Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 9

January 6, 2018

The Games We Play

The Girl and her boyfriend are upstairs playing on the X Box every boy seems to possess. There are sounds of rapid gunfire, the whine of fighter planes, pursuit vehicles, men's voices. I suspect that almost every household will have purchased some kind of game for Christmas, many of them digital, with enhanced CGI. They are frighteningly real. And most of them seem to involve killing on an industrial scale.

Two of the most reviewed games at the moment are Red Dead Redemption 2 (above) and the God of War series.

Not a woman in sight.

Not a woman in sight.

Decades ago there was a debate about whether watching violence on TV or on the cinema screen increased the tendency to violence on the street among young people. It ran alongside the debate on whether watching pornography made pedophiles and abusers more likely to abuse. I disagreed with censorship (still do) and thought, naively, that perhaps watching it got something out of the system that might otherwise have been performed in real life.

I don't think like that now. Playing violent games and killing people in a virtual reality somehow normalises it. And it decreases inhibition. In modern warfare there's little difference between pressing a button that wipes out an entire village and pressing a button on a console that fires a real missile that wipes out an entire village in an explosion you can watch on screen. It has no reality, no consequences for the button presser.

Some of our favourite TV programmes and films are so graphic, so violent, they're almost unwatchable. Many of them, as if to legitimise the action, are rooted in our blood-thirsty history, real or in some fictionalised past or future like Game of Thrones, Star Wars, Lord of the Rings. Even Harry Potter involves a lot of killing, which has a moral justification.

Missiles or dragons the result is the same.What is it about us, as a human race, that has such an obsession with killing other human beings, often in the most painful and horrific ways possible? Why do we venerate war and its 'heroes'? Why do we still go to war when there are so many civilised alternatives to settle our differences? Watching Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump waving their penile missiles at each other and boasting about who has the bigger button, chills me to the bone.

Missiles or dragons the result is the same.What is it about us, as a human race, that has such an obsession with killing other human beings, often in the most painful and horrific ways possible? Why do we venerate war and its 'heroes'? Why do we still go to war when there are so many civilised alternatives to settle our differences? Watching Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump waving their penile missiles at each other and boasting about who has the bigger button, chills me to the bone.

My partner, who is a peaceable sort of bloke, commented, 'Where are the games that grow relationships?' It set me thinking. Where are the games that set challenges people are likely to encounter in real life? Surviving a plane crash, a tsunami, shipwreck, escaping from tigers in the wilderness, or saving the planet - without having to kill people? Games that nurture the other side of human nature - the constructive, empathetic side.

The problem with individuals (regrettably almost always men) who crave power in order to dominate, control and sometimes abuse others - men like Harvey Weinstein, Jimmy Savile, Joseph Stalin, Kim Jong Un, Alexander the Great, Attila the Hun, Vlad the Impaler - men we allow to have that power - have to be confronted. All that testosterone, all that money, all those weapons.

The human consequence of war.Genetic anthropologists say that there were probably about 15 species of human being on the planet originally, where now there is only one. Us. We have dug up the remains of at least 3 others, so we can presume that they are right. What happened to these other species? Are we a branch of the human tree so aggressive that we wiped them all out? All I can say is that, looking at human history, both past and present, the ancient human being sitting in his cave eating fish and peacefully raising his children, would not have stood a chance against Us. We'd have killed him and his male relatives, raped their wives, eaten their fish, taken over the cave with a sea view and kept the most personable of their children as slaves. Much as we do now.

The human consequence of war.Genetic anthropologists say that there were probably about 15 species of human being on the planet originally, where now there is only one. Us. We have dug up the remains of at least 3 others, so we can presume that they are right. What happened to these other species? Are we a branch of the human tree so aggressive that we wiped them all out? All I can say is that, looking at human history, both past and present, the ancient human being sitting in his cave eating fish and peacefully raising his children, would not have stood a chance against Us. We'd have killed him and his male relatives, raped their wives, eaten their fish, taken over the cave with a sea view and kept the most personable of their children as slaves. Much as we do now.

Wicked Game from Peaky Blinders.

With climate change staring us in the face, we are being told by experts that war is increasingly likely over scarce resources. I would like to think we can all cooperate to solve the biggest crisis the human race has ever faced - one that could, according to some scientists, result in our extinction. On present showing there isn't much cause for optimism. Can we change? Can we raise our children to be more empathetic and less aggressive? Do the games we play affect how we act in real life?

Two of the most reviewed games at the moment are Red Dead Redemption 2 (above) and the God of War series.

Not a woman in sight.

Not a woman in sight.Decades ago there was a debate about whether watching violence on TV or on the cinema screen increased the tendency to violence on the street among young people. It ran alongside the debate on whether watching pornography made pedophiles and abusers more likely to abuse. I disagreed with censorship (still do) and thought, naively, that perhaps watching it got something out of the system that might otherwise have been performed in real life.

I don't think like that now. Playing violent games and killing people in a virtual reality somehow normalises it. And it decreases inhibition. In modern warfare there's little difference between pressing a button that wipes out an entire village and pressing a button on a console that fires a real missile that wipes out an entire village in an explosion you can watch on screen. It has no reality, no consequences for the button presser.

Some of our favourite TV programmes and films are so graphic, so violent, they're almost unwatchable. Many of them, as if to legitimise the action, are rooted in our blood-thirsty history, real or in some fictionalised past or future like Game of Thrones, Star Wars, Lord of the Rings. Even Harry Potter involves a lot of killing, which has a moral justification.

