is inherent in the concept itself. Life as a conscious deciphering of information, is itself the celebration.

FOURTHLY: Religions are traditionally based on the idea that there is a better world beyond this one, and hence, this place and life is a mere transition to the other world. In an Information based religion there would be no Apocalypse or Final Judgement, no Paradise or Hell beyond this Universe. Leibniz was right in saying this is the most perfect of Universes, but not because it was created by God, but because it is the only Universe. There is Existence (through conscious, information deciphering entities that, through the objectifying consciousness of their collective subjectivities, allow existence itself to come about) or non-Existence. The final purpose of Information is to ensure that conscious, sapiens organisms can exist permanently in the Universe, and, by doing so, ensure the Permanence of the Universe itself as well. It is through the idea of idea of Permanence that a new optimism arises, that will bury the old nihilisms and point us in a positive direction with deep will for survival.

Without mysticism, dogma, ceremony, an Apocalyptic eschatology or any Heaven or Hell, our religion of Information can hardly be considered a religion at all. The real question that arises here is: Can a positive principle be expected to motivate large groups of people, and create positive revolution, without the vulgar trappings of mysticism, dogmas and promises of Paradise?

But, in order to answer that question, we need to examine the organisations that make religions work. We need to look at Ideology.

July 28, 2016

INFORMATION (Part 1)

Is information intellectual or physical; material or spiritual? The power of understanding information is certainly an intellectual one, but what is the essence of the information itself that our minds are deciphering? Information is a good reason for having a mind, but it doesn’t fully depend on the mind to be communicated and deciphered: there are other kinds of information – biological information, for example – that are unravelled and understood by all living organisms without any minds taking part in the mechanics of communication and deciphering at all.

If we consider the information shared by subatomic particles, which are the basis of everything, then we might be able affirm that information is everything and everything is information. We can certainly say that information is in everything and that everything carries information. And from this, we can see how information in fact transcends the spiritual/material divide; it makes the physical something omnipresent and God-like and turns the spiritual into a material thing that is part of the essence of the matter that makes up the universe. Information is the triumphant champion in the spiritual vs. material dialectic struggle: everything finds its unity in information.

Since in this light, the process of thinking turns into an almost holy ritual. It becomes a conscious celebration of the deciphering and communication of information. As conscious organisms, our human, homo sapiens, experience is therefore in constant homage to, and a celebration of, information. So, if we have to start a new Church, erect it on a rock of Information. We already have the word for it, so there’s no need to call it God, and we celebrate it every time we open our eyes or ears; every time we touch or taste something; each time we utter a word or statement; whenever we read anything or watch anything; or even each time we dream – our entire sensory, intellectual existence is a great celebration of Information.

THE ETHICS OF INFORMATION

At first glance, little else can be said; all conscious unravelling of information, good or bad, is involved in this great act of celebration. However, given the nature of celebrations and rituals, we must consider the fact that there can be a “good” and “bad” way of celebrating.

Let’s assume that the Good Celebration is that which is Consciously Deciphering Information. From this we can come to ethical conclusions and deduce that a Bad Celebration would be one which would be a threat to the Celebration of Information itself. Or, in other words, all thought, which is a conscious deciphering of information, is good, except when it threatens the destruction of the capability of thinking itself. Through its restrictions on creative thought, dogma is therefore an evil process. At a greater degree of evil lie the thoughts that would endanger the existence of conscious organisms by creating conditions that would threaten their existence. The destruction of sapiens life-forms, through environmental degradation of internecine conflicts, has to be regarded as bad. In fact, any thought processes that create the destruction of sentient beings (wilful or accidental) should be regarded as Absolute Evil.

If we assume that consciousness is most highly developed in humanity, any threat to humanity is evil. As humanity depends on the Earth’s atmosphere to survive, any threat to the Earth’s atmosphere is evil; etcetera.

Likewise, good is embodied in life-affirming ideas. Life allows deciphering; it allows consciousness; it is the first great imperative. Good can also be seen in attempts to reach new and deeper decipherings and in developing the potential inherent in Information through the sciences: both pure and applied. Always, of course, if those discoveries are not applied in a negative, “evil” way.

