Quinn Reid's Blog, page 9

October 5, 2012

Better Writing Through Writing About Writing

The original version of this article first appeared in my column “Brain Hacks for Writers” over at the online publication Futurismic. I’m editing and republishing each of my BHfW columns here over time.

My life is fairly crammed, and writing time is hard to come by. Today I got one of those precious blocks of time in which I could write for several hours almost without interruption, yet as I fired up the computer, I felt not excited about the prospect, but worried and on edge. I also felt a little unsure: I had several projects I could be working on and was waffling on which one to choose.

Looking before leaping

I could have just plunged in and begun working on whatever seemed easiest, most obvious, or most attractive, and if I got deeply enough into the writing that I achieved flow, that might have gone well. On the other hand, I might have made a bad choice out of inattention, and it’s possible that even if I’d made a good random choice, my concern that I might be working on the wrong thing or my general unexplored discomfort might have seriously interfered with my ability to focus. Under those conditions, I might be especially unlikely to enjoy the work, which is a problem, because while common sense suggests that it doesn’t matter to productivity whether you enjoy the writing or not as you do it, in truth not enjoying what we’re doing tends to make us quit sooner, latch onto distractions more easily, feel less positive about what we’re achieving, and avoid coming back to do more. Liking the process of writing is a good way to write more and to be more invested in our work.

Schema journaling

So instead of starting by writing, I started by writing down my thoughts about writing. One of my current projects is a layperson’s book on mental schemas. Mental schemas (the habitual patterns called “early maladaptive schemas,” if we want to be more technical) are persistent ways of thinking that tend to interfere with living a happy and productive life, explored in detail in a branch of psychology called Schema Therapy. To provide a framework for making use of these ideas in my book, I’ve been experimenting with something I call a Schema Journal, where daily entries are an opportunity to find focus, work through confusing situations, reflect on progress and obstacles, and find answers to difficult questions. This same approach can be used without keeping a journal to sort out any situation that seems to be interfering with writing, whether it’s intellectual (like choosing which of two projects to pursue), emotional (like feeling worried that a project isn’t going well), or organizational (like having trouble finding time to write).

Schema journaling tools

Just writing freely about problems is a good approach, but it can be especially effective to write to a specific purpose. Here are some of the available tools or purposes writing about writing can have:

Feedback loop: Reflection on how behaviors and choices are affecting a situation so far, identifying improvements, and coming up with specific plans to use those improvements at the next opportunity.

Exploration: Thinking in detail about an opportunity or problem to come up with more specific questions or goals.

Decision: Making a choice. This is the kind of entry I used today, starting with the question “Which of my writing projects should I work on at the moment?” This came after realizing that what was holding me back from feeling enthusiastic about writing was that I was conflicted about which project to work on. If I hadn’t been sure what the problem was, an “Exploration” entry would have been the thing to do first. That would have led me to the question I could use for my Decision entry.

Assignment: Choosing a task that is usually avoided and setting a specific time frame for getting it done. This shouldn’t be a big project, but rather a specific thing you can accomplish, preferably in one attempt. Ideally this is something you can repeat, for instance “Choose a short story that needs a small amount of editing, edit it, and send it out.” The writing to do about the task is whatever is needed to create enthusiasm and get focused.

Envision: Visualize a future situation that helps motivate you. The situation should be plausible, but doesn’t have to be something that’s immediately realistic. Getting used to the idea that things could go well and allowing ourselves to feel some of the emotions we experience when things do go well can help create a more positive and focused mood for writing.

There are additional kinds of entries in an actual Schema Journal that are more involved and have longer-term intentions, but the five specific tools above offer ways to get past the emotions, complications, and mental obstacles that prevent writing from getting done, or sometimes that simply get in the way of enjoying the process.

October 4, 2012

Organization: Useful Principles

A reader got in touch with me the other day asking about where to start with task management. While I’ve written a number of articles about different kinds of organization, I don’t believe that I’ve ever tackled the question from the basic question of where to get started with organization as a whole … so here that article is.

Five kinds of organization

At least five kinds of organization can demand our attention, and it’s helpful to separate them in our minds, because each one requires a slightly different approach. Those kinds are:

tasks (anything that needs to be dealt with, from a quick decision to a massive project)

paper (including mail, reference materials, the kids’ schoolwork, bills, receipts …)

physical clutter

information (I won’t go into this in any detail in this article, but see “Eight Ways to Organize Information and Ideas“)

Useful principles of organization

Some approaches to organization are much more successful and rewarding than others. The following ideas can help move things along:

Have a clear system for decisions – It’s much easier to get through a pile or list of items if you have a strict and clear way to deal with them. A detailed working example: if you’re dealing with a stack of papers (or even boxes upon boxes of papers), take a look at the system outlined in “The 8 Things You Can Do With a Piece of Paper.” Process one item, then go back to the top and repeat for the next one.

Don’t get bogged down when planning – One of the difficulties with, prioritizing a task list or clearing out an e-mail box, for instance, is that it’s easy to get bogged down trying to do one specific item instead of finishing the task of organizing all the items. Except for one situation I’m about to mention, it tends to work best to only organize when organizing–not getting sidetracked onto one specific item, no matter how appealing or pressing that item might be (short of an emergency).

Do very quick things right away – Whenever we’re organizing and we come across a form that can be filled out and readied for the mailbox in a few minutes, or a task that will take a very short time to complete, or an e-mail that can be put to rest with a two-sentence response, taking care of that task immediately shortens the to-do list or stack of papers or list of e-mails to handle, and it saves time having to organize and review the item. This is the exception to not doing tasks while planning, because these short tasks won’t bog things down.

Categorize & prioritize – It’s great to get down a list of everything that needs to be done, but if we don’t prioritize tasks then we’ll end up doing whatever seems most appealing, easiest, or most obvious instead of whatever will make the greatest positive impact. Categories make it easier to attend to one kind of thing at a time, and priorities are essential for repeatedly answering the question “What’s the best thing for me to be doing right now?”

Review regularly – When organizing tasks and e-mail, regularly going over the lists is an important part of organization in order to remove things that have been completed, bump up the priority of items that have become more urgent, recategorize, and revisit pending items that have gotten stalled. Along with the obvious benefits of this practice, doing regular reviews also helps us have confidence in our own organizational systems. If we just sweep things into categories and never look at them again, then we’ll our system will start failing this, and knowing this, we’ll be reluctant to put important items into it. As soon as we start keeping things out of an organizational system, that system has failed: it then needs to be handled differently, re-energized, or revamped.

Organize items once – When an item comes into an organizational system, it’s important to make a decision where to put it then and there. If we set things aside to consider later, then later we’ll just be faced with the exact same choice. By making the choice with each item as it comes up, we can make clear forward progress.

