Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 8

March 7, 2018

Wislawa Szymborska - Absence

I'm sharing women writers this week for World Women's Day. One of my favourites is the Polish Nobel Laureate, Wislawa Szymborska, though I'm only able to read her poetry in translation. Listen to her poem 'Absence' read in Polish with English subtitles. It's so incredibly lyrical and demonstrates how much we lose in the translation. The sound is accompanied by a montage of family photos. Szymborska meditates on what might have happened if her father and her mother had married someone else.

The Poetry Foundation has this to say about Szymborska:

"Well-known in her native Poland, Wislawa Szymborska received international recognition when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1996. In awarding the prize, the Academy praised her “poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality.” Collections of her poems that have been translated into English include People on a Bridge (1990), View with a Grain of Sand: Selected Poems (1995), and Monologue of a Dog (2005).

Readers of Szymborska’s poetry have often noted its wit, irony, and deceptive simplicity. Her poetry examines domestic details and occasions, playing these against the backdrop of history. In the poem “The End and the Beginning,” Szymborska writes, “After every war / someone’s got to tidy up.”

In the New York Times Book Review, Stanislaw Baranczak wrote, “The typical lyrical situation on which a Szymborska poem is founded is the confrontation between the directly stated or implied opinion on an issue and the question that raises doubt about its validity. The opinion not only reflects some widely shared belief or is representative of some widespread mind-set, but also, as a rule, has a certain doctrinaire ring to it: the philosophy behind it is usually speculative, anti-empirical, prone to hasty generalizations, collectivist, dogmatic and intolerant.”

Szymborska lived most of her life in Krakow; she studied Polish literature and society at Jagiellonian University and worked as an editor and columnist. A selection of her reviews was published in English under the title Nonrequired Reading: 2Prose Pieces (2002). She received the Polish PEN Club prize, the Goethe Prize, and the Herder Prize."

The Poetry Foundation has this to say about Szymborska:

"Well-known in her native Poland, Wislawa Szymborska received international recognition when she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1996. In awarding the prize, the Academy praised her “poetry that with ironic precision allows the historical and biological context to come to light in fragments of human reality.” Collections of her poems that have been translated into English include People on a Bridge (1990), View with a Grain of Sand: Selected Poems (1995), and Monologue of a Dog (2005).

Readers of Szymborska’s poetry have often noted its wit, irony, and deceptive simplicity. Her poetry examines domestic details and occasions, playing these against the backdrop of history. In the poem “The End and the Beginning,” Szymborska writes, “After every war / someone’s got to tidy up.”

In the New York Times Book Review, Stanislaw Baranczak wrote, “The typical lyrical situation on which a Szymborska poem is founded is the confrontation between the directly stated or implied opinion on an issue and the question that raises doubt about its validity. The opinion not only reflects some widely shared belief or is representative of some widespread mind-set, but also, as a rule, has a certain doctrinaire ring to it: the philosophy behind it is usually speculative, anti-empirical, prone to hasty generalizations, collectivist, dogmatic and intolerant.”

Szymborska lived most of her life in Krakow; she studied Polish literature and society at Jagiellonian University and worked as an editor and columnist. A selection of her reviews was published in English under the title Nonrequired Reading: 2Prose Pieces (2002). She received the Polish PEN Club prize, the Goethe Prize, and the Herder Prize."

Published on March 07, 2018 09:30

March 6, 2018

Tuesday Poem: The Women by Mary Robinson

She was one of the women

who kissed the bairns

in their box beds, left

the eldest in charge

and went into the storm

She was one of the women

blinded with sleet,

who felt their way

through a roar

louder than steam engines

that swallowed their curses

She was one of the women

hands fish-gutted raw

bones stiff with work,

who dragged the lifeboat

three miles along the storm-bound coast

hauled the twisted sinews of rope

pulled together like oxen

She was one of the women

sleeves rolled to the elbow

bodices sodden with sweat

skirts soaked to their shins,

who tasted brine on their lips

their braids loosened to rats' tails

whipping their salt-taut skin

their clogs skidding on stones

She was one of the women

like the pale girl, her cheeks blood-red

with the rope round her shoulders

raising a hand to halt

when she smelt the seaweed,

who paused for breath

at Briar Dene before the steep

descent to the sea, lest the lifeboat

break free and crush them all

She was one of the women

© Mary Robinson 2015

[Based on the painting "The Women" (1910)by John Charlton in the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, commemorating the women who dragged the Cullercoats lifeboat to Briar Dene in a storm on New Year's Day 1861]

First published in Envoi 17, 5 February 2017

We've been snowbound since last Tuesday, surrounded by snowmageddon in the shape of The Beast from the East - the worst winter weather in many years. But at least we've managed to stay warm and well-fed. Friends in outlying villages have been down to their last tin of beans and some were without electricity huddled round a fire for more than 24 hours. But ferocious storms are a feature of living in the north, particularly the northeast. The painting and the poem above, celebrate an act of heroism during the great storm of 1861 where - unable to launch the Cullercoats lifeboat - a group of women and young men dragged the heavy wooden lifeboat over a steep headland in a raging blizzard so that it could be launched in Briar Dene where the 'Lovely Nelly' had foundered. They managed to rescue everyone on board except the cabin boy.

It's World Women's Day on Thursday, 8th March, so I thought both the painting and the poem were appropriate to celebrate women's achievements. John Charlton's painting celebrated an event that took place when women were still regarded as children under the law, no vote, no right to their own money, no right to their children - higher education and most occupations closed to them. It was painted in 1910 when many of these injustices still existed. We live in a time when the leaders of three major parties in the UK are women - something that would have been unthinkable when I was a child. When I started work there were several professions that you had to give up if you married - a girl I knew was sacked as a nurse (only 3 weeks before the end of her training) when the hospital discovered that she had married before sitting her final exams. In the civil service there were several women who held senior positions although secretly married. Sometimes I think that, as we look ahead at the ground still to be gained, we lose sight of just how far we've come - but at other times achieving equality feels as difficult as hauling several tons of lifeboat over a headland in a storm.

