Quinn Reid's Blog, page 14

June 1, 2012

Research Suggests Self-Awareness Helps Maintain Willpower

I’ve extolled the virtues of mindfulness here on LucReid.com in a number of articles, such as “A Very Clear Example of the Power of Awareness” and “Mindfulness and Deer Flies.” A 2011 article by Hugo Alberts, Carolien Martijn, and Nanne deVries in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (“Fighting self-control failure: Overcoming ego depletion by increasing self-awareness“) offers some insight on why and how mindfulness–specifically self-awareness (which we might also call “mindfulness of self”)–may aid willpower.

You may well have heard the ideas of Dr. Roy Baumeister and others, who describe willpower as being a resource that can be used up. Although this idea is popular, I’m inclined to think it’s off the mark: some of the concerns are described in my article “The Debate Over Whether Willpower Tires Our Brains.” Alberts, et al’s work seems to support the idea that willpower isn’t used up so much as misplaced.

In their study, the authors had participants work at a task that required willpower: holding an exercise handgrip closed for as long as they could. They would test a subject with this task once, then have them perform a slightly tedious task or else a highly annoying task that according to previous research should cause them to have reduced willpower on their next attempt. However, before that second attempt, they had one group unscramble sentences with the word “I” in them and another group unscramble sentences about other people, reasoning that the people who unscrambled the “I” sentences would think more about themselves–i.e., be more self-aware.

What happened? The group that unscrambled sentences about other people, as expected, had reduced willpower on their second attempt in holding the handgrips–the normal result. The group with the “I” sentences, however, did just as well as they had the first time: their willpower wasn’t diminished.

How cool is that? Paying attention to yourself, it appears, can help you maintain willpower. This is good news in situations, like dieting, where exercising willpower repeatedly is essential.

Thanks to Dr. Art Markman, whose post about this study brought it to my attention, and Vince Favilla for tweeting about that post.

Photo by _ado

May 29, 2012

Does Simply Believing That You Can Improve Help You Improve?

An intriguing post from Stanford psychology professor Carol Dweck offers the idea that simpler believing you can learn to do better can give you an advantage in performance, over time.

Dr. Dweck describes two ways to look at skills and abilities: the “growth mindset” and the “fixed mindset.” The growth mindset is a belief that practice and experience can improve skill. The fixed mindset is a belief that you’ve either got it or you don’t.

Based on other research, the growth mindset appears to be a lot more accurate: see past articles on LucReid.com such as “Do you have enough talent to become great at it?,” “Why I’m Proud to Have Been an Unoriginal, Talentless Hack,” and “Practice versus Deliberate Practice.” However, this isn’t Dr. Dweck’s point. Instead, she describes how the very belief in the possibility of improving tends to boost ability over time:

The fixed mindset, in which you have only a certain amount of a valued talent or ability, leads people to want to look good at all times. You need to prove that you are talented and not do anything to contradict that impression, so people in a fixed mindset try to highlight their proficiencies and hide their deficiencies (see, e.g., Rhodewalt, 1994) … In contrast, the growth mindset, in which you can develop your ability, leads people to want to do just that. It leads them to put a premium on learning.

Some interesting additional details: in studies, Dr. Dweck and colleagues found that people might have a growth mindset in one area but a fixed mindset in another. For instance, you might believe you can get better at drawing, but not at socializing, or you might think you can improve at baseball but not at math.

Mindsets are fairly durable, but as Dr. Dweck points out, “they are beliefs, and beliefs can be changed.” The lesson for all of us seems to be that having faith in our own ability to improve will serve us well regardless of what area of life we’re talking about. To cultivate this belief, I can recommend a couple of books: Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers and Geoff Colvin’s Talent is Overrated.

Photo by Express Monorail. Thanks to Vince Favilla for tweeting Dr. Dweck’s article.

May 25, 2012

Inspiration: Essential Magic or a Load of Hooey?

Ah, Sweet Panic!

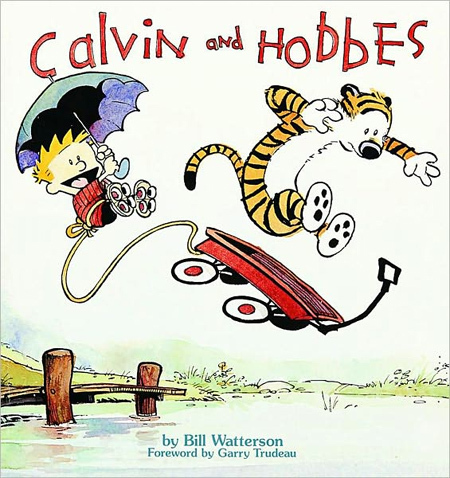

Cartoonist Bill Watterson cranked out one brilliant Calvin and Hobbes comic strip after another for about ten years. Even if (bizarrely) you aren’t a fan of Calvin and Hobbes, it’s clear Watterson knew how to create art that spoke to a lot of people in a clever, funny, and meaningful way. Here’s a conversation his two main characters had about inspiration.

HOBBES: Do you have an idea for your project yet?

CALVIN: No, I’m waiting for inspiration. You can’t just turn on creativity like a faucet. You have to be in the right mood.