The mere awareness itself of taking part in the Celebration, should have an animating influence on the individual. Through this celebration we are placing ourselves back in the centre of the Universe, investing ourselves with the purposefulness of it and emphasising the importance of our permanence and, obviously, our survival.

July 3, 2016

Zombies, the Brexit and Dystopia

“…man is in the world, and only in the world does he know himself.”

Merleau-Ponty, PHENOMENOLOGY OF PERCEPTION, Preface, p. xii

Man is in the world … And if this is true for humanity, we need also to remind ourselves of it whenever we examine societies and our civilisation.

Civilisation is only realistic when it is perceived within the context of the world – or, in other words, within its ecological context.

Nevertheless, democracies largely ignore their relationship to the environment and give precedence, time and time again, to their own self-made fantasy-reality that it calls ‘the economy’.

Civilisation has always been a challenge to the natural world; an audacious move by human beings to harness nature for our own ends in order to create a mode of existence that is superior to nature itself. But what Civilisation has gained by developing beyond the in-the-world context, it has also had to sacrifice its authenticity. It has become a fantasy form of its own potentialities, manifested in the madness of the economic doctrine of perpetual growth.

For authenticity to be returned to civilisation, there needs to be a re-establishment of partnership with the world, rather than a continuation of conquests of land-spaces and a pillage of non-renewable resources.

We are driving a juggernaut along a road which leads directly to a cliff edge. If we go straight, we will topple into an abyss.

To avoid this, we have two choices: we can either turn left toward a Utopia, or right into a Dystopia.

Given this scenario, why is it so hard to decide which way to go?

Driving forward the way we are, will only bring about deeper and deeper systemic crises. Technological advancement has to create more automation and the digitalisation and robotisation of societies, combined with the continual increases in population density, can only further decimate jobs. Concentration of wealth and the centralisation of job opportunities to the growing megacities will continually draw desperate, poverty stricken outsiders to those centres.

The easiest solutions are the Dystopic ones: the erection of walls to keep the immigrant invaders out. Ties between capitalism and zombie invasion metaphors have been made over and over again by many bloggers and intellectuals like Slavoj Zizek.

In the Brexit, we’ve been able to witness how easily a society can be swayed toward a Dystopic solution. When the outside world is too frightening to face, then the safest thing to do, say the Dystopics, is to retreat and gather together in a fortress with walls that are strong enough to withstand the encroaching invasion.

The idea of the Brexit is to allow Britain – probably in a diminished form from what it is now – to do its business with the world in a safe position, removed from the very chaos that that ‘business’ has created and will continue to create.

Essentially, the Brexit is riddled by the paradox inherent in all Dystopic solutions. The Dystopian is terrified by our world, but, instead of trying to imagine that world as a better place, it continues throwing more fuel into the motor of the chaos that scares it so much. In a sense, we have the capitalist Doctor Frankenstein hiding himself from his plague of monsters, but it doesn’t mean he wants to eradicate the plague. Quite the contrary, his retreat is merely a tactical one, in order to observe his beasts from a safe place: behind the walls that are heavily guarded, and with special forces that will occasionally venture forth to stir up the chaos even more.

Utopic vision, on the other hand, embraces our world, and looks for ways of turning technological advances into a working alternative that offers an immensely better world – primarily much better because it promises a long-term survival for humanity in this world.

https://radicalscholarship.wordpress.com/2015/10/11/are-we-the-walking-dead/

http://revoluciontrespuntocero.com/the-walking-dead-y-la-ideologia-del-capital-post-industrial/

May 15, 2016

DADDY DEMOCRACY IS NOT THE FATHER WE THOUGHT HE WAS

alienation democracy – Bing images

There is a general feeling of alienation between the electorate and the political echelons in most of the so called democratic world, and it is important to remind ourselves that this alienation, which is real, is taking place precisely when our democracies have applauded the downfall of most of the world’s dictatorships. So, how can this be? If the world is more democratic than ever, how can it be that people are feeling alienated from the political system? The situation should be the opposite. Could it be that the accuser, now left with hardly anyone else to accuse, is now revealed for what he truly is and always was? That the accusations were smoke-screens in order to cover up his own guilt? Aren’t we now like the child who discovers indications that our perfect father is not so perfect after all: we don’t go out and openly discredit him, although deep down we would like to; we don’t run away or disown him, although we are tempted to; we start to rebel and stand up to his authority, but we don’t really believe we can change him … do we?