About Mary Robinson: "I grew up in Warwickshire and now live on the Lleyn Peninsula within sight of the Welsh mountains. My work includes my debut poetry collection THE ART OF GARDENING (Flambard) and two signed numbered edition pamphlets - Uist Waulking Song and Out of Time, the latter to accompany a poetry/photographic collaboration exhibited at the Friends' Gallery, Theatre by the Lake in 2015. My poetry has appeared in several magazines and anthologies. I won the Mirehouse Poetry Prize in 2013 and the Second Light Poetry Prize in 2017. For the day job I taught English literature in higher and adult education."Read Mary's Blog here: 'Wild About Poetry'

who kissed the bairns

in their box beds, left

the eldest in charge

and went into the storm

She was one of the women

blinded with sleet,

who felt their way

through a roar

louder than steam engines

that swallowed their curses

She was one of the women

hands fish-gutted raw

bones stiff with work,

who dragged the lifeboat

three miles along the storm-bound coast

hauled the twisted sinews of rope

pulled together like oxen

She was one of the women

sleeves rolled to the elbow

bodices sodden with sweat

skirts soaked to their shins,

who tasted brine on their lips

their braids loosened to rats' tails

whipping their salt-taut skin

their clogs skidding on stones

She was one of the women

like the pale girl, her cheeks blood-red

with the rope round her shoulders

raising a hand to halt

when she smelt the seaweed,

who paused for breath

at Briar Dene before the steep

descent to the sea, lest the lifeboat

break free and crush them all

She was one of the women

© Mary Robinson 2015

[Based on the painting "The Women" (1910)by John Charlton in the Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, commemorating the women who dragged the Cullercoats lifeboat to Briar Dene in a storm on New Year's Day 1861]

First published in Envoi 17, 5 February 2017

We've been snowbound since last Tuesday, surrounded by snowmageddon in the shape of The Beast from the East - the worst winter weather in many years. But at least we've managed to stay warm and well-fed. Friends in outlying villages have been down to their last tin of beans and some were without electricity huddled round a fire for more than 24 hours. But ferocious storms are a feature of living in the north, particularly the northeast. The painting and the poem above, celebrate an act of heroism during the great storm of 1861 where - unable to launch the Cullercoats lifeboat - a group of women and young men dragged the heavy wooden lifeboat over a steep headland in a raging blizzard so that it could be launched in Briar Dene where the 'Lovely Nelly' had foundered. They managed to rescue everyone on board except the cabin boy.

It's World Women's Day on Thursday, 8th March, so I thought both the painting and the poem were appropriate to celebrate women's achievements. John Charlton's painting celebrated an event that took place when women were still regarded as children under the law, no vote, no right to their own money, no right to their children - higher education and most occupations closed to them. It was painted in 1910 when many of these injustices still existed. We live in a time when the leaders of three major parties in the UK are women - something that would have been unthinkable when I was a child. When I started work there were several professions that you had to give up if you married - a girl I knew was sacked as a nurse (only 3 weeks before the end of her training) when the hospital discovered that she had married before sitting her final exams. In the civil service there were several women who held senior positions although secretly married. Sometimes I think that, as we look ahead at the ground still to be gained, we lose sight of just how far we've come - but at other times achieving equality feels as difficult as hauling several tons of lifeboat over a headland in a storm.

About Mary Robinson: "I grew up in Warwickshire and now live on the Lleyn Peninsula within sight of the Welsh mountains. My work includes my debut poetry collection THE ART OF GARDENING (Flambard) and two signed numbered edition pamphlets - Uist Waulking Song and Out of Time, the latter to accompany a poetry/photographic collaboration exhibited at the Friends' Gallery, Theatre by the Lake in 2015. My poetry has appeared in several magazines and anthologies. I won the Mirehouse Poetry Prize in 2013 and the Second Light Poetry Prize in 2017. For the day job I taught English literature in higher and adult education."Read Mary's Blog here: 'Wild About Poetry'

Published on March 06, 2018 09:01

February 27, 2018

James Joyce and Snow 'farther westward, softly falling'. . .

I couldn't sleep last night and got up to stand at the window and watch the snow drifting past in that strange blueish light that snow seems to bring with it. I can't ever watch the snow falling out of the sky without thinking of James Joyce's story 'The Dead' - one of the most perfect short stories ever written. John Huston's film captured the feel of it perfectly and the ending has stayed with me ever since I watched it, just as the last paragraph of the story haunts me. It gives me a little shiver - part sadness, part romance, part response to beauty. 'It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.'

This week the BBC Book at Bedtime is serialising The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which you can find here:

This week the BBC Book at Bedtime is serialising The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, which you can find here:

Published on February 27, 2018 06:11

February 13, 2018

Tuesday Poem: Anne Bradstreet and Elizabeth Barrett Browning on Love

To My Dear and Loving Husband

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were loved by wife, then thee;

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me ye women if you can.

I prize thy love more than whole mines of gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold.

My love is such that rivers cannot quench,

Nor ought but love from thee give recompense.

Thy love is such I can no way repay;

The heavens reward thee manifold, I pray.

Then while we live, in love let’s so persever,

That when we live no more we may live ever.

Anne Bradstreet, 1612 - 1672

How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43)

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1806 - 1861

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? (Sonnet 18)

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to Time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

William Shakespeare, 1564 - 1616

When You Are Old

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

W. B. Yeats, 1865 - 1939

"Oh, think not I am faithful to a vow"

Oh, think not I am faithful to a vow!

Faithless am I save to love's self alone.

Were you not lovely I would leave you now:

After the feet of beauty fly my own.

Were you not still my hunger's rarest food,

And water ever to my wildest thirst,

I would desert you – think not but I would!

And seek another as I sought you first.

But you are mobile as the veering air,

And all your charms more changeful than the tide,

Wherefore to be inconstant is no care:

I have but to continue at your side.

So wanton, light and false, my love, are you,

Edna St Vincent Millay

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were loved by wife, then thee;

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me ye women if you can.

I prize thy love more than whole mines of gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold.

My love is such that rivers cannot quench,

Nor ought but love from thee give recompense.