HOBBES: What mood is that?

CALVIN: Last-minute panic.

It’s interesting how effective last-minute panic really is. I don’t know if you’ll have as many examples in your life as I do in mine, but can you recall an incident or two in which you delayed doing something because you didn’t feel like you had any good ideas, then were forced to do come up with an approach at the last minute that came out great?

I’m not suggesting this is a formula for success, because a lot of last-minute efforts are terrible. What’s interesting about this phenomenon, though, is how often just sitting down and doing the thing can force inspiration to appear out of nowhere.

Angels and Bounty Hunters

The “inspiration on demand” idea seems directly in conflict with the “angel whispering in my ear” idea of inspiration: in the latter, a really good idea comes out of the blue and is out of the artist’s control. I actually do believe in this kind of inspiration. Our brains are chugging along all the time doing all kinds of stuff, and if on some level we’re looking for ideas, some chance collision of elements will sometimes create something spectacular. When something like this comes along, there’s nothing wrong with seizing it–although treating it as holy writ can be a problem, since there’s no guarantee the idea is already in its ideal form (see my Futurismic columns “There’s Always Another Way to Write It” and the “What Else?” portion of “Writing Differently: Picking Up the Scary Tools” ).

The problem I’m concerned about here, then, isn’t using inspiration that appears out of the blue, but rather waiting for that kind of inspiration, like Calvin. Good ideas can arise on their own, but they can also be dragged out kicking and screaming. Here are a few ways to do that, with an emphasis on ideas for writers (though many of these approaches can work for any kind of artist).

Juxtaposition

Take a story line, emotional state, event, character, or situation that interests you and throw it in with something else that isn’t usually associated. Think of Blade Runner (androids and private eyes) or Watership Down (rabbits and prescience) orEnder’s Game (children and space).

Reversal

Take a cliched story setup and reverse it. Make the private eye deeply in touch with his emotions; make the bunny deadly (although admittedly, that’s been done by Mssrs. Python); write a coming-of-age story about a 72-year-old. Make those cliches wail and gnash their teeth.

One of the most engaging ways to create gripping writing is to find a way to make things worse–ideally, the worst they could possibly get (prior to you then coming up with something even worse that will happen later). Suzanne Collins starts her gripping novel The Hunger Games with a character worrying about being chosen for a deadly contest–until that worry is completely erased when the character’s relatively helpless younger sister is chosen instead.

What happened to you

One of the great things about real life is that it doesn’t get upset when you steal ideas from it. J.K. Rowling created some of her most engaging characters based on people she knew growing up. Bringing your own experience into a story creates an emotional immediacy that’s otherwise often hard to come by.

Yadda yadda yadda

At this point in this piece I find I’m coming closer to giving advice about writing than talking about motivation for writing, which means I’m getting off-topic. Let me steer back on to point out that one of the things that creates excitement about writing a story is having wonderful ideas about who and what will come up in that story as it proceeds. When the ideas (about characters, plot, setting, incidents, problems, etc.) are strong enough, we can’t wait to see what happens in our own stories, even when we already more or less know how things will come out. When we instead depend solely on ideas that volunteer themselves, really compelling ideas may be too scarce to keep us fired up–but when we generate the ideas on demand, stopping to create something amazing whenever something amazing isn’t already there for us, then we create our own propulsion, carrying us forward further and faster into our own work.

This piece is adapted from my Futurismic column “Brain Hacks for Writers”

May 23, 2012

The Most Troubled Plurals in the English Language

It’s funny, but I haven’t been able to find a post on the Web about the most difficult pluralizations in English. Maybe I’m just not looking hard enough. Regardless, I decided it was easier to put together my own than to keep looking; here it is.

It’s funny, but I haven’t been able to find a post on the Web about the most difficult pluralizations in English. Maybe I’m just not looking hard enough. Regardless, I decided it was easier to put together my own than to keep looking; here it is.

The thing about plurals is that you start running into a lot of trouble about “common usage” versus “correct usage” and whatnot. I’ll say right here that I think that language is defined by usage. At the same time, I hold the completely contradictory belief that sometimes lots and lots of people are making the same mistake. It’s not a tenable position, but I’m holding it anyway. It seems to work for me.

Even if you’re not in love with the English language, as I and many of my writer friends, are, I can think of three reasons to care about getting plurals right. The first is pretty minor, and it’s clarity: expressing yourself in a way that’s precise and unlikely to lead to confusion.

The second is attention to detail, because people who feel very attached to “proper” language may tend to judge your speaking, writing, and/or general intelligence ungenerously if they don’t like your plurals.

The third is steering clear of something that’s for some people is a pet peeve, as a compassionate and charitable act. Good plurals are good karma (or at least less likely to get you dragged into tedious conversations about “octopi” and “octopodes”)!

With those initial notes, let’s dive right into the plurals and plural-related expressions. Where possible, I’ve listed each by the singular followed by a colon and then the plural. Here we go!

dwarf: dwarfs or dwarves

“Dwarfs” used to be preferred, but J.R.R. Tolkien, author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings used “dwarves,” and that has since become the most popular plural. You’re probably safer with Tolkien’s version, because who can gainsay Tolkien on the topic of dwarves? Still, if you like the retro feel, “dwarfs” is perfectly acceptable.

roof: roofs

Australians and people from long ago have been known to use “rooves,” but most contemporary English-speakers (at least in the northern hemisphere) will look at you funny or shout you down if you use that, so “roofs” is the best way to go unless you like to rile people, in which case feel free to drive some people through their rooves.