Missiles or dragons the result is the same.What is it about us, as a human race, that has such an obsession with killing other human beings, often in the most painful and horrific ways possible? Why do we venerate war and its 'heroes'? Why do we still go to war when there are so many civilised alternatives to settle our differences? Watching Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump waving their penile missiles at each other and boasting about who has the bigger button, chills me to the bone.

Missiles or dragons the result is the same.What is it about us, as a human race, that has such an obsession with killing other human beings, often in the most painful and horrific ways possible? Why do we venerate war and its 'heroes'? Why do we still go to war when there are so many civilised alternatives to settle our differences? Watching Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump waving their penile missiles at each other and boasting about who has the bigger button, chills me to the bone.My partner, who is a peaceable sort of bloke, commented, 'Where are the games that grow relationships?' It set me thinking. Where are the games that set challenges people are likely to encounter in real life? Surviving a plane crash, a tsunami, shipwreck, escaping from tigers in the wilderness, or saving the planet - without having to kill people? Games that nurture the other side of human nature - the constructive, empathetic side.

The problem with individuals (regrettably almost always men) who crave power in order to dominate, control and sometimes abuse others - men like Harvey Weinstein, Jimmy Savile, Joseph Stalin, Kim Jong Un, Alexander the Great, Attila the Hun, Vlad the Impaler - men we allow to have that power - have to be confronted. All that testosterone, all that money, all those weapons.

The human consequence of war.Genetic anthropologists say that there were probably about 15 species of human being on the planet originally, where now there is only one. Us. We have dug up the remains of at least 3 others, so we can presume that they are right. What happened to these other species? Are we a branch of the human tree so aggressive that we wiped them all out? All I can say is that, looking at human history, both past and present, the ancient human being sitting in his cave eating fish and peacefully raising his children, would not have stood a chance against Us. We'd have killed him and his male relatives, raped their wives, eaten their fish, taken over the cave with a sea view and kept the most personable of their children as slaves. Much as we do now.

The human consequence of war.Genetic anthropologists say that there were probably about 15 species of human being on the planet originally, where now there is only one. Us. We have dug up the remains of at least 3 others, so we can presume that they are right. What happened to these other species? Are we a branch of the human tree so aggressive that we wiped them all out? All I can say is that, looking at human history, both past and present, the ancient human being sitting in his cave eating fish and peacefully raising his children, would not have stood a chance against Us. We'd have killed him and his male relatives, raped their wives, eaten their fish, taken over the cave with a sea view and kept the most personable of their children as slaves. Much as we do now.Wicked Game from Peaky Blinders.

With climate change staring us in the face, we are being told by experts that war is increasingly likely over scarce resources. I would like to think we can all cooperate to solve the biggest crisis the human race has ever faced - one that could, according to some scientists, result in our extinction. On present showing there isn't much cause for optimism. Can we change? Can we raise our children to be more empathetic and less aggressive? Do the games we play affect how we act in real life?

Published on January 06, 2018 05:59

January 2, 2018

Thoughts at the Turning of the Year

At about 9pm on December the 31st my mother would get out the ginger wine. My father would be listening to Jimmy Shand playing Scottish music on the radio and he and my mother would dance the Gay Gordons round the living room - perhaps an effect of the ginger wine. My parents - teetotal Methodists - were convinced that ginger wine was non alcoholic - likewise the neighbour's home made blackcurrant liqueur which had a kick like a shire horse.

If the weather was fine, some of our neighbours from across the fellside might walk over for mince pies and Christmas cake and a glass of a supposedly non-alcoholic beverage. My father, a congenital arsonist if ever there was such a thing, would have a roaring fire going in the black range. Sometimes it was so hot the metal glowed, almost transparent.

When midnight boomed from the radio, we would all join hands and sing Auld Lang Syne before my father went outside with the salt cellar, a piece of bread, and a glass of ginger wine. Then he would put a piece of coal in his pocket from the shed and come back into the house. He was a corn gold Irishman, not the dark first-foot required by the myth. My superstitious grandmother was convinced that that was the cause of our bad luck on the farm. If my grandparents happened to be staying with us, my Tyneside Italian grandfather would be made to do the honours. It must never be a woman - that was very bad luck indeed. The year my grandmother accidentally came in first became the year my grandfather died.

Only when the first-foot had safely crossed the threshold were the rest of us allowed out into the yard to look at the stars, wincing from the cold. It was a moment that felt hugely significant. I remember being full of anticipation at what this wonderful new year might bring. It was a blank page to be written on, a space for optimistic dreaming. For my mother it was different - she used to talk about the war; about spending New Year in a bomb shelter; about watching London burn when she went to join her first husband for his embarkation leave. And she would shed tears and remember David in his iron tomb at the bottom of the South Atlantic. I was sometimes impatient with her, in that unthinking way that children have, because I loved my father and felt a deep loyalty towards him.

Back inside again, there was the ceremony of changing the calendar on the kitchen wall, opening it to the first page of the new year. Upstairs in my bedroom I would collect together all my little bits of memorabilia - birthday cards, photographs, postcards, letters, programmes - and put them into a chocolate box. Then I would write the date on the lid and tie it up with ribbon. I still have the memorabilia, now pasted into scrap books, and the memories of New Year spent on that remote hill farm in the Lake District.