Thy love is such I can no way repay;

The heavens reward thee manifold, I pray.

Then while we live, in love let’s so persever,

That when we live no more we may live ever.

Anne Bradstreet, 1612 - 1672

How Do I Love Thee? (Sonnet 43)

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day’s

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood’s faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 1806 - 1861

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? (Sonnet 18)

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate.

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date.

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimmed;

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed;

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

Nor shall death brag thou wand’rest in his shade,

When in eternal lines to Time thou grow’st.

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

William Shakespeare, 1564 - 1616

When You Are Old

When you are old and grey and full of sleep,

And nodding by the fire, take down this book,

And slowly read, and dream of the soft look

Your eyes had once, and of their shadows deep;

How many loved your moments of glad grace,

And loved your beauty with love false or true,

But one man loved the pilgrim soul in you,

And loved the sorrows of your changing face;

And bending down beside the glowing bars,

Murmur, a little sadly, how Love fled

And paced upon the mountains overhead

And hid his face amid a crowd of stars.

W. B. Yeats, 1865 - 1939

"Oh, think not I am faithful to a vow"

Oh, think not I am faithful to a vow!

Faithless am I save to love's self alone.

Were you not lovely I would leave you now:

After the feet of beauty fly my own.

Were you not still my hunger's rarest food,

And water ever to my wildest thirst,

I would desert you – think not but I would!

And seek another as I sought you first.

But you are mobile as the veering air,

And all your charms more changeful than the tide,

Wherefore to be inconstant is no care:

I have but to continue at your side.

So wanton, light and false, my love, are you,

Edna St Vincent Millay

Published on February 13, 2018 03:44

February 6, 2018

Tuesday Poem: The Anti-Suffragists by Charlotte Perkins Gilman

Fashionable women in luxurious homes,

With men to feed them, clothe them, pay their bills,

Bow, doff the hat, and fetch the handkerchief;

Hostess or guest, and always so supplied

With graceful deference and courtesy;

Surrounded by their servants, horses, dogs, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Successful women who have won their way

Alone, with strength of their unaided arm,

Or helped by friends, or softly climbing up

By the sweet aid of ‘woman’s influence’;

Successful any way, and caring naught

For any other woman’s unsuccess, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Religious women of the feebler sort, —

Not the religion of a righteous world,

A free, enlightened, upward-reaching world,

But the religion that considers life

As something to back out of! — whose ideal

Is to renounce, submit, and sacrifice,

Counting on being patted on the head

And given a high chair when they get to heaven, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Ignorant women — college-bred sometimes,

But ignorant of life’s realities

And principles of righteous government,

And how the privileges they enjoy

Were won with blood and tears by those before —

Those they condemn, whose ways they now oppose;

Saying, ‘Why not let well enough alone?

Our world is very pleasant as it is,’ —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

And selfish women, — pigs in petticoats, —

Rich, poor, wise, unwise, top or bottom round,

But all sublimely innocent of thought,

And guiltless of ambition, save the one

Deep, voiceless aspiration — to be fed!

These have no use for rights or duties more.

Duties today are more than they can meet,

And law insures their right to clothes and food, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

And, more’s the pity, some good women, too;

Good conscientious women, with ideas;

Who think — or think they think — that woman’s cause

Is best advanced by letting it alone;

That she somehow is not a human thing,

And not to be helped on by human means,

Just added to humanity — an ‘L’ —

A wing, a branch, an extra, not mankind, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

And out of these has come a monstrous thing,

A strange, down-sucking whirlpool of disgrace,

Women uniting against womanhood,

And using that great name to hide their sin!

Vain are their words as that old king’s command

Who set his will against the rising tide.

But who shall measure the historic shame

Of these poor traitors — traitors are they all —

To great Democracy and Womanhood!

© By Charlotte Anna Perkins Gilman

Source: She Wields a Pen: American Women Poets of the Nineteenth Century (University of Iowa Press, 1997)

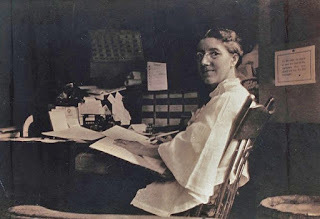

Charlotte Gilman at her deskOn the 100th anniversary of the first chink of light in the fight for women's universal suffrage, it's easy to forget that a lot of the opposition to women's equality was from women themselves - all kinds of women; the privileged and the unprivileged, educated and uneducated. Charlotte Perkins Gilman doesn't mince words, calling them 'pigs in petticoats'.

Charlotte Gilman at her deskOn the 100th anniversary of the first chink of light in the fight for women's universal suffrage, it's easy to forget that a lot of the opposition to women's equality was from women themselves - all kinds of women; the privileged and the unprivileged, educated and uneducated. Charlotte Perkins Gilman doesn't mince words, calling them 'pigs in petticoats'.

Charlotte Gilman (1860 to 1935) was a fervent feminist, author and poet, writing a number of seminal books including The Yellow Wallpaper (informed by her own struggle with depression) and Women and Economics. She committed suicide in 1935, aged seventy five, after discovering that she had breast cancer.

With men to feed them, clothe them, pay their bills,

Bow, doff the hat, and fetch the handkerchief;

Hostess or guest, and always so supplied

With graceful deference and courtesy;

Surrounded by their servants, horses, dogs, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Successful women who have won their way

Alone, with strength of their unaided arm,

Or helped by friends, or softly climbing up

By the sweet aid of ‘woman’s influence’;

Successful any way, and caring naught

For any other woman’s unsuccess, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Religious women of the feebler sort, —

Not the religion of a righteous world,

A free, enlightened, upward-reaching world,

But the religion that considers life

As something to back out of! — whose ideal

Is to renounce, submit, and sacrifice,

Counting on being patted on the head

And given a high chair when they get to heaven, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

Ignorant women — college-bred sometimes,

But ignorant of life’s realities

And principles of righteous government,

And how the privileges they enjoy

Were won with blood and tears by those before —

Those they condemn, whose ways they now oppose;

Saying, ‘Why not let well enough alone?