All tasks should go to one place – It’s easy for tasks to start growing, like weeds, in many different places. Apart from very basic separations like “work tasks” and “home tasks,” though, that way lies confusion and failure. If I have a computerized task list, a handwritten list for some other tasks, a file on my computer for some other tasks, a few sticky notes, and some e-mails in my inbox that I want to use as reminders, then I have no way to look at all of my tasks together and prioritize them, which means that my system can’t tell me the one thing I need to do next–and a good organizational system can always answer the question “What should I do next?”

In a follow-up post, I’ll provide links to some of the most useful organizational articles on this site and talk about the one book I would recommend above all others for getting organized.

Photo by Rubbermaid Products

September 27, 2012

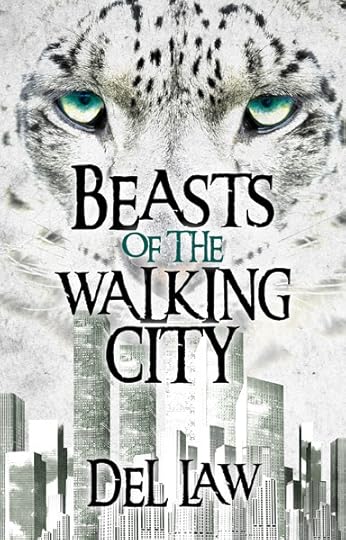

Interview with Del Law: World Building and Character Building in Beasts of the Walking City

Recently I had the opportunity to read Del Law’s debut novel, Beasts of the Walking City, and between the world-building, the characters, and the hard-driving plot, I was engrossed from beginning to end. Since I know Law, I asked him if I could interview him for this site, to get a better idea of how he pulled off this surprising and entertaining story. He agreed, and here is that interview.

Del Law can be found online through his blog, House on Bear Mountain.

Del, what immediately jumps out at me about

Beasts of the Walking City

is the huge amount of world-building–actually,

worlds

-building might be more accurate, since the story takes place in a world that overlaps with a number of others. You’ve created geography, very distinctive types of magic and combat, multiple political groups, various kinds of sentient beings, cities, and history behind all of it. Where did the world of your story come from, and how did it get so detailed and layered?

Del, what immediately jumps out at me about

Beasts of the Walking City

is the huge amount of world-building–actually,

worlds

-building might be more accurate, since the story takes place in a world that overlaps with a number of others. You’ve created geography, very distinctive types of magic and combat, multiple political groups, various kinds of sentient beings, cities, and history behind all of it. Where did the world of your story come from, and how did it get so detailed and layered?

I’m dying to say I found it all behind a back door in an alley somewhere in Hoboken, but no: I’ve been developing Blackwell’s world for a long, long time, almost as long as I can remember. I played role playing games in elementary and early high school and caught the world-building bug then–as a teen-ager I covered walls of my room with maps and sketches of worlds and characters. I bet if I were able to find those maps and dig some of them out, that aspects of Kiryth would be in them, though it’s grown and changed and morphed many, many times since those years. Versions of some character showed up in my undergraduate writing thesis, but even then they were very early versions, written about by a writer who (I think) was still working to find a voice.

I daydream when I can. I try and look at things from strange angles. When I travel I try to find small details that imply a whole lot more behind them. I watch my kids and how they see their world. I try and write it all down and layer it in somehow.

So much modern fantasy is based on our own history here on Earth, and for good reason–it’s a shared reality we all know parts of, it’s easy for a reader to connect to, and by reading or writing books set in different aspects of our world, we all learn more about the world while enjoying a good story. Plus, it’s easier as a writer to not have to make everything up, and if someone’s writing on a deadline you need to get your book done.

But with Blackwell’s world I didn’t want to do that. I wasn’t on a deadline, and I wanted to build something from the ground up, something unique, with characters that feel vivid and real and embedded in social and political contexts as we ourselves are. I wanted it to feel real and dirty and as messed up as our own world often is, not simple and contained. I suppose I cheated a bit by then connecting it all with Earth, but by doing that I got to layer some of our history and details up against the ones I made up, and I think that gives the histories and the characters even more a sense of ‘real-ness’.

At what point did your main character, Blackwell, emerge, and how did you create or develop him?

Blackwell emerged over time, really, and for such a big guy he was pretty quiet about it for a while. I know some writers say they have characters that stick in their heads and sort of lead the story along–not me. I knew I wanted to write from a non-human perspective, since that doesn’t happen very often, and plus it’s a nice way to bring in more detail about the world. But all the standard fantasy races were out for me–overdone, not much room left for originality.

So along came the Hulgliev. Aspects of them came out as I was working through the drafts: once a pretty big deal, now pretty rare. Hated by many–but why? There’s a mystery. They can pigment themselves like a squid does–that’s pretty cool.

But if the book was going to work, Blackwell really had to stand out with a strong voice, and he had to be someone that you could relate to, and not all-powerful or all-knowing. I rewrote big sections of the book and things started appearing. His really bad childhood. His complex family structure. His fondness for bourbon and noodles (things I can relate to). His impulsiveness and poor self image and general naiveté. His desire for something better for himself and his friends. All of these things emerged as being pretty central to how the plot plays out in the book, so there was a lot of juggling to manage it all. I rewrote a lot to try and get it right.

In the end, for me, he was fun to spend time with, as was Kjat, the woman who’s in love with him (though he’s pretty blind to it). I hope they’re both intriguing for readers, too.

So Blackwell emerged in rewrites, a little at a time. I’ve had that happen myself, but it’s not an approach we hear talked about much, even though it seems here to have been pretty successful. Did other important elements of the book present themselves in the course of rewrites as well?

Del Law

Yes, completely. Al Capone came late, and he’s pretty critical now, but early drafts didn’t have him and I think the story was more limited as a result. Fehris, one of the important secondary characters, became not-quite-human as drafts progressed, to make him more compelling. Some of Kjat’s backstory, and how that’s tied to Blackwell’s life, came later. A lot of the smaller details that give the world a broader context tended to come later, too: the Singing Dragon of Barakuu, or the Bakarh Contest of Symmetry, say. This book doesn’t go into them in any detail, really, but the fact that the reader hears of them, knows that there’s something with this kind of mysterious name to it is out there, makes the world feel bigger. (Unless you overdo it, and then there are just too many names and details flying around.)

Some of this comes from me knowing my own strengths and weaknesses, and how to work around them–I’m less great at plot, so I try and work that out first. I’m better at description, so knowing that, I can give myself the leeway to push this off a little while I get the plot pinned down. But then there are cool ways that descriptions interact with and affect the plot–you have to be perceptive enough to roll with that, even when it means a lot more work to get it all right.

