Quinn Reid's Blog, page 8

November 6, 2012

Ten Ways to Detect a Lie or Secret

Body language is like a key to a hidden language: understanding it helps bring out another whole level of communication that isn’t normally visible to us, even though we sometimes react to it without knowing what’s driving our reaction. Of course, one of most the useful applications of understanding body language (as well as speech patterns and facial expressions) is detecting lies. This article offers ten ways to do that.

Body language is like a key to a hidden language: understanding it helps bring out another whole level of communication that isn’t normally visible to us, even though we sometimes react to it without knowing what’s driving our reaction. Of course, one of most the useful applications of understanding body language (as well as speech patterns and facial expressions) is detecting lies. This article offers ten ways to do that.

Unfortunately, body language isn’t as simple as one position or gesture always meaning one thing, but it can provide strong clues to what other people are thinking. Multiple clues taken together can provide a clearer and more definite picture of what’s going on in another person’s mind, especially when we take speech and facial expressions into account.

Sometimes when we hold something back or are feeling anxious, we act as though we’re lying even when we aren’t–so lie detection can sometimes mean just detecting that there’s something hidden, even if the words being spoken are true.

Here are ten indications that someone may be lying:

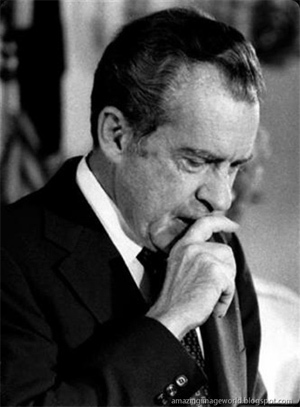

1. The nose touch. When we lie, we have a built-in urge to cover our mouths. However, most of us naturally learn to curb this at a young age because it’s such a clear giveaway. The urge is still there, though, and so the movement often turns into touching the nose or another part of the face.

2. Repetitions and hesitations. When we lie, we are more likely to hem and haw, and also more likely to say something more than once or with more emphasis than it requires.

3. Crossed ankles. This one usually happens when someone is sitting, and it tends to mean that something is being held back or hidden.

4. Looking to the left. When we remember, we’re more likely to look to the right; when we’re making things up, we’re more likely to look to the left.

5. Touching the back of the neck. As funny as it is to hear, touching the back of the neck is often an unintended signal that someone or something is “a pain in the neck.” This move may happen when an unwanted question is asked, or when dealing with something the person considers a nuisance.

6. The mouth smiles, but the eyes don’t. Telling real smiles from fake smiles isn’t always easy, but one of the bigger giveaways is that the mouth may change shape while the eyes don’t move. Real smiles usually include crinkles around the eyes. (See “How to Tell a Real Smile from a Fake Smile.”)

7. The lopsided smile. Real smiles are usually made with the whole mouth. If a smile is lopsided, it’s often not completely sincere.

8. A flash of worry. A “microexpression” is a very brief facial expression that occurs without the person intending or generally even knowing it has happened. A worried or angry microexpression that’s replaced by a happier look can indicate a lie.

9. The mouth says yes, but the head says no. When a person is saying something positive but accompanying it by shaking the head, that’s often a signal that they don’t believe what they’re saying. If the statement is negative, though (for instance “I am not interested”), then a head shake is a natural way to emphasize and confirm.

10. Freezing up. When we lie, we tend to have trouble reacting the way we normally would, and we stop using our normal gestures and maintaining a comfortable person-to-person body relationship. A person who’s lying will usually be more physically awkward and less physically expressive. That’s not surprising: deep down, we know our bodies can give us away, and we may try to shut them down.

If you’re interested in body language, you might like to read some of my previous posts on the subject, which include

How to Tell If Someone’s Interested in You, and Other Powers of Body Language

Body Language for Actors: Common Mistakes

November 2, 2012

Inclusivity and Exclusivity in Fiction: Aliette de Bodard on Crossing Over

This is the seventh interview and the ninth post in my series on inclusivity and exclusivity in fiction. You can find a full list of other posts so far in the series at the end of this piece.

In today’s post, I talk with British Science Fiction Association award-winning French/Vietnamese writer Aliette de Bodard about writing, reading, cultural divides, and the bridges that span them.

LUC: Just to bring your work to science fiction and fantasy readers in North America, you’ve had to bridge a number of gaps–ethnic, linguistic, geographical, and more. Does this affect how you choose your characters and how you think about writing?

LUC: Just to bring your work to science fiction and fantasy readers in North America, you’ve had to bridge a number of gaps–ethnic, linguistic, geographical, and more. Does this affect how you choose your characters and how you think about writing?

ALIETTE: I have to admit that I didn’t quite think of it that way! For starters, I was hardly aware of the SFF market as being sharply compartimentalised when I started writing–and, if anything, I would have targeted my work at the UK market, since that’s where I started reading most of my genre. I also seldom think in terms of gaps when writing: rather, I write passionately about things that matter to me, and trust that this enthusiasm will communicate itself to the reader.

But yes, if we’re talking quite plainly–of course my origins, my personality and the milieu I grew up in and am still part of deeply and irrevocably approach how I’m choosing characters and how I think about writing. I would be a very different person if I had grown up white on the US East Coast–my family, my education, my friends, etc. have shaped me as a writer, and continue to shape me.

