Isabella Bradford's Blog, page 20

February 5, 2018

Eighteenth-Century Time, and Two Tall Clocks That Told It, c1796

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Today, we're all accustomed to lives that are driven and measured by time. Watches, clocks, and cell phones are synchronized in precise unison, and each day we work and play, attend meetings, movies, games, and performances, catch trains and eat meals, rise and sleep, by a clock's measurements.

But it wasn't that way in late 18thc America. Precise measurement of time was an elite luxury. The majority of people didn't own watches or clocks. Even for those with sufficient wealth to possess a watched tucked into a fob pocket or clipped to a chatelaine at the waist, accuracy was variable, and being punctual was subjective. Instead people relied upon more general ways of determining time based on the sun and moon in the sky, or the cries of a watchman, or the still-rare public clock in the tower of a church or other public building. The average workday wasn't nine-to-five; it was from sunrise to sunset, and varied with the seasons.

The two case clocks shown here are the exception. Both are the work of Robert Joyce, a clockmaker who trained and worked in London and Dublin before establishing himself in New York City, where these two clocks were made in the 1790s. Although elegantly encased in gleaming mahogany with inlay work (the ovals of sixteen stars represented the then-number of states in the union). the clocks would have been the epitome of modern technology at the time, with 8-day weight-driven movements. They're also very tall, over ten feet in height. They would have been impossible to ignore, which was likely exactly what the man who commissioned them would have wished.

Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804) was one of the most productive men of his age (or any other, for that matter.) He was a workaholic long before the word existed, and in the course of his short life, he wrote letters by the thousand, juggled complicated matters of government policy and diplomacy, handled precedent-setting-legal cases, and created the basis for the American financial system. It's not surprising that during the Revolution, he became Gen. George Washington's favorite aide-de-camp on his personal staff. Hamilton got things done.

As the new country's first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton oversaw the largest single office in the federal government in the then-capital of Philadelphia, and he expected his clerks and other employees to share his ferocious work ethic. Even during the onslaught of the city's Yellow Fever epidemic in 1793 - a terrifying disease that claimed hundreds of people, rich and poor - many of Hamilton's clerks continued to report for work until the office was officially closed.

By tradition, Hamilton commissioned the clock on the top left for the Bank of New York, which he had established in 1784. Its near-twin on the lower left was made for the First Bank of the United States , lower right, (and more info here about plans to restore it) which Hamilton helped charter in 1791. Both clocks were made about 1797. The two banks were grand, imposing buildings, and the towering clocks would have been designed to fit the financial magnificence. Clocks represented efficiency, an admirable quality in a bank, and a clock of this size and obvious expense would also have suggested prosperity and permanence.

Still, I can't help but imagine the effect that such a clock's size and relentless ticking must have had on the clerks who toiled nearby - a painfully modern reinforcement that time is money, and money time. Each click of the hand must also have been an unending reminder of Hamilton's own determination to squeeze as much as he could from every minute - a daunting expectation in any workplace.

Above left: Tall Case Clock by Robert Joyce, c1796, New-York Historical Society.

Above right: Tall Clock by Robert Joyce, c1797, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lower right: First Bank of the United States, completed 1797; now part of Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia.

Photographs ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott

Read more about Alexander and Eliza Hamilton in my newest historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton, now available everywhere.

Published on February 05, 2018 19:00

Eighteenth-Century Time, and Two Tall Clocks, c1796

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,Today, we're all accustomed to lives that are driven and measured by time. Watches, clocks, and cell phones are synchronized in precise unison, and each day we work and play, attend meetings, movies, games, and performances, catch trains and eat meals, rise and sleep, by a clock's measurements.

But it wasn't that way in late 18thc America. Precise measurement of time was an elite luxury. The majority of people didn't own watches or clocks. Even for those with sufficient wealth to possess a watched tucked into a fob pocket or clipped to a chatelaine at the waist, accuracy was variable, and being punctual was subjective. Instead people relied upon more general ways of determining time based on the sun and moon in the sky, or the cries of a watchman, or the still-rare public clock in the tower of a church or other public building. The average workday wasn't nine-to-five; it was from sunrise to sunset, and varied with the seasons.

The two case clocks shown here are the exception. Both are the work of Robert Joyce, a clockmaker who trained and worked in London and Dublin before establishing himself in New York City, where these two clocks were made in the 1790s. Although elegantly encased in gleaming mahogany with inlay work (the ovals of sixteen stars represented the then-number of states in the union). the clocks would have been the epitome of modern technology at the time, with 8-day weight-driven movements. They're also very tall, over ten feet in height. They would have been impossible to ignore, which was likely exactly what the man who commissioned them would have wished.

Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804) was one of the most productive men of his age (or any other, for that matter.) He was a workaholic long before the word existed, and in the course of his short life, he wrote letters by the thousand, juggled complicated matters of government policy and diplomacy, handled precedent-setting-legal cases, and created the basis for the American financial system. It's not surprising that during the Revolution, he became Gen. George Washington's favorite aide-de-camp on his personal staff. Hamilton got things done.

As the new country's first Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton oversaw the largest single office in the federal government in the then-capital of Philadelphia, and he expected his clerks and other employees to share his ferocious work ethic. Even during the onslaught of the city's Yellow Fever epidemic in 1793 - a terrifying disease that claimed hundreds of people, rich and poor - many of Hamilton's clerks continued to report for work until the office was officially closed.

By tradition, Hamilton commissioned the clock on the top left for the Bank of New York, which he had established in 1784. Its near-twin on the lower left was made for the First Bank of the United States , lower right, which Hamilton helped charter in 1791. Both clocks were made about 1797. The two banks were grand, imposing buildings, and the towering clocks would have been designed to fit the financial magnificence. Clocks represented efficiency, an admirable quality in a bank, and a clock of this size and obvious expense would also have suggested prosperity and permanence.

Still, I can't help but imagine the effect that such a clock's size and relentless ticking must have had on the clerks who toiled nearby - a painfully modern reinforcement that time is money, and money time. Each click of the hand must also have been an unending reminder of Hamilton's own determination to squeeze as much as he could from every minute - a daunting expectation in any workplace.

Above left: Tall Case Clock by Robert Joyce, c1796, New-York Historical Society.

Above right: Tall Clock by Robert Joyce, c1797, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Lower right: First Bank of the United States, completed 1797; now part of Independence National Historical Park, Philadelphia.

Photographs ©2017 Susan Holloway Scott

Read more about Alexander and Eliza Hamilton in my newest historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton, now available everywhere.

Published on February 05, 2018 19:00

February 3, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of January 29, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Before private jets, there were the luxurious private train cars of the Pullman Company.

• The White Cockade : a Jacobite tale.

• The beautiful, forgotten color language of 19thc naturalists.

• "For the sake of the prospect ": experiencing the world from above in the late 18thc.

• Feline dress improvers: the Victorian fashion in bustle-baskets for cats.

• Image: Byron's betrothal ring .

• An old chair in new clothing.

• Little Red Riding Hood in 1810 was much more cautionary.

• Elizabeth Whitman , the mysterious coquette of 1788.

• How American jazz delighted the rest of the world during World War One.

• The secularization of pagoda imagery in 18thc Europe and China.

• First Lady Julia Grant and the actress Marie Dressler.

• Image: Bessie Stringfield , aka "The Motorcycle Queen of Miami", and the first Jamaican-American woman to ride solo across the US in 1930.

• A family crisis for Gen. Nathanael Greene over playing cards .

• The "Bronze-Age hunk" with the perfect smile.

• The country vicar : a popular character in fiction, the life of a real vicar was a bit different.

• Rediscovering an American community of color in pictures.

• The astonishing patchwork " graveyard quilt. "

• Image: Sterling advice from Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee.

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on February 03, 2018 14:00

February 1, 2018

Friday Video: The Countess of Provence's Fabulous Jewel Cabinet, 1787

Susan reporting,

In this era of mass-produced, particle board furniture that's bolted together and has the lifespan of a loaf of bread, it's almost impossible to imagine the level of craftsmanship, skill, and pride that went into creating something like the jewel-cabinet shown in this video. This exquisite piece was made in the 1780s by the cabinetmaker Jean-Henri Riesener for Marie-Josephine-Louise of Savoy, who married Louis XVI's younger brother, the Comte de Provence (and future Louis XVIII.)

Although the Comte and Comtesse were able to flee to the safety of the Austrian Netherlands in 1791 and therefore escape the guillotine, all their belongings were confiscated by the state. Originally the jewel-cabinet was put on public display like much of the rest of the royal furniture, but as the government's funds began to dwindle, the cabinet eventually joined the pieces that were put up for sale. (In an earlier post, I shared one of Marie-Antoinette's armchair s that ended up in the home of an American Founding Father.)

The cabinet was offered to Napoleon, who declined to purchase it, preferring to have new designs and decor to reflect his empire rather than such reminders of the ancien regine. In Britain, however, George IV, however, had no such qualms, and eventually bought the cabinet for 400 guineas in 1825. It has remained in the Royal Collection ever since: a true masterpiece.