I always find it strange that so much stress is put on the 31st December, the last day of the Gregorian Calendar, when, in practice, we step into a new year every day of our lives and there are two other major calendar systems in the world (Chinese and Islamic) that celebrate a new year at very different times. The Gregorian Calendar was introduced by Pope Gregory in October 1582 to replace the inaccurate Julian Calendar as a way of reconciling the differences between the 12 month organisational calendar and the lunar cycle - in the Christian church the celebration of Easter is still calculated by the lunar cycle. The flawed 12 month Julian calendar had a 10 month Roman predecessor with an 8 day week and some unspecified winter period to even up the earth's 365.24 day rotation round the sun. The Gregorian Calendar introduced the idea of the Leap Year to round it out every four years. It's all a bit of a mess with a bit of fudging round the edges.

So why don't we use the Lunar Cycle as a means of organising yearly events? Our lives are governed by the sun and the moon - and the earth's circuit round the sun is perfectly rhythmic without our little adjustments. Why aren't we celebrating the real turning of the year on December the 21st rather than an artificial date 10 days later?

Globalisation means that the Chinese and Islamic calendars, both based on the lunar cycle, are increasingly giving way to the Gregorian, which means that New Year fireworks go off in almost every country of the world at midnight on December 31st. I watched them on television. But this year there was no sense of anticipation, just a feeling of existential dread. With Trump in the White House, Brexit on the horizon, half the world in turmoil, millions in refugee camps, there didn't seem much to celebrate. Anyone else feeling like this?

If the weather was fine, some of our neighbours from across the fellside might walk over for mince pies and Christmas cake and a glass of a supposedly non-alcoholic beverage. My father, a congenital arsonist if ever there was such a thing, would have a roaring fire going in the black range. Sometimes it was so hot the metal glowed, almost transparent.

When midnight boomed from the radio, we would all join hands and sing Auld Lang Syne before my father went outside with the salt cellar, a piece of bread, and a glass of ginger wine. Then he would put a piece of coal in his pocket from the shed and come back into the house. He was a corn gold Irishman, not the dark first-foot required by the myth. My superstitious grandmother was convinced that that was the cause of our bad luck on the farm. If my grandparents happened to be staying with us, my Tyneside Italian grandfather would be made to do the honours. It must never be a woman - that was very bad luck indeed. The year my grandmother accidentally came in first became the year my grandfather died.

Only when the first-foot had safely crossed the threshold were the rest of us allowed out into the yard to look at the stars, wincing from the cold. It was a moment that felt hugely significant. I remember being full of anticipation at what this wonderful new year might bring. It was a blank page to be written on, a space for optimistic dreaming. For my mother it was different - she used to talk about the war; about spending New Year in a bomb shelter; about watching London burn when she went to join her first husband for his embarkation leave. And she would shed tears and remember David in his iron tomb at the bottom of the South Atlantic. I was sometimes impatient with her, in that unthinking way that children have, because I loved my father and felt a deep loyalty towards him.

Back inside again, there was the ceremony of changing the calendar on the kitchen wall, opening it to the first page of the new year. Upstairs in my bedroom I would collect together all my little bits of memorabilia - birthday cards, photographs, postcards, letters, programmes - and put them into a chocolate box. Then I would write the date on the lid and tie it up with ribbon. I still have the memorabilia, now pasted into scrap books, and the memories of New Year spent on that remote hill farm in the Lake District.

I always find it strange that so much stress is put on the 31st December, the last day of the Gregorian Calendar, when, in practice, we step into a new year every day of our lives and there are two other major calendar systems in the world (Chinese and Islamic) that celebrate a new year at very different times. The Gregorian Calendar was introduced by Pope Gregory in October 1582 to replace the inaccurate Julian Calendar as a way of reconciling the differences between the 12 month organisational calendar and the lunar cycle - in the Christian church the celebration of Easter is still calculated by the lunar cycle. The flawed 12 month Julian calendar had a 10 month Roman predecessor with an 8 day week and some unspecified winter period to even up the earth's 365.24 day rotation round the sun. The Gregorian Calendar introduced the idea of the Leap Year to round it out every four years. It's all a bit of a mess with a bit of fudging round the edges.

So why don't we use the Lunar Cycle as a means of organising yearly events? Our lives are governed by the sun and the moon - and the earth's circuit round the sun is perfectly rhythmic without our little adjustments. Why aren't we celebrating the real turning of the year on December the 21st rather than an artificial date 10 days later?

Globalisation means that the Chinese and Islamic calendars, both based on the lunar cycle, are increasingly giving way to the Gregorian, which means that New Year fireworks go off in almost every country of the world at midnight on December 31st. I watched them on television. But this year there was no sense of anticipation, just a feeling of existential dread. With Trump in the White House, Brexit on the horizon, half the world in turmoil, millions in refugee camps, there didn't seem much to celebrate. Anyone else feeling like this?

Published on January 02, 2018 03:43

December 29, 2017

New Year Poem: Hunters by Pauline Yarwood

The page will have to be turned in the end.

Every year the unwanted pictorial calendar

and every year the predictable January Breugel.

Just now, for a while longer,

I'm grabbing on to the tail end

of the year I already have.

There's comfort here, warmth, and colour,

months to mull over, summer's music to remember,

a year, a beautiful year, safely lived.

Turn the page and you're up against it -

snow scene, skaters, country life pulling together,

the expectant glow of fresh starts.

I don't want a fresh start.

I want more of the same.

Look. There's a darkening sky and

darker waters, the snow-laden deadening,

leadening of a life harshly lived.

And those hunters and dogs.

What are they hunting

exactly?