I tend to pick characters from non-mainstream backgrounds, mainly because I’m somewhat disquieted by how SF, which should be the literature of the mind-blowing and mind-opening, tends to over-feature characters from a certain background (overwhelmingly male, white and American or Western Anglophone) and from a certain mindset (what I would call “tech-loving” with a strong faith that science will make things better). Not, of course, that I have anything against those views myself, but the over-representation of these can be a little overwhelming in the bad sense of the term…

I approach writing as the sum of everything that I have read, which means traditional French/English/Vietnamese/Chinese literature as well as genre from Ursula Le Guin to Alastair Reynolds to Jean-Claude Dunyach. Reading so much in so many traditions has enabled me to see that the “rules” of writing (like “show don’t tell”) are deeply problematic because they enforce the conformity of a certain type of fiction–they’re a great help as you’re starting out, but taken too rigidly they can easily lead people to stifle their own creativity in the search of the technically perfect, but soulless story.

It’s hard for me to tell how much my approach to writing is shaped by my background and which specific bits are “different”–I know that I place a high importance on family in my fiction, and immigration and living between different cultures (obviously a very personal preoccupation!), but I assume there are more subtle effects on themes, characters and storylines that I’m not able to see because I’m too close to them.

LUC: There are a lot of interesting threads in that response, but let me grab onto one particular one, because I don’t think it’s ever even come up in this discussion for me until now: science fiction tending to include people of a certain mindset. I had never thought of it that way before, but it strikes me immediately as having a lot of truth to it. When science fiction stories emphasize strongly tech- and science-friendly characters, what points of view would you say aren’t getting a lot of representation?

LUC: There are a lot of interesting threads in that response, but let me grab onto one particular one, because I don’t think it’s ever even come up in this discussion for me until now: science fiction tending to include people of a certain mindset. I had never thought of it that way before, but it strikes me immediately as having a lot of truth to it. When science fiction stories emphasize strongly tech- and science-friendly characters, what points of view would you say aren’t getting a lot of representation?

ALIETTE: Hum, it’s one of those questions where I don’t think I can give a complete answer to, but I can provide a few examples… By and large, SF is mainstream US, 21st-Century and tech-loving, which means that anything outside those points of view is getting poor representation. I can mention a few things that struck me, beyond the most obvious ones of poor POC/female/non-US representation, but this is obviously very limited!

the paucity of stories where family is important, and in particular family outside the nuclear family (SF sometimes gets around to mentioning fathers and mothers, but aunts, uncles and cousins somehow seem beyond the realm of possible relationships)

a marked dichotomy between allegiance to a church or allegiance to science, generally failing to recognise either that the two points of view are not incompatible, or that religion doesn’t necessarily mean full allegiance to a church (in many Asian countries, people practise bits and pieces of religions depending on the circumstances, and don’t refer to a single church for prescriptions on every aspect of their daily lives)

a presentation of individualistic, lone mavericks who strike out to seek adventures as intensely heroic, and a deriding of people who do not follow that mindset as being cowardly (in Asian culture, people who abandon their families to strike out would be the cowards because they shirk their duties to provide for their relatives, and the act of falling out with your own family would be a tragedy rather than a cause for celebration).

LUC: Recently on your Web site, you quoted Juliana Qian:

Our cultures are exotic, fashionable, fascinating and valuable when contained within or filtered through a white Western lens – then our cultures are glittering mines. But drawing from your own background is backward and predictable if you’re a person of colour. Sometimes white people try to sell me back my culture and I have to buy it. My China is as much the BBC version as it is the PRC one. There are things I want to eat but cannot cook.

This brings up the question of how different it is for someone within a group–whether we’re talking about, for example, Russians, transgendered people, or people with physical handicaps–to write about that group than for someone outside in terms of how the writing itself is viewed. How does this affect your work, or the work of other writers whose work you follow?

ALIETTE: It’s all but inevitable that someone within a group will perceive it in different terms than someone outside a group: it’s what I call “insider” writing vs “outsider” writer. There are two different problems: who is writing this, and for whom it is intended. I’ll leave aside the obvious combinations of outsider writer for outsiders only (which is a very dodgy proposition and fairly exclusionary) and insider writer for insiders only (posing no particular issue: write what you know for people who know it as well). That leaves the “crossing overs,” i.e., outsider writers writing for an audience which includes insiders and insider writers writing for an audience which includes outsiders.

If you’re an outsider, it is possible to achieve a sufficient degree of empathy with the group to make your depiction of it from the inside plausible, but it takes a lot of hard work, and I think people don’t understand how seldom this happens: the authors who pull this off, say, for Vietnamese culture, can literally be counted on the fingers of one hand, and generally have thoroughly immersed themselves into it for years. A few more authors will produce a passable description, and the bulk will unfortunately perpetuate majority stereotypes or latch onto what seems to them shiny elements of a culture–elements that are totally natural to insiders (one of my favourite examples from Sino-Vietnamese culture includes the over-emphasis on face, which is an unconscious thing–people don’t spend their time going, “oh, I’m going to lose face if I do this” every two lines!). Hence the importance of thinking very carefully about what you’re doing when depicting a culture and of getting beta-readers from said culture to correct you.

If you’re an insider, you have a slightly more difficult problem. I’ve already said that the elements of a culture that appeal to outsiders are not necessarily the ones that insiders think most important, and also that many things that seem natural to you (like food) will require explanation in order to make sense to outsiders. There’s a hard line to draw between making your culture a little more “accessible” to outsiders, and between twisting it out of shape so it appeals to the market.

