Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 2

March 12, 2021

Racism, Misogyny, and a Cobra in the Bath

After we left the Middle East, scouting round for something else to do, my husband met a man who owned a small civil engineering consultancy in West Africa, nominally fronted by a Ghanaian with political connections. Chris was offered a job in charge of their office in Accra, with oversight of contracts in Nigeria as well. If he was successful, he would be offered a partnership. He relished the opportunity to work for himself and Africa sounded very attractive. But the position was conditional on his wife’s social suitability, as the job would entail a lot of entertaining. I had to be vetted.

I left the children with a baby-sitter and went to London for this ordeal by misogyny. We were taken out to a high-end restaurant for a meal. I wore a yellow silk shift dress I’d made myself – very simple but displaying an intricate gold collar necklace that had come from the jewellery suekh in Dubai, courtesy of one of the Sheikhs. My apparent metamorphosis from gawky girl to young executive wife was almost complete, at least on the outside. When I left home at sixteen I had never eaten in a restaurant, but now, thanks to all those Embassy dinners in the Middle East, I knew the intricacies of cutlery and crystal and the basic etiquette of a formal social occasion. I spoke only when spoken to, watched my vowels, and only picked up a fork once my host’s wife had done so. I feigned an interest in the different models of Rolls Royce being discussed and made polite noises at the high Tory views expressed by Mr B-H, my husband’s future employer. If everyone worked hard enough, apparently, no one need be poor. It was all about ‘graft’. Chris told them I was a farmer’s daughter from the Lake District; I was suitably vague about my background. At the end of the evening I felt like a complete fraud.

I must have passed the test because Chris was offered the job the following day and we celebrated. I would have gone almost anywhere to have a permanent home again. ‘I do hope you’re going to be safe,’ my mother said over the phone. ‘Don’t be silly,’ I told her, ‘You’re such a worrier!’ It was all going to be fine. Ghana was a stable country, which had until recently been ruled, after independence from Britain, by Kwame Nkrumah. Everything I read led me to believe that it was civilised. There was a photograph of a colonial style villa with a mango tree in the garden. It would be another adventure. For my mother it was another bitter separation, but she never questioned it because she believed that it was a woman’s duty to go with her husband. Before I left, she gave me her war-time engagement ring, which she could no longer wear on her arthritic fingers. I didn’t see her again for nearly three years.

We flew to Accra on a Ghana Airways flight that was different to any other I’d been on. The plane was battered and shabby, the organisation of the boarding procedure chaotic. Passengers were fighting over seat allocations and luggage space. One of them had a parrot in a cage. The plane took off from Heathrow five hours late and it was pitch dark when we landed. From the window of the plane I could see the lights on the apron – each beam a whirling column of insects. When the cabin doors were opened the humidity and the smell poured in. It was primitive, raw and so thick I could taste the stench of rotting vegetation, refuse, sewage and hot, wet earth.

On the evening of our first day, we were taken to the British Club and formally enrolled. There was a swimming pool, tennis and squash courts and a small theatre. Broad verandas were laid out with steamer chairs and bamboo tables in the shade of mature palm trees. Black waiters in white uniforms walked around with cocktails on trays. It was like a movie set. The faces of the guests were, without exception, white. ‘Are there any Ghanaian members?’ I asked. ‘Oh goodness, no!’ was the answer. ‘This isn’t their sort of thing at all. It’s not that we exclude them, of course, they just don’t want to join.’ It was a conversation that revealed a racism so deeply entrenched in the system it could easily be ignored.

I quickly fell out of love with Africa. It had great beauty, but also a frenetic, almost obscene fertility. The floors of the house had to be mopped with paraffin every week to prevent termites from eating the wood. The legs of the bed sat in little jars of paraffin to prevent the ants from devouring us. A preying mantis, a foot long, sat behind the toilet door ambushing mosquitoes. The rows of beans I planted in the garden were eaten by pests before they had a chance to grow. One morning there was a baby cobra curled up in the bath, having crawled up the drain. After the first coup there was chaos and violence everywhere I looked. It was not unusual to drive into town and pass a dead body lying by the side of the road, sometimes for days. One of our neighbours was stabbed to death when they disturbed thieves in the house during the night.

Six months into our contract, I was arrested by a policeman at gunpoint as I drove the children to school one morning. He held up his hand and stepped out into the road at a traffic crossing in the centre of town. When I stopped, he climbed into the front seat of the car and ordered me to drive to the police station. I had been observed driving dangerously, he said. But half a mile up the road he began to tell me that he was only a poor man and I was a rich European woman and he didn’t really want to arrest me at all. If I was generous to him, he would let me go. I had the children’s school fees in my bag. With shaking hands I took the roll of money out and gave it to him. He got out of the car, put his gun in its holster, and walked away. I was never sure that he was a real policeman; there were a number of cases of fake policemen committing crimes.

In colonial society racism and misogyny go together. I experienced both from the clients Chris was expected to entertain. We took one of them, an Africaan engineer from South Africa, out to a nightclub called La Rene, where he leered at the hostesses, called them ‘Mammies’ and the waiters ‘Kaffir’. He had a hard, young face with little mean eyes. He claimed, within earshot of the staff, that black people were animals – even the dogs could smell them in the bush. I had to swallow my outrage and smile politely, for the sake of Chris’s business, when I really wanted to kick his teeth in.

Another man, head of a big corporation, who had been in Africa for more than thirty years, invited us to dinner in his palatial colonial-era residence. We drove up a long, curving driveway between immaculate lawns, with fragrant hedges of Oleander and Hibiscus. The mansion was old style, a heritage building of polished floors, carved screens and antique furniture. The dinner was formal. Every chair had a servant behind it in a white suit and turban, with a tea cloth over their arms, standing to attention like a military platoon. I was struggling with mosquitoes on a particularly sticky night. My host noticed and signalled to the man behind my chair. ‘Boy! Fetch the Off’. The man returned with a canister of insecticide on a silver drinks’ tray. As I reached up for it, my host commanded, ‘Boy! Spray madam’s legs.’ I felt utterly humiliated by the sight of this elderly, dignified man, kneeling on the floor to spray me with mosquito repellant. ‘You have to treat them with authority,’ my host announced to the dinner table, presumably for my benefit. ‘I treat mine like children. I take care of them, but every now and then they must be chastised.’ His idea of punishment was to slap their outstretched hands. It was an extension of the colonial model. Ghana, like many other former colonies, was regarded as a ‘young’ country, not grown-up enough to be able to look after its own affairs without the oversight of its colonial betters. Political and economic chaos was regarded as a kind of juvenile delinquency.

