Kathleen Jones's Blog, page 10

October 23, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Teacher Man - by Steve Ely

The first day, Shane told him to fuck off

and punched Dominic in the head before

slamming out of the classroom.

The second day, Joe Rowton asked him

if he was gay, 8B6 practised wrestling moves,

year eleven bombed him with screwed-up worksheets.

The third day, his classes ignored him completely

and just continued their conversations.

Zoe erupted in a screaming fit and bowled chairs

across the classroom. He wrote out his resignation.

The fourth day, he left the envelope

on the mantel and gave it one more chance.

Shane squared up to Dylan and somehow

smashed his laptop.

The fifth day, he took the envelope into school

and turned it in his hands all morning.

Shane tore up Kai's work but wrote a half-page himself.

Joe Rowton read 'Hitcher' and deemed

the poem mint. Zoe mastered the punctuation

of direct speech: "I'm off to the bog

and you can't stop me cos I'm on my period."

He took the envelope home and on Friday night

got hammered. Saturday and Sunday

he worked all day. One more week.

On the one hundred and ninety-fifth day,

Shane threw a water-bomb. Joe Rowton read out

his five-hundred-word essay on karting.

8B6 got certificates and Zoe stayed behind

and told him, "Why can't we have you next year, Sir?

You're a laugh, we learn things with you."

Six weeks on the beach my arse: schemes of work

and lesson plans; a fortnight teaching summer school;

and a half-day at the Magistrates, with Shane

and his weeping mother; he'd swiped SpongeBob socks

from Primark 'because his feet were cold'.

He put in a good word.

The first day back, Shane told him Lee Darby

had brought in a flick knife and Joe Rowton

had got Zoe pregnant: but don't tell no one

you got it from me.

Copyright Steve Ely

from Werewolf, published by Calder Valley Poetry 2016

This poem made me want to laugh and cry at the same time. It captures so graphically the realities of teaching for so many teachers. And it reminded me of a residency I had in a school where the staff barricaded themselves in the staff room at break and ignored all extraneous noises until it was time to venture out again. Only the head was brave enough to park his car in the school car park. As the writer in residence I often got treated as a free babysitter. I was abandoned on a Friday afternoon with year 11XX by a teacher who grinned wolfishly before declaring a dentist's appointment and scarpering. Several of the students disappeared shortly afterwards and some of the others began practising basket ball with the light fitting over the blackboard. Creative Writing? It was a free-for-all. But one of the students came up at the end and asked for my autograph. I must have looked puzzled because he added 'Just in case you get famous!' I could never have been a school teacher.

It was a Yorkshire poet Bob Horne who introduced me to Steve Ely's poetry at a writers' retreat. I bought the Calder Valley Poetry pamphlet last year and I'm still reading it. Werewolf is a dark collection that looks at the world and records its tragi-comic realities without softening the message that we are a violent, deceitful species. 'Every Child Matters' begins:

not really

we profess to believe it but our actions say otherwise

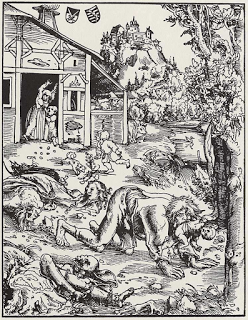

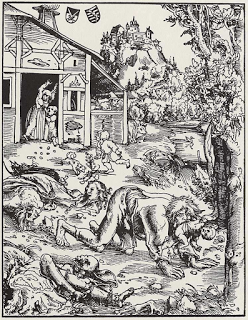

'Werewolf' - Lucas Cranach the Elder

'Werewolf' - Lucas Cranach the Elder

'The Death Dealer of Kovno' deals with the 1941 Jewish massacre in Lithuania. The poetry is compelling, even when the subject matter appalls. Peter Riley describes the collection as 'this narrative catalogue of the capacity for human harm' which 'becomes a song/story book that grips, fascinates and in a grim kind of way, delights.' Which is exactly how it feels.

All our moral 'givens' are questioned. We think we are morally superior? That concentration camps couldn't exist in the UK? No. Even the worst could happen here. In 'Spurn'

Once the decision was made

it was simply a matter of logistics.

Trains from ghettos all over the country

dropped their freight at Doncaster sidings,

where tantalising tastes of Southern Fried Chicken

licked around the cars

like tongues of heavenly vipers.

In the mythologies of the poetry, the Tigers of Tigerland, happy to co-exist ('Tigerland was a broad land and there was room enough for all.') are at first welcoming when the White Men arrive. But soon there are no more Tiger people - only a colonial folk tale of savage beasts who 'came howling from the hills like savages, raping women and slaughtering children, until Providence snuffed them out.'

Male violence in particular is put under interrogation. In a year that has seen the revelations of Trump and Weinstein, massacres in the US and Europe, and the horrors of ethnic violence in Yemen and Myanmar the poetry is both a dark mirror held up to ourselves and an honest reflection of the world beyond the page. It emphasises the fragility of our own, illusory, safety. The poetry is astonishing, both technically and linguistically. I'm still reeling from its impact.

Steve Ely is the author of a novel Ratmen (Blackheath Books), a biography - Ted Hughes's South Yorkshire (Palgrave MacMillan), and two other collections of poetry - Englaland and Oswald's Book of Hours, both from Smokestack.

Werewolf is £7.00 from Calder Valley Poetry

and punched Dominic in the head before

slamming out of the classroom.

The second day, Joe Rowton asked him

if he was gay, 8B6 practised wrestling moves,

year eleven bombed him with screwed-up worksheets.

The third day, his classes ignored him completely

and just continued their conversations.

Zoe erupted in a screaming fit and bowled chairs

across the classroom. He wrote out his resignation.

The fourth day, he left the envelope

on the mantel and gave it one more chance.

Shane squared up to Dylan and somehow

smashed his laptop.

The fifth day, he took the envelope into school

and turned it in his hands all morning.

Shane tore up Kai's work but wrote a half-page himself.

Joe Rowton read 'Hitcher' and deemed

the poem mint. Zoe mastered the punctuation

of direct speech: "I'm off to the bog

and you can't stop me cos I'm on my period."

He took the envelope home and on Friday night

got hammered. Saturday and Sunday

he worked all day. One more week.

On the one hundred and ninety-fifth day,

Shane threw a water-bomb. Joe Rowton read out

his five-hundred-word essay on karting.

8B6 got certificates and Zoe stayed behind

and told him, "Why can't we have you next year, Sir?

You're a laugh, we learn things with you."

Six weeks on the beach my arse: schemes of work

and lesson plans; a fortnight teaching summer school;

and a half-day at the Magistrates, with Shane

and his weeping mother; he'd swiped SpongeBob socks

from Primark 'because his feet were cold'.

He put in a good word.

