Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 21

January 22, 2018

The Odyssey in the 21st Century

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Well into the 19th century (and later, in many places), a gentleman’s education—to the extent he had one—consisted mainly of studying Greek and Latin.* This is why, when we read 18th and 19th C books written by men, we come upon untranslated chunks of Greek and Latin. An educated gentleman, it was assumed, would easily understand material he’d learned by rote in school. In a number of my books, I mention this emphasis on Latin and Greek.

All the same, very few people, even in the 19th century, read Homer’s Odyssey in the original Greek. For centuries, scholars and poets have tackled the work, making that tricky ancient Greek accessible, not only to those without a classical education, but also educated persons who found Homer very hard going.

My epigraph for the Prologue of Dukes Prefer Blondes is the beginning of The Odyssey as translated by William Cowper in 1791:

Muse, make the man thy theme, for shrewdness famed

And genius versatile

These are the first lines of the Invocation of the Muse, which we later learn the hero is trying to construe from the Greek. As young Oliver Radford realizes, there’s more than one way to read the poem. Here’s how T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia) began:

Odysseus and the Sirens 1829

Goddess-Daughter of Zeus

Odysseus and the Sirens 1829

Goddess-Daughter of ZeusSustain for Me

This Song of the Various-Minded Man…

Wikipedia offers a very long list of English translations, beginning with George Chapman’s of 1615:

The man, O Muse, inform, that many a way

Wound with his wisdom to his wished stay;

We go on to find Odysseus described as “that prudent Hero,” “The man for wisdom’s various arts renown’d,” “the crafty man,” “the man full of resources,” and on and on. If you want a sense of how not easy it is to translate Homer’s epic, please do scroll down the Wikipedia page to the section on The Odyssey .

A short time ago, Susan sent me the opening of a a new translation of The Odyssey , by Emily Wilson , the first English translation by a woman.

Robbing the cattle of Helios

Tell me about a complicated man.

Robbing the cattle of Helios

Tell me about a complicated man.Muse, tell me how he wandered and was lost

when he had wrecked the holy town of Troy;

and where he went, and who he met, the pain

he suffered in the storms at sea, and how

he worked to save his life and bring his men

back home. He failed to keep them safe; poor fools,

they ate the Sun God’s cattle, and the god

kept them from home. Now goddess, child of Zeus,

tell the old story for our modern times.

Find the beginning.

After reading these lines, I ordered the book. Though I’m saving a full read for my late winter sojourn in the South, it’s been hard for this Nerdy History Girl to resist dipping into it. The introduction is an eye-opener, the perfect prelude to the new translation, which IMO is a knockout. As to the story itself, as translation after translation demonstrates, it never gets old.

Waterhouse, Circe Invidiosa 1892

Waterhouse, Circe Invidiosa 1892

*This isn’t to say that boys and men learnt nothing else. Indeed, a gentleman, not having a job to go to every day to support his family, had the leisure to investigate a wide variety of subjects. Many gentlemen were true polymaths. They were adept in multiple languages, performed agricultural and scientific experiments, attempted to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs, developed early forms of photography, and so on.

Images: Book cover for The Odyssey by Emily Wilson; Pellegrino Tebaldi, The companions of Odysseus rob the cattle of Helios 1554-1556; Bruckmann, Alexander, Odysseus and the Sirens 1829;

J.M. Waterhouse, Circe Invidiosa 1892 from the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia ( this image via Wikimedia Commons ).

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on January 22, 2018 21:30

January 21, 2018

A Backward Letter from Jane Austen, 1817

Susan reporting,

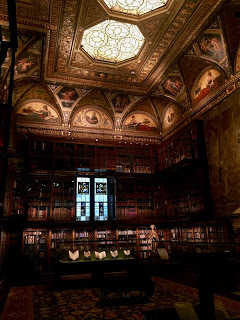

Susan reporting,Whenever I'm in New York, I always try to stop by The Morgan Library to see what treasures from their extraordinary collection have been rotated onto display. As usual, I wasn't disappointed. Among the current exhibits are a score by Mozart, a Gutenberg Bible, a proclamation from George Washington, letters from Alexander Hamilton and Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton (!!!), and this wonderful short letter from Jane Austen. These items and others are part of the current Treasures from the Vault exhibition, on display through March 11, 2018.