Copyright Pauline Yarwood

from Image Junkie, Wayleaves Press, 2017

I too, have an ambiguous relationship with calendars. At home, when I was a child, there was a ceremonial changing of the calendar after the clock had struck 12 on New Year's Eve. The coming year was a blank; something to anticipate - something to dread. My father would step out into the starlit farmyard to bring in his piece of coal and then we would all go out and look at the sky as if it could tell us what the coming year would bring. Then we would go back into the kitchen to sit around the big black range with its roaring fire to get warm again. Comfort and security, with a whole, dark, unknown universe on the other side of the door.

What will next year bring, I wonder?

Image Junkie is published by Wayleaves Press.

Published on December 29, 2017 03:45

December 18, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Winter Light

Horizontal strobes

across the russeting slope

disclose the contours of the land

the fierce geography of rock

the patterning of sheep through bracken

lipped water-marks on sand

The mountain’s shadow

bruises the lake.

The season is wintering in

and the cold is like loss:

a cramping hold on bone

muscle, thought, spilling in

from the east.

The air tastes metallic

like snow dissolving on the tongue.

This is the death month

December's Druid alphabet

that signified

the rebirth of the spirit.

Ash trees clumsy with unshed seeds,

a deer’s tooth grooving the bark.

I glimpse a snowdrop spiking up

through a dead leaf

before the falling sun herds

us into the longest night.

© Kathleen Jones

From Not Saying Goodbye at Gate 21, Templar Poetry Image courtesy of ABSFreePic.com

A peaceful Solstice and a very merry Christmas to everyone!

Published on December 18, 2017 16:30

December 11, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Two Spells for Sleeping by Michael Donaghy

Eight white stones

in a moonlit garden,

to carry her safe

across the bracken

on a gravel path

like a silvery ribbon

seven eels in the urge of water

a necklace in rhyme

to help her remember

a river to carry her

unheard laughter

to light about her

weary mirror

six candles for a king's daughter

five sighs for a drooping head

a prayer to be whispered

a book to be read

four ghosts to gentle her bed

three owls in the dusk falling

what is that name you hear them calling?

In the soft dark welling,

two tales to be telling,

one spell for sleeping,

one for kissing,

for leaving.

© The Estate of Michael Donaghy 2005

From 'Safest', published by Picador, London 2005

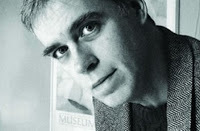

This is the last poem in Michael Donaghy's final collection, published posthumously. I love its simplicity, the feeling of nursery rhyme or folk tale - the mysterious princess gazing in her 'weary mirror' - the four ghosts that 'gentle her bed' and that nocturnal prognosticator, the owl who cries 'Who?' In some cultures it is the foreteller of death. In the poem, as in most traditional folk tales there's the sense of a journey about to begin, a leave-taking. For Michael Donaghy it was the ultimate leave-taking.

Michael died suddenly, from a brain haemorrhage, in 2004 aged 50. He was Irish-American, brought up in New York, in the Bronx, where he witnessed endemic racism and every-day violence. Even as a young child he was drawn to books, spending time in the library rather than on the streets. He later said, “I owe everything I know about poetry to the public library system.” He went to university (which he referred to as his ‘miseducation’) and by the time he was in his early twenties he was the editor of the Chicago Review. Michael was also a musician and, when he moved to London in 1985, he joined Don Paterson and jazz musician Tim Garland to form the fusion music group ‘Lammas’, which is where I first encountered his work.

I love this collection and feel sad that his enormous talent has been lost, though Michael never lived life in safe mode.

I reviewed 'Safest' here.

in a moonlit garden,

to carry her safe

across the bracken

on a gravel path

like a silvery ribbon

seven eels in the urge of water

a necklace in rhyme

to help her remember

a river to carry her

unheard laughter

to light about her

weary mirror

six candles for a king's daughter

five sighs for a drooping head

a prayer to be whispered

a book to be read

four ghosts to gentle her bed

three owls in the dusk falling

what is that name you hear them calling?

In the soft dark welling,

two tales to be telling,

one spell for sleeping,

one for kissing,

for leaving.

© The Estate of Michael Donaghy 2005

From 'Safest', published by Picador, London 2005

This is the last poem in Michael Donaghy's final collection, published posthumously. I love its simplicity, the feeling of nursery rhyme or folk tale - the mysterious princess gazing in her 'weary mirror' - the four ghosts that 'gentle her bed' and that nocturnal prognosticator, the owl who cries 'Who?' In some cultures it is the foreteller of death. In the poem, as in most traditional folk tales there's the sense of a journey about to begin, a leave-taking. For Michael Donaghy it was the ultimate leave-taking.

Michael died suddenly, from a brain haemorrhage, in 2004 aged 50. He was Irish-American, brought up in New York, in the Bronx, where he witnessed endemic racism and every-day violence. Even as a young child he was drawn to books, spending time in the library rather than on the streets. He later said, “I owe everything I know about poetry to the public library system.” He went to university (which he referred to as his ‘miseducation’) and by the time he was in his early twenties he was the editor of the Chicago Review. Michael was also a musician and, when he moved to London in 1985, he joined Don Paterson and jazz musician Tim Garland to form the fusion music group ‘Lammas’, which is where I first encountered his work.

I love this collection and feel sad that his enormous talent has been lost, though Michael never lived life in safe mode.

I reviewed 'Safest' here.

Published on December 11, 2017 16:30

December 5, 2017

The Leaving of Italy

The little house in the olive grove - last view.