What we have now is quite a unique scenario. Perhaps for the first time in history, we find ourselves having to turn our backs on that which we never really had. We thought we were free, but it was a lie. So, what should we do? Try and recreate that which never was? Try and create in a real way that which we thought we had but never really did? But, how could we ever trust them again?

Once innocence is lost, it’s impossible to return there again.

April 21, 2016

THE PROBLEM OF MORTALITY

Of all human problems, ultimately, the greatest problem of all is our mortality. One day we will die. Add to this the ancient notion supported by modern physics that the Universe is headed toward an inevitable annihilation, and we find that humanity is subjected to and conditioned by a tremendous pessimism. Everything must come to an absolute end. Any will to permanence is an illusion. Vanity of vanities.

The more sensitive ones: the artists, the sensualists, the hedonists, call out Why? They all have a longing for permanence. “This is good and should not end,” is the optimistic attitude. And yet no-one, and nothing, can escape it.

From the dismay this causes come the religions who promise the eternity that reality denies us. The message of religion is essentially that the dictatorship of death can only be transcended through the faith in the idea of another reality – the authentic reality which is permanent.

But the faith does not change the material reality, in fact it needs its pessimistic inevitability to justify itself. However positive faith in the afterlife is, it ultimately creates a pessimism here on Earth. In fact, religious hope for the eternal in the transcendental creates a nihilistic attitude. It was a blind faith in the absolute afterlife, the Paradise of the monotheisms, that created nihilism, not the turning away from that faith.

Once the objective became to get to the Paradise, real reasons for living here on Earth were no longer important. The only thing that mattered was Absolution or Providence. The idea that humanity itself through a manipulation of the physics of reality, could prolong life expectations and control nature through understanding, were condemned as ideas that came from the Dark Side. A dark, magical side that eventually evolved into science, which offered enough illumination to return human faith to itself again.

Perhaps the most positive idea we can have at the moment is that there is no limit to what the magic of science could achieve. Perhaps eventually humanity could become immortal and even the dying Universe itself could be resuscitated by our most advanced science and technologies.

The authentic world is here, and we are tiny in it, although our minds enlarge us. But the positive idea can only be truly positive if it is seen as a possibility. The most likely future for humanity is the dystopian version and positive thinking and action have to be a contemplation of how to escape the Dystopia and arrive at the Utopia. Or to get away from the process of becoming Dystopia and more into the process of becoming Utopia.

April 17, 2016

Crash Course Philosophy #8 – Karl Popper, Science and Pseudoscience — Hop on a Comet

Only reluctantly do I admit that philosophy and science are neither mutually exclusive nor at war with one another. My reticence in this matter is due to my disdain for some of the obscurant language that often pervades philosophical work; so often it seems unnecessary and certainly unhelpful. And while I understand the need for […]

via Crash Course Philosophy #8 – Karl Popper, Science and Pseudoscience — Hop on a Comet

April 8, 2016

OUR THYMOTIC PATHOLOGY 2: Achilles, Odysseus and the Bicameral Mind

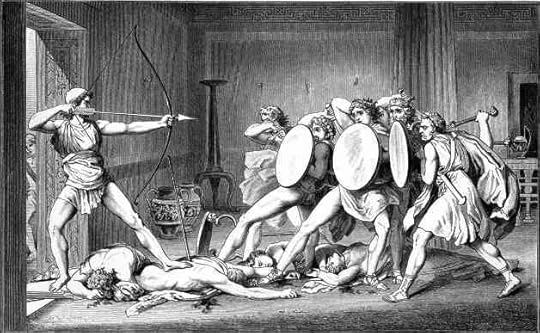

In the evolution of Greek culture from the menis (cholera/rage) of Achilles to the metis (astuteness) of Odysseus we see a new power emerging in our species – the power of consciousness; the power of the mind. It is Odysseus and not Achilles who vanquishes Troy.