The Amazon reviews so far have been overwhelmingly positive, but it’s notoriously hard for new novelist to get much attention for a new book. What future do you see for the Walking City series? What are the chances of a seeing a sequel in the next year or three?

I think there’s a great chance of another book. I’m working on it now, though it’s hard to say how long it’ll take. I don’t want to rush it out and have something I’m not happy with. But there’s a lot in Blackwell’s world that I didn’t touch on in the first book.

Funny, your question came in the middle of a big promotion weekend I’m running on Amazon.com for Beasts. The book was available for free, and was on the top 10 lists for both free Fantasy and free SciFi, and closing in on the top 100 overall free books for Kindle. Hundreds of people were downloading it every hour. For me, that’s totally cool, great publicity, and I think Amazon’s created a great opportunity for early authors to get their work out there. [Note from Luc: As of this writing, Beasts of the Walking City remains in the top 10,000 Kindle books, outdoing a great many novels released by traditional publishers.]

Will it make a ton of money? Probably not this month. But that’s ok for me right now. I’d rather get Beasts out into the hands of readers, give them a chance to get interested in the series, and that’ll give me even more reason to write more of them. Unlike writers who are working for a big publishing company, I can afford to be patient–my book isn’t competing for bookstore shelf space, doesn’t have just a few months in which it has to sink or swim. Beasts can gain an audience slowly, over time, and that’s just fine. I’ll be working on the next book, and the one after that.

September 26, 2012

Practical Takeaways from Running Our Garage Sale

Recently my family, through energetic effort, ran a garage sale from our home in a semi-rural part of Vermont. Running that sale taught me some useful lessons in best (and worst) garage sale practices, and especially seeing as I don’t expect to want or need to run another one any time soon, I’m passing this information on in hopes that it will be useful to you.

I’ve talked in the past about getting rid of things we don’t need and about the personal and emotional side of garage sales. This post, by contrast, is about simple, pragmatic stuff.

We aren’t exactly in a high-traffic area, and the sale was only modestly successful, but it was a useful and necessary step to clearing out a lot of things we’d identified we didn’t need. In the weeks since, we’ve been donating items to appropriate places, putting them up on eBay, and both selling and giving them away through Craigslist. We’re getting close to the end of the process, which is exciting: that will mean we’ll have our garage back, just in time for winter, and I’ll be more clutter-free than I’ve been in many a year.

Signage is essential

Signs were especially important for our sale because our house isn’t visible from the road, and because the road we’re on isn’t a busy one. Accordingly, I made the extra effort to make five sets of signs: one at the intersection with the nearest large road, two directing people down our road from the medium-sized roads that connect with it, one at the end of our driveway to direct people in, and one at the fork in our driveway so that people wouldn’t end up at our neighbor’s house instead (we share a driveway with our neighbors). All of that appears to have been good thinking: I think we needed those signs to guide people in.

Unfortunately, the signs I initially put up had not one, not two, but three significant problems:

They were too small

They had too much information on them, making for small print and too much to read while driving by

The poles they were mounted on weren’t strong enough

I got some poles that looked much sturdier than they turned out to be, and it was a windy weekend, so my signs were sometimes getting blown over. I ended up going out and reinforcing several of the sign setups, but even then it turned out that a key sign was down for the entire sale, which probably lost us a number of customers.

The signs were small because I tried to get away with what I could easily make with a standard printer, and I used 8.5″x14″ paper. What I needed instead were big, bold signs that listed the days, the times, and had an arrow pointing in the right direction with the words “garage sale.” I added some bigger signs for the second day, which helped a little, but I believe that big, clear signs that wouldn’t have blown down would have paid for themselves many times over.

Vendors can’t be choosers

I figured that since we were running the garage sale, we could do it on our terms. Consequently, I set it to run only one day, insisted on no early birds, and declared all prices final. This simply didn’t work. Maybe it works if you have a ton of traffic and people are fighting each other to buy your used coasters, but it’s no good if you live in the woods. We added a second day, lifted the “no haggling” policy, and got more flexible. After all, our goal wasn’t to run a business, but to get rid of some stuff and get a small amount of money back for it.

Free advertising is good

One place I think we made good decisions was in advertising. We posted the sale on Craigslist with a list of many of the kinds of items we were selling (and later, some pictures); on Facebook; and on our local Front Porch Forum (frontporchforum.com). Ads in local papers would have been prohibitively expensive, and offhand I don’t know of any other sites that would have gotten the word out well–though if you know of any, please mention them in comments.

Bargaining rules

No one in my family is an enthusiastic haggler, so I set some bargaining rules to make bargaining more comfortable for me. People who were buying multiple things could get more slack than people buying a few things. Things that I was pretty sure I could sell for more on eBay if I were willing to take the trouble weren’t very negotiable. We had set prices pretty low from the beginning, so I didn’t take less than about 80% of the asking price most of the time, and I never lowered the price twice. I also didn’t take less money than the sale was worth. What I mean is, if someone had tried to talk me down on a 25 cent item, I would have waved them away: at that point, I’d rather donate the item than get into a detailed discussion over ten or fifteen cents.

Three cash boxes

We actually had three groups of people benefiting from sales: 1) the adults in the household; 2) my son; and 3) our two girls. In order to keep things non-confusing, we had three cash boxes, and we put the money in those as it came in. I wouldn’t have wanted to try reconstructing sales after the fact or otherwise figuring out how to divide the money.

All in all, the sale did its job. It did move a number of things we wanted to get rid of and got them to useful new lives in other people’s homes, which is great. It didn’t get rid of a lot of the items we had on offer, but we now have tried and failed to sell those items, and we can give them away knowing that we’re not tossing out easy money. (Besides, giving things away to good people or organizations has its own rewards.) To put it another way, having the garage sale gave us the green light to get rid of everything that was left at the end, and it’s hard to put a high enough value on decluttering your life.

Photo by sea turtle

September 21, 2012

Inclusivity and Exclusivity in Fiction: Leah Bobet on Literature as a Conversation

This is the sixth interview and the eighth post in my series on inclusivity and exclusivity in fiction. You can find a full list of other posts so far at the end of this piece.

In today’s post, we get to finish the discussion we started some time back with writer Leah Bobet.

LUC: In our first round of questions, you mentioned Poppy Z. Brite’s book Drawing Blood, saying “Besides all the vampire sex and killing, what I took from that was that gay people are just people with relationships and problems and to do lists and lives to run and stories,” and you went on to describe how that has affected how you see and understand many kinds of people in the world. Are you consciously trying to create “aha” moments like this for your own readers? Are your goals for inclusivity in your writing explicit and specific?