The first day back, Shane told him Lee Darby

had brought in a flick knife and Joe Rowton

had got Zoe pregnant: but don't tell no one

you got it from me.

Copyright Steve Ely

from Werewolf, published by Calder Valley Poetry 2016

This poem made me want to laugh and cry at the same time. It captures so graphically the realities of teaching for so many teachers. And it reminded me of a residency I had in a school where the staff barricaded themselves in the staff room at break and ignored all extraneous noises until it was time to venture out again. Only the head was brave enough to park his car in the school car park. As the writer in residence I often got treated as a free babysitter. I was abandoned on a Friday afternoon with year 11XX by a teacher who grinned wolfishly before declaring a dentist's appointment and scarpering. Several of the students disappeared shortly afterwards and some of the others began practising basket ball with the light fitting over the blackboard. Creative Writing? It was a free-for-all. But one of the students came up at the end and asked for my autograph. I must have looked puzzled because he added 'Just in case you get famous!' I could never have been a school teacher.

It was a Yorkshire poet Bob Horne who introduced me to Steve Ely's poetry at a writers' retreat. I bought the Calder Valley Poetry pamphlet last year and I'm still reading it. Werewolf is a dark collection that looks at the world and records its tragi-comic realities without softening the message that we are a violent, deceitful species. 'Every Child Matters' begins:

not really

we profess to believe it but our actions say otherwise

'Werewolf' - Lucas Cranach the Elder

'Werewolf' - Lucas Cranach the Elder'The Death Dealer of Kovno' deals with the 1941 Jewish massacre in Lithuania. The poetry is compelling, even when the subject matter appalls. Peter Riley describes the collection as 'this narrative catalogue of the capacity for human harm' which 'becomes a song/story book that grips, fascinates and in a grim kind of way, delights.' Which is exactly how it feels.

All our moral 'givens' are questioned. We think we are morally superior? That concentration camps couldn't exist in the UK? No. Even the worst could happen here. In 'Spurn'

Once the decision was made

it was simply a matter of logistics.

Trains from ghettos all over the country

dropped their freight at Doncaster sidings,

where tantalising tastes of Southern Fried Chicken

licked around the cars

like tongues of heavenly vipers.

In the mythologies of the poetry, the Tigers of Tigerland, happy to co-exist ('Tigerland was a broad land and there was room enough for all.') are at first welcoming when the White Men arrive. But soon there are no more Tiger people - only a colonial folk tale of savage beasts who 'came howling from the hills like savages, raping women and slaughtering children, until Providence snuffed them out.'

Male violence in particular is put under interrogation. In a year that has seen the revelations of Trump and Weinstein, massacres in the US and Europe, and the horrors of ethnic violence in Yemen and Myanmar the poetry is both a dark mirror held up to ourselves and an honest reflection of the world beyond the page. It emphasises the fragility of our own, illusory, safety. The poetry is astonishing, both technically and linguistically. I'm still reeling from its impact.

Steve Ely is the author of a novel Ratmen (Blackheath Books), a biography - Ted Hughes's South Yorkshire (Palgrave MacMillan), and two other collections of poetry - Englaland and Oswald's Book of Hours, both from Smokestack.

Werewolf is £7.00 from Calder Valley Poetry

Published on October 23, 2017 16:30

October 18, 2017

Margaret Atwood and the Frankfurt Peace Prize

'A book is a voice in your ear,' Margaret Atwood said in her acceptance speech at the Frankfurt Book Fair on Saturday. Our capacity to create narratives and our delight in listening to them is what will save us in 'this strange historical moment' we find ourselves living through. Unlike animals we tell stories to pass on important information so that each generation can learn without having to discover things from scratch. But, she also warns, the narratives can fail. Like most human tools, they can be used for both good and bad.

"Along will come a wolf in sheep’s clothing, or even a wolf in wolf’s clothing, and that wolf will say: Rabbits, you need a strong leader, and I am just the one for the job. I will cause the perfect future world to appear as if by magic, and ice cream will grow on trees. But first we will have to get rid of civil society – it is too soft, it is degenerate –– and we will have to abandon the accepted norms of behaviour that allow us to walk down the street without sticking knives into each other all the time. And then we will have to get rid of Those people. Only then will the perfect society appear!

..... The rabbits freeze, because they are confused and terrified, and by the time they figure out that the wolf does not in fact mean them well but has arranged everything only for the benefit of the wolves, it is too late.

Yes, we know, you will say. We’ve read the folktales. We’ve read the science fictions. We’ve been warned, often. But that, somehow, does not always stop this tale from being enacted in human societies, many times over."

Her dystopian, futuristic books are a warning of what may happen if we don't pay enough attention to the narratives available to us. The Emperor has a habit of walking out in invisible clothing. She makes the point that in ancient times, artists and writers worked in the service of the state, but that, in more recent times, we have been expected to speak 'truth to power', give a voice to those who have been silenced and tell the stories that have been suppressed. We have been imprisoned for it, we have been shot for it - something that is very relevant today. Across the Middle East, Asia, Russia and China, there are journalists in prison for what they have written. Even here in Europe freedom of speech is under attack. I'm still reeling from the news that Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, was assassinated while investigating widespread corruption in the highest echelons of government. Her last blog post ended with the words 'There are crooks everywhere you look. The situation is desperate.' She was killed by a bomb placed under her car.

Margaret Atwood references the dangers in her speech. We are at a very dangerous historical junction when all our moral norms are in question and fake news sometimes obliterates the facts.

"The United States is experiencing such a moment. After the 2016 election, young people in that country said to me, “This is the very worst thing that has ever happened;” to which I replied, both “No, actually it’s been worse,” and also, “No it isn’t; not yet.” Britain is also having a difficult time of things right now, with much weeping and gnashing of teeth. And – in a less drastic way, but still – in view of its recent election – so is Germany. You thought that crypt was locked, but someone had the key, and has opened the forbidden chamber, and what will come creeping or howling forth? Sorry to be so Gothic, but there is cause for alarm on many fronts."

She also holds out hope, that while there are writers who are prepared to risk everything to communicate the truth, however unpalatable it might be, and while there are still readers willing to listen, we might just be able to survive.

Margaret Atwood was awarded the Frankfurt Peace Prize for her 'Political intuition and clairvoyace'. Read the complete speech Here.

My thanks to Rita Meier for the complete transcript of the speech.

Published on October 18, 2017 03:49

October 10, 2017

Traditional Gaelic Air: Chi mi na Morbheanna

Life has been at full stretch recently - no time for anything but running from one event to another! And writing (even blogs) has been put on one side. But

this beautiful Gaelic Air

(the title means the Misty Mountains) always makes me feel calmer. It's sung here by the Rankin Family, a Canadian folk group who live in an area of Canada where many of those dispossessed by the Highland Clearances settled and Gaelic is still spoken there.

