Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 11

September 1, 2017

After the Floods - Wasp-mageddon

We have a plague of wasps. There is, clearly, a wasp nest under the slates at the apex of the roof but - as it is more than 40 feet above the ground it is beyond the reach of anything but a fire brigade ladder. I didn't think it was a good idea for Neil to climb out of the skylight and totter across the slates. So the wasps keep crawling out of a crack in the ceiling, buzzing around for a few moments and then dying in a spectacular paroxysm on the carpet.

This morning's casualtiesWhy they are emerging from the nest to die immediately we don't know. There are very few insects around at the moment and it's a puzzle. Here on the riverbank we are always pestered by mosquitoes and midges, particularly in the summer. But this year we have sat out in the garden, even on the weir, without a single citronella candle and no need for any kind of repellent. It was the same thing walking up on the moor - no cloud of flies circling our heads; no midges to wave away. I think this is part of the answer to why we've had so few birds in the garden this year.

This morning's casualtiesWhy they are emerging from the nest to die immediately we don't know. There are very few insects around at the moment and it's a puzzle. Here on the riverbank we are always pestered by mosquitoes and midges, particularly in the summer. But this year we have sat out in the garden, even on the weir, without a single citronella candle and no need for any kind of repellent. It was the same thing walking up on the moor - no cloud of flies circling our heads; no midges to wave away. I think this is part of the answer to why we've had so few birds in the garden this year.

A recent report from Yale University called ' What's Causing the Sharp Decline in Insect Life and Why It Matters' blames agricultural pesticides (which are widely used around here) for the dramatic fall in insect populations - including bees. The plight of the bee gets a lot of publicity, but other insects are just as important in the eco-system and we should be worried. To quote the report, a study done in Germany by Martin Sorg, an entomologist from the Krefelt Entomological Association, found that:-

the average biomass of insects caught between May and October has steadily decreased from 1.6 kilograms (3.5 pounds) per trap in 1989 to just 300 grams (10.6 ounces) in 2014.

[Sorg commented that ] “The decline is dramatic and depressing and it affects all kinds of insects, including butterflies, wild bees, and hoverflies,”. . .

Flood damage in Donegal - hardly reported at all in UK media.

Flood damage in Donegal - hardly reported at all in UK media.

When not avoiding the wasps (I'm allergic!) I've been watching the plight of flood victims in Asia, Houston and Donegal. Friends and family in Houston have all been affected to some degree, varying from not being able to go anywhere to having four feet of water in a first floor flat. A niece in Donegal, who lives alone with two small children, had 41 inches of raging river torrent through her bungalow in the middle of the night. The immediacy of social media means that you are sharing their ordeal, moment by moment without being able to do much. Watching people wading through muddy water brought back my own experiences of Storm Desmond vividly and I've had nightmares about it.

Repair work is still ongoing almost two years laterFor those hit by the floods their journey has just begun. Many of those just glad to be alive in Texas don't realise how long it will take to restore 'normality'. In Asia, normality may never return. Here in Cumbria, almost two years on, some people are still not back in their houses, many of which are boarded up and may be abandoned as uninhabitable. We have bailey bridges, temporary road repairs and broken promises from central government to fund the costs. Only a fraction of the promised billions has been paid.

Repair work is still ongoing almost two years laterFor those hit by the floods their journey has just begun. Many of those just glad to be alive in Texas don't realise how long it will take to restore 'normality'. In Asia, normality may never return. Here in Cumbria, almost two years on, some people are still not back in their houses, many of which are boarded up and may be abandoned as uninhabitable. We have bailey bridges, temporary road repairs and broken promises from central government to fund the costs. Only a fraction of the promised billions has been paid.

Here at the Mill work has begun on our footbridge, to shore up the legs and try to prevent the erosion of the bank around them that happened during Storm Desmond when the bridge was totally submerged. It will be two years at the beginning of December. Downstairs in the Mill we still haven't finished the repair work, but the building is almost dried out. We can begin to paint the walls. I have my fingers crossed for winter 2018, but fear a wet summer may turn into a wet winter. We will just have to live with it.

This morning's casualtiesWhy they are emerging from the nest to die immediately we don't know. There are very few insects around at the moment and it's a puzzle. Here on the riverbank we are always pestered by mosquitoes and midges, particularly in the summer. But this year we have sat out in the garden, even on the weir, without a single citronella candle and no need for any kind of repellent. It was the same thing walking up on the moor - no cloud of flies circling our heads; no midges to wave away. I think this is part of the answer to why we've had so few birds in the garden this year.

This morning's casualtiesWhy they are emerging from the nest to die immediately we don't know. There are very few insects around at the moment and it's a puzzle. Here on the riverbank we are always pestered by mosquitoes and midges, particularly in the summer. But this year we have sat out in the garden, even on the weir, without a single citronella candle and no need for any kind of repellent. It was the same thing walking up on the moor - no cloud of flies circling our heads; no midges to wave away. I think this is part of the answer to why we've had so few birds in the garden this year. A recent report from Yale University called ' What's Causing the Sharp Decline in Insect Life and Why It Matters' blames agricultural pesticides (which are widely used around here) for the dramatic fall in insect populations - including bees. The plight of the bee gets a lot of publicity, but other insects are just as important in the eco-system and we should be worried. To quote the report, a study done in Germany by Martin Sorg, an entomologist from the Krefelt Entomological Association, found that:-

the average biomass of insects caught between May and October has steadily decreased from 1.6 kilograms (3.5 pounds) per trap in 1989 to just 300 grams (10.6 ounces) in 2014.

[Sorg commented that ] “The decline is dramatic and depressing and it affects all kinds of insects, including butterflies, wild bees, and hoverflies,”. . .

Flood damage in Donegal - hardly reported at all in UK media.

Flood damage in Donegal - hardly reported at all in UK media.

When not avoiding the wasps (I'm allergic!) I've been watching the plight of flood victims in Asia, Houston and Donegal. Friends and family in Houston have all been affected to some degree, varying from not being able to go anywhere to having four feet of water in a first floor flat. A niece in Donegal, who lives alone with two small children, had 41 inches of raging river torrent through her bungalow in the middle of the night. The immediacy of social media means that you are sharing their ordeal, moment by moment without being able to do much. Watching people wading through muddy water brought back my own experiences of Storm Desmond vividly and I've had nightmares about it.

Repair work is still ongoing almost two years laterFor those hit by the floods their journey has just begun. Many of those just glad to be alive in Texas don't realise how long it will take to restore 'normality'. In Asia, normality may never return. Here in Cumbria, almost two years on, some people are still not back in their houses, many of which are boarded up and may be abandoned as uninhabitable. We have bailey bridges, temporary road repairs and broken promises from central government to fund the costs. Only a fraction of the promised billions has been paid.

Repair work is still ongoing almost two years laterFor those hit by the floods their journey has just begun. Many of those just glad to be alive in Texas don't realise how long it will take to restore 'normality'. In Asia, normality may never return. Here in Cumbria, almost two years on, some people are still not back in their houses, many of which are boarded up and may be abandoned as uninhabitable. We have bailey bridges, temporary road repairs and broken promises from central government to fund the costs. Only a fraction of the promised billions has been paid.

Here at the Mill work has begun on our footbridge, to shore up the legs and try to prevent the erosion of the bank around them that happened during Storm Desmond when the bridge was totally submerged. It will be two years at the beginning of December. Downstairs in the Mill we still haven't finished the repair work, but the building is almost dried out. We can begin to paint the walls. I have my fingers crossed for winter 2018, but fear a wet summer may turn into a wet winter. We will just have to live with it.