Colonel Acheampong announcing his takeover on the radio

After the second attempted coup, as the country tumbled into bankruptcy, the English owner of the company came out on a visit to assess the situation. Chris told me that I had to be on my best behaviour to impress. He was still on probation, hoping to become a full partner. I was expected to entertain Mr B-H at our house, alongside a few other selected guests. Finding ingredients suitable for a dinner party was a challenge without foreign currency. After a visit to the market I planned to have baked fish with creamed yam, a kind of dumpling called fufu with spicy palm oil stew, plantain crisps, a salad of tomatoes and onions, and coconut pudding.

That morning, my Head Boy scalded his arm in the kitchen and was taken to hospital. Desperate for help with a menu that was beyond my skill level, a friend leant me her cook and her ‘small boy’ as a waiter. As this was a dinner jacket affair I got out the big silver platters and asked the cook to make sure they were clean before using them for food. Then I went to get dressed. It was a hot night and I chose to wear a dress with a long skirt, split to thigh level, very flattering and cool. Everything appeared to go quite well. I hadn’t been able to find any wine, so I had made a rum and fruit punch – the only way to make the local spirit drinkable. The guests were quite merry. The cook and the small boy managed the silver service really well, balancing the salvers on their palms high above their shoulders and using two spoons to scoop the food onto the plate. I noticed, as they served the creamed yam that each scoop was green underneath and realised, with a sinking heart, that the cooks had cleaned the silver with polish and neglected to wash the dishes before putting the food on them. What was I supposed to do? It was the main part of the meal and had taken all day to prepare. I decided that I simply wasn’t going to notice and if any of the guests did, they could simply leave the food on the side of the plate. Drowned in the bright crimson palm oil sauce it was possible to miss it. But worse was to come.

Halfway through the main course I felt a hand on my left knee. As I was sitting at right angles to Mr B-H, who was at the head of the table, it could only be him. I froze. The hand began to work its way up my bare thigh, to the edge of my pants. I looked indignantly at my husband’s boss but he wasn’t looking at me. He was talking to the man on the opposite side of the table while he tried to wriggle his fingers underneath the elastic. He had a satisfied smile on his face as he talked, and I knew that he was enjoying my discomfiture, knowing that I would never dare to make a fuss in front of clients; knowing that I would never jeopardise my husband’s job. Feeling sick, I excused myself, got up and went to the bathroom.

I felt angry for days afterwards and could hardly bring myself to be polite for the remaining time of his stay. On his final night he told Chris he would like to go to the nightclub ‘for a little fun’ and I claimed a headache and let them go alone. Being sexually assaulted by the boss seemed to be just one of the things an executive wife was expected to handle as part of the job description.

March 8, 2021

The 'Trailing' Wife: International Women's Day

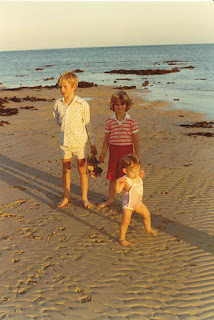

By the time my third child was born at the age of 28, I'd moved 29 times, visited 18 countries and lived in 4 of them. The logistics of packing and moving, and establishing a functional family life wherever we were, was always left to me. It was what women did. During ten years of marriage I'd lived in hotels, B&Bs, with relatives, in rat-infested flats, cockroach-ridden Arabian villas, African bungalows, and an assortment of rented, furnished accommodation. I was what was known as a 'trailing' wife. I followed my husband wherever he went, dragging the children with me. They lived it too and there were some very happy times.

A beach in the United Arab Emirates

But there were other times too. By the time the older children were 10 they had been to 7 different schools. We lived out of suitcases and steamer trunks. we coped with military coups, power cuts in 48 degrees of heat, economic collapse, and accident and illness in third world countries without proper medical facilities. It left its mark on all of us, physically and mentally. But it made us resilient. When I was growing up on a remote hill farm in the Lake District, I never saw myself bribing my way onto an aeroplane during a coup in an African state dissolving into chaos. This is an extract from a memoir:

Mrs Boshung's Nursery School, Ghana before the coup

The peaceful situation after the first military coup didn’t last. Within months there was a counter-coup, a rebellion by rival military officers, and this time not so benign. My husband, Chris, was in Nigeria, negotiating another contract and unable to return when the country’s borders were abruptly closed. I realised something had happened when my steward, Richard, didn’t come to work, so I turned on the radio to hear the familiar martial music. The telephone network was down, so I walked down to a neighbour’s house to be told that soldiers were looting the town and I should go home and lock myself in. At lunchtime Paul, the garden boy, arrived and hammered on the sliding door. I let him in. He looked pale and was carrying two machetes. He gave one to me. ‘The soldiers are coming,’ he said, ‘you must make everything safe.’ We made sure every window was closed, the curtains drawn, every door locked and furniture moved against them. Paul sat inside the kitchen door, machete in hand, and I got the children into their bedroom, barricaded the door and crouched on the floor, with the other machete, knowing that I might have to use it. Then the soldiers came, running round the house, banging on the walls, running their rifle butts over the bars, firing the guns into the air, shouting ‘Yi! Yi! Yi!’. I pushed the children under the bed and shielded them with my body. And then the soldiers were gone, but we could hear the gunfire out in the cantonments. Some of the empty houses were ransacked.

The coup failed, but it was two days before Chris could get back from Lagos. The schools and shops were closed for a week. Even though things began to go back to normal our lives changed very quickly. There were military roadblocks on every road, the banks didn’t always have money when you went in to withdraw cash. The airports were crowded with foreign nationals returning home. It was announced that, because of the corruption of the previous government, the country was bankrupt. The cedi ceased to be traded on the international money exchanges. The IMF proposed stringent terms for a loan, which the military council refused. Imported goods no longer arrived. Medicines, including anti-malarial drugs, were unobtainable and, overnight, essential food vanished from the supermarket shelves. Local fruit and vegetables were still on sale in the market, though prices doubled, but all the imported meat, cheese and other staple foods, cereal, dairy products, sugar, flour, rice, coffee and tea, as well as washing and hygiene products became a memory.

Riots in Ghana

Hotels and restaurants closed. Only the restaurant belonging to the Minister of the Interior, who had a Swiss wife, remained open for anyone who could afford the prices. My diary records being taken out to dinner by a client and stealing the sugar lumps out of the bowl on the table. On April 4th the car broke down, and a month later I wrote, ‘Still no car for lack of spare parts. . . we are without indefinitely’. But the flame trees were vibrant with red plumes and the orchid tree was a mass of creamy bloom. Long-tailed Whyddah birds performed cheerful acrobatics on the telephone wires every morning. The government brought in rationing for essentials and a flourishing black market sprang up for goods smuggled in from neighbouring Togo and Sierre Leone.

