Kathleen Jones's Blog

October 1, 2025

Jeopardy: 1066 Three Queens, One Crown - and a Poet

Jeopardy

JeopardyIt’s very difficult to write a novel when your readers are familiar with the plot and everyone knows how the story ends. Not much scope for surprise! That’s the challenge for anyone writing about 1066, and many writers and screen adaptors have crashed on those particular rocks.

There’s also the problem of historical authenticity; too much of it and the prose is dull and factual; too little of it and you’ll have knowledgeable readers calling you out on every social media platform. And you also have to avoid info-dumps. How do you supply readers who know little of history, the necessary facts they need in order to understand the story and characters, without the novel turning into a history lesson? All these things make historical fiction one of the most difficult genres to write.

The Bewcastle Cross

The Bewcastle CrossI’ve loved the Anglo-Saxons ever since I became interested in archaeology as a child. Being brought up in the north of England, not far from Hadrian’s wall, meant that there was a lot of it about. There are ancient standing stones and stone circles, Roman villas and forts, the great wall itself, and remnants of the Viking and Anglo-Saxon settlements. Cumbria and Northumbria have small, squat Anglo-Saxon churches, and a whole Viking town beneath modern York. We have Cuthbert and the Venerable Bede, the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Bewcastle Cross, the Ormside chalice and many, many more treasures from this period.

Ormside Chalice V&A

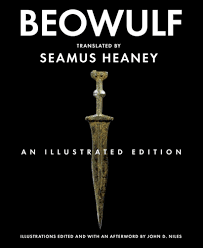

Ormside Chalice V&AAt university I read English and Medieval Studies, learning Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse, immersing myself in sagas and chronicles and poetry. They were written in a dialect I’d grown up with – northern tongues that still thrived in isolation when I was a child. ‘Aas gan yem,’ we’d say to each other after school – the same words a 9th century child would have spoken. Both the Northumbrian dialect and the Cumbrian dialect of the high fells were rooted in Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse.

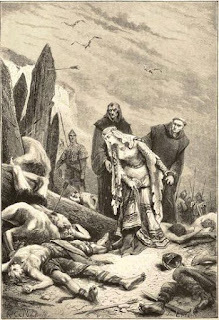

Harold's wife searching for his body

Harold's wife searching for his bodyWhy 1066? It’s always annoyed me that the story has been told from the Norman point of view (It’s always the victor who writes history!). What was the English version? And what were the women doing? There were enticing glimpses of them in the historical records – names entered as witnesses at council meetings, a marriage or a death. One of Harold Godwinson’s wives was recorded as searching for his body on the battlefield at Hastings when no one else could find it. Another wife vanished from history altogether. How did his first wife feel after he married a very beautiful woman young enough to be her daughter? How did his second wife feel about marrying the man who had murdered her first husband? I wanted to explore the answers to all these questions.

Queen Emma's Enconium

Queen Emma's EnconiumThen I discovered that the old dowager queen, Edward the Confessor’s mother Emma, had commissioned a biography of herself to put her ruthless, manipulative actions into a more sympathetic light. It was a self-hagiography that showed her sitting triumphantly on a throne with two of her sons, the size of small children, peeping around the corner. But it was striking that a woman would commission a book about herself. Then I found a book commissioned by her daughter-in-law, King Edward’s wife, Queen Edith Godwinsdottir, sister to Harold Godwinson. This purports to be a biography of her husband, Edward the Confessor, but more than half of it is the story of herself and her family. It’s intimate and revealing. In it she calls her eldest brother, Swein, a ‘gulping monster’. That’s definitely Edith talking – a Benedictine scribe wouldn’t dare to invent that!

Suddenly, it all came alive. There was another story to be told; one in which the women were the protagonists. Anglo-Saxon, or Anglo-Danish women, powerful, educated, land-rich, and independent, willing to tell their own stories.

The fourth character, Hari, a poet and bard, comes from the Norse and Danish sagas – a slave, bound to put their owner’s deeds into celebratory verse and make a precarious living at court. To make things even more risky, Hari is Hanne, a young Danish princess, who has avoided a much worse fate than slavery by dressing herself as a boy. She lives in permanent fear of discovery. There were many female poets and singers – the Norse sagas reveal quite a few, so there is ample historical evidence to back up Hanne/Hari’s character. She is the thread that connects them all, the witness to great events, whose ending no reader should be able to predict.

Jeopardy: 1066, Three Queens, One Throne – and a Poet is available on Amazon, or to order from all good bookshops. On this Link.

January 18, 2025

A Wartime Marriage

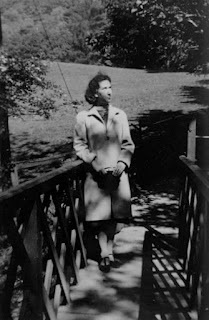

This is the story of a marriage. My mother, Ella, was 18 when she met David Brown in 1938. She was a shop assistant in the dress department of Fenwick’s department store in Newcastle; he was a travelling rep. for the firm. David was five years older than her, a serious young man, the only son of the widowed mother he supported. Neither Ella nor David had had the opportunity to get higher education, but both read widely and it was books that brought them together. It was how my mother made relationships. She was shy, with very little small talk and without much self-confidence, having been bullied by her own mother.

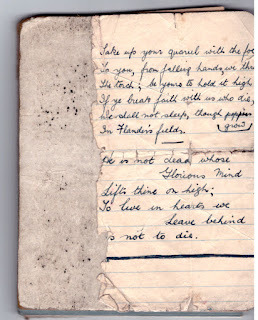

At first, she thought, it was just friendship. They went to a church youth group together, occasionally to the cinema and once a month to a classical concert. But David was deeply in love with the lovely Ella Sutherland, with her dark Italian hair and her quiet personality. He courted her with books and poetry. They both loved Wordsworth and a small collection of his poems were David’s first gift to her. My bookshelf still contains all the birthday and Christmas gifts he gave her – The Brothers Karamasov, poems by Rupert Brooke, a novel by Mary Webb, and a small volume of Milton’s collected poems. David himself wrote poetry and had ambitions as a poet.