Published on September 01, 2017 05:12

August 22, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Alice Oswald Falling Awake

FOX

I heard a cough

as if a thief was there

outside my sleep

a sharp intake of air

a fox in her fox-fur

stepping across

the grass in her black gloves

barked at my house

just so abrupt and odd

the way she went

hungrily asking

in the heart's thick accent

in such serious sleepless

trespass she came

a woman with a man's voice

but no name

as if to say: it's midnight

and my life

is laid beneath my children

like gold leaf

© Alice Oswald

Falling Awake, Cape Poetry, London, 2016

What to say about Alice Oswald and her latest collection 'Falling Awake', shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize and winner of the Costa Poetry Award? I've always had an ambivalent attitude to her poetry; not always liking it on the page, but being utterly spell-bound when I hear her read. I think this is because of the oral quality of much of the poetry - thick with repetitions and aural devices. Lovely to listen to, but not so thrilling on the page. Yet, there are poems of hers I would have given anything to have written myself - lines that knock me out, like 'hungrily asking/in the heart's thick accent'. She has the fox pinned, in this poem 'in her black gloves' outside the window. But I'm troubled by the last verse - gold leaf is laid over things, not under them. Is there some hidden significance I'm missing there? Or is this simply reason overlooked for rhetorical effect?

One of the other poems I love in this collection is 'Looking Down', which begins:

Clouds: I can watch their films in puddles

passionate and slow without obligations of shape or stillness

I can stand with wilted neck and look

directly into the drowned corpse of a cloud

it is cold-blooded down there

precisely outlined as if under a spell

and it narrows to a weighted point which

throws back darkness

oh yes there is a trembling rod that hangs my head above puddles

and the clouds like trapped smoke wander under me

and the sun lies discarded on the tarmac . . .

When I read this, I'm there, looking down at the sky reflected in a puddle and the words are so perfect and the shape of the poem so cloud-like, I'm captivated. It ends with 'a crow on a glass lens' which 'slides through the earth'.

I'm less fond of the long poem 'Tythonus' which occupies quite a lot of space in this collection. I heard it read on the radio which it first came out (it was written for radio) and it bored me. I feel rather ashamed of this admission, but - since I've just had a big birthday - I might as well be honest.

Most oral poetry, written for performance, is political. Oswald's poetry is not. I am bothered by its classical preoccupations, by its backward-looking habit. The glimpses of the natural world are exquisite, but I feel that something is missing when I read them. 'Falling Awake' is a fantastic read, but it leaves me just as ambivalent as I was before! There is much to love and much that leaves me cold. But there is also poetry that is spectacular. And it is always eloquent.

I heard a cough

as if a thief was there

outside my sleep

a sharp intake of air

a fox in her fox-fur

stepping across

the grass in her black gloves

barked at my house

just so abrupt and odd

the way she went

hungrily asking

in the heart's thick accent

in such serious sleepless

trespass she came

a woman with a man's voice

but no name

as if to say: it's midnight

and my life

is laid beneath my children

like gold leaf

© Alice Oswald

Falling Awake, Cape Poetry, London, 2016

What to say about Alice Oswald and her latest collection 'Falling Awake', shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize and winner of the Costa Poetry Award? I've always had an ambivalent attitude to her poetry; not always liking it on the page, but being utterly spell-bound when I hear her read. I think this is because of the oral quality of much of the poetry - thick with repetitions and aural devices. Lovely to listen to, but not so thrilling on the page. Yet, there are poems of hers I would have given anything to have written myself - lines that knock me out, like 'hungrily asking/in the heart's thick accent'. She has the fox pinned, in this poem 'in her black gloves' outside the window. But I'm troubled by the last verse - gold leaf is laid over things, not under them. Is there some hidden significance I'm missing there? Or is this simply reason overlooked for rhetorical effect?

One of the other poems I love in this collection is 'Looking Down', which begins:

Clouds: I can watch their films in puddles

passionate and slow without obligations of shape or stillness

I can stand with wilted neck and look

directly into the drowned corpse of a cloud

it is cold-blooded down there

precisely outlined as if under a spell

and it narrows to a weighted point which

throws back darkness

oh yes there is a trembling rod that hangs my head above puddles

and the clouds like trapped smoke wander under me

and the sun lies discarded on the tarmac . . .

When I read this, I'm there, looking down at the sky reflected in a puddle and the words are so perfect and the shape of the poem so cloud-like, I'm captivated. It ends with 'a crow on a glass lens' which 'slides through the earth'.

I'm less fond of the long poem 'Tythonus' which occupies quite a lot of space in this collection. I heard it read on the radio which it first came out (it was written for radio) and it bored me. I feel rather ashamed of this admission, but - since I've just had a big birthday - I might as well be honest.

Most oral poetry, written for performance, is political. Oswald's poetry is not. I am bothered by its classical preoccupations, by its backward-looking habit. The glimpses of the natural world are exquisite, but I feel that something is missing when I read them. 'Falling Awake' is a fantastic read, but it leaves me just as ambivalent as I was before! There is much to love and much that leaves me cold. But there is also poetry that is spectacular. And it is always eloquent.

Published on August 22, 2017 08:25

July 28, 2017

What is happening to the birds?

The Mill on the other side of the weirI live next to a big river in a fairly wild environment with trees and wild flowers and water meadows on either side. We live with herons, currently two in residence about 20 yards apart, ducks, geese, dippers, wagtails, tree creepers, thrushes, blackbirds, blue tits, wrens, wood pigeons and innumerable other smaller birds.

The Mill on the other side of the weirI live next to a big river in a fairly wild environment with trees and wild flowers and water meadows on either side. We live with herons, currently two in residence about 20 yards apart, ducks, geese, dippers, wagtails, tree creepers, thrushes, blackbirds, blue tits, wrens, wood pigeons and innumerable other smaller birds.  The heron showing off on the river bankThe old Mill offers a variety of habitats in its crumbling stonework, and the ivy cladding on the cliff behind it harbours nesting birds including the ducks. I once saw a mother duck leading her newly-hatched brood in a 15 foot tumble through the ivy to the river bank!

The heron showing off on the river bankThe old Mill offers a variety of habitats in its crumbling stonework, and the ivy cladding on the cliff behind it harbours nesting birds including the ducks. I once saw a mother duck leading her newly-hatched brood in a 15 foot tumble through the ivy to the river bank!At this time of year the river is usually crowded with ducklings in all stages of development and the wilderness that is my garden rustling with young birds still being fed by their parents. But not this year.

One of last year's broods.We have had no ducklings. None. The ducks usually produce more than a dozen or so each, starting out as small feathered flotillas on the weir and gradually reducing as predators take their toll - ducks are terrible mothers! But generally three or four per duck survive to grow and thrive. Not this year.

One of last year's broods.We have had no ducklings. None. The ducks usually produce more than a dozen or so each, starting out as small feathered flotillas on the weir and gradually reducing as predators take their toll - ducks are terrible mothers! But generally three or four per duck survive to grow and thrive. Not this year.We have a pair of swans on the weir as permanent residents and last year they raised five cygnets. This year they reappeared alone.

Last year's swans with cygnetsSummer barbecues always have a backdrop of screaming swifts, dive bombing the water for the clouds of insects that accumulate above the surface of the river. We have some swifts, but they were late to arrive this year and there aren't so many of them. Fewer swallows too - my neighbour has had swallows nesting in the porch for as long as anyone can remember. But this year they didn't return.

Last year's swans with cygnetsSummer barbecues always have a backdrop of screaming swifts, dive bombing the water for the clouds of insects that accumulate above the surface of the river. We have some swifts, but they were late to arrive this year and there aren't so many of them. Fewer swallows too - my neighbour has had swallows nesting in the porch for as long as anyone can remember. But this year they didn't return. Last year's geeseAll this is very worrying. We had a mild winter and a very warm and hospitable spring. Summer is a bit cool and damp, but no more than usual. But I notice in the garden we have less insects than we normally have and wonder why? Fewer bees and no midges or mosquitoes yet, which is strange. River levels have been very low because of the lack of winter rain, but nothing desperate. Perhaps the dearth of baby birds is to do with an increase in predators - we have a lot of crows, a pair of peregrines and some buzzards.