Anyone paid in hard currency could drive over the border, fill up their car boot at Carrrefour and drive back, bribing the border guards with cigarettes and whisky. Because we were paid in local currency we didn’t have that option, and inflation meant that Chris’s salary halved in value overnight. He employed a boy at the office whose job it was to scour the town for food. The Foreign Office advised all those who could to leave. Chris still had six months to run on his contract, which we were expected to fulfill, before the firm would pay for a flight back to the UK. I could have left with the children, but there was no home to go to and no money to pay for us to live anywhere but Ghana. I realised that I was totally dependent on my husband.

Travelling children: a railway station somewhere in China

Pets were being abandoned by fleeing Europeans. I went with a friend to rescue two cats from a neighbour’s house, and we acquired a guard dog from another. He was a strange mixture of bush dog and long-haired English Sheepdog. The children loved him but, we discovered too late, that he’d been trained to be very aggressive with people whose skin was not white. As we had many Ghanaian friends, this was embarrassing. It was also difficult for the staff. I had to lock Watson on the veranda before my steward, Richard, would clean the house. But there was no doubt that I felt safer. No policeman was going to hi-jack my car with Watson on the back seat; and any thief was going to think twice about breaking into the house with him there. At the British club, the pool began to turn an unhealthy shade of green as chlorine supplies failed to arrive. The steamer chairs were empty and, when you ordered a drink at the bar, you first had to ask what they had behind the counter. Very few Europeans were left. We huddled together like survivors of a shipwreck.

The Centre of Accra

The next attempted coup happened a few months later as the military officers argued amongst themselves. One of the Colonels wanted to set up an interim civilian administration pending democratic elections. By coincidence, Chris was again absent. An Italian friend, Piero, had planned a trip up-country to check on his timber suppliers and had offered to take Chris, and my son David, with him. They intended to go to the far north, on the border with Burkina Faso, where the land turned into savannah and there was a lot of wildlife, giraffes, elephants and leopards. This was a Boys’ Own adventure. Piero argued that his car wasn’t big enough to take me and two-year-old Peta as well. Chris thought she wasn’t old enough for such a rough expedition anyway.

Two days after they left I woke up and found that none of the staff had come to work. I gave Peta her breakfast, listening to the martial music on the radio, and recognised the familiar sound of gunfire in the distance. Surrounded now by empty houses, remembering the last time, I felt very afraid. I made up my mind to leave if I could. There had been roadblocks on the main roads since the previous coup, so driving out wasn’t an option, even if I’d had enough fuel and a reliable car. The telephone line was still connected, so I rang the airport and was told it was open for internal flights, though the borders had been closed. I grabbed a suitcase, threw some clothes into it, ransacked the house for whatever money I could find, let the dog out into the garden, put my daughter into the car and drove to the airport using only the back streets.

At the airport, the departure lounge was rammed with people. I asked the ticket clerk what planes were leaving and was told there was only one flight for Kumasi in the north, already boarding.

‘I would like a ticket please,’ I said.

‘But it is full madam,’ he replied.

I put some money on the desk. ‘I have to be on that flight,’ I said. ‘Please?’ Peta had begun to cry and I picked her up. I put some more money on the desk and then some more, feeling suddenly quite desperate. Eventually he took the cash and reluctantly issued me with a ticket.

The plane was a WWII Douglas DC 3. There were holes in the fuselage. The pilot, a veteran Australian with blood-shot eyes, was going through the cabin, redistributing the passengers to balance the weight. He kept counting and re-counting them. I kept very quiet, sitting on one of the crew seats at the back with Peta on my lap. He asked two African women for their tickets, which were in order, but didn’t check mine. Still puzzled, he closed the doors and soon we were taxiing out to the runway. I felt nauseous with relief. As we skimmed the rain forest, I could see the tops of the kapok trees through the floor, but we skidded safely down the runway in Kumasi.

I had no plan beyond getting out of Accra and knew no one in the north. After we landed, I shared a cigarette and a can of warm Fanta with the pilot on the grass beside the runway. He was curious to know what I was doing there and, when I told him the story, he suggested I go into town and enquire about the government guest house. I remembered that there was a branch of the firm’s bank, Standard and Chartered, in Kumasi, so I took a taxi there. The manager, a smiling man called Joe, came to the reception desk and said, ‘I’ve just seen your husband!’ Chris, David and Piero, were staying at the guest house on the edge of town.

We spent the night in the guest house, discussing what we were going to do. Peta and I could have stayed there for a few more days before returning to Accra, but the situation was so unstable, we couldn’t be sure that Kumasi wouldn’t be affected. I was also reluctant to go back on my own. In the end it was decided that I should go with them. After some juggling of luggage, fuel cans and an improvised roof rack, we all crammed into Piero’s old Peugeot and headed north for Bolgatanga and Burkina Faso.

February 2, 2021

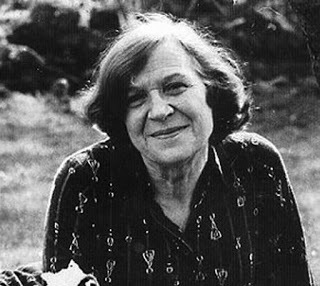

Jessie Kesson: The White Bird Passes

I was recently introduced to the work of Scottish author Jessie Kesson. She was a novelist, poet and playwright who did a lot of work for the BBC, but also a nature writer and friend of Nan Shepherd. Jessie was the illegitimate child of a woman who lived in the tenements of Glasgow and, through poverty, drifted into casual prostitution. Jessie was taken into care and brought up in orphanages while her mother died slowly and painfully of syphilis.

Although intellectually brilliant, the ‘training schools’ of Scotland only equipped girls for a life in service. Instead of going to university, as she wished, Jessie worked as a servant until she met her husband, an agricultural worker. For the first decade of her married life, Jessie was a ‘cottar wife’ – working on the farms alongside her husband, living in ‘tied’ houses, with no security and very little money.

Although intellectually brilliant, the ‘training schools’ of Scotland only equipped girls for a life in service. Instead of going to university, as she wished, Jessie worked as a servant until she met her husband, an agricultural worker. For the first decade of her married life, Jessie was a ‘cottar wife’ – working on the farms alongside her husband, living in ‘tied’ houses, with no security and very little money.

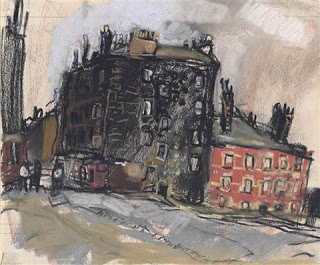

The Glasgow Tenements painted by Joan Eardley Jessie became a published writer, encouraged by Nan Shepherd, a stranger she met on a train. Critics talked about ‘Kesson’s consummate ability to catch the moment passing; that transitional, trembling point of awareness of life as painful yet delightful, dangerous yet desired . . . As always in Kesson, there is that sense of a pool of light beyond which the darkness lowers’. (Books in Scotland) Her account of life in the tenements reminds me very much of the paintings of Joan Eardley.