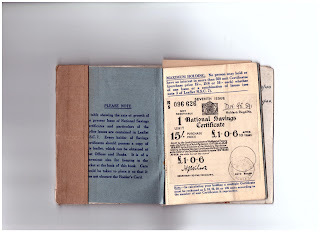

Soon my mother was very much in love for the first time. It was all or nothing with Ella. When she committed herself, she gave everything. Her family weren’t keen on an engagement. ‘A bit of a stuffed shirt’, my grandmother said when I asked her about David. My grandfather, a man of few words, summed him up as a ‘pompous bugger’. They didn’t think he’d make her happy. Their greatest adversary was David’s mother who didn’t want to lose her son to another woman and feared the loss of his financial support. Ella described Mrs Brown as ‘a very bitter woman’, who was too possessive towards her only son. ‘I’m sorry,’ Ella wrote in a letter, ‘but I just can’t love her,’ though she dutifully visited and drank tea out of porcelain cups in the parlour which was a shrine to her dead husband and her only son. There was also the question of where they would live. Ella couldn’t bear to live with her mother-in-law. They took out a savings account to put money aside for their future.

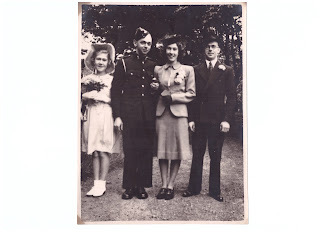

But the war intervened. David was called up and Ella’s family finally relented and allowed them to be married before he went off to a training camp down south. David’s mother didn’t come to the wedding. Ella’s father took the photographs. Her brother Gordon was the best man and her younger sister Joyce was the bridesmaid. The bridegroom was in uniform, the bride in a powder blue woollen suit from Fenwick’s. She looked radiantly happy. He looked nervous!

They honeymooned in the Lake District, a favourite place for both of them. My mother told me once that it wasn’t the passionate interlude they had hoped for. They were both virgins and she was so sore after the first time they made love it hadn’t been possible to repeat the experience. David, something of a prude, had shocked her by saying ‘I wish, now, that we hadn’t been so good.’ As soon as the precious weekend was over, David had to report for duty again and Ella went back to live with her parents. It was a marriage in limbo. Within a year David was told he was being sent abroad, to West Africa first, working on radar installations. They spent their embarkation leave in London, a city wrecked by the blitz. Newcastle too, was taking a pounding from German bombers and it wasn’t clear who was in the most danger, David or his wife.

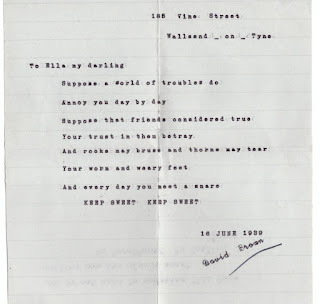

One of David's first letters, a poem 'Keep Sweet'

One of David's first letters, a poem 'Keep Sweet'Ella volunteered for the Land Army and was delighted to be sent to the Lake District. It was a safe place, away from the bombings that drove her parents into the air raid shelters almost every night and had reduced the streets around them to rubble. David sent letters and photograhs home from Africa, before being sent even further afield. He couldn’t tell her, but she thought it might have been the Far East. His letters were censored.

A postscript: 'My Sweetheart. My Darling. Always.'

A postscript: 'My Sweetheart. My Darling. Always.'In 1941, not long after he had been posted, she received a letter informing her that he was missing – that the ship he’d been on had been torpedoed. It was agony for her, but at least he wasn’t dead. The following year she received the letter she dreaded. ‘We regret to inform you . . .’ Even so, he was only presumed dead. Not knowing was terrible. By 1944 she was already in love with another man and in a torment of conflict. What if David came home at the end of the war? She made my father wait until the concentration camps were emptied in 1945. But David didn’t come home and she never had to make that choice.

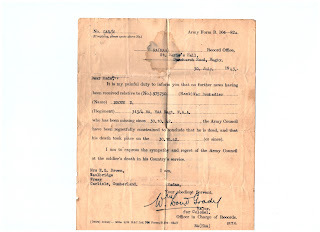

The tear-stained letter every war-time wife dreaded.

The tear-stained letter every war-time wife dreaded.After she died, I found the remnants of their relationship tucked into the corner of the wartime clutch bag she kept important documents in. Two tattered pages torn from a notebook with David’s poems written on them; a marriage certificate, a National Savings book; one love letter; a few photographs and a tear-stained War Ministry letter from David’s regiment giving her the devastating news that he was missing and now presumed dead. It was all that was left of their life together. Ella’s mother had thrown out the box containing all David’s letters and her other keepsakes when she re-married. David died for her all over again. ‘He wrote such beautiful letters,’ Mum told me. ‘And such lovely poetry.’ She never forgave her mother. Ella could recite Milton’s Lycidas by heart to us as children but cried every time she reached the lines; ‘He must not float upon his wat'ry bier/ Unwept’. When times were hard with my father (and they were) she was often tempted to think about what her life would have been like with David. I would find her crying in a dark corner, Milton’s poems, with their loving dedication, in her hands.

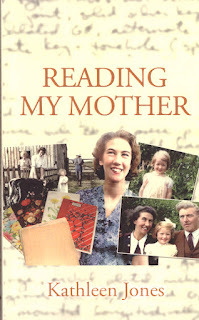

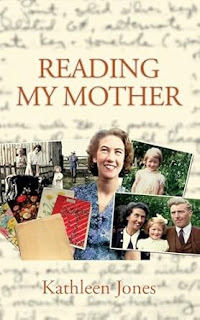

Reading My Mother: A Memoir

December 10, 2024

Conservation Choices

'Hope is not a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky. It is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency’. Rebecca Solnit, Hope.

Just a few steps away from diesel-belching lorries and the constant trans-Pennine tourist traffic of the A66, is an almost invisible track sloping steeply down to the edge of a turnip field. The footpath sign is obscured by elder and hawthorn, but I know where to look and how to find it.

Walking alone lets you notice things at micro-level – the way overnight rain has swirled the long grasses into patterns, the way the trees are colouring up – each species a different shade of yellow or amber. You notice the ghosts in the landscape too – deer toothmarks on the bark of a tree, the footprints of an otter on the sandy fringe of the river, the tracks of badger and fox.

I walk along the edge of the field, a row of ancient oak trees on my left in all their autumn colours. Some of them are so large it would take three people with arms outstretched to encircle their trunks. Among the oaks is a massive ash tree, only one or two branches still alive. Further on another has fallen in a recent gale, revealing the dark circles of die-back in the heartwood.

Below the trees, two or three metres down, you can glimpse the fast-running waters of the River Eamont flowing out of Ullswater, bringing cold mountain water down from Helvellyn, High Street and the other Cumbrian fells that surround the lake. The Eamont meanders, cutting semi-circles in the wide valley below the sandstone scarp I’m walking on.