The little house in the olive grove - last view. from the terrace looking towards Capezzano Monte - our villageLeaving anywhere is difficult - leaving a place like this is very hard. The little house in the olive grove has been home to my partner Neil for 6 years and it was also mine for 3 or them. though I've been living back in the UK for the last 3 years the little house was always there to visit - to drink wine on the terrace looking out over the Mediterranean towards Corsica, or to look up at the rocky, white-tipped Alpi Apuane rearing more than 4,000 feet above us.

from the terrace looking towards Capezzano Monte - our villageLeaving anywhere is difficult - leaving a place like this is very hard. The little house in the olive grove has been home to my partner Neil for 6 years and it was also mine for 3 or them. though I've been living back in the UK for the last 3 years the little house was always there to visit - to drink wine on the terrace looking out over the Mediterranean towards Corsica, or to look up at the rocky, white-tipped Alpi Apuane rearing more than 4,000 feet above us. The Alpi Apuane behind us

The Alpi Apuane behind us

sunset in the Mediterranean from our terraceThen there were the eagles and the wild boar, ghiri, pine martens, porcupines,foxes and badgers, all managing to survive the Italian compulsion to shoot things. They don't use pesticides up here on the mountain, so the wild flowers in spring were sensational enough to make you weep for what we have lost here in the UK.

sunset in the Mediterranean from our terraceThen there were the eagles and the wild boar, ghiri, pine martens, porcupines,foxes and badgers, all managing to survive the Italian compulsion to shoot things. They don't use pesticides up here on the mountain, so the wild flowers in spring were sensational enough to make you weep for what we have lost here in the UK. A ghiro

A ghiro

Wild flowers everywhereBut Brexit has changed everything. The marble sculpting industry has been in decline for a decade or more as economic forces have bitten deep into the pockets of purchasers. It has become difficult for artists to get grants and there are fewer public art commissions to apply for. Brexit just put the lid on an already struggling market. In 2009 there were about 15 working studios in the centre of Pietrasanta - now there are only a couple left. It can no longer justify its title of 'City of the Arts', with a tradition going back to Michelangelo.

Wild flowers everywhereBut Brexit has changed everything. The marble sculpting industry has been in decline for a decade or more as economic forces have bitten deep into the pockets of purchasers. It has become difficult for artists to get grants and there are fewer public art commissions to apply for. Brexit just put the lid on an already struggling market. In 2009 there were about 15 working studios in the centre of Pietrasanta - now there are only a couple left. It can no longer justify its title of 'City of the Arts', with a tradition going back to Michelangelo.  Neil sculpting in his studio in winter - covered in marble dust!Costs have risen exponentially since the banking crisis - accommodation, food, power, transport fees, even the cost of the marble itself. The current state of the pound against the euro means that a tiny apartment that cost about £350 a month in 2011 now costs £500. In the centre of town it will cost you £750.

Neil sculpting in his studio in winter - covered in marble dust!Costs have risen exponentially since the banking crisis - accommodation, food, power, transport fees, even the cost of the marble itself. The current state of the pound against the euro means that a tiny apartment that cost about £350 a month in 2011 now costs £500. In the centre of town it will cost you £750. Neil at the Mt Corchia marble quarryIt has been hard packing up belongings and giving away what can't be brought home. I won't miss the winter damp that brings a black bloom to the walls and ceilings high on the mountains - the dreaded 'Mufa'. And I won't miss the rural Italian disregard for comfort - the plumbing that never works properly, the cold, hard tiled floors, or the scorching summers when the Sirocco blows from Africa and frizzles everything in sight.

Neil at the Mt Corchia marble quarryIt has been hard packing up belongings and giving away what can't be brought home. I won't miss the winter damp that brings a black bloom to the walls and ceilings high on the mountains - the dreaded 'Mufa'. And I won't miss the rural Italian disregard for comfort - the plumbing that never works properly, the cold, hard tiled floors, or the scorching summers when the Sirocco blows from Africa and frizzles everything in sight. A wildfire at the bottom of the olive grove below our house...I will also miss the thunderstorms that covered the whole sky with fireworks (our house was struck once). We've experienced hurricanes and earthquakes and weather bombs that washed away the road. Italy is spectacular in every way!

A wildfire at the bottom of the olive grove below our house...I will also miss the thunderstorms that covered the whole sky with fireworks (our house was struck once). We've experienced hurricanes and earthquakes and weather bombs that washed away the road. Italy is spectacular in every way! A thunderstorm coming in off the sea

A thunderstorm coming in off the sea Road slipping down the mountainside after a weather bomb - it vanished completely the next dayI will also miss the friends I've made over the years, though I hope to still see them on visits.

Road slipping down the mountainside after a weather bomb - it vanished completely the next dayI will also miss the friends I've made over the years, though I hope to still see them on visits.  eating with friends on the terraceAs we drove down the tortuous mountain road for the last time on the way to Pisa airport before dawn, we met two huge porcupines waddling towards us under a waving cloud of barbed spines. I won't see them at the Mill or glimpse a wild boar in the undergrowth, sadly.

eating with friends on the terraceAs we drove down the tortuous mountain road for the last time on the way to Pisa airport before dawn, we met two huge porcupines waddling towards us under a waving cloud of barbed spines. I won't see them at the Mill or glimpse a wild boar in the undergrowth, sadly.