Kennedy: Kennedys

It’s the same for other names and places. You’d think it might be “Kennedies,” but proper nouns aren’t subjected to the -Y to- IES rule, I guess because it’s considered rude to muck with someone’s name. It definitely isn’t “Kennedy’s”: see the next section.

Never, ever pluralize with an apostrophe–except when it’s OK

So you’ve probably seen signs on stores saying “Sale on shoe’s!” and “Sorry, we’re out of apple fritter’s.” These are simply and pitiably wrong. People have a tendency to throw in an apostrophe when they’re not used to pluralizing something, for instance saying “The only government that would do more of this would be one led entirely by Barack Obama’s.” This is wrong, wrong, wrong.

However, you can get away with pluralizing numbers and letters with an apostrophe (at least using some style manuals). For instance, you can write “I got all A’s and B’s” or “My scores have all been 3′s.” You can also write “As and Bs” and “3s”, though. I think the reason the apostrophe was allowed there is that the letters, at least, look like they’re trying to form words when you leave it out. Anyway, it’s your choice.

octopus: There is no good answer

The plural of “octopus” you’re most likely to get away with is “octopuses,” because it’s a standard English pluralization and is widely used.

However, “octopi” is also widely considered acceptable. Unfortunately, some people will insist it’s the only correct one (because in Latin words that end in “-US” are pluralized with an “-I” ending), while other people will insist it’s horribly wrong (because “octopus” comes from Greek, not Latin!), while yet other people will point out that even if it’s wrong, “octopi” has been in use for centuries, so it doesn’t matter whether it was invented for good reason or not: it’s part of the English language, and that’s that.

At a certain point people tried to correct “octopi” by substituting a more Greek-like plural, making it “octopodes.” This variant seems to be more popular in the United Kingdom and/or when talking about different species of octopus.

My recommendation? Stick to one octopus at a time and save yourself the heartache.

platypus: platypuses

“Platypus,” like “octopus,” is from the Greek, but there’s been a lot less arguing about this particular plural, and “platypuses” is a pretty safe bet.

nucleus: nuclei or nucleuses

syllabus: syllabi or syllabuses

focus: foci or focuses

These are regular old Latin plurals. Of course, most of us don’t speak Latin, so it helps to memorize them. Alternatively, the Anglicized “-es” forms are also acceptable (and sometimes, as with “focuses,” are sometimes preferred).

Worried about the pronunciation of “foci”? Don’t be. People pronounce it “FOE-kee,” “FOE-kai,” “FOE-see,” or “FOE-sai.” Just pick your favorite!

datum: data

medium: media

I’m afraid this is one I actually care about, because I’ve dealt with a lot of data in my time. One piece of information is a “datum,” while a bunch of pieces of information are “data.” So technically, saying “The data is wrong about this” is a little off. However, in common usage for at least a few decades, people have been using “data” as a collective noun (like “faculty”), because who cares about just one piece of information in an age that practically drowns us in information? Therefore most people will have no trouble with you saying “the data is wrong,” but a few of us will gnash our teeth, tear our hair, rend our garments, wail, etc.

“Medium” is in a similiar situation. Newspapers are one medium, while DVDs are another. Both are types of media. However, “media” is also sometimes used as a collective noun, like “data.”

criterion: criteria

This one actually has a right answer, and let common usage be hanged. One thing to take into account is a “criterion” (singular). If you have to take a lot of things into account, they’re “criteria” (plural). Please don’t say “This is the single most important criteria.”

Pretty please?

schema: schemas or schemata

Both “schemas” and “schemata” are used as plurals for “schema,” although in Schema Therapy, the plural is “schemas” only.

mother-in-law: mothers-in-law

sergeant major: sergeants major

court-martial: courts-martial

attorney general: attorneys general

Nouns made up of multiple words, like these examples, get the first word pluralized, partly because sometimes the words on the end are adjectives, and pluralizing an adjective just doesn’t make sense–except in Spanish or Russian or one of those other crazy languages that they speak in far-flung parts.

Proudfoot: Proudfeet

Another Tolkien reference. If it doesn’t amuse you, please disregard it and move on.

tornado: tornados or tornadoes

Either one is fine.

however

potato: potatoes

Enough said.

appendix: appendixes or appendices

“Appendixes” seems to be the best choice when we’re talking about the parts of the body, while “appendices” tends to be preferred when we’re talking about the information at the end of a book.

you: y’all: all y’all

I can’t think of many instances where a plural has a plural (unless you want to get into collective nouns, for instance “flocks of geese”), but this is one. In the American South, “you” is often pluralized “y’all,” although “you,” “you all,” and “you guys” are also used depending on the place and the person. Further, in all seriousness, if you’re talking to a large group, you can double-pluralize it and get “all y’all.” The difference seems to be a small group versus a large group. For instance: “Y’all want to go to the movies with me?” versus “All y’all at this movie theater [pronounce it thee-AY-tur] are too dang loud!”