Published on October 10, 2017 14:09

September 28, 2017

National Poetry Day: Against Hate, by Pippa Little

Sole passenger on an early morning tram

I'm half asleep when the driver brakes,

dashes past me, dives into a copse of trees,

gone for so long I almost get out to walk.

Then he's back, his face alight.

I saw the wren! Explaining

how he feeds her when he can

and her restless, secretive waiting.

We talk of things we love until the station.

I tell him of the Budapest to Moscow train

brought to a halt in the middle of nowhere,

everyone leaning out expecting calamity

but not the engine driver, an old man

kneeling to gather armfuls of wild lilies,

wild orchids. He carried them back

as you would a newborn, top-heavy, gangly,

supporting the frail stems in his big, shovel hands.

These are small things, but I pass them on

because today is bloody, inexplicable

and this is my act, to write,

to feel the light against my back.

© Pippa Little

from Twist, published by Arc, 2017

This is my favourite poem from Pippa Little's new collection, Twist, recently published by Arc. Pippa generously let us use this poem in our anthology 'Write to be Counted' , raising money for PEN International - an organisation that defends freedom of speech and the rights of writers all over the world.

The theme of National Poetry Day this year is 'Freedom'. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights". Nelson Mandela glossed this by saying that "to be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others". The world is a perilous place at the moment - 'bloody, inexplicable' - as Pippa writes. We need words like this more than ever.

Twist, by Pippa Little, Arc Publications, 2017

Postscript: -

The National Poetry Society's Stanza 2017 Competition, on the theme 'Walls', was won by Konstandinos Mahoney, who appears in 'Write to be Counted', and among the runners up were several more contributors including Joan Michelson and John Gohorry.

I'm half asleep when the driver brakes,

dashes past me, dives into a copse of trees,

gone for so long I almost get out to walk.

Then he's back, his face alight.

I saw the wren! Explaining

how he feeds her when he can

and her restless, secretive waiting.

We talk of things we love until the station.

I tell him of the Budapest to Moscow train

brought to a halt in the middle of nowhere,

everyone leaning out expecting calamity

but not the engine driver, an old man

kneeling to gather armfuls of wild lilies,

wild orchids. He carried them back

as you would a newborn, top-heavy, gangly,

supporting the frail stems in his big, shovel hands.

These are small things, but I pass them on

because today is bloody, inexplicable

and this is my act, to write,

to feel the light against my back.

© Pippa Little

from Twist, published by Arc, 2017

This is my favourite poem from Pippa Little's new collection, Twist, recently published by Arc. Pippa generously let us use this poem in our anthology 'Write to be Counted' , raising money for PEN International - an organisation that defends freedom of speech and the rights of writers all over the world.

The theme of National Poetry Day this year is 'Freedom'. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that "All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights". Nelson Mandela glossed this by saying that "to be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others". The world is a perilous place at the moment - 'bloody, inexplicable' - as Pippa writes. We need words like this more than ever.

Twist, by Pippa Little, Arc Publications, 2017

Postscript: -

The National Poetry Society's Stanza 2017 Competition, on the theme 'Walls', was won by Konstandinos Mahoney, who appears in 'Write to be Counted', and among the runners up were several more contributors including Joan Michelson and John Gohorry.

Published on September 28, 2017 03:15

September 18, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Uses of the Body as a Source for Allegory and Metaphor - Roy Marshall

The excavated skull of the affair and the built up

head of steam; the face of loss, a clock, a cliff; the teeth

of cogs, combs, the wind; the lips of pitchers, craters

and augers; the jaws of mull-grips and dilemmas, not to mention

death; the tongues of brogues and ancient Doc Martens;

the crotches of arches; the long arm of the church

and of boredom; the armpit of the paramilitary wing; the brow

of the beaten, the hill, of morning; the breast made clean; the skin

of milk and of a balmy evening; the hard shoulder of regret,

the hair of the dog and its breadth; the knuckle of attraction

and the pierced nipple of fate; the long femur of the terminally hip;

the greased palm and the padlocked heart of British Steel; the spine

of the barn, of stepping stones, of the poem; the vertebrae

of e-mail and the gonads of vulnerability; the nose of the drink,

of the parson, to the grindstone; the cheeks in lamé trousers

like two peaches in a solder fountain; the ear to the ground,

the chest, the sky; the tender inner thigh of expectation;

the eye of the storm, the potato and the sunflower;

of the hurricane, the needle, the target, the tiger;

of love, of god, of the beholder.

© Roy Marshall

The Great Animator, Shoestring Press, 2017

I'm a big fan of Roy Marshall's blog where he shares his thoughts on poetry and often leads me to poets I might not have sought out myself. I've also been intrigued by comments from friends about his new collection, The Great Animator, published by Shoestring Press, so I ordered a copy. It didn't disappoint.

Another poet once told me that when you put a collection together you should aim to have three or four stand-out, 'wow' poems in it - that was all the reader could expect. The rest would generally be well-crafted, middle of the road stuff. Roy Marshall doesn't seem to have been given that advice. There are a lot of 'wow' poems in this collection. And the way the poems are arranged mean that they feed off each other, having conversations across the pages as well as with the reader.

From Horses, to Crow Etiquette, and the longevity of a tortoise, to the ghoulish science of the body farm and the teeth taken from bodies killed at Waterloo to make falsies for the toothless rich back home in England - there's surprise and and discovery on almost every page.

Roy Marshall worked as a cardiac nurse, so it's only to be expected that some of the best poems, like the one above, are grounded in the physical. Structures and Pathways, Sterile Field, Breaking the News, Shocks, are all poems that deal with the reality of working at the interface of life and death. My favourite poem from this section was 'Carrying the Arrest Bleep' that begins:

'It's cool, at first, to feel it

weighting my pocket, to be wired to a voice

swathed in static,

to run through empty corridors

past a gallery of night-blacked windows,

down stairwells

the smell of the dust

drifting in the hospital's

concrete heart. . . '

Then the brutal reality of CPR, the Frankenstein electric shocking of fragile, aged bodies with the intention of bringing them back to some semblance of life - the process is described in such a way as to question our attitude to death and our obsession with the preservation of life at all costs.

'all our futures laid bare

in a strip-lit bay, the whole scene

lasting far too long

and when the registrar asks

if we agree to stop, I meet

his eye, and nod.'

It resonates with the title poem, The Great Animator, which addresses our belief systems in some form of creation and control;

A God to Hindu and Lakota, you masquerade

as four stags of Norse myth, the deity

Fei Lan, sweeping haze-draped Beijing.

The poem is infused with the ambiguity in the title - puppeteer or creator? 'Destroyer of doldrums, transformer of slender sail/to pregnant belly . . . Yours is the hand/encircling the cool and fevered planet . . . Sand twister,/builder of pyramids,/you stop the eyes and mouths/of ruined places.' And then comes the revelation in the last two lines;

Meet me again on that ledge where

arms outstretched I leaned and was held.