It’s a mast year and the ground is thick with acorns, the hawthorn trees laden with red berries. Flocks of chaffinches and starlings are having an autumn feast in the branches, chattering among themselves, piping a warning call at the rustle of my approach. It’s good to see them thriving, but the lack of diversity of species this year, after the bird-flu epidemic, is worrying.

At the end of the turnip furrows I’m confronted by a slope of glaring yellow. It’s too late in the year for oil-seed rape, but it’s certainly luminous enough to be flowering rape. Curious, I go through the gate to investigate. Under my feet the grass has been cropped down to soil level, most of it now yellow, though there are odd tufts of green growing through. It’s quite a contrast to the lush green of the track I’ve been walking on.

Last time I came here this field was full of sheep and I realise that the yellow colour is evidence of a mineral deficiency in the soil, patchy circles where urine and droppings have leached the roots of the grass. Sheep-wrecked. There are large sacks of nitrate fertiliser stacked against the fence just inside the gate. The farmer is obviously intending to spread it for next year, an action that will create a run-off into the stream that runs down the boundary to the river below. He may even decide to reseed it; one of the further fields has already been ploughed up and resown with rye grass, the broad-bladed, identical shoots just creeping up out of the furrows. Monoculture. Intensive land use. This is modern farming, not the way my father cultivated the land, rotating crops and animals, using organic fertilisers. Old-fashioned perhaps, but it was kind to the land.

More evidence of change is in the broken-down stone wall that forms a boundary on two sides of the field – it’s gapped and tumbled along its entire length, gradually being replaced by the post and wire fence behind it. Walls shelter stoats, weasels, mice, lizards and other small creatures that owls and buzzards feed on. Modern farming methods create a desert for wild life. It’s not just red squirrels that are disappearing; at least nine other species are endangered here.

Beyond a plantation of pine and sycamore and birch, the track slopes down to the flood plain of the river. The traffic noise fades and I can only hear the river, explaining itself to the trees. And there, in its garth, is the tiny medieval church of Nine Kirks, standing on a more ancient site of habitation and worship. The river runs, deep and full, behind it, but the houses and little farms that used to be here have long gone, removed by Robert de Vieuxpont, Baron of Westmorland, a 13th century Norman aristocrat who wanted the fertile ground for his own purposes. He evicted people who’d lived here since the Romans left (and their ancestors probably longer), but kept the church. Land clearance has a long history.

I’m surrounded by sheep who’ve come up to see if I’ve brought anything to eat. They’re mainly twinters – a Cumbrian term for a ewe in its second winter. Their rumps are all either red or blue, showing that they’ve been recently ‘tupped’ and will be lambing in the spring. Empty-handed, I disappoint them and push through them to the church.

Inside the circular, walled enclosure there are old graves, tilting and toppling in the long grass. It’s an island of wild in this agricultural desert. There’s a ruined stone building where you could park your gig, and enough space to tie up your horse next to a mounting block.

The church, dedicated to St Ninian, existed in Norman times, and there’s evidence that there was an Anglo Saxon chapel here before that, when the settlement was already old. Hoards of Roman coins and Bronze Age artefacts have been dug up on the flood plain. The church was ‘modernised’ in the seventeenth century by a feisty female landowner called Lady Anne Clifford, and is now a Grade 1 listed building.

The heavy wooden door into the church is left unlocked for visitors and, inside, the silence is total. The thick walls are bare white stone, there are flagged floors, carved oak Tudor pews, an elaborate ‘priest’s door’and a well-preserved medieval chest for vestments. A single stained glass window has survived in glorious colour.

It stinks of damp and mildew. Above the simple altar the Lord’s Prayer and the Creed are painted for a congregation without books. I’m not religious, but some echo of the people who came here, were christened, married and mourned inside these walls, seems to linger. Local communities thought this building important enough to preserve long after its congregation had departed. I sit quietly absorbing the stillness thinking that it’s a pity we don’t have the same reverence for the natural world. We preserve human constructions much more readily than ecosystems.

On the way back I notice things I didn’t see on the way in. Some small animal, probably a fox, has dug an expert hole under the fence and left a track through the undergrowth. I lose it under some gorse bushes, but I’m glad to know that it’s there. In the field, a plastic tub, that once contained a mineral lick for the sheep, has turned itself into a miniature pond, with tall grasses and rotting vegetation. A dead baby frog hangs motionless in the anaerobic water just below the surface. We are a careless species.

The sun is going down behind the northern fells as I walk back through the turnip field. It’s late in the year and the dark falls quickly. I stand for a moment looking at the oak trees and the river. A flock of crows clatters overhead, heading for their roost. I’m thinking about land management over the millenia, from present day commercial farming, to the ancestors who lived off the land as hunter gatherers after the ice retreated. What will this landscape look like in the time of future generations? This section of the A66 is due to be widened into the turnip field. Inevitably, some of the oaks will go. Is transport really more important than the natural world? Is that question even being debated seriously by those who make the decisions?

Rachel Carson wrote in the nineteen fifties that ‘the central problem of our age has ... become the contamination of man’s total environment’ which she believed to be ‘irrecoverable and mostly irretrievable’, due to the length of time pesticides, herbicides and other pollutants linger in the environment. But reclamation science has come a long way since then.

And we must always have hope – that the impetus that preserved a medieval church in a field far from human habitation, can rescue and preserve the land that surrounds it. Rebecca Solnit writes that hope rooted in rage and grief can be powerful. But we have to use it. ‘Hope is not a lottery ticket you can sit on the sofa and clutch, feeling lucky,’ she stresses. ‘It is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency’.

We are living in a time of climate and environmental emergency. But inside the word ‘emergency’ is the word ‘emerge’. We have to have hope and we have to use it.

September 25, 2024

Sir Gawain the Fair and Medieval Misogyny

Sir Gawain, son of Lot, King of Orkney

Sir Gawain, son of Lot, King of OrkneyI’ve just been listening to a new translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight – one of the central tales that’s come down to us from the ‘histories’ of King Arthur’s court and the Knights of the Round Table. These are romantic legends that, in western culture, we’ve been brought up with. They surround us with a comforting account of the ethical codes of loyalty, courage, chivalry and purity that belong to a supposedly golden age of society, where men were men and could be relied on to defend a damsel in distress, rescuing her from demons and dragons and swearing eternal love and fidelity. Fair Sir Gawain is a perfect example of this kind of chivalry. A gentleman of honour. Good so far?