At first glance, the words appear to be beautifully written gibberish. But there's a trick to reading it: each word is spelled backward. According to the Library's placard, the letter was written by Austen to her eight-year-old niece Cassandra Esten Austen, the daughter of her brother Charles. The code is a bit challenging, but not so difficult that a clever eight-year-old (and being Jane Austen's niece, Cassandra must have been clever) couldn't decipher it. I also imagine Cassandra treasured it, too; her aunt died only six months later, leaving her final novel, Sanditon, unfinished.

I'm not providing a translation (the Library didn't either), so you can try to figure it out for yourselves. It begins "My dear Cassy I wish you a happy new year" and is signed "Your affectionate aunt Jane Austen." What lies between is up to you. Please click on the image to enlarge.

Above: Jane Austen (1775-1817) Autograph letter, written backward, to her niece Cassandra Austen, signed and dated Notwahc [Chawton], 8 January 1817, The Morgan Library.

Below: Mr. Morgan's Library, The Morgan Library

Photos ©2018 Susan Holloway Scott

Published on January 21, 2018 17:00

January 20, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of January 14, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Bullet-stopping Bibles .

• How an earthenware jug can be a radical object.

• Why did Charles Dickens have a personal postbox?

• A seldom-seen part of New York City : the vanishing towns along Hook Creek.

• An overlooked benefactress: new research discoveries about who paid for Alexander Hamilton's education .

• Image: Cross-section of a Regency-era townhouse in Brunswick Square.

• Katherine of Aragon's prayer book.

• How the newly rediscovered kitchen at Monticello fits into the history of upper-class dining in the west.

• Empress Josephine and the creation of Malmaison .

• Two suns? No, it's a supernova drawn in Kashmir over 6,000 years ago.

• A graveyard of ghost ships near Coney Island.

• The tattooist of Auschwitz - and his secret love.

• Image: This is the world's oldest known woven garment , dating from 3482-3103 BC.

• The countess, the gout , and the spider.

• Then and now: fifteen historic New York scenes .

• Unicorns in an 18thc Persian medical manual.

• Image: Cutaway reconstruction of late 12thc polygonal keep at Conisbrough Castle, South Yorkshire.

• Distilling the essence of Heaven: how alcohol could defeat the Antichrist (at least in the 16thc.)

• A rare cast & chased gold medal of Queen Elizabeth I that was likely a gift from the queen to a favored courtier or ally.

• Unbelievable images from Weird (er, World) War Two.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on January 20, 2018 14:00

January 18, 2018

Friday Video: The Wedding of Princess Elizabeth & Philip Mountbatten, 1947

Susan reporting,

This is for all of you out there who are engrossed in The Crown on Netflix. Here's a short newsreel segment with the highlights of the wedding of Princess Elizabeth and Philip Mountbatten on November 20, 1947. As grainy as this black & white footage is today, how exciting it must have been to people in the cinema in those pre-television days - and how very different from the second-by-second broadcast of the last royal wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge.

Published on January 18, 2018 21:00

January 15, 2018

A Newly Discovered Painting of Gen. George Washington's Headquarters Tent, 1782

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,"National treasure" is a heady designation, but I can't think of any artifact that deserves it more than George Washington's headquarters tent, middle left, now the star of the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, PA. The old tent's once-stout canvas is worn so thin that it now requires an elaborate internal substructure to support it, and so fragile that it can only be shown to visitors a limited number of minutes a day. Yet there are few objects that are both so weighted with history and so emotionally evocative of a long-gone time and spirit.

I've written before in detail about the tent's history here , and about the hand-sewn replica of it (the "stunt double" used in the museum's film) made by the tailors of Colonial Williamsburg here. For visitors to the Philadelphia area, the tent has become a must-see - though I should warn you that everyone I've taken to see it has been overwhelmed to the point of patriotic teariness.