Last year's geeseAll this is very worrying. We had a mild winter and a very warm and hospitable spring. Summer is a bit cool and damp, but no more than usual. But I notice in the garden we have less insects than we normally have and wonder why? Fewer bees and no midges or mosquitoes yet, which is strange. River levels have been very low because of the lack of winter rain, but nothing desperate. Perhaps the dearth of baby birds is to do with an increase in predators - we have a lot of crows, a pair of peregrines and some buzzards. My wild and overgrown garden - usually a haven for wildlife.Something has changed. Is this a one year catastrophe, local to us? or is this a symptom of something bigger? I wish I knew.

My wild and overgrown garden - usually a haven for wildlife.Something has changed. Is this a one year catastrophe, local to us? or is this a symptom of something bigger? I wish I knew.I'm now on summer holidays - officially! So I won't be blogging as frequently. I'm going to enjoy a lazy August - here's wishing happy summer holidays to you all!

Published on July 28, 2017 06:32

July 17, 2017

On trying to live an ethical life

Like most people I try to lead an ethical life, but it’s not easy. Every aspect of your life has an impact on other people or on the planet. And, as a writer, used to analysing and reflecting, you can’t shut yourself in a dark cupboard and hope all the difficult issues go away.

The state of the planet is the one concerning me most at the moment. Last week I went to a showing of the film A Plastic Ocean, made by a very distinguished team who worked on David Attenborough’s Blue Planet series, and it's narrated by journalist Craig Leeson who started out looking for the rare and elusive Blue Whale in order to film a documentary. What happened next was horrific. The diving team surfaced under a curtain of plastic pollution, much of which was going into the whales’ stomachs. As their search for the whale went on, they found more and more plastic accumulating in even the remotest parts of the ocean.

The plastic pollution of the ocean has intensified over the last decade to numbers that make your hair stand on end. Millions of tons of plastic waste go into the ocean every WEEK. And most of it comes from us and our addiction to single-use plastic. Supermarket carrier bags, drinking straws, fast-food trays, freezer bags, take-away cutlery, bottles of water . . . on and on and on. Some single-use plastic has an active life of only 10 minutes. The film showed the consequences for wild life and I have to say that it was upsetting. Endangered species are dying of starvation because they have stomachs full of plastic. Albatrosses are feeding plastic to their chicks, turtles are mistaking plastic bags for jellyfish, whales are sieving it out of the water instead of krill.

I have been trying not to buy plastic carrier bags from supermarkets - but I’m not perfect and there is always the time I forget to bring any with me. I try to recycle, but it’s not easy around here because the council don’t collect and it all has to be driven to the dump. I carry my own water bottle, but sometimes on a train I end up buying water in a bottle because there’s no way to get a clean refill.

It’s clear that we have to do something before the ocean becomes a huge refuse dump for humankind. The film offers a number of solutions and carries a message of hope. We can’t get rid of plastic entirely - it’s too useful, but we can drastically reduce our consumption of single use items. My local shops offer paper bags for produce, which I always take. But we could do more. In New Zealand my daughter gave me some supermarket fruit and veggie bags as a present. They’re made from mesh fabric with a drawstring at the top and are washable. They’re completely transparent and replace the plastic bags that supermarkets encourage you to use to put your fruit and veg in and which invariably get thrown away as soon as you get home. If everyone used these it would cut out an enormous amount of plastic waste.

These new thoughts are affecting my reading habits too. E-readers are made from precious metals, plastics and other finite materials and the manufacturing process is not eco-friendly (or human friendly either as they’re often made in the ‘3rd’ world by poorly paid workers). A paper book is made from trees, which means that trees have to be planted and grown in large numbers. As trees help to take carbon out of the atmosphere, maybe that’s a good thing?

The dilemmas are everywhere. How does one lead an ethical life in the 21st century without retiring off-grid to live in a log cabin in the woods?

The state of the planet is the one concerning me most at the moment. Last week I went to a showing of the film A Plastic Ocean, made by a very distinguished team who worked on David Attenborough’s Blue Planet series, and it's narrated by journalist Craig Leeson who started out looking for the rare and elusive Blue Whale in order to film a documentary. What happened next was horrific. The diving team surfaced under a curtain of plastic pollution, much of which was going into the whales’ stomachs. As their search for the whale went on, they found more and more plastic accumulating in even the remotest parts of the ocean.

The plastic pollution of the ocean has intensified over the last decade to numbers that make your hair stand on end. Millions of tons of plastic waste go into the ocean every WEEK. And most of it comes from us and our addiction to single-use plastic. Supermarket carrier bags, drinking straws, fast-food trays, freezer bags, take-away cutlery, bottles of water . . . on and on and on. Some single-use plastic has an active life of only 10 minutes. The film showed the consequences for wild life and I have to say that it was upsetting. Endangered species are dying of starvation because they have stomachs full of plastic. Albatrosses are feeding plastic to their chicks, turtles are mistaking plastic bags for jellyfish, whales are sieving it out of the water instead of krill.

I have been trying not to buy plastic carrier bags from supermarkets - but I’m not perfect and there is always the time I forget to bring any with me. I try to recycle, but it’s not easy around here because the council don’t collect and it all has to be driven to the dump. I carry my own water bottle, but sometimes on a train I end up buying water in a bottle because there’s no way to get a clean refill.

It’s clear that we have to do something before the ocean becomes a huge refuse dump for humankind. The film offers a number of solutions and carries a message of hope. We can’t get rid of plastic entirely - it’s too useful, but we can drastically reduce our consumption of single use items. My local shops offer paper bags for produce, which I always take. But we could do more. In New Zealand my daughter gave me some supermarket fruit and veggie bags as a present. They’re made from mesh fabric with a drawstring at the top and are washable. They’re completely transparent and replace the plastic bags that supermarkets encourage you to use to put your fruit and veg in and which invariably get thrown away as soon as you get home. If everyone used these it would cut out an enormous amount of plastic waste.

These new thoughts are affecting my reading habits too. E-readers are made from precious metals, plastics and other finite materials and the manufacturing process is not eco-friendly (or human friendly either as they’re often made in the ‘3rd’ world by poorly paid workers). A paper book is made from trees, which means that trees have to be planted and grown in large numbers. As trees help to take carbon out of the atmosphere, maybe that’s a good thing?

The dilemmas are everywhere. How does one lead an ethical life in the 21st century without retiring off-grid to live in a log cabin in the woods?

Published on July 17, 2017 14:40

July 11, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Monsoon Poem by Tishani Doshi

Because this is a monsoon poem

expect to find the words jasmine,

palmyra, Kuruntokai, red; mangoes

in reference to trees or breasts; paddy

fields, peacocks, Kurinji flowers,

flutes; lotus buds guarding love’s

furtive routes. Expect to hear a lot

about erotic consummation inferred

by laburnum gyrations and bamboo

syncopations. Listen to the racket

of wide-mouthed frogs and bent-

legged prawns going about their

business of mating while rain falls

and falls on tiled roofs and verandas,

courtyards, pagodas. Because such

a big part of you seeks to understand

this kind of rain — so unlike your cold

rain, austere rain, get-me-the-hell-

out-of-here rain. Rain that can’t fathom

how to liberate camphor from the vaults

of the earth. Let me tell you how little

is written of mud, how it sneaks up

like a sleek-gilled vandal to catch hold

of your ankles. Or about the restorative

properties of mosquito blood, dappled

and fried against the wires of a bug-zapping

paddle. So much of monsoon is to do

with being overcome — not from longing

as you might think, but from the sky’s

steady bludgeoning, until every leaf

on every unremembered tree gleams

in the abyss of postcoital bliss.