After attending college in Florida for a couple of years, I came back to the North (also known as Them Yankees Up There) still using “y’all” because it was so useful. I gradually stopped, though, because I got tired of people looking at me funny over it. All y’all should stop doin’ that.

(By the way, I recognize that Florida doesn’t really count as part of the South, but there is a fair measure of y’alling going on down there.)

basis: bases

thesis: theses

parenthesis: parentheses

crisis: crises

All of these words ultimately come from Greek, in which (it would seem–I don’t speak Greek), “-IS” words are pluralized with “-ES.” More memorization fun for everyone! The nice thing about knowing the plurals about these is that you come across as extra-well-educated if you use them in grammatical crises.

species: species

Why? I have no idea. Sheep. Moose. Fish. Species.

cactus: cactuses or cacti

They’re both perfectly acceptable, and let no one tell you different. “Cactus” is a Latin word (although it comes from the Greek “kaktos”), so the Latin plural makes about as much sense as the English plural.

there’s trees in the forest (no, there aren’t!)

It’s common for people to use “there’s” when talking about multiple things, but this is technically wrong, because “there’s” is short for “there is” (don’t tell me it can also mean “there has,” because that’s not what we’re talking about here!).

Did I miss any important ones (not including academic and scientific terms)? Please add in the comments if you have ‘em.

A heartfelt thank-you to many writer friends who contributed ideas and facts for me to obfuscate and misconstrue here, including: Alter S. Reiss, Anatoly Belilovsky, Brian Dolton, David Steffen, Gareth D Jones, Gary Cuba, Grayson Bray Morris, J. Kathleen Cheney, Laurel Amberdine, Matt Rotundo, Melissa Mead, Patty Jansen, Rick Novy, Ronald D Ferguson, S. Boyd Taylor, Sylvia Spruck Wrigley, and Vylar Kaftan. Also to my sister, editor Su Reid-St.John, who made several improvements by catching goofs in my text before this was posted.

Photo by MacQ

May 21, 2012

Eight Ways to Organize Information and Ideas

1. In my last article, I talked about the huge benefits we can get from funneling information into an outline. Outlining is helpful for a single person (or sometimes a group) to take a lot of information and make regular use out of it. In this follow-up, I’ll talk about other ways to organize a lot of information or ideas, with pros and cons for each.

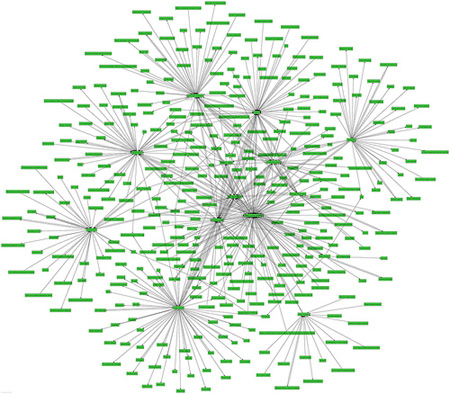

Wikipedia Concept Map by Juhan Sonin

2. One option is to remember only whatever happens to stick and be reconciled to forgetting a lot of it. This is often our go-to method, for instance if we watch a documentary out of personal interest. It’s perfectly appropriate if we’re not going to need to put the information to direct use but just want to be exposed to it. For instance, I haven’t done anything specific with what I’ve learned from seeing God Grew Tired of Us, but it added to my perspective and my understanding of other people’s lives, and I’m glad I saw it.

3. We can go over it repeatedly until it’s memorized, which is the way, for example, we try to learn foreign languages, because we need that information be available in our heads. If I want to go to France and speak with other people there, it’s not going to help me to have a laptop with me so that I can look up verbs > subjunctive > irregular in my outline to help me say “Would it be a problem if I were to go along?”

4. We can leave it unorganized and just go through the whole thing when we need something from it, as most of us do or have done with notes from classes. This can go along with the memorizing approach, but it’s very inefficient if you want to be able to interact with your information and find things in it quickly.

5. We can use a tagging system in which we label each item with all the terms that apply to it, so that in addition to looking at the information in order, we can also filter down to just a particular kind. This is the way most blogs are organized. For instance, you can click the word “organization” in the tags for this post to see other posts of mine on the subject of organization.

6. We can index it, as we traditionally do with books, but this is a lot of work, and my experience is that indexes aren’t used very often unless a person knows exactly what they’re looking for.

7. If it’s information that we can somehow make into images, we can visualize it as a chart, graph, map, or diagram. Visualizing information usually means losing or hiding most of the detail and often comes with a limit as to how much information you can add, but it creates a big-picture perspective that can be difficult to come by otherwise. One approach to this is drawing or using software to create a “concept map” (also called a “mind map” or “spray diagram”). There’s an introduction to concept maps at http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newISS_01.htm . I must say that I don’t find concept maps especially useful, but they do seem to be fairly popular. If you get a lot of use out of them, your commenting to offer perspective on the issue would be much appreciated.