While the actual tent still exists, as well as numerous descriptions of it dating from the Revolution, there wasn't an 18thc image that showed it in use in the field. However, in one of those fortuitous discoveries that make history so special (and delights viewers of Antiques Road Show), an 18thc watercolor showing the tent suddenly appeared at auction last spring, only weeks after the MoAR had opened. While the auction house had labeled it as simply a "Revolutionary War Camp Scene," to Dr. Philip Mead, Chief Historian and Director of Curatorial Affairs for the Museum, recognized the tent as once. Fortunately, no other potential buyers did as well, and the Museum was able to acquire the drawing for its permanent collection.

The watercolor is long and narrow - about 12" high and seven feet in length, and far too long to capture in its entirety here - consisting of multiple sheets joined together to create a panorama of the Continental Army's 1782 encampment at Verplanck's Point in New York's Hudson Valley. (The single sheet, below, shows the visible joinings between pages.) Rows and rows of the soldiers' small, peeked tents are depicted in precise detail, right, as are the more elaborate tents of the officers. Set apart from the others and on a small hill in a position both commanding and unmistakable, is Washington's field tent, complete with its decorative entryway, above left.

"We have no photographs of this army, and suddenly here is the equivalent of Google Street View," said Dr. Mead. "Looking at it, you feel like you are walking right into the past."

But the tent and the military landscape surrounding it are only part of the watercolor's story. Additional study, analysis, and preservation confirmed that the scene was painted by Pierre L'Enfant, the French-born military engineer who traveled with the Continental Army during the war. L'Enfant was a man of many talents; he also designed the plan for Washington, DC, and the Diamond Eagle of the Society of Cincinnati (featured in my blog here.) A skilled artist, L'Enfant's eye for detail and accuracy was remarkable. Although this same landscape along the Hudson River today includes a few modern buildings, it's surprisingly recognizable from L'Enfant's painting, over 235 years later.

The watercolor is currently on display through February 19 in the exhibition "Among His Troops" at the Museum of the American Revolution. In addition to other artifacts used at the 1782 encampment, the exhibition includes the only other known L'Enfant panorama, a view of West Point, also painted in 1782. I'll be writing more about this second painting later this week.

Click here for more information about the exhibition.

Many thanks to Phil Mead and Scott Stephenson for the early tour of the exhibition, and to Alex McKechnie for her assistance.

Photographs courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution.

Published on January 15, 2018 21:00

January 14, 2018

Blonde Lace on the 19th Century Red Carpet

1833 Bridal Ensemble

1833 Bridal Ensemble

Loretta reports:

Some of my readers have asked about blonde lace.

Certain of the ladies’ magazines listed who wore what at court events. If you type “blonde” into the search box for this 1831 Royal Lady’s Magazine , you will notice that nearly every single lady wore blonde or blonde lace to the Queen’s Drawing Rooms.

Naturally, then, blonde features in my heroines’ clothing. And quite naturally also, readers have asked about it, some puzzled especially by the notion of “black blonde.”

Blonde lace is a silk bobbin lace. A search on YouTube will show it being made, and give you an idea why the handmade version was so very expensive and highly prized. The “blonde” part refers to the silk’s natural color. Once a way was found to make the silk stronger, it could be lightened, for a white blonde, and dyed for black blonde.

1833 Carriage Dress

1833 Carriage Dress

Sleuthing online, one ends in a confused state. “Next to Chantilly the blondes are the most important among the silk laces .” Elsewhere, we’re told that Chantilly is a blonde lace. My impression is, the blonde made in Chantilly was considered superior. I await elucidation by textile experts.

For the purposes of my books, this isn’t crucial, any more than it was crucial for the magazines to distinguish. For the purposes of A Duke in Shining Armor in particular, what you’d probably rather see are examples.

Beechey, Queen Adelaide

Beechey, Queen Adelaide

The bridal ensemble (at top) I gave my heroine Olympia includes “a pelerine of blond extending over the sleeves” and “a deep veil of blond surmounting the coiffure, and descending below the waist.”

The “French” dress she donned at the inn was based on several images, but this pink carriage dress from the Magazine of the Beau Monde, though listed for August 1833 (my story is set in June of that year), about covers what I had in mind. She wears “a black blond pelerine with square falling collar, the points descending low down the skirt and fastened in front with light green ribbon noeuds.”

However, portraits capture the look of the lace much better than the stiff, stylized fashion prints. Queen Adelaide (consort of King William IV, monarch at the time of my story) is wearing blonde lace in this image from about 1831.