If Jaynes’ analysis of Homer and thymus is correct and that an evolutionary leap took place between the composition of the Iliad and the Odyssey, showing us a literary expression of the transformation of the Bicameral unconscious man (Achilles) and the Conscious man (Odysseus), thymus and menis could also be regarded as biological facets of our temperament that were necessary to the unconscious man in his bicameral state, but became only a troublesome element for the conscious intelligence of our non-bicameral minds.

It is not the Achilles figure bursting with menis, or Hegel’s aristocrat hero sacrificing himself for his slave who should be posited as candidates for the title of the First Man, but rather the wily Odysseus. Odysseus is the first man, the first figure in world literature, who would be the first to display the tremendous advantage of consciousness and the astuteness that that consciousness empowered him with. Rather than a step forward, Fukuyama’s Hegelian idea of the triumph of thymus and the megathymotic instincts of liberal-democracy and capitalist society is in actual fact a backward leap in ontological evolution.

The Iliad man is slave to passions, which are not his passions but drives instilled by gods. It is Achilles’ thymus, stirred by Apollo, that makes him rise, leave his tent and go to battle. Achilles is a kind of schizophrenic automaton. He doesn’t think of himself but only acts when the gods tell him to act or when they stir his thymus. He is a patient potency that will explode when ignited. He will sit and wait, absorbing the world until he is called to act. He is an archetype for the invulnerable power of the masses. The masses who are stirred via their own thymus: the thymus of all religions and all nationalisms; loyal to all flags; the champion of all victims of any injustices. Achilles evolved into the masses and his thymus and his menis were preserved for anyone cunning enough to tap into to use.

Achilles, the archetypal hero of all who act when they are stirred, is a robot warrior. He is superseded in homo sapiens evolution by Odysseus, the genius survivor. As the archetypical automaton-man, Achilles is the first example of Nietzsche’s Last Man. The gods of Olympus are no longer the instigators and thymus stirring invisible protagonists of our current unfolding tragedy. They have been replaced by the cunning sons of Odysseus who learned the art of domesticating all Achilles-men. But now Achilles’ descendants, the Last Men, also have consciousness, or at least a latent consciousness, and the new god-king race of the Odysseus family must apply even more ingenious methods of manipulation to maintain the Achilles-masses automaton-slave condition.

The historical process has become a struggle to manipulate the Achilles-automatons, and keep them unconscious by convincing them that they are really free. But in between the Odysseus-god-kings and the Achilles-automaton-slave-masses are the other classes of men and women. Strange Odysseus-like creatures who use their intelligence not for cunning and manipulation but for knowing and teaching. They evolved in the post-Homeric times of poetry and philosophy (and Homer himself belonged to this same class). They stand on the outskirts of the prayer process of history, part of it, but never really accepted by it or accepting of it. They try to reshape it, redirect it.

If Jaynes is right, mankind as a consciously thinking species, as a true homo sapiens, has only existed for some four thousand years. Hegel saw life as a long process of becoming. A tedious but necessary process. We know that evolution has had its failures and there have been countless extinctions, so how should we imagine mankind in one or four thousand years’ time? If we were to meet such a person time-travelling back to our era we would probably not consider them human any more, just as we would probably have trouble relating in any meaningful way to Achilles. We are always in the middle of what we once were and will eventually become.

In the 1960s, when science-fiction writers tried to envisage an evolved humanity they gave us huge hands and long fingers. But our next great evolutionary leap will probably be like our last, not a physical change but a leap of consciousness. In the future men and women will have a more quantum awareness, perhaps with greater sensitivity to electromagnetic fields and, certainly, areas of the brain will be activated that we have never consciously used up to now. The shift from Jaynes’ bicameral Achilles to conscious Odysseus involved a shutting down of the bicameral activity and an activation of that part of the brain that makes us aware of the I.

