Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 6

August 24, 2018

Caroline's Bikini by Kirsty Gunn

It's New Zealand's National Poetry day this week, so I thought it might be fun to post a review of a new novel,

Caroline's Bikini,

by one of NZ's most prominent writers, Kirsty Gunn. She is currently Professor of Creative Writing at Dundee University and lives in Scotland. Faber sent me her new novel, which I'm reviewing for the Katherine Mansfield Society. It's a fascinating and refreshing change from much of the fiction I've seen so far this year.

Novels that involve writing about writing doesn’t usually appeal to me – maybe because, as a writer, I try to make the process as invisible as possible, just as an engineer tries to hide the workings of a building behind the elegance of its facade. Yet the process of a piece of writing is as important as the face it presents to the reader – concealing it is a literary convention.

So what do you call a novel, or a story, or a memoir that is all process, so that the process becomes the narrative – the thing itself?

The narrator, Emily Stuart (known as Nin), starts to write a novel based on a story of unrequited love told to her in a series of pubs by her childhood soul mate Evan, but she gradually realises that it is ‘veering wildly off track with every paragraph’.And, just as she is unable to recognise the relationships that are unfolding between herself, Evan and the glorious Caroline, she struggles to identify the text she is creating with her pen: ‘this essay of ours, report, genre-blending prose, whatever . . .’

This ‘work’ is not only a mesmerising account of a love triangle, it is a critique of the whole concept of narrative structure and the distinctions of genre. From the ‘meet cute’ of Evan’s encounter with Caroline in the doorway of her Richmond home, to the crisis in a pub called the Last Stand and the final (?) resolution on The Remarkable’s riverside terrace, Caroline’s Bikini challenges every cliched conception of what a novel should and shouldn’t be.

Katherine Mansfield had very decided views on the kind of fiction she wanted to write; a tantalising vision just out of reach, of something that would have perfect pitch – a type of narrative that was ‘neither a short story, nor a sketch, nor an impression, nor a tale’. Even experimental writing had to have form. ‘One cannot lightly throw one’s story over the mill.’ There were rules that must be followed. The characters must set out ‘on a voyage of discovery’, through ‘unknown seas’.

Katherine Mansfield, the only writer Virginia Woolf was afraid of!Difficulties and dangers must be encountered, ‘and there must be an ever-increasing sense of the greatness of the adventure and an ever more passionate desire to possess and explore the mysterious country’. And then there must be a crisis and a final attempt to succeed. Without this ‘central point of significance’, Mansfield insisted, ‘the form of the novel as we see it is lost’.

Katherine Mansfield, the only writer Virginia Woolf was afraid of!Difficulties and dangers must be encountered, ‘and there must be an ever-increasing sense of the greatness of the adventure and an ever more passionate desire to possess and explore the mysterious country’. And then there must be a crisis and a final attempt to succeed. Without this ‘central point of significance’, Mansfield insisted, ‘the form of the novel as we see it is lost’.

Emily Stuart, as Evan’s ‘amanuensis’, realises from the beginning that there is as yet no plot behind their story, but references Mansfield as an example of what is possible. ‘After all, there’s nothing so lively or romantic going on with Beryl in “At the Bay” either, is there,’ Emily writes, ‘that you’d think a whole dramatic story could occur from it?’ With Mansfield the reader thinks and breathes with the characters as if the author, as intermediary isn’t there. In Kirsty Gunn’s novel the workings of the author’s mind are part of the narrative. It’s the story of the writing of a story, told to the narrator by someone else (as in Wuthering Heights). But it’s clear that neither narrator nor amanuensis can be relied on when it comes to the interpretation of the facts or their own emotional condition.

One of the delicious surprises of this ‘work’, is the way that it both illustrates and subverts the history of narrative art. Virginia Woolf’s ‘moments of being’ within the story, which she compared to a ‘row of lamps’, become a series of London pubs and gin bars with significant names. Every change of location signifies a change in the emotional landscape, a shift of narrative emphasis or point of view. Even the labels of the artisan gins the characters drink are metonyms.

The narrative looks forwards, backwards, and turns itself inside out with self-analysis, in prose that is rhythmic and vivid. There are stories within stories – ‘Alternative Narratives’ with different trajectories. The chunks of ‘back story’ the writing manuals advise us to use sparingly are there in footnotes and addenda for the reader to take or leave. You leave them at your peril. The extensive research a novelist or biographer has to do, but must bury invisibly within the text (show don’t tell!) is also there so that we, as readers, can decide what is relevant and what is not.

And then there’s the question of ‘whose story is it?’. Emily thinks it’s ‘Evan’s love for Caroline . . . This is his story not mine’. The reader might have a very different viewpoint.

Kirsty GunnLiterary allusion – the background context within which we all write, woven from everything we have ever read or studied, is also there, including Mansfield and Woolf, but in particular Petrarch and the poetry of courtly love, with paradox at its heart. ‘Unrequited love,’ writes Emily, is the most ‘natural’ love of all. ‘The kind of love that seems so straightforward, so easy, honest and assured; other forms of romantic attachment seem artificial and highly wrought by comparison.’ But it is not straightforward, it is self-reflexive and repetitious, a fantasy based on emotions felt but not expressed. Evan, like other lovers so afflicted, wishes ‘to create a document, a written story or record of their desire in order that they may make real their condition’. For nothing is ‘real’ until written down. ‘How’s anyone to know anything if it’s not written down, Nin?’ Evan asks. ‘How can any of us otherwise be certain about a thing?’ .As the writing down of the story begins to consume Evan and Emily – ‘It felt like we ourselves were fading away’ – the reality of what they are actually putting into words on a page confronts them with a certainty that is both unexpected and initially unwelcome, because ‘words do happen, they can go to work on the page and wreak an effect’. P.89

Kirsty GunnLiterary allusion – the background context within which we all write, woven from everything we have ever read or studied, is also there, including Mansfield and Woolf, but in particular Petrarch and the poetry of courtly love, with paradox at its heart. ‘Unrequited love,’ writes Emily, is the most ‘natural’ love of all. ‘The kind of love that seems so straightforward, so easy, honest and assured; other forms of romantic attachment seem artificial and highly wrought by comparison.’ But it is not straightforward, it is self-reflexive and repetitious, a fantasy based on emotions felt but not expressed. Evan, like other lovers so afflicted, wishes ‘to create a document, a written story or record of their desire in order that they may make real their condition’. For nothing is ‘real’ until written down. ‘How’s anyone to know anything if it’s not written down, Nin?’ Evan asks. ‘How can any of us otherwise be certain about a thing?’ .As the writing down of the story begins to consume Evan and Emily – ‘It felt like we ourselves were fading away’ – the reality of what they are actually putting into words on a page confronts them with a certainty that is both unexpected and initially unwelcome, because ‘words do happen, they can go to work on the page and wreak an effect’. P.89

Any novel is cut from a broad cloth of almost infinite detail, as Kirsty Gunn observes in the ‘Further Material’, adding that ‘a bikini is cut, as Evan Gordonston knows, from the smallest increment of this fabric.’ Caroline’s bikini is perfectly constructed, to be consumed both literally and metaphorically. It’s a long time since I’ve read anything that excited me so much about the creative possibilities of fiction.

Kirsty Gunn Caroline's Bikini Faber 2018

Novels that involve writing about writing doesn’t usually appeal to me – maybe because, as a writer, I try to make the process as invisible as possible, just as an engineer tries to hide the workings of a building behind the elegance of its facade. Yet the process of a piece of writing is as important as the face it presents to the reader – concealing it is a literary convention.

So what do you call a novel, or a story, or a memoir that is all process, so that the process becomes the narrative – the thing itself?

The narrator, Emily Stuart (known as Nin), starts to write a novel based on a story of unrequited love told to her in a series of pubs by her childhood soul mate Evan, but she gradually realises that it is ‘veering wildly off track with every paragraph’.And, just as she is unable to recognise the relationships that are unfolding between herself, Evan and the glorious Caroline, she struggles to identify the text she is creating with her pen: ‘this essay of ours, report, genre-blending prose, whatever . . .’