Giovanina Pacini

Giovanina Pacini

Giovanina Pacini, the eldest daughter of the Italian composer Giovanni Pacini wears what I'm pretty sure is black blonde in this 1831 image.

You can see a sample of Belgian Bobbin Lace in this lappet.

And here is a sample of French Pillow-made Silk Blonde .

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on January 14, 2018 21:30

January 13, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of January 7, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Finding Mary Wordsworth's voice.

• From Boudicca to the Amazons: warrior women.

• What finally drove Ulysses Grant to write his memoirs, and what Mark Twain had to do with it.

• Nineteenth century umbrella etiquette.

• Conservation and detective work: tiny scraps of paper found on Blackbeard's ship lead to ID of book on board.

• Image: Rare hand-knitted Tudor child's mitten.

• A human heart buried separately in a lead box in medieval Ireland.

• Why did this prosperous 18thc butcher own 20 pairs of sheets, 10 pillowcases, and 36 napkins and towels?

• The toy theatre publishers of Old Street, London.

•

• Spurious quotations attributed to George Washington.

• Christmas and Twelfth Night gifts for the British royal children in 1750.

• Image: A baker's loaf from Pompeii, carbonized in the eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD.

• Louisa May Alcott and her brief, harrowing career as a Civil War nurse.

• Distaff Lane: How a London street has changed over the centuries.

• The secrets of Victorian memorial hairwork .

• Image: The sewing bird , an 1850s invention designed to ease the task of hand-sewing.

• The Guild for Women Binders , a collective of female artisans who created gorgeous, hand-crafted book bindings, 1898-1904.

• Mealtimes in the Regency era.

• How to sail a big ship like the USS Constitution .

• King Chloroform and Queen Gangrene: critical care during the American Civil War.

• The story behind the most famous " morning after " scene in art history.

Image: Napoleon's toothbrush with a silvergilt handle, 1790.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on January 13, 2018 14:00

January 11, 2018

Friday Video: Romance at the Strand

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:No, I don’t mean the Strand in London, though that would be nice, too.

The post title refers to the Strand Bookstore in New York, where, as part of my book tour for A Duke in Shining Armor , I participated in a panel dealing with the romance genre and the respect it does and doesn’t get. A column in the Washington Post in August inspired the panel.

Some of you, e.g., Twitter followers and subscribers to my website blog , may have already seen the video. Some of you will look at the run time and say, “Yikes! An hour?” But as you see in the image, there is laughter, and that’s not the only time. So, if you'd like to hear a group of writers talk and crack jokes about the worlds they and their characters inhabit, both imaginary and actual, you might want to pour a glass of your favorite beverage or dish out some ice cream or pour your favorite flavor enhancer on a bowl of popcorn—or all of these and others in a random order or even simultaneously—and spend some time with us.

Video: Romance and Respect , Strand Bookstore

Image: Still from the Strand video. L-R: Denny S. Bryce (moderator), Tessa Bailey, Loretta Chase, Tracey Livesay, Megan Frampton, Joanna Shupe

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on January 11, 2018 21:30

January 10, 2018

Keeping Warm in the 18thc: Buzaglo Stoves, Revisted

Susan reporting:

Susan reporting:After my recent post about coping with a cold winter in 18thc America, I decided to revisit and update this post from several years ago, featuring the very latest in Georgian heating.

Perhaps the most prominent building in Colonial Williamsburg is the reconstructed Governor's Palace. The palace was the official residence of Virginia's royal governors, and also served to bring royal grandeur to the colony. The governors reflected the king's majesty through rich furnishings, an imposing display of weapons in the front hall and staircase, lavish entertaining, and the latest in technological home improvements. For Norborne Berkeley, 4th Baron Botetourt, and royal governor of Virginia from 1768-1770, this included the towering (it's over seven feet in height) cast-iron stove, left, ordered from London in 1770.

Also called "warming machines," coal-burning cast iron stoves like this were popular in elite homes in London, where they were prized for being effective, fashionable, and exclusive because of their cost. The stoves were the work of a famous inventor of the time named Abraham Buzaglo (1716-1788.) A Moroccan who immigrated to England in 1760, Mr. Buzaglo immediately amazed Londoners with his cast iron warming machines, which he patented in 1765.