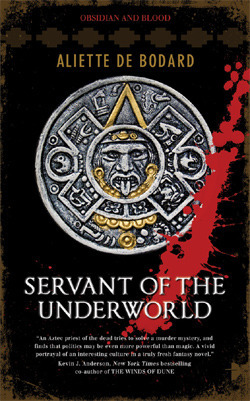

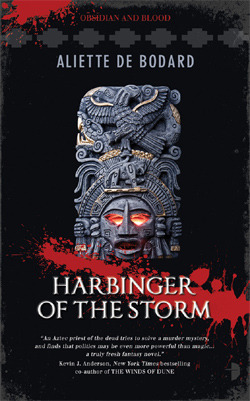

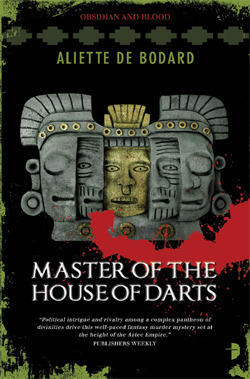

In my work, I’ve done outsider and insider depiction: when I do outsider (such as in the Aztec books), I do my best not to exoticise or demonise practises that the main characters would have found totally natural, like human sacrifices. When I do insider writing, I find myself very often having to explain behaviours and attitudes that are perfectly normal to me, but that make no sense to outsiders (like filial piety or Confucianism): the first draft of my novella “On a Red Station, Drifting” basically had every (non-Vietnamese) reader terminally confused, and I had to do my best to clarify what I meant without having the impression that I was putting the “crunchiest bits” of my culture on display for Westerners (I enjoy writing about my background, but I certainly don’t want the feeling that I’m debasing it in order to sell better!).

LUC: I was interested when you mentioned those authors that you could count on the fingers of one hand, because while we’ve all seen examples of mishandling of other cultures, examples of people who do the job really well seem harder to come by. Are there any writers that come to mind to you offhand who really do an exceptional job, whether they’re outsiders whose writing rings true to insiders or insiders who make a real connection with outsiders?

ALIETTE: It’s going to be hard for me to point out outsiders who really do insider narrative well, as I can’t really appreciate anything beyond France and Vietnam in fiction; and a lot of portrayals of both, as I said above, are very debatable to say the least. That said, one of the works I thought did a great job of evoking the spirit of 17th-18th Century France was Kari Sperring’s debut, Living with Ghosts: the intricate plot and delicately-drawn characters made me think of a modern-day, more nuanced Dumas.

There are more than a few people who are insiders and who create a real connection with outsiders: the first one who comes to mind is the unstoppable , whose fiction is basically everywhere, and who creates really strong stories driven by Chinese culture. I can also cite Rochita Loenen-Ruiz, whose idiosyncratic Filipino SF is bound to make a huge splash (check out her “Alternate Girl’s Expatriate Life“, which tackles emigration, mixed marriages and power dynamics in a very spec-fic way), and Zen Cho, who has a knack for mixing comedy and poignancy in really well-realised stories (her “House of Aunts” is a really awesome not-quite-our-vampires story).

As far as novels go, can I point out to Thanh Ha Lai’s truly awesome “Inside Out and Back Again”, which shows emigrating to America from the point of view of a young Vietnamese girl and the resultant culture shock; and to Joyce Chng’s Wolf at the Door and sequels, urban fantasy set in a vibrant and rich Singapore and featuring a very strong main character in the presence of werewolf pack leader Jan Xu.

Aliette de Bodard lives in a flat with more computers than warm bodies, and writes speculative fiction in her spare time–her Aztec noir fantasy trilogy Obsidian and Blood was published by Angry Robot, and her short fiction has garnered her a British Science Fiction Award and nominations for the Hugo, Nebula and Campbell Award for Best New Writer. When not writing, she blogs and posts recipes over at www.aliettedebodard.com

Aliette de Bodard lives in a flat with more computers than warm bodies, and writes speculative fiction in her spare time–her Aztec noir fantasy trilogy Obsidian and Blood was published by Angry Robot, and her short fiction has garnered her a British Science Fiction Award and nominations for the Hugo, Nebula and Campbell Award for Best New Writer. When not writing, she blogs and posts recipes over at www.aliettedebodard.com7/27 – interview with Leah Bobet

7/29 - Where Are the Female Villains?

8/3 – interview with Vylar Kaftan

8/9 - Concerns and Obstacles (multiple mini-interviews)

8/10 – James Beamon on Elf-Bashing

8/17 – Steve Bein on Alterity

8/24 – Anaea Lay on “An Element of Excitement”

9/21 – Leah Bobet on Literature as a Conversation

October 31, 2012

3 Keys to Living Effectively: Attention, Calmness, and Understanding

A number of my posts in coming weeks will make mention of His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama. I was fortunate enough to hear him speak recently in Middlebury, Vermont, and since then I’ve been listening to some of his recorded public talks, which are freely available along with a lot more interesting material at dalailama.com. Thinking about some of the things the Dalai Lama has said, I found myself faced with a question about my own life: I know a lot about how to act in my own best interests, yet some of the time I act as though I only understood short-term pleasures and not long-term happiness. Why is that?

Based on bits gleaned from psychology, neurology, and meditative practice, I came up with three things I need in order to ensure I act in the best way possible–to encourage my own success while simultaneously letting go of stress, overcoming fear, enjoying what I’m doing, and staying in touch with my highest goals and aspirations. It’s a tall order, and the three things aren’t easy. On the bright side, though, they are simple.

1. Attention

A good habit is a treasure, because it takes no special effort to follow. When I show up to Taekwondo several times a week and get a good, long workout, it’s not because I’m thinking about or planning exercise: it’s because I’m used to going to Taekwondo. In the same way, bad habits are serious trouble. In order to break a bad habit, or even to overcome it on a one-time basis, we usually need to be able to direct attention to what we’re thinking, feeling, and doing. We could also talk about attention as having to do with self-awareness or mindfulness.

For example, I might be tempted to sleep in some morning and risk being late for an appointment. It’s difficult to battle this intention if I’m just thinking about how it would feel to stay in bed versus how it would feel to get up, and especially if I have a habit of sleeping past my alarm. However, if I consciously think about things like

“If I get up now, I can be on time–and if I don’t, I risk being late”

“Staying in bed is pleasurable, but I like showing up on time to things too”

“I’ll have to get up sooner or later, and it probably won’t be any easier in 15 minutes than it is now”

… and other things in the same vein, then I’m able to make a decision rather than just succumbing to my gut feelings.