This ‘work’ is not only a mesmerising account of a love triangle, it is a critique of the whole concept of narrative structure and the distinctions of genre. From the ‘meet cute’ of Evan’s encounter with Caroline in the doorway of her Richmond home, to the crisis in a pub called the Last Stand and the final (?) resolution on The Remarkable’s riverside terrace, Caroline’s Bikini challenges every cliched conception of what a novel should and shouldn’t be.

Katherine Mansfield had very decided views on the kind of fiction she wanted to write; a tantalising vision just out of reach, of something that would have perfect pitch – a type of narrative that was ‘neither a short story, nor a sketch, nor an impression, nor a tale’. Even experimental writing had to have form. ‘One cannot lightly throw one’s story over the mill.’ There were rules that must be followed. The characters must set out ‘on a voyage of discovery’, through ‘unknown seas’.

Katherine Mansfield, the only writer Virginia Woolf was afraid of!Difficulties and dangers must be encountered, ‘and there must be an ever-increasing sense of the greatness of the adventure and an ever more passionate desire to possess and explore the mysterious country’. And then there must be a crisis and a final attempt to succeed. Without this ‘central point of significance’, Mansfield insisted, ‘the form of the novel as we see it is lost’.

Katherine Mansfield, the only writer Virginia Woolf was afraid of!Difficulties and dangers must be encountered, ‘and there must be an ever-increasing sense of the greatness of the adventure and an ever more passionate desire to possess and explore the mysterious country’. And then there must be a crisis and a final attempt to succeed. Without this ‘central point of significance’, Mansfield insisted, ‘the form of the novel as we see it is lost’. Emily Stuart, as Evan’s ‘amanuensis’, realises from the beginning that there is as yet no plot behind their story, but references Mansfield as an example of what is possible. ‘After all, there’s nothing so lively or romantic going on with Beryl in “At the Bay” either, is there,’ Emily writes, ‘that you’d think a whole dramatic story could occur from it?’ With Mansfield the reader thinks and breathes with the characters as if the author, as intermediary isn’t there. In Kirsty Gunn’s novel the workings of the author’s mind are part of the narrative. It’s the story of the writing of a story, told to the narrator by someone else (as in Wuthering Heights). But it’s clear that neither narrator nor amanuensis can be relied on when it comes to the interpretation of the facts or their own emotional condition.

One of the delicious surprises of this ‘work’, is the way that it both illustrates and subverts the history of narrative art. Virginia Woolf’s ‘moments of being’ within the story, which she compared to a ‘row of lamps’, become a series of London pubs and gin bars with significant names. Every change of location signifies a change in the emotional landscape, a shift of narrative emphasis or point of view. Even the labels of the artisan gins the characters drink are metonyms.

The narrative looks forwards, backwards, and turns itself inside out with self-analysis, in prose that is rhythmic and vivid. There are stories within stories – ‘Alternative Narratives’ with different trajectories. The chunks of ‘back story’ the writing manuals advise us to use sparingly are there in footnotes and addenda for the reader to take or leave. You leave them at your peril. The extensive research a novelist or biographer has to do, but must bury invisibly within the text (show don’t tell!) is also there so that we, as readers, can decide what is relevant and what is not.

And then there’s the question of ‘whose story is it?’. Emily thinks it’s ‘Evan’s love for Caroline . . . This is his story not mine’. The reader might have a very different viewpoint.

Kirsty GunnLiterary allusion – the background context within which we all write, woven from everything we have ever read or studied, is also there, including Mansfield and Woolf, but in particular Petrarch and the poetry of courtly love, with paradox at its heart. ‘Unrequited love,’ writes Emily, is the most ‘natural’ love of all. ‘The kind of love that seems so straightforward, so easy, honest and assured; other forms of romantic attachment seem artificial and highly wrought by comparison.’ But it is not straightforward, it is self-reflexive and repetitious, a fantasy based on emotions felt but not expressed. Evan, like other lovers so afflicted, wishes ‘to create a document, a written story or record of their desire in order that they may make real their condition’. For nothing is ‘real’ until written down. ‘How’s anyone to know anything if it’s not written down, Nin?’ Evan asks. ‘How can any of us otherwise be certain about a thing?’ .As the writing down of the story begins to consume Evan and Emily – ‘It felt like we ourselves were fading away’ – the reality of what they are actually putting into words on a page confronts them with a certainty that is both unexpected and initially unwelcome, because ‘words do happen, they can go to work on the page and wreak an effect’. P.89

Kirsty GunnLiterary allusion – the background context within which we all write, woven from everything we have ever read or studied, is also there, including Mansfield and Woolf, but in particular Petrarch and the poetry of courtly love, with paradox at its heart. ‘Unrequited love,’ writes Emily, is the most ‘natural’ love of all. ‘The kind of love that seems so straightforward, so easy, honest and assured; other forms of romantic attachment seem artificial and highly wrought by comparison.’ But it is not straightforward, it is self-reflexive and repetitious, a fantasy based on emotions felt but not expressed. Evan, like other lovers so afflicted, wishes ‘to create a document, a written story or record of their desire in order that they may make real their condition’. For nothing is ‘real’ until written down. ‘How’s anyone to know anything if it’s not written down, Nin?’ Evan asks. ‘How can any of us otherwise be certain about a thing?’ .As the writing down of the story begins to consume Evan and Emily – ‘It felt like we ourselves were fading away’ – the reality of what they are actually putting into words on a page confronts them with a certainty that is both unexpected and initially unwelcome, because ‘words do happen, they can go to work on the page and wreak an effect’. P.89 Any novel is cut from a broad cloth of almost infinite detail, as Kirsty Gunn observes in the ‘Further Material’, adding that ‘a bikini is cut, as Evan Gordonston knows, from the smallest increment of this fabric.’ Caroline’s bikini is perfectly constructed, to be consumed both literally and metaphorically. It’s a long time since I’ve read anything that excited me so much about the creative possibilities of fiction.

Kirsty Gunn Caroline's Bikini Faber 2018

Published on August 24, 2018 14:46

August 20, 2018

Tuesday Poem: The XYZ of Happiness by Mary McCallum

What makes us happy? Is it an individual thing or is there a common thread for us all? These are the questions these poems try to answer. Mary McCallum is a New Zealand author, poet and publisher. Her first novel The Blue was an award winner, as was her children's book Dappled Annie and the Tigrish. She is also a prize-winning poet, founder of the Tuesday Poem network and she runs the innovative Makaro Press in Wellington. Mary's collection of poems, The XYZ of Happiness, has been eagerly awaited! This week is New Zealand's National Poetry Day, so I thought it was an appropriate time to review it.

Happiness comes in many forms - the colour yellow, gardens, a dog chasing a rabbit, familiar landscapes, family relationships, shy hellebores, music, cooking, the small simple things and the big events - love and survival. Mary draws characters with a novelist's skill; her mother with an armful of hydrangeas, Natalie, humming with life like a hive of bees, Beth, the nurse who has bad feet and a pink Fimo name badge.

The poems look backward and forwards through the whole adventure of life . . . 'We were/ whole galaxies back then - roiling, roaring, blazing in our skin'. Happiness and the sheer joy of living pervade the poetry. This is from 'Things they don't tell you on Food TV':

. . . . sun blooming in a bowl, and spooning

yoghurt and honey into a hungry mouth

on whitewashed steps with a turquoise sea

and a donkey crowing and someone calling

kalimera into the bleaching light is just like

scooping up the sun and eating it.

But the collection doesn't avoid the big questions that cast shade over all of us. At the heart of the collection is a series of poems written to Harriet Rowland who died from cancer aged just 20. Makaro Press published Harriet's searingly honest extracts from the blog she wrote about her journey from diagnosis to death in 'The Book of Hat' just before she died. Mary acknowledges that Hat "in her short fireburst of a life, showed me quite simply and clearly the XYZ of happiness".