The Glasgow Tenements painted by Joan Eardley Jessie became a published writer, encouraged by Nan Shepherd, a stranger she met on a train. Critics talked about ‘Kesson’s consummate ability to catch the moment passing; that transitional, trembling point of awareness of life as painful yet delightful, dangerous yet desired . . . As always in Kesson, there is that sense of a pool of light beyond which the darkness lowers’. (Books in Scotland) Her account of life in the tenements reminds me very much of the paintings of Joan Eardley.

Jessie was a protégé of Carmen Callil, published by Virago. But it was as a broadcaster that she was best known. I’ve just discovered her novel, The White Bird Passes, a fictional account of growing up in the tenements and being taken into care. It’s a novel written by a poet and playwright. The descriptions of place are stunning, the characters leap off the page and the dialogue is so brilliant you can close your eyes and hear them talking to you. No wonder that it was turned into a film.

Jessie was a protégé of Carmen Callil, published by Virago. But it was as a broadcaster that she was best known. I’ve just discovered her novel, The White Bird Passes, a fictional account of growing up in the tenements and being taken into care. It’s a novel written by a poet and playwright. The descriptions of place are stunning, the characters leap off the page and the dialogue is so brilliant you can close your eyes and hear them talking to you. No wonder that it was turned into a film.The White Bird Passes - Film

Towards the end of the book, the young girl, told that she must leave the shelter of the orphanage, stands on the edge of the wild land, listening to the wind. She’s full of passion and wild emotions she doesn’t know how to handle.

‘. . . the aloneness of the night was beyond the bearing of the land itself. It caught you, the land did, if you walked it at night. Held you hostage. Clamped and small within its own immensity, and cast all the burden ot its own aloneness upon you. The wind had begun to threaten the air. Passionately she had longed for the wind to come. To blow herself and the landscape sky high into movement and coherence again. Almost she had been aware of the wind’s near fierceness. Ready to plunge the furious hillside burns down into Cladda river. To hurl the straws over all the dykes. To toss the chaff into the eyes of protesting people, bending before it, flapping in their clothes like scarecrows. To sting the trees in Carron wood into hissing rebellion.’

How sad that such a fantastic novel has almost vanished from view. I’m grateful that it has been re-issued, and I’ve now found others, which are on my TBR list.

December 24, 2020

The Meeting place of Four Kings in 926

A few hundred yards away is what is locally known as Arthur’s Round Table, which is also circular, with a raised central stage, like an ampitheatre.

A few hundred yards away is what is locally known as Arthur’s Round Table, which is also circular, with a raised central stage, like an ampitheatre.

A third henge was destroyed a hundred years ago by road building. Mayburgh is gigantic – surrounded by a circular boundary of stones, four metres high, now covered over with grass and oak trees.

Mayburgh is where, in 926, King Athelstan (grandson of King Alfred of the burnt cakes) met with King Owain of Strathclyde and Cumbria, Constantine, King of the Scots, King Hywel Dda of Wales and Earl Ealdred of Northumberland. Each of the kings would have had a considerable retinue, but Mayburgh is big enough to accommodate over a thousand people. Here the Kings agreed the Treaty of Eamont Bridge, which effectively made Athelstan King of all England. The kings then rode to Dacre, where there was a monastery, established in 713 (later demolished by the Vikings). There’s a moated Norman castle now at Dacre, and a church where the monastery was. But in the ancient, overgrown churchyard four strange, carved figures, pre-Saxon, believed to be pagan.

Mayburgh is where, in 926, King Athelstan (grandson of King Alfred of the burnt cakes) met with King Owain of Strathclyde and Cumbria, Constantine, King of the Scots, King Hywel Dda of Wales and Earl Ealdred of Northumberland. Each of the kings would have had a considerable retinue, but Mayburgh is big enough to accommodate over a thousand people. Here the Kings agreed the Treaty of Eamont Bridge, which effectively made Athelstan King of all England. The kings then rode to Dacre, where there was a monastery, established in 713 (later demolished by the Vikings). There’s a moated Norman castle now at Dacre, and a church where the monastery was. But in the ancient, overgrown churchyard four strange, carved figures, pre-Saxon, believed to be pagan.

It’s a fascinating place, thick with yew trees, and one of the old graves, twined with ivy, and with its own sundial, looks like Aslan’s Table or something else out of mythology. Made me realise that in 5000 years time none of this Boris/Trump/Covid stuff will really matter.

November 25, 2020

Sojourner Truth: One of our forgotten 'Mothers'.

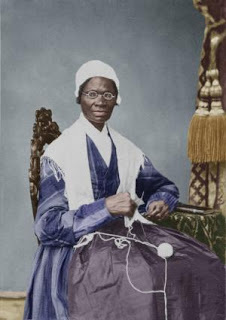

Today is the anniversary of the death of the woman we know as Sojourner Truth. She was born as Isabelle ‘Belle’ Baumfree in New York State. Her parents were slaves and her first language was Dutch. She was sold at the age of nine with a flock of sheep to another owner who ill-treated her. She was sold again, at least twice, finally to an owner who raped her, as was common practice at the time. As a result she gave birth to two children – a boy who died in childhood and a girl called Diana. The man she loved, also a slave, was savagely beaten by his owner when they were discovered together and he died shortly afterwards. Marriage to another slave produced three children, before ‘Belle’ ‘walked away’ in her words, with her youngest child, and was taken in by an abolitionist family in New York, the Van Wagenens, who kept her until the Emancipation Act became law and she could be officially freed.

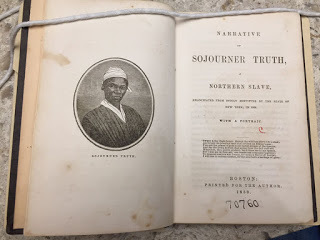

Meanwhile her previous owner had sold her son Peter at the age of five to a family in Alabama. Belle sued to get him back, in 1828, with the help of her protectors, and was the first woman of colour to win a case against a white man. Peter had been badly abused by his owners. In 1842 he sailed in a whaler from Nantucket. Belle received two letters from him, but when the ship returned to port, Peter had disappeared. The loss of her second son affected her deeply. Belle had become an evangelical Christian while living with the Van Wagenens and in 1843 became a Methodist, claiming that God had instructed her to go out into the countryside to preach the truth and campaign against slavery. She changed her name to Sojourner Truth. At almost six feet tall, she was an imposing figure with an air of calm and strength that impressed everyone she met. Her preaching and singing attracted large crowds wherever she went. In 1850 she dictated a memoir to friends, and it was published as The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: a Northern Slave.