LUC: In our first round of questions, you mentioned Poppy Z. Brite’s book Drawing Blood, saying “Besides all the vampire sex and killing, what I took from that was that gay people are just people with relationships and problems and to do lists and lives to run and stories,” and you went on to describe how that has affected how you see and understand many kinds of people in the world. Are you consciously trying to create “aha” moments like this for your own readers? Are your goals for inclusivity in your writing explicit and specific?

LEAH: I’m not, no – and I’m not sure if one deliberately can create that moment. Every reader’s set of experiences and stories and, well, their brains are different. The “aha” moment is when the story being told combines with the rest of your life and data and experiences in a way that tips over a realization you’ve been on the verge of making. It’s so very rooted in the reader that I’m not sure crafting it is possible.

What you can do, I think, is present the world as you see it, or the questions you’re sitting up nights asking yourself. And people will either agree or disagree with what you show them, or go off asking all new questions that you never could have predicted.

As for goals for inclusivity, mostly the goal for me is to have it — which could be read as extremely explicit and specific, or not at all! But to be clearer: I don’t write to a moral point, or to proselytize in any way. It didn’t take more than five minutes’ experience as an editor to learn that there’s a difference between a story and a piece written To Make A Point ™, and that the latter is very difficult to make into an interesting or engaging read.

What I do try to write is the kinds of stories I want to read as a reader, and those are stories that challenge me; stories that can both sweep up my heart and make me really and truly think; stories that examine social values without trying to sell them to the reader. The stories I write are populated by all kinds of people because I want to read stories like that, and because that’s the world on my block, in my neighbourhood, in my city.

LUC: When a writer tackles a story that includes someone from a group they’re not a part of, what tests or steps or touchstones should be used, in your opinion, to do the job right?

LEAH: Youch – I am not at all qualified in any fashion to say how one can do the job right. You can do all sorts of recommended things and still drop the ball on this sort of thing, or do none of them and do a really productive job. It’s all situational, and it depends, also, on what job you’re trying to do.

I think there are two main factors to look at when you’re writing characters from a marginalized group, however you choose to tackle them. The first: What’s the existing social and literary conversation around how that group is portrayed? What are the in-person stereotypes about them, and what are the fiction stereotypes? Because even if you’re not aware of or writing out of that stereotype, literature’s a conversation, and your comment (to stretch that metaphor!) will be taken as part of the larger conversation. If it’s just reinforcing that, or not acknowledging in certain ways that there is a conversation going on, then it’s very easy to do harm.

I’ve tripped on that one myself: Thinking I knew the ground around how a minority is treated in fiction, and not in fact knowing it at all. That particular piece of work hurt readers, and I can tell you unambiguously that causing harm with your work – using the trust a reader grants you carelessly, or using it ill – is a horrible feeling. It’s not one I personally care to repeat.

The second factor? Remember that your characters are people.

This sounds small, but it’s actually pretty big. Remembering someone’s a person can mean remembering that someone from group X will have things that make them laugh and cry and roll their eyes just like someone from group Y will. It can mean that they’ll be more or less attached to the culture and religion and society they grew up in, or in different ways, depending on their personality and experiences. It can mean looking at their reactions as not something opaque and Other and strange, but as reactions to people around them being kind or cruel, or what has been expected of them, or what success and failure were laid out to mean when they were young. It also means that they have a personality, and that there isn’t a standard, textbook way for people of group X to react to those things: anyone who’s ever had an argument with their siblings can pretty much back that one up.

In short, you are writing a human being. Treat them as such: as someone complete.

This means, a lot of the time, learning not just to watch, and to see, but to empathize. Which doesn’t mean to feel bad for someone; it means to, to the best of your ability, shift your own perspective. What might your street look like to someone with mobility issues? What would a character who grew up on a farm notice when they walk into a city park, and what would one who grew up in Manhattan notice?

This isn’t just a tool for writing characters different than you; it’s a tool for writing any characters well. And it’s a tool that ends up bleeding, like all the best ones do, into your life: Because real people are complete and complex humans too, and once you’ve gotten into practice in taking other perspectives and not assuming your own is the only perspective? You’re seeing people. And that will reflect in your interactions; in how you treat your neighbours in the small things; and in how they notice, and treat you in return.

LUC: We’ve talked a little about Drawing Blood. Are there other books or stories that, for you, stand out in this regard? If so, what did they do right?

LEAH: Actually, this might appear to come a bit out of left field? But: Anything by Sean Stewart. Specifically Galveston, or Nobody’s Son.

LEAH: Actually, this might appear to come a bit out of left field? But: Anything by Sean Stewart. Specifically Galveston, or Nobody’s Son.

If you subscribe to the theory that every author has a couple themes or problems they keep returning to, picking at around the edges, then one of Stewart’s is about realizing that you’re actually a complete asshole, and then what you do after that realization hits. This is useful to everyone, I think, because I have not yet met a person of any identity makeup who hasn’t been an asshole to somebody. In activism or just in daily living, the skill of what you do after you’ve been hurtful to someone else is a very useful one to practice, no matter who you are. They’re flawed books about flawed people, and I’m not put off by either the books or the protagonists being flawed, because they’re also clear-eyed and kind.

So, what did those books do right for me, as a reader? Aside from being quite well-made in a lot of ways – Stewart has a real skill with subtlety and nuance, especially when it comes to his characterization – the thing that affected me about them was that they’re so non-judgmental. They let you in close to people who are wounded and recognize those wounds as valid and real, and then show how the behaviour that woundedness causes hurts other people, and how that pain is valid, too. And I think that’s the key: That pain is valid too, not instead. There’s an immense compassion in recognizing that we’re all capable of simultaneously being the people dealing the hurt and receiving it, or acting out of old hurt while acting well or badly. Rendering that into fiction is a very tricky thing – almost as tricky as practising that kind of compassion in life. And it’s just as worthwhile, I think.

Leah Bobet is the author of Above, a young adult urban fantasy novel (Arthur A. Levine/Scholastic, 2012), and an urbanist, linguist, bookseller, and activist. She is the editor and publisher of Ideomancer Speculative Fiction, a resident editor at the Online Writing Workshop for Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror, and a contributor to speculative web serial Shadow Unit.

She is also the author of a wide range of short fiction, which has been reprinted in several Year’s Best anthologies. Her poetry has been nominated for the Rhysling and Pushcart Prizes, and she is the recipient of the 2003 Lydia Langstaff Memorial Prize. Between all that she knits, collects fabulous hats, and contributes in the fields of food security and urban agriculture. Anything else she’s not plausibly denying can be found at leahbobet.com.