2. Calmness

Buddhist teaching warns about the danger of attachment, of strong emotion. Speaking honestly, I’m not entirely sure how this applies to strong positive emotions like love or delight, though I could make some guesses. What I am sure of is that getting wrapped up in my own emotions and doing nothing about it leaves me in a position where it’s hard to change or do the things that are best for me. Being able to step back from our emotions and out of a frame of mind dominated by thoughts like “I really, really want that” or “I’m afraid!” or “I feel embarrassed” puts us in a place of calmness from which we can think about our long-term interest and our well-being–not to mention other people’s long-term interest and well being. Not having that calmness keeps us confused and short-sighted, bogged down in an obscuring cloud of emotional debris.

This site offers a wide range of tools for working with emotions, even very strong ones, including idea repair, understanding mental schemas, and much else. If I want calmness, there’s usually some way for me to achieve it.

3. Understanding

I started out thinking of this item as “knowledge,” but I realized that it includes not just understanding how my mind works, having good organizational strategies, and knowing how to keep myself healthy, but also ideas of what’s truly important, what leads to real happiness, what the value of a good relationship is, and what kinds of goals are worth pursuing. Having attention and calmness is not nearly as useful when I don’t have the understanding to use that attention and calmness by making and acting on good decisions.

That’s it: attention, calmness, and understanding. If I can remember to look for those three things, my theory goes, I’ll be on top of the world. I’ll report back and let you know how it’s been working for me. I’d be very interested if you care to do the same, whether in comments or privately through the contact form.

Photo by Hani Amir

October 29, 2012

How Do I Preload Books onto a Kindle I’m Giving as a Gift?

I’m collaborating with a group of five other science fiction, fantasy, and historical fiction authors on a contest that will give away a new Kindle Fire loaded with about a dozen great books. (More on that later, when the contest is ready to announce.) One of the questions we’re deciding on is how we want to give someone a Kindle with books already on it.

This turns out to be kind of tricky. When someone receives a Kindle, they have to register it to an Amazon account. When this happens, according to Amazon, all previous content (whether purchased or manually loaded) is wiped from the device. This means that you can’t just order someone a Kindle and have it show up with the books you want on it, and it also means that if the person who’s getting the Kindle is going to register it, you can’t have it delivered to yourself, manually load up the books, and then give it to that person. This holds true regardless of whether you’re gifting a new or a used Kindle.

Fortunately, there are several workable approaches. Here are the ones I know of. Please note that in most cases, it’s helpful to indicate when ordering a new Kindle that it’s a gift so that it isn’t automatically registered to your account. With a used Kindle, the recipient just has to re-register, in most cases.

1. Amazon gift card

This is the least creative approach, but it’s also the easiest: just buy an Amazon gift card to go with the Kindle. This lets happy recipients choose and buy books on their own. It’s no good if you want to include specific books rather than just suggestions of what to buy, and it doesn’t help if you want to load books that don’t come from Amazon’s store (including, if you’re an author, your own–unless you want to pay Amazon to buy your own books, which considering you receive a 70% royalty in many cases might be a perfectly good option too).

2. Books delivered after the Kindle is registered

This one’s pretty easy as well. In addition to buying the Kindle for your gift recipient, you buy the books, but indicate that they’re gifts and specify who to. Once the new Kindle is registered, the recipient receives those gift books on the new Kindle. Again, this one’s no help if you’re not including books from Amazon itself.

3. Send files

Kindles read not only Amazon’s .AMZ files, but also other formats, including .MOBI and .PRC (general eBook formats that aren’t limited to Kindle books); .DOC and .RTF files from Microsoft Word and other word processors; text files; HTML files; graphics formats like .JPG, .GIF, .PNG and .BMP (not good for reading); and Adobe Acrobat .PDFs. (Regarding .PDFs, a warning: many are designed for 8.5″x11″ paper and have to be shrunk down to a painful and sometimes unreadable size to be shown on Kindle). Any of these non-Amazon file types can be sent or given to the new Kindle owner through e-mail, download, thumb drive, CD-ROM, file transfer, or any other means that you would normally use to send files.

Once received, the files will need to be transferred onto the Kindle, usually using the Kindle’s USB cable. (However, Kindle owners can also use my #4 option, below, to send books and documents to their own Kindles, providing they’ve “whitelisted” themselves as described.)

4. Email via @free.kindle.com

My favorite option for getting files onto a Kindle, because it doesn’t require plugging in a USB cable or even being physically present, is to use Amazon’s @free.kindle.com e-mail address. This is a free (no surprise there) e-mail address provided to every Kindle user by Amazon, and it delivers files and eBooks via a wireless connection. There’s also a @kindle.com address that works over 3G for 3G-capable Kindles as well as over wireless, but documents sent that way are sometimes subject to a small charge to the recipient, so I always stick with the free version.

The one limitation of this approach, which is a sensible one, is that the Kindle owner must pre-approve (“whitelist”) the sending e-mail address before anything can be received this way. All this does is approve the e-mail account being entered to send documents or books to the Kindle, so unless you’re worried about the sender sending a bunch of things you don’t want, there’s no real danger to it. Approved e-mail addresses can also be deleted at any time.

To whitelist a sender, the recipient needs to follow these steps after registering the new Kindle:

Navigate to https://www.amazon.com/gp/digital/fiona/manage#pdocSettings and log in if prompted

Scroll down to near the bottom, where you’ll see a link that says “Add a new approved e-mail address.” Click this link

In the dialog box that appears, enter the sender’s e-mail address.