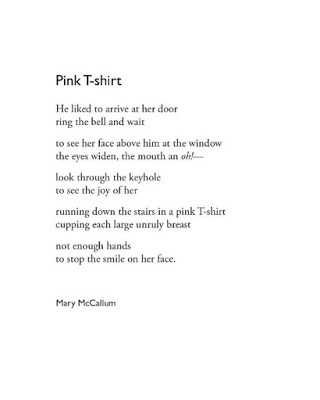

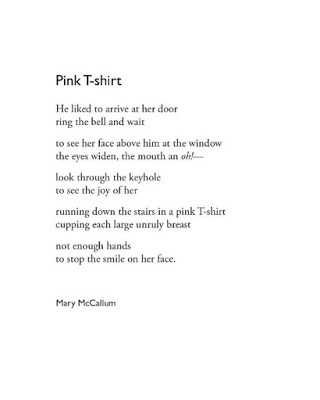

Among the thoughtful and the profound poems are little gems of delight, like the Pink T-shirt.

At a time when so many of us are depressed about the economic, political and ecological situation of the world, this collection is a blast of sunshine in a sometimes very grey landscape!

The XYZ of Happiness by Mary McCallum

Makaro Press

The XYZ of Happiness

Mary McCallum

Makaro Press

2018

Happiness comes in many forms - the colour yellow, gardens, a dog chasing a rabbit, familiar landscapes, family relationships, shy hellebores, music, cooking, the small simple things and the big events - love and survival. Mary draws characters with a novelist's skill; her mother with an armful of hydrangeas, Natalie, humming with life like a hive of bees, Beth, the nurse who has bad feet and a pink Fimo name badge.

The poems look backward and forwards through the whole adventure of life . . . 'We were/ whole galaxies back then - roiling, roaring, blazing in our skin'. Happiness and the sheer joy of living pervade the poetry. This is from 'Things they don't tell you on Food TV':

. . . . sun blooming in a bowl, and spooning

yoghurt and honey into a hungry mouth

on whitewashed steps with a turquoise sea

and a donkey crowing and someone calling

kalimera into the bleaching light is just like

scooping up the sun and eating it.

But the collection doesn't avoid the big questions that cast shade over all of us. At the heart of the collection is a series of poems written to Harriet Rowland who died from cancer aged just 20. Makaro Press published Harriet's searingly honest extracts from the blog she wrote about her journey from diagnosis to death in 'The Book of Hat' just before she died. Mary acknowledges that Hat "in her short fireburst of a life, showed me quite simply and clearly the XYZ of happiness".

Among the thoughtful and the profound poems are little gems of delight, like the Pink T-shirt.

At a time when so many of us are depressed about the economic, political and ecological situation of the world, this collection is a blast of sunshine in a sometimes very grey landscape!

The XYZ of Happiness by Mary McCallum

Makaro Press

The XYZ of Happiness

Mary McCallum

Makaro Press

2018

Published on August 20, 2018 16:30

August 19, 2018

Kathleen Raine: The Poetry Stones of Ullswater

I've just been exploring the shores of Ullswater for a workshop I'm running in September, which involves Winifred Nicholson's paintings and the work of Kathleen Raine and Norman Nicholson. The walk I've just been trying out is part of the

Ullswater Way

which stretches around the whole of the lake, though I was just doing a small part of it.

It was a typical Lake District day - cloudy, occasional sun breaking through the clouds, and a stiff breeze blowing up white caps on the water. It was a little damp, but not actually raining. We walked through the woods and had a picnic on one of the rocky promontories. Helvellyn drifted in and out of view. Bliss!

The Old Vicarage, MartindaleDuring the war Kathleen Raine lived in the remote hamlet of Martindale in the hills above Ullwater. It's not easy to get to and the Old Vicarage she lived in still has no road to the door; you have to walk across a field to get to it. It's a short walk from her house to Sandwick on the shores of Ullswater and, as a memorial to her, lines from some of the poems she wrote while she was here are carved into stones in Hallinhag wood beside the lake. The inscriptions are weathered and mossy and the stones are not easy to see among the bracken. This is what I was looking for.

The Old Vicarage, MartindaleDuring the war Kathleen Raine lived in the remote hamlet of Martindale in the hills above Ullwater. It's not easy to get to and the Old Vicarage she lived in still has no road to the door; you have to walk across a field to get to it. It's a short walk from her house to Sandwick on the shores of Ullswater and, as a memorial to her, lines from some of the poems she wrote while she was here are carved into stones in Hallinhag wood beside the lake. The inscriptions are weathered and mossy and the stones are not easy to see among the bracken. This is what I was looking for.

"human word Carved by our whispers in the passing air" from 'Night in Martindale'

"human word Carved by our whispers in the passing air" from 'Night in Martindale'

"The lake is in my dream, The tree is in my blood, The past is in my bones, The flowers of the wood I love with long past loves." from 'On Leaving Ullswater'

"The lake is in my dream, The tree is in my blood, The past is in my bones, The flowers of the wood I love with long past loves." from 'On Leaving Ullswater'

"Words say, waters flow, Rocks weather, ferns wither, winds blow, times go," from 'Night in Martindale'

"Words say, waters flow, Rocks weather, ferns wither, winds blow, times go," from 'Night in Martindale'

I'm not one of Kathleen Raine's greatest fans, though I loved her poetry as young girl. I now find much of it just too abstract and fey. But she had a significant influence on twentieth century poetry and I still rate 'Shells' (which I know by heart) as one of the poems that best describes the sense of wonder and awe generated by contact with the living world (another would be Hopkins 'Pied Beauty'). The last line 'The world that you inhabit has not yet been created', strikes now with even greater force when we live in an age that is seriously interfering with the ongoing processes of creation.

The young Kathleen Raine - a lot of men, including Norman Nicholson, fell in love with her.

The young Kathleen Raine - a lot of men, including Norman Nicholson, fell in love with her.

Kathleen Raine was part of a group of artists and poets (which also included Ben Nicholson, Percy Kelly and David Jones) spending time at a house called Cockley Moor (later owned by Fred Hoyle) which overlooks Ullswater on the other side of the lake. It was owned by Helen Sutherland, a P & O heiress and a big patron of the arts. This bringing together of painters and poets during the war years and just afterwards had a tremendous effect on all of them. But the most important part of it was the landscape they were inhabiting - Lake Ullswater and the hills around it. I'm hoping to take participants of the workshop on a walk to look at the Poetry Stones, via Martindale and the Old Vicarage.

Cockley Moor, the home of Helen Sutherland and the venue for the workshop.

Cockley Moor, the home of Helen Sutherland and the venue for the workshop.

The workshop runs all day on Saturday the 15th September. There are only a few places left. Anyone interested should contact Antoinette Fawcett through the Norman Nicholson Society. or get in touch with me via the email link on this blog.

It was a typical Lake District day - cloudy, occasional sun breaking through the clouds, and a stiff breeze blowing up white caps on the water. It was a little damp, but not actually raining. We walked through the woods and had a picnic on one of the rocky promontories. Helvellyn drifted in and out of view. Bliss!

The Old Vicarage, MartindaleDuring the war Kathleen Raine lived in the remote hamlet of Martindale in the hills above Ullwater. It's not easy to get to and the Old Vicarage she lived in still has no road to the door; you have to walk across a field to get to it. It's a short walk from her house to Sandwick on the shores of Ullswater and, as a memorial to her, lines from some of the poems she wrote while she was here are carved into stones in Hallinhag wood beside the lake. The inscriptions are weathered and mossy and the stones are not easy to see among the bracken. This is what I was looking for.

The Old Vicarage, MartindaleDuring the war Kathleen Raine lived in the remote hamlet of Martindale in the hills above Ullwater. It's not easy to get to and the Old Vicarage she lived in still has no road to the door; you have to walk across a field to get to it. It's a short walk from her house to Sandwick on the shores of Ullswater and, as a memorial to her, lines from some of the poems she wrote while she was here are carved into stones in Hallinhag wood beside the lake. The inscriptions are weathered and mossy and the stones are not easy to see among the bracken. This is what I was looking for. "human word Carved by our whispers in the passing air" from 'Night in Martindale'

"human word Carved by our whispers in the passing air" from 'Night in Martindale' "The lake is in my dream, The tree is in my blood, The past is in my bones, The flowers of the wood I love with long past loves." from 'On Leaving Ullswater'

"The lake is in my dream, The tree is in my blood, The past is in my bones, The flowers of the wood I love with long past loves." from 'On Leaving Ullswater' "Words say, waters flow, Rocks weather, ferns wither, winds blow, times go," from 'Night in Martindale'

"Words say, waters flow, Rocks weather, ferns wither, winds blow, times go," from 'Night in Martindale'I'm not one of Kathleen Raine's greatest fans, though I loved her poetry as young girl. I now find much of it just too abstract and fey. But she had a significant influence on twentieth century poetry and I still rate 'Shells' (which I know by heart) as one of the poems that best describes the sense of wonder and awe generated by contact with the living world (another would be Hopkins 'Pied Beauty'). The last line 'The world that you inhabit has not yet been created', strikes now with even greater force when we live in an age that is seriously interfering with the ongoing processes of creation.