7/27 – interview with Leah Bobet

7/29 - Where Are the Female Villains?

8/3 – interview with Vylar Kaftan

8/9 - Concerns and Obstacles (multiple mini-interviews)

8/10 – James Beamon on Elf-Bashing

8/17 – Steve Bein on Alterity

8/24 – Anaea Lay on “An Element of Excitement”

September 20, 2012

How to Turn Complex Choices into Hard Numbers

I was recently struck by writer and entrepreneur Chris Guillebeau‘s recommendation for a way to choose between a number of possible business opportunities, and I realized immediately that it was applicable not just to business decisions, but to any choice that involves a lot of competing possibilities with different pros and cons. It’s not a new idea, but it’s a useful one if you want to take a lot of possibilities and end up with a single score for each one so you can decide which is best.

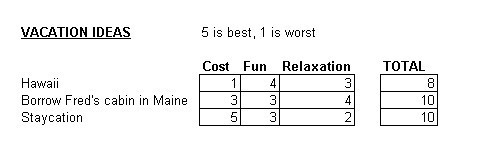

In a nutshell, what you can do is figure out what factors are important to you and rate each idea or possibility on a scale of 1-5 for each of those factors. You can use paper, a word processor, a spreadsheet, or another medium. What you get in the end is a grid, kind of like this:

The 5-point scale

Why a 5-point scale? Because it’s detailed enough to be able to distinguish between levels like “terrible,” “bad,” “OK,” “good,” and “great” while not so detailed that it’s difficult to decide what value to assign. The process isn’t supposed to be surgically precise: it’s just meant to show us which way the wind is blowing. Our quick, subjective impressions of each item will generally be good enough information to provide the answers we’re looking for.

Keep in mind that 5 always means “best,” not necessarily “highest.” For instance, Hawaii has a 1 for “cost” not because the cost is low, but on the contrary because the cost is high and therefore merits the worst rating.

While I think a 5-point scale is especially handy, you can use any scale you want (say, 1-3 or 0-10, etc.). Just be sure to use the same scale for every factor.

Instant insight

You can see right away how this approach is handy. For instance, Hawaii might sound great, but when you factor in the very high cost and the lower amount of relaxation you experience because of airports, reservations, and all the rest, it doesn’t stack up as well (using this method) as the other two options.

Weighty questions

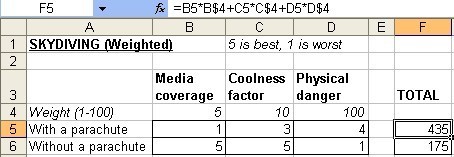

With that said, there’s a major problem with the system as Guillebeau and many other people use it, which is that it treats all considerations as equally important. In many cases, that works out fine; as I say, we’re just trying to get a general direction. In other cases, though, it can be … well, less than ideal. Consider the following example:

Using this approach, it’s easy to see that it’s better to dive without a parachute than with one–except that … you know … it isn’t.

So how do we fix this problem? By using weightings!

What are weightings? They’re just a way of adding up or averaging information proportionate to other informance, in this case to information about how important each item is. By introducing weightings, we can let our grid reflect our priorities. Consider this new version of the skydiving grid:

Our totals have changed completely, and they shouldn’t be compared to totals from any other grid, but they tell a clear story: even for this obviously danger-loving individual, skydiving with a parachute is a much better choice than skydiving without.

Of course, using weightings is more complicated than not using weightings, especially in terms of calculations, because you have to multiply each rating by its weighting before you add things up. If you don’t want to get technical, I’d like to invite you to skip down to the picture of the kitten now, and I’ll mention that I can probably upload a template that won’t require you to do any of the technical work if enough people want it.

If you don’t mind getting technical and are following along in Excel, here’s how I set up the spreadsheet so that the total would use the weighting values I specified:

The little $ signs, in case you haven’t used them in Excel before, mean “use the row (or column) I specify even if I copy this formula somewhere else.” By referring to B$4, C$4, and D$4 instead of B4, C4, and D4, we can copy the formula from F5 into all of the rows below, even if we add a hundred options, without having to change the formula.

OK, it’s safe to read on! No more technical stuff!

photo by Merlijn Hoek

Just useful; not miraculous

Weighting isn’t perfect either, of course. It’s hard to put hard numbers on the relative importance of things like “environmental friendliness” and “good for the kids,” say, and if we just put the highest importance on everything, then we might as well not be using weightings at all. Also, if we have two different but related factors (like “general aesthetics” and “goes with the furniture”), then both of those add together to give them a weight that’s probably higher than intended–although if we’re using weightings, this can be fixed by cutting both weights roughly in half because the two are in a sense working together. This same problem comes up if we don’t use weightings, but in that situation, there’s no good way to fix it, so that’s another point in favor of using weightings instead of unweighted ratings.

I don’t want to lose sight of the benefit here: the amazing thing is that you can take any number of choices–just a handful or hundreds–and evaluate them all at the same time. There are other ways to make these kinds of choices, like filtering and sequencing (see “How Fewer Choices Make for Better Decisions“), but using weighted ratings makes it possible to evaluate them all at once and to tweak the decision-making process afterward to see how that changes things. (Because you can always decide to add or change your ratings or alter their weights, and in a spreadsheet or similar solution, those changes will immediately show new scores.)

Using your results

If you’re using a spreadsheet, you can sort by totals when you’re done (in Excel, highlight all of your data, including the choice names and the totals, then choose Data > Sort) so that your choices are then listed in the order from best to worst, according to your spreadsheet.

You don’t have to then make the choice at the top just because it got the highest score: again, this process is just a way to put things in perspective. However, that perspective can be invaluable for figuring out what to actually do next.

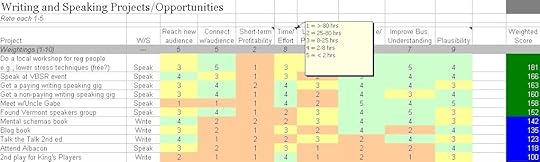

My example

I put together a spreadsheet for myself of a few of the many, many speaking and writing projects and possibilities I’ve started or considered, and set it up using weighted ratings, as I’ve described above. Having a technical background and being very interested in squeezing every last drop of meaning out of my information, I made some further enhancements, which you can see here. Note the little red corners: those mean that I can hover over the factor with my mouse to see details of how I should rate, so that I can assign ratings consistently. I’ve also used conditional formatting to highlight better and worse information with different colors. (You can click on the image to see it at full size.)

If you’d like a copy of my template for the grid above, please comment here. I’ll put something fairly user-friendly together and post it if there’s a need.