In 1851 she attended the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention, giving the speech we now know as ‘Ain’t I a Woman?’ In it she argued passionately for rights for all women regardless of colour. Unable to read or write, Truth spoke extempore, and various versions of her speech were published afterwards, some of them in a southern dialect quite alien to Truth, who was a New Yorker and spoke English with a Dutch accent. Slavery was often seen as a southern issue. She was also credited with thirteen children in some versions, rather than the five she herself claimed. But, whatever the details, the content of the speech electrified all who heard it and was an inspiration for second wave feminists and anti-apartheid activists in the 20th century.

“That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages, and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain't I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?”

If you’d like to know more about her original speech click here: https://www.thesojournertruthproject.com/

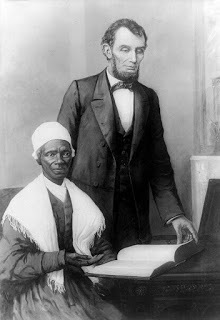

Her activism brought her into contact with Harriet Beecher Stowe and Abraham Lincoln. She is reported to have ridden the streetcars in Washington to protest at their segregation, making a precedent for 20th century Rosa Parks. Truth lived in Battle Creek, Michigan with her daughter Elizabeth until her death in 1883, campaigning for social justice until the end. Her funeral attracted almost a thousand mourners. She was the first black woman to have her bust placed in the US Capitol building, Washington, in 2009. Another statue appears in Central Park NY.

If you would like to know more, there’s a very comprehensive account of her life and achievements on Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sojourner_Truth

November 6, 2020

Photoshopping the Dead

Since I began writing a memoir about my mother, I’ve spent a lot of time going through old family photographs and letters. Some of the material I’ve found is unfamiliar. Over the years, since I left home, albums and letters have come down to my mother from grandparents and other relatives. Among these I came across the strange photograph of a girl who I presumed was one of my great aunts. My grandmother was originally one of five daughters, but three of her sisters died of tuberculosis between the ages of twelve and twenty.

They were a working-class family, living in a two-up-two-down terraced house in Denton Holme, Carlisle, in the shadow of Dixon’s Mill, where their father worked as a pattern maker. I knew very little about the girls who died – my Carlisle grandmother didn’t talk much about intimate things. One of them, my father understood, had lived to become a welder during WW1 and I found a photograph of her dressed for war work in a kind of mob cap and all in one ‘boiler’ suit. Another, with pretty curly hair, appears in a group photo with her two surviving sisters, aged about sixteen. This is Aunt Etty in her boiler suit.

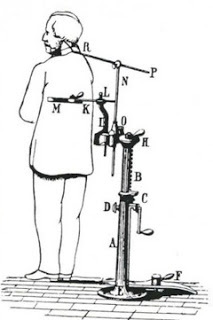

The photograph that caught my attention was of a schoolgirl, about eleven or twelve, standing in an awkward pose, leaning against a plant stand draped with trailing greenery. Something about the way she was standing wasn’t quite right – the way the dress hung on her, one arm stiffly by her side with the hand at a strange angle. It was only then that I realised what I was looking at.

The Victorians were very keen on post-mortem photography. It seems ghoulish to us now, but many lower-middle or working-class families couldn’t afford to have photographs taken. So, when a beloved member of the family died suddenly, a photograph would be taken as a memento mori. The first one I ever saw, was in the Katherine Mansfield archives in New Zealand. Katherine’s baby sister, Gwen, died of cholera at a few months old and there’s a poignant photograph of their grandmother sitting in the nursery in front of the doll’s house, holding the dead baby who is immaculately laid out in what looks like a christening dress.

Then I went to a reading by a poet called Jennifer Copley, who had written a series of poems using these post mortem images as a starting point. I was surprised (though I shouldn’t have been) to find that there was a huge archive on the web for this genre. Jennifer explained the process in detail, and it was one of the most interesting poetry readings I’ve ever been to, and also one of the saddest.

The Victorians had lots of clever technology to enable them to take life-like photographs – not just of the loved one lying sleeping, like Katherine Mansfield’s baby sister, but of them standing up in a natural pose as if they were still living. Iron braces were used to support the body, before it was dressed and arranged, often using pieces of furniture as props to enhance the effect. After the photograph was taken, the face would be expertly touched up and the eyes painted to give the impression of life.

It may seem strange to us now, but earlier generations were less squeamish about death than we are. And we still take photographs of stillborn babies in their mother’s arms to give comfort to bereaved families.

You never know what is in your family album until you look. I just wish there was someone still alive to tell me the stories behind the faces.

October 19, 2020

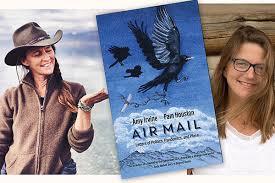

Airmail: Writing Letters in a Time of Pandemic

It was while I was still in a state of admiration and envy at the re-election of Jacinda Ardern as New Zealand’s amazing premier, that I opened my current bedtime book and read ‘We are coming, I am sure of it, to either the end of the letting men be in charge of the world period of history, or the end of the human race’.

This observation is in a letter written by an author I love – Pam Houston to her friend, American author Amy Irvine. The two women live in Colorado, one each side of the mountain range. This is red MAGA country, ‘where mud and mountains and bringing home meat for the freezer’ is paramount, but both women are Democrats. They have chosen to set up home in the wilderness and try to live as eco-friendly an existence as they can. Until the arrival of the Covid Pandemic, their challenges had been mostly how to keep their horses, sheep and cattle from being eaten by bears or incinerated in wild fires. Both are outspoken feminists with histories of abuse and complicated relationships. Anyone who has read Pam Houston’s wonderful short stories, Cowboys are my Weakness, will understand what I mean.

They were already struggling under the man they describe as the ‘Monster in Chief’, when Covid arrived. Living in a Republican heartland has not been easy and has suddenly become more difficult:

‘agreeing to disagree isn’t going to cut it anymore as I watch this administration attack and destroy every single thing that brings me joy: air and water, trees and animals, every slice of wildness we have left, but also the arts, education, diversity itself.’

After the arrival of the virus confined them to their individual territories (Amy has a vulnerable daughter) someone suggested that they write letters to each other, recording their lives in lockdown. Both women were struggling to write in isolation. ‘I tried most of the afternoon to work on an essay and got mostly nowhere, but in correspondence the words come more easily.’ What has emerged is a sad, beautiful, funny, revelatory record of what it’s like to live in Trump’s America, in the age of Covid – ‘How we were, together apart’.