Published on December 05, 2017 05:50

November 21, 2017

The Red Beach Hut by Lynn Michell

I've not had much time for reading recently, but this is the book that has been keeping me awake at night. Absorbing from the first page, the prose is spare, conveying with the utmost delicacy the fragility of the characters’ situation and their states of mind. Inspirational is an overused word these days, but this novel is just that.

The Red Beach Hut

is the story of an innocent, redemptive relationship between a man and a boy which is misinterpreted by onlookers with a prejudiced, tabloid mentality.

I've not had much time for reading recently, but this is the book that has been keeping me awake at night. Absorbing from the first page, the prose is spare, conveying with the utmost delicacy the fragility of the characters’ situation and their states of mind. Inspirational is an overused word these days, but this novel is just that.

The Red Beach Hut

is the story of an innocent, redemptive relationship between a man and a boy which is misinterpreted by onlookers with a prejudiced, tabloid mentality.Abbott, the man, has crashed out of his professional role, burnt out, after being the victim of a homophobic attack. Neville is 8 years old and wanders the beach alone while his mother plays hostess to clients in their tiny flat - men he is afraid of He is on the ‘at risk’ register.

The setting - an ordinary seaside town with its row of colourful beach huts along the shore - is also a character in the book - one that interacts with each of the other characters in turn. I could smell the sea, hear it crashing on the rocks as I read, and felt it echoing the ebb and flow of the narrative.

When Abbott comes to stay in the red beach hut, Neville is curious about the newcomer. Both recognise the loneliness and isolation in the other and are drawn together. We, as readers, don’t know how the story is going to develop and feel the threat of outside pressure. An innocent relationship can be broken so easily by the kind of prejudice and fear stirred up in this age of media frenzy. This is the age of Trumpism, the rise of the alt-right, the media lynch mob, a world where racism, homophobia and misogyny have been normalised. People like Abbott, Neville and his mother have a difficult time in 2017.

There's a sense of menace, right from the beginning, when Neville walks alone along the edge of the sea in the fading evening light.

'At the very end of the curved bay, a stack of sharp-tipped black rocks jutted up in groups of four and five and six. Like sentinels marching backwards into the sea. Water burst and broke over them, blocking Neville's way to the next smaller cove. Only at very low tide, when the pools ran quietly, was he daring enough to walk through and around them on puddled sand while he held his breath and counted his steps because it was dangerous. In the next cove was a gaping, echoing cave whose roof leaned out like a canopy towards the sea. He'd been inside and shouted and heard his voice bounce back to him. If the sea ran inside too soon, he'd be trapped.'

Neville counts everything, but is sometimes defeated. When Abbott finds Neville trying to count grains of sand and the boy turns his 'troubled grey eyes' on him and asks a question, the man's first instinct is to walk away, but:

'When he looked into the boy's face he observed and judged that the child was vulnerable, sensitive, observant and wise beyond his years. Reading boys' faces had been his trade for a very long time and he was good at it. In a heartbeat, Abbott was jettisoned back into one of those anonymous, grimly furnished rooms in which a truculent young person sat on the other side of a scabbed table, big trainers sticking out on the Lino floor while he searched for a small crack in a long-formed, anger-hardened shell of defence. To offer a response to a troubled child was a habit too deeply ingrained for him to ignore. He gave. He helped. He listened. He held out a hand. He was known among his colleagues to be one of the best.'

The Red Beach Hut is a beautifully written exploration of the relationship between a tormented man and a damaged boy. The author moves seamlessly between them. Getting inside a child’s mind isn’t easy, but Michell gives us Neville’s point of view in a way that is guileless and utterly credible. The ending could so easily have been unsatisfactory, but it was perfect - understated and exactly right. No spoilers! I wish there were more novels like this.

Lynn Michell is the editor of Linen Press, a small award-winning publisher featuring work by women - now the only women’s press in Britain. She knows what makes a good novel, both in the writing and in the editing.

The Red Beach Hut is published by Inspired Quill and is available direct from the publisher or through Amazon.

Published on November 21, 2017 05:46

November 14, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Ode to Twining by Katie Hale

The week summer slammed the door so hard the valley

rumbled from its leaving, you couldn’t move for moaning.

Not fat complaints dropping powerless from lips,

or torrents gossiping and coarse – up here,

our words are leaner, tighter… Here we twine,

unwinding our moans like wool

festooned between us. When the weather

rocked the windows and swept away the bins,

we twined till twining became

entwining, till we had twilled ourselves

in the warp and weft of our words –

the way we were that other winter, when water

rose through the town and the roads were a maze,

when the rain was a blank wall

wetting our backs and the wind was a wild thing,

when our words unravelled and all we could do was follow them

like string – till together our twinings wound thicker,

were rope, and we bound ourselves together like love

as the floodwater billowed and swept –

and we stood fast in our twining and we waited, and we won.

Copyright Katie Hale 2017

Reproduced with the permission of the author.

This poem, by Cumbrian poet Katie Hale, was commissioned by the BBC as part of a series of poems about dialect words on the BBC website during National Poetry Week. Katie was given a collection of Cumbrian words and chose 'twining' which, up here in the Lake District, means moaning or complaining. If you're 'twining on' you're being 'a right pain'. Whining might be nearer to the actual meaning as alternatives sound too polite!

You can hear Katie reading the poem here on the website.