8. Finally, we can link it, making connections between one chunk of information and other chunks of information. This is a lot of work, but it creates an environment in which we can flow freely from topic to another. Wikipedia (one of my favorite inventions of all time) and other wikis are organized this way, as is the Internet as a whole. It’s useful for information that keeps expanding, especially from different sources, but it’s nearly impossible to link together all the topics that might be related to each other, and it’s hard to find all of the pieces of any one particular area of knowledge; more often, we’re just led from one subject to another related one with no clear end in sight.

All of these approaches have their uses, but my sense is that outlining is the most underused and under-rated tool in the toolbox. If you’re comfortable with computers and have a mass of information or ideas to sort out, it may be just the thing to toss into your organizational mix.

May 18, 2012

How to Make Sense of a Flood of Information and Ideas

When I began to get serious about professional speaking, it was clear to me that regardless of how much I knew about my subject (teaching people how to change), that I had a lot of research still to do–on professional speaking itself. I needed to get much more familiar with types of events, presentation practices, ways to structure talks, compensation, how to deliver the most value for my audiences, and so on. To that end, I started reading books and articles and hunting down videos to watch online. A flood of information began pouring in, and I found myself coming up with a steady stream of ideas for presentations and ways to connect. The problem then was to find a way to make sure I could use everything I was getting, that it wouldn’t get lost or forgotten.

This is the same situation a person runs into, for example, when writing a book, getting immersed in a new topic, planning a business, or organizing a large event. What do you do with all this information?

You outline it.

Why an outline?

To make use of a lot of information, we need to categorize it. This isn’t just for convenience: our brains are used to dealing with just a few things at a time. (The limit used to be thought to be around 7 items, but it turns out it’s probably more like 4: for example, see http://www.livescience.com/2493-mind-limit-4.html .) So if I have 2,000 individual pieces of information to keep track of, I’m going to want to group them into few enough categories that I can easily navigate through the whole thing. Within those categories, I’m still going to have hundreds of items, so I need to group that information further, and so forth. These categories-within-categories make up an outline.

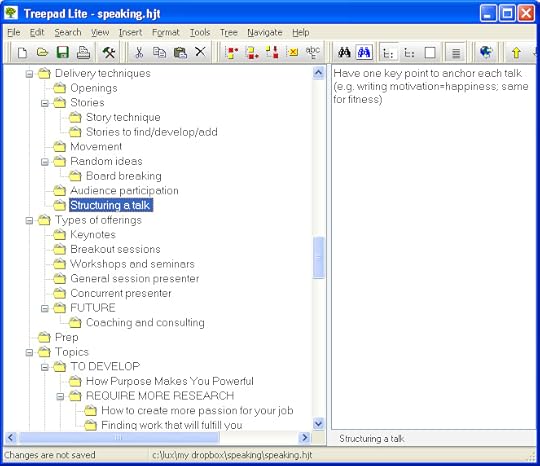

Once I have my outline, I may have sections that have a special purpose, like a to do list (or items to add to my main task management system, whatever that is), questions that need to be answered, people I’ll want to remember, and so on. The great thing about using an outline for this is that I can find a piece of information whether I know what I’m looking for or not. For example, here’s a screen shot of part of my outline for my speaking business. You can click on it to view it at full size. Each of the little folder icons represents either a category or a chunk of text (or both).

If I’m putting a new topic together, I’ll be looking at my Speaking section under “delivery techniques,” and I’ll be reminded of the tip about having one key point under “structuring a talk.” If, in a different situation, I’m trying to remember exactly what I thought was important about structuring a talk, my outline will make the information easy to find.

Creating the outline is easy

The actual work involved in putting an outline together isn’t hard, because all you have to do is take one thing at a time and decide where you want to put it. If you don’t already have a good place to put it, you make one up. If one part of your outline is getting too full, you break things down into a greater level of detail. If you have too many branches off of one item, you can group them into larger branches, for instance grouping a bunch of recipe ideas for an event into desserts, entrees, side dishes, and so on.

When I’m gathering information or brainstorming ideas, I usually start by taking down a whole lot of unstructured notes. Whenever I’m ready, whether with all of it at once or just one section, I can start putting those notes into an outline.

Of course, you’ll need something to create the outline in. Less complicated outlines can be kept in a word processing program, but what’s more useful is a specialized kind of program called an outliner. The screen shot you see is of a free one I’ve been using called Treepad Lite, which you can get at www.treepad.com . There are more sophisticated outliners too, and I’ll probably upgrade to one of those before too long. Suggestions are welcome.

Outlines are made up of “nodes.” Each node can contain information and can also contain other nodes. With a good outliner program, you can have as many levels of nodes-within-nodes as you need, which means that you can branch or group or expand your outline however and whenever you want to.

If the information you’re gathering is meant to end up as a single written piece in the end, I can wholeheartedly recommend Scrivener, which is a kind of hybrid outliner-word processor that can take a lot of material and help you cook it down into something that flows from beginning to end.

In the second article in this series, I’ll talk about the alternatives to outlining and the pros and cons of each.