Come. Now sip on your masala tea,

put your lips to the sweet, spicy skin

of it. There’s more to see — notice

the dogs who’ve been fucking on the beach,

locked in embrace like an elongated Anubis,

the crabs scavenging the flesh of a dopey-

eyed ponyfish, the entire delirious coast

with its philtra of beach and saturnine

clouds arched backwards in disbelief.

And the mayflies who swarm in November

with all their ephemeral grandeur to die

in millions at the behest of light, the geckos

stationed on living room walls, cramming

fistfuls of wings in their maws. Notice

how hardly anyone mentions the word

death, even though the fridge leaks

and the sheets have been damp for weeks.

And in this helter-skelter multitude

of gray-greenness, notice how even the rain

begins to feel fatigued. The roads and sewers

have nowhere to go, and like old-fashioned pursuers

they wander and spill their babbling hearts

to electrical poles and creatures with ears.

And what happens later, you might ask,

after we’ve moved to a place of shelter,

when the cracks in the earth have reappeared?

We dream of wet, of course, of being submerged

in millet stalks, of webbed toes and stalled

clocks and eels in the mouth of a heron.

We forget how unforgivably those old poems

led us to believe that men were mountains,

that the beautiful could never remain

heartbroken, that when the rains arrive

we should be delighted to be taken

in drowning, in devotion.

© Tishani Doshi

Source: Poetry (July/August 2017)

If you’d like to read the latest issue of Poetry online, which also includes Ocean Vuong, this is the link.

Tishani Doshi comes from southern India. She was born in the city of Chennai, formerly known as Madras, in 1975, to a Welsh mother and Gujurati father. She has published six books of poetry and fiction. Her essays, poems and short stories have been widely anthologized.

In 2012 she represented India at a historic gathering of world poets for Poetry Parnassus at the Southbank Centre, London. She is also the recipient of an Eric Gregory Award for Poetry, winner of the All-India Poetry Competition, and her first Book, Countries of the Body, won the prestigious Forward Prize for Best First Collection in 2006. It was launched at the Hay-on-Wye literary festival, on a platform that included Seamus Heaney and Margaret Atwood.

Tishani's debut novel, The Pleasure Seekers, published by Bloomsbury, was long-listed for the Orange Prize and the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award.

She currently lives on a beach between two fishing villages in Tamil Nadu with her husband and three dogs. Tishani Doshi is also a gifted dancer.

Her latest book is The Adulterous Citizen – poems stories essays (2015)

If you’d like to know more about Tishani Doshi, this is the link to her website: -

http://www.tishanidoshi.com/

Published on July 11, 2017 09:20

July 6, 2017

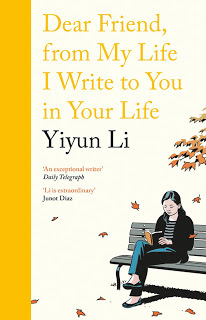

Dear Friend, from my life I write to you . . . Katherine Mansfield and Yiyun Li

The writer Katherine Mansfield is one of those extraordinary authors famous as much for her personal journals as for her fiction. Her notebooks contain some her best writing, partly because when she wrote in them she wasn't bound by the constraints of narrative or publication as they were perceived at the time. She was experimenting (not always successfully), exploring her motivations and the very darkest aspects of her own psyche. Hampered by illness, often on her own, her journal became her closest companion and recipient of her most intimate thoughts.

Yiyun Li

Yiyun Li

The Chinese author, Yiyun Li, admits being influenced by Katherine Mansfield to a considerable degree. Her latest memoir takes its title from a line in KM's journal, 'Dear Friend, from my life I write to you in your life'. Like Mansfield Yiyun Li has a problem with identity. She is Chinese, American, a writer, a scientist, a daughter, a sister, a mother, a wife, a friend, an exile, a depressive, a survivor, charting a passage through her life dragging them all in her wake. Katherine Mansfield, living in exile from her homeland, also felt a fragmentation of her personality. 'True to oneself!' she asks her journal. 'Which self? Which of my many - well, really, that's what it looks like coming to - hundreds of selves.'

Yiyun Li, brought up and educated in China, has difficulty with the 'I' word. She admits that she hates it. 'The moment that I enters my narrative my confidence crumbles'. In the Chinese language, the 'I' word is not often used and under the old regime such individualism was not encouraged. It was usual to use the impersonal pronoun, or to use 'we'. In China, Yiyun Li observes, 'Living is not an original business'. There is also considerable exposure in writing about oneself. 'To write one has to give up protection fundamentally.'

She feels that she no longer belongs anywhere and quotes another favourite author, the Irish John McGahern, with envy: 'The people and the language and landscape where I had grown up were like my breathing'. She longs to feel that, but, 'The paths I walked by myself in Beijing are gone. Even if the city had remained unchanged, I have turned away from the people and the language and the landscape'.

But Yiyun Li is 'haunted', a word which she explains is derived from the Middle English hauten (to reside, to inhabit), also from Old French hanter (to inhabit, frequent) and Old Norse heimta (to bring home, to fetch). 'When we feel haunted,' she writes, 'it is the pull of our old home we're experiencing.'

The author adopts a fragmented, journal style at the beginning of the book, morphing into longer narrative passages. The book was written after a period of suicidal despair and hospitalization - a period of self-interrogation that led to the memoir. Yiyun Li was a rebel in an institutionalized China, also in conflict with her 'wrathful and possessive' mother. She explores her relationships with her homeland, her family, with literature and the process of integration into American society. '. . . cruelty and kindness are not old stories,' she observes, 'and never will be.'

Finding Katherine Mansfield's journals was a life-changing moment for her. 'I devoured her words like thirst-quenching poison.' She read the notebooks 'to distract myself' and cried over them. 'What a long way it is from one life to another,' she observes, 'yet why write if not for that distance'?

Katherine Mansfield, with advanced Tuberculosis, at her desk.Yiyun Li destroyed most of her own journals and letters before she left China. Others she put in sealed boxes and has never opened them. 'One crosses the border', she says, 'to become a new person.' That person speaks a new language that takes on new meanings. One English saying struck her very hard - 'To kill time'. She interpreted it differently: 'no one thinks of suicide as a courageous endeavor to kill time'. This original take on her adopted language gives her writing a very particular flavour. 'Language is capable of sinking a mind', she asserts. In renouncing the mother-tongue, a great deal gets erased from memory. This loss, she admits 'is my sorrow and my selfishness'.

Katherine Mansfield, with advanced Tuberculosis, at her desk.Yiyun Li destroyed most of her own journals and letters before she left China. Others she put in sealed boxes and has never opened them. 'One crosses the border', she says, 'to become a new person.' That person speaks a new language that takes on new meanings. One English saying struck her very hard - 'To kill time'. She interpreted it differently: 'no one thinks of suicide as a courageous endeavor to kill time'. This original take on her adopted language gives her writing a very particular flavour. 'Language is capable of sinking a mind', she asserts. In renouncing the mother-tongue, a great deal gets erased from memory. This loss, she admits 'is my sorrow and my selfishness'.

As the title implies, this is a self-conscious narrative - not just 'an argument with myself' but a dialogue with an unknown, unseen reader. It is extraordinarily direct. But she states firmly that, 'A writer and a reader should never be allowed to meet. They live in different time frames. When a book takes on a life for a reader it is already dead for the writer.' From my own point of view, I'm not sure that this is true. My books are never dead to me - instead they develop rather frightening lives of their own and threaten to gallop off and become feral. And I love meeting readers to continue the dialogue that begins on the page. But I am not Yiyun Li.

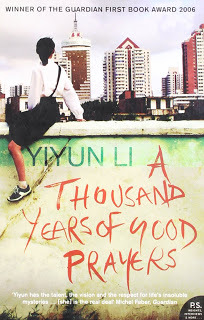

This is a wonderful book and the author's self-examination is threaded through with Katherine Mansfield's equally ruthless self-analysis. It made me think critically about the art of memoir and journal-writing, as well as concepts of identity and belonging. I've also ordered Yiyun Li's volume of short stories, A Thousand Years of Good Prayers and I'm looking forward to reading it. And many thanks to my friend Mel U, who has a wonderful book blog - The Reading Life - who emailed me to tell me about this book!