Our world is very pleasant as it is,’ —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

And selfish women, — pigs in petticoats, —

Rich, poor, wise, unwise, top or bottom round,

But all sublimely innocent of thought,

And guiltless of ambition, save the one

Deep, voiceless aspiration — to be fed!

These have no use for rights or duties more.

Duties today are more than they can meet,

And law insures their right to clothes and food, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

And, more’s the pity, some good women, too;

Good conscientious women, with ideas;

Who think — or think they think — that woman’s cause

Is best advanced by letting it alone;

That she somehow is not a human thing,

And not to be helped on by human means,

Just added to humanity — an ‘L’ —

A wing, a branch, an extra, not mankind, —

These tell us they have all the rights they want.

And out of these has come a monstrous thing,

A strange, down-sucking whirlpool of disgrace,

Women uniting against womanhood,

And using that great name to hide their sin!

Vain are their words as that old king’s command

Who set his will against the rising tide.

But who shall measure the historic shame

Of these poor traitors — traitors are they all —

To great Democracy and Womanhood!

© By Charlotte Anna Perkins Gilman

Source: She Wields a Pen: American Women Poets of the Nineteenth Century (University of Iowa Press, 1997)

Charlotte Gilman at her deskOn the 100th anniversary of the first chink of light in the fight for women's universal suffrage, it's easy to forget that a lot of the opposition to women's equality was from women themselves - all kinds of women; the privileged and the unprivileged, educated and uneducated. Charlotte Perkins Gilman doesn't mince words, calling them 'pigs in petticoats'.

Charlotte Gilman at her deskOn the 100th anniversary of the first chink of light in the fight for women's universal suffrage, it's easy to forget that a lot of the opposition to women's equality was from women themselves - all kinds of women; the privileged and the unprivileged, educated and uneducated. Charlotte Perkins Gilman doesn't mince words, calling them 'pigs in petticoats'.Charlotte Gilman (1860 to 1935) was a fervent feminist, author and poet, writing a number of seminal books including The Yellow Wallpaper (informed by her own struggle with depression) and Women and Economics. She committed suicide in 1935, aged seventy five, after discovering that she had breast cancer.

Published on February 06, 2018 05:48

February 1, 2018

A Weird Week

It's been a weird week here at The Mill. Very little 'air time' - just a jumble of to-ing and fro-ing and a haze of tiredness. Perhaps its the super full moon, but I've not been sleeping well.

Our quest to find independent support for The Girl has expanded into Kafka-esque territory. Apparently the British born, British passport holding children of Brits working abroad are to be considered immigrants. The Girl was summoned to an interview to inquire into her 'right to remain'. There is, of course, no question of it since this is her usual place of residence and all her relatives but one (all British born British passport holders) live in Britain. She is a British Citizen. This is where she belongs. But she still has to prove, apparently, that she's not going to get on a plane to somewhere else tomorrow. The fact that she doesn't have anywhere to go, or the money to do it is immaterial.

Even more bizarre - she's been sent forms asking for her employment history (she's barely 16), for her parents' employment history (she has no contact), for her partner's employment history (she's 16), her mortgage payments (she's 16 remember?), when did your family come to the UK (she's British remember?) and various other irrelevant bits of info (have you been divorced, widowed, separated etc) that any vaguely literate person who read her application form would have known was irrelevant. There's a helpline number on the forms, but it rang and rang and each time we were disconnected before anyone answered. Once we managed to speak to an actual person who promised to ring back but no one ever did. The cut-off date was 2nd Feb (tomorrow) after which the whole process would have to be started again. We hope we have finally sorted it, but none of us will be able to listen to Vivaldi's 4 Seasons ever again.

This 16 year old has 2 adults to help her through this process - what happens to the ones who don't?

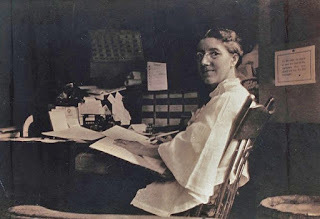

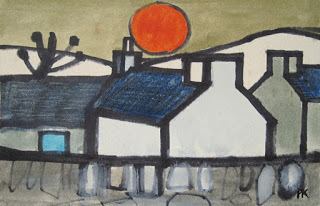

Blue Door, Red Sun

Blue Door, Red Sun

I took the chance presented by one of the DWP visits to look at the Percy Kelly exhibition in Tullie House. It's an amazing retrospective covering a long period of his working life. He was a strange, troubled character, partly self-taught, a protege of the P & O heiress Helen Sutherland, (who was also a patron of the Pitmen Painters in Northumberland). Kelly found it difficult to part with his work and sold few paintings during his lifetime, even though buyers were clamouring to get their hands on his work. He corresponded with people , sending extraordinary painted letters - beautiful water colours illustrating events and places in his life.

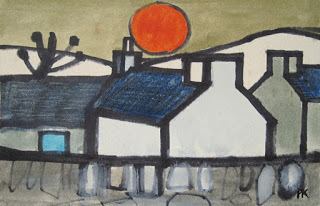

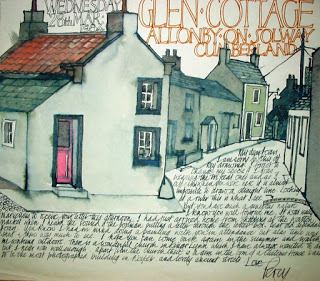

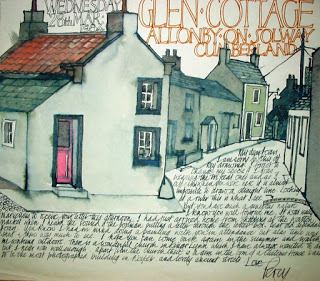

One of the Painted Letters

One of the Painted Letters

Percy ended his life living in Norfolk as a woman called Roberta. Being a woman, he said, freed him from many inhibitions and allowed him to be more aware of sound and colour.