Making Sense of a Flood of Information and Ideas

When I began to get serious about professional speaking, it was clear to me that regardless of how much I knew about my subject (teaching people how to change), that I had a lot of research still to do–on professional speaking itself. I needed to get much more familiar with types of events, presentation practices, ways to structure talks, compensation, how to deliver the most value for my audiences, and so on. To that end, I started reading books and articles and hunting down videos to watch online. A flood of information began pouring in, and I found myself coming up with a steady stream of ideas for presentations and ways to connect. The problem then was to find a way to make sure I could use everything I was getting, that it wouldn’t get lost or forgotten.

This is the same situation a person runs into, for example, when writing a book, getting immersed in a new topic, planning a business, or organizing a large event. What do you do with all this information?

You outline it.

Why an outline?

To make use of a lot of information, we need to categorize it. This isn’t just for convenience: our brains are used to dealing with just a few things at a time. (The limit used to be thought to be around 7 items, but it turns out it’s probably more like 4: for example, see http://www.livescience.com/2493-mind-limit-4.html .) So if I have 2,000 individual pieces of information to keep track of, I’m going to want to group them into few enough categories that I can easily navigate through the whole thing. Within those categories, I’m still going to have hundreds of items, so I need to group that information further, and so forth. These categories-within-categories make up an outline.

Once I have my outline, I may have sections that have a special purpose, like a to do list (or items to add to my main task management system, whatever that is), questions that need to be answered, people I’ll want to remember, and so on. The great thing about using an outline for this is that I can find a piece of information whether I know what I’m looking for or not. For example, here’s a screen shot of part of my outline for my speaking business. You can click on it to view it at full size. Each of the little folder icons represents either a category or a chunk of text (or both).

If I’m putting a new topic together, I’ll be looking at my Speaking section under “delivery techniques,” and I’ll be reminded of the tip about having one key point under “structuring a talk.” If, in a different situation, I’m trying to remember exactly what I thought was important about structuring a talk, my outline will make the information easy to find.

Creating the outline is easy

The actual work involved in putting an outline together isn’t hard, because all you have to do is take one thing at a time and decide where you want to put it. If you don’t already have a good place to put it, you make one up. If one part of your outline is getting too full, you break things down into a greater level of detail. If you have too many branches off of one item, you can group them into larger branches, for instance grouping a bunch of recipe ideas for an event into desserts, entrees, side dishes, and so on.

When I’m gathering information or brainstorming ideas, I usually start by taking down a whole lot of unstructured notes. Whenever I’m ready, whether with all of it at once or just one section, I can start putting those notes into an outline.

Of course, you’ll need something to create the outline in. Less complicated outlines can be kept in a word processing program, but what’s more useful is a specialized kind of program called an outliner. The screen shot you see is of a free one I’ve been using called Treepad Lite, which you can get at www.treepad.com . There are more sophisticated outliners too, and I’ll probably upgrade to one of those before too long. Suggestions are welcome.

Outlines are made up of “nodes.” Each node can contain information and can also contain other nodes. With a good outliner program, you can have as many levels of nodes-within-nodes as you need, which means that you can branch or group or expand your outline however and whenever you want to.

If the information you’re gathering is meant to end up as a single written piece in the end, I can wholeheartedly recommend Scrivener, which is a kind of hybrid outliner-word processor that can take a lot of material and help you cook it down into something that flows from beginning to end.

In the second article in this series, I’ll talk about the alternatives to outlining and the pros and cons of each.

May 16, 2012

Vicki Hoefle: End Temper Tantrums, In 4 Words or Less

Earlier this year, my partner Janine and I had the chance to study with parenting educator Vicki Hoefle, whose Parenting On Track™ program, with its roots in Adlerian psychology, strikes off in a completely different–and more effective–direction than any approach to parenting I had ever come across. Vicki has kindly made some of her parenting articles available to me to reprint here. If you’re interested in the topic or have questions, please comment to help guide me in choices for future posts.

This article originally appeared at http://www.parentingontrack.com/2008/06/end-temper-tantrums/ .

End Temper Tantrums, In 4 Words or Less

Vicki Hoefle

No, you are not going to “give in” to them! No, you are not going to “naughty chair” them. No, you are not going to “talk about it”. What you ARE going to do, is add three of the most POWERFUL words on the planet to the word YES and turn temper tantrum -ing toddlers (or teens for that matter) into patient, cooperative thoughtful family members.

Don’t believe me? Well here is a true story that demonstrates just how effective these 4 words are, when used correctly.

I was walking with my good friend and her two children ages 1 and 2, whom I absolutely adore, and the family dogs. The goal was to get some exercise and reconnect with each other while getting the kids out of the house for some much needed fresh air and sunshine. Unfortunately, once we started walking, the kids started in with some classic demands and, well, here is what happened…

It started out with a “Waaaa” from the one-year-old and several whiny “I waaaant toooo waaaalk” from the two-year-old. Like most parents, my friend eventually gave in and let the two-year-old walk, and, as you know, if you let one out, you have to let the other one out, right?

I was immediately impressed with my friend’s circus-like talent. She started by holding the one-year-old in her arms, trying all the while to push the stroller while keeping the other child on the sidewalk. Soon enough, she was juggling two kids, a stroller, and the dogs in beautiful, chaotic synchronization. Amazed… if not utterly stunned by what she had taken on, I remained quiet and observed. And yes, of course, I eventually offered to help.