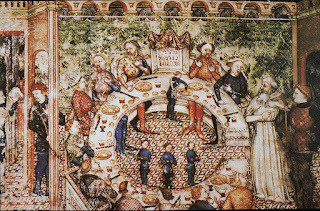

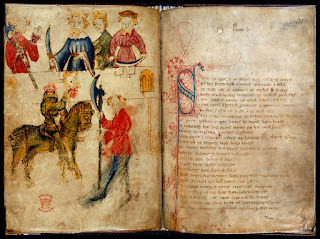

A medieval imagining of the Round Table

A medieval imagining of the Round TableBut I’d forgotten about the ending. In line with the rules that govern folk tales, Gawain must endure three trials in his quest for the mysterious Green Knight he’s promised to meet. Wandering in the wilderness in search of the rendezvous he is offered refuge from the winter weather at a luxurious castle. During his three day visit, Gawain promises his jovial host to offer up any gifts he receives while his host is out hunting, in return for lavish hospitality. But Gawain breaks his word on the final day and omits to disclose the protective golden belt his host’s beautiful wife has tempted him to accept. It will, apparently, save him from death. He’d had no trouble deflecting the young woman’s sexual advances, but fear for his own life had drawn him into deceit. So, when he faces the terrible Green Knight at the pagan Green Chapel, the demon is revealed as his host – the man whose hospitality he’s breached. Gawain is punished by a cut on the neck that creates a scar he will carry forever as a record of his failure to honour a promise to another man.

Gawain faces the Green Knight

Gawain faces the Green KnightGawain begins his lament with a prayer to god to protect him from women and their vile temptations. He had given in; like Adam yielding to Eve and damning the whole of humanity; King David tempted by Bathsheba’s naked form; Samson, betrayed by Delilah; Helen whose beauty caused the Trojan wars (an account of the Fall of Troy opens the poem in the original); and so the list grows – not of men who were betrayed into wrongdoing by their own desires and weaknesses, but the names of the women they blamed for ruining them and mankind for all eternity. According to the tale, women were entirely to blame for the catastrophes that have engulfed humanity. And we still are.

Stories matter. We are all brought up on the legends of the Holy Grail, fairy stories, Greek mythology, the tales handed down from generation to generation. In our culture, these stories are changed and tainted by the way they’ve been transmitted – oral tales written down by Christian monks and male scholars (because in almost every case they are) who’ve sought to impart a moral slant into a pagan inheritance. It’s religious and literary colonialism. If you can’t stop people telling the old stories, make sure you give them a twist that suits your own culture and beliefs.

The Wright Manuscript

The Wright ManuscriptChristianity has not been kind to women. Neither have the other Abrahamic religions (Judaism and Islam) that come from the same ancestor – the prophet Abraham who supposedly lived several thousand years ago. Remember him from Genesis? He was going to sacrifice his son – his elderly wife’s only child after decades of marriage – because he heard voices in his head telling him to do it. Fortunately he heard another voice telling him not to do it just as he was about to light the pyre. And then there’s his treatment of his other two wives, the slave Hagar (driven out into the wilderness) and the concubine Keturah. Only the names of the sons they ‘gave’ him are recorded.

A lot of work has been done by feminist (both male and female) historians to explore the origins of these patriarchal narratives. The stories may date back to approximately 2000 BC or the more recent Iron Age. They are of their time – a time when women’s lives were not valued except as fruitful wombs or the property they brought with them into marriage. But the message these stories carry has lingered for four millennia. We carry them in the marrow of our bones, they’re around us everywhere in books, films, television adaptations – we breathe the misogyny of mythology in our daily lives.

No wonder we’ve struggled to change it. We need new stories, a kinder narrative of our relationships to each other and to the natural world.

The fictional Gawain translated by Jesse Weston

September 13, 2024

Why Write a Memoir?

Who on earth wants to know about your life? Unless you’re a celebrity, or you’ve done something weird or ground-breaking. Maybe I’m just an attention-seeking, narcissistic idiot! I’ve had to think a lot about the ‘why’ – and it has a lot to do with my much-loved younger brother, Jon.

He died as a homeless alcoholic before he reached old age. He lay in hospital suffering from organ failure for almost two weeks before he died, alone, and his family weren’t told that he was there. It’s a wound that keeps on being re-opened.

Sitting in Birmingham railway station, on my way to the Historical Novel conference in Dartington, I was approached by a homeless man, aged about 50, very polite and non-threatening, who asked for money for a coffee. I asked him about himself and he told me that he was a drug addict on a programme, living in a homeless hostel and struggling to stay clean. He’d once had a good job, a wife, a house with a mortgage, until drugs had got hold of him. He was a lovely man – a former DJ (my brother was a rock guitarist and sound guy), fully aware of his situation and the probable consequences. He has a son he’s trying to keep in touch with.

And it made me think of my brother and the reasons why he came to such a terrible end. Jon had a fantastic wife, serial girlfriends, (all interesting, feisty women) and four lovely daughters – strong characters with creative, independent personalities. Jon had everything to live for.

Jon, standing. Barn Theatre rehearsal - his first band!

Jon, standing. Barn Theatre rehearsal - his first band!I started writing the memoir when Jon died, and I realise now that it was, in part, an attempt to unravel the past and find out what had gone wrong in my brother’s life that had made it so painful he had to drown it at the bottom of a bottle. We were much-loved as children. We had a happy childhood, didn’t we? But I came to realise that siblings experience things differently; what is happy for one isn’t necessarily happy for the other.

My father’s family was Irish and I discovered that there was a thread of alcoholism running through our genetic line: one great-grandmother, one of my aunts, a cousin and my brother. How much do genes contribute to a tendency to addiction?

There was always something different in my brother – an aloofness, a hidden anger. He cracked open one of our younger cousin’s skulls with a slate when he was 11 or 12 for no reason at all. When he was 17 he left home and disappeared, changing his name to avoid being traced. We didn’t know whether he was alive or dead for 10 years.

Jon in full song

Jon in full songEven after he’d got back in touch, contact with his family was sporadic and usually through his wife and girlfriends. After my mother’s funeral, we never spoke; fury on my part at the way he had treated my parents as their health failed; guilt on his about his own behaviour, plus resentment that I was more successful than he was (his perception, not mine).

I started looking for him again about a year before he died and found a post on Facebook, dating from a couple of years earlier, saying that I was a ‘terrible woman’, fake and insincere, and he wouldn’t want me at his funeral. That caused a great deal of soul-searching and made me even more determined to be there when it happened. But that was all I could find of him and it was so hostile I stopped looking. Other family members were in a similar position. The fact that he died in hospital without any of us knowing, was very bitter. No chance for us to have that last conversation, to say the things we would have liked to say. Forgiveness, reconciliation, love. No chance to ask questions either. Mainly ‘Why?’