Click the “Add Address” button

Once this is done, the sender can forward books that will appear automatically on the recipient’s Kindle the next time it’s connected to a wireless network. Note that it takes a few minutes after starting and connecting to the wireless network for the Kindle to check for new items, find them, download them, and display them. Wireless connectivity has to be turned on through the Kindle settings for this to work, of course, but most users will already have it on.

Don’t send books or documents before the whitelisting is complete; they’ll just vanish into the void. Once this process is set up, though, it’s an easy way to get documents onto other people’s Kindles. This can be very handy not only for gift giving, but also for critique groups, work-related documents, sending articles for friends to read, etc. It’s one of my favorite underutilized Kindle features.

Of course, this approach doesn’t work for sending books purchased on Amazon; for that, try one of the earlier methods.

That’s all of the ways I can think of. Did I miss any?

Photo by sundaykofax

October 25, 2012

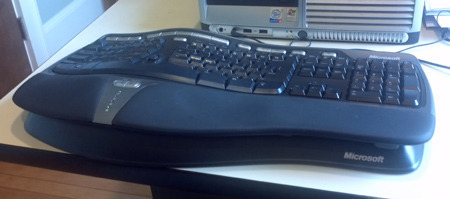

Things I Love: Microsoft Natural Ergonomic Keyboard 4000

Even though it’s not usual fare for this site, I’ve been thinking that it might be helpful for me to from time to time talk about something I have or use that I can strongly recommend. I’ve done this for Scrivener in “How Tools and Environment Make Work into Play, Part I: The Example of Scrivener” and “Would Scrivener Make You a Happier Writer.” Here’s a brief discussion of something you may find useful if you do a lot of typing (I do a lot of typing): the Microsoft Natural Ergonomic Keyboard 4000.

What I like about this keyboard:

It has an ergonomic rather than flat or simply curved layout, which helps me stave off hand and wrist injuries.

The two main sections of the keyboard are split, which makes my hands stay on their sides and forces me to type properly. I learned to type through multi-finger hunt-and-peck, so a little rigor really helps me stay in the groove of typing the “right” way–and thus more quickly and accurately. My typing speed is about 80 wpm on this keyboard, which is a little faster than without it. (After all, it’s important to be able to type quickly if you’re going to write prolifically.)

It has a number of useful buttons and gizmos, like a zoom slider, multimedia buttons, calculator button, Internet button, e-mail button, and a bank of programmable buttons.

Both the wrist rest and the keys feel really nice to me. I’m always a little disappointed when I go back to my older ergonomic keyboard, which I have set up on another computer.

It looks cool as long as you’re into black. I know that’s not important, but it’s nice to have. Who in the name of all that’s holy ever decided that “putty” would be a great color for computer devices?

It’s the only keyboard I’ve ever seen (though I’m sure not the only one existing) that comes with a piece that elevates the front of the keyboard for a reverse angle–instead of angling the keys up in the back like so many keyboards with feet do. My understanding is that lifting up the back of the keyboard is asking for repetitive motion injuries, while a reverse angle is ergonomically ideal.

It’s pretty cheap for a terrific keyboard–less than $40.

I understand and sympathize if you’re one of the many people who’s used to propping a keyboard up in back and/or who is very uncomfortable with an ergonomic layout. About these things, I can just say that my experience was that I got used to the new setup within about a week when I changed over years ago, and I’m very much willing to go through that kind of temporary inconvenience to permanently guard against injuries.

Complaints:

Honestly, none so far. Maybe it would be nice to have an easy way to label the 5 programmable function keys, but that’s just getting picky. It’s a pretty nice piece of equipment for the typing-conscious.

October 24, 2012

Aikido Interviews, #1: Trying to Discover Truths

This post is my first in a series interviewing 3rd degree black belt Aikido practitioner Dwight Sora. While I’m interested in martial arts for their own sake, Aikido strikes me as having some unusual philosophical lessons about acceptance, change, and growth.

Dwight tests for his 3rd degree black belt (Sandan)

Luc: My impression of aikido is that it’s a little different from most martial arts both in techniques and in general philosophy. What’s aikido about, on the most basic level?

Dwight: Ah, the classic $65 million dollar question. It’s one I don’t have a fully satisfactory answer for myself. When I consider what I myself think aikido is, I realize that my perspective has changed radically from when I first started as an exchange student to Japan in 1993. Naturally, I have my “sales pitch” answer to prospective students at the dojo to which I belong: It’s a Japanese martial art, it incorporates empty hand practice and armed techniques involving traditional weapons (wooden sword, staff, dagger), it’s based on a non-aggressive philosophy, you use the enemies energy/movements against them, etc. etc.

Lately, the idea I have been pondering the most is that although I can definitely say that aikido is a martial art, I would not call it a fighting art. Certainly, the techniques practiced and the objectives informing all the movements are drawn from traditional Japanese fighting forms, primarily swordwork and old-style grappling (the same roots of jujitsu and judo). However, I’d be the first to admit that a great deal of our regular practice lacks modern-day utility as a fighting art: We train barefoot, we wear training gear completely unsuited to modern warfare or street fighting, many of our exercises involve a level of stylization irrelevant to strict combat.

I guess one way of putting what I think aikido is, is that it’s a philosophical (and possibly spiritual) study with a strong physical component. Like any philosophical study, you’re trying to discover truths about yourself and the world around you. However, instead of disengaging into a world of your own thoughts, aikido promotes the idea of study through engagement. If meditation is the act of centering yourself while keeping your body still, then I’d say aikido is a way of maintaining that center within while your body moves about.

Now, as I said above, I still definitely say that aikido is a martial art. It’s vocabulary, etiquette, actions, etc. are all drawn from traditions and concepts rooted in the practice of warfare or one-on-one combat. So, I would never put it in the same category as certain types of dance, or practices solely identified as physical exercise.