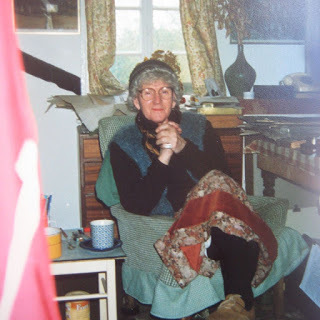

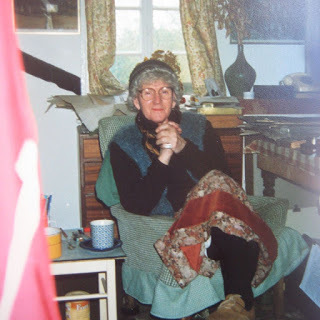

Percy Kelly as Roberta

Percy Kelly as Roberta

Workwise, it's been a busy time - I've had an abstract accepted for a lecture at the Katherine Mansfield Conference at Birkbeck College, London, in June, so now have to get down to the terrifying task of researching and writing it. Then BBC local Radio contacted me and they want me to go in and record a series of pieces about my life story. A sign I must be getting old!

And then on a train to London for the James Street Literary Salon, run by author and writing coach Jacqui Lofthouse and author Alice Jolly. It was a good evening meeting old friends and making new ones. It gets lonely up here in the north - you need to talk to other writers. If only so much of it didn't have to be in London! Jacqui gave a lively talk on motivation and some advice on how to prevent the business side of 'being an author' from taking over the creative side. As most of us had just been wrestling with our tax returns, this really struck a nerve!

Roopa Farooki (and yes, she does look like this!)

Roopa Farooki (and yes, she does look like this!)

Author Roopa Farooki (check out The Good Children) won the multi-tasking award for finishing her 7th novel which looking after 4 children, doing a medical degree (she qualifies as a doctor next year) and lecturing on creative writing at Oxford. Oh, and she does about 50 star jumps when she gets up in the morning. How can I complain of anything ever again?

Our quest to find independent support for The Girl has expanded into Kafka-esque territory. Apparently the British born, British passport holding children of Brits working abroad are to be considered immigrants. The Girl was summoned to an interview to inquire into her 'right to remain'. There is, of course, no question of it since this is her usual place of residence and all her relatives but one (all British born British passport holders) live in Britain. She is a British Citizen. This is where she belongs. But she still has to prove, apparently, that she's not going to get on a plane to somewhere else tomorrow. The fact that she doesn't have anywhere to go, or the money to do it is immaterial.

Even more bizarre - she's been sent forms asking for her employment history (she's barely 16), for her parents' employment history (she has no contact), for her partner's employment history (she's 16), her mortgage payments (she's 16 remember?), when did your family come to the UK (she's British remember?) and various other irrelevant bits of info (have you been divorced, widowed, separated etc) that any vaguely literate person who read her application form would have known was irrelevant. There's a helpline number on the forms, but it rang and rang and each time we were disconnected before anyone answered. Once we managed to speak to an actual person who promised to ring back but no one ever did. The cut-off date was 2nd Feb (tomorrow) after which the whole process would have to be started again. We hope we have finally sorted it, but none of us will be able to listen to Vivaldi's 4 Seasons ever again.

This 16 year old has 2 adults to help her through this process - what happens to the ones who don't?

Blue Door, Red Sun

Blue Door, Red SunI took the chance presented by one of the DWP visits to look at the Percy Kelly exhibition in Tullie House. It's an amazing retrospective covering a long period of his working life. He was a strange, troubled character, partly self-taught, a protege of the P & O heiress Helen Sutherland, (who was also a patron of the Pitmen Painters in Northumberland). Kelly found it difficult to part with his work and sold few paintings during his lifetime, even though buyers were clamouring to get their hands on his work. He corresponded with people , sending extraordinary painted letters - beautiful water colours illustrating events and places in his life.

One of the Painted Letters

One of the Painted LettersPercy ended his life living in Norfolk as a woman called Roberta. Being a woman, he said, freed him from many inhibitions and allowed him to be more aware of sound and colour.

Percy Kelly as Roberta

Percy Kelly as RobertaWorkwise, it's been a busy time - I've had an abstract accepted for a lecture at the Katherine Mansfield Conference at Birkbeck College, London, in June, so now have to get down to the terrifying task of researching and writing it. Then BBC local Radio contacted me and they want me to go in and record a series of pieces about my life story. A sign I must be getting old!

And then on a train to London for the James Street Literary Salon, run by author and writing coach Jacqui Lofthouse and author Alice Jolly. It was a good evening meeting old friends and making new ones. It gets lonely up here in the north - you need to talk to other writers. If only so much of it didn't have to be in London! Jacqui gave a lively talk on motivation and some advice on how to prevent the business side of 'being an author' from taking over the creative side. As most of us had just been wrestling with our tax returns, this really struck a nerve!

Roopa Farooki (and yes, she does look like this!)

Roopa Farooki (and yes, she does look like this!)Author Roopa Farooki (check out The Good Children) won the multi-tasking award for finishing her 7th novel which looking after 4 children, doing a medical degree (she qualifies as a doctor next year) and lecturing on creative writing at Oxford. Oh, and she does about 50 star jumps when she gets up in the morning. How can I complain of anything ever again?

Published on February 01, 2018 11:59

January 23, 2018

Tuesday Poem: How to be a Poet - Jo Bell and Jane Commane

This, the editors stress, is not a How-To manual about writing poetry. Instead

How to be a Poet

is 'a manifesto of sorts. It is an exploration, both practically and creatively, of what it is to write poems, read poems, share poems and publish poetry.'

This handbook grew out of the famous '52' project run by Jo Bell online. The brief was to write a poem a week for a year. The response was phenomenal and some of the resulting poems are gathered together in an anthology called '52'. The original prompts, plus others, are included in the book. But some of the questions that were generated by the project needed answers and Jo Bell and her editor at Nine Arches Press, the poet Jane Commane, began to put together this handbook which is, in a way, a companion to '52'. How to be a Poet is 'a guide to writing well' and to show 'the realities of writing poetry and being a poet in the here and now'.