Yiyun Li

Yiyun LiThe Chinese author, Yiyun Li, admits being influenced by Katherine Mansfield to a considerable degree. Her latest memoir takes its title from a line in KM's journal, 'Dear Friend, from my life I write to you in your life'. Like Mansfield Yiyun Li has a problem with identity. She is Chinese, American, a writer, a scientist, a daughter, a sister, a mother, a wife, a friend, an exile, a depressive, a survivor, charting a passage through her life dragging them all in her wake. Katherine Mansfield, living in exile from her homeland, also felt a fragmentation of her personality. 'True to oneself!' she asks her journal. 'Which self? Which of my many - well, really, that's what it looks like coming to - hundreds of selves.'

Yiyun Li, brought up and educated in China, has difficulty with the 'I' word. She admits that she hates it. 'The moment that I enters my narrative my confidence crumbles'. In the Chinese language, the 'I' word is not often used and under the old regime such individualism was not encouraged. It was usual to use the impersonal pronoun, or to use 'we'. In China, Yiyun Li observes, 'Living is not an original business'. There is also considerable exposure in writing about oneself. 'To write one has to give up protection fundamentally.'

She feels that she no longer belongs anywhere and quotes another favourite author, the Irish John McGahern, with envy: 'The people and the language and landscape where I had grown up were like my breathing'. She longs to feel that, but, 'The paths I walked by myself in Beijing are gone. Even if the city had remained unchanged, I have turned away from the people and the language and the landscape'.

But Yiyun Li is 'haunted', a word which she explains is derived from the Middle English hauten (to reside, to inhabit), also from Old French hanter (to inhabit, frequent) and Old Norse heimta (to bring home, to fetch). 'When we feel haunted,' she writes, 'it is the pull of our old home we're experiencing.'

The author adopts a fragmented, journal style at the beginning of the book, morphing into longer narrative passages. The book was written after a period of suicidal despair and hospitalization - a period of self-interrogation that led to the memoir. Yiyun Li was a rebel in an institutionalized China, also in conflict with her 'wrathful and possessive' mother. She explores her relationships with her homeland, her family, with literature and the process of integration into American society. '. . . cruelty and kindness are not old stories,' she observes, 'and never will be.'

Finding Katherine Mansfield's journals was a life-changing moment for her. 'I devoured her words like thirst-quenching poison.' She read the notebooks 'to distract myself' and cried over them. 'What a long way it is from one life to another,' she observes, 'yet why write if not for that distance'?

Katherine Mansfield, with advanced Tuberculosis, at her desk.Yiyun Li destroyed most of her own journals and letters before she left China. Others she put in sealed boxes and has never opened them. 'One crosses the border', she says, 'to become a new person.' That person speaks a new language that takes on new meanings. One English saying struck her very hard - 'To kill time'. She interpreted it differently: 'no one thinks of suicide as a courageous endeavor to kill time'. This original take on her adopted language gives her writing a very particular flavour. 'Language is capable of sinking a mind', she asserts. In renouncing the mother-tongue, a great deal gets erased from memory. This loss, she admits 'is my sorrow and my selfishness'.

Katherine Mansfield, with advanced Tuberculosis, at her desk.Yiyun Li destroyed most of her own journals and letters before she left China. Others she put in sealed boxes and has never opened them. 'One crosses the border', she says, 'to become a new person.' That person speaks a new language that takes on new meanings. One English saying struck her very hard - 'To kill time'. She interpreted it differently: 'no one thinks of suicide as a courageous endeavor to kill time'. This original take on her adopted language gives her writing a very particular flavour. 'Language is capable of sinking a mind', she asserts. In renouncing the mother-tongue, a great deal gets erased from memory. This loss, she admits 'is my sorrow and my selfishness'. As the title implies, this is a self-conscious narrative - not just 'an argument with myself' but a dialogue with an unknown, unseen reader. It is extraordinarily direct. But she states firmly that, 'A writer and a reader should never be allowed to meet. They live in different time frames. When a book takes on a life for a reader it is already dead for the writer.' From my own point of view, I'm not sure that this is true. My books are never dead to me - instead they develop rather frightening lives of their own and threaten to gallop off and become feral. And I love meeting readers to continue the dialogue that begins on the page. But I am not Yiyun Li.

This is a wonderful book and the author's self-examination is threaded through with Katherine Mansfield's equally ruthless self-analysis. It made me think critically about the art of memoir and journal-writing, as well as concepts of identity and belonging. I've also ordered Yiyun Li's volume of short stories, A Thousand Years of Good Prayers and I'm looking forward to reading it. And many thanks to my friend Mel U, who has a wonderful book blog - The Reading Life - who emailed me to tell me about this book!

Published on July 06, 2017 06:32

July 3, 2017

Tuesday Poem: baby grand by Allie Spensley - Foyle Young Poet of the Year 2015

my father showed me how a piano could cleave a room

like a fault line, how a dance could keep you deathless:

the eighty-eight teeth in a piano's mouth chewing up

strips of sheet music like so many pieces of bubblegum.

my father had pounded his fingers into skeleton keys

and molded their locks out of smooth ebony and ivory.

he wore ragtime like a coat and sipped jazz like hot

tea with lemon and spice, danced his way across the

underground platform because there was a sort of music

written on his bones, notes wrapped like handcuffs

around his wrists, rhythms coursing through his

syncopated veins, his piano was his cross and he bore it

through windy city december, from hubbard street

down to west belmont, his face reflecting neon light,

his body buzzing with the notes of the trumpets

like a hot vibrato on his skin, my father's only altar

was a midnight jazz joint; music was his finest language

so I couldn't blame him if he cursed arpeggios all up

and down our kitchen walls, couldn't blame him

if his magic fingers twisted in my mother's hair to

make music that was sour as a dying trombone,

couldn't blame his "please, i'm trying to practice,

just leave me alone, my music, i'm sorry, my music."

© Allie Spensley 2015

Reproduced with permission.

The Young Poet's Award, for poets between the ages of 11 and 17, was founded by the Poetry Society in 1998 and funded by the Foyle Foundation in 2001. Entries are usually in excess of 12,000 poems from all over the world. The judges have to sift out 15 young poets for their prize-winning list. Not an enviable task, but it often throws up some remarkable results.

Ever wondered what happened to all those emerging poets? Allie Spensley was one of the Foyle Young Poets of the Year in 2015. Her poem ‘baby grand’ was the one that stood out for me in the Poetry Society anthology of winning poets, so I thought I’d find out what she was doing now and tracked her down on Facebook.

Allie is from Avon Lake, Ohio, a small town on the shores of Lake Eerie, and she’s now a sophomore at Princeton University, New Jersey. She's been a prize-winner in other poetry competitions too, including Writing for Peace. Her work has been published in The Guardian, and BOXCAR Poetry Review, among others. It's a brilliant start for someone so young.

According to her online profile, she’s been writing for as long as she can remember, but only started seriously reading and writing contemporary short fiction/poetry a few years ago. Allie is passionate about education, particularly in areas with low literacy rates or where girls are prevented from attending school.

In this poem, I love the lack of capitals and the way the lines run on. I like the use of images and metaphors and the way the poem leans into darkness towards the end. There's an undertow of menace.

I think we might be going to see a lot more poetry from Allie Spensley in future - I certainly hope so!