That being said, I know in my own practice that one gains greater insight and appreciation of aikido when one occasionally explores the fighting aspect. A major part of aikido is the study of kuzushi, of breaking the balance of an attacker, thus facilitating the easy execution of a martial technique. Now, from what I can gather, a person with absolutely no interest in fighting could possibly focus all of their aikido study on this aspect, simply to study how to keep their body relaxed and stable, and how one can adjust their posture and movements in a way that affects a training partner engaged in movement. In turn, this study could be effectively practiced simply with basic grabbing of the joint targets (wrists, shoulders, etc.), skipping over punches, strikes or kicks. The result would be very much like the study of pushing hands in Tai Chi, or a kind of two-person interactive yoga.

However, for myself, actually studying the vulnerable points of one’s body and an opponent’s as they move in reaction to each other, the lines involved in executing a punch or strike, will aid in the study of the above, which is mostly focused on aikido’s internal aspects.

I think the points I mention above are why there are such radically different approaches to aikido depending on the school or teacher. There are some who take an extremely martial approach (like Steven Seagal) and insist on emphasizing the fighting aspects. Others (such as the Ki no Kenyukai or “Ki Society” of Koichi Tohei Sensei) really de-emphasize the martial part and give pre-eminence to breathing exercises, centering drills and seeking to achieve a solid mind-body equilibrium.

I think the trap that some people who practice aikido fall into (and the reason that occasionally we’re the butt of jokes from other martial artists) is that some people think they are practicing afighting art, when their training has not really provided them with any such skills. By way of analogy, I ask you to consider a championship Olympic fencer. Fencing, though a competitive sport while aikido is not, shares with aikido roots in traditional forms of fighting. However, if I was to somehow transport the greatest 21st century fencer back to Renaissance Europe and force him to engage in a duel with live blades, he’d probably be killed very quickly. Sure, he can whip a foil around with incredible dexterity, but that’s a world of difference from being placed into a situation involving life-or-death combat without the comforting presence of judges, referees or movement restricted to a plinth. However, that does not detract from the fact that fencing is excellent in developing a keen eye, fast reflexes, a sense of balance – qualities that could both serve someone well in fighting, but also might simply be good in general self-development.

One other thought I have is that I have met some real fighters, and by that I mean combat-experienced soldiers, not people who won tournaments or participated in MMA, who study aikido, and they are among the most focused and centered students of the art I have ever known. And whenever I have felt doubts about whether there is value in studying a martial art which seemingly contains so much ceremony and abstraction from the physical realities of combat, I think of them. Because despite the fact they truly know how to kill another person, and in some cases have done so, they have found something inherently enriching about studying aikido.

October 19, 2012

Writing Naked: How to Profit by Embarrassing Yourself

The original version of this article first appeared in my column “Brain Hacks for Writers” over at the online publication Futurismic. I’m editing and republishing each of my BHfW columns here over time.

Ever have one of those dreams where you’re naked in public? Writing fiction is a bit like having a dream, and some writing is embarrassing because it lays us bare.

I’m talking about the kind of writing where you say something to the entire world that you would prefer not to mention to anyone, just because you want to tell a meaningful story. Or you do something in the story that has very little to do with you personally, that means a lot in the piece you’re writing, but that embarrasses you because you don’t want anyone to think it’s autobiographical.

No, no — that’s not about me!

Let’s dwell on that second situation for a moment, being worried that people will think you’re writing about yourself when you aren’t. This can come up with truly horrible characters—the child molester/serial killer in The Lovely Bones comes to mind—with sexual behavior or fetishes, with gender identity and sexual preference … Looking at my own work, for instance, I find a modest number of stories about lesbians but very few about gay men (though I’ve written both). Like a straight actor who’s offered a gay part in a production, straight writers may not want to be assumed to be gay by the general public. Yet there are times when a gay man would be the best choice in a story, or where a BDSM fetishist (if we’re talking about sexual behaviors) or a male-to-female transsexual (if we’re talking about gender identity) would probably be the ideal thing. Yet for me, my own concerns about what people assume get in the way, even though I’m unconflictedly in support of the LGBTQ community and wish that more fiction were written about non-straight people.

My writing might also be stronger if I were more willing to write characters who are racist or sexist or prejudiced in some other way I find repugnant: certainly you can’t write The Lovely Bones or To Kill a Mockingbird or The Silence of the Lambs without sharing some contemptible characters with the world. Even Holden Caulfield’s bouts of ignorance and trouble with depression in The Catcher in the Rye require that kind of commitment from the writer.

So, note to self: man up and stop worrying about what people will think.

My hope is that most intelligent people understand that there’s a difference between the author and the characters — but even if that’s not true, I care less about what people think than about what my writing does to them. If you haven’t written about people you’d cringe to have identified with you, maybe it’s time to try — just a rough draft of a short story, filled with characters who really interest you but who might embarrass you. The story can be deleted or shredded afterward if necessary — although often it seems to be that stepping up to a fear drains it of its power, so perhaps you’ll surprise yourself.

Pay no attention to the man behind that story!

The other kind of embarrassment, being embarrassed by what you reveal, may be a surprisingly rich source of material if you haven’t mined it before (or haven’t mined it lately). After all, the things we like least about ourselves are some of the most cathartic things to read–and possibly write–about. What would Hamlet be without Hamlet’s suicidal rants, his anger at his mother, and the horribly stupid mistake of killing his would-be girlfriend’s father through a curtain? I don’t know for certain how closely Shakespeare himself identified with these kinds of elements, but he clearly understood what it was like to be jealous, what it was like to be depressed, and what it was like to make a stupid mistake that ruins your life.

This kind of embarrassment can also be therapeutic. There are few things in this world more comforting than facing a fear and finding out you can best it–that there’s no need to avoid it any more, if there ever was.