The young Kathleen Raine - a lot of men, including Norman Nicholson, fell in love with her.

The young Kathleen Raine - a lot of men, including Norman Nicholson, fell in love with her. Kathleen Raine was part of a group of artists and poets (which also included Ben Nicholson, Percy Kelly and David Jones) spending time at a house called Cockley Moor (later owned by Fred Hoyle) which overlooks Ullswater on the other side of the lake. It was owned by Helen Sutherland, a P & O heiress and a big patron of the arts. This bringing together of painters and poets during the war years and just afterwards had a tremendous effect on all of them. But the most important part of it was the landscape they were inhabiting - Lake Ullswater and the hills around it. I'm hoping to take participants of the workshop on a walk to look at the Poetry Stones, via Martindale and the Old Vicarage.

Cockley Moor, the home of Helen Sutherland and the venue for the workshop.

Cockley Moor, the home of Helen Sutherland and the venue for the workshop.The workshop runs all day on Saturday the 15th September. There are only a few places left. Anyone interested should contact Antoinette Fawcett through the Norman Nicholson Society. or get in touch with me via the email link on this blog.

Published on August 19, 2018 06:45

August 5, 2018

August - writing in the shade

It's August, my birthday month, school and uni holidays and - in the Lake District - often one of the wettest months of the year. This year the summer so far has been hotter than a witch's cauldron and tinder dry. My office is too hot to work in, so I've migrated down to my bedroom (it's an upside down house!) which has a big window opening onto the river bank and a nice breeze blowing through.

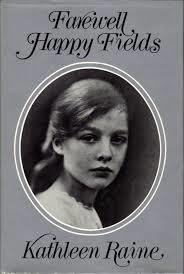

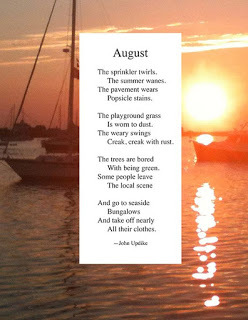

John Updike being facetiousI'm not doing much blogging or Facebooking this month - it's time for reading, relaxing (alcohol is involved here) and enjoying the smallest members of my family who come to stay. The Girl is working at a local hotel, making beds and cleaning up after tourists. Neil is in Italy (hotter than a pizza oven) house-sitting for a friend and trying to get some sculpture done. I'm copy-editing a book for the autumn, in fits and starts (mostly stops), and working on some new poems. I found the above poem by John Updike online and it immediately reminded me of Fleur Adcock's poem 'Future Work', where the poet is optimistically thinking about the summer ahead.

John Updike being facetiousI'm not doing much blogging or Facebooking this month - it's time for reading, relaxing (alcohol is involved here) and enjoying the smallest members of my family who come to stay. The Girl is working at a local hotel, making beds and cleaning up after tourists. Neil is in Italy (hotter than a pizza oven) house-sitting for a friend and trying to get some sculpture done. I'm copy-editing a book for the autumn, in fits and starts (mostly stops), and working on some new poems. I found the above poem by John Updike online and it immediately reminded me of Fleur Adcock's poem 'Future Work', where the poet is optimistically thinking about the summer ahead.

It is going to be a splendid summer.

The apple tree will be thick with golden russets

expanding weightily in the soft air.

I shall finish the brick wall beside the terrace

and plant out all the geranium cuttings.

Pinks and carnations will be everywhere.

The poet is male - there's a 'she' who tiptoes out with strawberries and jasmine tea - and there's a big ego at work. The arrogance of this assertion: -

I shall be correcting the proofs of my novel

(third in a trilogy–simultaneous publication

in four continents); and my latest play

will be in production at the Aldwych

starring Glenda Jackson and Paul Scofield

with Olivier brilliant in a minor part.

I shall probably have finished my translations

of Persian creation myths and the Pre-Socratics

(drawing new parallels) and be ready to start

on Lucretius.

But, like all of us lazing in the August sun, will anything actually happen? There's a hint of procrastination in the last lines:-

And poems? Yes, there will certainly be poems:

they sing in my head, they tingle along my nerves.

It is all magnificently about to begin.

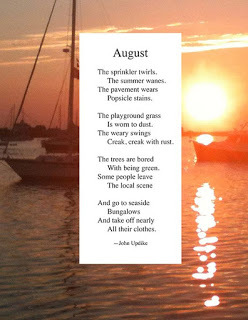

So if you don't see much of me here for the rest of the month, think of me sipping a glass of prosecco in the garden, thinking about writing. It is all, magnificently, about to begin! Here's the reading list I'm planning to enjoy in the weeks ahead:-

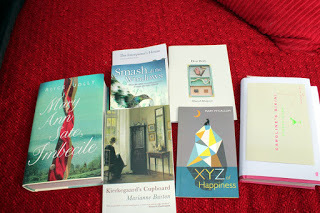

It's a blend of mainstream publishing, small press and indie, as well as a mixture of poetry and fiction - three of each, though there is some cheating involved there, which I will explain later. Mary Sate: Imbecile, by Alice Jolly, Kierkegaard's Cupboard, (poetry) by Marianne Burton, Smash all the Windows, by Jane Davis, The Interpreter's House mag, Dear Body, (poetry) by Hannah Hodgson, the XYZ of Happiness (poetry) by Mary McCallum, and Caroline's Bikini by Kirsty Gunn. Can't wait!

John Updike being facetiousI'm not doing much blogging or Facebooking this month - it's time for reading, relaxing (alcohol is involved here) and enjoying the smallest members of my family who come to stay. The Girl is working at a local hotel, making beds and cleaning up after tourists. Neil is in Italy (hotter than a pizza oven) house-sitting for a friend and trying to get some sculpture done. I'm copy-editing a book for the autumn, in fits and starts (mostly stops), and working on some new poems. I found the above poem by John Updike online and it immediately reminded me of Fleur Adcock's poem 'Future Work', where the poet is optimistically thinking about the summer ahead.

John Updike being facetiousI'm not doing much blogging or Facebooking this month - it's time for reading, relaxing (alcohol is involved here) and enjoying the smallest members of my family who come to stay. The Girl is working at a local hotel, making beds and cleaning up after tourists. Neil is in Italy (hotter than a pizza oven) house-sitting for a friend and trying to get some sculpture done. I'm copy-editing a book for the autumn, in fits and starts (mostly stops), and working on some new poems. I found the above poem by John Updike online and it immediately reminded me of Fleur Adcock's poem 'Future Work', where the poet is optimistically thinking about the summer ahead.It is going to be a splendid summer.

The apple tree will be thick with golden russets

expanding weightily in the soft air.

I shall finish the brick wall beside the terrace

and plant out all the geranium cuttings.

Pinks and carnations will be everywhere.

The poet is male - there's a 'she' who tiptoes out with strawberries and jasmine tea - and there's a big ego at work. The arrogance of this assertion: -

I shall be correcting the proofs of my novel

(third in a trilogy–simultaneous publication

in four continents); and my latest play

will be in production at the Aldwych

starring Glenda Jackson and Paul Scofield

with Olivier brilliant in a minor part.

I shall probably have finished my translations

of Persian creation myths and the Pre-Socratics

(drawing new parallels) and be ready to start

on Lucretius.

But, like all of us lazing in the August sun, will anything actually happen? There's a hint of procrastination in the last lines:-

And poems? Yes, there will certainly be poems:

they sing in my head, they tingle along my nerves.

It is all magnificently about to begin.