September 17, 2012

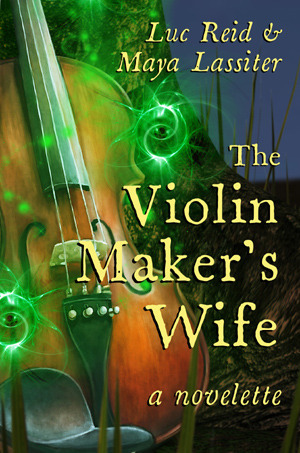

Collaboration Leads to 1800′s Witchery: The Violin Maker’s Wife

I met fellow writer Maya Lassiter (who writes an eclectic and highly entertaining blog about her yurt-living, kid-and-goat-raising, writing life) back in 2001, when Orson Scott Card ran his first annual writing week, called Uncle Orson’s Literary Boot Camp. The workshop was open to 20 of us, who auditioned with writing samples, and it was completely transformational to my writing. Scott Card was the first one to get me to understand that you didn’t have to wait for ideas, that you could go out and find them whenever you needed them. He was the one who explained that most of us write about a million words of garbage (literally) before we really start getting good. He was the one who explained to me the principles of writing clearly rather than prettily.

It’s not a great surprise to me that many students of that Literary Boot Camp have gone on to substantial success. Doug Cohen became a successful fiction writer and the editor of a major fantasy magazine. James Maxey authored multiple successful novels, including the Bitterwood and Dragon Age series. Jud Roberts‘ deeply-researched and adventure-filled Strongbow Saga has garnered eager fans for its first three books, with a fourth on the way. Ty Franck’s collaboration with Daniel Abraham (as James Corey), Leviathan Wakes, became a bestseller. I could go on.

In any case, I later founded a group called Codex, which many Boot Camp alums joined, including Maya, and on Codex we like to have fiction contests. When we held a collaboration contest, Maya and I got together and came up with a story about violin making and badly-understood magic, a novelette that was eventually titled “The Violin Maker’s Wife.” It won that contest.

A couple of months ago, Maya and I decided to put the story out where it could be read and published it for the Amazon Kindle. Note that Amazon Prime members can read it free by using their free monthly Kindle rental.

Maya worked with her regular cover artist, Ida Larsen to devise a cover, and recently we finished the formatting and took it live. Here’s the description:

“The Violin Maker’s Wife” is a historical fantasy novelette, set in 1870s Missouri, and is about forty pages long.

“The Violin Maker’s Wife” is a historical fantasy novelette, set in 1870s Missouri, and is about forty pages long.

Nora Warren always knew there was something uncanny about her husband Tom’s work. What she didn’t know what that his enchanted violins could be deadly. Tom’s friend has one of the exquisite instruments, as does Tom himself. So does Garrett, Nora’s only son.

But Tom has looked too deeply into his own magic, and Garrett is in danger. Now Nora must find the answers Tom can’t give her, even if it means searching for spells hidden in his workshop, questioning a secret society of musicians, and following dangerous lights out into the wilderness. Tom has looked where he shouldn’t, but to save Garrett it’s Nora who must find who–or what–has looked back.

September 13, 2012

The Case for Not Eating Breakfast

Disclaimer: I’m not a doctor or a nutritionist or a health professional of any kind. Don’t take anything in this post as official advice: I’m just documenting an experiment I’ve been trying.

Is breakfast really the most important meal of the day? For years I assumed it was. When I was a kid, I vividly remember a public service announcement starring Bill Cosby in which he illustrated how, if you don’t start the day with a good breakfast, you “run out of gas.” (Sadly, YouTube has failed me in finding that clip. Maybe my memory has glitched and it wasn’t Bill Cosby. Someone else on the Internet thinks it was O.J. Simpson.) Also, it just seems like common sense: food is fuel, and if you don’t fuel up at the start of the day, you won’t have any energy.

Except that I’ve been skipping breakfast most days for weeks now, and if anything I’m more energized–and freakishly, less hungry!–in the mornings. What gives?

Tempting ourselves because we’re not hungry?

About six weeks ago, I tweeted about an article called “The Breakfast Myth” in which J. Stanton makes some thought-provoking points about breakfast. One that particularly struck me is how much breakfast often resembles dessert or snacks: it features sugary, starchy, and fatty foods like sweet cereals, pastries, sweetened yogurt, pancakes or waffles or french toast with syrup, toast with butter, bagels, granola, or even sweetened “protein bars.” True, there’s always the traditional fat-and-protein breakfast of eggs and bacon or the like, but at least here in the U.S., the snack/dessert breakfast seems to predominate.

There are a lot of different conclusions we could try to make from this information, but Stanton’s struck a chord with me: the reason we’re eating these treat-like foods for breakfast could be that we’re not really hungry in the morning, and so especially tempting foods are the only thing that can get us interested in eating. Sure, we’re used to having a meal at that time, and out of habit (both mental and physical) we expect to munch on something soon after we get up, but are our bodies really clamoring for food?

I can’t speak for anyone else’s body, but it appears that my body isn’t. In the past six weeks, I decided I would only eat breakfast in the morning if I were actually hungry. As a result, I find I eat breakfast, on average, maybe twice a week. I seem to be more likely to be hungry in the morning if I’ve had an intense workout the night before or (interestingly) if I’ve had a lot of sugar the night before–something I try to avoid.

The history of breakfast

Ever wonder where that saying “Breakfast is the most important meal of the day” came from? Stanton answers that question (I was also able to find some evidence to support his conclusion), and the answer isn’t some nutritional authority or medical association. Did you ever read Franz Kafka’s short story “The Metamorphosis” (“Die Verwandlung“), in which a young man named Gregor Samsa wakes up one morning to discover he’s turned into a giant cockroach? It appears to come from that story. The earliest appearance of that statement appears to be this passage:

The washing up from breakfast lay on the table; there was so much of it because, for Gregor’s father, breakfast was the most important meal of the day and he would stretch it out for several hours as he sat reading a number of different newspapers.

Gregor’s father is not especially demonstrating good nutrition or productive habits. He’s not making a general statement about human physiology. He’s not even an actual person! So let’s throw that one away right along with “It takes 21 days to form a habit” (it doesn’t: see “How Long Does It Take to Form a Habit?“).

Stanton suggests that humans didn’t evolve to eat breakfast because early humans wouldn’t have had anything lying around to eat when they woke up. That seems like a bit of a stretch to me: why not have a few berries or a root or some smoked antelope haunch sitting by, as long as you have a fire to keep the predators away? Whether I have an evolutionary explanation or not, though, I’ll go with my gut–literally. Generally speaking, it says it doesn’t want breakfast.