It is refreshingly blunt. No bullshit in this guide; no false hopes. The life of a poet is hard, and if you want to be a good poet, you're going to have to toughen up your critical skills and launch yourself out into the rocky shoals of the market place. You're going to have to read widely 'for pleasure and curiosity', across genders and genres. We should 'challenge ourselves constantly in our reading'.

Poets, wrote Percy Shelley, 'are the unacknowledged legislators of the world', and there are many other exalted claims for practitioners of the poetic arts. 'Inspiration' is a word that has some poets reaching for the fire extinguisher. Jo Bell also has reservations about this 'dangerous' word: 'It makes writing sound other-worldly and mysterious - as if you have to wait for the butterfly Muse to land on the end of your nose, and jot down the ideas she brings. In fact, writing poetry is a question of observing and interrogating your own experience.'

Jo de-mythologises the role of the poet and quotes William Carlos Williams, ('a poem is a machine made of words') and underlines it by saying: 'Poetry is machinery, not magic and we can understand its workings as well as a car mechanic can understand an engine'. She goes on to demonstrate this with a close reading of Kate Clanchy's marvellous poem Patagonia (which you can read by clicking here).

I've come to this book with a few decades of trying to 'be a poet' behind me, two full collections and two prize-winning pamphlets, but, even for an experienced poet, there is much that is valuable, and not just for leading workshops. A poet must never, never stop learning. There were sections I read shouting 'yes, yes', to the puzzlement of my partner. I particularly enjoyed 'Jo Bell's Big Ruthless List for Poetry Writing', which begins, 'Get rid of cliché. All of it', and ends '"Good enough" isn't good enough. Keep editing until it is as good as it can be, has something to say and says it your way'. Much more helpful than Ezra Pound's 'murder your darlings'!

There are sections on beginning, on ending, on performing, the realities of trying to earn money from poetry. It covers submitting your work to editors, particularly how to catch an editor's eye, and what not to do if you want to get your poem published. Jane Commane lists several absolute no's. You should always read the submission guide carefully and follow it faithfully. No handwritten mss endorsed by your Aunty, no photographs, requests for feedback, a copy of your self-published pamphlet, and definitely no simultaneous submissions. If a poem is good enough to be accepted by one magazine then it's quite likely to be accepted by another and you've wasted an editor's time when you have to withdraw it. The editor is unlikely to forget. Jo Bell has a tried and tested, foolproof method of sending out poems to avoid the embarrassment of the simultaneous submission - a spreadsheet which is included in the book.

There's quite a lot on drafting and editing 'Words are a blunt tool with which to tackle our lived experience, but they are what we have'. Jo bravely includes the first draft of her poem Mallaig alongside the final, published version. There are also sections written by guest poets such as Mona Arshi and Robert Peake. Joelle Taylor has an interesting piece on 'Interrogating the Self'. 'If your poem only works for you . . . then it's probably something you should keep for yourself'. Catharsis should never be a justification.

This is a much-needed refreshing look at the business of 'being a poet' and everyone who is or who aspires to be, should read it. Apart from all the other stuff in the book, it helps you to sustain self-belief and gives you permission to write and publish your little machines made of words. It's easy to lose hope in the poetry wilderness. How to be a Poet is the perfect antidote.

How to be a Poet, ed. Jo Bell & Jane Commane, is published by Nine Arches Press and costs £14.99

52: Write a Poem a Week is available on this link for £14.99

This handbook grew out of the famous '52' project run by Jo Bell online. The brief was to write a poem a week for a year. The response was phenomenal and some of the resulting poems are gathered together in an anthology called '52'. The original prompts, plus others, are included in the book. But some of the questions that were generated by the project needed answers and Jo Bell and her editor at Nine Arches Press, the poet Jane Commane, began to put together this handbook which is, in a way, a companion to '52'. How to be a Poet is 'a guide to writing well' and to show 'the realities of writing poetry and being a poet in the here and now'.

It is refreshingly blunt. No bullshit in this guide; no false hopes. The life of a poet is hard, and if you want to be a good poet, you're going to have to toughen up your critical skills and launch yourself out into the rocky shoals of the market place. You're going to have to read widely 'for pleasure and curiosity', across genders and genres. We should 'challenge ourselves constantly in our reading'.

Poets, wrote Percy Shelley, 'are the unacknowledged legislators of the world', and there are many other exalted claims for practitioners of the poetic arts. 'Inspiration' is a word that has some poets reaching for the fire extinguisher. Jo Bell also has reservations about this 'dangerous' word: 'It makes writing sound other-worldly and mysterious - as if you have to wait for the butterfly Muse to land on the end of your nose, and jot down the ideas she brings. In fact, writing poetry is a question of observing and interrogating your own experience.'

Jo de-mythologises the role of the poet and quotes William Carlos Williams, ('a poem is a machine made of words') and underlines it by saying: 'Poetry is machinery, not magic and we can understand its workings as well as a car mechanic can understand an engine'. She goes on to demonstrate this with a close reading of Kate Clanchy's marvellous poem Patagonia (which you can read by clicking here).

I've come to this book with a few decades of trying to 'be a poet' behind me, two full collections and two prize-winning pamphlets, but, even for an experienced poet, there is much that is valuable, and not just for leading workshops. A poet must never, never stop learning. There were sections I read shouting 'yes, yes', to the puzzlement of my partner. I particularly enjoyed 'Jo Bell's Big Ruthless List for Poetry Writing', which begins, 'Get rid of cliché. All of it', and ends '"Good enough" isn't good enough. Keep editing until it is as good as it can be, has something to say and says it your way'. Much more helpful than Ezra Pound's 'murder your darlings'!

There are sections on beginning, on ending, on performing, the realities of trying to earn money from poetry. It covers submitting your work to editors, particularly how to catch an editor's eye, and what not to do if you want to get your poem published. Jane Commane lists several absolute no's. You should always read the submission guide carefully and follow it faithfully. No handwritten mss endorsed by your Aunty, no photographs, requests for feedback, a copy of your self-published pamphlet, and definitely no simultaneous submissions. If a poem is good enough to be accepted by one magazine then it's quite likely to be accepted by another and you've wasted an editor's time when you have to withdraw it. The editor is unlikely to forget. Jo Bell has a tried and tested, foolproof method of sending out poems to avoid the embarrassment of the simultaneous submission - a spreadsheet which is included in the book.