PS congratulations to the Young Poets of 2016, Malika Booker and W.N. Herbert picked out 15 entries from more than 76 countries. It's a very diverse selection. You can see them here.

like a fault line, how a dance could keep you deathless:

the eighty-eight teeth in a piano's mouth chewing up

strips of sheet music like so many pieces of bubblegum.

my father had pounded his fingers into skeleton keys

and molded their locks out of smooth ebony and ivory.

he wore ragtime like a coat and sipped jazz like hot

tea with lemon and spice, danced his way across the

underground platform because there was a sort of music

written on his bones, notes wrapped like handcuffs

around his wrists, rhythms coursing through his

syncopated veins, his piano was his cross and he bore it

through windy city december, from hubbard street

down to west belmont, his face reflecting neon light,

his body buzzing with the notes of the trumpets

like a hot vibrato on his skin, my father's only altar

was a midnight jazz joint; music was his finest language

so I couldn't blame him if he cursed arpeggios all up

and down our kitchen walls, couldn't blame him

if his magic fingers twisted in my mother's hair to

make music that was sour as a dying trombone,

couldn't blame his "please, i'm trying to practice,

just leave me alone, my music, i'm sorry, my music."

© Allie Spensley 2015

Reproduced with permission.

The Young Poet's Award, for poets between the ages of 11 and 17, was founded by the Poetry Society in 1998 and funded by the Foyle Foundation in 2001. Entries are usually in excess of 12,000 poems from all over the world. The judges have to sift out 15 young poets for their prize-winning list. Not an enviable task, but it often throws up some remarkable results.

Ever wondered what happened to all those emerging poets? Allie Spensley was one of the Foyle Young Poets of the Year in 2015. Her poem ‘baby grand’ was the one that stood out for me in the Poetry Society anthology of winning poets, so I thought I’d find out what she was doing now and tracked her down on Facebook.

Allie is from Avon Lake, Ohio, a small town on the shores of Lake Eerie, and she’s now a sophomore at Princeton University, New Jersey. She's been a prize-winner in other poetry competitions too, including Writing for Peace. Her work has been published in The Guardian, and BOXCAR Poetry Review, among others. It's a brilliant start for someone so young.

According to her online profile, she’s been writing for as long as she can remember, but only started seriously reading and writing contemporary short fiction/poetry a few years ago. Allie is passionate about education, particularly in areas with low literacy rates or where girls are prevented from attending school.

In this poem, I love the lack of capitals and the way the lines run on. I like the use of images and metaphors and the way the poem leans into darkness towards the end. There's an undertow of menace.

I think we might be going to see a lot more poetry from Allie Spensley in future - I certainly hope so!

PS congratulations to the Young Poets of 2016, Malika Booker and W.N. Herbert picked out 15 entries from more than 76 countries. It's a very diverse selection. You can see them here.

Published on July 03, 2017 16:30

June 30, 2017

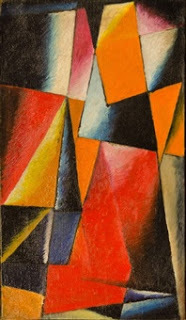

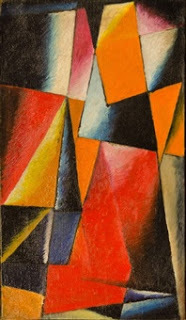

The Unfinished Life of Lyubov Popova

When I visited the Revolution exhibition of Russian art at the Royal Academy, one of the artists that interested me most was a woman called Lyubov Popova. Her paintings were striking and very beautiful. But there were only a few and even fewer details of her life. I wondered why. What had happened to Popova?

Lyubov Popova photograhed by Alexander RodchenkoOn the internet I uncovered the story of her life. She was born into a wealthy and highly educated family in 1889. Her father was a textile merchant and patron of the arts. Her mother also came from an artistic family. Popova's precocious talent was encouraged from the beginning. Initially she was taught at home, then at the Gymnasium in Moscow before entering the private studios of some of the best artists in Russia, studying Cubism and Futurism, developing her own blend which she called Architectonics.

Lyubov Popova photograhed by Alexander RodchenkoOn the internet I uncovered the story of her life. She was born into a wealthy and highly educated family in 1889. Her father was a textile merchant and patron of the arts. Her mother also came from an artistic family. Popova's precocious talent was encouraged from the beginning. Initially she was taught at home, then at the Gymnasium in Moscow before entering the private studios of some of the best artists in Russia, studying Cubism and Futurism, developing her own blend which she called Architectonics.

Lyubov Popova - ArchitectonicPopova travelled widely in Russia looking at the tradition of Icon painting. She was also interested in European Renaissance art - particularly Giotto - and in 1913 she went to Paris to study there, following this with a tour of France and Italy, returning after the outbreak of war in 1914. She studied with Cubists Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger. Her privileged background made all of this possible.

Lyubov Popova - ArchitectonicPopova travelled widely in Russia looking at the tradition of Icon painting. She was also interested in European Renaissance art - particularly Giotto - and in 1913 she went to Paris to study there, following this with a tour of France and Italy, returning after the outbreak of war in 1914. She studied with Cubists Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger. Her privileged background made all of this possible.

Lyubov Popova - Female Study

Lyubov Popova - Female Study

Initially the war and the increasing instability in Russia had little effect on Popova. She became interested in Constructivism and worked for a while in the same studio as Vladimir Tatlin. Then she was admitted to the studio of Kazimir Malevich who was an enormous influence on her.

The lives of every artist in Russia changed with the revolution in 1918. After this, the approval of the State was necessary for your work. Many were unable to work under its restraints and left. Popova remained. In 1918 she married the art historian Boris Eding, with whom she had a son. The following year, with Russia in chaos, Eding died of typhoid fever. Popova was ill, but recovered.

Popova continued to paint, but began, like many other artists, to use her talents to design everyday objects. She was particularly interested in fabric and fashion . Her paintings reflect this fascination with patterns. Popova, alongside another female artist, Stepanova, laid down strict conditions for working as artists in commercial conditions, trying to achieve a measure of artistic freedom.

In 1924, Popova's young son contracted Scarlet Fever and died. Two days later Popova also died - the life and career of a brilliant artist cut short. She was only 34. Her younger brother, Pavel, became the guardian of her estate and reputation. As with the author Katherine Mansfield, who died at the same age and almost in the same year, it would be very tempting to go into the 'might-have-beens', but instead it is better to look at what had already been achieved. Lyubov Popova left a huge body of work, some of it utterly stunning.

The Life and work of Lyubov Popova

Lyubov Popova - Encyclopaedia Britannica

Exhibition history - MOMA

Lyubov Popova photograhed by Alexander RodchenkoOn the internet I uncovered the story of her life. She was born into a wealthy and highly educated family in 1889. Her father was a textile merchant and patron of the arts. Her mother also came from an artistic family. Popova's precocious talent was encouraged from the beginning. Initially she was taught at home, then at the Gymnasium in Moscow before entering the private studios of some of the best artists in Russia, studying Cubism and Futurism, developing her own blend which she called Architectonics.

Lyubov Popova photograhed by Alexander RodchenkoOn the internet I uncovered the story of her life. She was born into a wealthy and highly educated family in 1889. Her father was a textile merchant and patron of the arts. Her mother also came from an artistic family. Popova's precocious talent was encouraged from the beginning. Initially she was taught at home, then at the Gymnasium in Moscow before entering the private studios of some of the best artists in Russia, studying Cubism and Futurism, developing her own blend which she called Architectonics. Lyubov Popova - ArchitectonicPopova travelled widely in Russia looking at the tradition of Icon painting. She was also interested in European Renaissance art - particularly Giotto - and in 1913 she went to Paris to study there, following this with a tour of France and Italy, returning after the outbreak of war in 1914. She studied with Cubists Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger. Her privileged background made all of this possible.