No doubt some of you recognize this story and are smiling, nodding, or even shaking your head with that blank, shell-shocked look on your face. Well, keep reading because there IS relief to this timeless riddle.

Alas, the girls did not want to walk OR be held OR do anything else for very long. And, it soon became clear that changing their position up, down, over, around and through, wasn’t even their GOAL. What they really wanted was to keep their mommy busy with them, at the expense of everything else – including visiting with me.

Very quickly, neither my friend nor I were having any fun. I had lost interest in the endless circus act, and we were not able to talk and connect with these two ruckus munchkins demanding all of the attention. So, we soon retreated home and the walk was officially over.

The next day when my friend and I had a quiet moment, we discussed the events that had unfolded the day before. We talked about how quickly the walk had degenerated from a time for two adult friends to connect, into a circus routine with the children in the center ring, running the show.

As you probably know, this is a situation parents find themselves in quite often. If you’re just now expecting your first child, or are thinking about having children, all you have to do is look around the next time you are in the grocery store. You’ll see moms carrying the baby, cajoling the toddler, or bouncing the baby while trying to make it through at least putting the essentials in the cart.

And then there are fathers, gallantly trying to avoid a public tantrum by giving in to their little one’s pleading cries for gum, candy or treats. And, as in my dear friend’s case, there are constant accommodations in response to pleas for freedom from or return to the stroller.

In the Parenting On Track™ program we refer to this place as The Slippery Slope – that place where parents find themselves when they know at any minute things could go from good to bad, or from bad to really bad!

So, what’s a well-meaning, law-abiding parent to do?

It’s all about training. We can either train our kids to believe that life is all about them, and that it is their job to keep us busy with them, OR we can train our kids in the fine arts of patience, respect, flexibility, cooperation, and manners – arts that are also valuable life skills that will pay dividends faster than you can say “play date!”

OK, I get it. But just HOW does one do teach these fine arts?

Start small by creating opportunities from everyday life, and for those moments that catch you off guard try this simple Parenting On Track™ strategy called “Yes, As soon as…” Quick, easy, and highly adaptable, using this strategy results in simple, but effective exchanges like this:

Child: “Can I walk?”

Parent: “Yes, as soon as we get to our road.”

Child: “Can I watch TV?”

Parent: “Yes, as soon as you finish your homework.”

Child: “Can I have a cookie?”

Parent: “Yes, as soon as you eat something healthy.”

The tantrums and the whining usually begin when we tell our children, “No.” And, it ends when we either give in or get mad. Neither one breaks the cycle or teaches our children anything useful. So, say “Yes,” instead, AND… make sure that “Yes” is part of an agreement between you and your child. You agree to let your child do something or have something they want, when they prove to you that they can handle the privilege.

If you have trouble getting started, remember this.

It may not work the first time, and is not intended to stand alone, so you should also:

Try to incorporate the Crucial C’s (Chapter 9, Parenting On Track™ Home Program) with all the strategies you use.

Have faith in your kids – they can handle both the disappointments and privileges.

Have your kids help you find solutions to problems if you are stuck.

And always, always, take the time to make a plan.

Now, just close your eyes, take a deep breath, and imagine what it will be like if, after 6 months, your family was tantrum-free. It’s all worth considering isn’t it?

Image by Susan NYC

May 14, 2012

Sudden perspective shifts

One of the things that fascinates me and that I continue to try to fully understand is the sudden perspective shift that changes everything. For instance, if you’ve ever read Les Miserables (or seen the musical or a movie of the story, even), you’ll remember the moment when Jean Valjean, an escaped convict, has been caught by the authorities while is was fleeing the home of a bishop who sheltered him and is in possession of valuables he stole from the bishop. The bishop, instead of accusing Valjean, tells the authorities that the stolen goods are gifts, and even adds to them. This utterly unexpected turn changes Valjean’s perspective for the rest of his life–much for the better, I might add.

One of the things that fascinates me and that I continue to try to fully understand is the sudden perspective shift that changes everything. For instance, if you’ve ever read Les Miserables (or seen the musical or a movie of the story, even), you’ll remember the moment when Jean Valjean, an escaped convict, has been caught by the authorities while is was fleeing the home of a bishop who sheltered him and is in possession of valuables he stole from the bishop. The bishop, instead of accusing Valjean, tells the authorities that the stolen goods are gifts, and even adds to them. This utterly unexpected turn changes Valjean’s perspective for the rest of his life–much for the better, I might add.

But Valjean is fictional, and while the example is fascinating, though there’s much to think about in the debate that plays out in the rest of the story (what I read of it–while I know it’s not considered respectable to purposely put aside a classic, Hugo’s novel wanders too much to keep me engaged. He lost me after the whole Napoleon interlude).

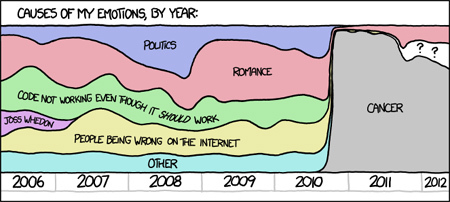

Cartoonist Randall Munroe, whose work I often find absolutely brilliant (for instance, see my post on his Zombie Marie Curie comic from about a year ago), recently posted a cartoon that illustrated, literally and dramatically, what a real perspective shift is like, with plenty of dark humor. Here is that comic:

You may be worried to know that this cartoon is based on life, but Munroe, who is usually pretty private, kindly shares with us that “She’s doing well.”