The Great Animator, Roy Marshall, 2017 £9.50 inc postage and packing

Roy Marshall was born in 1966. His mother was born in Italy, his father in London. Roy wanted to be a writer as a child and young man but became distracted for about twenty years during which time he found himself variously employed as a delivery driver, gardener and coronary care nurse, amongst other occupations.

His previous publications are:

Gopagilla, Crystal Clear Press, 2012

The Sun Bathers, Shoestring Press, 2013 (shortlisted for the Michael Murphy award)

head of steam; the face of loss, a clock, a cliff; the teeth

of cogs, combs, the wind; the lips of pitchers, craters

and augers; the jaws of mull-grips and dilemmas, not to mention

death; the tongues of brogues and ancient Doc Martens;

the crotches of arches; the long arm of the church

and of boredom; the armpit of the paramilitary wing; the brow

of the beaten, the hill, of morning; the breast made clean; the skin

of milk and of a balmy evening; the hard shoulder of regret,

the hair of the dog and its breadth; the knuckle of attraction

and the pierced nipple of fate; the long femur of the terminally hip;

the greased palm and the padlocked heart of British Steel; the spine

of the barn, of stepping stones, of the poem; the vertebrae

of e-mail and the gonads of vulnerability; the nose of the drink,

of the parson, to the grindstone; the cheeks in lamé trousers

like two peaches in a solder fountain; the ear to the ground,

the chest, the sky; the tender inner thigh of expectation;

the eye of the storm, the potato and the sunflower;

of the hurricane, the needle, the target, the tiger;

of love, of god, of the beholder.

© Roy Marshall

The Great Animator, Shoestring Press, 2017

I'm a big fan of Roy Marshall's blog where he shares his thoughts on poetry and often leads me to poets I might not have sought out myself. I've also been intrigued by comments from friends about his new collection, The Great Animator, published by Shoestring Press, so I ordered a copy. It didn't disappoint.

Another poet once told me that when you put a collection together you should aim to have three or four stand-out, 'wow' poems in it - that was all the reader could expect. The rest would generally be well-crafted, middle of the road stuff. Roy Marshall doesn't seem to have been given that advice. There are a lot of 'wow' poems in this collection. And the way the poems are arranged mean that they feed off each other, having conversations across the pages as well as with the reader.

From Horses, to Crow Etiquette, and the longevity of a tortoise, to the ghoulish science of the body farm and the teeth taken from bodies killed at Waterloo to make falsies for the toothless rich back home in England - there's surprise and and discovery on almost every page.

Roy Marshall worked as a cardiac nurse, so it's only to be expected that some of the best poems, like the one above, are grounded in the physical. Structures and Pathways, Sterile Field, Breaking the News, Shocks, are all poems that deal with the reality of working at the interface of life and death. My favourite poem from this section was 'Carrying the Arrest Bleep' that begins:

'It's cool, at first, to feel it

weighting my pocket, to be wired to a voice

swathed in static,

to run through empty corridors

past a gallery of night-blacked windows,

down stairwells

the smell of the dust

drifting in the hospital's

concrete heart. . . '

Then the brutal reality of CPR, the Frankenstein electric shocking of fragile, aged bodies with the intention of bringing them back to some semblance of life - the process is described in such a way as to question our attitude to death and our obsession with the preservation of life at all costs.

'all our futures laid bare

in a strip-lit bay, the whole scene

lasting far too long

and when the registrar asks

if we agree to stop, I meet

his eye, and nod.'

It resonates with the title poem, The Great Animator, which addresses our belief systems in some form of creation and control;

A God to Hindu and Lakota, you masquerade

as four stags of Norse myth, the deity

Fei Lan, sweeping haze-draped Beijing.

The poem is infused with the ambiguity in the title - puppeteer or creator? 'Destroyer of doldrums, transformer of slender sail/to pregnant belly . . . Yours is the hand/encircling the cool and fevered planet . . . Sand twister,/builder of pyramids,/you stop the eyes and mouths/of ruined places.' And then comes the revelation in the last two lines;

Meet me again on that ledge where

arms outstretched I leaned and was held.

The Great Animator, Roy Marshall, 2017 £9.50 inc postage and packing

Roy Marshall was born in 1966. His mother was born in Italy, his father in London. Roy wanted to be a writer as a child and young man but became distracted for about twenty years during which time he found himself variously employed as a delivery driver, gardener and coronary care nurse, amongst other occupations.

His previous publications are:

Gopagilla, Crystal Clear Press, 2012

The Sun Bathers, Shoestring Press, 2013 (shortlisted for the Michael Murphy award)

Published on September 18, 2017 16:30

September 16, 2017

The Writer's Enemy No. 1

I have a new collection of poems coming out next week and I’m torn, as usual, between elation and fear. One part of me wants to pop the champagne cork (or rather, prosecco, since poets rarely earn enough for champagne!) – the other part wants to hide in a dark cupboard until it’s all over. Like most writers, I dread the moment the poor little creative thing I’ve cherished for so long, has to go out stark naked and face a critical audience. Just at this moment, I don’t want to put pen to paper ever again.

I have a new collection of poems coming out next week and I’m torn, as usual, between elation and fear. One part of me wants to pop the champagne cork (or rather, prosecco, since poets rarely earn enough for champagne!) – the other part wants to hide in a dark cupboard until it’s all over. Like most writers, I dread the moment the poor little creative thing I’ve cherished for so long, has to go out stark naked and face a critical audience. Just at this moment, I don’t want to put pen to paper ever again.It's been a rough ride with this book. The first publisher went bust and it's taken me almost two years to find another. There were a lot of rejections - not because of the quality of the work, they all stressed, but because they didn't have the resources. Many little poetry presses are committed a couple of years ahead. Some get no financial support from arts agencies. For other publishers it was down to the editor's personal preferences. It was very depressing. Some nice words from Bloodaxe's Neil Astley helped a lot, and two or three poet friends kept me going. Before I struck lucky with Indigo Dreams, I so very nearly gave up.

So what is a writer’s No.1 Enemy? Not Procrastination (though it may be a symptom). No. What kills your ability to write successfully is Self-Doubt. It's corrosive and eats away at your confidence from the inside out.

I’ve recently been contacted by a friend, the author of a number of books for both children and adults who also writes for TV, who is currently having a bit of a creative wobble. Her last book was ruthlessly carved up by her publishers and marketed as something that didn’t resemble what she’d written and she’s still unhappy with the result. Now she’s struggling with her latest project. She has taken extra care to hit what she thought was the button her publishers wanted her to press, but the book came back from her agent with ruthless requests for cuts, which she gritted her teeth and made. Then there was the email asking for ‘just a few tweaks’. Then the ‘we’re nearly there, but .....’ and ‘there are a few issues we’d still like you to address’. And so it goes on. My friend has begun to doubt whether the book is any good at all (it is) and she wonders whether she can still write, or has she lost the magic gift? I don’t think so.