Lyubov Popova - ArchitectonicPopova travelled widely in Russia looking at the tradition of Icon painting. She was also interested in European Renaissance art - particularly Giotto - and in 1913 she went to Paris to study there, following this with a tour of France and Italy, returning after the outbreak of war in 1914. She studied with Cubists Henri Le Fauconnier and Jean Metzinger. Her privileged background made all of this possible. Lyubov Popova - Female Study

Lyubov Popova - Female StudyInitially the war and the increasing instability in Russia had little effect on Popova. She became interested in Constructivism and worked for a while in the same studio as Vladimir Tatlin. Then she was admitted to the studio of Kazimir Malevich who was an enormous influence on her.

The lives of every artist in Russia changed with the revolution in 1918. After this, the approval of the State was necessary for your work. Many were unable to work under its restraints and left. Popova remained. In 1918 she married the art historian Boris Eding, with whom she had a son. The following year, with Russia in chaos, Eding died of typhoid fever. Popova was ill, but recovered.

Popova continued to paint, but began, like many other artists, to use her talents to design everyday objects. She was particularly interested in fabric and fashion . Her paintings reflect this fascination with patterns. Popova, alongside another female artist, Stepanova, laid down strict conditions for working as artists in commercial conditions, trying to achieve a measure of artistic freedom.

In 1924, Popova's young son contracted Scarlet Fever and died. Two days later Popova also died - the life and career of a brilliant artist cut short. She was only 34. Her younger brother, Pavel, became the guardian of her estate and reputation. As with the author Katherine Mansfield, who died at the same age and almost in the same year, it would be very tempting to go into the 'might-have-beens', but instead it is better to look at what had already been achieved. Lyubov Popova left a huge body of work, some of it utterly stunning.

The Life and work of Lyubov Popova

Lyubov Popova - Encyclopaedia Britannica

Exhibition history - MOMA

Published on June 30, 2017 04:37

June 27, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Cloud Chamber by Janet Sutherland

in a new light the river

water weightier

than oil or slub

viscous slip

beer-bottle brown

you notice don't you

language clarifies

or chant these slim diminutives:

rivulet rill run burn beck

runnel freshet torrent force jet

and riveret (now rare or obsolete)

none of them hold

such corrugations welded from below

such heavy fish

etched as with acid from cast steel

these gate-keeper

herons iron posts

charting a route

you might well walk beside

bright air above

cloud trails scraps gnats slant swifts in flight

© Janet Sutherland

Watermarks Anthology, The Frogmore Press, 2017

I thought about this poem the other evening when, after a very long, hot drive from the southern end of England, we finally arrived back at the Mill on the banks of the river Eden. We had a 'carrier bag' picnic with salads and wine bought at a service station on the motorway and then, looking at the weir - calm and cool reflecting the evening sky - we stripped off and threw ourselves into the beer-bottle brown water and let the river wash the journey away. I lay in the river (which smells unromantically of ducks) and watched the clouds drifting across as the swifts wheeled and screamed overhead searching for low-flying insects.

We live in the country of burns and becks and are familiar with torrents when the river is in flood and its weight pushes everything in front of it. The 'gate-keeper/herons' stand guard on the weir every morning in the ever-changing light.

I'm a great fan of Janet Sutherland's poetry, which doesn't always follow the route you expect it to. I particularly liked her collection Bone Monkey, from Shearsman. Bone Monkey is a shamanistic creature from mythology, who keeps popping up in different disguises. Sometimes he's 'a grinning ape', or 'a bone-thin workman with a sly look', or 'a hangman in a tattered vest'. He's a trickster - out of time, elemental. The poetry is similarly slippery - always shearing off in unexpected directions and difficult to pin down for analysis. I like to be surprised; I like to be taken out of my comfort zone. I want my hair to stand on end when I read!

One of my favourite poems from the collection is a beautifully crafted, more conventional poem called 'My Red Morocco Jack Boots'. Bone Monkey is currently an English Gentleman abroad in Illyria in 1846 and definitely up to no good when he spies a vulnerable Serbian woman.

There are seven stations between Belgrade and Alexnitza

where changing horses takes an hour. At Pashapolanca

we had bread and slivovitz then lay on hard board

and slept very soundly. In white caps and German blouses,

Turkish trousers, with twelve yards of stuff, and jack boots

(mine were red morocco) our cavalcade moved off.

At night the path was very striking, summer lightning

pierced the dense foliage. I am not a Romantic . . .

If you would like to read the whole of the poem, this is the link -

You can buy

Bone Monkey from Amazon.co.uk

You can buy

Bone Monkey from Amazon.co.uk

Janet's poem 'Cloud Chamber' is featured in the Watermarks Anthology of Wild Swimming published by Frogmore Press.

You can buy it here.

Janet's poem 'Cloud Chamber' is featured in the Watermarks Anthology of Wild Swimming published by Frogmore Press.

You can buy it here.

water weightier

than oil or slub

viscous slip

beer-bottle brown

you notice don't you

language clarifies

or chant these slim diminutives:

rivulet rill run burn beck

runnel freshet torrent force jet

and riveret (now rare or obsolete)

none of them hold

such corrugations welded from below

such heavy fish

etched as with acid from cast steel

these gate-keeper

herons iron posts

charting a route

you might well walk beside

bright air above

cloud trails scraps gnats slant swifts in flight

© Janet Sutherland

Watermarks Anthology, The Frogmore Press, 2017

I thought about this poem the other evening when, after a very long, hot drive from the southern end of England, we finally arrived back at the Mill on the banks of the river Eden. We had a 'carrier bag' picnic with salads and wine bought at a service station on the motorway and then, looking at the weir - calm and cool reflecting the evening sky - we stripped off and threw ourselves into the beer-bottle brown water and let the river wash the journey away. I lay in the river (which smells unromantically of ducks) and watched the clouds drifting across as the swifts wheeled and screamed overhead searching for low-flying insects.

We live in the country of burns and becks and are familiar with torrents when the river is in flood and its weight pushes everything in front of it. The 'gate-keeper/herons' stand guard on the weir every morning in the ever-changing light.

I'm a great fan of Janet Sutherland's poetry, which doesn't always follow the route you expect it to. I particularly liked her collection Bone Monkey, from Shearsman. Bone Monkey is a shamanistic creature from mythology, who keeps popping up in different disguises. Sometimes he's 'a grinning ape', or 'a bone-thin workman with a sly look', or 'a hangman in a tattered vest'. He's a trickster - out of time, elemental. The poetry is similarly slippery - always shearing off in unexpected directions and difficult to pin down for analysis. I like to be surprised; I like to be taken out of my comfort zone. I want my hair to stand on end when I read!

One of my favourite poems from the collection is a beautifully crafted, more conventional poem called 'My Red Morocco Jack Boots'. Bone Monkey is currently an English Gentleman abroad in Illyria in 1846 and definitely up to no good when he spies a vulnerable Serbian woman.

There are seven stations between Belgrade and Alexnitza

where changing horses takes an hour. At Pashapolanca

we had bread and slivovitz then lay on hard board

and slept very soundly. In white caps and German blouses,

Turkish trousers, with twelve yards of stuff, and jack boots

(mine were red morocco) our cavalcade moved off.

At night the path was very striking, summer lightning

pierced the dense foliage. I am not a Romantic . . .

If you would like to read the whole of the poem, this is the link -

You can buy

Bone Monkey from Amazon.co.uk

You can buy

Bone Monkey from Amazon.co.uk

Janet's poem 'Cloud Chamber' is featured in the Watermarks Anthology of Wild Swimming published by Frogmore Press.

You can buy it here.

Janet's poem 'Cloud Chamber' is featured in the Watermarks Anthology of Wild Swimming published by Frogmore Press.

You can buy it here.