There's quite a lot on drafting and editing 'Words are a blunt tool with which to tackle our lived experience, but they are what we have'. Jo bravely includes the first draft of her poem Mallaig alongside the final, published version. There are also sections written by guest poets such as Mona Arshi and Robert Peake. Joelle Taylor has an interesting piece on 'Interrogating the Self'. 'If your poem only works for you . . . then it's probably something you should keep for yourself'. Catharsis should never be a justification.

This is a much-needed refreshing look at the business of 'being a poet' and everyone who is or who aspires to be, should read it. Apart from all the other stuff in the book, it helps you to sustain self-belief and gives you permission to write and publish your little machines made of words. It's easy to lose hope in the poetry wilderness. How to be a Poet is the perfect antidote.

How to be a Poet, ed. Jo Bell & Jane Commane, is published by Nine Arches Press and costs £14.99

52: Write a Poem a Week is available on this link for £14.99

Published on January 23, 2018 05:13

January 16, 2018

Tuesday Poem: P.J. Kavanagh - And Light Fading

It's like a de Chirico drawing. The sun going,

A boy on a big grey horse with his bare ankles showing,

A little boy below exclaiming at the hunter's huge feet:

Eyes of saffron heifers reflecting yellow light,

Anxious, standing back from the yard gate:

Garish among the ochre fallows

And high bare field with scooped lavender shadows

A green surprising triangle of winter wheat.

The lane winds up and long. Winter hedgerows

Burn, lemon-green and coral, trap a black bag or sack that blows

Sometimes in a wind above the lane.

Boys and big grey horse and fields and man:

Black plastic like a broken bird, flapping, cracking:

Coloured lane climbing away, and turning, narrowing, and light fading.

Copyright P.J. Kavanagh

Collected Poems, Carcanet Press 1995

It could be a picture of an Irish landscape - and indeed there is an Irish poet called Patrick Kavanagh and an Irish film called The Fading Light directed by another Irishman called Kavanagh.

P.J. Kavanagh was English, but of Irish origin. He died in 2015. He was best known to many for his appearance in Father Ted and his moving memoir Perfect Stranger. I love the economy of his poems, where every word counts. I don't think you need to know the de Chirico drawing to understand this sonnet. The words are laid on the paper like paint. There's also that sense of something ominous just out of sight that de Chirico conveys, using space and light and shadow to suggest threat.

A boy on a big grey horse with his bare ankles showing,

A little boy below exclaiming at the hunter's huge feet:

Eyes of saffron heifers reflecting yellow light,

Anxious, standing back from the yard gate:

Garish among the ochre fallows

And high bare field with scooped lavender shadows

A green surprising triangle of winter wheat.

The lane winds up and long. Winter hedgerows

Burn, lemon-green and coral, trap a black bag or sack that blows

Sometimes in a wind above the lane.

Boys and big grey horse and fields and man:

Black plastic like a broken bird, flapping, cracking:

Coloured lane climbing away, and turning, narrowing, and light fading.

Copyright P.J. Kavanagh

Collected Poems, Carcanet Press 1995

It could be a picture of an Irish landscape - and indeed there is an Irish poet called Patrick Kavanagh and an Irish film called The Fading Light directed by another Irishman called Kavanagh.

P.J. Kavanagh was English, but of Irish origin. He died in 2015. He was best known to many for his appearance in Father Ted and his moving memoir Perfect Stranger. I love the economy of his poems, where every word counts. I don't think you need to know the de Chirico drawing to understand this sonnet. The words are laid on the paper like paint. There's also that sense of something ominous just out of sight that de Chirico conveys, using space and light and shadow to suggest threat.

Published on January 16, 2018 05:16

January 12, 2018

Katherine Mansfield: 'I want to be a child of the sun'

In February 1922, Katherine Mansfield wrote in her notebook 'Short stories seem unreal and not worth doing. I don't want to write; I want to Live.' This was a quiet moment of despair for someone who had once written, 'I am a writer first and a woman after'. Katherine was aware of the rapid advance of her tuberculosis, which had invaded every part of her body, and was almost always in pain. She had less than a year to live.

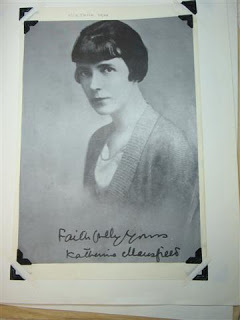

An emaciated Katherine Mansfield - one of the last photosThe knowledge of her imminent death pervades everything she wrote in the last years of her life. It includes some of her most profound and celebrated stories. At The Bay contains a passage where the young Kezia is on the beach with her grandmother.

An emaciated Katherine Mansfield - one of the last photosThe knowledge of her imminent death pervades everything she wrote in the last years of her life. It includes some of her most profound and celebrated stories. At The Bay contains a passage where the young Kezia is on the beach with her grandmother.

'Does everybody have to die?' asked Kezia.

'Everybody!'

'Me?' Kezia sounded fearfully incredulous.

'Some day, my darling.'

'But, Grandma,' Kezia waved her left leg and waggled the toes. They felt sandy. 'What if I just won't?'

The old woman sighed again and drew a long thread from the ball. 'We're not asked, Kezia,' she said sadly. 'It happens to all of us sooner of later.'

Her journals and letters during those last two years contain some of her best writing and there are some heartbreaking passages. Katherine was young and gifted, and she wanted to live a full and vibrant life. Instead she had to spend most of her time in bed and cope with the knowledge that her husband was having a rather clumsy affair with her best friend. She wrote in her notebook about her own hopes - not death and darkness and the paraphernalia of sickness: she wants to feel that she is walking toward life and light. While she knew perfectly well that she was dying, she could still write of her hopes and dreams - the little cottage in the country with a garden, animals, books, music . . .