We have evolved and we will evolve again if we survive extinction. “The goal is Spirit’s insight into what knowing is,” wrote Hegel. And for the Spirit to know through mankind then mankind’s perception will have to grow more acute and more finely tuned to nature. In the meantime, we must struggle against the bi-polarising of society into a conscious and unconscious one and the maintenance of that bi-polarised status quo. We still have a segregated society of Odysseus-royal-elites and Achilles-slave-masses, and a power struggle between the two. The automaton class tryies to preserve its dignity by demonstrating that it has clear consciousness, while the royal elite amplifies the servility of its multitude through the machinery of religions, patriotisms, publicity, spectator sports and other spectacular events for the masses.

Julian Jaynes, THE ORIGIN OF CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE BREAKDOWN OF THE BICAMERAL MIND, First Mariner Books, 2000

G. W. Hegel, PHENOMENOLOGY OF SPIRIT, p. 17

PART ONE:

OUR THYMOTIC PATHOLOGY – 1: Fukuyama and Sloterdijk

OUR THYMOTIC PATHOLOGY – 1: Fukuyama and Sloterdijk

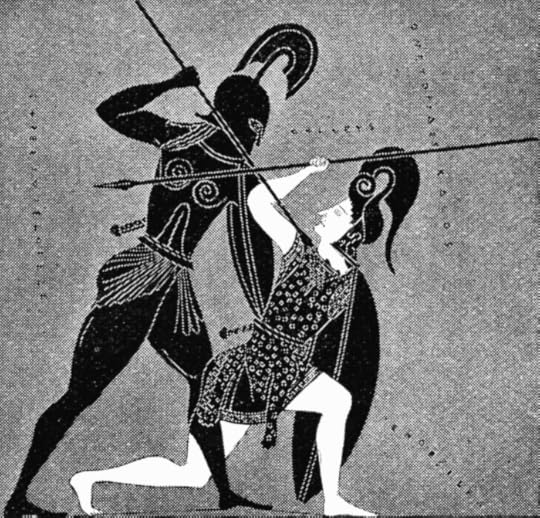

The ancient Greeks had a concept called thymus which, they believed, explained our unconscious impulses to act. In the Iliad, Achilles does not act consciously, but rather it is Apollo who inspires him to go to battle by stimulating his thymus.

Of course, as a subconscious driving force, thymus can be likened to will, or a physical, personal receiver and motivator of will. Julian Jaynes’, in his book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, argues that the meaning of the word evolved in its classical usage from an original concept of motion or agitation in the unconscious bicameral man, to eventually become something like our emotional soul. Perhaps in its original meaning we could sometimes associate it with energy – when a man grows tired of moving it is because his thymus leaves his limbs – but it must be given a spiritual or psychological quality as well which seems to come and go and even gives us directions. It speaks to us. The thymus can tell a man to eat and drink, or to fight. Diomedes in the Iliad says that Achilles will fight: “when the thymus in his chest tells him and a god rouses him.” Thymus then, is associated with passion.

Fukuyama introduces thymus to us through Plato. From the Republic, Fukuyama tells us that Plato envisaged the soul in three parts: desire, reason and thymus, which Fukuyama translates as spiritedness.

What Fukuyama is looking for constantly in his book is a handy definition of human nature. Definitions which can correspond to liberal-democratic intentions and thus prove Fukuyama’s thesis that liberal-democracy is the most perfect system because it reflects human nature far better than any other. Plato’s triumvirate-soul is perfect for Fukuyama and capitalism: a will to spirited desire that also has a sprinkle of reasonableness to it. Plato of course saw the triumvirate working in a different way. Its tri-nature being an explanation for the constant moral dilemma between our reasoning and our desires. Plato asks: shouldn’t we subject our desires to the judgement of reason against the danger of allowing it to be subjected to passion? Capitalism of course would argue NO. It’s better for the consumer to desire with a passion and consume with a frenzy. Capitalism wants a passionate element to reign in our souls. The kind of passion propounded by the Romantics, the kind advocated by Nietzsche.