Other problems that didn’t come up

Some problems you might expect to see with leaving out breakfast haven’t materialized for me. As I mentioned, I have at least as much energy as when I ate breakfast, and possibly more. This may have to do with how we metabolize sugars (and starches, which break down into sugars): they can cause insulin spikes in our bodies that clean out all the sugars and can lead to a sugar crash, not to mention the mid-morning munchies (which I also haven’t had when skipping breakfast). I haven’t been eating more later in the day, either: so far, I have yet to find any ill effects at all. There have been studies, too, to try to determine whether people who miss breakfast make up the calories by eating more later in the day. As a rule, it turns out, they really don’t.

I should mention that by hungry I don’t necessarily mean I want something to eat–I mean that my body is actually asking me for nutrition. If some morning I start hankering after, say, toasted maple bread with marmalade, I just ask myself “Would you still want something to eat if it were some beans, or baked chicken breast?” Usually, the answer is no. Apparently, in those situations, my mouth just wants something entertaining to munch on. I generally don’t oblige it. Taste bud boredom is not the same thing as hunger.

But what if I like breakfast?

Of course, there’s no reason to give up on breakfast if it’s working out perfectly well in your life. If you’re happy with your nutrition and your morning routine, especially if breakfast gives you a little quality time with the family or something like that, then I say hey, bring on the English muffins.

On the other hand, maybe you’d like to lose some weight, or your mornings are very hectic and tied up in large part with making, eating, and cleaning up after breakfast. Alternatively, maybe you just want to see how you feel if you don’t eat breakfast. In that case, you might consider giving a no-breakfast-unless-you’re-actually-hungry approach a try.

Better breakfasts

Another alternative to consider is healthier breakfasts, especially ones that don’t have much in the way of sugars and starches and instead emphasize protein and fiber, perhaps with a modest amount of healthy fat. This rules out most of the traditional breakfasts and instead suggests things we’d be more likely to think of as dinners: meat, fish, poultry, other kinds of protein (like soy and seitan), some dairy, beans, and vegetables. Eggs are still in, and nuts work to some extent, although they have a lot more fat for the amount of protein they offer than some other protein sources and therefore are something that’s best eaten in moderation.

I started eating these kinds of “dinner” breakfasts when I tried Tim Ferriss’ “slow carb” approach to eating (which gave me some new nutritional tricks, but which overall I can’t really recommend), and I’ve certainly found I’ve been more satisfied by them and more energetic throughout the day than with sugar-and-starch-heavy breakfasts. Beans especially are great to have at multiple meals (though don’t eat the liquid they’re cook in, so as not to have to experience the traditional complications) because they offer vitamins, minerals, and plenty of protein and fiber to help keep hunger away for a good long while.

I have to admit, I rarely felt hungry in advance for a breakfast of, say, fish, kale, and lentils–but I almost always found once I started to dig in that I really enjoyed the food. On reflection, it doesn’t surprise me that I wasn’t hungry for them, since it appears I’m not especially hungry at all in the mornings; I had been used to the “treats for breakfast” mentality. Perhaps if I’d been raised in Japan, my stomach might think differently.

A Japanese breakfast

I’ve said already that I don’t have any credentials as a nutritionist or physician, and I’ll repeat that now just for emphasis. Who knows? Skipping breakfast may be the quickest route to some terrible disease. However, I’m betting the opposite, that listening to my body and not eating in the morning if I’m not hungry is going to be the most healthful approach I can take. For you, I wouldn’t even want to venture a guess, but here’s to whatever your healthiest breakfast turns out to be, whether that’s a traditional one, protein and vegetables, or nothing at all.

Top photo by lesleychoa

Japanese breakfast photo by herrolm

September 11, 2012

Wait, You’re Not a Real Writer at All!

The original version of this article first appeared in my column “Brain Hacks for Writers” over at the online publication Futurismic. I’m editing and republishing each of my BHfW columns here over time.

Writing professionally, or even just aspiring to write professionally, requires a weird combination of hubris and humility. You have to be willing to believe, at least for the 15 minutes it takes to put together and send out your submission, that the stuff you make up and write down is so fascinating that thousands or tens of thousands of people would pay good money to read it. The Hollywood Bowl has a seating capacity of about 18,000, but even a modestly successful midlist novelist or someone who sells a story to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction reaches more people than that. Who the hell do we think we are?

At the same time, we have to embrace humility if we’re not going to drive ourselves nuts. Actors and salespeople are among the few who compete with writers in the “getting rejected” department–and even those professions don’t spend two years on a project, send it out, wait eighteen months, and receive in return a form letter saying “No thank you; good luck elsewhere.”

Impostor syndrome

So is it any wonder that writers are often susceptible to Impostor Syndrome? If you’re not familiar with Impostor Syndrome, you might be interested in the article “Impostor Syndrome” on this site, but short version is that it’s when you see your successes and you think they must be due to someone making a mistake. Any time you sell a story, get a bite from an agent, or receive a positive review, it seems like a fluke. Obviously these people don’t understand that I’m really a big faker, you might think, or if I wrote something good, it was just blind luck and will never happen again.

Many many writers I know struggle with impostor syndrome. From a certain perspective, it makes sense: if you spend years and years looking up to people who are getting regularly published in certain magazines or whose novels are making it into the hands of thousands of satisfied readers, and if during this time you get a constant barrage of polite but generally impersonal messages that say “No, this thing that you poured your heart and every ounce of skill you have into really isn’t any good,” then you’d have a pretty inflated view of yourself to not ask yourself if the sale you finally get isn’t some kind of anomaly. (No disrespect intended to those who, like me, lean more to the hubris side than the humility one.) Maybe the editor who bought your story was drunk when she read it. Maybe your new agent is confusing you with another writer who’s actually good.

Misdirected expectations

It can get even worse when you have a little success: maybe you sell a story or get an honorable mention in a major contest. What happens if the next story you send out fails miserably? It just reinforces the idea that the first success was a fluke–even though any decent statistician with access to writers’ track records would predict a few failures with a high degree of confidence, even for writers who overall became very successful.

It doesn’t help that we writers are not particularly good judges of our own work. (See “Your Opinion and Twenty-Five Cents: Judging Your Own Writing”). We may think a particular piece we’ve done is the best thing ever written, or may think it’s utter trash, and in either case we can be right on the nose, tragically wrong, or even both.

Thinking your way out

So how do you stop feeling like a faker? Well, there’s thought and there’s action.

In the thought department, we’re better off when we avoid telling ourselves things that are either false or questionable and instead stick to things we know are true. For instance, instead of thinking “I know this story is going to be rejected,” we can substitute the thought “This story might sell or it might not. If it doesn’t, I’ll send it somewhere else.” That process, called “cognitive restructuring” (or my preferred term, “idea repair”), may seem elementary, but it’s surprisingly effective, as research and clinical results have shown. If you’re interested in idea repair, which is useful for far more than just addressing Impostor Syndrome, you can find articles, books, and other resources on the topic here.