Must … maintain … illusion … of competence …

While I’m on the subject of fear of embarrassment, let me touch on one last kind: fear of being seen as incompetent. As writers, we’re likely familiar with the kinds of stories and voices people generally accept in modern fiction, and it’s pretty normal for us to produce something more or less in the same vein. Trying things that are strange and bizarre, that we have no way of knowing whether people will like, is much harder. Yet ground-breaking work often comes from writing things that would be more than a bit embarrassing if they failed. Alice in Wonderland, if it weren’t full of genius, would be creepy beyond belief. If Watership Down had failed, Richard Adams probably would not want his eventual epitaph to be “He wrote about bunny rabbits.” Kurt Vonnegut broke writing rules left and right, though fortunately he was brilliant at it, since his stories would be laughably bad if they weren’t supported by skillful writing.

So there lies more encouragement to stretch and embarrass ourselves, because groundbreaking fiction is often the kind that stands out in a potentially humiliating way. What’s the worst that can happen? We’ll be laughed out of our writers’ groups? Laughed out of polite reading society? Enh, I’ve been laughed out of places before. It’s no fun, but it’s rarely fatal.

So let’s get embarrassed! Um … you first.

Photo by Shucker

October 18, 2012

You, Me, and the Dalai Lama

This is the first in a short series of posts arising from the Dalai Lama’s recent visit to Vermont.

So the Dalai Lama walks into the room, and he says “I always consider we are the same human being. Physically, mentally, emotionally, we are the same. I believe it is extremely important we have this feeling or concept–oneness of humanity–because a lot of problems are essentially our own creation.” (Note: I’ve paraphrased that a little.)

The room was kind of a large one–actually, an arena. The Dalai Lama was speaking at the Nelson Recreational Center in Middlebury last Saturday. I sat about 60 feet away, close enough to exercise my dazzling photography skills and get this fuzzy phone cam shot you see to the left. If you’d like to watch the event for yourself, there’s good video footage of the whole thing here, courtesy of Middlebury College.

The room was kind of a large one–actually, an arena. The Dalai Lama was speaking at the Nelson Recreational Center in Middlebury last Saturday. I sat about 60 feet away, close enough to exercise my dazzling photography skills and get this fuzzy phone cam shot you see to the left. If you’d like to watch the event for yourself, there’s good video footage of the whole thing here, courtesy of Middlebury College.

Getting tickets for this event was like trying to get into a sold-out rock concert. The morning the tickets went on sale, I got up early, went to my computer, and sat there pressing the refresh button until the ticket purchase page finally showed up for me, 45 minutes later. I believe their servers were a little overwhelmed. This investment of time and button-pushing was nothing compared to what I received from the experience. One of the things I received was some glint of understanding of how you and I the Dalai Lama are the same.

There’s some obvious truth to the idea that we’re the same: after all, we’re all human. We all have human frailties and limitations, and we have commonalities that range from our natural environment and the air we breathe to literature to neurotransmitters to basic needs to genetics and history. According to Buddhist thought (at least, according to my very limited apprehension of it), any distinction between two humans is arbitrary. There is no clear line of division.

Yet it’s hard to make much use of that idea when you compare how most of us deal with the world to how the 14th Dalai Lama deals with the world. He faces very difficult truths with compassion and humor. He tells hundreds or thousands of people about peeking in someone’s medicine cabinet even though he knew it was, in his words “a little illegal,” or about regretting how he spent much of his youth, and he laughs at himself with genuine mirth and acceptance. For most of us, accepting the worst things about the world or ourselves is a lot more challenging than that. Even on our best days, most of us can’t come near radiating the joy and compassion that comes from the Dalai Lama.

So I have to conclude that something does separate us, something worth knowing about. I think I finally began to get a clue as to what that thing was when His Holiness was answering questions at the end of the presentation. Someone asked him about the problem of dying with awareness when the norm these days is often to pump dying individuals full of pain medications. In response, the Dalai Lama said

That I think … we have to examine case to case. Those individuals who have some sort of … practice and experience, then it is very, very important to keep sharp mind … clear mind.

The word that struck me here was practice. There’s no question that we’re just as human whether or not we’ve spent time meditating or trying to be more aware of ourselves, but having a meditation practice, working hard at understanding ourselves, taking time each day to think about who we are and what we’re trying to do in the world–these things allow us to access different moods, different behaviors, different reactions–an entirely different side of ourselves. My impression is that the Dalai Lama has worked diligently for many years to develop this side of himself. I’ve worked much less diligently for much less time, and perhaps the same is true of you. Yet there is nothing stopping either of us from realizing that side of our humanity, so that we’re not just one with the Dalai Lama, but also are increasingly able to see the world in the same way he does.

Top photo by Sarah Harris

October 12, 2012

There’s Always Another Way to Write It

The original version of this article first appeared in my column “Brain Hacks for Writers” over at the online publication Futurismic. I’m editing and republishing each of my BHfW columns here over time.

In Star Wars: Episode I, Qui-Gon Jinn quips “There’s always a bigger fish.” Admittedly he’s wrong, because since there aren’t an infinite number of fish in the universe, so one fish or group of fish has to be the biggest. And I’m probably wrong too when I say “there’s always another way to write it”–but as with the fish thing, it appears that it’s a rule that’s always accurate.

In Star Wars: Episode I, Qui-Gon Jinn quips “There’s always a bigger fish.” Admittedly he’s wrong, because since there aren’t an infinite number of fish in the universe, so one fish or group of fish has to be the biggest. And I’m probably wrong too when I say “there’s always another way to write it”–but as with the fish thing, it appears that it’s a rule that’s always accurate.

What this means for writers is that there are hidden solutions to almost any writing problem.