Pam Houston and her partner on her Colorado ranch

Pam Houston and her partner on her Colorado ranchPam reflects that she would rather die being hugged by a Black Bear than a MAGA hatted Republican without a mask. The future is uncertain. The Pandemic is a hiatus, an ‘in between’, a pause, a place ‘between the world as it was and the world as whatever it will be after’. To Amy the pandemic feels inevitable ‘the natural expression of greed and corruption gone completely unrestrained.’ She also sees both the response to Covid and the climate catastrophe as an extension of toxic masculinity.

‘It’s never been so clear to me, this umbilicus between misogyny and the devastation of the natural world. . . As a woman who likes men a great deal . . . it’s hard to admit that such hatred exists’.

The book asks the question ‘what sort of stories do we tell now’? It challenges what it calls ‘the whitewashing [rightly named] of history’, that is buried so deep within the language we use to tell those stories it could render us dumb trying to eradicate it. Pam asserts her faith in ‘the concrete nouns of the world’, and believes that ‘we can build the world we want to live in, and we must, because time is short and inaction is death. Fighting for the Earth and each other will be the only way to feel how alive we still are.’ It’s an interesting choice of verb. In the state of Colorado gun checks have gone from averaging fifty in the system at any one time, to thirteen thousand.

This is an amazing book that kept me involved and also had me pencilling notes and underlining sentences on almost every page. The fact that I've scribbled all over it is a sign that this is a must-read!

Torrey House Press, October 2020

September 21, 2020

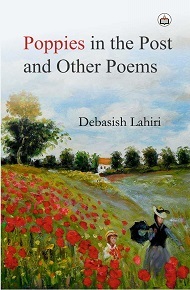

Tuesday Poem: Debasish Lahiri, An Unsent Letter, (for Paul Celan)

The introduction to Debasish Lahiri’s collection has been written by Mansfield scholar, editor and TLS critic Gerri Kimber, who describes it as ‘a confident, animated collection of poems . . . deeply rooted in Western classical mythology, whilst at the same time reflecting his Indian roots’.

This is a very unusual combination, but if we are surprised by it, then that reflects attitudes we need to examine. As Debasish says, in his interview below: “In a world that is seemingly cosmopolitan writers should have the freedom to write about any subject or idea under the sun and not be limited by the colour of their skin or the stamp on their passport. A writer from India need not only write about things Indian.” Instead of advancing towards multi-culturalism we seem to be stepping backwards at the moment, reinforcing cultural and national boundaries.

Debasish speaks five languages and his poems have also been translated into French. The influence of France is very prominent in the collection, which contains poems dedicated to Paul Celan, and others inspired by Cezanne, Monet and Van Gogh. One of Gerri’s favourite poems is also one of mine. It’s called ‘Colours by Rain’ and describes a journey that Debasish made to Van Gogh country at Auver-sur-Oise.

On a morning, Like today, When the sky brooding on itself Had forgotten its own colours, Moved by a painter’s question, A man had found them: Colours, Huddled into a navel of quiet, All the colours that had escaped The sky’s palette.

I didn’t always find this poetry easy. I’m not a fan of capitalisation at the beginning of the line and the detailed references to classical mythology stretched my own understanding of the Greek myths to the limit and had me reaching for the Dictionary of Mythology. I sometimes found the mix of Indian and Western mythologies confusing. But there is some fine poetry, as in ‘a blind blacksmith/Forges stars on this page/That I cannot see.’ And ‘Look at what blood does to us./ In giving us life/ It kills us by saying/ That time is soon gone.’ In another poem, I’m taken straight to the Bazaars of Hyderabad and one of those spine-tingling moments I recognise from my own time in the east:

Suddenly a muezzin calls to prayer The very air of the place. A cannonade of startled pigeons Bursts through the thin indifference I had carried into the square.

Debasish lectures in English at Lalbaba College, affiliated to the University of Calcutta, and received the Naji Naaman merit literary prize in 2019. Poppies in the Post has also been reviewed in Academia magazine.

An Unsent Letter (For Paul Celan)To reply,VerbTo write,VerbActions that perform The true rites Of my passageThrough this Paris of secrets well-lostThe pain of disclosuresSurmounted by an idle rainLike a café offering its summer munificence.

Why should I write beautiful lines in this city?Will the chestnut bloom twice if I do?Autumn always calls onceAnd Provencal bees do not storm summerOn Rue de Luxembourg.This is another hum,And traffic loiters in awe of it.

Death-beetle summer,Summon your autumn Elysium.

To write,Verb,To scratch the itch of tears,Now dry,To remember,Verbs too.Shall I send poppies in the post?

(Paris, 2017)

I asked Debasish 10 questions about his work, which he was kind enough to answer.

1. Tell me a little about yourself - where were you born and brought up?

I was born and brought up in the suburbs of Kolkata, a city with a distinct colonial identity and a pronounced Anglophilia. From kindergarten onwards I was admitted to the Don Bosco school, an institution run by a Catholic order called Society of Saint Francis de Sales or the Salesians. Being there for twelve years has been a vital shaping influence in my life.

2. How did you start writing?

My first, albeit slightly confused, steps in writing were taken in school when I was in the seventh standard. Heavily influenced by the poets prescribed in the syllabus I got it into my head that all writing had to be chiselled out on paper in the shape of a structured poem. I started this somewhat bizarre experiment with my student essays much to the mystification and often ire of my teachers. I think it was bizarre for them, not for me, because I quite enjoyed it.

Any way, transgressions like this piled up and I was brought to, what seemed at the time to be a trial, before our rector Fr. Patrick Sheehy. Grades had been suffering and everyone was rather concerned. To my great surprise, and also relief, Fr. Sheehy did not chide me. The benign Irish rector who never raised his voice above a soft whisper was grandfatherly. He weaned me away from my experiments but only by offering me another avenue: to write as I pleased and to bring it to him for his scrutiny. Besides he opened the doors to his personal library every weekday for my use. That's where I discovered the poets.

3. What brought you to poetry?

It took me till my eleventh standard in school to realise that what I was writing was mostly poetry, mostly bad poetry. I say bad because that was a long apprenticeship in words, in structure, in the sound of, in the fall of the notes of poetry; an apprenticeship that was clumsy and imitative at the best of times. It was perhaps around that time that I also realised that mere structure on a page was not something that was tantamount to poetry: there was the voice and the content, the idea or an insight that was necessary for a scribble to become poetry. Frankly, most of what I was writing by the time I finished school and went to college was, looking back, in speech rhythm, a half-dramatic, half-confessional set of monologues. Poetry was for me a way of living and engaging with the society, with the world around me, without really doing so. I was, and still am, very much an introvert by nature.