So if you don't see much of me here for the rest of the month, think of me sipping a glass of prosecco in the garden, thinking about writing. It is all, magnificently, about to begin! Here's the reading list I'm planning to enjoy in the weeks ahead:-

It's a blend of mainstream publishing, small press and indie, as well as a mixture of poetry and fiction - three of each, though there is some cheating involved there, which I will explain later. Mary Sate: Imbecile, by Alice Jolly, Kierkegaard's Cupboard, (poetry) by Marianne Burton, Smash all the Windows, by Jane Davis, The Interpreter's House mag, Dear Body, (poetry) by Hannah Hodgson, the XYZ of Happiness (poetry) by Mary McCallum, and Caroline's Bikini by Kirsty Gunn. Can't wait!

Published on August 05, 2018 08:52

July 23, 2018

Tuesday Poem: Editorial Statement - Kathleen Jones

‘If [what] we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow on the head,

what are we reading it for?’ Franz Kafka

I detest polite English poetry – poems you could show

to an elderly evangelical who favours censorship or

the ones you wrote about cute animals

in a workshop on Nature Poetry.

I want it with all its guts and gore

a metaphorical spectacular.

Give me fiction, faction, fireworks, ferocity, –

fierce, feminist, flamboyant – anything, but make it FEISTY.

I want commitment. Nail my brain

to the paper/ipad – or whatever I’m reading it on.

I want blood, I want extra

sensory perception.

Offend me – suspend me,

challenge my preconceived ideas to a cage fight.

I don’t care about good manners

or punctuation.

I want POETRY.

[No more than 40 lines, previously unpublished,

no simultaneous submissions]

Copyright Kathleen Jones, 2018

I don't know if anyone is following the Eyewear furore [search @eyewearbooks] but it set me thinking about poetry presses and what they're looking for. Todd Swift certainly published some innovative stuff - I either hated it or was knocked out by it - but never bored. Last week I reviewed Esther Morgan's collection 'Grace', and it made me analyse what it is I'm looking for in a poem or a novel. What would I be asking for if I was editing an anthology? I'm currently reading Kirsty Gunn's new book 'Caroline's Bikini' and it is a startling piece of fiction that defies every convention by turning them inside out without losing any kind of readability. It's mesmerising.

So I think I'm in the Kafka camp. I want enjoyment, but I also want that blow on the head - what Katherine Mansfield called the 'knock on the heart', of passion and authenticity, when I read the words.

But it's all very well asking for that as a reader, as a writer it's another struggle altogether!

what are we reading it for?’ Franz Kafka

I detest polite English poetry – poems you could show

to an elderly evangelical who favours censorship or

the ones you wrote about cute animals

in a workshop on Nature Poetry.

I want it with all its guts and gore

a metaphorical spectacular.

Give me fiction, faction, fireworks, ferocity, –

fierce, feminist, flamboyant – anything, but make it FEISTY.

I want commitment. Nail my brain

to the paper/ipad – or whatever I’m reading it on.

I want blood, I want extra

sensory perception.

Offend me – suspend me,

challenge my preconceived ideas to a cage fight.

I don’t care about good manners

or punctuation.

I want POETRY.

[No more than 40 lines, previously unpublished,

no simultaneous submissions]

Copyright Kathleen Jones, 2018

I don't know if anyone is following the Eyewear furore [search @eyewearbooks] but it set me thinking about poetry presses and what they're looking for. Todd Swift certainly published some innovative stuff - I either hated it or was knocked out by it - but never bored. Last week I reviewed Esther Morgan's collection 'Grace', and it made me analyse what it is I'm looking for in a poem or a novel. What would I be asking for if I was editing an anthology? I'm currently reading Kirsty Gunn's new book 'Caroline's Bikini' and it is a startling piece of fiction that defies every convention by turning them inside out without losing any kind of readability. It's mesmerising.

So I think I'm in the Kafka camp. I want enjoyment, but I also want that blow on the head - what Katherine Mansfield called the 'knock on the heart', of passion and authenticity, when I read the words.

But it's all very well asking for that as a reader, as a writer it's another struggle altogether!

Published on July 23, 2018 16:30

July 17, 2018

Tuesday Poem: This Morning by Esther Morgan

I watched the sun moving round the kitchen,

an early spring sun that strengthened and weakened,

coming and going like an old mind.

I watched like one bedridden for a long time

on their first journey back into the world

who finds it enough to be going on with:

the way the sunlight brought each possession in turn

to its attention and made of it a small still life:

the iron frying pan gleaming on its hook like an ancient find,

the powdery green cheek of a bruised clementine.

Though more beautiful still was how the light moved on,

letting go each chair and coffee cup without regret

the way my grandmother, in her final year, received me:

neither surprised by my presence, nor distressed by my leaving,

content, though, while I was there.

© 2010, Esther Morgan

Bridport Prize-winner, 2010

From: Grace

Publisher: Bloodaxe Books, 2011

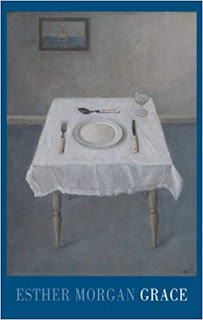

Everyone complains about Facebook, but without it I'd miss a lot of good reading. One of my FB friends mentioned Esther Morgan with such enthusiasm I set off to find her. I bought Grace second hand (sorry!) and sat up half the night reading it. How could I have missed such a good poet? These are poems that are both delicate and strong. There are lines I would kill for. Seamus Heaney once said that poetry is not a gift, or a craft, but a 'grace' and there is an echo of that in the title, though the cover image suggests something more conventional.

The poetry contains a darker message - 'what we may be about to receive' when we spread our lives 'out like a cloth' may not be quite what we want or expect. The title poem brings to life 'the moment the house empties like a city in August' and that watchful stillness that feels like a prelude:

... simple, though not easy this waiting without hunger in the near dark for what you may be about to receive.

Alison Brackenbury, reviewing Grace wrote: 'Esther Morgan's third collection, is an extraordinary, radiant book. Its poetry makes quietly insistent demands upon the reader: "In the stillness, everything becomes itself."... The afterglow of Esther Morgan's luminous work is not certainty, but questions. Can imagination transform, or simply recognise, what is there? Do these poems come by grace of Muse or angel?’ – Alison Brackenbury, Poetry London.

This quiet, contemplative 'register' of poetry, like that of Mary Oliver's, is not always to my taste - I tend to go for something bolder, salty rather than sweet, but Grace surprised me (as Oliver sometimes does) by achieving a real complexity - a kind of gourmet morsel on the tongue, whose flavour you can't quite identify, that leaves you wanting more.

Esther Morgan's new collection (the first in 7 years) is called The Wound Register , a title taken from the official record of the casualty and sickness details for more than fifteen thousand soldiers of the Norfolk Regiment during the First World War. Released presumably to celebrate the centenary of WWI, the poems apparently: "apply the concept to her own family history in the aftermath of her great-grandfather’s death at the Somme." It contains, according to the blurb, "an unflinching sequence written to her grandmother which explores the trauma of losing a father in combat, while other poems address the missing soldier directly as he hovers on the brink of living memory". I'm definitely going to be seeking this out.

Esther Morgan, Bloodaxe Poets

The Wound Register, Bloodaxe, 2018

Grace, Bloodaxe 2011

Published on July 17, 2018 08:00

July 16, 2018

This Never-ending Summer

Here in the north we're not used to it. 'Four seasons in one day', the saying goes and it's usually true. But this year . . . I can go out without taking a coat or an umbrella. I can wear clothes suitable for a Mediterranean holiday. We plan picnics and barbecues without bothering to have a Plan B. And the summer goes on and on and on.

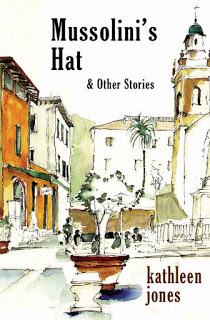

The Girl and The Butterfly - it's that kind of summerMy writing room is in the roof under the slates, with two big skylights. It's been like Death Valley by mid-day even with a fan. Hot air stirred is still hot. I'm trying to edit a book, but it's not going well. The collection of stories I'm working on is set in Italy, so I should feel quite at home! This collection is quite tricky because the 12 stories aren't quite stand-alone - the sub-title is '12 people, 12 stories, a year in the life of a small Italian town'. There are 12 main characters and the action takes place in the Piazza across 12 months. They each have their own story, but they also walk in and out of each other's. And there's a chorus of Beautiful Girls and Albanian Boys. Whether it works or not, I don't know. But these stories are based on my two decades of Italian experience, particularly the 3 years I spent living there rather than just visiting, and the hours I spent in the Piazza, watching people. It's one of my favourite occupations.