Katie Hale photographed by Sepal Desai

Katie Hale photographed by Sepal Desai

Katie Hale is one of the young northern poets taking over the poetry scene. Her name has featured often in the lists of prize-winning poets, including the prestigious Ballymaloe International prize. She co-authored an award-winning musical at the Edinburgh Festival in August, the Inevitable Quiet of the Crash, and is being mentored by Penguin with her first novel. She is a name to look out for. Her first pamphlet was published this year by Flap. It's called, appropriately, Breaking the Surface. It's contents are sometimes dark. Eat Your Heart Out is a graphic riff on a saying we use without thinking about its literal meaning. The wild is never far away - there are wolves and ravens, mermaids and sirens, things concealed that can never be told. There are echoes of old mythologies, fairy tales (the ones without fairies) and a constant reminder of the dark side of human nature. One of my favourite poems is Secret.

Against all odds, we keep her

locked in the dark space under the house.

It's a joint effort.

You bind her hands in complex knots

(it has been suggested she has the ability to pick locks),

chain one ankle to the ground.

I cover her with a blanket

to muffle her tinny, mewling sounds.

We feed her as seldom as possible.

We stop inviting the neighbours round,

change all our privacy settings to invisible.

We cut the phone line, lock the door,

nail the floorboards over our mouths.

Copyright Katie Hale 2017

Find out more on Katie Hale's website

and buy Breaking the Surface here.

rumbled from its leaving, you couldn’t move for moaning.

Not fat complaints dropping powerless from lips,

or torrents gossiping and coarse – up here,

our words are leaner, tighter… Here we twine,

unwinding our moans like wool

festooned between us. When the weather

rocked the windows and swept away the bins,

we twined till twining became

entwining, till we had twilled ourselves

in the warp and weft of our words –

the way we were that other winter, when water

rose through the town and the roads were a maze,

when the rain was a blank wall

wetting our backs and the wind was a wild thing,

when our words unravelled and all we could do was follow them

like string – till together our twinings wound thicker,

were rope, and we bound ourselves together like love

as the floodwater billowed and swept –

and we stood fast in our twining and we waited, and we won.

Copyright Katie Hale 2017

Reproduced with the permission of the author.

This poem, by Cumbrian poet Katie Hale, was commissioned by the BBC as part of a series of poems about dialect words on the BBC website during National Poetry Week. Katie was given a collection of Cumbrian words and chose 'twining' which, up here in the Lake District, means moaning or complaining. If you're 'twining on' you're being 'a right pain'. Whining might be nearer to the actual meaning as alternatives sound too polite!

You can hear Katie reading the poem here on the website.

Katie Hale photographed by Sepal Desai

Katie Hale photographed by Sepal DesaiKatie Hale is one of the young northern poets taking over the poetry scene. Her name has featured often in the lists of prize-winning poets, including the prestigious Ballymaloe International prize. She co-authored an award-winning musical at the Edinburgh Festival in August, the Inevitable Quiet of the Crash, and is being mentored by Penguin with her first novel. She is a name to look out for. Her first pamphlet was published this year by Flap. It's called, appropriately, Breaking the Surface. It's contents are sometimes dark. Eat Your Heart Out is a graphic riff on a saying we use without thinking about its literal meaning. The wild is never far away - there are wolves and ravens, mermaids and sirens, things concealed that can never be told. There are echoes of old mythologies, fairy tales (the ones without fairies) and a constant reminder of the dark side of human nature. One of my favourite poems is Secret.

Against all odds, we keep her

locked in the dark space under the house.

It's a joint effort.

You bind her hands in complex knots

(it has been suggested she has the ability to pick locks),

chain one ankle to the ground.

I cover her with a blanket

to muffle her tinny, mewling sounds.

We feed her as seldom as possible.

We stop inviting the neighbours round,

change all our privacy settings to invisible.

We cut the phone line, lock the door,

nail the floorboards over our mouths.

Copyright Katie Hale 2017

Find out more on Katie Hale's website

and buy Breaking the Surface here.

Published on November 14, 2017 07:59

October 31, 2017

Tuesday Poem - Her Kind by Anne Sexton

I have gone out, a possessed witch,

haunting the black air, braver at night;

dreaming evil, I have done my hitch

over the plain houses, light by light:

lonely thing, twelve-fingered, out of mind.

A woman like that is not a woman, quite.

I have been her kind.

I have found the warm caves in the woods,

filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves,

closets, silks, innumerable goods;

fixed the suppers for the worms and the elves:

whining, rearranging the disaligned.

A woman like that is misunderstood.

I have been her kind.

I have ridden in your cart, driver,

waved my nude arms at villages going by,

learning the last bright routes, survivor

where your flames still bite my thigh

and my ribs crack where your wheels wind.

A woman like that is not ashamed to die.

I have been her kind.

Anne Sexton

1928-1974

from The Complete Poems of Anne Sexton,

© Linda Gray Sexton

I like this poem because it connects with Virginia Woolf’s observation that women who wrote, in the past, would have been classified as mad, or witches, or both because it was not appropriate for a woman to be a writer. "Any woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would certainly have gone crazed, shot herself, or ended her days in some lonely cottage outside the village, half witch, half wizard, feared and mocked at."* When I wrote the biography of an early woman writer, Margaret Cavendish, who dared to publish her work in the 17th century, I was disturbed to discover that she was known (according to Samuel Pepys) as ‘Mad Madge’. Contemporary thinking was that if you weren’t mad before you wrote anything, the very act of writing would send a fragile woman’s mind and body out of kilter. You risked madness and sterility.