Published on June 27, 2017 06:22

June 24, 2017

A crazier, sadder week you could hardly describe

I think the stars must be in an alien alignment - or I would if I was medieval, or of a superstitious nature. At a personal level it's been chaotic. I have been up and down to Kent trucking sculpture, I've been to/through London twice, given a talk to the James Street Literary Salon, done my last Reading Round in Cumbria and a poetry reading in Yorkshire. All against a background of terrorist attacks, the horrendous fire at Grenfell Tower, the Brexit shambles, Trump idiocy, massacres in Syria and Iraq (mysteriously ignored by mainstream media obsessed by Theresa May's facial expressions and the Queen's hat), a cholera epidemic in Yemen (ditto) and the ominous rumblings of a middle eastern showdown between Qatar (where I used to live) and its opponents. Now it's Saturday and I'm trying to remember where I left what remains of my mind.

Shoreham sculpture trail was one of the high points. Some wonderful sculptures (some of them Neil's) in a water meadow belonging to one of the houses, with spectacular roses scrambling through trees. There was a river, a pond and a boat house. When you have a lot of money, you can afford tranquility. With Grenfell Tower on the news as an ever present monument to inequality, it was impossible to ignore the wealth and privilege we were surrounded by.

One of the best things was being able to see my grandchildren.

This was not a dinner gong but a magical crescent moon sculpture, by Marigold Hodginson, which can be rocked to and fro.

The down side was having to spend a sweltering day at 33 degrees, driving a white van from Kent to the Lake District via a jam-packed M25!

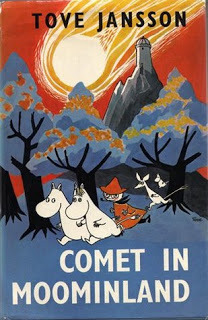

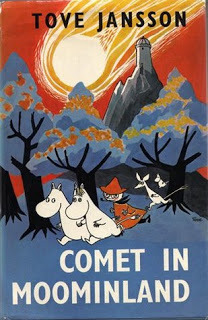

I took a train down to London again the following day and it was even hotter. Although officially only 34.5 C max, the sun beating off the pavements and buildings created a sauna - one street thermometer I saw read 40 degrees. London felt as though it was simmering. The air crackled. There were armed police everywhere. I'm very glad I don't live in the capital. Sadly, the Moomin experience I had tickets to visit was cancelled because of the heat. I've loved Tove Janssen's books since I was a child. They are very philosophical - layers of meaning that children don't necessarily pick up. But adults do. The cancellation made me very sad. If this is climate change - it can only get hotter and more difficult. In Comet in Moominland, the comet scorches the earth as it flies past and all the animals have to take cover underground. That's exactly how London felt.

At the James St. Salon we all sweated unapologetically. I was giving a talk on switching from conventional to Indie publishing and there were a lot of interested authors - all well-published but now struggling with their current publishers and dissatisfied with the system. There is very little transparency in main-stream publishing; you get paid once very 6 months, no-one tells you how many books have been printed/are out on review/in bookshops and publisher's accounts sheets need an accountant to decipher them. As an Indie author you get paid every month and you have a dashboard that shows exactly where every book has gone. I recommended the Alliance of Independent Authors' website for help and advice.

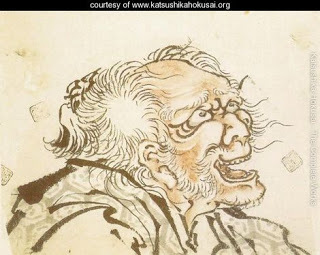

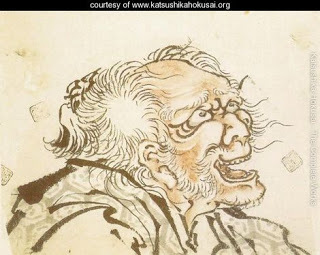

The Hokusai exhibition at the British Museum was an absolute delight and well worth queuing through the new security system to get into. They've erected a tent in the courtyard and you have to queue behind crash barriers to be screened. The exhibition itself was very unexpected. As well as the beautiful indigo paintings of the Great Wave and the views of Mount Fuji there are notebooks, personal material, and a lot of other paintings and prints that show just how versatile he was and also what a fantastic sense of humour he must have had. This is his painting of a summer thunderstorm, complete with bare bottoms as robes are blown aloft by the wind.

And this is himself as an old man. He admitted that he had large ears. Hokusai believed that as an artist and master craftsman he got better with every decade that he aged. 'I did nothing worth looking at until I was 70,' he insisted. Some comfort there then!

After hot, crowded, jittery London, the Settle Sessions couldn't have been more of a contrast. Settle is a beautiful old town in the Yorkshire dales, next to Giggleswick, home to Alan Bennett. The Folly, where the poetry readings are held, is a Grade 1 listed building gradually being restored. Alan Bennett has been involved in the fund raising. It was a fabulous venue and very enjoyable poetry from my 'partner in rhyme' Ron Scowcroft, published by Wayleaves Press.

Now looking forward to a cooler, quieter week at home. Please. Oh, and could we have some more cheerful news just for a change?

Shoreham sculpture trail was one of the high points. Some wonderful sculptures (some of them Neil's) in a water meadow belonging to one of the houses, with spectacular roses scrambling through trees. There was a river, a pond and a boat house. When you have a lot of money, you can afford tranquility. With Grenfell Tower on the news as an ever present monument to inequality, it was impossible to ignore the wealth and privilege we were surrounded by.

One of the best things was being able to see my grandchildren.

This was not a dinner gong but a magical crescent moon sculpture, by Marigold Hodginson, which can be rocked to and fro.

The down side was having to spend a sweltering day at 33 degrees, driving a white van from Kent to the Lake District via a jam-packed M25!

I took a train down to London again the following day and it was even hotter. Although officially only 34.5 C max, the sun beating off the pavements and buildings created a sauna - one street thermometer I saw read 40 degrees. London felt as though it was simmering. The air crackled. There were armed police everywhere. I'm very glad I don't live in the capital. Sadly, the Moomin experience I had tickets to visit was cancelled because of the heat. I've loved Tove Janssen's books since I was a child. They are very philosophical - layers of meaning that children don't necessarily pick up. But adults do. The cancellation made me very sad. If this is climate change - it can only get hotter and more difficult. In Comet in Moominland, the comet scorches the earth as it flies past and all the animals have to take cover underground. That's exactly how London felt.

At the James St. Salon we all sweated unapologetically. I was giving a talk on switching from conventional to Indie publishing and there were a lot of interested authors - all well-published but now struggling with their current publishers and dissatisfied with the system. There is very little transparency in main-stream publishing; you get paid once very 6 months, no-one tells you how many books have been printed/are out on review/in bookshops and publisher's accounts sheets need an accountant to decipher them. As an Indie author you get paid every month and you have a dashboard that shows exactly where every book has gone. I recommended the Alliance of Independent Authors' website for help and advice.

The Hokusai exhibition at the British Museum was an absolute delight and well worth queuing through the new security system to get into. They've erected a tent in the courtyard and you have to queue behind crash barriers to be screened. The exhibition itself was very unexpected. As well as the beautiful indigo paintings of the Great Wave and the views of Mount Fuji there are notebooks, personal material, and a lot of other paintings and prints that show just how versatile he was and also what a fantastic sense of humour he must have had. This is his painting of a summer thunderstorm, complete with bare bottoms as robes are blown aloft by the wind.

And this is himself as an old man. He admitted that he had large ears. Hokusai believed that as an artist and master craftsman he got better with every decade that he aged. 'I did nothing worth looking at until I was 70,' he insisted. Some comfort there then!

After hot, crowded, jittery London, the Settle Sessions couldn't have been more of a contrast. Settle is a beautiful old town in the Yorkshire dales, next to Giggleswick, home to Alan Bennett. The Folly, where the poetry readings are held, is a Grade 1 listed building gradually being restored. Alan Bennett has been involved in the fund raising. It was a fabulous venue and very enjoyable poetry from my 'partner in rhyme' Ron Scowcroft, published by Wayleaves Press.

Now looking forward to a cooler, quieter week at home. Please. Oh, and could we have some more cheerful news just for a change?

Published on June 24, 2017 15:04