Pic by Teela 'Battling self-doubt as a designer'.My friend is having an acute attack of Self-Doubt - a kind of inner torture that wakes you at 3am with a little voice at the back of your mind that tells you you’re no good; you’ll never get anywhere; give up now - it’s just not worth the pain and the effort; and did you really want to be a writer anyway? Surely there must be easier ways of not making a living? I know - I’ve been there. You fear being humiliated. You fear putting work in front of professional editors who will sneer at it behind your back, and - most of all - you fear being found out as a fake. Think you could be a writer did you?

Pic by Teela 'Battling self-doubt as a designer'.My friend is having an acute attack of Self-Doubt - a kind of inner torture that wakes you at 3am with a little voice at the back of your mind that tells you you’re no good; you’ll never get anywhere; give up now - it’s just not worth the pain and the effort; and did you really want to be a writer anyway? Surely there must be easier ways of not making a living? I know - I’ve been there. You fear being humiliated. You fear putting work in front of professional editors who will sneer at it behind your back, and - most of all - you fear being found out as a fake. Think you could be a writer did you?No matter how many books you’ve written successfully, the demon is always there, because - really - weren’t they all just massive strokes of luck? And it’s this one, the one you’re writing now, that is going to expose you for what you really are.

There’s only one way to deal with demons. Look them squarely in the eye and tell them to ‘Vaffanculo!’ - as Salvo Montalbano would say.

Love yourself a little. See what you’ve achieved? You’ve written a whole book. Share your work with kind friends as well as editorial critics. Believe in yourself.

We’re so easy to take down. A few comments from an agent or editor, a bad review, a couple of rejections and our creative souls are burning in the fires of publishing hell, with self-doubt turning up the heat.

Don’t immediately impale yourself on your pen. Your agent/editor/critics aren’t necessarily right. Drink wine, eat cake. Buy a new notebook. Some flowers. Believe the memes. Don’t let the B******s get you down!

Published on September 16, 2017 14:30

September 11, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Put-downs by Pauline Yarwood

My gran got it the wrong way round.

You're a sight for sore eyes, she'd snap,

sharp, when I snuck in through the back door.

I'd be grubby from digging pits for dens

or scratched and bleeding from climbing trees,

red-faced from riding my bike a few feet

further than I was allowed to go,

then a sweaty race back hoping not to be seen,

and once hiding in tall grass being shown how boys pee.

It was years before I realized that being

a sight for sore eyes was a good thing,

a joy to behold. But I was never that,

just a scruffy kid hoping for toast and marmite

and a bit of a welcome. She could, I suppose,

have meant that me looking like something

the cat dragged in cheered her up, made her smile.

But that wasn't my gran. A woman wrapped in loss,

her other favourite phrase, which never leaves me,

was who do you think you are.

She could destroy you six different ways with this

depending on where she put the emphasis.

Copyright Pauline Yarwood, 2017

from Image Junkie, Wayleave Press, 2017

This is Pauline Yarwood's debut pamphlet and it's very enjoyable. The poems are written in an easy, conversational voice that speaks straight to the reader. They are perceptive, sometime elegiac, often with a wry humour. The poem I've chosen manages to include it all. I like 'Put-downs' because it reminds me of my own Tyneside grandmother who used the expression regularly and with similar ambiguity. It's a poem full of character, laying bare the relationship between a child, not yet secure in their own identity, and a rather austere - 'spare the rod and spoil the child' - kind of figure. Even as I'm smiling at the humour of it, I'm feeling the same sadness and regret for what could have been, as the poet herself seems to feel. It's a poem about the loss of a relationship that might have been, foundering on that corrosive erosion of self-esteem and identity summed up by the mocking phrase 'Who do you think you are?'

This is Pauline Yarwood's debut pamphlet and it's very enjoyable. The poems are written in an easy, conversational voice that speaks straight to the reader. They are perceptive, sometime elegiac, often with a wry humour. The poem I've chosen manages to include it all. I like 'Put-downs' because it reminds me of my own Tyneside grandmother who used the expression regularly and with similar ambiguity. It's a poem full of character, laying bare the relationship between a child, not yet secure in their own identity, and a rather austere - 'spare the rod and spoil the child' - kind of figure. Even as I'm smiling at the humour of it, I'm feeling the same sadness and regret for what could have been, as the poet herself seems to feel. It's a poem about the loss of a relationship that might have been, foundering on that corrosive erosion of self-esteem and identity summed up by the mocking phrase 'Who do you think you are?'

The title poem, 'Image Junkie', describes an uneasy interaction with any peopled landscape.

'Time was, I'd wait for as long as it took

for someone to move out of the frame

so I could walk into the desolation . . .'

The narrator of the poem is detached, framing empty streets, vacated chairs and park benches, with a photographer's eye. But the people creep 'in slowly', asserting themselves. 'You may think you're on the margin', the poem continues:

'but you'd be surprised how many people

look directly at you,

challenging your right.'

Being alive is difficult and sometimes painful.

Pauline Yarwood is a poet and ceramicist living in the Lake District. She is a member of Brewery Poets in Kendal and, with Kim Moore, organises the Kendal Poetry Festival - rapidly becoming one of the best little festivals in the north. You can find out

more about her here.

Pauline Yarwood is a poet and ceramicist living in the Lake District. She is a member of Brewery Poets in Kendal and, with Kim Moore, organises the Kendal Poetry Festival - rapidly becoming one of the best little festivals in the north. You can find out

more about her here.

You can follow Pauline on Twitter @YarwoodPo

Wayleave Press was set up by award-winning poet Mike Barlow to fill a gap for poets he admired whose work wasn't finding a home with other presses in an increasingly crowded market. Each pamphlet is beautifully designed and edited, and he's publishing some interesting names. If you want to find out why Mike turned from poet to editor, there a good article about the press here .

Mike Barlow, editor, Wayleave Press

Mike Barlow, editor, Wayleave Press

You're a sight for sore eyes, she'd snap,

sharp, when I snuck in through the back door.

I'd be grubby from digging pits for dens

or scratched and bleeding from climbing trees,

red-faced from riding my bike a few feet

further than I was allowed to go,

then a sweaty race back hoping not to be seen,

and once hiding in tall grass being shown how boys pee.

It was years before I realized that being

a sight for sore eyes was a good thing,

a joy to behold. But I was never that,

just a scruffy kid hoping for toast and marmite

and a bit of a welcome. She could, I suppose,

have meant that me looking like something

the cat dragged in cheered her up, made her smile.