1451 - Le Champion des Dames Poetry is a little like witchcraft, whether practised by men or women - the alchemy of words. This was Anne Sexton's 'signature poem' - the one she opened her readings with, so it is a powerful statement of how she saw herself. Anne Sexton is one of the USA’s best known poets, usually classified with the ‘confessional’ poets. It was very controversial at the time to write so frankly about personal experience, particularly about mental health problems and sex. Her first collection ‘To Bedlam and Halfway Back’ was published in 1960, attracting a great deal of attention. Anne Sexton suffered from post-natal depression after the births of both her children and never completely recovered. She was sectioned more than once. Her fragile mental health has been described by her daughter, Linda Gray Sexton, in

‘Searching for Mercy Street’

and also in her

biography by Diane Wood Middlebrook

. Anne Sexton committed suicide in 1974.

1451 - Le Champion des Dames Poetry is a little like witchcraft, whether practised by men or women - the alchemy of words. This was Anne Sexton's 'signature poem' - the one she opened her readings with, so it is a powerful statement of how she saw herself. Anne Sexton is one of the USA’s best known poets, usually classified with the ‘confessional’ poets. It was very controversial at the time to write so frankly about personal experience, particularly about mental health problems and sex. Her first collection ‘To Bedlam and Halfway Back’ was published in 1960, attracting a great deal of attention. Anne Sexton suffered from post-natal depression after the births of both her children and never completely recovered. She was sectioned more than once. Her fragile mental health has been described by her daughter, Linda Gray Sexton, in

‘Searching for Mercy Street’

and also in her

biography by Diane Wood Middlebrook

. Anne Sexton committed suicide in 1974.Anne Sexton: The Complete Poems, Houghton Mifflin, 1999

* Virginia Woolf, A Room of One's Own, Ch.3.

Published on October 31, 2017 11:00

October 30, 2017

The Bureaucracy of Chaos

So much has been happening in my life I don't know where to begin. A month ago I went to Manchester Airport at very short notice to meet a 16 year old girl who walked out of the arrivals door and into my life. She now lives in my spare room. Having a teenager in the house changes everything, particularly one who has been living in a third world country for a while and has no suitable clothing for the British winter, or an inner thermostat to cope with the plunge in temperatures. It's a while since I was a Mum and I'd forgotten the taxi service, the bank of mum and dad, the expectation of room service and the alternative body clock! Apart from that (well, even including that!) she is a joy.

the Girl herself

the Girl herself

But I have had to get to grips with the bureaucracy of the Welfare State, which - I have to tell you - is mis-named. Welfare it is not. There are forms for everything - most of them pages long. The telephone helplines are interminable and expensive. The jargon is impenetrable and the Citizen's Advice Bureau totally unable to cope with the demand from tired, frustrated, and often distressed, people. At 16, if you can't live with your parents and they aren't willing to support you, you fall between two categories - you're too old to be taken into care, but you don't automatically get any state support. I'm beginning to realise why so many young people are sleeping rough. There also appears to be no system whereby grandparents can be supported if they are bringing up grandchildren. There are so many caveats and exemptions from the help that is available I wonder whether there is anyone actually receiving it.

The real killer is the legislation that has been brought in to prevent immigrants from receiving any state help for several months after they arrive in the uk (are refugees supposed to just starve for 13 weeks - plus the 6 weeks it takes to process the application?) And it is quite a surprise to discover that an under-age British Citizen, a child of British Citizens, who has spent time abroad with one parent, is treated as an immigrant on arrival back in the UK.

A very talented artist!She is now attending college, studying art and hoping to gain some of the GCSE's she missed out on. Live is very full and certainly lively! I'm hoping to get back to some normal working routine shortly. Life at the Mill is never dull!

A very talented artist!She is now attending college, studying art and hoping to gain some of the GCSE's she missed out on. Live is very full and certainly lively! I'm hoping to get back to some normal working routine shortly. Life at the Mill is never dull!

This post is published with the full permission of The Girl! Many thanks.

the Girl herself

the Girl herselfBut I have had to get to grips with the bureaucracy of the Welfare State, which - I have to tell you - is mis-named. Welfare it is not. There are forms for everything - most of them pages long. The telephone helplines are interminable and expensive. The jargon is impenetrable and the Citizen's Advice Bureau totally unable to cope with the demand from tired, frustrated, and often distressed, people. At 16, if you can't live with your parents and they aren't willing to support you, you fall between two categories - you're too old to be taken into care, but you don't automatically get any state support. I'm beginning to realise why so many young people are sleeping rough. There also appears to be no system whereby grandparents can be supported if they are bringing up grandchildren. There are so many caveats and exemptions from the help that is available I wonder whether there is anyone actually receiving it.

The real killer is the legislation that has been brought in to prevent immigrants from receiving any state help for several months after they arrive in the uk (are refugees supposed to just starve for 13 weeks - plus the 6 weeks it takes to process the application?) And it is quite a surprise to discover that an under-age British Citizen, a child of British Citizens, who has spent time abroad with one parent, is treated as an immigrant on arrival back in the UK.

A very talented artist!She is now attending college, studying art and hoping to gain some of the GCSE's she missed out on. Live is very full and certainly lively! I'm hoping to get back to some normal working routine shortly. Life at the Mill is never dull!

A very talented artist!She is now attending college, studying art and hoping to gain some of the GCSE's she missed out on. Live is very full and certainly lively! I'm hoping to get back to some normal working routine shortly. Life at the Mill is never dull!This post is published with the full permission of The Girl! Many thanks.

Published on October 30, 2017 03:57