The Girl and The Butterfly - it's that kind of summerMy writing room is in the roof under the slates, with two big skylights. It's been like Death Valley by mid-day even with a fan. Hot air stirred is still hot. I'm trying to edit a book, but it's not going well. The collection of stories I'm working on is set in Italy, so I should feel quite at home! This collection is quite tricky because the 12 stories aren't quite stand-alone - the sub-title is '12 people, 12 stories, a year in the life of a small Italian town'. There are 12 main characters and the action takes place in the Piazza across 12 months. They each have their own story, but they also walk in and out of each other's. And there's a chorus of Beautiful Girls and Albanian Boys. Whether it works or not, I don't know. But these stories are based on my two decades of Italian experience, particularly the 3 years I spent living there rather than just visiting, and the hours I spent in the Piazza, watching people. It's one of my favourite occupations.

The life of a writer is very odd, because it has so many different facets. There's research (which can be almost anything you do!), actual writing of words, editing, proof-reading, publicity, public events such as talks and book-signings, running writer's workshops, reading groups, attending conferences, going to business meetings with publishers and agents, struggling with accounts, hawking your books around book shops, and swanning around at literary award 'do's' in a posh frock. It must be one of the most fragmentary occupations on earth - not so much a job as a way of life.

In the last month I've been to two conferences related to books I've written and a literary award ceremony to cheer on friends who'd been nominated. I managed to win a bottle of champagne in a raffle, which is currently chilling in the fridge waiting for an excuse! The reading group I've been running for 3 years came to an end last week and it was a very sad parting of the ways. I was very touched to be given cards and flowers and presents - they were a terrific group. Writers need readers and they were the best.

Behind the scenes is the quiet struggle to maintain family life and still have enough time to write the stuff that's bursting to get out. I have a partner and a teenager who need to be reminded that I exist now and then. Friends need to be cooked and catered for. This week we had two friends from Italy to stay - lovely meals, days out in the Lake District and lots of wine.

This week I'm in London to help Neil deliver a sculpture to an exhibition and then down to Kent to watch 2 little granddaughters dance in a ballet show. I'm exhausted just describing it all. Perhaps I should just give up writing and go and lie in the garden in the sun!

The Girl and The Butterfly - it's that kind of summerMy writing room is in the roof under the slates, with two big skylights. It's been like Death Valley by mid-day even with a fan. Hot air stirred is still hot. I'm trying to edit a book, but it's not going well. The collection of stories I'm working on is set in Italy, so I should feel quite at home! This collection is quite tricky because the 12 stories aren't quite stand-alone - the sub-title is '12 people, 12 stories, a year in the life of a small Italian town'. There are 12 main characters and the action takes place in the Piazza across 12 months. They each have their own story, but they also walk in and out of each other's. And there's a chorus of Beautiful Girls and Albanian Boys. Whether it works or not, I don't know. But these stories are based on my two decades of Italian experience, particularly the 3 years I spent living there rather than just visiting, and the hours I spent in the Piazza, watching people. It's one of my favourite occupations.

The Girl and The Butterfly - it's that kind of summerMy writing room is in the roof under the slates, with two big skylights. It's been like Death Valley by mid-day even with a fan. Hot air stirred is still hot. I'm trying to edit a book, but it's not going well. The collection of stories I'm working on is set in Italy, so I should feel quite at home! This collection is quite tricky because the 12 stories aren't quite stand-alone - the sub-title is '12 people, 12 stories, a year in the life of a small Italian town'. There are 12 main characters and the action takes place in the Piazza across 12 months. They each have their own story, but they also walk in and out of each other's. And there's a chorus of Beautiful Girls and Albanian Boys. Whether it works or not, I don't know. But these stories are based on my two decades of Italian experience, particularly the 3 years I spent living there rather than just visiting, and the hours I spent in the Piazza, watching people. It's one of my favourite occupations.

The life of a writer is very odd, because it has so many different facets. There's research (which can be almost anything you do!), actual writing of words, editing, proof-reading, publicity, public events such as talks and book-signings, running writer's workshops, reading groups, attending conferences, going to business meetings with publishers and agents, struggling with accounts, hawking your books around book shops, and swanning around at literary award 'do's' in a posh frock. It must be one of the most fragmentary occupations on earth - not so much a job as a way of life.

In the last month I've been to two conferences related to books I've written and a literary award ceremony to cheer on friends who'd been nominated. I managed to win a bottle of champagne in a raffle, which is currently chilling in the fridge waiting for an excuse! The reading group I've been running for 3 years came to an end last week and it was a very sad parting of the ways. I was very touched to be given cards and flowers and presents - they were a terrific group. Writers need readers and they were the best.

Behind the scenes is the quiet struggle to maintain family life and still have enough time to write the stuff that's bursting to get out. I have a partner and a teenager who need to be reminded that I exist now and then. Friends need to be cooked and catered for. This week we had two friends from Italy to stay - lovely meals, days out in the Lake District and lots of wine.

This week I'm in London to help Neil deliver a sculpture to an exhibition and then down to Kent to watch 2 little granddaughters dance in a ballet show. I'm exhausted just describing it all. Perhaps I should just give up writing and go and lie in the garden in the sun!

Published on July 16, 2018 02:56

July 12, 2018

Tales from the River Bank - Drought and Danger

Like most of the country, up here in the Lake District we've been experiencing record high temperatures and one of the longest dry spells we've ever had. It's the Lake District - it rains! But not this year. The Jet Stream has gone adrift and is pouring the stuff over Iceland instead. Here at the Mill we've only had one shower in more than 9 weeks. The river is lower than I've ever seen it and the mill pond is murky and full of algae.

The garden has been hit hard too, though I'm managing to keep it going. The hot dry conditions seem to suit some of the plants - this Tuscany Superb managed to survive Storm Desmond (just) but is now thriving in Italian weather.

But the old weir is not surviving so well. It's a very ancient, historic structure. Apparently there was a weir of some kind here in Roman times. It's a beautiful stretch of water that provides an opportunity for all the local kids to swim and paddle canoes and generally enjoy themselves. But the River Authority has closed it in the last couple of days. There's a notice saying that it's an 'unstable structure'.

A sink hole appeared where the salmon leap is in the centre of the weir, taking a lot of water down and underneath instead of over the waterfall. It got progressively bigger and more powerful and so the River Authority have piled rocks in as a temporary measure. They will wash out again with the first rains.

This is all very worrying for us. Storm Desmond obviously did some damage, old age is taking its toll and the present heat has been enough to bend the steel bars that hold the stones together. The heat and the drought are cracking the concrete put in to repair the weir 18 years ago. There are cracks you can put your hand in - cracks that will let the water through when the level rises again and allow the river to break up the structure even more.

There are already some very big holes where previous repairs have failed.

What is the answer? With so little public money available I don't think anyone can justify spending the million or two you'd need to restore the weir. Particularly as it no longer has a purpose. Its day has gone. Perhaps we should just let it decay naturally into the surroundings and let the mimulus and the alder and the wild irises take over to create something more beautiful? What do others think?

The garden has been hit hard too, though I'm managing to keep it going. The hot dry conditions seem to suit some of the plants - this Tuscany Superb managed to survive Storm Desmond (just) but is now thriving in Italian weather.

But the old weir is not surviving so well. It's a very ancient, historic structure. Apparently there was a weir of some kind here in Roman times. It's a beautiful stretch of water that provides an opportunity for all the local kids to swim and paddle canoes and generally enjoy themselves. But the River Authority has closed it in the last couple of days. There's a notice saying that it's an 'unstable structure'.

A sink hole appeared where the salmon leap is in the centre of the weir, taking a lot of water down and underneath instead of over the waterfall. It got progressively bigger and more powerful and so the River Authority have piled rocks in as a temporary measure. They will wash out again with the first rains.