May 9, 2012

How Do You Research Characters and Settings So That They Feel Real?

Old Vermont barns like this one were part of my experience I wanted to use in the setting for my novel of curse-keeping in rural Vermont, Family Skulls (see left sidebar)

I try to limit the number of posts I make on the craft of fiction writing, because while I’ve been seeing some great success in my writing, it’s not as though I’ve written the Great American Novel and hit the bestseller lists, so advice on how to write a story seems like something I should be careful not to give out too much of. However, a reader recently wrote to me saying she was concerned that she might not be able to learn enough about her characters and settings to write a novel that feels real, and asking what kind of research I do when writing fiction to make sure that these elements work. Feeling that I had some useful information on the subject, I replied. Here’s what I wrote:

Based on my own experience and on many discussions with other writers, there seem to be a lot of different approaches to researching character and setting. Some of us just dive right in and either stop to do research as necessary or make notes about what we need to research and just keep writing around the blanks. Personally I’m not a fan of putting in a blank and expecting to fill in with research later, because I think good research can weave itself deeply into the story, but I can’t deny that it works for some good writers.

Using research to make a story work well and feel real isn’t especially difficult, but it does take time and effort.

Approaches for characters

I’d suggest taking different approaches for characters and setting. For characters, unless you’re the kind of person who (like me) likes to try to draw characters out while writing the story, I’d suggest putting down some key information about each major character first. Basic life facts and physical information are important, of course–What are their hair colors? How strong or weak, heavy or light are they? What kinds of medical problems have they had to go through? How tall or short are they? What were their families like as children, and who was in those families? What are their family or living situations like now? How do they get along with family members in the present? How far have they gotten in school? How did they do? What job, if any, do they have?

Even more importantly, though, you can delve into what drives them. I don’t think it’s necessarily important to know what a character’s favorite color is or what that character ate for breakfast unless that’s very meaningful to who they are or to the story–though some writers disagree and feel that this kind of extreme detail is worth gathering. For my money, though, what’s important is what the character desires, what they’re afraid of, what their doubts are, what kinds of situations get under their skin, and that kind of thing.

Strengths and schemas

I often use strengths and schemas, at least informally, to flesh out characters. The 36 strengths outlined by Marcus Buckingham, et al. (see http://www.strengthstest.com/theme_summary.php ) are one good way to find out what characters are good at. The 18 early maladaptive schemas from schema therapy (see http://www.lucreid.com/?page_id=1292 ) can be used to find at least one major personality flaw for each character. Real people have multiple strengths and usually multiple schemas, though some may be milder than others. Characters don’t necessarily have to be fleshed out with a cocktail of five strengths and three schemas, for instance, unless it’s really necessary to get that deep to figure out what they’ll do.

Have reasons for your choices

One piece of this process that seems essential to me (and that I forgot to mention to my correspondent on the first pass) is that I don’t see any point in coming up with arbitrary choices. I’d advise choosing character details because they grab you, because they make the character more interesting and complex, because they’ll drive the story, or because they make an interesting cocktail with other characteristics. If your character creation process contains steps like “I guess she’ll have been brought up by a single mom, because I know there are a lot of single moms,” then I suspect you won’t get much juice out of that fact of her upbringing. If you say, though, “I guess she’ll have been brought up by a single mom, and the mom was an alcoholic, so my character had to be the parent to her own mom as she was growing up,” or “I guess she’ll have been brought up by a single mom, being told her father was dead, and then in the story her father will show up at some crucial point when she can’t afford to spare any attention to connect with him.” … well, then maybe you’ve got something.

Personally, I tend to try to let characters emerge organically as I write them, and only stop and question myself about them when they’re not already coming alive. However, this approach takes some practice to work well, doesn’t suit everyone, and may not be ideal anyway. My suggestion in regard to how to come up with characters, as with everything else, is to try everything … then spend a few years getting better at the techniques you decided to use and try everything again. Write, grow, repeat.

Approaches for settings

For settings, I’d suggest starting with a place you have easy access to if possible and paying close attention to the sights, sounds, smells, and physical experience of being in that place. If that’s not practical, it’s worth digging up photos, videos, articles, or other materials that give you a lot of physical specifics. Writing comes alive when it’s full of fresh, unusual, accurate sensory details–and ideally not just sight and sound, but all the senses. If you go too far with this, it begins to get overwhelming, but one or two good sensory impressions per page really pack a punch.

The facts about a location are easier: you can use Google Maps or Google Earth to find out how things are laid out, look up construction of houses or how an office is furnished, etc. I tend to do a lot of research looking for images and videos, because they give me much more of a feeling of being in a place than a simple description.

A couple of writing books you might really like, in case you haven’t already read them, are Orson Scott Card’s Characters and Viewpoint and Stephen King’s On Writing. Between the two of them, they can give you a lot of tools, explanations, and confidence.

Photo by Beth M527

Quinn Reid's Blog

- Quinn Reid's profile

- 6 followers