But that wasn't my gran. A woman wrapped in loss,

her other favourite phrase, which never leaves me,

was who do you think you are.

She could destroy you six different ways with this

depending on where she put the emphasis.

Copyright Pauline Yarwood, 2017

from Image Junkie, Wayleave Press, 2017

This is Pauline Yarwood's debut pamphlet and it's very enjoyable. The poems are written in an easy, conversational voice that speaks straight to the reader. They are perceptive, sometime elegiac, often with a wry humour. The poem I've chosen manages to include it all. I like 'Put-downs' because it reminds me of my own Tyneside grandmother who used the expression regularly and with similar ambiguity. It's a poem full of character, laying bare the relationship between a child, not yet secure in their own identity, and a rather austere - 'spare the rod and spoil the child' - kind of figure. Even as I'm smiling at the humour of it, I'm feeling the same sadness and regret for what could have been, as the poet herself seems to feel. It's a poem about the loss of a relationship that might have been, foundering on that corrosive erosion of self-esteem and identity summed up by the mocking phrase 'Who do you think you are?'

This is Pauline Yarwood's debut pamphlet and it's very enjoyable. The poems are written in an easy, conversational voice that speaks straight to the reader. They are perceptive, sometime elegiac, often with a wry humour. The poem I've chosen manages to include it all. I like 'Put-downs' because it reminds me of my own Tyneside grandmother who used the expression regularly and with similar ambiguity. It's a poem full of character, laying bare the relationship between a child, not yet secure in their own identity, and a rather austere - 'spare the rod and spoil the child' - kind of figure. Even as I'm smiling at the humour of it, I'm feeling the same sadness and regret for what could have been, as the poet herself seems to feel. It's a poem about the loss of a relationship that might have been, foundering on that corrosive erosion of self-esteem and identity summed up by the mocking phrase 'Who do you think you are?'The title poem, 'Image Junkie', describes an uneasy interaction with any peopled landscape.

'Time was, I'd wait for as long as it took

for someone to move out of the frame

so I could walk into the desolation . . .'

The narrator of the poem is detached, framing empty streets, vacated chairs and park benches, with a photographer's eye. But the people creep 'in slowly', asserting themselves. 'You may think you're on the margin', the poem continues:

'but you'd be surprised how many people

look directly at you,

challenging your right.'

Being alive is difficult and sometimes painful.

Pauline Yarwood is a poet and ceramicist living in the Lake District. She is a member of Brewery Poets in Kendal and, with Kim Moore, organises the Kendal Poetry Festival - rapidly becoming one of the best little festivals in the north. You can find out

more about her here.

Pauline Yarwood is a poet and ceramicist living in the Lake District. She is a member of Brewery Poets in Kendal and, with Kim Moore, organises the Kendal Poetry Festival - rapidly becoming one of the best little festivals in the north. You can find out

more about her here.

You can follow Pauline on Twitter @YarwoodPo

Wayleave Press was set up by award-winning poet Mike Barlow to fill a gap for poets he admired whose work wasn't finding a home with other presses in an increasingly crowded market. Each pamphlet is beautifully designed and edited, and he's publishing some interesting names. If you want to find out why Mike turned from poet to editor, there a good article about the press here .

Mike Barlow, editor, Wayleave Press

Mike Barlow, editor, Wayleave Press

Published on September 11, 2017 16:30

September 10, 2017

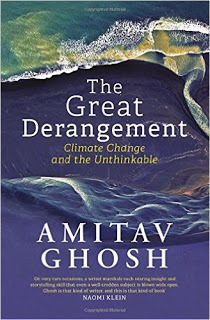

Sunday Book: The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh

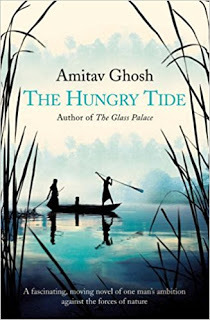

One of my favourite books of all time is ‘The Hungry Tide’ by Amitav Ghosh. It tells the story of a young scientist who goes into the Sundarbans of Bangladesh to find a rare and endangered dolphin. The Sundarbans are one of the lowest lying areas of Bangladesh - part of the Bengal Delta, vulnerable to rising sea levels and super-storms. At the climax of the novel the heroine finds herself trapped, with her lover, out in the mangrove swamps by a typhoon and experiences the destructive fury of a tropical hurricane.

Now, Amitav Ghosh has turned to non-fiction to bring climate change and ‘the unthinkable’ prospects for vulnerable populations, to the attention of the literary world.

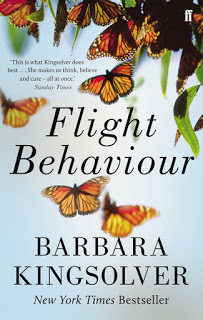

Why, he asks, are so few writers incorporating extreme climatic events into literary fiction? Why must it always be confined to the genres of dystopian, or speculative fiction? Or it is listed in the new genre springing up ‘Eco-fiction’. Among the few writers who do address it are Margaret Atwood, Barbara Kingsolver and, of course, Amitav Ghosh himself.

There are others, not mentioned by Ghosh - Joni Rodgers excellent novel The Hurricane Lover, written out of the experience of hurricane Katrina, is one of those that springs to mind, and you may be able to add a couple of names to the list.

But, generally, as in the population at large, the realities of our future and that of our children, as well as the extreme weather events of our present, are largely ignored.

Climate change is nothing new. Amitav Ghosh’s family were themselves ecological refugees when, in the 19th century, the Padma river suddenly changed its course, washing away the village they lived in the land that surrounded it. Anyone born in the Bengal Delta is used to a shifting landscape. What has changed is the degree of change and the human element of its causation. We are in the ‘Arc of Acceleration’. There is also the difference that populations are no longer free to move in response to it. They become refugees and nobody wants them.

The Sinking Island ProjectThe Anthropocene, Ghosh asserts, ‘presents a challenge, not only to the arts and humanities, but also to ... contemporary culture in general’. Fiction that addresses it, is not ‘of the kind that is taken seriously by serious literary journals’. The ‘literary novel’, Ghosh writes, has, as part of its history, ‘been disdainful of plot and narrative’. Emphasis has been laid on the subtleties of human interaction - ‘style and observation, of everyday details, traits of character, or nuances of emotion’. Big exterior events that strain credibility have no place in literary fiction as it is defined. And this is despite the fact that these events are becoming part of our everyday experience.