To act with passion the consumer needs freedom, and so the liberal-plutocracy encourages it, or at least a hallucinatory version of that freedom. While you are allowed to consume with passion, you will be fully motivated to work in our system, the one, the only one that can provide the drugs one needs to feed one’s consumer-addiction – which is making the few who are pulling the strings get richer whilst the rest sink deeper and deeper into their addiction. Welcome to Huxley’s Brave New World.

For Fukuyama: “Desire and reason are together sufficient to explain the process of industrialisation and a large part of economic life more generally.” But what room is there for reason in a soul that is driven by a spirited, passionate desire? How much reason can we see in an industrialisation which has scarred the planet? How much reason behind those ideas that created a slave-class of factory workers that are now abandoned to unemployment as the system mechanises the same industries? Instead of the noble concept of reason, we see only egotistical ambition. Only selfish reasons based on greed and desire.

Fukuyama perverts Plato’s idea of the soul by associating it with a singularity that is human nature. Plato himself, however, does not make this association, and in the dialogue Socrates is searching for the best individual natures to fit certain positions (e.g. what would be the right soul for an ideal guardian of the city). Plato’s argument is that the appetitive part of the soul that is desire needs to be controlled, not unleashed as capitalism does.

Fukuyama seems quite liberal (no pun intended) with Plato’s thymus. In Republic IV, 436a ff., Socrates asks: “Do we do things with the same part of ourselves or do we do them with three different parts? Do we learn with one part, get angry with another, and with some third part desire the pleasures of food drink, sex, and the others that are closely akin to them? Or when we set out after something, do we act with the whole of our soul in each case?” Or in other words the three parts that Fukuyama refers to are: that with which we learn (reason), that which gets us angry (thymus), and that which fills us with desire. Here Fukuyama’s translation of thymus, spiritedness, would probably be better rendered as passion, for thymus here is the faculty for arousing anger. Drawing this same line of argument Socrates says that he prefers the term appetite to desire, for appetite implies both desire and non-desire. Non-will is just as an important concept for Plato as will. My revulsion at the idea of eating shit is stronger than my love of eating shell-fish. My will for wanting one thing is often measured alongside a will for not wanting something else. It is between will and non-will that choices are made, and preferences. Only a monster will desire everything, and there is another perversion: the culture that wants everything is a monstrous abomination. The natural thing (and this was Plato’s point), the authentically natural thing is that desire should be moderated by a courageous will to not-want, or want-less.

Nevertheless, in Fukuyama’s perverted misreading of Plato, thymus becomes a perfectly positive drive and one necessary for human satisfaction, in fact it is related by Fukuyama to human dignity.

Peter Sloterdijk sees thymus, and capitalism, from another angle. After locating the origin of the word thymus in a kind of receptacle through which the gods activated mankind, Sloterdijk suggests that we are still subject to thymotic power. But now it is via the State or the system that thymus returns to its receptacle like function. Instead of being activated by gods it is now programmed by the system. He says: “Current consumerism achieves, in a significant way, the same elimination of pride in favour of the erotic without holistic, altruistic and elegant excuses, by buying from man his interest in dignity, offering material favours in exchange.” The system now functions not as a body-snatcher, but as a dignity-snatcher: “In this way, the construct of the Homo-economicus, at first totally incredible, arrives at his goal of becoming the post-modern consumer. A simple consumer is he or she that doesn’t know or doesn’t want to know different appetites that… proceed from the erotic or demanding part of the soul.”

For Sloterdijk the rediscovery of the neo-thymotic human image in the Renaissance played an important role in the rise of the Nation State in terms of that which referred to its output. He lists Machiavelli, Hobbes, Rousseau, Adam Smith, Hamilton and Hegel as they who considered men’s passions as their most important qualities: their lust for fame, vanity, self-love, ambition and the desire to be recognised. All of them saw the dangers in their passions but most of them still dared to sell these vices as positive, productive aspects for society.