If you received this post via email, you may be seeing a blank space or black box where the video should be. Click here to view the video.

Published on February 01, 2018 20:04

January 31, 2018

Fashions for February 1814

Ball Dress February 1814

Ball Dress February 1814

Loretta reports:

1814 puts us square in the official Regency period (1811-1819) when George III was deemed too insane to rule and the Prince of Wales became Prince Regent. Social historians tend to use the term Regency for a much broader period, from about 1800 (sometimes earlier) until 1837 when Victoria became queen.

Interestingly, the style so often associated with the Regency—the simple vertical lines ornamented with designs from Greek, Egyptian, and Etruscan art—have, by about 1814, begun to get a little fussier. By the end of the official Regency, that simple, classical look will have disappeared entirely. In 1814, though, we’re just beginning to see the change. In these two prints, it’s not as obvious as it is in some others. The walking dress especially still expresses the graceful simplicity of earlier years.

February 1814 Dress Description

February 1814 Dress Description

Walking Dress February 1814

Walking Dress February 1814

Clicking on the image will enlarge it. Clicking on the caption will take you to the source, where you can learn more and enlarge images as needed.

Published on January 31, 2018 21:30

January 29, 2018

A 19thc Maternity Robe & Corset On Display at the Museum at FIT

Susan reporting,

Susan reporting,As I've written here before, one of my favorite small museums in NYC is the Museum at FIT (Fashion Institute of Technology) . Their fashion exhibitions are drawn from their own extensive collection, and always offer a thoughtful take on the history - past and present - of clothing.

Their current exhibition is The Body: Fashion and Physique , and once again the curators challenge visitors to consider conventions and assumptions related to fashion. This time, it's how fashion distorts, contains, or reveals the human body. Examples include the exaggerated silhouette of an 1880s bustle, the balloon-shaped sleeves and full skirts to make the waist smaller by comparison in an 1830s dress, the sculptural 1950s ballgowns of Charles James, the babydoll shifts worn by a waifish Twiggy in the 1960s, or the enormous shoulder pads of the 1980s that mimicked the ideal gym-body of the time (and yes, a recording of a perky Olivia Newton commanded us to "get physical...physical!" in that gallery.) In many cases, the garment was shown side by side with the undergarments - whether stays, corsets, or girdles - required to achieve the "proper" shape.

Some of the more interesting garments addressed adjusting fashion to conform to the wearer's bodies rather than the other way around. For women in wheelchairs, designers are creating clothes that are tailored to a sitting figure, as well as shirts and jackets with special Velcro closures along the seams to make dressing easier.

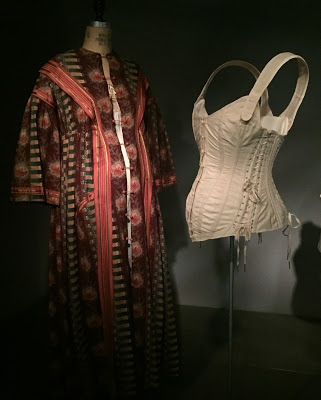

But most striking to me were these two garments, above, both 19th century maternity wear. The brightly colored robe on the left, c1860, is loose-fitting, cheerful, and comfortable, and there are plenty of modern mothers-to-be who'd wear this now. Yet as the placard noted, the robe was for a 19thc woman's "confinement": "Aptly named, confinement was a 19th-century custom dictating that expectant mothers should remain inside their homes when they could no longer conceal their pregnant bellies, which were inappropriate for public display."

There's nothing cheerful about the second garment, which is almost a visual representation of "confinement." It's a maternity corset, c1900. From the placard: "Rather than having one line of lacing up the back, [this corset] has five lines, making it adjustable at the sides. Maternity corsets were intended to help women camouflage their changing bodies, but they were also considered necessary to give support to the wearer's back and belly."

Such corsets were targeted by 19thc dress reformers, who accused the undergarments of causing miscarriages as well as undersized and deformed babies. But as fashion historian Valerie Steele (who is also the director and chief curator of the Museum at FIT) points out in her book The Corset: A Cultural History (Yale University Press, 2001), it's often difficult to separate attacks on corsets from attacks on the mother who wore them. Any imperfect child was the fault of the mother. If she'd worn a corset while pregnant, she was faulted for her vanity and selfishness, and her unwomanly lack of maternal concern - charges that were especially potent in the era of the Suffragists.