Where does confidence come from?

On the action side of things, one of the most productive things to do is more. Write more, send more out, and get more used to the rejections–and the acceptances. I was at my son’s high school yesterday for a parent presentation, and I was powerfully impressed to see what complete confidence and self-possession every one of his teachers showed when presenting to groups of parents. How can they be so confident? I asked myself.

The answer to where the confidence came from was quickly obvious to me: these are teachers who enjoy their jobs, and they stand up and talk like this for most of every workday. They have get in more public speaking in the typical week than many people will do in their lifetimes. Effective practice makes you better and better at what you’re doing, and it also quells concerns about whether you have any right to do it. I’ve written about 15,000 words of fiction in the past week. I know from critique responses (we sometimes get very rapid turnaround on critique in my writer’s group) that at least some of those words worked well for a good sampling of readers, but I have no way of knowing if the stories I’ve put together will sell or just become more rejection magnets. However, having written all that, and especially doing that and then sending the work out, I know that I’m a writer. Whether or not editors buy what I write is up to them and out of my direct control. All I can do is keep plugging away, always working on something new, concerning myself not with whether people accept what I’ve written but with how well I’m doing the job of churning out words worth reading.

The thing is, regardless of how successful your writing is now or ever, if you bust your hump putting out new works, and if you push the envelope to try to make yourself better at what you do, then you’re a writer–and you might as well be proud of it.

Photo by V’ron

September 6, 2012

What Our Garage Sale Taught Me About Decluttering My Mind

This past weekend, my family had our long-delayed garage sale. It’s been a two and a half years since I went through practically everything I owned and sorted it all into “keep” and “don’t keep”: the trick in the time since has been finding and setting aside enough time to organize, price, advertise, set out, and sell those items. In that couple of years, too, I’ve found that there are a number of additional objects I had that I could do without, and so along with everything else there needed to be another round of decluttering.

However, we did it all, and we survived. While I hope to not have to do another sale for a number of years, I feel like I’ve learned some useful lessons about running one successfully, and I’ll be putting that information in a separate post. This post, however, is about the emotional side of garage sales, because for many of us, getting rid of our old stuff is even a bigger emotional task than it is a physical and organizational one.

In the course of this sale, I’ve had to face a few truths about myself, my stuff, and my relationships, and it all continues to be challenging and sometimes even painful. Here’s what I think I’ve learned:

1. I’m not going to get what I paid for it: that money is gone

It’s nice to imagine when I buy something useful and well-made that I’m not really saying goodbye to my money: I’m just letting it go away for a little while. Eventually, when I no longer need the thing, I can just sell it and recoup much of my expense, right?

You probably aren’t falling for that and know as well as I do that the minute we take off the plastic wrap, whatever it is we bought no longer equals money: all it’s worth is its use to us plus sometimes a greatly-reduced resale value. Yet many of us find ourselves saying (or thinking) “But I paid ___ for that!” It’s hard to let go of the idea that things are worth what we paid for them, but at least in monetary terms, they hardly ever are. Maybe if you’ve recently bought a used Kindle Fire or something, you can get away with recouping what you paid for it, but that kind of thing is the exception, not the rule.

The hardest things for me to get used to losing value on, surprisingly, weren’t even mine: they were my son’s old toys. I would look at something and think “I remember when he was absolutely dying to own that,” and how we (or a relative at a birthday, say) had paid $50 or whatever it was for the item that was now sitting in our driveway on a sheet with a little sticker on it saying “$3.” It’s a hard lesson to learn, this evaporation of value, but it’s worth knowing–especially if it helps guide us into buying less stuff we don’t really need or won’t be able to use well.

2. The money I make won’t justify the time and effort, and that’s OK

One of the things I’ve been avoiding energetically is analyzing what my income per hour has been on this garage sale project. I’m not really making money in a meaningful way from doing this. What I’ve reminded myself, over and over (and it has helped), is that my payoff is in organization, space, peace of mind, and closure. All those objects in my life that have been hanging question marks (What do I do with this? Is it worth anything? How do I get rid of it? Do I really need it after all?) are being resolved into completed episodes of my life. Even if we hadn’t made a cent, all of the work was still necessary in order to get our lives back in order.

3. Bringing out old things brings out old thoughts

It was hard for me, during the sale, to relive some of my parenting from years gone by. I certainly don’t consider myself a world-class parent now, and currently I’m much, much better at parenting than I was years ago. Once again my son’s old toys gave me the most trouble: I remembered times when I’d been a just plain crummy dad. He used to have trouble sleeping starting when he was around 3, and I’d get angry when an hour after his bedtime he’d wander out into the living room. What I really wish I could do is go back in time and force some sense into my then-self, help myself realize that a kid who has trouble falling asleep probably needs some additional attention, affection, or comfort, and that a little patience would probably see the problem through much more handily and with much better impact for my kid than anger would. Other people might have to face reminding themselves of people they loved who had died, or relationships that went sour, or projects that disappointed. It’s hard stuff, sometimes, but it’s certainly a good thing to work through those old pains when we can and feel we’ve made our peace with them.

4. Giving things to people who can use them is kinda beautiful

One of my biggest challenges is my books: I have hundreds of books I no longer need that must have cost me at a thousand or two thousand dollars or more over the years, and I have been really attached to the idea of getting some money for them. When I asked about selling or giving away used books on Facebook, though, a number of friends came back with a series of terrific ideas (which I’ll detail in a separate post): schools in my area that could use them, hospitals, homeless shelters, bookmobiles … I realize that far better than making a little bit of money from my unneeded things, I can actually get them to people who want or need them. The eight bags of clothes in the back of my car that are on their way to Goodwill or the boxes and boxes of books I can donate so that suddenly there will be all these great new things to read just where people need them … that’s almost magical, you know? I like the idea of charity, but don’t get to do nearly as much of it as I’d like. Here, suddenly, is a beautiful opportunity to give from a position of real (but non-monetary) wealth. What a huge improvement over boxes of books taking up space and never getting read!

I know that for many of you out there, garage sales aren’t this grueling. This is the first one I’ve had in years, and future sales probably won’t involve all the same memories and clutter. My point, though, isn’t that garage sales are always hard–it’s that decluttering our homes and lives goes with the difficult process of decluttering parts of our minds, and that if we’re having trouble with one of those things, it may help to turn our attention to the other.

It just takes a bit of courage. And time. And maybe a garage.

Quinn Reid's Blog

- Quinn Reid's profile

- 6 followers