The Sinking Island ProjectThe Anthropocene, Ghosh asserts, ‘presents a challenge, not only to the arts and humanities, but also to ... contemporary culture in general’. Fiction that addresses it, is not ‘of the kind that is taken seriously by serious literary journals’. The ‘literary novel’, Ghosh writes, has, as part of its history, ‘been disdainful of plot and narrative’. Emphasis has been laid on the subtleties of human interaction - ‘style and observation, of everyday details, traits of character, or nuances of emotion’. Big exterior events that strain credibility have no place in literary fiction as it is defined. And this is despite the fact that these events are becoming part of our everyday experience.Amitav Ghosh uses the word ‘uncanny’ to describe our experience of climate change. Not the goose-bump inducing supernatural, but the feeling we have when something familiar and predictable suddenly presents with ‘new menace and uncertainty’. What concerns him most is our 'imaginative failure', as writers and artists, in the face of it.

A big section of the book discusses our disconnection with the natural world - a process that began a long time ago. Once, he writes, our ancestors were very wary of the natural world, particularly the ocean. They chose to live in locations at a safe distance from the sea. Now these ocean views, or riverside retreats, are high-status locations - a symptom of our disconnection and hubris. We build with a reckless disregard for nature, indifferent to, or believing we can control, its risks. ‘Property values,’ he says, ‘would almost certainly decline if residents were to be warned of possible risks - which is why builders and developers are sure to resist efforts to disseminate disaster related information.’

An image of dystopiaThen he moves on to the politics of climate change, where even to talk about it risks a major confrontation with its deniers. Is this why serious literature avoids it? Amitav Ghosh asks serious questions. What is the place of the non-human in the modern novel? Why has the literary imagination become ‘radically centred on the human’ to the exclusion of all else?

An image of dystopiaThen he moves on to the politics of climate change, where even to talk about it risks a major confrontation with its deniers. Is this why serious literature avoids it? Amitav Ghosh asks serious questions. What is the place of the non-human in the modern novel? Why has the literary imagination become ‘radically centred on the human’ to the exclusion of all else?In another chapter Ghosh looks at the politics of carbon and the part that corporate consumerism played in the fate of Mahatma Gandhi. ‘Gandhi understood . . . that the universalist premise of industrial civilisation was a hoax; that a consumerist mode of existence, if adopted by a sufficient number of people, would quickly become unsustainable and would lead, literally to the devouring of the planet.’ Consumerism enriched people. Gandhi’s enemies brought him down.

Ghosh proposes no solutions to the situation except to identify the fact that it must be a collective response. Although we are all ultimately responsible for climate change, since we have all contributed to it in some way, it is corporations and governments, global organisations, that have to make the changes that can rescue us. He castigates the mass media for its bias due to the fact that ‘large sections are now controlled by climate sceptics and by corporations that have vested interests in the carbon economy’.

He stresses the urgency of the problem: ‘every year that passes without a drastic reduction in global emissions makes catastrophe more certain’. But offers a fervent prayer for hope:

‘I would like to believe that out of this struggle will be born a generation that will be able to look upon the world with clearer eyes than those that preceded it ... that they will rediscover their kinship with other beings, and that this vision, at once new and ancient, will find expression in a transformed and renewed art and literature’.

This book has taken my mind for a walk and made me think quite deeply about the role of writers and publishers and diseminators of the written and spoken word in what Ghosh calls the ‘Great Derangement’. Highly recommended.

The Great Derangement by Amitav Ghosh

Published by Penguin Random House, India

Published on September 10, 2017 08:30

September 9, 2017

The Weather Coming

As I pludged my way across the water-logged fields in my wellies this morning, my thoughts were on the other side of the Atlantic, with the victims of Hurricane Irma. The weather, across the world is changing - even here in one of the most temperate zones. I know to my cost the power of water to alter lives.

It's the end of the first week of September, but those of us who live in the north are already being pitched into an early autumn, without really having a summer. The weir outside the Mill is running high and fast. The ground is saturated. Many migratory birds have already left and the trees are turning.

It's still warm (by northern standards!) but there's already a cool feeling to the evenings. Along the river, autumn is beautiful, the water reflecting the turning leaves and the cloud patterns of the sky.

But all is not well. The river levels have been high and it doesn't take much rain to turn it into a raging torrent. All along the banks there's evidence of slippage, as the river eats into the soil and undercuts the trees until they fall. Some farmers have been planting willows to slow the onslaught.

Some trees have simply been unable to cope with the higher water table. This one on the edge of the river, healthy before Storm Desmond in 2015, is just about clinging to life.

As a child in the Caldbeck Fells, I was surrounded by elderly farmers who had learned their craft before the days of weather forecasting. Each one had their own special signs they swore by. A cool, damp summer was one omen for a long and stormy winter; early bird migration, huge molehills as the moles dug down deep - these were the things they looked for. Some quoted the berry harvest, others argued that a lack of red berries was the sign of a harsh winter - a lean summer, followed by a keen winter. Who knows? But this year the molehills on the river bank are very large indeed.

Published on September 09, 2017 09:31

September 5, 2017

Tuesday Poem: Michael Donaghy - 'Safest'

Angelus Novus

As in this amateur footage of a lynch mob when someone hoists a

metal folding chair and commences to batter the swinging corpse

even as others hack at its limbs with machetes, just so Achilles, his

frenzy a runaway train, yokes up his team and drags Hector's carcass

around and around like . . . Stop. Rewind.

Hector dying on his knees in the dust whispering Prove you're a

man, then, swear by your soul, swear by your gods you won't feed

my corpse to your dogs.

Fuck you spits Achilles. Freeze frame. Mid-blink, Hector looks into

Achilles' eyes and takes all the time in the world to recall his last

embrace of Andromache and, it hardly now surprises him, to look

back at the future advancing behind him, to his own father

kissing the hands of this killer, the monster taking Priam's hand and

weeping with him, the sound of their sobbing filling the camp. Play

on. Hector's face slams to the dust.

Try to look at this: blind flash victims. Nagasaki. In their endless

1945 they face the camera as unaware of the photographer as they

are of you, viewer, Just so, rage-blind Achilles cannot now glimpse in

Hector's eyes, just before they empty, the terrible pity.

© The Estate of Michael Donaghy 2005

From 'Safest', published by Picador, London 2005

Hector was the eldest son of King Priam of Troy and one of the Trojan's greatest warriors, though he opposed war with the Greeks. Drawn into the war he did not want to fight, he killed Patroclus - Achilles beloved companion. Subsequently, in a duel with the grief-enraged Achilles, Hector is killed and his body dragged round the walls of Troy for all to witness. It is a story of revenge and cruelty and the pointlessness of war - where heroes are compared to members of a lynch mob and their battles a cycle of endless killing in which no one really wins. Michael Donaghy makes the parallel with World War II and the nuclear bombs dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki, and in the last line echoes Wilfred Owen's lines:-

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.