This is all very worrying for us. Storm Desmond obviously did some damage, old age is taking its toll and the present heat has been enough to bend the steel bars that hold the stones together. The heat and the drought are cracking the concrete put in to repair the weir 18 years ago. There are cracks you can put your hand in - cracks that will let the water through when the level rises again and allow the river to break up the structure even more.

There are already some very big holes where previous repairs have failed.

What is the answer? With so little public money available I don't think anyone can justify spending the million or two you'd need to restore the weir. Particularly as it no longer has a purpose. Its day has gone. Perhaps we should just let it decay naturally into the surroundings and let the mimulus and the alder and the wild irises take over to create something more beautiful? What do others think?

Published on July 12, 2018 15:18

July 2, 2018

The Strange World of Literary Societies and Dead Authors

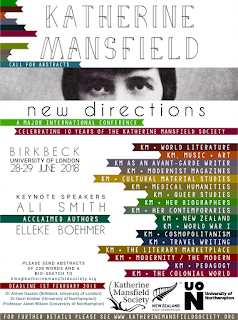

I've just come back from a few very enjoyable days discussing the life and work of Katherine Mansfield at London University, a conference organised by the

Katherine Mansfield Society

.

The one thing you don't think about when you're a writer, is the possibility that someone might want to set up a literary society to remember you when you're dead!

The Australian poet Dorothy Porter (who died prematurely in 2008) once wrote that 'the book of the dead author is a haunted house'. The house contains forgotten conversations, scraps of clothing, a few letters, undecipherable notes, the flawed memories of friends (who are possibly other dead authors), a flock of biographies, academic papers and a lot of divergent opinions. It's a strange place to be.

Most famous authors have one - there's a Coleridge Society, a Hardy Society, Virginia Woolf has one, and so do Philip Larkin, Norman Nicholson, and Sylvia Plath - there's even an Association of Literary Societies so that you can all meet up and talk about your dead author's literary society!

10 years ago the Katherine Mansfield Society was formed - (roughly 90 years after her death from TB at Fontainebleau in 1923) - after the very first conference at London university. I remember because I was one of the speakers and we all had dinner afterwards in the Ambassador's penthouse at New Zealand House. The view across London was spectacular and the wine was pretty good too - but luckily the railings were high enough to prevent accidents!

The Life Writing Panel, novelist Kirsten Ellis, poet Anna Jackson and myselfThe society is still going strong and some of the meetings have been very exotic - there have been conferences in Slovakia, Menton and Bandol in the south of France, Melbourne Oz, Chicago USA, Montana Switzerland, Wellington NZ and now back to London again. All these places had some link to KM. It has been a journey through her life and the archives of material she left behind.

The Life Writing Panel, novelist Kirsten Ellis, poet Anna Jackson and myselfThe society is still going strong and some of the meetings have been very exotic - there have been conferences in Slovakia, Menton and Bandol in the south of France, Melbourne Oz, Chicago USA, Montana Switzerland, Wellington NZ and now back to London again. All these places had some link to KM. It has been a journey through her life and the archives of material she left behind.

A writer's reputation is often 'owned' by the society, which in some cases can become a kind of mafia protecting the writer's reputation at the risk of extinguishing it. Fortunately that's not the case with Katherine Mansfield - it's more like a family and part of the joy of attending is meeting friends one has made through it. There are always more - this time Holly, who invited me to a dinner at Christchurch University in NZ, and Huang Qiang, who I met when he was a PhD candidate at Lancaster University where I was the RLF Fellow. Qiang is now a lecturer at the University of Beijing - Holly is just about to graduate. What we all share is a passion for Katherine Mansfield.

Huang Qiang and me!

Huang Qiang and me!

Ali Smith gave the first keynote speech and is as wonderful in person as she is on the page; Kirsty Gunn was there and is now the new Patron of the Society, Dame Jacqueline Wilson having retired. London shimmered with heat while we lurked in the air conditioned basement, emerging only in the evening to more conversations over wine and food in the bars and restaurants around Bloomsbury.

It isn't all work! (Photo Gerri Kimber)

It isn't all work! (Photo Gerri Kimber)

If you don't think we have a good time, this is us having a sing song i n several languages in the Antalya off Russell Square. (thanks to Lei Yuemei!) I've come home exhausted, but full of ideas!

If you love Katherine Mansfield, why not like her Facebook Page?

Or buy some books?

Katherine Mansfield: The Storyteller by Kathleen Jones (paperback £12.15, e-book £3.32)

Katherine Mansfield: The Early Years by Gerri Kimber

A Strange, Beautiful Excitement by Redmer Yska

The one thing you don't think about when you're a writer, is the possibility that someone might want to set up a literary society to remember you when you're dead!

The Australian poet Dorothy Porter (who died prematurely in 2008) once wrote that 'the book of the dead author is a haunted house'. The house contains forgotten conversations, scraps of clothing, a few letters, undecipherable notes, the flawed memories of friends (who are possibly other dead authors), a flock of biographies, academic papers and a lot of divergent opinions. It's a strange place to be.

Most famous authors have one - there's a Coleridge Society, a Hardy Society, Virginia Woolf has one, and so do Philip Larkin, Norman Nicholson, and Sylvia Plath - there's even an Association of Literary Societies so that you can all meet up and talk about your dead author's literary society!

10 years ago the Katherine Mansfield Society was formed - (roughly 90 years after her death from TB at Fontainebleau in 1923) - after the very first conference at London university. I remember because I was one of the speakers and we all had dinner afterwards in the Ambassador's penthouse at New Zealand House. The view across London was spectacular and the wine was pretty good too - but luckily the railings were high enough to prevent accidents!

The Life Writing Panel, novelist Kirsten Ellis, poet Anna Jackson and myselfThe society is still going strong and some of the meetings have been very exotic - there have been conferences in Slovakia, Menton and Bandol in the south of France, Melbourne Oz, Chicago USA, Montana Switzerland, Wellington NZ and now back to London again. All these places had some link to KM. It has been a journey through her life and the archives of material she left behind.

The Life Writing Panel, novelist Kirsten Ellis, poet Anna Jackson and myselfThe society is still going strong and some of the meetings have been very exotic - there have been conferences in Slovakia, Menton and Bandol in the south of France, Melbourne Oz, Chicago USA, Montana Switzerland, Wellington NZ and now back to London again. All these places had some link to KM. It has been a journey through her life and the archives of material she left behind.A writer's reputation is often 'owned' by the society, which in some cases can become a kind of mafia protecting the writer's reputation at the risk of extinguishing it. Fortunately that's not the case with Katherine Mansfield - it's more like a family and part of the joy of attending is meeting friends one has made through it. There are always more - this time Holly, who invited me to a dinner at Christchurch University in NZ, and Huang Qiang, who I met when he was a PhD candidate at Lancaster University where I was the RLF Fellow. Qiang is now a lecturer at the University of Beijing - Holly is just about to graduate. What we all share is a passion for Katherine Mansfield.

Huang Qiang and me!

Huang Qiang and me!Ali Smith gave the first keynote speech and is as wonderful in person as she is on the page; Kirsty Gunn was there and is now the new Patron of the Society, Dame Jacqueline Wilson having retired. London shimmered with heat while we lurked in the air conditioned basement, emerging only in the evening to more conversations over wine and food in the bars and restaurants around Bloomsbury.

It isn't all work! (Photo Gerri Kimber)

It isn't all work! (Photo Gerri Kimber)If you don't think we have a good time, this is us having a sing song i n several languages in the Antalya off Russell Square. (thanks to Lei Yuemei!) I've come home exhausted, but full of ideas!

If you love Katherine Mansfield, why not like her Facebook Page?

Or buy some books?

Katherine Mansfield: The Storyteller by Kathleen Jones (paperback £12.15, e-book £3.32)

Katherine Mansfield: The Early Years by Gerri Kimber

A Strange, Beautiful Excitement by Redmer Yska

Published on July 02, 2018 06:54

June 18, 2018

Tuesday Poem: W.H. Auden - 1st September 1939

I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade;

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god;

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief;

We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each landscape pours its vain

Competitive excuse;

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism's face

And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day;

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish;

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come,

Repeating their morning vow;

'I will be true to the wife,

I'll concentrate more on my work,'

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game;

Who can release them now,

Who can reach the deaf

Who can speak for the dumb?