4. How many languages do you speak?

I can speak in English, in Hindi and Urdu, and Bengali of course, it being my mother-tongue. My French is very halting, sadly.

5. How difficult is it to write in another language?

In fact, it was quite easy to write in English for me, almost inevitable. Let me explain. I have already said that Kolkata - Calcutta - as it was spelt earlier, had an ingrained Anglophone culture thanks to its establishment and provenance by British colonial fiat. In my own house English was a language I had heard spoken from my earliest childhood. My father was very comfortable in the language and I grew up happily bilingual. In school English was accentuated. So when it came to choosing a language in terms of writing, English was a natural choice. And never did I feel afterwards that I had abandoned Bengali in favour of English: there was no guilt.

6. Which authors do you like reading? Have you a favourite book?

Amongst the poets I like reading are Homer, Virgil, Cavalcanti, Shakespeare, Keats, T.S. Eliot, Philip Larkin, Keki Daruwalla and Arun Kolatkar. Among prose writers Daniel Defoe, Tobias Smollett, Laurence Sterne, Dickens, Maugham, Joyce, and Rushdie. My favourite books would be Sterne's Tristam Shandy, Shakespeare's Sonnets, Larkin's High Windows and Kolatkar's Jejuri.

7. Who are your biggest influences?

In life my biggest influences have been my parents, and next to them Fr. Sheehy, and my English teachers in school Mr. Diaz and Mr. Allaphad.

In my poetry Keats, Eliot and Larkin have been strongest as influences. Later the Russian poets, Akhmatova, Pasternak and Mandelstam along with Neruda have been shaping and inspiring presence. Further, I cannot but acknowledge the role played by Keki Daruwalla as a mentor and inspiration in my early years as a poet.

8. You draw from a number of mythologies; what fascinates you about our cultural contexts and the mythical landscapes we inhabit?

I have always held that mythologies are merely powerful imaginative projections of situations we encounter in daily life. I read mythology as archetypes of the everyday that we can invoke, access and enter into organically a myriad number of times without affecting its original freshness and appeal. That is why I use myths, western and oriental in my poetry, not as stilts, but as natural outcrops of language, situation and emotion. A rose that bloomed in an Athenian garden in the 5th century is the same rose that bloomed in the garden of a Mughal Emperor in the 16th century and is the same rose that blooms in my neighbour's garden nigh. It is the same rose, but it is also different. I use myth, like the rather bruised-by-overuse metaphor of the rose, that I have outlined.

The nature myths and the myths of resilient figures in western mythology attracts me particularly as I feel one aspect of the appreciation of beauty is the strength and patience to endure. The one prized moment of rapture in the presence of the beautiful is presaged by privation, suffering and long silence.

9. Is there anything else you want to say?

No tall claims, or oracular statements. Just this: In a world that is seemingly cosmopolitan writers should have the freedom to write about any subject or idea under the sun and not be limited by the colour of their skin or the stamp on their passport. A writer from India need not only write about things Indian. He/She could as well choose to write about Roman Britain, or Italy during the Great War or anything else for that matter as long as a sense of authenticity and regard for cultural specificity colours every act of imagination. - It is often the case that publishers also discriminate between writers of different countries writing in English. If I try a British publisher with a manuscript of poetry in English without an obvious British connection, I will be asked to try an Indian publisher. Whereas an Indian publisher can and often do tell me to find European avenues because my poetry is too western. My poems are strewn with references to both oriental and occidental mythologies and realities, where then do I pitch my poems? - Just the travails of writing in a world that swears by cosmopolitanism.

10. What are you working on at the moment?

Here's the catch. I've finished putting together a short collection of poems on the lives of common-folk in Roman Britain. A British Publisher will be bringing it out in 2021.

Additionally, I've just finished writing forty poems on Miniature Paintings from India, from the 11th to the 17th centuries which I hope will form a collection in the near future.

Thank you so much for asking me these questions and allowing me to open up on some aspects of my writing.

Poppies in the Post by Debasish Lahiri

Authors Press, Delhi, 2020

September 10, 2020

Reading My Mother: 50 elderly sheep and a lame horse

Eventually my parents begged and borrowed from every relative they could, took out an agricultural mortgage and bought a small, marginal, fell farm at the back of Skiddaw in the Uldale fells. It had been empty for almost ten years and could only be reached across a ford and almost a mile of rough track.

Rough Close as it is now

It’s impossible to over-estimate the importance of Rough Close in all our lives. It meant everything to us. For the first time we had somewhere to belong. This land was ours; we owned it. For my brother and I, it became a place of magical enchantment; for my mother it was the ‘dear perpetual place’ where she could make long-term plans; it was my father’s life-long dream – a farm of his own, with no one to tell him what to do. He was thirty-two, my mother four years older.

We arrived on a cloudy northern day in two cattle wagons that lumbered and lurched their way over the ford and up the rough track. Our possessions were in one, the animals in another. The front door was open and a fire had been lit in the grate of the black range. A woman in an overall was on her knees scrubbing the stone flags. She got to her feet shyly and introduced herself as Nellie, one of our new neighbours. A kettle was hanging from the hook over the fire and soon we all had mugs of hot tea. She had brought an apple cake to eat and as soon as we were finished she melted away before my mother had time to thank her properly. It was our first experience of the kindness of the northern fells. In a couple of hours the furniture was all in the right rooms, if not in the right places and the beds had been screwed together so that we could sleep in them as night fell.

Skiddaw (England's 3rd highest mountain) and Overwater, our nearest lake.

While my mother unpacked sheets and towels and wrestled pillows into their cases, my father was out in the barns and byres settling the small stock he had brought with him from Low Ling; Prince the horse, Jennifer and her flock of daughters and grand-daughters, two cows with their calves and Flo the collie. It was a small beginning. Dad intended to use the money they had saved to buy more sheep and cattle at auction in the weeks that followed.

One of the shires between the shafts

Dad took me to auction with him and I listened to the incomprehensible patter of the auctioneers, which he seemed to understand, above the noise of anxious cattle, sheep calling lost lambs and men shouting to be heard over the din. On that first day, Dad bought fifty ‘cast’ ewes. These were sheep that had had several lambs and were now past their best. They were usually sold for pet food, but Dad knew the farmer who had kept these particular ewes. He looked at their teeth and their feet and reckoned that they were likely to have another two or three lambs apiece and their offspring would give him the flock he needed at a fraction of the price. Even after he’d paid the obligatory ‘luck money’ to the vendor, he thought they were a bargain. Other farmers thought he was mad.