'... the power to live a full, adult, living breathing life in close contact [with] what I love - the earth and the wonders thereof, the sea, the sun. All that we mean when we speak of the external world . . . I want, by understanding myself, to understand others. I want to be all that I am capable of becoming so that I may be - (and here I have stopped and waited and waited and it's no good - there's only one phrase that will do) a child of the sun.'

Her personal turmoil led her to the teachings of PD Ouspensky and eventually to Gurdjieff. Katherine looked into the abyss of human emotion. Her suffering set her apart from people living ordinary lives and gave her a very special insight into the nature of life lived in the constant shadow of death. After she took refuge with Gurdjieff at Fontainebleau, she wrote to Ouspensky:

'You know that I have long since looked upon all of us without exception as people who have suffered shipwreck and been cast upon an uninhabited island, but who do not yet know of it. But these people here know it. The others, there in life, still think that a steamer will come for them and that everything will go on in the old way. These already know that there will be no more of the old way. I am so glad that I can be here.'

Katherine Mansfield died at Fontainebleau near Paris, on January 9th, 1923 a few months after her 34th birthday. She was buried in a small cemetery at Avon.

Kathleen Jones ' Katherine Mansfield: The Storyteller' (Penguin NZ and Edinburgh University Press)

Gerri Kimber ' Katherine Mansfield: The Early Years' (Edinburgh University Press)

Redmer Yska A Strange Beautiful Excitement (Otago University Press)

An emaciated Katherine Mansfield - one of the last photosThe knowledge of her imminent death pervades everything she wrote in the last years of her life. It includes some of her most profound and celebrated stories. At The Bay contains a passage where the young Kezia is on the beach with her grandmother.

An emaciated Katherine Mansfield - one of the last photosThe knowledge of her imminent death pervades everything she wrote in the last years of her life. It includes some of her most profound and celebrated stories. At The Bay contains a passage where the young Kezia is on the beach with her grandmother.'Does everybody have to die?' asked Kezia.

'Everybody!'

'Me?' Kezia sounded fearfully incredulous.

'Some day, my darling.'

'But, Grandma,' Kezia waved her left leg and waggled the toes. They felt sandy. 'What if I just won't?'

The old woman sighed again and drew a long thread from the ball. 'We're not asked, Kezia,' she said sadly. 'It happens to all of us sooner of later.'

Her journals and letters during those last two years contain some of her best writing and there are some heartbreaking passages. Katherine was young and gifted, and she wanted to live a full and vibrant life. Instead she had to spend most of her time in bed and cope with the knowledge that her husband was having a rather clumsy affair with her best friend. She wrote in her notebook about her own hopes - not death and darkness and the paraphernalia of sickness: she wants to feel that she is walking toward life and light. While she knew perfectly well that she was dying, she could still write of her hopes and dreams - the little cottage in the country with a garden, animals, books, music . . .

'... the power to live a full, adult, living breathing life in close contact [with] what I love - the earth and the wonders thereof, the sea, the sun. All that we mean when we speak of the external world . . . I want, by understanding myself, to understand others. I want to be all that I am capable of becoming so that I may be - (and here I have stopped and waited and waited and it's no good - there's only one phrase that will do) a child of the sun.'

Her personal turmoil led her to the teachings of PD Ouspensky and eventually to Gurdjieff. Katherine looked into the abyss of human emotion. Her suffering set her apart from people living ordinary lives and gave her a very special insight into the nature of life lived in the constant shadow of death. After she took refuge with Gurdjieff at Fontainebleau, she wrote to Ouspensky:

'You know that I have long since looked upon all of us without exception as people who have suffered shipwreck and been cast upon an uninhabited island, but who do not yet know of it. But these people here know it. The others, there in life, still think that a steamer will come for them and that everything will go on in the old way. These already know that there will be no more of the old way. I am so glad that I can be here.'

Katherine Mansfield died at Fontainebleau near Paris, on January 9th, 1923 a few months after her 34th birthday. She was buried in a small cemetery at Avon.

Kathleen Jones ' Katherine Mansfield: The Storyteller' (Penguin NZ and Edinburgh University Press)

Gerri Kimber ' Katherine Mansfield: The Early Years' (Edinburgh University Press)

Redmer Yska A Strange Beautiful Excitement (Otago University Press)

Published on January 12, 2018 06:25

January 8, 2018

Tuesday Poem: Silecroft Shore by Norman Nicholson

Yesterday, the 8th of January, was Norman Nicholson's birthday. He was born in 1914 in a small dwelling in Millom, Cumbria, a seaside mining town in the south of the Lake District. It was not a pretty place and there was little money. His father was a tailor's apprentice and his mother a dressmaker. His infancy was blighted by the fact that a previous baby, Harold, had died of enteritis when only a few months old. The winter was bitter, and Norman was regarded as a sickly baby. His over-protective parents wrapped and lagged him against the weather like water pipes against the frost, he later said. It had a profound effect on him. To make matters worse his mother died in the 1918 flu epidemic, Norman contracted TB at 16 and spent 2 years in a sanatorium. His loving father became even more protective of his only child.

Solitary, physically restricted in what he could do, Norman spent a lot of time wandering in the landscape, observing and recording. A precocious poet, much of his poetry focuses on the landscape around Millom, where he lived in the same house, No 14 George Street, until he died. Silecroft Shore was only one of the wild and beautiful places that he identified with.

A new book about Topographical writing, Coastal Works: Cultures of the Atlantic Edge, published by OUP, devotes a whole chapter to Norman's work. 'At the Dying Atlantic's Edge' is written by Andrew Gibson. Unfortunately, like most academic publications, you need to take out a mortgage to afford it. Even the Kindle edition costs £46.00!

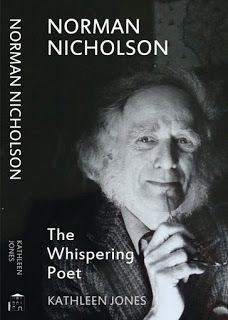

The Whispering Poet, the Book Mill, 2014

The Norman Nicholson Society is currently trying to preserve Norman's home as a museum. To find out more about the poet and the house, please click on the link. You can also find them on Facebook, and on Twitter as @NNicholsonPoet

Published on January 08, 2018 16:30