"Attacks on the corset were often linked to ideological campaigns in favor of motherhood, reflecting fears that if women broke away from their domestic sphere, the entire social order would be threatened. The German literature on dress reform is especially notable for its antifeminist bias....In France, an extremely low birthrate led to widespread fears about depopulation, but motherhood was also extolled in Britain and America."

Yet as the museum's placard noted, there were also benefits to such corsets. For 19thc women who had endured closely-spaced, multiple pregnancies and suffered from complications like a prolapsed uterus, adjustable maternity corsets like this one could actually have done more good than harm, offering support for both the abdomen and the back. Nor have maternity corsets vanished in the 21st century, either: while boning and lacing have been replaced by Spandex, modern maternity shapewear offers many of the same advantages as the old-fashioned corsets - and receives many of the same criticisms, too. Ahh, fashion!

The Body: Fashion and Physique continues at the Museum at FIT through May 5, 2018.

Maternity robe, 1860s, printed wool, USA.

Maternity corset, Ferris Bros., c1900, USA.

Both collection of the Museum at FIT. Photograph ©2018 Susan Holloway Scott.

Published on January 29, 2018 21:00

January 28, 2018

The Green Man Inn, Putney Heath

Loretta reports,

Loretta reports,The Green Man Inn at the northern end of Putney Heath features in a crucial scene of A Duke in Shining Armor . Like many of the places I use in my books, it did exist. Like not quite so many, it still exists, and so of course I was thrilled to actually pay a visit there during my stay in London last summer.

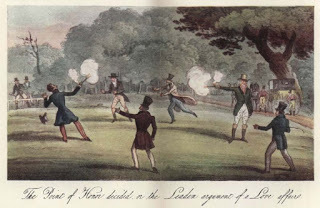

Many of the old travel books online emphasize the inn’s importance as a resort of highwaymen. However, I’ve focused on its use as a place for bolstering one’s courage before a duel and—for the survivors, a place to calm the nerves with a brandy and soda (as is recommended by my favorite book on dueling, The Art of Dueling ).

Duels took place nearby in Putney Heath at dawn or (less usually) dusk. Duelists chose out-of-the way places, like Putney Heath or Battersea Fields because they were reasonably close to London, yet far enough away to reduce chances of the authorities blundering in and spoiling the fun of men trying to kill each other. Duels, though they remained a popular way for gentlemen to settle disputes, were against the law.

Doubtless the landscape has changed over the last century and a half—fewer trees then, for instance, in many places than there are today. Still, given the heath’s reputation as a favorite spot for highwaymen, I suspected it was as easy to find a suitable place, not far from the road yet not visible from it, as it was during our visit. A short walk took us to what looked like an ideal spot: A good sized clearing where the ground was level, offering both combatants a clear sight. Yet the road wasn’t far away, and it was easy to imagine the carriages standing by, ready to take the duelists, alive, wounded, or dead, away.

Doubtless the landscape has changed over the last century and a half—fewer trees then, for instance, in many places than there are today. Still, given the heath’s reputation as a favorite spot for highwaymen, I suspected it was as easy to find a suitable place, not far from the road yet not visible from it, as it was during our visit. A short walk took us to what looked like an ideal spot: A good sized clearing where the ground was level, offering both combatants a clear sight. Yet the road wasn’t far away, and it was easy to imagine the carriages standing by, ready to take the duelists, alive, wounded, or dead, away. Images:

The Green Man photograph © 2018 Walter M. Henritze

Green Man, Putney from Charles G. Harper's The Old Inns of Old England : a picturesque account of the ancient and storied hostelries of our own country 1906

Cruikshank, The Point of Honor decided, or the Leaden argument of a Love affaire, from The English Spy , 1825

Please click on images to enlarge.

Published on January 28, 2018 21:30

January 27, 2018

Breakfast Links: Week of January 22, 2018

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.

Breakfast Links are served - our weekly round-up of fav links to other web sites, articles, blogs, and images via Twitter.• Seldom recorded by name, but definitely on board: women in the Georgian-Victorian Royal Navy.

• The intricate art of using human hair for art, jewelry, and decoration.

• Royalty, espionage, erotica: secrets of the world's tiniest photographs .

• Women had few powers in Ancient Greece - except in death.

• How did history lose Thomas Jefferson's daughter ?

• Image: Original list with alternative titles for Lord of the Flies .

• The noble art of " milling " - which to a Regency man meant a bare-knuckles fight.

• How a library handles a rare and deadly book of arsenic-laden wallpaper samples .