Jon had an abundance of talent – he could sing before he could talk and had every opportunity to ‘make it’ as a musician. Instead he drank a bottle of Rioja for breakfast and we read about his life in the tabloid press. (My mother kept the cuttings).

Unhappy Jon, L front next to me. Scattering our father's ashes at Rough Close.

Unhappy Jon, L front next to me. Scattering our father's ashes at Rough Close.I’ve written about our childhood in Reading My Mother, the rest of it I’m still working my way through, figuring it out. Wendy Pratt, in the Ghost Lake, writes that being working class isn’t a great start – there’s a lack of aspiration built into our education and the community itself has a lack of role models to inspire us. In our family there was no lack of ambition, but perhaps without the confidence to believe we could get where we wanted to go. It was a constant struggle with Imposter Syndrome – ‘someone like me shouldn’t be doing this’. But many rock musicians came from working-class backgrounds, so for Jon it probably wasn’t that.

Perhaps I’ll find the answer before I get to the end of ‘Writing My Way Home’, the second part of the story. The man I met on Birmingham station says there is no answer – it’s a matter of luck in a random universe. Perhaps he’s right.

Order from Waterstones: https://tinyurl.com/345ac9ky

Barnes and Noble https://tinyurl.com/3r8sst4c

Bookends Cumbria: https://tinyurl.com/4nfk3hz9

Amazon: https://tinyurl.com/5ekn75ac

September 4, 2024

Losing your place

This piece was supposed to be about why I wrote a memoir. But I couldn’t stop thinking about Belonging and particularly about its opposite – Not Belonging. My mother, brought up in an industrial, shipyard town on Tyneside, longed for the Cumbrian Lake District which she’d visited for a holiday. As a teenager she copied some very tacky (for me) lines from Vita Sackville West about belonging to a particular place. In brackets underneath she wrote (That place, for me, is Ullswater.) Her life would take her to it but, thanks to my father’s Irish wanderlust, she spent very little of her life there.

Mum holding an invisible me

Mum holding an invisible meTalking about ‘place’ and ‘belonging’ when you no longer belong to that place can become nauseatingly sentimental; all those mournful Irish melodies that haunted my childhood, or the postcard of Helvellyn tipped with snow that my mother had tucked into a corner of the mirror frame in the living room. She used to look at it and sigh. But the linkage between place and person is more fundamental, more necessary than mere sentiment, and breaking that link can be brutal. Simone Weil wrote that ‘to be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognised need of the human soul’. Perhaps as important as being loved?

The loss of a homeland is a mixture of grief, longing and nostalgia and also a sense of displacement – you no longer know exactly who you are. The Portuguese have a word for it – saudade – which is untranslatable in English. The Welsh call it hiraeth. For the English the nearest is homesickness which doesn’t get close to the loss of identity that comes with the loss of ‘home’.

The displaced Palestinian writer and philosopher Edward Said, living in America, wrote an essay called ‘Reflections on Exile’ [Granta] in which he says that exile is ‘an unbearable rift between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home . . . to be torn from the nourishment of tradition, family and geography’ is severe deprivation.

It was certainly the case for me. I went to London as a teenager when my father went bankrupt and the Lake District farm had to be sold. My parents moved to Lincolnshire where Dad became a farm worker on an estate, living in a tiny house only big enough for my parents and my young brother. There was no room for me. The feeling of abandonment was enormous. I no longer had a home to go to.

Displaced: Kathie in 1967

Displaced: Kathie in 1967But, writing the memoir has made me realise that dislocation was part of what made me a writer. I’d always written poems and stories as a child, but being in exile from home and family somehow made the ambition sharper. Edward Said believed that exiles are drawn to creation, and to literature in particular. ‘A writer is almost always an outsider, nomadic, somehow in temperament – and that no matter where he or she lives or for how long, it is only in writing, in each attempt at a story, at a poem or a piece of text, that he or she can make something fixed in the midst of uncertainty, create a place of safety, be at home.’ [Granta, ‘Out of Place’]

The New Zealand novelist and memoirist, Janet Frame, went even further. ‘All writers are exiles wherever they live and their work is a lifelong journey towards the lost land.’ [Envoy from Mirror City] We are always writing our way back.

So, I went back through notebooks and letters and diaries and scrapbooks. I sorted old photographs in albums my mother had kept, laughed at some, tried to puzzle out the identities of anonymous faces in others, regretting the fact that she wasn’t there to ask. Why hadn’t I asked more questions when she was alive?

And I revisited places where I’d lived as a child. The farm cottage I was born in is now lost in a complex of converted holiday homes. The croft in the Cheviots above Bewcastle is still there, swallowed by an ocean of trees, home to a forest ranger as the Kershope forest has become a commercial sprawl. The old Bewcastle school has been demolished and replaced by a purpose-built modern structure. Low Ling at Rosley is now the lovely Georgian home it was always designed to be. The places have changed, as I’ve changed, over the time I’ve been away.

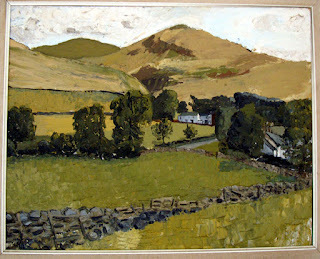

Rough Close by Gill Curwen

Rough Close by Gill CurwenBut Rough Close is much the same. The house was bought by the Curwen family who have used it as a holiday home and preserved it as it was with the addition of wood burning stoves and the conversion of the old dairy into a bathroom. It’s a much more comfortable place to live now. Gill Curwen, who died tragically young, was a painter and one of her paintings of Rough Close was given to me and hangs on my wall. She also wrote me letters, understood my connection to the place and allowed me to stay there with my children. * I will always be grateful to her. Rough Close will always be home, a special place, not just to me, but to a generation of cousins who stayed there when we were a rowdy bunch of children running wild on the fells and letting our imaginations romp through the barns and byres. This memoir is not just for me.