Mr. Buzaglo's trade card modestly promised that his stoves "surpass in Utility, Beauty & Goodness any thing hitherto Invented in all Europe". They "cast an equal & agreeable Heat to any Part of the Room, and are not attended by any Stench," with "a bright Fire to be seen at Pleasure." More importantly, the stoves"preserve the Ladies Complexions and Eye Sight" and "warm equally the whole Body, without scorching the Face or Legs," plus "other Advantages too tedious to insert."* The stoves were also considered decorative, covered with lively rococo and classical motifs, and featuring urn-like finials topped with flames.

The warming machines were so popular that they became known by the inventor's name (though incorrectly, if inevitably, pronounced by the English as "Buzz-aglow" rather than "Bu-ZAH-glo".) Buzaglos warmed drafty gracious homes as well as university libraries and the shops of tailors and weavers.

The original stove helped heat the Palace, and was so successful that Lord Botetourt ordered an additional one for the House of Burgesses. When Richmond became the seat of the new commonwealth's government in 1780, the stove was taken across the state to help warm the Richmond Capitol well into the 19thc. In 1933, it was returned to Colonial Williamsburg on a long-term loan, and now can be found on display in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. Two modern reproduction stoves - one is shown right - stand in the ballroom of the Governor's Palace.

The original stove helped heat the Palace, and was so successful that Lord Botetourt ordered an additional one for the House of Burgesses. When Richmond became the seat of the new commonwealth's government in 1780, the stove was taken across the state to help warm the Richmond Capitol well into the 19thc. In 1933, it was returned to Colonial Williamsburg on a long-term loan, and now can be found on display in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. Two modern reproduction stoves - one is shown right - stand in the ballroom of the Governor's Palace.So do Buzaglo stoves work? Modern-day fire and pollution regulations frown on combining coal-burning stoves with crowds of tourists. But to a lady shivering in a silk gown two hundred years ago, I'm sure they were a very welcome upgrade from the sparks, soot, and limited warmth of an open hearth.

And, of course, there must have been all those "other Advantages too tedious to insert."

Above: Buzaglo Warming Machine, c1770, Colonial Williamsburg. Image via Colonial Wiliamsburg Foundation.

Below: Reproduction Buzaglo stove, Colonial Williamsburg, photo ©2010 Susan Holloway Scott* "Hot Air from Cambridge", an article by J.C.T. Oates appearing in The Library

Published on January 10, 2018 21:00

January 6, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of January 1, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Trade cards of old London.

• "I will never be vaccinated again": a teenaged diarist discusses the pain of her inoculation, 1901.

• Abigail Adams persisted: a letter from the then-First Lady defending a black servant from prejudice.

• Obelisks on the move: the manpower and engineering needed to move obelisks in ancient Egypt, Rome, and today.

• How competitive walking captivated Georgian Britain.

• Sewing shrouds : 19thc burial clothes.

• Image: Needlework sampler made English novelist and poet Charlotte Bronte .

• Harnessing the power of baubles and bling .

• " Patriotick Ladies , of Edenton in North Carolina" 1774.

• When the master danced with his cook: a country house Christmas in Dorset.

• The tragedy of prostitution in the Old West.

• Water to drink in the 1690s: fit only for invalids and chickens?

• Account of a very remarkable young musician in 1769 - who happens to be Mozart .

• Image: Women attaching the fabric to the wings of World War One biplanes , 1918.

• The African princess (and Queen Victoria's goddaughter) Sarah Forbes Bonetta .

• Fascinating blog to explore: commentary and transcribed daily diary of a Huguenot girl living in England, 1776.

• How Icelandic readers revel in the post-Christmas flood of gift books .

• Image: Poignant Christmas card from the 38th Welsh Division showing a soldier dreaming of home, 1917.

• A brief history of the clothing and fabric trade in London, 1780-1914.

• Elizabeth Woodville , Queen of England.

• Map & rare book detective work: why experts now don't believe this is one of the first maps of America.

• The key to the Bastille has a place of honor...at George Washington's Mount Vernon.

• Just for fun: GIF: This knight at a Ren Faire took his responsibility to defend people from evil drones very seriously.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on January 06, 2018 14:00