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet dotted everywhere

Ironic point of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages;

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

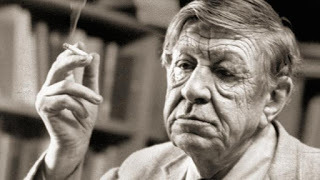

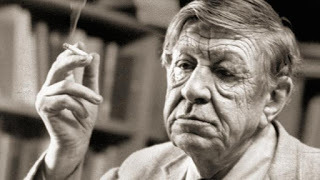

W.H. Auden

I've been re-reading Auden and find him rather wordy and ponderous at times, but there were poems that struck to the bone and this is one of them. I felt that it could have been written for now - this 'low, dishonest decade', with a psychopathic god conjured out of the bible by dictators, in a 'euphoric dream' spouting their 'competitive excuses'. We are indeed children 'lost in a haunted wood'.

Apparently in some of the lines he was referring back to W.B. Yeats 'Easter 1916'* - another powerful commentary on the slide into political upheaval - and I don't find it surprising that New Yorkers turned to this poem when the Twin Towers came down in 2001 and the 'strength of Collective Man' was challenged. The moment felt - and was - apocalyptic. The world as we knew it was never the same again afterwards - not just politically, but in that our own personal freedoms were curtailed - even the laws that protected us from imprisonment without trial and the unjust uses of state power were limited or removed under the excuse of terrorism.

Auden had one of the most lived-in faces I have ever seen - a tribute to a life lived to the full, though it was often tragic. He was born and educated in England but moved to America in 1939. He spent time in Berlin, had a relationship (and wrote 3 plays) with Christopher Isherwood. In 1935 he married Erika Mann purely to give her British nationality to escape the Nazis. The marriage was never consummated. His relationships with men were often painful - his intense love, and desire for a long-term relationship, often unrequited.

A young and handsome Auden with his lover Christopher Isherwood in 1939Politically Auden was left-wing - he went to Spain intending to drive an ambulance in the Spanish Civil War, only to become a journalist instead. The experiences he had in Berlin and Spain influenced his writing for the rest of his life. He was deeply intellectual - Joseph Brodsky said that he had the 'greatest mind' of his generation. As a writer he was very versatile, writing prose and poetry and collaborating with Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky on opera libretto. He died in 1973 after a poetry reading in Vienna.

A young and handsome Auden with his lover Christopher Isherwood in 1939Politically Auden was left-wing - he went to Spain intending to drive an ambulance in the Spanish Civil War, only to become a journalist instead. The experiences he had in Berlin and Spain influenced his writing for the rest of his life. He was deeply intellectual - Joseph Brodsky said that he had the 'greatest mind' of his generation. As a writer he was very versatile, writing prose and poetry and collaborating with Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky on opera libretto. He died in 1973 after a poetry reading in Vienna.

I'm keeping an open mind as I re-read. There are conflicting opinions on Auden's work and he is no longer revered as one of the 'men of letters' who were so influential during the thirties and forties. Ironically, he's now best known for his poem 'Funeral Blues' read in the film 'Four Weddings and a Funeral'. It started out as a satirical poem in a play about a corrupt politician, was set to music for a cabaret by Benjamin Britten, but what was written as mockery and melodrama is now taken as a straight expression of grief. How things change!

* In Auden's collection, '1st September 1939' follows directly after his poem 'In Memory of W.B. Yeats'.

If you don't want to buy the bulky 'Collected Poems', this might be a good choice. You can pick up second hand copies quite cheaply.

W.H. Auden, ed. John Fuller

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade;

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night.

Accurate scholarship can

Unearth the whole offence

From Luther until now

That has driven a culture mad,

Find what occurred at Linz,

What huge imago made

A psychopathic god;

I and the public know

What all schoolchildren learn,

Those to whom evil is done

Do evil in return.

Exiled Thucydides knew

All that a speech can say

About Democracy,

And what dictators do,

The elderly rubbish they talk

To an apathetic grave;

Analysed all in his book,

The enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief;

We must suffer them all again.

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man,

Each landscape pours its vain

Competitive excuse;

But who can live for long

In an euphoric dream;

Out of the mirror they stare,

Imperialism's face

And the international wrong.

Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day;

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.

The windiest militant trash

Important Persons shout

Is not so crude as our wish;

What mad Nijinsky wrote

About Diaghilev

Is true of the normal heart;

For the error bred in the bone

Of each woman and each man

Craves what it cannot have,

Not universal love

But to be loved alone.

From the conservative dark

Into the ethical life

The dense commuters come,

Repeating their morning vow;

'I will be true to the wife,

I'll concentrate more on my work,'

And helpless governors wake

To resume their compulsory game;

Who can release them now,

Who can reach the deaf

Who can speak for the dumb?

Defenceless under the night

Our world in stupor lies;

Yet dotted everywhere

Ironic point of light

Flash out wherever the Just

Exchange their messages;

May I, composed like them

Of Eros and of dust,

Beleaguered by the same

Negation and despair,

Show an affirming flame.

W.H. Auden

I've been re-reading Auden and find him rather wordy and ponderous at times, but there were poems that struck to the bone and this is one of them. I felt that it could have been written for now - this 'low, dishonest decade', with a psychopathic god conjured out of the bible by dictators, in a 'euphoric dream' spouting their 'competitive excuses'. We are indeed children 'lost in a haunted wood'.

Apparently in some of the lines he was referring back to W.B. Yeats 'Easter 1916'* - another powerful commentary on the slide into political upheaval - and I don't find it surprising that New Yorkers turned to this poem when the Twin Towers came down in 2001 and the 'strength of Collective Man' was challenged. The moment felt - and was - apocalyptic. The world as we knew it was never the same again afterwards - not just politically, but in that our own personal freedoms were curtailed - even the laws that protected us from imprisonment without trial and the unjust uses of state power were limited or removed under the excuse of terrorism.

Auden had one of the most lived-in faces I have ever seen - a tribute to a life lived to the full, though it was often tragic. He was born and educated in England but moved to America in 1939. He spent time in Berlin, had a relationship (and wrote 3 plays) with Christopher Isherwood. In 1935 he married Erika Mann purely to give her British nationality to escape the Nazis. The marriage was never consummated. His relationships with men were often painful - his intense love, and desire for a long-term relationship, often unrequited.

A young and handsome Auden with his lover Christopher Isherwood in 1939Politically Auden was left-wing - he went to Spain intending to drive an ambulance in the Spanish Civil War, only to become a journalist instead. The experiences he had in Berlin and Spain influenced his writing for the rest of his life. He was deeply intellectual - Joseph Brodsky said that he had the 'greatest mind' of his generation. As a writer he was very versatile, writing prose and poetry and collaborating with Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky on opera libretto. He died in 1973 after a poetry reading in Vienna.

A young and handsome Auden with his lover Christopher Isherwood in 1939Politically Auden was left-wing - he went to Spain intending to drive an ambulance in the Spanish Civil War, only to become a journalist instead. The experiences he had in Berlin and Spain influenced his writing for the rest of his life. He was deeply intellectual - Joseph Brodsky said that he had the 'greatest mind' of his generation. As a writer he was very versatile, writing prose and poetry and collaborating with Benjamin Britten and Igor Stravinsky on opera libretto. He died in 1973 after a poetry reading in Vienna.I'm keeping an open mind as I re-read. There are conflicting opinions on Auden's work and he is no longer revered as one of the 'men of letters' who were so influential during the thirties and forties. Ironically, he's now best known for his poem 'Funeral Blues' read in the film 'Four Weddings and a Funeral'. It started out as a satirical poem in a play about a corrupt politician, was set to music for a cabaret by Benjamin Britten, but what was written as mockery and melodrama is now taken as a straight expression of grief. How things change!

* In Auden's collection, '1st September 1939' follows directly after his poem 'In Memory of W.B. Yeats'.

If you don't want to buy the bulky 'Collected Poems', this might be a good choice. You can pick up second hand copies quite cheaply.

W.H. Auden, ed. John Fuller

Published on June 18, 2018 16:30