Pre-order Reading My Mother from Waterstones

https://www.waterstones.com/book/reading-my-mother/kathleen-jones//9781068699108

Barnes and Noble

Bookends Cumbria

https://www.bookscumbria.com/product/uk-books/biography-uk/reading-my-mother/

Amazon

August 23, 2024

Belonging

What is it about a particular place that makes us feel we ‘belong’? Sometimes it’s the place where we were born and spent the first part of our life – what psychologists call the ‘Primal Imprint’. But quite often it’s a place we have no connection to at all; a place we visit and where we suddenly feel at home. Belonging to a place is rather like recognising a partner for life, that sense of recognising ‘ourselves in each other’ that Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy felt when they met again after a long separation. There’s something about the place we belong that reflects something of ourselves back to us, almost like a memory.

I’ve just begun reading Wendy Pratt’s memoir ‘The Ghost Lake’ and have been moved by that account of her childhood and her attachment to a place that’s been inhabited since human beings first migrated north after the ice. She’s telling the history of the landscape she loves as well as her own. And it’s a north country, working class voice, like my own, talking about belonging and not-belonging.

For me, it’s a small white farmhouse sitting exposed on the edge of the most westerly Lakeland fells. It’s surrounded by a garth that protects it from the wind pouring off the Atlantic. There’s something about the sturdiness of the place – stonework an arm’s length thick, rooted to the bedrock – the permanence of a place that had a neolithic stone axe head in the barn floor; a place where people had lived for thousands of years. But it’s also the wildness of the place, existing in the teeth of the weather and somehow managing to endure whatever’s thrown at it.

That sense of belonging isn’t the recognition of any trait in myself, but of how I would like to be. Sturdy, enduring. The irony is that, ever since I was a child running around the stackyard, I longed to leave. I wanted to find out where the wind came from. When I looked up at the northern stars rolling overhead I wanted to know what the other half of the sky looked like. I got my wish. I left, though the leaving was traumatic, and spent the next twenty years as a nomad. There are only two other places in the world where I’ve felt that sense of belonging – Canada’s wild north west and New Zealand’s south island. Both wild and uncompromising with the same sense of exposure and risk. I belong in wild places, among mountains and rivers scoured out by extremes of weather.

Knowing where you belong is also knowing yourself and recognising your most uncomfortable feelings. My mother longed for security; I long for the exhilaration of its opposite. That incompatibility defined our relationship. But, belonging is also knowing where to return to. When I lived in the south of England and drove up the M6 to revisit the Lake District, even after it had ceased to be home, even when there was no family left to visit, there was a powerful, visceral feeling that stopped the breath in my mouth, when the first of the fells came into view over the horizon. It was a landscape I could step into, like walking into the frame of a painting, and know that I was utterly in the right place. The farm at Rough Close, high in the Uldale fells, was the one place where the childhood me and the adult me could be together, one and the same person. It was like putting the last piece into a 3000 piece jigsaw puzzle someone had given you for Christmas.

Reading My Mother, an account of that journey, is published on the 15th September.

September 28, 2023

Windswept by Anne Worsley: Review

When I started out as a writer I was told by a very experienced editor, ‘keep description to a minimum, keep the action moving or you’ll bore your reader’. For me, Windswept just has too much description - poetic, painterly though it is, the need to be original is sometimes strained too far.

Description is wonderful in itself, but not for 300 pages. I wanted a personal narrative to tie together the accounts of sunrises, sunsets, storms, seascapes and mountain views. I wanted more probing into the deep ecology of the landscape, the need to change how we live in it for the future. There is very little about the author’s personal journey and her struggle with crofting. Was there any?

The Highland Clearances are skimmed over. And at the end of the book there’s no real conclusion – a good book, particularly in ecoliterature, should change your outlook just a little, offer hope or stir you into action. My favourite piece was the return of the corncrakes. On the whole I enjoyed the book, though I felt that an editor with a red pen and a firm hand would have improved it considerably.

Don’t let that put you off! Immerse yourself in ‘Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands’. It is, after all, endorsed by Robert Macfarlane!

August 30, 2023

What Happened to Sally?

I first met the woman I'll call Sally when I was twenty, newly out of England, my first time on a plane. I was sitting in the lounge at Beirut airport, waiting out a twelve-hour transit, and I had a baby on my lap. Beirut airport was a confusing experience. I was fascinated by crowds of men talking staccato Arabic, some of the men wearing a European waistcoat over their long white robes, with a red Fez on their heads. There were women in black veils, the occasional Europeans - confident women in designer dresses with furs carried casually over their arms; the men in three-piece suits, followed by Arab boys with trolleys of luggage.

I became aware of a very tall woman with long blonde hair in a man's dishdashieh, a wide gold collar around her neck. She was striding up and down the rows of seats brandishing what looked like a very expensive camera taking photographs of the crowds. Sometimes she crouched down to get a better shot. She stopped in front of me and asked if she could photograph my small son, who was just beginning to toddle. Her accent was American - the full-on southern drawl, and her manner was bold almost to the point of rudeness. Feeling lost and vulnerable in a foreign country, I envied her assurance.

'What are you doing here?' she asked. I explained that I was flying out to the Gulf States to join a husband I hadn't seen for six months and had a long stopover. 'Then I must show you Beirut,' she said, impulsively. 'If you've never been here before you must see the most amazing city in the world.' I was commandeered, all protests silenced, and taken out of the airport, plane ticket and passport waved through by an airport official who seemed quite familiar with this force of nature who told me her name was Sally.

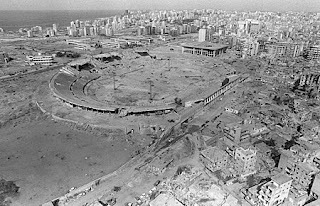

Beirut in the 1970s before the war

Beirut in the 1970s before the war Beirut - after the war

Beirut - after the warShe was in Beirut to take a series of photos for the National Geographic, she explained as she hailed an elderly Toyota taxi driven by an equally elderly man whose head was swathed in white, smoking a long cigarette out of the window. It was dark, but the city was ablaze with lights. She kept giving the driver instructions in a mixture of French and Arabic. At the Phoenicia Hotel he was ordered to wait while we went into the bar, where she bought me a glass of bourbon and exchanged banter with the barman who gave my son some sweets. Sally began to tell me details about her life. She'd been living in Venice, in a ground-floor apartment paid for by her Italian lover. But she'd had to leave after an exceptionally high Aqua Alta. She was a professional photographer and journalist - Vogue, Time Magazine, Geographic - and was now writing her first novel. She was a writer - everything I was trying to be. Sally seemed fascinated by my son, now asleep in my arms, and told me that she had a nine-year-old daughter who lived with her grandmother in Milwaukee.