Much, Much More Flexible Than We Thought

There’s a book called Le Ton Beau De Marot: In Praise Of The Music Of Language by a brilliant but strange guy named Douglas Hofstadter. Hofstadter wrote this entire 832-page tome about the problems of translating a single pretty-good-but-not-amazing 16th century French poem. The thing is, like many decent poems, “A une Da-moyselle malade” (“To a Sick Young Lady”) has a very specific meter, rhyming scheme, interplay of meanings, etc. Since English, while closely related, is definitely not French, it’s impossible to accomplish everything the original poem accomplishes in an English translation … or is it? What Hofstadter goes on to show, with examples from a wide variety of translations by friends and colleagues, is that if you try hard enough, you can come up with a way to manage almost anything you want with language. This is especially true in English, with its enormous vocabulary.

I don’t know if this is rocking your world the way it did mine: maybe the full power of this fact doesn’t hit without 1) reading through the book, 2) becoming convinced that there’s something that simply can’t be accomplished in English, and then 3) reading an example that does the impossible thing and three other things at once. The moment where Hofstadter really got his point across to me wasn’t in the translations, though: it was when, about 200 pages in, he started talking about using nonsexist language while also steering clear of the awkward but more respectful “he or she” (or “she or he,” as I tend to write it). If you’ve ever tried to write nonfiction with these restrictions, you may have a reaction something like mine: that’s a great idea, but it’s next to impossible.

Then Hofstadter points out that he has written the entire book in non-sexist language without ever using “he or she”–and I had never even noticed! As difficult as that job sometimes seems, Hofstadter can do it so comfortably that it’s completely invisible.

I can’t change that: I need it

I was corresponding with a writer friend recently about a very engaging book he’s writing, and we were talking about a lump of text early on, an important quotation. I suggested that the text didn’t work well as is, and he agreed, but said “I will have to split it up, but I can’t really alter it … I need it for the end.”

Now, “need” is a red flag word for me in everyday life, writing aside, because it often indicates a “broken idea” or “cognitive distortion”, which is to say the kind of thinking that generally doesn’t get us anywhere and makes us miserable. In writing, there’s a similar issue: we may get it in our heads that something has to be a particular way without ever questioning that assumption. In my friend’s case, it’s entirely possible that it’s best for that chunk of text to remain exactly as it is, but does it need to? Our options as writers are practically infinite–is it possible there’s really no alternative whatsoever that still works with the entire story if he were to change that text?

This is the kind of thing that we can tend to get caught up in when we’re writing: “I know that part is kind of boring, but Ihave to get that information in so that people will understand the rest of the story” or “It would be great if character x had a change of heart here, but she isn’t like that,” or even simply “I wish I could try that, but that’s not how the story’s supposed to go.”

Alexander the Great and Indiana Jones

It’s easy to make ourselves think that some piece of our book–a character, an event, the way events are presented, a description, dialog, whatever–has to be the way that it is, but the fact of the matter is that virtually anything could be changed in a way that doesn’t harm or even improves the story. This doesn’t mean that we have to rethink everything we come up with, of course, but it does mean that any time we find ourselves obstructed by a decision we’ve made or a chunk of writing we’ve done, it helps to step away from that and think for a minute about the other ways we could tackle the same thing. If it doesn’t seem possible, it’s often worth actually giving an alternative a try to see if it somehow works out anyway. There is virtually always a different word, a different character twist, a different event that can do what we want it to do if we work hard enough to find it. And practicing this is practice writing differently, which gives us flexibility and fluidity and options.

These kinds of possibilities are a challenge to us to write better, to do more things at once in our writing. Frankly, my feeling is that we need all the advantages we can get. As the writing world gets harder and harder to predict from a business perspective, the only advantage we can really control much is how good we’re getting at writing itself. Being able to cut the Gordian knot (Alexander the Great) or shoot the scary-looking guy with the sword (Indiana Jones) is a good skill to have, and the only time it’s not available to us is when we’re facing that one, biggest fish–at which point, honestly, translating French poetry wouldn’t have saved us anyway.

This was supposed to be a sword-vs.-whip fight, but Indiana Jones makes my point for me

October 9, 2012

Organization: Where Do I Start?

Recently I pulled together some key ideas to use when getting organized into a post, “Organization: Useful Principles,” and I promised to follow up with links to organization posts on this site and with a book recommendation.

I’ll start with the book recommendation, which is David Allen’s Getting Things Done. Allen offers an extremely well-designed approach to organizing task lists and taking care of items on that list: you can get more information on his book in my post “Useful Book: Getting Things Done.”

As to articles on this site, here are some that I hope you might find especially useful:

Task organization

Don’t Use Your Inbox as a To Do List

Weed Out Task Lists With the 2-Minute Rule

My Top 1 Task

Why Tasks Lists Sometimes Fail

Attitude and emotions

Effective Organization and Filing Are … Fun???

Relieving Stress by Understanding Your Inputs

4 Ways to Make Sure You Get a Task Done

Organizing papers

Why bother organizing papers?

The Eight Things You Can Do With a Piece of Paper

Decluttering

Digging Out, Cleaning Up, Uncluttering, and Getting Organized: Let’s Start With a Link

What Our Garage Sale Taught Me About Decluttering My Mind

Some Tips for Getting Rid of Things

E-mail

How I’m Keeping My E-mail Inbox Empty

Free Online E-mail to Help You Keep a Clean Inbox

My Empty E-mail Inbox, 10 Weeks Later

General principles

Organization: Useful Principles

How Exceptions Cripple Organization

Why Organization Improves Motivation, and Some Organization Tips

Little by Little or Big Push?

Photo once again by Rubbermaid Products

Quinn Reid's Blog

- Quinn Reid's profile

- 6 followers