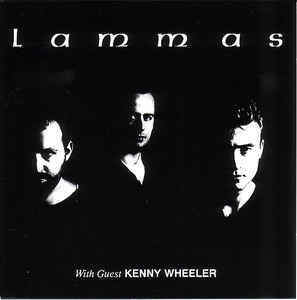

Michael Donaghy died suddenly, from a brain haemorrhage, in 2004 aged 50. He was Irish-American, brought up in New York, in the Bronx, where he witnessed endemic racism and every-day violence. Even as a young child he was drawn to books, spending time in the library rather than on the streets. He later said, “I owe everything I know about poetry to the public library system.” He went to university (which he referred to as his ‘miseducation’) and by the time he was in his early twenties he was the editor of the Chicago Review. Michael was also a musician and, when he moved to London in 1985, he joined Don Paterson and jazz musician Tim Garland to form the fusion music group ‘Lammas’.

Michael Donaghy's poetry was lyrical, always underpinned by form and rhythm, and often referencing the Irish folk music tradition. One of my favourite poems in this collection is ‘Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby . . .’ - which is only a fragment of an unfinished poem narrated by ‘Police Chief Francis O’Neill, Chicago, 1910'.

A review of his work in the Dark Horse (by David Mason), titled 'The Song is Drowned', said that: "He was a poet of bountiful erudition, energy and delight. Even his haunted moods, his premonitions of an early death, came on with the brightness and wit of an Ariel." Michael Donaghy's work is muscular, many-layered, profound, cross-cultural and multi-referenced.

‘Safest’ was the name of the file on his computer where he was storing poems intended for his next collection. It was published by Picador, edited by his partner Maddy Paxman, in 2005. Since then Michael Donaghy has dropped off the radar, as too often happens when poets die, leaving a big gap in the contemporary poetry spectrum. I was given this collection by a friend who works in a charity shop - ‘No one wants the poetry books,’ she said. Their loss is my gain.

Towards the end of the book is a poem that is almost prophetic, in the voice of a soul as it leaves the body and hovers over it in the emergency room. It is called Exile’s End.

You will do the very last thing.

Wait then for a noise in the chest,

between depth charge and gong,

like the seadoors slamming on the car deck.

Wait for the white noise and then cold astern.

Gaze down over the rim of the enormous lamp.

Observe the skilled frenzy of the physicians,

a nurse’s bald patch, blood. These will blur,

as sure as you’ve forgotten the voices

of your childhood friends, or your toys.

Or, you may note with mild surprise,

your name. For the face they now cover

is a stranger’s and it always has been.

Turn away. We commend you to the light,

where all reliable accounts conclude.

© The Estate of Michael Donaghy 2005

You can still buy Safest on Kindle and through second hand books on Amazon and from Abe Books.

As in this amateur footage of a lynch mob when someone hoists a

metal folding chair and commences to batter the swinging corpse

even as others hack at its limbs with machetes, just so Achilles, his

frenzy a runaway train, yokes up his team and drags Hector's carcass

around and around like . . . Stop. Rewind.

Hector dying on his knees in the dust whispering Prove you're a

man, then, swear by your soul, swear by your gods you won't feed

my corpse to your dogs.

Fuck you spits Achilles. Freeze frame. Mid-blink, Hector looks into

Achilles' eyes and takes all the time in the world to recall his last

embrace of Andromache and, it hardly now surprises him, to look

back at the future advancing behind him, to his own father

kissing the hands of this killer, the monster taking Priam's hand and

weeping with him, the sound of their sobbing filling the camp. Play

on. Hector's face slams to the dust.

Try to look at this: blind flash victims. Nagasaki. In their endless

1945 they face the camera as unaware of the photographer as they

are of you, viewer, Just so, rage-blind Achilles cannot now glimpse in

Hector's eyes, just before they empty, the terrible pity.

© The Estate of Michael Donaghy 2005

From 'Safest', published by Picador, London 2005

Hector was the eldest son of King Priam of Troy and one of the Trojan's greatest warriors, though he opposed war with the Greeks. Drawn into the war he did not want to fight, he killed Patroclus - Achilles beloved companion. Subsequently, in a duel with the grief-enraged Achilles, Hector is killed and his body dragged round the walls of Troy for all to witness. It is a story of revenge and cruelty and the pointlessness of war - where heroes are compared to members of a lynch mob and their battles a cycle of endless killing in which no one really wins. Michael Donaghy makes the parallel with World War II and the nuclear bombs dropped on the Japanese city of Nagasaki, and in the last line echoes Wilfred Owen's lines:-

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity.

Michael Donaghy died suddenly, from a brain haemorrhage, in 2004 aged 50. He was Irish-American, brought up in New York, in the Bronx, where he witnessed endemic racism and every-day violence. Even as a young child he was drawn to books, spending time in the library rather than on the streets. He later said, “I owe everything I know about poetry to the public library system.” He went to university (which he referred to as his ‘miseducation’) and by the time he was in his early twenties he was the editor of the Chicago Review. Michael was also a musician and, when he moved to London in 1985, he joined Don Paterson and jazz musician Tim Garland to form the fusion music group ‘Lammas’.

Michael Donaghy's poetry was lyrical, always underpinned by form and rhythm, and often referencing the Irish folk music tradition. One of my favourite poems in this collection is ‘Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby . . .’ - which is only a fragment of an unfinished poem narrated by ‘Police Chief Francis O’Neill, Chicago, 1910'.

A review of his work in the Dark Horse (by David Mason), titled 'The Song is Drowned', said that: "He was a poet of bountiful erudition, energy and delight. Even his haunted moods, his premonitions of an early death, came on with the brightness and wit of an Ariel." Michael Donaghy's work is muscular, many-layered, profound, cross-cultural and multi-referenced.

‘Safest’ was the name of the file on his computer where he was storing poems intended for his next collection. It was published by Picador, edited by his partner Maddy Paxman, in 2005. Since then Michael Donaghy has dropped off the radar, as too often happens when poets die, leaving a big gap in the contemporary poetry spectrum. I was given this collection by a friend who works in a charity shop - ‘No one wants the poetry books,’ she said. Their loss is my gain.

Towards the end of the book is a poem that is almost prophetic, in the voice of a soul as it leaves the body and hovers over it in the emergency room. It is called Exile’s End.

You will do the very last thing.

Wait then for a noise in the chest,

between depth charge and gong,

like the seadoors slamming on the car deck.

Wait for the white noise and then cold astern.

Gaze down over the rim of the enormous lamp.

Observe the skilled frenzy of the physicians,

a nurse’s bald patch, blood. These will blur,

as sure as you’ve forgotten the voices

of your childhood friends, or your toys.

Or, you may note with mild surprise,

your name. For the face they now cover

is a stranger’s and it always has been.

Turn away. We commend you to the light,

where all reliable accounts conclude.

© The Estate of Michael Donaghy 2005

You can still buy Safest on Kindle and through second hand books on Amazon and from Abe Books.

Published on September 05, 2017 03:45