Then it was back to the taxi and around the city, the corniche, where the bay stretched out into the Mediterranean, illuminated by the moon. We drove along the boulevards with their nightclubs and elegant Napoleonic facades, paused to look at the main square with its fountains and palm trees. Beirut, before it was shelled into rubble was one of the most beautiful cities. the meeting place, Sally told me, of European and Middle Eastern culture. 'But you just have to see the Roman temples at Baalbek by moonlight,' Sally said, made more enthusiastic by the bourbons she'd downed at the Phoenicia.

Roman Temples at Baalbek

Roman Temples at BaalbekShe gave instructions to the taxi driver who stopped suddenly in the middle of the street and demanded American dollars in advance for such a trip. Sally didn't have any and she seemed surprised to find that I didn't have any, not so much as a dinar of foreign currency on me, since I hadn't been expecting to need any. So we didn't go. But Sally pointed out to me the ring of mountains that edged the horizon, the moon just catching odd patches of white snow on their peaks.

The Phoenicia Hotel

The Phoenicia Hotel'You must come back and see it all!' she said. The sky was lightening in the east when she dropped me back at the airport. I put two pound notes I found in my pocket into the driver's hand as we went back inside and hoped it would be enough of a contribution.

I thought I would never see the woman who had erupted into my life like a volcano, again. I flew to Dubai on the morning flight and then took a DC3 to Abu Dhabi where the plane landed on the beach. A man was waiting for me, a stranger I didn't recognise, bearded, tanned to a shade of mahogany. Our son shrank from his father and wouldn't go near him for days. We were staying in a small room in a half-built hotel near the seafront. There was only space to walk round the bed we had to share with our son. Electricity depended on an old generator; there was no air conditioning and water only for an hour or so twice a day, or when the tanker arrived from the Buraimi oasis.

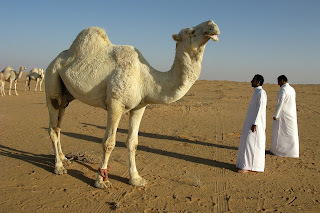

Camels in the Desert

Camels in the DesertWe were invited to a small reception at the Embassy. I was one of only six European women in the Sheikhdom so most of the guests were men, very smart in their white tropical evening jackets. But there, half a head taller than anyone in the room, was Sally, glass in hand, this time wearing a very short blue silk shift she told everyone was Christian Dior and had been a gift from a lover in Paris. She pounced on me, found out where I was staying and became a frequent visitor. Sally said she was still working for the Geographic, living in a room behind the Suekh for the 'genuine experience'.

When we moved out of the hotel into a prefabricated house shipped from Denmark, complete with contents, she became an even more frequent visitor. My house had air conditioning, so where better to sit out the afternoon heat than my sitting room. She would stay for hours, talking mainly about herself and the novel she was writing. Her agent in the US was very excited by the idea, she said. It was going to be about this young woman who finds herself adrift in the Arab world. I began to wonder if I was being used for copy.

By now I was pregnant again and finding the climate exhausting. I longed to spend the afternoon siesta in my air-conditioned bedroom. I began to avoid Sally. I locked my front door and went to bed, pretending not to hear the car, the knocking on the fly screen. 'Why are you hiding from me?' she asked one day when we met in the Suekh. I lied and said I wasn't, but she knew.

One day, when my son was at nursery, full of remorse, I drove into the group of houses behind the Suekh to try to find out where she was staying. I asked a small boy, in my rapidly improving Arabic, where the American woman lived. He pointed to a small white building and made a rude gesture. A big Cadillac was parked outside with the gold, crossed swords of the royal family on the number plate. I went away and came back a few days later.

She asked me in, grudgingly, making apologies for her way of living. 'It's all very simple,' she said, waving her arm round the single, white-washed room. 'There's no distractions.' She offered me lukewarm Coca-Cola and sat down on a rug on the floor, gesturing me to sit down opposite her. Her typewriter sat on a tin trunk that seemed to be the only piece of furniture she had. The floor was loose sand, a camping stove stood in a corner, pots and pans and carrier bags of food were hung on hooks on the walls - to keep them away from the rats, she said in a jokey way. 'And the cockroaches.'

'What do you do for the bathroom?' I asked. She showed me a corner of the yard outside, which had a bamboo screen around it. Inside, a hole in the ground buzzed with flies. There was a barrel of water and a plastic scoop that served as a shower. I was shocked. I was also worried about her. Sometimes when I saw her she was drowsy and spaced out, and I had begun to suspect that she was taking drugs. Hashish was everywhere in the Suekh, and so was opium. I wondered if this was one of the reasons that we never met Sally at parties anymore - the European community had closed ranks against her. She was unpredictable, charming when she was in the mood but riotous when she'd had a few drinks and liable to cause scenes. My husband wanted me to cut the connection. 'Everyone else has,' he said. 'She's bad news.' But I couldn't. I was beginning to write my own novel, and she was a character in it.

When my daughter was born in the local hospital, Sally gave me a framed photograph and signed it 'To a fellow traveller and a faithful friend.'

Then one day she came round to the house very agitated. The Sheikh had refused to sponsor her for another residence visa. She had to leave the country in two days' time. Would I keep her belongings for her until she had somewhere to stay and could send for them? Of course, I said. The next day she brought the tin trunk which contained, I was told, the Dior dress, the typewriter and the draft of her novel. 'I've sent the original to my agent,' she said. She had sold the gold necklace to pay for a flight to India.

I never saw her again. When we left Abu Dhabi I gave her trunk to the American Consul to keep for her. Later, back in England, a letter arrived, forwarded from Abu Dhabi by my husband's firm. It was already three weeks old. Would I wire her some money? Sally wrote. Urgently? She was destitute. Her cameras had been stolen and she was begging outside the airport in Delhi. Her mother had cut her off. I was her last hope. 'I need food,' she wrote, 'and a plane ticket out of here.'

I had no money of my own. I showed the letter to my husband, who refused to send her anything. 'The US Embassy will help her,' he said. 'It's her own fault she's in such a state.'

And that was the last contact I had with Sally - though I always hoped to find some trace of her in magazines, publishing news, the Geographic; but she had vanished. I'm still haunted by her.

May 6, 2022

Wild Places: Kathleen Mansfield and Flowers

When I open my eyes Mansfield is sitting on the end of my bed looking at me in that dark, accusing way she has. Everyone has their own haunting, and she is mine. Tonight, I’m sleeping in a budget hotel in Wellington listening to a category two cyclone throwing an ocean’s worth of rain at the window like gravel. I should be working on a new story, but I haven’t written anything worth keeping for weeks. Mansfield disapproves of my inertia.