• " Hell's Half Acre, " the old red-light district of Los Angeles, and the nightmare of sex workers.

• The jewelry in the paintings of Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rosetti.

• The cost of comfor t: the 1761 expenses of wealthy New Yorker Philip Schuyler.

• "The Royal Women of Amarna" explores images of beauty in Ancient Egypt; download to read for free.

• Image: A patriotic (though aristocratic) 17thc wine cooler .

• How beautiful is this patent drawing for a bendy straw ?

• Dispelling Tudor myths : Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury.

• A 350-year-old recipe for "pumion" pie .

• Runaway spouses : naming and shaming.

• Tommy Thumb's Pretty Song Book, c1744, earliest surviving collection of nursery rhymes, includes a song about a bedwetter called " Piss a Bed ."

Hungry for more? Follow us on Twitter @2nerdyhistgirls for fresh updates daily.

Above: At Breakfast by Laurits Andersen Ring. Private collection

Published on January 27, 2018 14:00

January 25, 2018

Friday Video: Automaton Dulcimer Player

Loretta reports:

Loretta reports:Susan and I have shown you quite a few automatons and clockwork devices over the years. This one came to my attention via a newspaper advertisement by fabulous antique emporium M.S. Rau Antiques . If I ever get to New Orleans, that will be one of my first stops.

This dulcimer player may have inspired the more famous one belonging to Marie Antoinette, which Susan reported on a while back.

Video: Rare Automaton Dulcimer Player from M.S. Rau Antiques

Readers who receive our blog via email might see a rectangle, square, or nothing where the video ought to be. To watch the video, please click on the title to this post.

Published on January 25, 2018 21:30

January 24, 2018

More Military Camp Followers, Young & Old, 1782

Susan reporting,

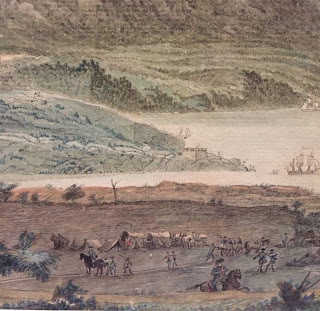

Susan reporting,Last year I wrote a post about 18thc artifacts and paintings that showed how the children of soldiers followed their parents to war. Here's another example showing both women and girls as part of a Revolutionary War encampment.

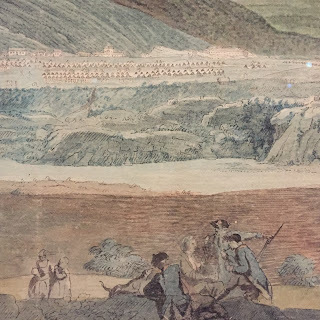

The exhibition Among His Troops - currently at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia through March 4, 2018 - is primarily focused on the Museum's new acquisition, a watercolor panorama by the French engineer Pierre L'Enfant of the Continental Army's encampment at Verplanck's Point in 1782. (More about this painting in my blog post here .) But also included in the exhibition is another, similar watercolor by L'Enfant showing the army's encampment that same year at West Point.

Owned by the Library of Congress, this watercolor, shown in its entirety below, has seldom been exhibited; for those of you unable to travel to Philadelphia, it's available to view on the LoC site here . For most of the war, West Point had served as the strategic and administrative headquarters for the Continental Army. This watercolor depicts not only the 18thc landscape of the Hudson River and the surrounding regions, but also the rows upon rows of soldiers' tents in the distance as well as West Point's buildings, fortifications, and encampment. As the exhibition's placards note, today's cadets at the United States Military Academy continue to march and train on the exact same ground the Continental soldiers were using in 1782 - and in this painting.

Details, right and lower left, in the foreground show more of everyday life in the encampment. Soldiers gather to talk and rest, muskets are neatly stacked at the ready, officers are shown on horseback, and wagons and ships on the river bring supplies and news.

But there's one small group in the foreground, upper left, of special interest. A woman is shown holding a tin kettle for three soldiers to eat directly from it, while an interested (and likely hungry!) dog waits nearby. To their left are two girls climbing up the hillside. Again according to the exhibition's notes, documents from 1782 list 150 women and children at West Point in addition to about 3,600 soldiers. Wives, daughters, and sweethearts, these women sewed, washed laundry, and supplied food for the men - important if often overlooked contributions to the military effort.

Many thanks to Phil Mead and Scott Stephenson for the early tour of the exhibition, and to Alex McKechnie for her assistance.

Panoramic View of West Point by Pierre Charles L'Enfant, watercolor, August 1782, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Published on January 24, 2018 19:00