The thymotic drive is a creative, productive one, but it is also an angry, jealous, violent one. The will-to-want-more (Nietzschean) thymus coupled to the will-to-be-recognised (Hegelian) thymus is a pyrotechnic combination, an act of madness, throwing gunpowder into the fire. But it is what our system has always advocated. Sloterdijk makes a connection between Thymus and the Hippocratic temperament of Choleric. Both the will-to-want-more and the desire for recognition are areas in the thymotic field of psychology. They are questions of appetite and pride, of longing for success and fortune. Dreams: American Disneyland Dreams, fomented by the surplus-consumer society, our dynamic civilisation creating dynamic individuals from thymotic fantasies.

The greatest effect of the French Revolution, and the American War of Independence that preceded it, was not freedom, brotherhood and equality, but the creation of a dynamic civilisation based on the power of competitiveness, constantly fuelled by personal pride, needs for recognition, greedy ambition and motivating envy. It is these drives, applied to politics, which forces us to question our civilisation’s greatest apparent virtue – our liberal democracy.

“For the people, by the people”: by – to a certain, virtual extent; for – hardly.

Our party system is a reflection of our System, which is made of the essentially thymotic so necessary for making the market work in a dynamic way. Thus our parties are passionately competitive, power-hungry machines made up of power-hungry individuals. The parties themselves are divided into hungry factions, and each faction in ambitious individuals. How could we ever expect these vain-glorious competitors to even really care about those who voted for them except when it is useful? For the party to win it needs succulent policies and needs to sell those ideas seductively. It also needs the competitive, power hungry individuals to appear unified, and to seem to believe in the party principles. Principles that even the most utopian democrats will sacrifice to pragmatism. Over and over again the democratic politicians surprise us by their lack of vision, lack of principles and constant bowing to pragmatism.

Pragmatism is really the emergency exit out of all radical ideologies. In the great global liberal-free-market civilisation, political parties function very much like corporate groups. Voters are like customers for Coca-Cola or Pepsi: once they have been won to one side they will be more or less loyal forever. A loyal Coca-Cola consumer will rather have a Fanta than resort to Pepsi if there is no Coke. But more importantly than the loyalties it can create, modern politics is corporate through its internal competitiveness.

If Fukuyama would have been right and the triumph of liberalism had created a politically perfect system, there would no longer be any need for politics. But this is an absurd paradox. The liberal economic system needs competition. It is no surprise that the fall of communism left liberalism euphoric, but also momentarily crippled, and it was actually spiritually wavering until the Twin Towers came crashing down and the War on Terror began. It sounds like a conspiracy theory but for a system based on competition, struggle and ambition, war seems a logical necessity. And since the collapse of the Berlin Wall we have seen the liberal-democracies rushing headlong into almost any conflict that half-rears its head.

On a superficial level Fukuyama’s general thesis that liberal-democracy has triumphed as the only really viable and desirable political system is correct. Even those who don’t vote in the liberal-democrat systems would, if offered a choice, opt for the choice to vote. The grand majority of humankind want the voting option and therefore we can say that we want democracy. We also want all or some of the liberal ideas of freedom, although here we seem to split if we take the ballot-results as a fair measure between market-freedom and human-rights. The bi-partisan system of democracy is liberalism’s finest invention. By possessing its own inner competition it provides itself with its own self-criticism and its own renewal. Apart from the major options of right or left, the liberal-democratic system can offer a multitude of options for more socially complex societies: liberal-nationalism or liberal-catholicism, as well as free-market extremists and soft-core neo-fascisms.

On the surface it seems like a perfectly desirable system. Perfectly?: no, nothing is perfect. Triumphantly waiting it is, for the few last dictatorships to collapse and drop into liberal-democracy mode as well. When that happens it will be able to pronounce, with absolute conviction, that it is the perfect, and now the also the only system. But, ironically Fukuyama himself points to the liberal-democracies’ most dangerous foe. As the political systems to have fallen in the last half century have collapsed so suddenly, often without any pre-warning, taking us all by surprise, could the same happen to liberal-democracy?

Francis Fukuyama, THE END OF HISTORY AND THE LAST MAN, p. xviii

Peter Sloterdijk, ZORN UND SEIT, author’s own translation from the Spanish edition, p.27

PART TWO:

https://wordpress.com/post/pauladkin.wordpress.com/2485