‘Shouldn’t you be doing something?’ she says. ‘Don’t you think this is a complete waste of your life?’

She’s holding out a bunch of primroses arranged in a blue bowl. A still life; une nature morte. They smell of the forest, damp moss, undergrowth – The Wild.

‘You know they’ll die, of course,’ she says, arching one perfect eyebrow. ‘They always do.’ And then she vanishes in a waft of yellow broom and white manuka.

Sometimes she brings chrysanthemum blooms floating in a black Japanese dish. Yellow chrysanthemums remind her of sunflowers, a painting by Van Gogh, a new way of writing. On another occasion she brought me purple lilac in a green jug. Lilacs are for grief, she told me, their scent a memory keeper from the time she travelled on a train across Germany, pregnant with the baby that didn’t live. Lilacs are for abandonment. Lilacs are Garnett Trowell.

Once she appeared in a navy blue suit, very elegant, with an ivory marguerite brooch on the lapel, flaunting a daisy ring she said had been given to her by a new lover. I didn’t know whether to believe her, since Middleton Murry never seemed the kind of man to buy jewellery, or to be fond of daisies.

‘The mind I love must have wild places,’ she told me extravagantly, when I asked about the lovers who had, one by one, proved unsatisfactory. There had to be ‘little flowers planted by the wind’, and ‘dark damsons’ bruising themselves in the tangled grass. A cultivated garden was death to creativity, she insisted, impossible to order perfect paragraphs from something already pruned naked.

I’m imagining the motel room on Tinakori Road. I can’t go back there, any more than she could. A global pandemic, not TB this time, keeps me here. ‘You should be writing,’ she says again. But I can’t write, can’t breathe. Pure panic. Mansfield knows all about that.

I let her tell me about Karori, about the wild garden around the house, and the pear trees in the orchard. She talks about the aloe, that flowered only once every ten years. ‘The very essence of truth’. All that fertility, a bud pushing up inside the skull, finding its way out of darkness, shaking the flower free.

The motel is quite close to the Botanical Gardens, now manicured, well managed, but, in Mansfield’s time the gardens were close to the bush, where darker, more disturbing forms waited in the margins of her imagination. They lurked inside her body too, throwing an ink bottle, a book, switching identities from Maori to Pakeha and back. ‘You are a little savage from New Zealand,’ someone told her, and she was pleased.

Neurologists say that the sense which stimulates memory the most is that of scent. A whiff of fragrance can take us straight back to a particular place or time. Mansfield is fond of an expensive perfume called Genet de Fleurie. It takes her back to Thorndon, and the hills where broom and gorse bushes grew like flocks of golden sheep, where she loved to run wild when she was a girl. She has never been so free since.

It’s spring in Europe, and the wild jonquils are seeding themselves among the rocks in the alpine meadows, and swaying in yellow clouds further down in fields grown for perfume. Mansfield is in southern France, mourning the death of her brother. She is alone, once more abandoned, drawing the scent of jonquils into her rotting lungs. By now, a quarter of the population of Europe has died from what her lover refers to as the ‘romantic disease’. In the past it has claimed the Brontë sisters, Keats, and one of Mansfield’s favourite Russian writers, Chekhov, but Mansfield is determined to survive. The elusive Middleton Murry is persuaded to return and, in the market, she buys six bunches of violets to welcome her reluctant lover, ‘in a state of lively, terrified joy’. She rents a house with an almond tree in the garden, economises on food, lives on omelettes and oranges, and is often hungry. Then comes the agony of another parting. Another disappointment. The sound of the gate closing behind her. Pas de nougat pour le Noel.

But now she is experimenting with the word ‘husband’. And she is pale, fragile as the violets she takes from the collar of her coat and crushes in quick, nervous movements. Is he faithful? ‘There are letters,’ she says. They lie on the hall table like fatal white petals.

The scent that takes me home is the astringent smell of sphagnum moss and pine bark, the sweetness of moorland gorse, with bitter undertones of peat. The fox-coloured hills I grew up on were rich with these odours. I wrote my first poem under a larch tree, breathing them in. This was the primal imprint, like Thorndon, or Karori. You can find echoes of it in other places, but never so strong, with so much life in the breath of it.

Mansfield is critical of my poetry and reminds me sternly to remember to be accurate – the exact word – nothing else will do. The ‘detail of detail - the life of life’. She herself is forensic.

‘Colour. Pink. 5 petalled flower with seed purse darker colour, thick reddish stem, small leaf like a bramble leaf. The seed purse is highly glazed, it is – in 3, one long wing & 2 little ones. Attached to it is the 5 petalled flower. It always falls in delicate clusters.’

She frowns at my cheap hotel room. Her life has been a procession of rooms like this, she says; worn carpets, faded roses on the wallpaper, swelling and reddening in the middle of a feverish night. ‘I know I shall die in one,’ she tells me. ‘I shall stand in front of a crochet dressing-table cover, pick up a long invisible hairpin left by the last “lady” and die with disgust’. In a more comfortable hotel in Cornwall, her friend Anne Rice brings a bunch of flesh-and-blood red roses. They bloom in Katherine’s cheeks, on her tongue, and on the white lawn squares she tucks up her sleeves. She tells me about her ideal house, the Heron, which must have a magnolia in the garden, wisteria on the wall, and a medlar tree. And there must certainly be bees.

‘Why flowers?’ I ask her. ‘Why?’ She shows me a moonlit pear tree at the bottom of the garden. It is perfect, but the blossom is already falling, rotting down into the grass, leaving just the promise of fruit.

From a chalet in the alps, drifted under snow, Mansfield erects a marquee in a garden in Wellington, orders lilies and roses, trails her fingers through the lavender that grows beside the path. At the bay she runs to the sea, through blue grass and toi-toi, sea pinks and dew-pearled nasturtiums, swims out into the cold, blue waters towards the snow-tipped mountains of the South Island. Mansfield’s husband talks of nettles and danger, quoting Shakespeare. But it’s January and she has already escaped him.

‘What was it like?’ I ask her. ‘Really?’

She shrugs her shoulders, her face a mask. She’s holding out a notebook that opens to reveal pressed flowers between the pages; petals that still seem to move and breathe in the draught from the cyclone-battered window. She raises another, enigmatic eyebrow. ‘You can still find me here, can’t you?’

And there is Kezia, admiring the moon-white cosmias grown from a 3d packet of seed, now as tall as herself, but ‘frail as butterflies’, their petals fluttering ‘like wings in the gently breathing air’.

© Kathleen Jones 2021