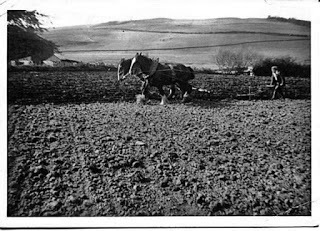

In the pens at the back of the mart were the horses. Although some milkmen, breweries and delivery firms still used horses, most businesses were modernising. Milk carts were going electric, the railways had converted to three-wheeled Scammell flatbeds. Petrol driven lorries were taking over everywhere. Farming had also mechanised during the war and tractors were now doing the hard work that horses had done before. My father had never learned to drive. He was happier with four legs than four wheels. Horses, he said, were kinder to the land than tractors, they were also environmentally friendly, and had the great advantage of being able to reproduce themselves. It broke his heart to see so many healthy animals being sold either for export to the continent for meat, or going to the pet food factory. He was committed to cultivating the farm with horses. Over that first year, the stack yard at Rough Close gradually began to fill up with museum pieces of horse-drawn machinery. At farm sales no one wanted them any more, except my father. Everything went for a song, including the harness. Cleaning it was one of my jobs and I loved sitting in the quiet stable, breathing in the smell of horse mingled with harness oil.

Dad ploughing with Prince and Peter

Prince was our only shire horse, a favourite that had been with my father since he had worked as a hired lad on the farm at Raughton Head. He’d taken Prince with him to Coldslopes and then to Low Ling. Man and horse were so close Dad said that Prince could read his thoughts. The horse was so tame he would try to come into the house if the front door was left open. Once he had to be backed the whole of the length of the passageway, after he tried to follow my father into the kitchen. Now Dad had his eye out for another horse. Ploughing needed a team and there were fifty acres of neglected land at Rough Close that needed to be turned over. Peter was the first of the shires to be rescued from the slaughter house – a young horse in a very neglected state. He limped because the horn of his hooves had overgrown his shoes, one of which was missing, and his coat was rough and full of snags. Properly groomed and shod, my father decided that he would make a good team with Prince. So, we came home in the cattle wagon with fifty elderly sheep and a lame horse.

September 7, 2020

Tuesday Poem: And Then We Saw The Daughter of the Minotaur, Bob Beagrie

English poetry is blessed with fantastic poets whose work never makes the headlines. Bob Beagrie is one of them. His work has been translated into ten languages, yet his name is still less well known in the UK than it should be. I met Bob when I was the RLF Fellow at Teesside University, where he teaches creative writing. The breadth and depth of his work amazed me. His poetry is rooted in the oral, performable traditions of poetry and is often accompanied by music. Leasungspell (Smokestack 2016) is set in 7th century Northumbria and plays with Old English languages and dialect. It is 'the small tale of a nobody wandering alone through the Dark Ages', written along the faultlines where the new religion and the old magic collided, shattering linguistics and mythologies.

His work is often political. Civil Insolencies (Smokestack 2019), whose publication coincided with the Brexit debate, has its roots in the literature of the Levellers and the Royalists at the time of the English Civil War in the 17th century. It tells the story of the Battle of Guisborough, which becomes a micro-canvas where the social inequalities and injustices that drove the Civil War are played out. The parallels with twenty-first century Britain are clear.

His latest work And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur, is a sonnet sequence which is much more personal, referencing the painting by surrealist Leonora Carrington.

The sequence was written after Bob's far-too-young wife suffered a brain hemorrhage, which could have killed her, the poems are moving and compelling, from the initial dash to collect her from a railway station, to the final post-hospital reunion in the hotel where they had their honeymoon. First, he has to navigate the labyrinths of city road networks, low on fuel and his phone out of charge.

'It's about an hour's drive to York.I know the route of the tarmac maze

by heart, each intersection, slip road,

roundabout, wind and fork, clocked as I pass

in the early dark. . .'

Bob's wife has collapsed at a railway station and he brings her home where it becomes clear that she is seriously ill. She collapses again and Bob rings 999 and finds himself caught in a dark underground world of fear and grief that seems to have no way out.

The arched ceiling is adrift with grazing clouds

supported by rows of Corinthian columns,

it's surprisingly warm in the bowels of the earth.

The tunnels around us squeeze all sound

to a nugget of hard jet. I hold her hand

as we scramble over rubble, bones, leave

footprints in dust. I think the sea is above us.

I think I can hear its pulse - the ever-grind-

and-scrape of itself on its bed, restless, insatiable,

nibbling on the roots of lost cities, foregone

civilisations, there are marks on the walls

of these chambers: glyphs, pictograms, graffiti -

Please don't leave me here please don't leave

me please don't leave please don't please . . .

At the hospital, in a surreal landscape neither of them recognise, they come face to face with the female doctor, who they recognise as the Daughter of the Minotaur. She diagnoses a bleed on the brain. "Is she dying?" I enquire in silence./ "Can you name one person who isn't?" A surgeon, in the person of Theseus, expertly slays the monster lurking in the labyrinths of his wife's brain, while the poet paces rooms 'mapping their meridians,/ hang my breath on the mast like an ensign . . . the sun drowning in the insatiable sea,' and finally goes home, 'repeating the question I cannot be sure of;/ "Did I glance back as I left the labyrinth?" Finally his wife escapes, assisted by the Minotaur's daughter. She is in recovery, 'headaches, brain fatigue, but she/ is walking now, remembering . . .'

'Tomorrow we plan to drive down to the beachbeyond the field of bullocks with sad coal eyes,

climb over the dunes to spend some time with

the shifting permanence of sand, sea, wind.'In the sonnets, Bob explores some of the images in Leonora Carrington's mysterious painting, which has the quality of a dream, without meaning, but with intense resonance. We feel it in our blood, but it escapes the grasp of our minds. In painting, like poetry, you sometimes depict things you don't know you know. The images of the labyrinth and the Minotaur are deeply embedded in our cultural psyche - metaphors for the monsters that lurk in our subconscious minds. Sometimes we can't even admit to ourselves what it is that we are afraid of. Rebecca Solnit writes in The Faraway Nearby: ‘Elaborate are . . . the labyrinths in which we hide the minotaurs who have our faces’. Our greatest fear is of not being able to escape, of losing the magic thread that will show us the way out.

And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur is a beautiful sequence of poems, a pamphlet with a gloriously surreal cover by poet and artist Jane Burn. It's published by the Black Light Engine Room Press, and costs £6.00 including postage. You can message the Black Light Engine Driver here to get a copy.

Bob has also published Remnants, a collaboration with Jane Burn (Knives, Forks & Spoons Press, 2019), which plays with language, myth and magic.

He has also collaborated with northeastern poet Andy Willoughby on a number of projects including Sampo; Heading Further North, a journey in poetry and music shaped by the Scandanavian Kalevala and the rhythms of shamanic music. Both Bob and Andy have been involved in an exchange project with poets in Finland and this has been a big influence.